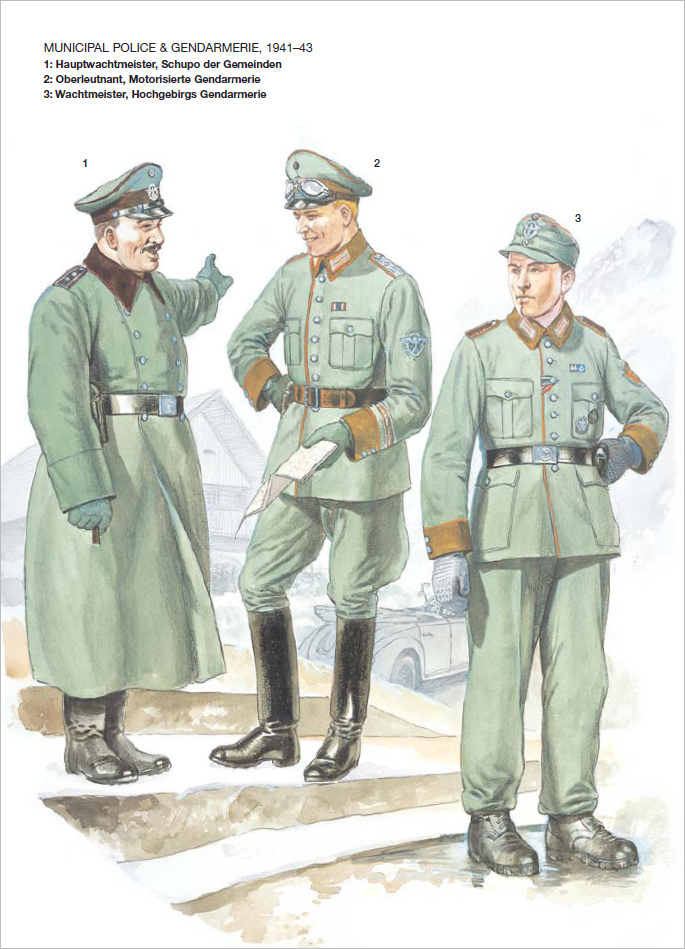

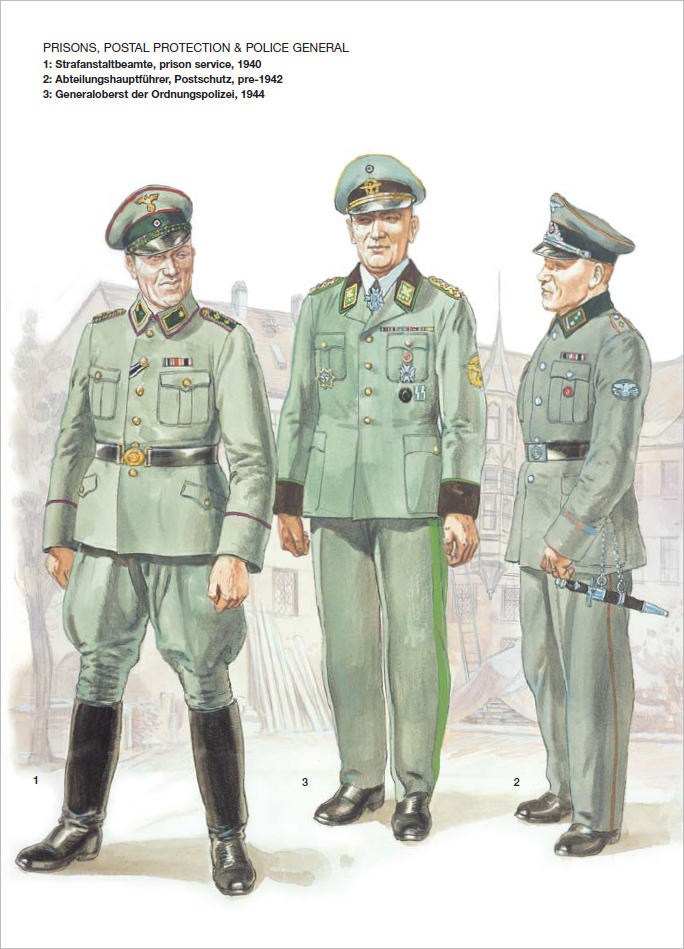

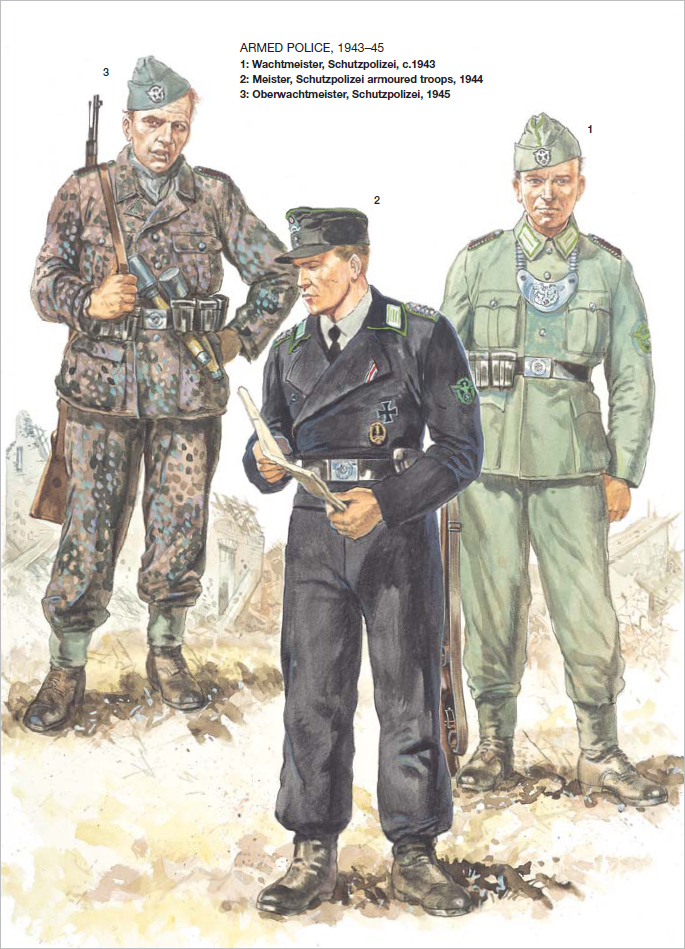

The Gendarmerie may be defined as the rural Police, maintaining law and order in countryside areas, villages or small towns. Initially these were defined as communities with fewer than 2,000 inhabitants; this was later increased to 5,000, but progress in expanding the Gendarmerie was relatively slow, and most areas with over 2,000 inhabitants remained under the control of the Schutzpolizei. The Gendarme often operated from his own home, and was not far removed in many respects from the typical British ‘village bobby’ of the day. He was expected not only to enforce the law but to advise the local community on all matters involving officialdom.

The basic unit was in fact the lone officer, known as the Gendarmerie Einzelpost – literally, ‘a post filled by an individual’. In larger villages a few policemen might operate under the control of a Wachtmeister or Oberwachtmeister from a small office. A number of such small posts came under a Gendarmerie Gruppenpost with a senior NCO in administrative control, but he would not interfere with day-to-day matters. Within a geographical district such small posts answered to a Gendarmeriekreisführer or District Police Leader, usually a Leutnant or Oberleutnant in overall charge of perhaps 40 men. In a particularly large district the Gendarmeriekreis might be subdivided into Gendarmerieabteilungen (Police Detach-ments) each with around 20 men.

The next largest unit was the Gendarmerie-hauptmannschaft, with a Hauptmann or Major in control of several Gendarmeriekreise, usually with around 140–150 men. This commander was in turn responsible to the Kommandeur der Gendarmerie for the region. That officer was based at the headquarters of the Befehlshaber der Orpo at the military district headquarters for the region. Final authority lay with the Generalinspekteur der Gendarmerie, within the Hauptampt Orpo in the Ministry of the Interior.

From 1941, in the more remote mountainous regions (generally above 1,500m/ 5,000ft) of Bavaria and Austria, the Gendarmerie were given special training as mountain guides and formed into the ‘High Mountain’ or Hochgebirgs Gendarmerie.

This branch was created by Himmler in June 1937 and tasked with the control of traffic on both motorways (Autobahnen) and first-class roads (Landstrassen) – to apprehend stolen vehicles, attend traffic accidents, and so forth. Unlike the regular Gendarmerie, the remit of the Motorized Gendarmerie covered the entire Reich; they could thus pursue a suspect vehicle across the various German ‘state lines’. They were housed in barracks and organized along military lines into platoons (Züge) and companies (Kompanien). These units, too, were under the command of the regional Kommandeur der Gendarmerie. The basic unit was the Kompanie, comprising three officers and 108 men, this being subdivided for operational purposes into Züge each of one officer and 36 men; several Kompanien could be assembled