The Politics of Self-Destruction

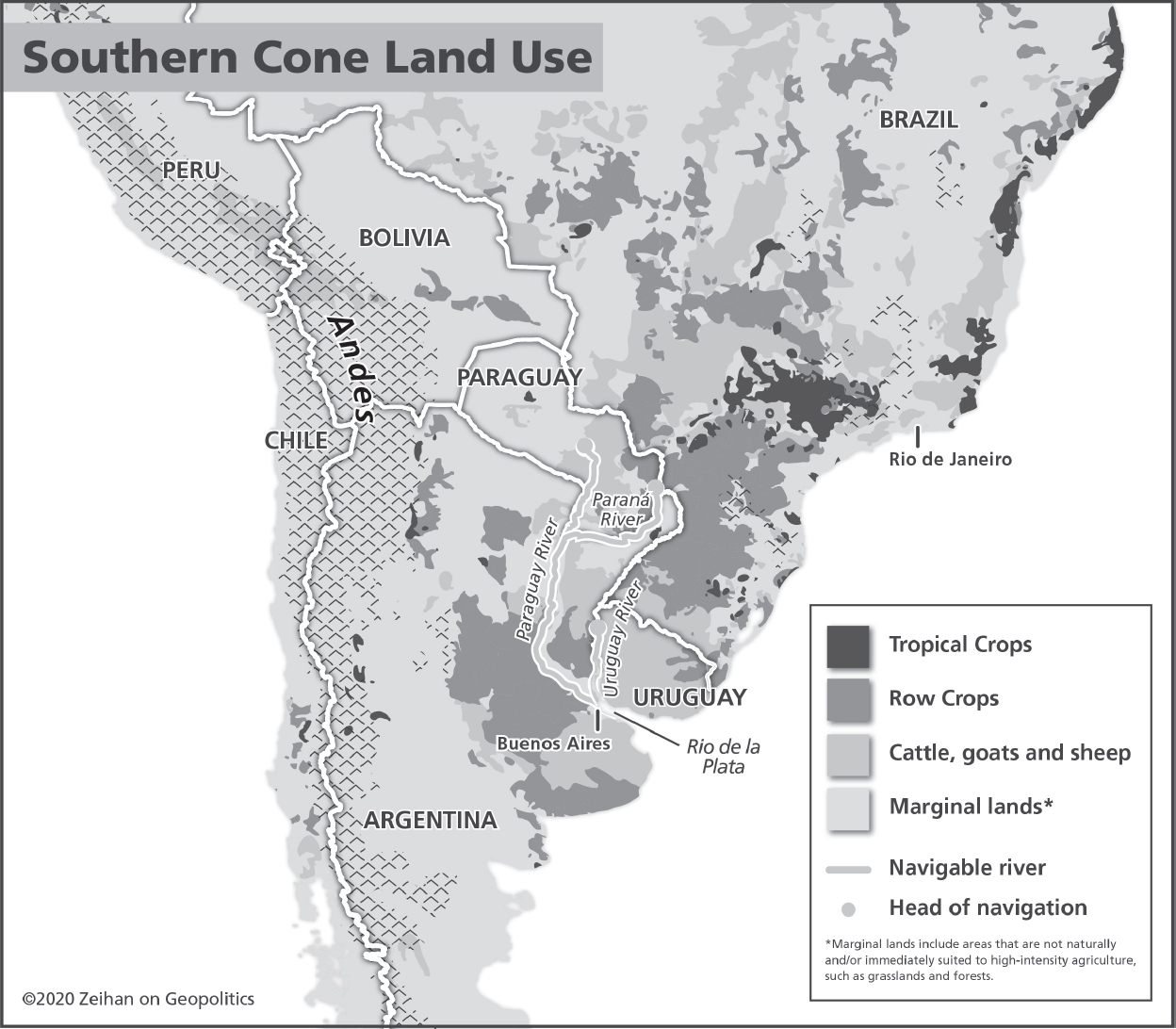

Argentina’s defining geographic feature is also the bedrock of its success. A series of South American rivers meet and empty into the Atlantic Ocean one-third of the way down Argentina’s Atlantic coastline. This confluence of rivers, named the Rio de la Plata, is one of the largest estuaries in the world and is a massive commercial hub. The three rivers that merge into it are themselves navigable: the Uruguay, Paraguay, and Paraná Rivers snake deep into the country’s northern reaches, including through most of the populated parts.

The rivers’ placement is nearly ideal, directly overlying the Pampas region—the world’s fourth-largest contiguous chunk of arable, temperate-zone agricultural land and one of the world’s most naturally fertile. At first the Paraná and Uruguay Rivers bracket a slice of territory that is among the world’s most productive rangelands. Territory to the rivers’ west is particularly good for corn and soy. To the south, the land dries out and becomes perfect for wheat. The entire Pampas is far enough south of the equator that it sees actual winter, unlike most of the countries farther north in South America. The winter insect kills are sufficient to keep pests under control, drastically improving public health and agricultural productivity without the need for scads of medications and pesticides and herbicides. The Pampas is the Midwest of South America.

