Turkey’s position where West meets East made it the world’s connective tissue, not so much of the world before the American Order, but instead of the world before that; in the pre-deepwater-transport era, when the Silk Road acted as interstate, railroad, container ship, and passenger jet all in one. The Turks’ dominance of that era made them so wealthy and expanded their territory so much that they were able to linger as a major power for a full four centuries after the era of the Silk Road ended. Turkey is a living relic of an age long forgotten.

But the Turks are about to come roaring back.

The Turks are ancient, dating back to at least the sixth century, making them one of the oldest consolidated identities of the Middle East and Europe. But that doesn’t mean they’re locals. The original Turks were nomadic horsemen, wandering far and wide across northern China and the Eurasian Hordelands, on occasion raiding, wrecking, ruling, or trading with communities they happened upon, based on personality, season, opportunity, and whim.

Around 1000 AD, one tribe of Turks—the Seljuks—ventured very far from home, pushing through the Caucasus Mountains into the Anatolian Peninsula. What followed was the weakening of the Byzantines, a series of crusades, and the continent-spanning Mongolian tide. It wasn’t until three and a half centuries later that the Seljuks’ successors, the Ottomans, dismounted for good at the gates of Constantinople. The Ottomans put an end to the vestiges of the Roman Empire and Christian Europe’s sense of security all in one go. The Turks renamed the city Istanbul. Within a century, the Turks had become the most powerful nation on Earth.

MARMARA ON LAND, MARMARA AT SEA

Pre-Columbian sailing was a dangerous and limited affair. Sails weren’t yet mastered, so it was slow and required lots of big guys with oars. The ships couldn’t carry much and couldn’t go far at a stretch. In fact, they had to stay close to the shore, stop at night, and hope. Pirates, storms, enterprising locals, and sudden changes in both actual and geopolitical winds could all kill you. Hell, loading the wine wrong could sink a ship. Traders and sailors took such risks regularly, but . . . well, there weren’t many retirement parties for old sailors, and there was a reason a silk outfit was the privilege of emperors.

Well-positioned locations that could also offer some semblance of security and shelter became crossroads. And Istanbul was the ultimate example of a secure crossroads.

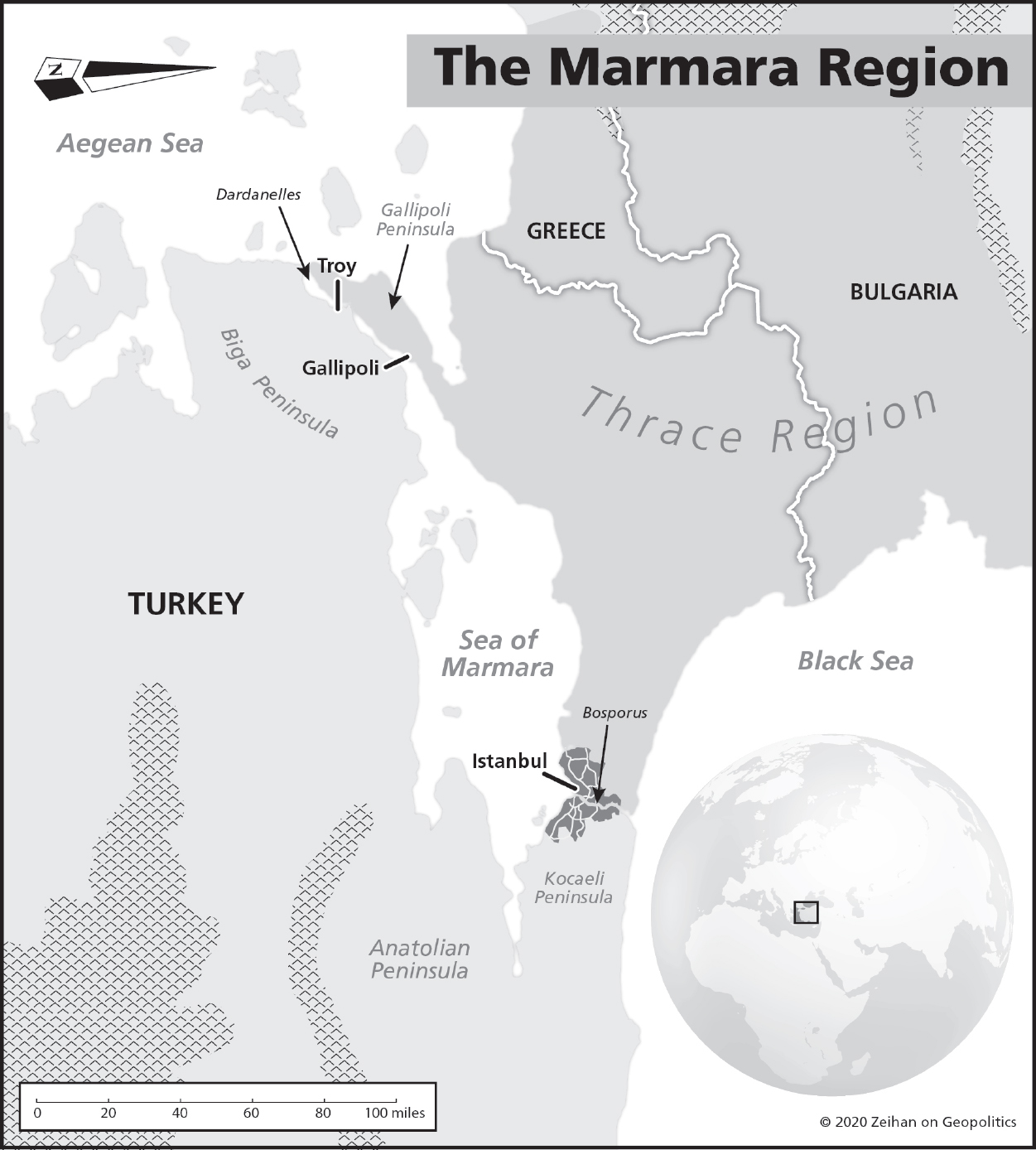

Istanbul sits at the eastern end of the Sea of Marmara. While Marmara is technically not a river, its expanse is so enclosed and calm, it might as well as be one. That’s less the end of the story than the beginning. Sail east from Marmara through the Bosporus and on through the Black Sea and one reaches the Eastern Balkans, the Northern European Plain, and the endless flats of Slavic lands. Sail west through the Dardanelles and one reaches the Aegean, the Mediterranean, the Nile, the Adriatic, and ultimately the Atlantic Ocean.

And it wasn’t just sea routes. During periods of continuity, Istanbul was a safe, central location between Africa, Europe, and Asia. Most Silk Road caravan traffic found its way to and through both the Anatolian Peninsula and Istanbul itself.

Nowhere else on the planet has there ever been as dense a focal point for regional and intercontinental trade. And nowhere else has geography seen fit to enable such a focal point to be defended so easily. To Marmara’s east, the lands of eastern Anatolia form a barrier so severe that they have only ever been crossed by those with Turkish or Persian determination. To the northwest, the rich lands of Thrace give way to the Balkan Mountains. The city has fallen to hostile forces only twice in the past thousand years—once when the Crusaders sacked it in 1204, practically burning it to the ground, and again when the Turks conquered it somewhat more gently in 1453.

In the Marmara region, the Turks hold the most useful and powerful geography in their interconnected region. Marmara’s mild climate, good lands, and peninsular and mountain enclosures make it the perfect site for a wildly successful city-state. But it is more than that. Add omnipresent trade connections to the entire Old World, and that city-state is almost doomed to rule an empire.