into a Gendarmerie Bataillon. After the outbreak of war the Motorized Gendarmerie were also used in the occupied territories to assist the Army’s traffic regulators, and to help maintain the security of supply routes. They carried no heavy weapons but were armed with rifles, pistols and machine pistols. On the outbreak of war numbers of former members of the Motorized Gendarmerie were drafted into the Army to help form the military police – Feldgendarmerie.

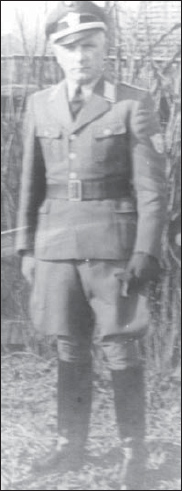

A junior ranker of the Gendarmerie in service dress. Although the lighter brown of the tunic facings is not evident here, the orange Truppenfarbe is visible in the backing to his collar Litzen, and (despite the low contrast) can just be made out in a Y-shape of piping on the front of his cap crown. (Josef Charita)

Two mountain policemen of the Hochgebirgs Gendarmerie. The normal headgear for this branch was a short-peaked cap based on the Birgmütze of the mountain troops. Both men display the full-size white metal cap insignia; and the NCO on the right wears the Army-issue padded, reversible grey/white hooded winter overjacket and trousers. (Josef Charita)

In rural areas the Gendarmerie could call upon the assistance of the Landwacht, an auxiliary force created in 1942 on the orders of SS-Ogruf Daluege. Part of the perceived need for such a force lay in the presence in rural areas of large numbers of foreign workers (who in 1944 exceeded seven million), some of them paid volunteers, but many conscripted forced labourers and prisoners-of-war who had to be guarded and supervised. The Landwacht were recruited from the SA-Wehrmannschaften – those SA members who had not been called up for military duty but had been given some basic military training. Only cadres were uniformed, as Gendarmerie with a modified Police eagle cap badge incorporating a scroll at the bottom of the wreath; but all personnel were provided with a white armband bearing the legend ‘Landwacht’ in black block letters low on the brassard. They were armed only with rifles and pistols. National command of the Landwacht was held by SS-Ogruf Friedrich Alpers.

Headgear

The Gendarmerie shako differed in that the peaks and top were in brown rather than black. Peaked caps were of standard Police pattern, but the band was of a lighter shade of brown, and the piping orange. In the field, a sidecap or peaked field cap was often worn.

Tunics

The basic grey-green uniform for home service was as described above for the Schutzpolizei, but with light rather than dark brown facings, and orange piping and underlays. The Police eagle on the left sleeve was also machine-embroidered in orange on a grey-green base, with the usual black swastika, and initially with the district name embroidered above; officers’ eagles were hand-embroidered in silver wire, and lacked the district name. The tunic was worn with either breeches and brown jackboots, or long straight-legged trousers and shoes. The Hochgebirgs Gendarmerie wore mountain trousers and short mountain boots.