But that’s where the similarity ends, for this region is not tacked on to other zones that are part of Argentina. This is Argentina.

At the very center of this entire system—in the middle of the agricultural lands and at the head of the Rio de la Plata, where all those rivers discharge—lies the gleaming city of Buenos Aires, one of the greatest metropolitan regions in the New World. Buenos Aires serves as the central node for all the country’s agricultural processing and export, all its financial and import activity, most of its industrial base, and its population core, cultural heart, and political center. It is New Orleans, Chicago, Los Angeles, Houston, Detroit, Minneapolis, New York City, San Francisco, and Washington DC all in one.

The world has many primacy cities—places where countries concentrate the bulk of their economic, political, cultural, and military power to ensure the dominant culture’s preeminence in all things. Paris, Moscow, Tokyo, Beijing, and London are quintessential examples, and in those cases, the choice was starkly deliberate. France, Russia, Japan, China, and the United Kingdom all have outland territories sufficiently rugged or distant to house restive minorities. And even after a millennium of consolidation (and ethnic cleansing), groups like the Basques, Catalans, Chechens, Ukrainians, Ainu, Tibetans, Uighurs, Cantonese, Scots, and Welsh regularly vex the French, Russians, Japanese, Han Chinese, and English. For France, Russia, Japan, China, and the United Kingdom, establishing their capitals as primacy cities was, and remains, a requirement of consolidation—a means of securing national identity in a heterogeneous milieu of geographies and ethnicities.

Not so for the Argentines. Buenos Aires isn’t simply a primacy city. It’s a naturally occurring one. Deep indentations in the country’s coastline—again that Plata estuary—make it not only the country’s best port but also place the city in the middle of the Pampas. All the core Argentine territories lie within five hundred miles of the capital. Cargo shipments within the core have little choice but to originate or terminate in the capital, and there are no geographic barriers whatsoever within that core zone. Everything naturally gravitates to Buenos Aires, no social engineering required. Many non–Buenos Aires Argentines may resent their capital’s control over their economic, political, financial, and social lives, but it is damned hard to resist the city’s centralizing pull.

The country’s omnipresent plains and plentiful rivers make it easy for the state to project power, and grants would-be rebels nowhere to hide.

External challenges are barely different. Just as it has proven simple for the Argentines to consolidate rule over Argentina, once one moves away from the Argentine core, shifts in the broader region’s climate, soil makeup, and geography make protecting the Argentine territories child’s play.

A meaningful amphibious assault is functionally impossible. Both Miami and London are nearly a seven-thousand-mile sail. Even Africa is five thousand miles away. Nor is the Southern Cone on the way to anywhere. European sails to India and the Orient are a cool six thousand miles shorter using Suez or sailing around the Cape of Good Hope. American East Coast trade with Asia would rather transit Panama. The Southern Cone is the most remote populated location on Earth.

Back on land, to the west of the Argentine core towers the meridional section of the Southern Andes, steep-sloped granite peaks so far south of the equator and so high that most boast permanent snowcap. Few passes thread these mountains at all, and winter snows and avalanches typically seal off all but four of those. The barrier is so extreme that despite sharing the continent’s longest border—and the world’s third-longest—Argentina and Chile might as well be on different planets.

To the northwest of the Argentine core lies the Gran Chaco, a grab bag of generally crappy geographies—blazing hot summers, low rainfall, erratic fertility, thorny scrubs, and the occasional swamp. While not technically barrens, most portions of this climatic region are far more trouble than they are worth and have witnessed development only in fits and starts. Most of the territory is so useless that even the nationalist-minded early Argentines had little issue ceding much of the Gran Chaco to the bitter, politically riven, largely powerless rump state of Bolivia. Other (slightly less useless) pieces serve as the western lobe of Paraguay. The better bits of Gran Chaco make up much of Argentina’s northwest frontier.

To the north lie the only land borders that might generate a bit of strategic heartburn, yet even these aren’t exactly invasion routes.

Directly north of Buenos Aires, Argentina’s core territories sink suddenly into the Iberá Wetlands, a marshy zone that blocks the most direct overland route between the Argentine core and the arable, eastern half of Paraguay. To the northeast, the Uruguay River is navigable only as far north as Concordia. Beyond that point, it is packed with rapids that complicate any meaningful crossing and end any possible routes for shipping. The mighty Paraná is traversable for a considerably longer distance, but even that abruptly stops at Guaíra, the world’s largest waterfall by volume—roughly nine times the flow of Niagara. Or at least it did. In the twentieth century, Guaíra was drowned by the creation of the Itaipu Dam, creating the world’s largest hydropower scheme. In essence, Argentina’s northern border has shifted from being damn-near impossible to penetrate to completely impassable.

That leaves the possibility, however remote, of a land invasion that is capable of crossing Argentina’s two remaining—and fairly narrow—frontiers: land approaches that follow the shores of the Paraná and Paraguay Rivers from the country of Paraguay, and across the Uruguay River from Uruguay.