The Turks leveraged that geography to dominate everything within a thousand miles. It was a natural progression: secure a physical barrier, metabolize the land it protects, break past the barrier to the next piece of good land, repeat. This took the Turks from Marmara to Thrace to the Lower Danube to the Pannonian Plain and the Crimean Peninsula. From Hatay to Beirut to Jerusalem to the Nile, the Shirak Province, the Red Sea, and the Hejaz. From the Pontic Coast to Zangezur to Mesopotamia, the Persian Gulf, and the shores of the Caspian Sea.

The sprawling empire became the largest on Earth of its time, and if a European coalition had not stopped the Turks at the gates of Vienna during the Ottoman surge of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, one power would have dominated all of Europe and all of the Middle East. History would have looked very different.

But the Turks failed. What went wrong?

In a word, technology.

About the same time the Turks were laying the groundwork for their first attack on Vienna, the technical limitations that blocked everyone from sailing the ocean blue evaporated. Sailors and scholars and tinkerers in far Western Europe learned to construct bigger, stronger ships that could survive on the high seas. They developed the means to sail not just with the winds, but also against them. They figured out how to discern their location, day or night—enabling them to navigate and sail at night. The deepwater era began.

For the Turks, this was an unmitigated disaster.

All the transport limitations that made the Ottoman territories the most powerful in the world—that granted the Ottomans a de facto monopoly on global trade—bled away in a matter of two centuries. Instead of being empowered by their geography, the Turks found themselves imprisoned by it. For centuries the Turks had pushed their borders back until they rubbed up against a barrier—geographic or political—that gave them pause. They would then use their superior economic position to break through that barrier, expanding bit by bit. Unfortunately for the Turks, this also worked in reverse. Maintaining their gains depended upon the Turks’ superior trade-income-fueled economic position.

Since the Ottomans were a river-and-land empire, none of the new maritime technologies helped them one iota. The rise of the deepwater powers gutted the Turks’ trade-based income while also presenting the Turks with new threats. Habsburg Spain’s fleet of the newfangled ships challenged the Turks not just in the wider Mediterranean, but even in the Adriatic and Aegean. Tiny Portugal provided a naval means of transporting Asian goods to Europe that not only bypassed the Ottomans’ land routes completely but enabled the Portuguese to take over production of the fabled Asian goods in Asia, establishing full imperial control over the entire supply chain. And all the while the Turks’ land-based rivals in Europe kept the pressure on.

Stripped of what made it special, facing more foes while garnering less income and suffering greater exposure, the end was inevitable. The Ottoman Empire, the greatest empire of its era, slowly collapsed over three painful centuries. The Northern European powers gutted the Turks in the Pannonian Plain, while the Iberians and English gutted the Turks’ trade income, and the Russians harassed the Turks on the Black Sea and in the Caucasus. By the early twentieth century, the Turks had lost all their Danubian, African, and Caucasian territories. Their World War I defeat ripped away everything but Anatolia and Marmara.

But history wasn’t done. There were more humiliations to come.

First, a condition of the post–World War I settlement forced Marmara and the Turkish Straits open to international traffic. Not only had land-based global trade between Asia and Europe evaporated because of the better logistics of deepwater transport, but now the Turks couldn’t even charge duties on the regional trade passing through the Bosporus and Dardanelles, even though all that trade sailed through downtown Istanbul.

Second, the Soviet rise in the 1920s and domination of Central Europe at the end of the Second World War not only completely locked the Turks out of what once had been some of their richest territories, but also out of what once had been lucrative markets of the Black Sea littoral. The Danube, Dniester, Dnieper, Don, and Volga systems were now all internal waterways of the newly risen Soviet Empire—and Soviet ideology frowned on trading with outsiders.

Third, the creation of Israel and the subsequent Arab-Israeli standoff ended nearly all trade within—much less through—the final economically interesting bit of the former Ottoman Empire: the Levant.

Fourth, and most damning, was the Americans’ new Order. In dismantling the empires and making the oceans safe for everyone, the Americans extinguished any hope of the Turks’ geography mattering at all to global trade. The Americans forced all the world’s waterways to be part of the global commons. If goods can go from any port to any other port without needing to be concerned about either safety on the high seas or persnickety local naval powers, then the specific location of this or that port or coast isn’t all that important. Traders certainly didn’t need a central land-based clearinghouse. What had made the Turks special—critical—evaporated.

Marmara was still nice, and it ensured the Turks remained the most powerful people in their (suddenly much smaller) neighborhood, but no longer was it a kernel of empire. With the world’s long-range commerce now moving on the seas and oceans instead of rivers and roads, Marmara shifted from being the center of the universe to a forgotten backwater. It went from being a bridge to everywhere to a bridge from nowhere to nowhere.

Yet with the Americans’ departure and the Order’s end, Turkey cannot help but thrive.

RESETTING HISTORY

Many—particularly Europeans—like to compare Turkey to the advanced economies to illustrate why the Turks are animals and therefore ignorable. The idea is that the Turkish economy is substandard compared with Northern European norms, with a far heavier emphasis on lower-skilled industries like textiles and basic manufacturing.