Gendarmerie operating outside Germany would eventually receive a field blouse based on the M1943 Army style, in field-grey wool without collar and cuff facings. The sleeve eagle was displayed but lacked any district name. Lightweight summer tunics were also used.

Insignia

Apart from the orange branch colour, Gendarmerie insignia were identical to those used by the Schutzpolizei; but a special cuffband was produced for the motorized branch, and worn on the lower left sleeve just above the cuff. Made from mid-brown wool, it bore the silver-grey title ‘Motorisierte Gendarmerie’ in Gothic script; this was machine-embroidered for enlisted ranks and hand-embroidered in silver wire for officers, whose bands also had edging in silver ‘Russia braid’ (a piping with a central seam giving a doubled appearance). A further cuffband in the same colours and style was produced for Gendarmerie personnel working under the control of the Army outside Germany in the occupied territories; this bore the Gothic script title ‘Deutsche Wehrmacht’.

Accoutrements and sidearms

Gendarmerie wore brown leather belts and boots, otherwise identical to those for the Schutzpolizei. Gendarmerie officers and warrant officers used the same sword, and junior ranks the same bayonet as the Schupo, but with brown rather than black scabbards.

Before the end of World War I, Germany had maintained a number of overseas colonies – in South-West Africa, Cameroon, and at Kiautschau [sic], China. In 1936 the Police of three German cities were given the honour of maintaining the traditions of the former Colonial Police: Bremen (SW Africa), Kiel (Cameroon), and Hamburg (Kiautschau). A special cloth tradition badge was worn on the lower left sleeve: a white heater shield with a narrow black cross, and a red upper left canton bearing the five white stars of the ‘Southern Cross’ constellation. When German forces entered North Africa in 1941, Himmler founded the Kolonialpolizei, tasked with preparing for the employment of the Orpo in future German colonies. It is believed that a small number of Kolonialpolizei may have been employed in North Africa in 1942–43.

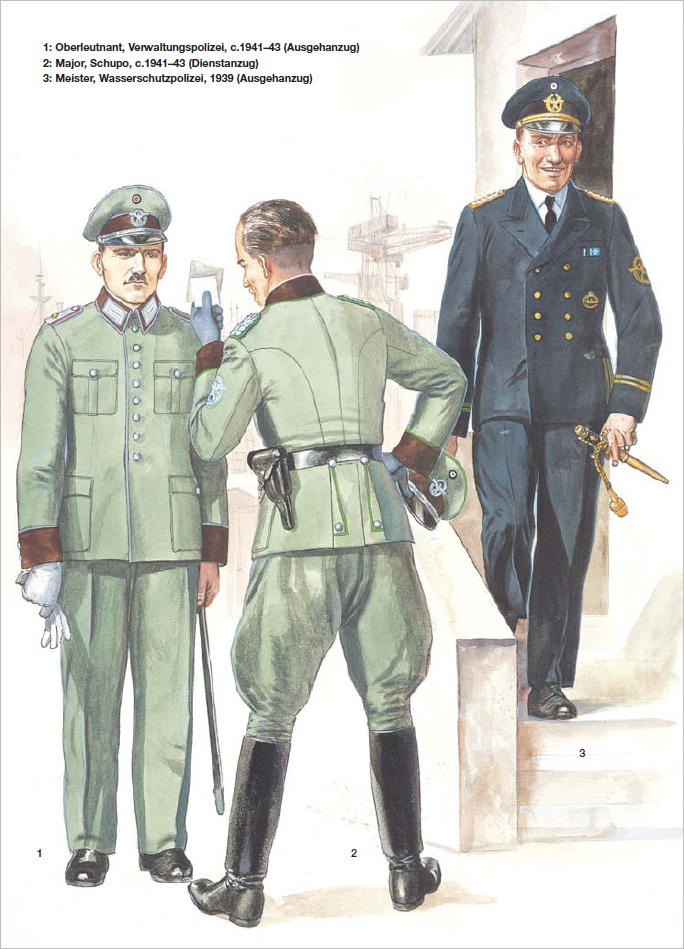

The forerunner of the Wasserschutzpolizei (WSP), the Reichswasserschutz, was tasked with the protection of life and property, and the prevention of crimes such as smuggling and unauthorized fishing, on Germany’s inland waterways. In 1936, as the Wasser-schutzpolizei, it was given its own distinctive naval-style uniform; and in 1937 the WSP officially took responsibility for all Police matters relating to maritime traffic, replacing smaller organizations such as the Schiffahrtspolizei and Hafenpolizei.

On the outbreak of war the Wasserschutzpolizei provided the manpower for the Marineküstenpolizei (MKP), which would perform similar duties in occupied territories; the first MKP units were set up in occupied Denmark in 1940, staffed by former members of the Berlin WSP. These Police personnel then came under the direct control of the Kriegsmarine, although for some time they continued to wear WSP uniforms and insignia. While the WSP covered the inland waterways, the MKP was responsible for securing coastlines and large harbours, and maintaining discipline in naval ports. The WSP also maintained offices or Dienststelle in those occupied areas with inland waterways; one was established in Rotterdam, and others in Poland, Russia, Finland and Serbia.

The organization of the WSP seems to have been extremely flexible. Basic patrols (Wachen) could consist of one or two policemen on foot or bicycle, to patrol the paths bordering canals and riverbanks. In areas of heavier traffic they could use small motor boats, and in some cases might use larger launches to patrol areas of coastline. WSP squads operated from local stations (Stationen), in turn responsible to precincts (Revier Zweigstellen). The area, district or precinct command was the Revier, under an Oberleutnant or Hauptmann, answerable in turn to a sector (Abschnitt) command, typically under a Major. A group of such sector commands was controlled by a Kommando, usually headed by an Oberstleutnant or Oberst.