The struggle over these approaches is the story of modern Argentina.

INDEPENDENCE AND THE SHAPE OF THINGS TO COME

The British colonial experience in the New World was starkly different from that of the other imperial powers, most notably from Spain’s.

The eastern coast of North America boasts barrier island chains and the Chesapeake, features that provide a plethora of coastal purchase and shielding for communities while still enabling direct sea access for all. Even inland urban zones like Philadelphia could reach the ocean via the Delaware River, while even the poorest farmer could access the maritime network to sell grain downriver. Infrastructure needs were minimal, so the need for a government was minimal. As such the American colonies were characterized by lots of smallish cities and great swathes of rural development that incrementally pushed back the frontier line.

In contrast, most of the Mexican and South American coasts were not temperate while quickly giving way to uplifts, denying both easy coastal access and internal transport options. Artificial infrastructure was an absolute necessity, and locations without it tended to be empty. Economic activity and political power concentrated in a handful of zones centered upon major cities. Such concentrations were easy to control. While the Americans right from the start became used to living and working and thriving in a world separate from—or, at most, parallel to—the government, Spanish settlers found themselves under the thumb of individuals dispatched by the imperial center in Madrid, the viceroys. These agents of the crown expressly enjoyed maximum latitude to manage the New World as they saw fit so long as they maximized revenues for Madrid. Trade with foreign countries was expressly criminalized.

Different geographic and economic features necessitated a different sort of immigrant. In proto- and early America, the limiting factor wasn’t transport or capital, but labor. A horde of hale and hearty immigrants with can-do attitudes (plus a sprinkling of criminals who were not allowed to return to Britain, backed by a far from insignificant number of slaves) fit the bill perfectly. In contrast, the Spanish New World desperately needed capital, and so attracted a cut above: the wealthy, especially those willing to relocate for a shiny new business opportunity. They’d make the trip in style, bring a bevy of peasants with them, enslave the local natives with the viceroys’ blessings, set up company towns, and get on with the business of getting richer. They were also (much) pickier about the specific spots they would settle in. While American smallholders came predominantly from poor stock and would take whatever tiny parcel of land they might be able to call their own, Spanish settlers only wanted the really good lands. They would set up the equivalent of company towns encircled by mines and farms adrift in large swathes of wilderness. Smallholders of the American style were largely unheard of; there is no Spanish version of Little House on the Prairie.

The difference made Spanish America nearly empty. By the time the newly independent American government was firmly established in 1790, the young nation held four million people to the Spanish system’s seventeen million, but those Spanish colonies occupied ten times the land area and had been founded two hundred years earlier.

The Rio de la Plata region was more different still, with much of the variation boiling down to isolation.

The range from the southern reaches of the Spanish New World colonies near Buenos Aires to the northern reaches at Santa Fe is a cool six thousand miles as the crow flies—over twice the distance from Madrid to Moscow. The functional distance was much farther than it sounds. Columbus’s first landing in the Americas was in the Caribbean, and the Spanish crown went with what it knew. Contemporary Cuba, Mexico, and eastern Colombia were the original Spanish colonies. Then Spanish penetration stalled. South of contemporary Panama and Venezuela there just weren’t many opportunities. On the Pacific, the mountainous jungle coast gave way to mountainous desert coast. On the Atlantic, the Portuguese snagged the Brazilian territories. Chewing through or skipping over all the hostile lands took a couple centuries. The rest of the colonized Americas literally had generations of development under their collective belts before the Rio de la Plata region received its first formal viceroy in 1776.

The result was a mix. In a way, the top-down, viceroy-commands-all political system of the rest of Spanish America concentrated power even more in the Rio de la Plata. Most of the best lands were in the interior, in particular the Pampas and lands extending north through what is today eastern Paraguay and edging into parts of southern Brazil and southeastern Bolivia, a zone slightly larger than the US states of North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Minnesota, and Iowa combined. In controlling Buenos Aires, the viceroy commanded it all.

And in a way the boundless horizons and labor dearth of the American model was even more applicable. The region’s singular access point combined with its navigable rivers combined with its late opening meant the entire region was thrown open to settlement at once. Add in the fact that by the time the Argentine lands started settlement the Spanish crown had outlawed native enslavement and chronic labor shortages were the norm. Robust capital plus free (high-quality) land plus massive labor shortages meant that none of the rich settlers wanted to farm—ranching was the way to go, with the wealthy settlers finding themselves toiling right alongside their gauchos.

All the output had no choice but to sail down to Buenos Aires to be processed for export. Merchants there loved that a third of a continent’s worth of bounty was a captive flow, while simultaneously viewing the viceroy’s dictates that all output was to be shipped exclusively to Spain as profoundly irritating. Yet even here the labor shortage shaped outcomes. As late as the American Revolution, Buenos Aires had but twenty-five thousand residents, making it damnably difficult for the viceroy to provide sufficient customs staff. Smuggling ran rampant.