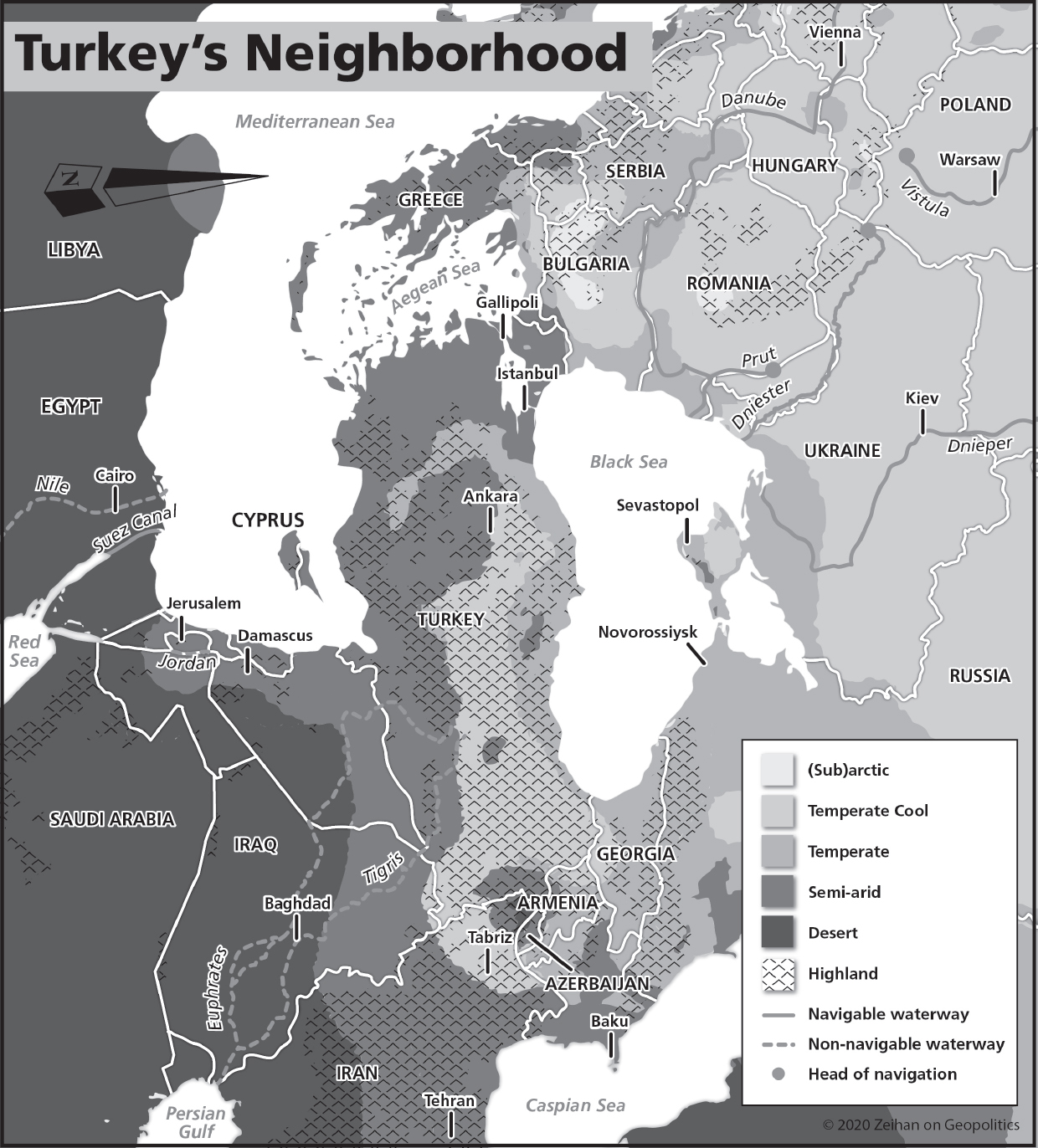

That’s true, but it’s also idiotic. Turkey may have (strong) European tendencies and influences, but it isn’t part of the Northern European Plain. Any comparisons must evaluate Turkey within its neighborhood: the Black Sea Basin, the Eastern Balkans, the Western Mediterranean, and the Middle East. In that neighborhood Turkey—isolated, insular—is already the regional superpower.

Consider the major consequences of the Order’s collapse. All bode well for Turkey.

THE END OF SAFE OCEANS AND THUS OF GLOBAL COMMERCE. Remove the Order, and there is no longer an integrated system of global trade. Instead, the world devolves into a series of national and, in some lucky areas, regional systems. Turkey is among the few countries that have already adapted to the new reality. The Turkish economy is heavily regionalized by global standards, with most trade exposure limited to Europe and its immediate neighbors. Better yet, in a world where the Turks once again assert direct military control over the straits, they can charge transit fees for any through trade. As Turkey is the linchpin in any connections among its neighboring regions, the possibility of making some mad bank looms large.

THE RETURN OF LAND TRADE. It is undeniable that the Order provided the wealth, investment capital, and stability for many countries to build out their physical infrastructure to facilitate local economic development. But when it comes to trade, the vast majority of countries focused instead upon port expansions. Why wouldn’t they? Under the Order, everyone has global reach.

The Order’s end will do more than gut shipping potential and volumes; it will make regional land-based geographies matter a great deal more. Trade that must travel only a few dozen miles is less likely to be disrupted than trade that must cross an ocean. In any system where global maritime transport becomes constrained, land-based transport becomes more viable, particularly within the borders of any particular political authority. Turkey’s physical location makes it the obvious connection point for such land-based transport between Europe and the Middle East, and with roads and rail lines snaking in all directions, Turkey is already prepared for the switchover.

A GLOBAL ENERGY CRISIS. Turkish energy demand weighs in at about 1 million barrels of oil and 4.6 billion cubic feet of natural gas daily, about average for a country of its size and economic structure. Also like its peers, the Turks import almost all of it. But unlike its peers, the Turks don’t have to bend over backward to secure energy. Two of the world’s most important oil transshipment pipes connect Turkey’s Ceyhan port to oil fields in Azerbaijan and Iraqi Kurdistan. Either of them has enough pipeline throughput capacity to fuel all Turkish needs, and with a bit of . . . encouragement from Ankara, neither would face too heavy of a lift to provide the appropriate volumes. Should the Turks build one more midsize refinery anywhere along their lengthy coastline, their oil-products problem vanishes without taking a drop of Russian or Saudi Arabian crude (which could well remain available to the Turks). Natural gas is a bit more complicated, Turkey having an unhealthy dependence upon Russian imports. Yet new lines to Azerbaijan, the possibility of a short-haul line from Iraq, and a burning Russian desire to not piss off the Turks while Moscow is jousting with Stockholm and London and Warsaw and Berlin takes the sting out of the question.

As a fallback, the Turks have just enough crappy coal to bridge themselves to more geopolitically reliable (i.e., non-Russian) energy supplies.*

THE FALL OF THE RUSSIANS. The Soviets didn’t want to trade with the Order, and the Americans didn’t want the Order trading with the Soviets. The ideological and strategic conflict generated extreme economic spillover, producing consequences that sucked for the Turks (much of their former empire fell on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain). But with the Cold War’s end and the reopening of the former Soviet space, trade from Europe, the Balkans, the Caucasus, and the Hordelands is once again flowing to Turkish ports, into Marmara and beyond to the Mediterranean. Even in the unfortunate circumstance that Turkey ends up crossing swords with the Russians, there will be far more trade on the Black and through Marmara than there ever was under the Order. Without American-enforced freedom of the seas, the Turks can return the Bosporus and Dardanelles to their normal status of being internal waterways. Everyone will have to pay the Turks to sail through. At least in part, the income stream that made the Ottomans so wealthy is coming back.

A CONFLICT IN THE PERSIAN GULF. The Middle East is replete with examples of two local powers rising simultaneously, clashing, and containing each other’s ambitions and opportunities to the point that they massively weaken each other. Then a third power comes in and sweeps the board. Saudi Arabia and Iran both fancy themselves regional powers. As the Turks have far more military and economic capacity than the pair combined, the Turks find the Saudi-Iranian battle for influence rather adorable. What Turkey does not find cute is the fact that the Saudi-Iranian battles in Syria and Iraq are starting to harm Turkish interests: militants in Syria, threats to energy supplies from Iraq, swarms of refugees from both. The Turks reserve the option of interfering in the Saudi-Iranian fight and settling it however they choose. The real fireworks of the Iranian-Saudi confrontation will happen in densely populated Mesopotamia—an area not of core concern to Ankara. The Turks could push into Iraq as far south as Baghdad within a couple of months. Similarly, with a week’s worth of effort, the Turks could shatter the entire Iranian and Saudi position in Syria, withdraw the next day, and evaluate the smoking wreckage from a distance.*

END TO THE BAR ON IMPERIAL PREDATION. Deepwater navigation turned Turkey into a backwater, and the Order turned Turkey into a nowhere, but an era of Disorder means Turkey matters again for all the same reasons that it mattered at the Ottoman Empire’s height. Turkey is transformed from a nothing power into, if not the center of the world, at least the center of its region. And while Turkey was never one of the grand, globe-spanning, naval-based empires the Americans were thinking about when they crafted the Order, an empire it certainly once was. Once again, Turkey will be able to expand outward from Marmara, seeking territories and opportunities.

BACK TO THE FUTURE

The Turks’ post–World War I shattering was just as traumatic for the Turks as any empire’s ruin is to its core citizens. The military crumbled, the economy collapsed, the political system splintered, and the Turks’ sophisticated culture—rich with hospitality and tolerance—splintered inward. Reformers attempted to overhaul a sclerotic bureaucracy that had little to do but absorb resources. Minorities facing starkly reduced economic security rebelled, sparking violent responses from the Turks, culminating in, among other things, the Armenian Genocide. Foreign agents were able to tap into the resentments to achieve military goals, the most romanticized one being Lawrence of Arabia. When it was all over, the empire had done more than die; it had dissolved into chaos. At one point, it was so bad that pieces of Anatolia weren’t controlled just by the French and British, but by the Greeks.