An NCO of the Wasserschutz-polizei wearing that organization’s dark blue naval-style uniform – see Plate C3. The peaked Schirmmütze is the earlier style with a wire-stiffened crown; it bears a gilt national emblem, and for this rank a black chin strap. Note the single yellow braid cuff ring and yellow sleeve eagle. (Josef Charita)

An Obermeister of the Wasserschutzpolizei, whose senior warrant officer rank entitles him to officer-style gilt cords on his later, unstiffened naval cap. (Josef Charita)

Like the land services, the Wasserschutzpolizei could call for assistance from auxiliaries; the NSKK operated its own marine section, the NSKK-Motorbooteinheiten. In some large ports the Allgemeine-SS also provided harbour security units (SS-Hafensicherungstruppen) to assist the Police.

A naval-style peaked cap was worn by WSP personnel, in midnight-blue with a black band, and without piping. The peak (visor) was black; a black leather chin strap was worn by junior ranks and gilt chin cords by officers and warrant officers. The usual national cockade was displayed on the front of the crown, and a gilt metal Police eagle on the band. A sidecap might also be worn; similar to the midnight-blue boarding cap of the Kriegsmarine, it bore a machine-woven Police eagle in yellow on black on the front of the flap, below a national cockade on the crown.

A midnight-blue double-breasted ‘reefer’ jacket was worn with matching straight trousers (dark blue breeches and high boots were less commonly used), a white shirt and black tie. The jacket had two rows of four gilt buttons. The Police sleeve eagle was in bright yellow embroidery (gold for officers) on dark blue. Shoulder straps of Polizei pattern had, for enlisted ranks, bright yellow central cords and silver outer cords flecked with yellow chevrons, all on a bright yellow underlay Senior NCOs and warrant officers wore single and double rings of bright yellow braid around both sleeves at cuff level.

The uniform worn by the MKP were eventually replaced with Kriegsmarine issue items, for a transitional period with full Polizei insignia; rank insignia were later replaced with regular Kriegsmarine patterns. There was a narrow midnight-blue left cuffband with yellow edges and ‘Marine-Küstenpolizei in Gothic script. Belts were not worn over the reefer jacket in service dress; in other uniform orders, the buckles of the black leather belts were identical to the Schupo patterns but in gilt rather than silver finish.

Wasserschutzpolizei officers and warrant officers were also authorized their own dress dagger for a limited period; introduced in 1938, it was based on that of the Kriegsmarine. However, the white grip of the naval dagger was replaced with dark blue leather with gilt wire wrap, and fitted with a gilt metal Police emblem. In place of the eagle-and-swastika naval pommel it featured a flaming ball pommel. The dagger was withdrawn in April 1939, after which date it was to be replaced with the regular Police sword.

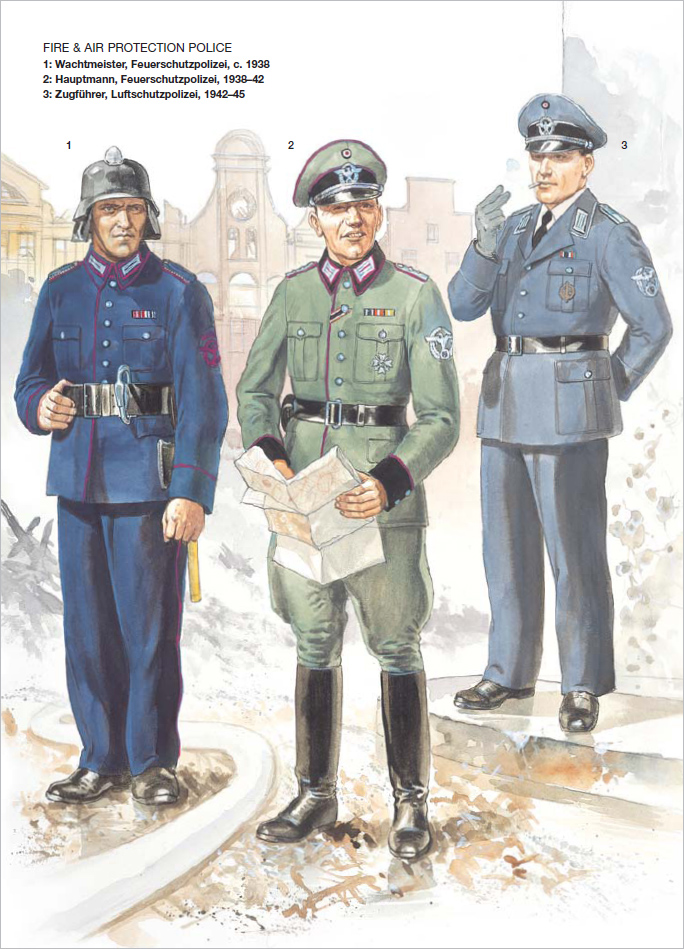

Before the advent of the Nazi regime, Germany had a two-tier fire brigade system: larger towns and cities had full-time fire-fighters, and rural areas part-time volunteers. In January 1934 the Nazis subordinated all fire-fighting services to the control of the Ord-nungspolizei. Interestingly, after the campaign against Poland, Police officials interviewed Polish fire brigade personnel to ascertain how they had dealt with the Luftwaffe’s bombing campaign. The result was a decision in late 1939 to form a number of Feuerschutzpolizei regiments. All full-time fire-fighting services in the larger towns were to be transferred to the Feuer-schutzpolizei, while the rural part-time volunteer brigades – Feuerwehren – were to be retained. The regiments formed were as follows:

Feuerschutzpolizei Regiment 1 Based in Saxony, elements of the regiment also served in the occupied Netherlands and France, especially around the ports of Le Havre, Lorient, Brest and St Nazaire. A detachment also served on the Eastern Front, where they helped provide protection to the Ploesti oilfields in Romania.

Feuerschutzpolizei Regiment 2 Based in Hanover.

Feuerschutzpolizei Regiment 3 Based in East Prussia, and also served in occupied Poland.

Feuerschutzpolizei Regiment 4 Based in the occupied Ukraine.

Feuerschutzpolizei Regiment 5 Based in occupied Czechoslovakia.

Feuerschutzpolizei Regiment 6 Based in the occupied Netherlands.