Both in town and in the country a hybrid mind-set evolved that combined the arrogance, entitlement, and connections of old money with the sweat, pride, and ferocity of new money. It was this rural-urban split-class of old-new rich that started rebelling against the Spanish crown in the early 1800s.

Whether the Spanish crown could have maintained control of its Western Hemisphere colonies is an open question, but in the end, the future of Spanish America was decided by military developments in Old Spain. In 1803 the Napoleonic Wars began in Europe. In those wars’ many twists and turns, Spain shifted from neutral to ally of France to occupied by France. Before it was over, Spain itself imploded politically, consigning the former imperial center to political instability, economic breakdowns, and foreign invasion.

Without a functional government at the imperial center and with uprisings throughout Spanish America, the New World viceroy system shattered. Rebellions flared everywhere based on the timing and fervor of local issues. The Buenos Aires uprising took shape in May 1810, ending the city’s role as the regional seat of Spanish power. The settlers and especially second-generation merchants who were born in the New World began overturning what remained of Spanish control in favor of their own local interests. Formal separation was declared in 1816, and save a couple islands, all of Spanish America had shrugged off Spanish control by 1825.

While technically this separation meant independence, it wasn’t “Argentina” that jettisoned Imperial Spain in 1816, but rather the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata—less a country than an ad hoc council of local bigwigs. It disintegrated quickly. In part due to infighting. In part due to opposition from the wealthy settlers in the interior. In part because of the rise of a new class of elite: men who could rally the region’s scarce labor with populist calls, men who could then press guns into hands and overnight raise a militia stronger than that of a viceroy, men who could seize control of large swathes of land and set themselves up as kings. Once stirred into the mix, these caudillos ensured Argentina’s opening decades would be brutal and bloody. Some refer to this period of Argentine history as a civil war (and this period of South American history as a series of civil wars), but doing so implies that there were conflicting visions for Argentina at play. It was a great deal messier than that, because there wasn’t an Argentina.

Each caudillo and each of the remaining crop of original landholders ran his own government in his own town with his own populist patronage network based on his own personality and economic interests, and saw no reason to cede any of the political or economic authority he had created to others—most certainly not to some cocky dudes in Buenos Aires who thought they could simply step into the viceroy’s shoes. The result was a region of fractured to nonexistent loyalties, generating a system that was more or less all against all.

A mere month after the independence declaration, the fighting began. Imperial Portugal tried to mop up the formerly Spanish lands, particularly the Cisplatine, a territory that includes the contemporary country of Uruguay as well as the Brazilian province of Rio Grande do Sul. Loose coalitions of caudillos tried to fight them off, but each caudillo was interested only in his own lands. Earnestness was hard to come by; betrayals, less so.

Brazilian independence arrived in 1822. Now the Portuguese were not only trying to supplant the Spanish, but also fighting their own colonials. In the chaos of that transition, many Spanish caudillos saw an opportunity to take it all. In 1825 a broad caudillo alliance launched the Cisplatine War, crossing the Uruguay River and wreaking so much havoc that Brazil was forced to abandon the southern Cisplatine. At the war’s conclusion, in 1828, Uruguay was carved out of Brazilian territory to become an independent nation.

Then everything went to hell. The weak coalitions that held together the newly independent Argentines, Brazilians, and Uruguayans all collapsed in one way or another.

Considering the Darwinian melee of the region’s politics at the time, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the resulting Uruguayan civil war quickly sucked in various caudillos of all flavors, first indirectly, and in time with troop commitments, leading to the messy Platine War in 1851. It should further come as no surprise that the war wasn’t simply “Argentina” against “Brazil,” but Argentine caudillos against their Brazilian equivalents as well as internecine fighting and strongmen from either side courting and fighting with peers from the country opposite. National authorities not only couldn’t rein in their regions; they couldn’t even field forces. The war ended as inconclusively as it had been fought. Such developments repeatedly and starkly showcased Argentina’s (and Brazil’s and Uruguay’s) general political, military, and strategic disarray. Simply achieving meaningful armistices to the various Argentine, Brazilian, and Argentine-Brazilian conflicts generated a booming industry in conflict mediation.

Sinking in such quicksand of internecine conflict was more than self-destructive; it nearly ended Argentina and Brazil and Uruguay before they could establish themselves as countries. For there was one caudillo whose “company town” was a country, and as the big fish in the pond, he nearly ended it all.

SCARED STRAIGHT

Francisco Solano López of Paraguay was a strange cat in that he hadn’t lived his entire life in South America. In López’s younger days, his family dispatched him to Europe as an ambassador, where he had a front row seat for one of the greatest military conflicts of his generation: the Crimean War of 1853–56. In that conflict the French and British used the first generation of industrial weapons for the first time. Breech-loading rifles and ironclads and naval shells combined with railroads and the telegraph. It made for an awe-inspiring example of the world as it was about to be . . . and it couldn’t have been more different from what López had experienced back home. By the time of Spain’s fall, the Spanish were Europe’s technological laggards by a century. Spain’s colonies were a century behind that.