Normally when an empire collapses, it is either occupied and restructured by outsiders (like Germany and Japan after World War II) or so wholly immersed in a new reality that the transformation occurs very quickly, often with extraordinarily painful impacts upon the citizenry of the home state (such as the British Empire’s collapse in World War II, or Russia after the Soviet Union’s dissolution). A truly destroyed empire can rarely dwell on its defeats in privacy, shielded from the world, to map its way forward.

However, that’s precisely what happened to the Turks after World War I. The Soviet rise barred commerce and contact with former imperial possessions to the northwest, north, and northeast. The hostile, arid geography of the Middle East combined with the rise of mutually hostile and/or totalitarian governments that cared little about economic development or trade walled off the south. The only “open” border the Turks had was with Iran, the adjoining territories being physically rugged and far removed from the two countries’ capital regions, both in terms of distance and culture. Turkey was sequestered, and in its isolation, it obsessed over what it meant to be a Turk.

Two competing visions emerged.

On one side were the secularists, who sought a modern Turkey that would be a completely separate, independent pole in international politics. They rejected the cosmopolitanism for which the Ottomans were known in favor of a new ethnic Turkish ideal. Islam played no role in the secularists’ identity, at home or abroad. The wealth of Istanbul was embraced, and economic and cultural interaction with Europe was encouraged, but no one confused such acceptance with multiculturalism or a celebration of “lesser” peoples, like Greeks or Armenians. It went so far as to assert that Kurds, who today comprise one-fifth of the Turkish population, never even existed in the first place.

Opposing the secularists were the Anatolians, who sought to retain many of the Ottoman system’s cultural norms—particularly its religious identifiers—and use those characteristics to bind the new Turkey tightly to their co-religionists throughout the Arab world. The Anatolians saw themselves as the logical heirs to Ottoman grandeur and viewed the shift of the capital to the interior city of Ankara as less a (necessary) strategic move to insulate the government from outside powers than a means of transforming Turkey’s political life into something more akin to the countryside. Economic links were a means to a cultural end, rather than ties that bind Turkey to Europe. Deep, unrelenting efforts were made to transform liberal Istanbul into an extension of the culturally conservative interior.

It was the greatest cultural fight the Turks had wrestled with since swapping their saddles for houses after the conquest of Constantinople a half millennium before. From the close of the First World War until century’s end, the argument over “who are we?” raged. But history has a way of overtaking events. Between the Cold War’s end and the Order’s impending demise, the Turks’ context evolved, and their existential identity crisis evolved with it:

- You didn’t have to agree with Osama bid Laden’s politics or policies to understand that the 9/11 attacks vividly demonstrated that Islam was relevant in global affairs. For the Turks who used to lead global Islam, but who had been divorced from the world for three generations, the attacks pressed home the idea there was a mantle out there waiting to be picked up.

- The Soviet Union’s collapse opened up Turkey’s entire northern horizon. Trade began flowing through Marmara again. The Turks realized the world was re-interfacing with them once again whether they were ready or not.

- The Soviet collapse was a partial motivation for Turkey’s effort to join the European Union, as several of the former Soviet satellites and republics in the membership queue were also former Ottoman provinces. The secularists saw membership as a way to entrench Turkish modernity. The Anatolians saw it as a means of guaranteeing democracy. Once it became apparent that the EU would never admit Turkey, both Turkish factions reconsidered what it was they were after.

- For the Turks, the United States’ 2003 war in Iraq was notable not for its outcome or its nearness to Turkey’s borders, but instead for the fact that the Turkish parliament voted to refuse the use of Turkish territory by American forces. Turkish nationalism surged, now flavored by a weird cocktail of local militarism, pro-Islamism, pro-Arabism, and anti-American feeling. The secularists and Anatolians discovered themselves . . . agreeing on things.

- With the Turks sitting out the Iraq War, the Americans found a new ally in northern Iraq’s Kurdish groups. This was a problem for Ankara. Not only were there more Kurds in Turkey than Iraq, but the Turks had just recently finished fighting a thirty-year civil war over Kurdish separatism. Even worse, the Kurds in time rose to be the Americans’ ally of choice in Syria as well. Such betrayal (in the Turks’ eyes) functionally ended the American-Turkish alliance, while provoking both secularists and Anatolians into seeing Turkey as beset by an ever-more-distant superpower. America’s abandonment of the Kurds in late-2019 hardly restored the US-Turkish alliance, although it did result in a bit of an upgrade from seething hostility to cold distrust.

After seventy years of culture war, the two factions found themselves intermingling and eventually merging in the personality of Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Many of Erdogan’s foes see him as the quintessential Anatolian—wanting to use Islam as a pillar of Turkish identity and policy, and disdainful of connections to the West. That’s true. But what is also true is Erdogan’s embracing of many of the secularists’ traits: a rejection of multiculturalism, a willingness to bash heads when elections don’t go the way they are “supposed to,” the idea that Turkey is a strong and independent power.

The new Turkey combines the cultural grandeur, muscle tone, and arrogance of the Ottoman Empire with the religious leanings, disdain for secularism, and distrust of the Western world of the Islamists, and with the authoritarian, chauvinistic, and ethnic parameters of the secularists. If the goal is a peaceful, multicultural, globalist society, it’s not quite the worst of all worlds, but it isn’t far off.

Most significant of all, the Turks are late to the game of becoming an ethnically defined nation-state. That’s extraordinarily dangerous. When a group starts defining itself in terms of ethnic purity, sketchy things tend to happen. The French, who started us all down the road toward fusing our ethnic identities with state power, also started us down the road of the various consequences: the Terror and the Napoleonic Wars. When the Germans and Japanese followed, we got the World Wars, the Nazis, the Holocaust, the Rape of Nanking, and the Bataan Death March. Mentally and culturally, Turkey today is in a condition very similar to that of late-1700s and early-1800s France, and early-1900s Germany and Japan—flaunting a brash, bold, unapologetic nationalist identity like a teenager on a meth high. Time will grind such thinking down into a more pragmatic form, but time takes, well, time.

Erdogan’s party—the AKP—rose to power in 2002, granting Turkey a government willing to look beyond the parameters of the American relationship just as the Americans were starting to view their strategic picture from new angles. Fast-forward to 2020, and the Americans are unwinding their global strategic commitments at the same time the Turks are getting over their shyness in international affairs.

The Turks are excited about exploring what it means to be a nation-state just as the world is shifting back into empire mode, and the Turks have the perfect topography to be one of those empires. That all but hardwires in Turkish conflict—strategically, economically, politically, and racially. What with a fracturing Europe, a collapsed Middle East order, and Russians on a warpath paved with desperation, Turkey’s entire periphery is in wild motion, and the Turks are about to leap into the storm.

Which begs the question: which way will the Turks jump? There are opportunities at every point of the compass.

THE FRONT YARD: BULGARIA AND ROMANIA

For the Turks, the brightest spot in this emerging world is the Eastern Balkans. The reasons are legion.

Without the Americans anchoring NATO and the European Union, most of the Continent becomes a free-for-all as once-imperial powers compete for regional influence over matters political, economic, cultural, and military. But the portions of Europe closest to Turkey—the Eastern Balkans—are a world away from such competitions.

The European Union did not admit Bulgaria and Romania to their membership on the same timetable as their wealthier former Soviet satellites for good reasons. Their infrastructure is clearly inferior. Organized crime penetrates throughout their societies. Corruption bleeds through into much of public life. Their cultures are not as entrepreneurial.

But mostly it was about physical access.