At a lower level, as one might expect, the Feuerschutzpolizei were at the disposal of the local civil authorities under the Bürgermeister, who would act in co-ordination with the Polizeipräsident. The costs of operating the Feuerschutzpolizei were borne by the local community they served. Locally, the Feuerschutzpolizei were controlled by the Kommandeur der Feuerschutzpolizei, who would oversee a number of Abschnittskommandos or sector commands, which in turn were subdivided into detachments or Feuerwachen. The smallest single unit was the platoon or Feuerlöschzug, usually comprising two or three fire engines and ten to 12 firemen. Each Feuerwache would comprise several such Feuerloschzüge, the number being determined by the size of town, the fire risk level (e.g. the number of factories, etc), but one Feuerwache would cover the same area as several police precincts.

The ‘police’ aspect of the Feuerschutzpolizei is explained by the fact that when necessary they could be called upon to take on the tasks of the Gendarmerie or Schutzpolizei if these were unavailable, and that they had full police powers. Thus a member of the Feuerschutzpolizei could, for example, arrest any suspects found at the scene of a suspicious fire. In the early stages of the campaign in the West, Feuerschutzpolizei units followed the armed forces into enemy territory to help save any installations fired by the retreating Allies.

A group of NCOs of the pre-1938 Feuerlöschpolizei illustrate the inconsistency seen during the interim period when both old-and new-style uniforms were being worn. Most wear the old dark blue uniform with carmine distinctions, with the addition of Police cap badges and sleeve eagles. Only the man sitting in the centre of the front row seems to have the full set of new-style insignia. (Josef Charita)

An NCO of the Feuerschutz-polizei gives instruction to a group of Hitler Youth auxiliaries – note their broad fire-fighting belts with a karabiner spring hook for a running rope. The instructor displays a district name above the Police national emblem on his left sleeve; he also gives a good side view of the thin, black-painted helmet with its sharply angled break between the front peak and side brim. It is fitted with Y-shaped chin straps for greater security. (Josef Charita)

At the height of the Allied bombing offensive it has been estimated that as many as 2 million people served in the Feuerschutzpolizei and Freiwilligen Feuerwehr. As the war dragged on the need for front-line troops saw the ranks of the Feuerschutzpolizei being filled by increasing numbers of eastern ‘volunteers’ from Poland and the Ukraine. As the Third Reich crumbled a number of Feuerschutzpolizei found themselves in combat situations, thrown into desperate attempts to defend their cities against the enemy.

Generalmajor Walter Goldbach, commander of the Berlin Feuerschutzpolizei, realizing that Germany’s final defeat was imminent, had accumulated stocks of fuel; and on 22 April 1945, just before Berlin was finally cut off, he sent his units westwards to safety in Schleswig Holstein, where they surrendered to the British. Four days later Goldbach paid for his devotion to his men; he was shot by the Schupo during his arrest for treason and, though critically injured, he was dragged from his hospital bed and executed just days before the war ended.

Headgear

A peaked cap was issued, in dark blue with a black band, piped in carmine at the crown seam and both edges of the band, and bearing conventional Police insignia. On fire-fighting duty a steel helmet was worn. This generally resembled the Wehrmacht pattern, but was of thinner metal, with two circles of ventilation holes in each side. It had sharply squared-off corners to the brim above the ears in place of the M935 Wehrmacht helmet’s smooth curve; and it was made both with (for parade) and without a bright aluminium comb to the top of the skull, contrasting with the black paint finish. Regular Police decals were applied to the sides. It could be fitted with a protective leather neckflap under the side and rear brim.

Tunics

The Feuerschutzpolizei initially wore a dark blue, single-breasted, four-pocket tunic, with eight aluminium front buttons, and carmine piping to the collar, cuff tops, front edge and rear skirt panels. It bore Police-pattern collar patches and shoulder straps worked on carmine underlay. Matching trousers had carmine piping to the outseams.

In 1938 regular grey-green Police uniforms were authorized. These initially featured black collar and cuff facings, and the distinctive carmine piping of this branch; but from 1942 the black facings were changed to Police dark brown. The peaked cap changed to grey-green with a black, later dark brown band with carmine piping. The left sleeves of both tunics displayed the Police national eagle emblem in carmine thread, with the district name embroidered above in an arc shape; officers wore silver eagles without the district names.

Accoutrements

The conventional black leather belts with Police buckles were worn by the appropriate ranks with service dress; but a distinctive fire-fighting belt was also worn. This was very broad, with a deep two-claw frame buckle and a wide leather keep; mounted on the left front was a large, bright steel ‘karabiner’ or spring hook, into which a running rope could be pressed with one hand. A hatchet was worn from this belt on the left hip, haft down, with the head enclosed in a black leather case hanging on a strap.

From 1936, officers and warrant officers were authorized to wear the regular Police sword. Junior ranks were authorized a dress bayonet based on the standard military pattern, but lacking a fixing slot and with an S-shaped quillon. The metal fittings were nickel-plated, and the grip in chequered black Bakelite. Blade length was 35cm (13.75in) for NCOs and 40cm (15.75in) for junior enlisted ranks; saw-backed blades could also be provided at extra cost – all of these dress sidearms were privately purchased rather than official issue.

Although this branch should really be considered an auxiliary force, it is dealt with here for the sake of simplicity. As already noted, the Feuerwehr consisted of those part-time volunteer firemen who served rural communities, but also included some other, smaller organizations:

Freiwillige Feuerwehr The local part-time volunteer fire brigades in rural communities; after the creation of the Feuerschutzpolizei, these were officially classed as Technische Hilfspolizei (Technical Auxiliary Police). Each village or district was obliged by law to create such a fire service. Although civilian volunteers, the members came under the direct control of the Ordnungspolizei.

Pflichtfeuerwehr With wartime demands on manpower, there were often occasions when there were insufficient volunteers to create a fire brigade. In such cases the authorities were entitled to draft suitable individuals for compulsory service. All German males between 17 and 65 were liable for call-up to serve in the Feuerwehr.