No more. Upon López’s return to Paraguay in 1855, he immediately launched a modernization campaign. In a mere decade “tiny, poor, backwards, landlocked” Paraguay wasn’t simply the most technically advanced country on the continent; it boasted an army over double that of Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay combined despite having a population that was less than one-twentieth its rivals’ size. A hot peace was as stable as the Plata region had been for the past half century. Conflict was inevitable. The Paraguayan War began in October 1864.

It was all about transport. Paraguay needed to deny its foes their river transport capacity, and that meant capturing Buenos Aires. Unfortunately for Paraguay, the Brazilians sank Paraguay’s only fleet at the Battle of the Riachuelo, stalling Paraguay’s initial assault while freeing the Triple Alliance of Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay to use the region’s rivers as a troop shuttle system. Five grueling years later, Paraguay wasn’t so much overrun as destroyed. Over half the country’s prewar population lay dead.

History is written by the winners, and most Latin American historians record López as unstable, maniacal, narcissistic, and vengeful. This (and more) is almost certainly true, but it misses the real points of this little side trip through history.

First, Paraguay and López didn’t just die fighting; they died fighting well. Despite the fact that the Triple Alliance picked the time and place of nearly every battle after Riachuelo, the Paraguayans gave far more than they took; in one particularly nasty battle the casualty ratio was in excess of twenty to one in Paraguay’s favor. López’s forces delivered painful lessons as to how deadly a unified, professionalized, industrialized military boasting a telegraph communication network and a railed transport system could be versus a fractured, ad hoc, musket force.

Second, the conflict bankrupted Brazil while empowering the Brazilian army at the expense of the civilian government, setting the stage for a long progression of coups, countercoups, military takeovers, debt binges, and economic collapses that has defined and hobbled the country ever since.

Third, power was also centralized in Argentina but with different implications. A few months into the war, the Argentine elite realized just how narrowly they had escaped mutual eradication. They threw everything they had at Paraguay. The war necessitated the centralization of the country’s military, economic, and political life under Buenos Aires. It took the death-scare of upstart Paraguay to forge Argentines into a nation. And in a textbook example of geography’s influence, in Argentina it took.

Within months of victory over Paraguay, the Argentines turned their newly formed military south, culminating in the “Conquest of the Desert” to eliminate the indigenous tribes living between the Negro River and the mythic mountains of Patagonia. The Conquest featured the same genocidal features of America’s Indian Wars: one-sided battles, the killing of unarmed civilians, land rushes, ethnic cleansing, forced marches, and the intentional spread of diseases. But here it happened with the best military technologies the early industrial era had to offer, and so it was all over in a decade. Repeating rifles versus clubs tends to compress the time frame. The result was as final as it was predictable: the writ of newly empowered Buenos Aires became firmly and permanently entrenched throughout the territories we now know as Argentina.

SUPERPOWER, INTERRUPTED

With the wars over, the Argentine government got busy doing the things governments do: establishing a continuity, forging a mass educational system, threading infrastructure throughout the territories. All along the way, mighty Buenos Aires easily absorbed all the commerce and dynamism the young country could produce, yet a mixture of past and future ultimately sent the place off the rails.

First, the past. While achieving economies of scale in Argentina was soooo eeeeasy, things still needed to be built, and that took money. A torrent of primarily late-Imperial British money helped bring the country’s natural agricultural advantages into full bloom. But that foreign money wasn’t lent to just anyone, only to men who had economic and political track records worth trusting—only to the regional oligarchs who had inherited their mantles from the original (rich) settlers and merchants and, more recently, the caudillos. By the headline figures, Argentina may have been doing well, but wealth inequality ran as wild as wealth, and the debt overhang was truly massive. When Britain found itself in need of cash to fight the First World War, the Brits called for repayment, triggering Argentina’s first financial collapse.

Second, the future. Argentina wasn’t the Western Hemisphere’s only big chunk of arable land shot through with navigable waterways. For the first 125 years of the United States’ history, the Americans mostly kept their nose in their home continent. But part and parcel of the post–Civil War Reconstruction effort was to knit the country back together with the latest in industrialized infrastructure. When the Americans had their coming-out party in the 1890s, their historically unprecedented economies of scale took global agricultural markets by storm. Argentina may have had great lands and great rivers, but America’s were even better. And unlike the United States of the Order era, pre–World Wars America was downright mercantilist and not about to cede market share to anyone.

To compensate, the Argentine state waded into agricultural markets with borrowed funds, subsidizing the oligarchs’ enterprises. Social inequality and economic desperation of the lower classes boiled over just before the Great Depression hit. To prevent anarchy, the military launched a coup in 1930, setting off decades of juntas, coups, and populist uprisings.

Crystalizing the patterns of chaos and dysfunction among plenty, which defines Argentina to the current day, was the leadership of one Juan Domingo Perón, a populist who ascended to the presidency in 1946.