The Lower Danube’s littoral zone is largely isolated from everyone else in Europe. To the west of the Lower Danube, a series of knotty peaks where the Balkan and Carpathian ranges meet blocks nearly all transport options aside from the Danube itself. The point where the Danube forces its way through those knots is a particularly rugged series of cliffs. These Iron Gates inhibited all transport between the Eastern and Western Balkans since antiquity, and it was only with deeply expensive Soviet reengineering of the river, completed in the 1970s, that the Danube became safely navigable year-round. Even that advance was set back two decades when the Americans destroyed most of the Danubian bridges in Serbia during the Kosovo War. The Eastern Balkan pair is not as integrated into Europe now—a decade after EU and NATO membership—as closer countries, like Poland, Latvia, and Hungary, were before EU and NATO membership.

The relative isolation has its perks. Bulgaria and Romania’s relative poverty compared with the rest of Europe enables the Bulgarians and Romanians to switch partners with relative ease.* Because the Turkish Straits are the best maritime connection between them and the wider world, there’s not much wiggle room in choosing a post-Order partner.

The pair bring a lot to the table. Both Bulgaria and Romania are significant agricultural exporters, and between the two and Turkey, nearly every climate zone that generates foodstuffs is represented. The result will be a regional supermarket for nearly every type of food humans can grow: wheat out of Turkey’s Mediterranean coastal climate, corn and soy from continental Bulgaria and Romania, oilseeds from Romania’s drier east, fruits of various types from the three countries’ uplands, citrus from the Black Sea coasts, grapes from the three’s mountains, and so on. In a world where global trade breaks down, and once everyday luxuries become exotics, the extended Turkish family will have all it needs close at hand—and complete food security to boot.

Above all else, the Bulgarians and Romanians will be willing. Both Sofia and Bucharest realize that their chances for charting their own destiny—even if the two allied—are zero. The Balkan and Carpathian Mountains box them in, the Russians dominate their northeast, the Turks their southeast, the Germans their northwest, and any access to the wider world requires the purposeful and ongoing permission of multiple other powers. They are quintessential examples of the sort of countries that have no long-term hope of survival outside of the global management structures of the Order.

That is, they have no chance without a sponsor. On their own, they are prey, but partner them with the Turks, and their position shifts from pathetic to enviable. They gain entrée to a country with energy security, a market twice the size of their own combined, and access to the Mediterranean Basin—something otherwise impossible. Defense guarantees from Turkey may not have the gold-star value of those from the United States, but the Turkish military is both competent and close by. Best be on its good side. Especially if there’s a risk in the Disorder that the Russians start acting like Russians again.

GO FOR THE THROAT: UKRAINE AND BEYOND

The former Soviet Union abounds with threats and opportunities for Turkey, but none glow so bright as the Russian death throes. They raise the distinct possibility that the Turks will seek to nudge their old rival toward oblivion. Such a strategy is far from risk-free—the Russians have one of the world’s most powerful air forces and a hefty nuclear arsenal—but the benefits would be legion.

Let’s start with the benefits:

- During the Cold War, the Russians controlled all the territories to Turkey’s north, contributing to Turkey’s slide into strategic oblivion and economic mediocrity. Even now the Russians’ presence dampens the region’s economic horizons. Their penchant for hijacking trains in and shooting down passenger jets over Ukraine severely limits the potential for trade. Removing the Russians would drastically change the fate of those living along the Dnieper and Dniester rivers. Unlike Russian rivers, the Dnieper/Dniester pair flows south instead of north and lies in more temperate zones. There is no ice-dam danger, and both remain navigable nearly year-round.

- In Ottoman times the Ukrainian rivers were robust commercial arteries that pushed Ottoman interests deep into the western Hordelands, but under Russian domination both have become anemic, corrupt, circumscribed, and dreadfully poor. About the biggest complication is that Ukraine and Turkey have similar steel industries and are traditional competitors. (In a world of shortfalls, however, today’s competitor could be tomorrow’s oligopoly.) Bulgaria and Romania might be solid choices for a Turkey seeking economic opportunity, but Ukraine—with more people, a huge metals industry, and a larger agricultural production than Bulgaria and Romania combined—would be a close third.

- Azerbaijan would be fourth. While there isn’t a lot that happens of economic interest anywhere in the Caucasus, there is one large exception: the Caspian oil fields of Azerbaijan. By themselves they export over five hundred thousand barrels per day, and there is sufficient installed infrastructure for double that amount to transit through Georgia to Turkey. Russia is most certainly the dominant military, economic, and cultural power in the Caucasus. Armenia is in essence a satellite state while Russian forces maintain secessionist enclaves on the Georgian side of the Greater Caucasus Mountains. Yet Turkic peoples throughout the region still look to the Turks for succor. Removing Russia from the board raises the tantalizing probability that Turkey would be the first power of the Caucasus. Again.

- Russia isn’t all that . . . nice. The same intelligence services that are so good at pacifying Russia itself and Russian-occupied territories are just as skilled at stirring up trouble in other places. In ages past the Russians encouraged Iranian belligerence against not just the Americans, but also the Turks. They’ve put flies in the Azerbaijani ointment. They’ve formally backed Armenia with weapons and intelligence. They’ve worked to hinder—even sabotage—pipeline projects that would bring Azerbaijani energy to Turkey. They’ve deliberately spawned humanitarian crises in Syria, deliberately flooding the Turkish border with refugees. And they’ve stoked Kurdish rebellions in Turkey proper in order to limit Turkish options and keep Turkish power pinned down. Admitting all that might be ideologically inconvenient to this or that faction of the current Turkish government, but for those aware of imperial, Cold War, and recent history, calling Russia a friend to Turkey requires substantial mental creativity.

The kicker is, Turkey doesn’t have to win for Russia to lose. The only outcome of the brewing contest between Russia and Europe that extends the life of the Russian state is one in which Russian forces consolidate control of the Baltic Coast and the Polish Gap as well as the Bessarabian Gap, all of Ukraine, Moldova, and the Caucasus republics. Failure to achieve all these goals leaves the Russians unanchored and engaged in a war of numbers and/or movement that they cannot possibly win.

Anything shy of total success would also gut the Russian state’s income. Russia’s competition with Europe will end meaningful oil and natural gas exports via the Baltic Sea and North European Plain. The only other large-scale route is southwest via the Black Sea and Turkish Straits. Even a minor military conflict with Turkey would utterly end Russia’s ability to export oil and natural gas to the west, removing it from the list of significant energy exporters (it currently ranks number one for combined oil, natural gas, and petroleum products, with oil and natural gas sales being the government’s top two sources of income).

While predicting tactical moves in a strategic conflict that has yet to begin is a bit like playing darts blindfolded while doing tequila shots, the optimal time for Turkish action would be once the Russians become fully committed against the Northern Europeans. At that point the Russians would have fewer forces to spare to a front in the south, vastly improving the success rate of what would have to be a sizable amphibious assault.

The optimal place would be the Crimean Peninsula, Turkish control of which would eliminate the only meaningful Russian naval presence on the Black Sea, turning it into a Turkish lake. Because the Crimea’s link to mainland Ukraine is only three miles wide, defending it from a mainland assault would be easy. While Turkey’s air force couldn’t hold its own against Russia in a one-on-one fight, Russian forces would already be engaged against every country that borders the Baltic Sea. It wouldn’t take much Turkish strike capacity to sever most of the Russian army’s supply lines into western Ukraine and even Belarus. And the Turks would have local help: the Crimea’s Ukrainian and Tatar minorities would likely view the Turks as liberators from Russian occupation.