Werkfeuerwehren These were organized by the management of individual factories and manned by employees of the firm. The decision as to whether a Werkfeuerwehr was to be created was a matter for higher authorities. Minimum manpower requirement for a Werkfeuerwehr was 18 men and one power-driven pump unit.

HJ-Feuerwehrscharen The Hitler Jugend also contributed volunteer auxiliary firemen. Each HJ-Feuerwehrschar consisted of around 45 to 50 youths divided into three fire-fighting squads or Kameradschaften, trained and equipped by the local Feuerwehr and at the disposal of the local fire chief.

The costs of all of these Feuerwehren were met by the local community. Feuerwehren within an area were under the control of a Bezirksführer appointed by the local Police President. His area of command would then be divided into several Kreise or districts each under a Kreisführer; subordinate to the Kreisführer might be several Unterkreisführer, with each individual Feuerwehr unit commanded by a Wehrführer. In the case of Pflichtfeuerwehren, such units came under the control of the nearest Feuerschutzpolizei commander.

The Feuerwehr wore the same dark blue uniform as the Feuer-schutzpolizei, but with their own collar patch and shoulder strap insignia.

Female auxiliaries serving with the Feuerschutzpolizei being fitted with the black-painted FSP steel helmet, complete with its leather neck flap; this photo clearly shows the silver-grey-on-black Police decal on the left side and the red, white and black Party decal on the right. The women wear thick protective clothing with fly fronts and open patch pockets, in an unidentified shade probably of either grey or blue; on the left sleeve a district name and Police national emblem are sharply visible, apparently in white on a dark patch. (Josef Charita)

The responsibility for air raid precautions (hereafter in this text, ARP) and assistance initially lay with the pre-war Reichsluftschutzbund (RLB), a semi-official Party-sponsored organization. This was later taken over by the Air Ministry, and in each Luftgau or ‘air district’ of Germany an RLB Gruppenführer was appointed to control ARP matters in that area. The RLB were designated as auxiliary policemen when carrying out their duties; a large proportion of the members were part-time volunteers.

Working with the RLB were the RLB Warndienst (Air Raid Warning Service – see below); and the Sicherheits und Hilfsdienst (SHD), which was a mobile Civil Defence force of fire-fighters, decontamination squads, repair, demolition, medical and veterinary units. SHD men were conscripts who were employed full time and stationed in barracks, but were allowed to sleep out in rotation, and were exempt from military conscription while serving. Mobile SHD units were allocated to just over 100 cities in Germany – those considered most likely to suffer air attacks.

With the onset of the major Allied bombing campaign against Germany it quickly became clear that the existing ARP structures were unable to cope; and in March 1942, Himmler instituted a new organization, the Luftschutzpolizei, under his own direct command. Personnel of the former motorized units of the SHD were absorbed into the Luftwaffe as Luftschutz Abteilungen, continuing to carry out principally fire-fighting, demolition and rescue duties but under the control of the Luftwaffe rather than the Polizei. All other SHD personnel were absorbed into the new Luftschutzpolizei. The Luftschutzpolizei included both full-time regular personnel and part-time auxiliaries; the full-time elements comprised the following specialist units:

Feuer- und Entgiftungsdienst Regular fire-fighting and decontamination units, which were trained by the Feuer-schutzpolizei.

Instandsetzungsdienst

Responsible for emergency demolition of unsafe buildings and repairs to those that could be saved.

Fachtruppe Technical specialists to deal with damaged gas mains, water mains, power cables, sewers, etc.

Luftschutzsanitätsdienst First aid branch.

Luftschutzveterinärdienst Veterinary branch.

Two members of the Feuerschutzpolizei, wearing the grey-green uniform of the 1938 regulation, pose with a fire brigade officer in the old blue uniform, and a unit from one of the volunteer Feuerwehren in the provinces. These part-time fire-fighters have been issued military M1935 helmets, and two-piece protective clothing with exposed buttons and two patch pockets with pointed flaps. Apart from helmet decals no insignia are visible; but note the broad belts with spring hooks, and the cased hatchets hanging low on the left hip. (Josef Charita)

As an auxiliary force, the Luftschutzpolizei were subordinate to the Ordnungspolizei; they took their instructions from the regular Police, and personnel did not have powers of arrest. As wartime pressure on manpower increased, women were also recruited into the Luftschutzpolizei to release men for military service.

The former SHD kept their original Luftwaffe-style uniforms, initially with their own distinctive insignia, including dark green collar patches of Luftwaffe shape bearing the letters ‘SHD’ in silver-grey Gothic script; enlisted ranks’ patches had green-and-white twist edging, officers’ patches plain silver cord; officers also wore Luftwaffe-style silver cord piping around the top half of the open tunic collar. Shoulder straps were narrow; for enlisted ranks they were of dark emerald-green, with for NCOs a narrow silver cord inset from the edges, and aluminium pips where appropriate; for officers they were of silver cord on green underlay, with a single green cord inset from the edges for junior ranks, and gilt pips.

A special silver RLB badge was worn on the cap crown, above a national cockade on the band; and embroidered, in silver thread on the right breast for officers, and in white on the upper left sleeve for enlisted ranks. This was two spread wings in roughly the style of the Luftwaffe national emblem, with a central wreath and ‘Luftschutz’ scroll above a swastika.

The different types of unit were identified by oval cloth patches bearing Gothic script characters, worn on the lower left sleeve:

F (= Feuerlösch- und Entgiftungsdienst) – white, on red patch with green edging; I (= Instandsetzung) – white, on brown patch with green edging; G (=Gasspüren- und Entgiften Ausgebildete) – black, on yellow patch with green edging, worn by Fachtruppe trained in gas detection; caduceus symbol (= Sänitätsdienst) – white, on pale blue patch with green edging; V (=Veterinärdienst) – white, on violet patch with green edging. In addition, from December 1941 a green armband was worn on the upper left sleeve, bearing the legend ‘Sicherheits-u. /hilfsdienst’ in two lines of yellow Gothic script. This armband also served to indicate the wearer’s grade in the organization by means of narrow and wide braid edgings of various types.