Perón’s cult of personality is a study in contradictions. Peronism views the state as the ultimate guarantor of worker’s rights, but also dissolves unions and criminalizes workers’ right to protest while lobbying on their behalf . . . to factory managers the government commands. It makes the government the primary mover of the economy but uses a communist-cum-fascist approach to public and private ownership of the means of production.

Under Peronism and oftentimes violent bouts of anti-Peronism, Argentina lost almost everything. Once a leading power in wheat, corn, pork, beef, oil, and natural gas markets, Argentina nearly became an importer of all of them. Once the undisputed second power of the Western Hemisphere, Argentina is barely even relevant within its own region. All in all, pretty much everything that made the Argentines rich, sophisticated, and powerful has bled away.

Yet even suffering from a history of politicians who were, shall we say, unique in their deliberate incompetence, Argentina is set up phenomenally well for the Disorder to come.

First, Argentina is beyond the back of beyond. While in the contemporary era of nuclear-powered aircraft carriers the Southern Cone isn’t nearly as isolated as it was in the sail era, it is still a long trip to Buenos Aires from the Eastern Hemisphere. America’s de facto enforcement of the Monroe Doctrine will keep any would-be predators out of South America. Add Brazil’s general discombobulation, and there are no countries on the planet except New Zealand with as good a physical security position as Argentina.

Second and somewhat ironically, despite Argentine safety, the country remains packed with everything the wider world needs.

Part of this is obvious: despite the recent ravages of Peronist governments in the 2000s and 2010s, the country’s export potential for any number of temperate-zone agricultural products remains massive. It wouldn’t take a very forward-looking government policy to upgrade Argentine output to the point the country could storm into the world’s top ten list of producers or exporters of corn, soy, wheat, poultry, and beef.

Part of the Argentine bounty is less obvious. Argentina sports significant shale petroleum reserves. While shale deposits are fairly common globally, most of the world’s are not all that useful. Most are thin and petroleum-poor, and located inconveniently far from population centers. Not so in Argentina.

Here they rival those in North America: petroleum-dense and proximate to preexisting oil transport infrastructure already linked to major metropolitan regions.

Bringing such fields online would take a few years instead of a few decades. Argentina’s coming shale boom (probably) won’t be as transformative as the United States’, but it will still be large enough to make Argentina a significant exporter of natural gas and oil—just as it was in the mid-twentieth century. Argentina already boasts the world’s third-largest shale oil and natural gas production, behind only the United States and Canada. As an additional kicker, Argentina is coolly in the top five countries globally for solar and wind potential. Every electron green power can generate locally is another bit of petroleum available for export.