The problem is, all this is very all-or-nothing. Russia faces nothing less than an existential crisis; it is fighting for its very survival. The parts of the region the Turks see as the most lucrative are those that the Russians view as the most strategically essential. Even distracted and off-balance, the Russians have the capacity to strike back. Russia already has thousands of airmen and soldiers in not just the Crimea, but also Armenia and in secessionist regions in Georgia. Turkish intrusion into the Crimea or Azerbaijan would so change the facts on the ground that the Russians would feel they have no choice but to use every tool at their disposal, from prompting a Kurdish insurrection in eastern Turkey to a sponsoring an Armenian assault into Georgia to bombing Istanbul itself.

High reward brings high risk.

THE BACKYARD: IRAQ AND SYRIA

The Turks’ first foray into the Middle East predates their calling themselves Turks. The Seljuks toured real estate in Mesopotamia and the Levant before they ultimately settled on the better neighborhood of Marmara. Later, after the failed assaults on Vienna, the Ottomans found it easier to expand into areas their forebears had explored in centuries previous. The empire shifted from its Occidental orientation to an Oriental one during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, earning it territories that comprise contemporary Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq.

The problem with contemporary Turkey returning to the region is that it isn’t clear where it can stop. There is no equivalent of the Crimean isthmus or the Iron Gates where Turkey could stop to digest a small bite of territory. The fact is that much of the imperial debris in the region is from the Turks’ own empire, and any sane planner in Ankara must look south with at least a concerned wince. This isn’t a region you expand into because you want to; you go in because you fear what will happen if you don’t. Which is precisely why the lands to Turkey’s south are on Ankara’s radar.

Ultimately, it’s an issue of security. The vast majority of Turkish territories today are not the rich lands of the Lower Danube, but instead the arid, rocky uplands of Anatolia. The farther east one travels on the peninsula, the higher, drier, sharper, and less productive the terrain becomes. But while this argues against the Turks settling in it, it both provides an excellent block against invasion and provides within Turkey precisely the sort of territories that house rebellious, persnickety ethnic groups. Russia has its Chechens, Lebanon the Druze, Spain the Basques, America has West Virginia, and Turkey has the Kurds. The entire southeastern quadrant of Anatolia is a Kurd-majority region, home to half that ethnic group’s total population, with the rest distributed in the border regions of Syria, Iraq, and Iran.

The Kurds of Turkey have been fighting an on-again, off-again insurrection against Turkish power since the end of World War I. Its hottest flare—claiming over thirty thousand lives—was in the 1990s. One of the most effective means the Kurds have of fighting is to seek succor and basing with their co-ethnics in Syria, Iraq, and Iran. And because the Turkish, Syrian, Iraqi, and Iranian governments are all run by different ethnoreligious-linguistic groups, they don’t care much for one another and have often been willing to encourage Kurds in the others’ lands to rebel—so long as they do so on the other side of the border.

Turkey often finds itself flat-out invading Syria and especially Iraq to pursue fleeing Kurdish militants and rip up Kurdish bases. A more permanent assault that left Turkey in control of Syria and Iraq’s northern territories would bring over three-quarters of the Kurdish population within the Turkish system. There would still be unrest and violence, but direct, permanent occupation would enable the Turkish state to bring all its many tools to bear.

Conquering Iraqi Kurdistan would come with some notable fringe benefits. Permanently stationing Turkish troops within a short commute of Baghdad would sharply refocus minds in both Tehran and Riyadh. Neither Middle Eastern power can hold a candle to Turkish military might, and seeing Turkish troops much closer than the horizon would encourage both to take Turkish preferences into account throughout the region.

There’s also the energy question. Iraqi’s Kirkuk oil region is less than two hundred miles by road from the Turkish border. An improved security environment complemented by some engineers who know what they’re doing could easily coax enough oil out of the ground to meet Turkish demand in full. Even better, the Kirkuk region already sports preexisting pipeline capacity to Turkey capable of carrying nearly twice that much. Technically and logistically, a Turkish southern expansion could easily bring the entire producing infrastructure under Turkish control. The “only” complication is what the Kurds might do.

Syria is messier, in large part because it encapsulates everything that makes the Middle East dysfunctional: A coastful of collaborating minorities. A vast interior of impoverished Sunni Arabs. Sharp, forested mountains full of hidey-holes. It’s the perfect recipe for political instability and economic dislocation. And it’s on fire.

The territory that is today’s Syria has suffered hugely under the global Order. Pre-Order interior “Syria” was a caravan route throughout lightly populated terrain, dotted with a quartet of ancient oasis cities—Aleppo, Homs, Hama, and Damascus. But the Order’s freeing of the global ocean combined with its shattering of the empires ended the caravan trade while erecting hard political borders. The people of Syria could no longer trade for food; they had to find something else.

On the one hand, the Syrians exported crude oil and used the subsequent currency earnings to import food. On the other, they transformed the desert to a degree possible only in the Industrial Age, drawing water from the Euphrates to grow wheat. It worked for a while. But the Syrian population expanded to the point that the oil exports stopped, and a drought (among other factors) in 2011 wrecked nationwide irrigation. The Syrian Civil War, first and foremost, is a civilizational collapse with its roots in national starvation.

Which is damnably inconvenient for a newly emergent Turkey. Even if the Syrian Civil War ended today, there isn’t enough water and oil to feed the population. Syria will not—will never—recover. Rivers of Syrian refugees into Turkey are the new normal, for they’ve nowhere else to flow. Lebanon already has more refugees per capita than any country in human history. The Israeli border is a wall of mines and barbed wire. Jordan is even dryer than Syria (and already has over seven hundred thousand refugees, about four hundred thousand more than the poor country could be expected to support without its fragile political system cracking). The Saudi and Iraqi borders are hard desert. That leaves Turkey. And the only way the Turks can truly manage the situation and keep the migration flows manageable is to go in and take over the whole damn place.

THE LONG PLAY: THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

A successful Turkey needs a navy nearly as much as it needs an army, and on no side is a navy more relevant than to Turkey’s west. In part, this is because the magic of sea travel made it easier for the Ottoman Empire to integrate with Europe and North Africa than the Caucasus, but mostly it is because of the countries most pathologically paranoid about a Turkish return.

Consider the Aegean Sea and northeast Mediterranean to be Turkey’s Gulf of Mexico. The islands of Greece—islands the Europeans transferred forcibly from the Ottomans to the Greeks as part of the post–World War I settlements—are like the various islands of the Caribbean. Cyprus a sort of Cuba. Greece and its myriad islands have to be brought under Turkish control, or they will always threaten Istanbul and the trade that flows in and out of Marmara. Similarly, Cyprus is too big and too close to Turkey for Ankara to tolerate the possibility of a foreign power on the island. So the Turks invaded in 1974, conquered the island’s northern third, and have been there ever since.

Conquest of Greece and securing the Aegean Sea would insulate mainland Turkey from regional naval powers, even those as powerful as the United Kingdom or France. And since those two European nations are likely to have bigger fish to fry closer to home, odds are the Turks wouldn’t face many extra-regional challenges if they try.

Turkey’s problem is not military. On paper, Greece maintains a huge air force expressly to keep the Turks at bay, but with Athens’ financial implosion, the Greeks haven’t maintained their jets for a decade, much less managed to get their pilots much flight time.

Indeed, both Greece and Cyprus are likely to fall without any help from the Turks. Both import all their energy and nearly all their food. Both are economic basket cases whose existence continues only because of an ongoing—and resentful—financial drip-feed from the European Union.

The problem is the last thing the Turks would want responsibility for is another Syria. With the fall of the European Union and the general breakdown of maritime economies the world over, Cyprus and Greece are about to decivilize, albeit likely (hopefully) not so violently as Syria has managed to.