The rank titles in the SHD went from SHD-Mann to SHD-Stabsgruppenführer, equivalent to military ranks from Schutze to Stabsfeldwebel; and from SHD-Zugführer to SHD-Abteilungsführer, equivalent to ranks from Leutnant to Oberstleutnant. Police ranks were adopted when the SHD was absorbed into the Luftschutzpolizei, but this was a gradual process.

After their transfer into the Luftschutzpolizei it was intended that these personnel would eventually receive the regular Police grey-green uniform; this change seems never to have been fully implemented, but photos show a gradual change to Police cap, sleeve and collar insignia on the Luftwaffe-style blue-grey uniforms.

From the days of the original RLB a special steel helmet was worn: resembling the military M1935 but with a broader appearance, it was of thin steel, with a raised rib all round the base of the skull and ventilation holes each side. A decal of the Luftschutz winged badge was worn on the front. This helmet remained in use by the Air Protection services throughout the war.

A blurred but rare photograph of an officer of the Luftschutz-polizei, wearing the Luftwaffe-style service cap and uniform with Police badges as introduced for the new service after March 1942, when it was created from part of the former Sicherheits und Hilfsdienst – see Plate E3. The collar patches are of Police type, and are on black underlay, as are the narrow silver shoulder cords. (Josef Charita)

Another group of female auxiliaries receive helmets, this time the broad Reichsluftschutz-bund pattern with a raised rib around the base of the skull. These helmets were painted Luftwaffe dark blue-grey, and bore the Luftschutz decal on the front in silver-grey. Yet another type of protective one-piece coveralls can be seen here, apparently in a waterproofed cloth. (Robert Noss)

In all the ‘hands-on’ emergency services, both full- and part-time, personnel were issued for hard physical labour a variety of off-white (undyed) cotton drill jackets and trousers, or baggy overalls in various shades of grey, blue and brown.

* * *

As the Luftschutzpolizei was subordinate to the Orpo, so other, lesser organizations were subordinated to it:

Werkluftschutzdienst Factory air raid services, recruited from factory staff and supervised by local management.

Werkschutzpolizei Also recruited from factory staff, their primary task was prevention of theft or sabotage, but they were often called upon to work alongside the Werkluftschutzdienst. Werkschutz personnel were usually issued military-style uniforms of either dark blue or dull grey, which might have either open or closed collars, and a military-style peaked cap. Insignia varied widely, but usually included the Werkschutz cap and sleeve badges; cuffbands were issued in various colours, with the legend ‘Werkschutz’ in block letters. The left sleeve badge was embroidered in silver-grey on a black or grey oval edged with silver-grey cord; it showed a stylized factory over half a cogwheel, between wings, all ‘protected’ at the left by a tilted shield emblazoned with a black swastika. The aluminium cap badge was a distinctively shaped eagle with the same shield. In some cases a company logo might be worn in the form of collar patches.

It would appear that control of these personnel remained under Göring’s Air Ministry and was not transferred to the Ordnungspolizei, as were most other such smaller organizations.

Selbstschutz These were the purely civilian volunteers who acted as fire-watchers, wardens at apartment blocks, etc, and were broadly equivalent to the ARP volunteers found in Britain. Similar volunteers worked in the commercial (as opposed to industrial) sectors, providing wardens for department stores, hotels, theatres and other buildings.

Luftschutzwarndienst Broadly similar to Britain’s Observer Corps, their job was to provide early warning of approaching enemy aircraft. They were absorbed by the Luftwaffe in 1942, but civilian auxiliaries, both male and female, still worked alongside their Luftwaffe and Police colleagues.4 Luftwaffe-style uniforms were worn, initially with the same shoulder straps and collar patches as the SHD, but with the letters ‘LSW’ on the dark green patches.

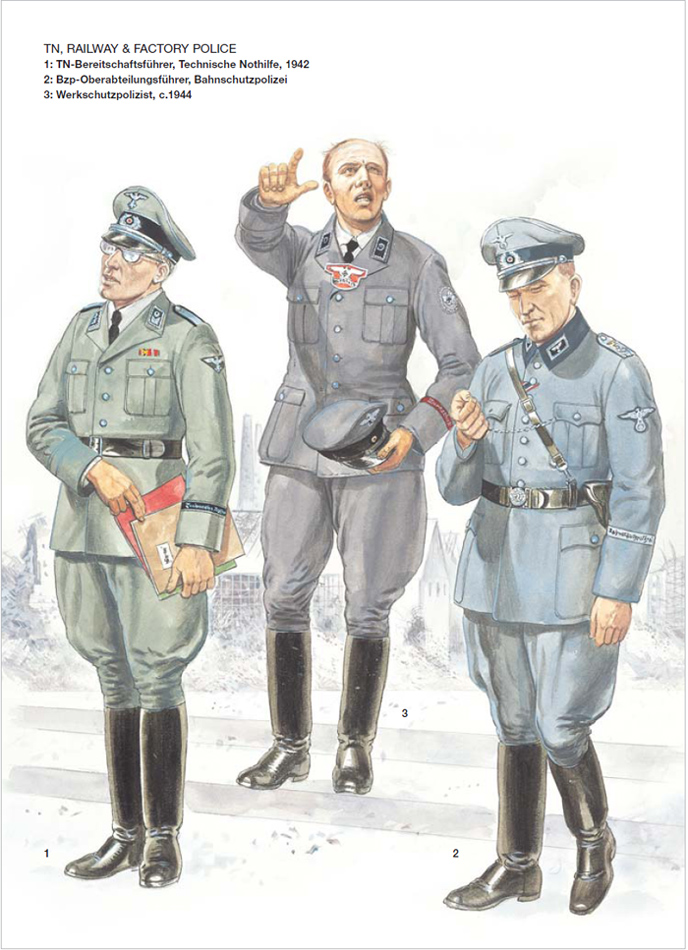

The Technical Emergency Service (TeNo or TN) was composed of technical specialists in a wide range of disciplines which were essential in responding to emergency situations in both peace and war: construction, demolition, maintaining and repairing the means of power and water supply, land and waterway communications, and so forth. It had been founded in September 1919, when it effectively acted as a strike-breaking force during the political unrest of the first years of the Weimar Republic, to ensure that essential services were maintained. In 1937 it became an auxiliary branch of the Order Police. In 1939 its members were given the right to bear arms.