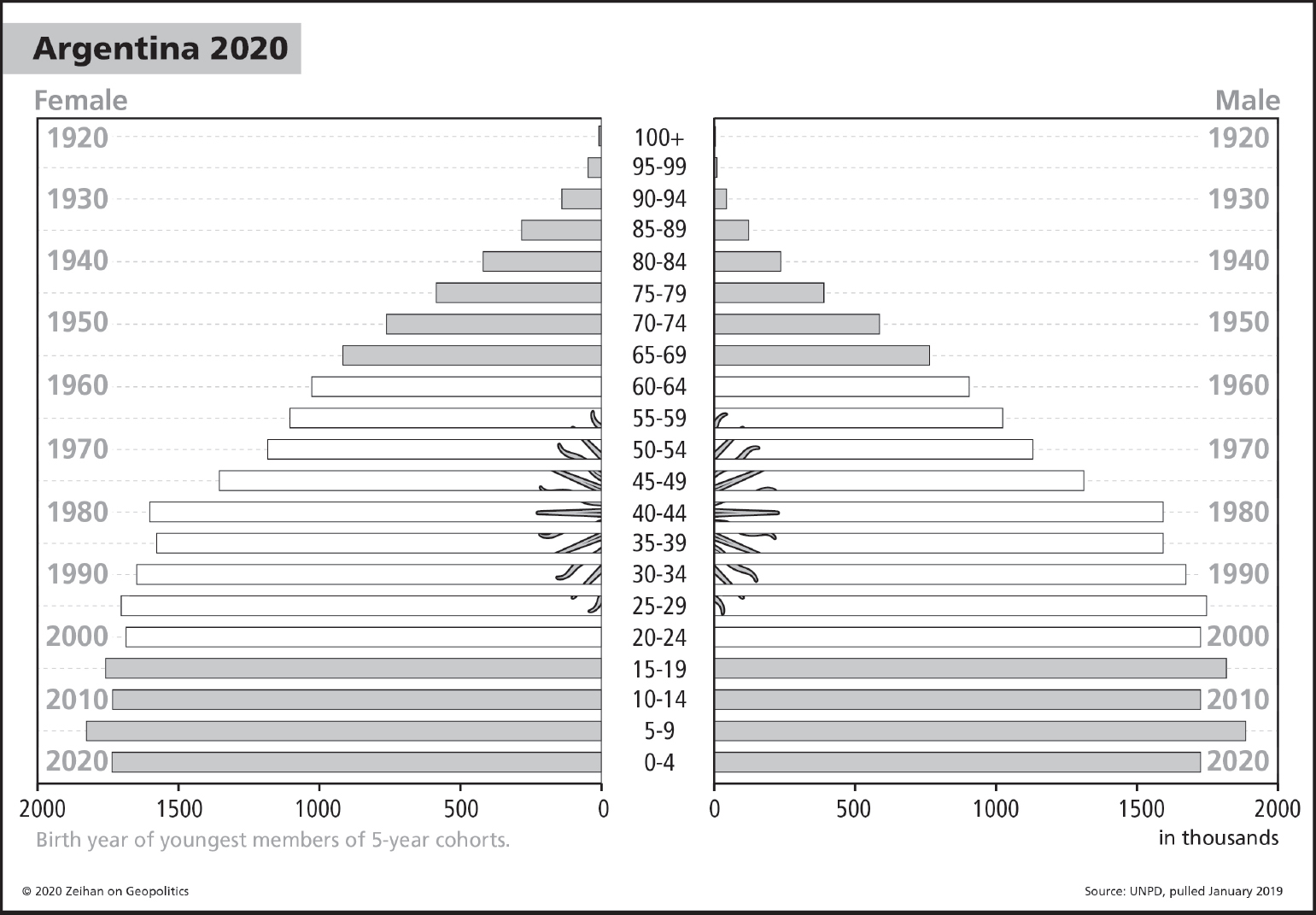

Even better—and rarer—Argentina’s population structure is sublime for a country at its stage of development.

In part, this is an inadvertent legacy of Peronism. One of Peronism’s most pernicious impacts is its subsidization of basic goods. Lower prices for food and electricity encourages the population to use more than they would normally. At first, the government has to pay for the difference, but once the government runs out of money and maxes out its ability to borrow, the cost is passed on to producers. Faced with government price caps that are below the cost of production, most producers do what comes naturally: they stop producing. The result is massive state debt, huge distortions in supply and demand, endemic corruption, resource mismanagement on an epic scale, a collapse of the productive sector, and goods shortages in pretty much everything. Argentina has lived through this cycle several times already.

However, one perk of the Peronist style of subsidization is that cheap food, housing, electricity, and water mitigate the cost of raising children in an urban environment. Argentina boasts a preindustrial population structure with the skilled labor set of an industrial society. Such a huge proportion of skilled labor compared with the overall population puts Argentina at the opposite end of the scale from Brazil. Even in worst-case circumstances, the Argentines are both young enough and aging slowly enough that they will not face an American-style—much less a European-style—retiree budget pinch until 2070 at the earliest. For comparison, the Brazilians—crammed as they are into tiny urban plots—will hit that point by 2045 at the latest.

In a world degrading into energy shortages, physical insecurity, and demographic collapses, Argentina boasts the resources, land, rivers, geographic position, and demographic structure to make the most of an age of Disorder.

There is even a tantalizing possibility that Argentina could develop a South American echo of East Asian manufacturing. It has a similar labor-market structure and the kind of physical and energy security that underpinned the 1970–90 Asia boom. Even better, with the sole exception of the United States, no country has enjoyed such domestically powered consumption-led growth since before the global baby bust of the 1980s. “All” Argentina needs is some raw materials access (which it can source from Brazil), some imported capital (likely from the United States), and a better legal and regulatory environment (which is entirely up to the Argentines).

It all adds up to make Argentina a bit like Turkey, but without the external security complications. With the Peronist rise, Argentines, for the most part, have alternatively wallowed in narcissistic populism or domestic reactions to Peronism. They’ve gone from being globally significant in the 1880s through the 1920s to barely being even regionally relevant today.

But with the world falling into a deglobalization death spiral, one of two things is going to happen.

In option one, the Argentines elect governments that unwind many of the crippling impacts of Peronism. In such a circumstance, Argentina’s underlying features shine through, and it becomes a continental—a global—success story in a decade or two.

In option two, Peronism persists, and the Argentine economy remains statist and inefficient and self-destructive. Investment would lag, and general degradation would be the order of the day. But even then Argentina has a near-perfect demographic profile, which is rare. It has resource wealth, which is rare. It has dreamy geography, exceedingly rare. Most of all, the Argentines simply have a lot more hands-on experience operating in a world ruled by dysfunction and populism and conflict than anyone else. Argentina might not shine, but it will still look better than nearly every other country in the world.

Regardless of whether the Argentines move to the middle or the middle moves to Argentina, Argentina’s superior geography and demographic structure ensure its success moving forward. Argentina’s impending golden age is only an issue of degree.

DEFINING SUCCESS

Organizationally, economically, politically, and diplomatically, Argentina is starting from century lows. The ravages of Peronism and anti-Peronism have wrecked much of the country’s capacity for even thinking about the outside world. Even if Buenos Aires came up with a deviously brilliant master plan today and executed it competently and faithfully, the cultural hole the country is in is so deep that Argentina would not become a force in global affairs beyond its product sales within two decades.