If the Turks move west, they’re likely to attempt to split the baby: seize Cyprus outright along with the bulk of the Greek islands but leave mainland Greece to wither on the vine. That makes Turkey responsible for a manageable 1.5 million occupied Greeks and Greek Cypriots rather than 12 million.

From the Turkish point of view, such territorial gains would be more than enough motivation to move west. Both the Aegean Islands and Cyprus were some of the Ottomans’ oldest territories. The Turks lost control of them only because the Europeans—primarily the British, French, and Greeks—were so enthusiastic about carving up the Ottoman corpse at the end of the First World War.

But there is more at stake here than simple historical grievance.

In any post-Order world, maritime shipping will be more difficult and less safe, while ships will have no choice but to travel faster and do so with smaller cargos. Add instability and conflict in the world’s two largest oil-exporting regions—the former Soviet Union and the Persian Gulf—and the result is lower oil supplies combined with sharply higher and far more erratic oil prices.

Turkey is on a short list of countries that enjoy some insulation from that environment. It is hardwired via pipelines to both former Soviet and Persian Gulf supplies, providing the Turks with more than enough for their needs. Pretty much everyone else needs to keep importing crude oil by tanker. Traditionally, one of the world’s three biggest oil shipping routes is from the Persian Gulf states to the Red Sea, through the Suez Canal and Suez bypass pipelines, into the Eastern Mediterranean and on to Europe. In a post-Order world, the Mediterranean transforms from being a safe and unified European shipping channel to a fragmented and highly contested maritime environment—just as it was from the dawn of recorded history to 1945.

The Turks are not blind. If they succeed in resecuring control of the Aegean Sea and Cyprus, they will de facto control the entire Eastern Mediterranean Sea.* Expect to see Turkish military vessels escorting oil tankers that didn’t request escorts. Think of it as an echo of the old Silk Roads. The Turks command the route’s middle sections and so can take a bite out of the commerce as they see fit.

And that will trigger a response. With increased Turkish naval activity in the Eastern Med, the likelihood of Egypt jacking up transit fees for Suez, and the increased difficulty of sourcing crude oil in general, many European nations are likely to view Suez and its oil flows with covetous eyes. France is by far the country with the greatest propensity and capacity to move in force.

That puts Egypt firmly and permanently in the Turkish camp, while also putting Israel on notice. A marriage of convenience with Turkey gives the Israelis local security under a regional hegemon and all the crude they could ever need. The irony of the Jewish state being under Muslim protection and using Muslim oil is not likely to be lost. The other option would be for Israel to side with France. That introduces a great deal of risk but also gives the Israelis a hedge against the local Middle Eastern superpower. Luckily for the Israelis, they are used to difficult choices.

SWING FOR THE FENCES: IRANIAN AZERBAIJAN

Russia and Turkey are not the only major powers with their fingers in the Caucasus. Any increasing Turkish presence there would be met with hostility in Iran. Such hostility would be far more visceral than even Russian opposition, for while the Russians see the Caucasus Mountains as an ideal border and buffer, the Iranians see the region as a twofold threat.

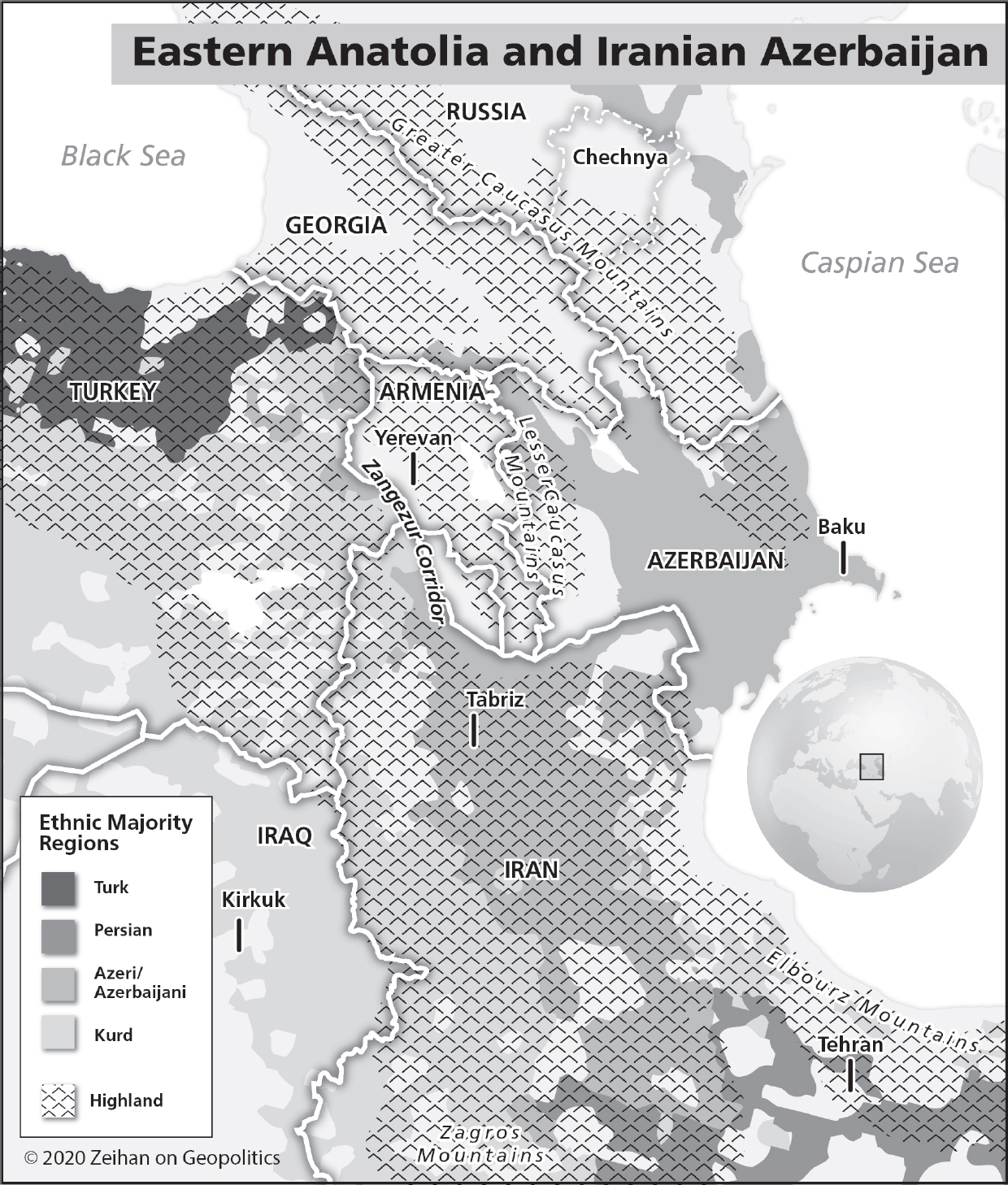

First, the Lesser (Southern) Caucasus are not nearly as geographically impressive as the Greater (Northern) Caucasus. The Greaters are, as the name suggests, pretty great. Tall, steep, imposing, and pushing east and west to the very shores of the Caspian and Black seas.* The Lessers are somewhat less great. More of a knotty plateau than true mountains, the Lessers sport several fairly easily negotiated access points that link the intra-Caucasus region of Georgia and Azerbaijan to the highlands of Anatolia and the Zagros Mountains.

Several valleys connect throughout the region, but the most important by far is the Zangezur Corridor, which accesses Turkey and Armenia and Azerbaijan and Iran. Should a single power prove able to control the Zangezur in its entirety, it could march on the other three with relative ease. Therefore none other than Joseph Stalin himself redrew the region’s borders in the 1920s, splitting the Zangezur roughly equally among Turkey and Armenia and Azerbaijan and Iran, with the express intent of maximizing strife among the four. Stalin was pretty good at this sort of thing. Any serious push by Turkey into the Caucasus means putting Turkish troops in the Zangezur—near the Armenian capital of Yerevan as well as within striking distance of the Iranian heartland.