During wartime, TeNo members were generally above the age for military service (between 45 and 70 years). Although membership was voluntary – at least initially – once accepted a member could not simply leave at will. The basic TeNo unit was the Kompanie, which comprised several specialist sections. Five such companies could be assembled to form a TeNo Abteilung, covering a geographical area; it is believed that about 13 such areas had their own TeNo Abteilungen. In addition, TeNo units operated alongside the Wehrmacht, providing specialist advice and assistance in the occupied territories. Such units were controlled by a TeNo-Einsatzkommando located with the senior Army headquarters in the region.

Prior to the outbreak of war TeNo personnel wore a midnight-blue uniform consisting of an Army-style field cap (sidecap) or peaked service cap; a four-pocket, open-collar tunic with four aluminium front buttons; a white shirt and black tie; midnight-blue trousers, jackboots or shoes. A matching double-breasted greatcoat had two rows of aluminium front buttons, and displayed collar, shoulder and sleeve insignia.

Insignia were in white or silver (depending on rank) on black. The distinctive piping around enlisted ranks’ shoulder straps and collar patches was white with a light black fleck. Officers seem to have worn black-flecked silver edging on collar patches, plain silver piping on caps, and plain black underlay on shoulder straps. Four main ‘services’ or branches were distinguished by coloured piping on officers’ collars of the blue uniform, and the fist straps of dress sidearms: blue (Technical Service, TD); red (Air Protection Service, LD); orange-yellow (Emergency Service, BD); and green (General Service, AD).

From 1940 those personnel attached to the armed forces were issued a plain field-grey Army-style uniform, with a black band and silver piping on the officer’s peaked cap; this uniform became increasingly common during the war. From October 1942 a change to Police uniform was ordered, with black facings and sleeve eagle, but this seems to have been only partly achieved.

The service had its own complex rank title sequence, which was revised in 1941 and again in 1943, some rank insignia being changed accordingly; the picture is further confused by the fact that blocks of several ranks wore the same insignia. In 1937–41 black rectangular collar patches with cord twist edging showed the rank on the left patch, and for all ranks below TN-Landesführer the wearer’s unit and detachment, by a combination of Roman above Arabic numerals, on the right. Ranks were identified by a combination of cogwheel and laurel leaf emblems; the three most senior ranks displayed the rank on both patches. Photos dating from 1941–43 show all officer grades with mirror-image rank patches. During 1943 collar patches changed to SS pattern, with rank worn on both collars; TeNo shoulder straps are believed to have been retained.

The RLB national emblem, here in woven form for the uniform, but also used as a decal on the Luftschutz helmet worn by personnel of the SHD and Luftschutzpolizei.

The national emblem worn by the Technische Nothilfe as a left sleeve eagle. Machine-embroidered in white or silver on black, it shows the TeNo cogwheel, hammer and ‘N’ superimposed on the large swastika.

Junior enlisted ranks’ shoulder straps were black, pointed, edged with black-flecked white, and differenced by transverse white or silver-grey bars; NCO-equivalent ranks wore narrow, officer-style straps on black underlay, of silver cord with a single black cord inset from the long edges, and differenced by gilt bars; and officer-equivalents wore similar straps with plain silver cords differenced by gilt cogwheel-and-star pips. Representative examples, 1937–41, are:

TN-Vormann (equivalent to senior private): right hand patch, embroidered ‘VII/2’; left hand patch, pressed aluminium cogwheel centred; broad pointed shoulder straps, three narrow silver-grey bars across outer end.

TN-Gefolgschaftsführer (equivalent to Hauptmann): right hand patch, silver embroidered ‘II’; left hand patch, cogwheel above embroidered symmetrical double spray of laurels; narrow rounded shoulder straps, silver cord on black underlay, two gilt pips.

A national emblem of special TeNo pattern was worn on the upper left sleeve of the blue and field-grey uniforms (see photograph). White-on-black trade badges were also seen, in the form of letters or symbols surrounded by the TeNo cogwheel.

A cuffband, bearing the legend ‘Technisches Nothilfe’ in silver or silver-grey Gothic script on black, between matching edgings, was sometimes worn on the left forearm of the field-grey Army-style uniform. As well as or in place of this, personnel serving with the armed forces wore a yellow brassard on the upper left arm, with the black Gothic legend ‘Deutsches Wehrmacht’.

On the crown of the officer’s peaked cap an aluminium badge showed the TeNo national emblem, in this case with the swastika set on a diamond-shaped extension rather than the usual round Wehrmacht wreath. On the band the national cockade was centred in an Army-style embroidered silver wreath, and the usual silver cap cords were worn. A small machine-woven version of the TeNo national emblem was worn on the front of the blue and field-grey sidecaps, in silver-grey on black, above a plain cockade.

In reality, the uniform most often worn when working was a simple undyed herringbone drill fatigue suit, often devoid of insignia. Sidearms

Junior ranks of the TeNo were issued with a dress ‘hewer’. This had a heavy scimitar-style blade, a crossguard bearing the TeNo national emblem, a white grip, and a pommel vaguely in the shape of a stylized eagle’s head with a cogwheel as the ‘eye’. The metal scabbard was painted black with silvered throat and chape fittings. TeNo officers wore instead a dagger proportioned similarly to those worn by the Army, with a white spirally grooved grip, a crossguard with the TeNo national emblem, and a pommel bearing a large cogwheel.