Instead, regardless of intent, Argentina will become the natural centerweight of its region. Geographic patterns make it obvious how it will all progress.

Step one: just as the rivers gave the Triple Alliance the ability to smack down López in the Paraguayan War, they remain the key to controlling Argentina’s neighbors. During the Peronist implosion of the 2000s, the Argentine system weakened so much that local authorities stopped dredging the shipping channels of the Uruguay, Paraguay, and Paraná Rivers. During the same period, a perfectly timed burst of infrastructure policy in Brazil enabled Paraguayan agricultural producers to send their output through Brazil via truck to the wider world. Brazilian roads are wildly more expensive than Argentine river ports, but Argentina proved itself so unreliable, the exporters had no choice. Consequently, Brazil is now far and away the dominant economic power in both countries.

All Argentina needs to do to ensure that these countries fall back into its orbit is keep its rivers’ shipping channels functioning, something already in the Argentines’ domestic self-interest. Basic economics will see to the rest.

But more than trade-related income is the strategic value of Uruguay. Its capital of Montevideo sits almost directly opposite Buenos Aires on the Rio de la Plata. If anyone ever were to wish Argentina ill, Montevideo would be the launching point. Control of the city threatens outbound Argentine shipping, giving Montevideo effective command of both the Argentine capital and the entire Argentine core. The Argentines are not used to thinking strategically, but as the world shifts and an older sort of thinking creeps back, they will recall their battles with the Spanish, the British, the Portuguese, and the Brazilians over just this scrap of land.

Step two involves Argentina’s other pair of border states—Bolivia and Chile—and requires slightly more thinking.

Chile is a schizophrenic place, split between a single valley system packed with farms, orchards, and vineyards in the country’s middle, and tenuously linked to a series of copper and lithium mines in the country’s northern deserts. Such an odd setup has only persevered for three reasons.

First, the Andes prevents significant interaction with Argentina. Weak Argentina or strong Argentina, the Andes will always limit contact, helping preserve this Chilean geographic oddity.

Second, the only country with sufficient exposure and interest to challenge Chile is Bolivia, and Bolivia is just as split as Chile. Two-thirds of the population (largely natives) lives in the highlands, while two-thirds of the economy (largely agricultural) is generated from farms in the lowlands that abut Brazil.

Way back in the War of the Pacific of 1879–84 the Bolivians and Chileans crossed swords. As part of the postwar settlements, the Bolivians had to surrender to Chile all their ocean frontage as well as much of the Atacama Desert—the same desert that is home to most of contemporary Chile’s copper and lithium production. Bolivia remains just as pissed off at Chile now as it was when it lost the war over a century ago.

The feud gives Argentina a wealth of opportunities. Argentina used to provide Chile with natural gas, but Argentina’s 2000s collapse pretty much ended that. More recently, natural gas production and exports are again trending upward. Recovery in other sectors will naturally make Argentina Chile’s primary supplier for most everything food- and energy-related. For its part, Bolivia refuses to ship its exports to the wider world via Chile, so when Argentina was in its 2000s Peronist funk, Bolivian mine output from the highlands made the long, arduous trip through the Chaco and Brazilian territory to the Atlantic Ocean. Very light tweaks to Argentine policy would make transport much easier. The Chilean capital of Santiago isn’t even all that far from Argentina’s world-class solar and wind potential. Argentina can expand its economic footprint in both countries while also becoming essential for both countries’ expanded economic interaction with each other.

That just leaves Brazil.

Much like Argentine relations with Uruguay and Paraguay, the shifting balance with Brazil does not require much planning or a particularly heavy hand. It doesn’t take a policy of infiltration out of Buenos Aires to translate economic growth in Argentina to greater influence over the Brazilian border regions. The Paraná River is navigable all the way up into central Paraguay. It would be far easier and cheaper for Brazilian farmers in the province of Mato Grosso do Sul to ship their output to Asunción for loading onto Buenos Aires–bound barges than to truck it up and over Brazil’s Grand Escarpment.

To put it simply, Argentina’s geographic features condemn it to being a successful country, while Brazil’s features restrict it to being successful only in very specific circumstances that are both beyond its control and no longer extant. Brazil’s fall enables Argentina to passively leach into becoming something more. It adds up to a different sort of Southern Cone, with Argentina not simply eclipsing Brazil as the dominant regional power but putting the best territories of the South American continent all within a single sphere of influence.

For those who find all things South American a bit of a yawner, consider this: if Argentina succeeds in reconsolidating its own nation and achieving primacy in Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay, then Argentina will command the world’s fourth-largest chunk of temperate-zone arable land via the world’s second-largest naturally connected, naturally navigable waterway network in a regional geography where it has no competition. As Argentina recovers, it will quickly become a sandbox superpower, but in facing no local threats whatsoever, in time the Argentines will find it really easy to project out. It is precisely this combination of factors that in time created the American superpower.