As if that weren’t bad enough for the Iranians, the second factor is even worse for them.

The second most numerous people in Iran—next to the Persians themselves—are the Turkic-speaking Iranian Azeris, ethnically identical to the Azerbaijanis of the namesake former Soviet republic, who live almost exclusively near Iran’s borders with Azerbaijan and Turkey. There are more Iranian Azeris living in Iran than there are Azerbaijanis in Azerbaijan itself. The geographic center of their population is the city of Tabriz, less than a hundred miles from the Zangezur access point.

A Turkish move against Iran would be far from simple. It would require a flat-out occupation of northwestern Iran despite the direct, unrelenting military conflagration that would come from it. While Iran’s jetless, tankless, outdated, sanction-starved military is laughable compared with Turkey’s modernized, NATO-armed, and increasingly self-supported complex, this is about more than order-of-battle comparisons.

First, the terrain is mountainous, not only making northwestern Iran easier to defend but also providing precisely the sort of advantages that infantry would require in a battle against mainline tanks enjoying air support. The Turks could still carry the day, but not quickly or without considerable bloodshed.

Second, there’s the “home-field advantage” defenders have when their homeland is under attack. Moreover, Iran’s Persianification efforts are literally millennia old. Because the Azeris are Iran’s largest minority group, extra effort has gone into grinding as much of the Turk out of the Azerbaijanis as possible. While most Iranian Azeris certainly still consider themselves of Turkic descent, that is not the same as saying they consider themselves anti-Persian or fully Turkish. For example, the dominant religion among Iranian Azeris is Shia Islam, the same as the Persians, and not the Sunni Islam practiced in Turkey. The Turks will certainly enjoy the support of a large fifth column in any invasion, but they will not be categorically welcomed. There will be plenty of resistance, and not only from the Persians.

Third, Iran has tools beyond its military. Iranian intelligence assets at any given time are active in Azerbaijan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, the Palestinian Territories, . . . and Turkey. In times of Turkish-Iranian hostility, Iran has worked overtime to stoke tensions and militancy among Turkey’s many mountain minorities and political factions, most notably the Kurdish population. And because any Turkish assault on Iran would need to pass through Turkey’s own Kurdish region, Iran would undoubtedly work to set that entire region on fire. Even if Turkey could seize northwestern Iran, holding on to it would be a whole other problem.

This whole scenario seems like more trouble than it’s worth, but it is worth considering, for two reasons.

First, most of Turkey’s border regions have interlocking issues. Going into Romania can lead to confrontation with Russia, which can lead to intervention in Ukraine, which naturally leads to competition in Azerbaijan, which means Turkish forces in Zangezur, which means Tabriz is in play. Whoever has controlled Marmara, their top problem has always been the spiraling combination of seemingly unrelated topics and theaters into a royal, unentangleable mess.

Second, Turkey is still figuring out not only what it wants, but who it is. In 1995 Turkey was a hard-core authoritarian military regime with a healthy civil society but accountants who might as well have been Italian. In 2005 Turkey was a mildly Islamic democracy run by economic technocrats who might as well have been German. In 2020 Turkey’s democracy is dead, and the country is on a rapid slide into authoritarian, ethnic-based populism that looks practically Russian. Considering that trajectory, the emergence of an ethnically driven strategic policy that takes Turkey directly into Azerbaijan—both independent and Iranian—isn’t so far-fetched.

THE VOTES OF OTHERS

None of these is an obvious choice. Economically, the Balkan advance makes the most sense. Ethnically, it is difficult to argue against grabbing the Azerbaijans. Going southeast solves both an internal security issue as well as an energy dependency. Taking Cyprus would be a strategic coup and give the Turks leverage against all of Europe. Grabbing Crimea would condemn the Turks’ most powerful historical foe to dissolution. What is clear is that Turkey has options—and that includes options for the fights it will pick.

Options make the foreign policy of contemporary Turkey seem erratic. Within the past decade, the Turks have offered Armenia peace and threatened it with invasion, funded some infrastructure in (independent) Azerbaijan while also haranguing Baku on other projects, cozied up to Russia economically but shot down a Russian jet, alternately let Syrian migrants flow through its territories to Europe and stopped them, encouraged Islamic militants to flow into Syria and then invaded Syria to kill them, encouraged Iraqi Kurds to ship their oil through Turkish territory while invading Iraqi Kurdistan, and competed with the Iranians for influence in Azerbaijan and Iraq while also helping the Iranians bust US sanctions.

If this seems a bit schizophrenic, that’s because it is. Turkey’s geography is complex. What works for one border doesn’t work for others. What might have worked during the Cold War is different from what works during the Order’s dying days is different from what will work in the Disorder. And once Turkey chooses a path, the calculus shifts again.

It will get messier.

Unfortunately for the Turks, they are not the only people with a say in the matter. While Turkey easily has the power to go any direction it wishes, it has nowhere near the power to go every direction it wishes. It will have to choose, and others have the opportunity to shape the decision.

The Europeans and Russians wouldn’t like the Turks moving into the Eastern Balkans. The Russians and Iranians wouldn’t like the Turks moving into the Caucasus. The Iranians obviously wouldn’t be keen on the Turks moving into Iranian Azerbaijan, while neither the Iranians nor the Saudis would like to see Turkish troops moving into Iraq at all. Turkish forces there would be able to cut off any Iranian assault on Saudi Arabia in a day, while the last thing the Saudis want to see on their northern border is a functional state and military.

What’s a bit weird is, everyone would like to see the Turks in Syria.

If Turkey is forced to deploy a hundred thousand troops or so to stabilize Syria, it will largely occupy Turkish strategic attention for years, absorbing any military bandwidth that might have been used to venture into Greece or Romania or Crimea or Azerbaijan or Iran. It would also enable Russia, Iran, and Saudi Arabia to pin Turkey down more firmly by spawning violence in the occupied areas. (The Saudis, in particular, have a vested interest in nudging Syria’s decivilization process along.) Even the Europeans would see this as a good thing: if Turkey is forced to occupy Syria, the Syrians are more likely to stay in Syria.

The Turks know this, but that’s not the same thing as saying they won’t fall for it. The Turkish institutions that managed foreign and strategic affairs died with the Ottoman Empire in 1922. That’s a long time to be out of the game. Since starting to wake up from their century-long slumber a few years ago, the Turks have made some horrid mistakes:

- A botched attempt to patch things up with Armenia handed the Caucasus lock, stock, and barrel to the Russians.

- Thinking they could crack open the Palestinian issue, the Turks instead managed to rupture relations not only with the Israelis, but with nearly all the Arab states.

- Efforts to manipulate the Syrian Civil War instead slimmed relations with the Americans and led to international embarrassment by the Russians, Iranians, and Saudis.

- Turkish use of the refugee crisis as a cudgel to force concessions out of the European Union soured relations with all Europeans at all levels.

In all cases, the Turks made a typical freshman mistake. They assumed everyone would do everything the Turks said, simply because the Turks are so awesome. Such narcissistic self-aggrandizement is a natural outcome of only recently settling upon an ethnic identity after not having deep conversation with anyone on the outside for a century.

Emerging into the heart of the region is the Turkish Question: No one alive has any experience in a world in which the Turks are outward looking. No one knows how Turkey defines its interests, and so no one has a clue as to how Turkey will prioritize.

The Turks included.