CHESS may have been relatively new to Lewis in the late twelfth century. The origins of the game probably lie in India in, or prior to, the sixth century AD. From there it spread westwards and was widely known in Europe by the eleventh century. The earliest European chessmen copy Islamic models, being non-figurative or abstract. The Lewis chessmen are among the earliest that are shaped as recognisable figures. They are also among the earliest chessmen from the area that is now Scotland.

21. JARLSHOF GAMING-BOARD Fragment of a double-sided slate game-board (X.HSA 801 and 778) from the Viking age settlement at Jarlshof, Shetland. One side appears to have been for playing hnefatafl.

The game of chess has also evolved considerably over the centuries. Earlier versions had ministers or vizirs instead of queens, war elephants instead of bishops, and chariots instead of rooks. The composition of the Lewis chess sets – with a king and queen, bishops, knights, warders and pawns – is clearly much more relevant to the make-up of Scandinavian society in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The pawns represent the common folk, or at least those men who were obliged to do military service. The warders – the term for these pieces coined in 1832 by Frederic Madden, Assistant Keeper of Manuscripts in the British Museum – represented a more élite group of warriors, but ones not of the same high status as knights or nobles. These were (royal) retainers or mercenaries.

Chess was not the only board game that required kings and pawns. There was another game called hnefatafl, in which one player had a group of attackers arranged around the edge of the board and attempted to capture a centrally-placed king defended by his guards. The player with the king could win if he could get his king to one of the four corner squares.

Hnefatafl was already popular in the Scandinavian world prior to the advent of chess, and, as time went on, more and more turned to playing chess and hnefatafl became a minority interest or disappeared altogether. There is evidence of hnefatafl having been played in Orkney in the Viking age, in the form of game-boards, and there is one from the Viking settlement at Jarlshof in Shetland [Fig. 21]. It is crudely carved on a piece of slate. Both sides are chequered, one side with the central area in a circle and five of its squares marked with a cross. This would have been for positioning the king and four men to guard him. A hnefatafl board, incised in stone, from a thirteenth-century context at Whithorn Priory (Dumfries and Galloway) in Scotland, provides evidence that the game continued to be played at that time.

The 14 plain ivory disks [Fig. 4.61] found with the Lewis chessmen are often forgotten about, but they are important evidence that the hoard was notjust for playing chess. These disks are best interpreted as tables-men. Many other medieval tables men are known from Europe, mostly decorated and of smaller size. There is an eleventh-century bone and antler set with a board from Gloucester Castle in England, and others of eleventh to twelfth-century date from St Margaret’s Inch (Angus) [Fig. 22] and St Andrews (Fife), both in Scotland.

These tables-men were for playing a board game – tables – a forerunner of modern backgammon. Tables already had a long history, extending back for hundreds of years, by the time the pieces in the Lewis hoard were carved. Board games were widely played in the ancient world and there is evidence for them in Scotland from the Iron Age onwards.

It is possible that the Lewis hoard represents the remains of a games compendium designed for playing chess, hnefatafl and tables. What we regard as chess kings could have doubled for use in hnefatafl, along with either some pawns or warders. Indeed, it is an intriguing possibility that the craftsmen who made these pieces may deliberately have chosen warders to substitute the chariots prevalent in earlier sets precisely because they could more conveniently double for the pawns or guards of hnefatafl. Early game-boards that are two-sided – one for hnefatafl, the other for another game like tables or merels – are reasonably common in the Scandinavian world. Double-sided game boards have been with us ever since and there would no doubt have been many in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries that combined chess and hnefatafl, like apparently the board from Greenland, made of walrus ivory or whales’ teeth, given as a present to Harald Hardrada, an eleventh-century King of Norway. The source for this is the Icelandic Króka-Refs Saga, an early fourteenth-century story of doubtful historicity. There are no clues as to whether or not the Lewis hoard was buried with one or more board. If, as would have been likely, such boards were of wood, they would not have survived in the ground for hundreds of years.

22. TABLES-MAN A tables-man of 11th to 12th-century date from St Margaret’s Inch, a crannog in the Loch of Forfar, Angus.

The playing of board games was popular in both medieval Scandinavian and Gaelic society. Kali Kolsson, prior to becoming Earl of Orkney in 1129 and changing his name to Rognvald, made a poem listing the nine key skills or attributes of a nobleman. The one that headed his list was ability at playing ‘tafl’, which may have been understood to include a variety of games like chess and hnefatafl. This idea that playing games well was a mark of a great man crops up in Gaelic poetry as late as the eighteenth century. And women clearly played as well from early days. That the game was not just the preserve of nobles is demonstrated by the legend of Tristan, in a version recorded as early as 1200. It has Tristan taking ship with Norwegian merchants who have a chess-board on which Tristan plays.

The continuing interest in playing board games in the Western Isles can be demonstrated by the discovery of other tables-men dating to medieval times. From Iona Abbey there is a fifteenth-century bone piece carved with a crowned mermaid grasping her tail with one hand, and holding a fish with the other [Fig. 23]. Another bone tablesman found in a cave on the Isle of Rúm is decorated all over with an interlace design [Fig. 24]. Two decorated bone tables-men, as well as about 50 plain counters or tables-men of stone, have been recovered from the excavations at Finlaggan, the home of the MacDonalds on Islay.

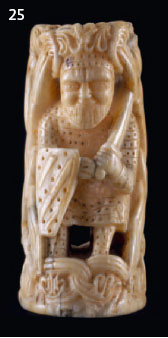

In 1782 Lord MacDonald gave the museum of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland the handle of an ancient dirk. It was only later that it was realised that this was in fact a very fine chessman (rook?) of walrus ivory, dating to the mid-thirteenth century, with two warriors, back to back in a framework of foliage scrollwork. Both are clad in mail hauberks and have drawn swords and shields [Fig. 25]. Its place of manufacture is unknown – possibly in Scandinavia or Britain. And it may have been recovered from Loch St Columba in Skye, which contained an island residence of the Kings of the Isles.

Not from the Isles themselves, but from the castle of Dunstaffnage on the west coast of Argyll near Oban, is a chess king made from a sperm whale’s tooth [Fig. 26]. The present whereabouts of this piece are unknown, but on the basis of an early nineteenth-century drawing, it can on stylistic grounds be dated to the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century. It is, however, very much still in the same tradition as the Lewis chessmen.

23 AND 24. TABLES-MEN Bone tables-man (23) (NMS H.NS 99) from the Isle of Rum, c.1500, and (24) (NMS H.NS 92) of 15th-century date from Iona abbey.

25. CHESS KNIGHT Made of walrus ivory, mid-13th century, possibly from Isle of Skye (NMS, H.NS 15).

26. CHESS KING Made from the tooth of a sperm whale in the late 15th or early 16th century, this piece was discovered at Dunstaffnage Castle near Oban, Argyll. From an early 19th-century drawing.

All this reinforces our contention that the presence of the Lewis chessmen on Lewis should not be seen as some aberration, resulting from their loss in transit elsewhere.

Their loss must be viewed as accidental, but not unreasonably a matter involving an owner who lived on or frequented Lewis, failing to recover this treasure which he had temporarily hidden for safekeeping.