France has been the world’s second power for a very long time.

After France’s emergence from the breakup of Charlemagne’s empire, Paris seemingly always found itself on the back foot. Versus the Arabs. The Italians. The Spanish. The English. The Germans. The Americans. With every shift in political and technological trends, France just didn’t quite measure up. When the Americans crafted a global system, freezing geopolitical competitions in place, France could only be a cog in the machine.

France never really took advantage of the economic side of the global Order. The French kept most of their production in-house, jealously protecting their statist, domestic market. The French economy barely even Europeanized. The French diplomatic network has been kept jealously separate from EU positions—except in those EU positions that have been led by France. The French military maintains a strong capacity for independent action. Under the Order, this was all massively inefficient, broadly unsuccessful, and a huge wasted opportunity.

In contrast, the contemporary German system was customized to operate within the Order’s parameters: global economies of scale, bottomless resource and market access, zero security responsibility, a heretofore unheard-of European continuity. Germany has boomed; France has stagnated.

And yet with the Order’s end, history thaws. Remove the Order and Germany will find itself either doing without all the economic features that enable it to be a multiparty social-welfare democracy, or it will be forced to fight for everything from market access to resource access, and fight some more to protect its sphere of influence and perhaps even its borders. A competition with Russia over the countries between them beckons. Potentially catastrophic? Certainly. Yet Germany’s occupation with economic decay and geostrategic competition positions France at a bay window of opportunity that has never occurred before.

For without the global Order the current French economic model is one of the few systems that will still work. Paris maintains reasonably good working relationships with the Americans, the British, the Dutch, the Spanish, the Italians, the Germans—even the Russians. French political history oozes with examples of managing and maximizing and manipulating in a shifting geopolitical environment. The mix of positioning and preparation is half of why so many European treaties are signed in Paris in the first place, and none of these factors have anything to do with what the Americans are—or are not—up to.

France is emerging as the only significant European power with a sustainable domestic system and no strategic entanglements, leaving it free to shape Europe in its own image—and perhaps do the same in lands beyond.

After a history full of coming in second, France’s hour has finally arrived.

THE POWER OF PARIS

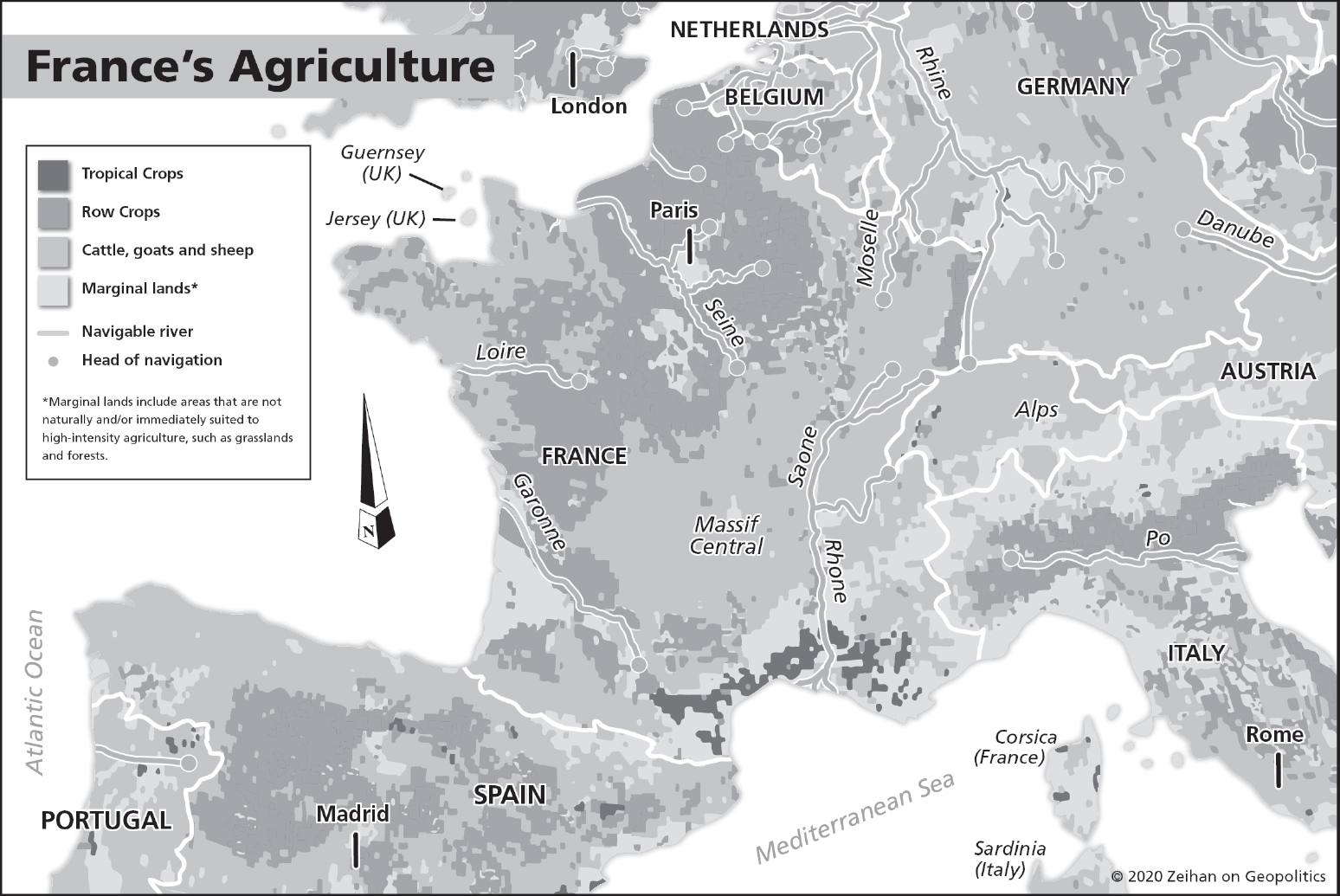

Distilled to its basic elements, France is a power due to a specific region: the Beauce. The Beauce’s limestone-rich soils place it among the world’s most fertile agricultural regions, and its surpluses have proven sufficient to feed all of northern France for centuries. But that is just the beginning. There is more—far more—to the Beauce than the inputs for Brie, butter, and baguettes.

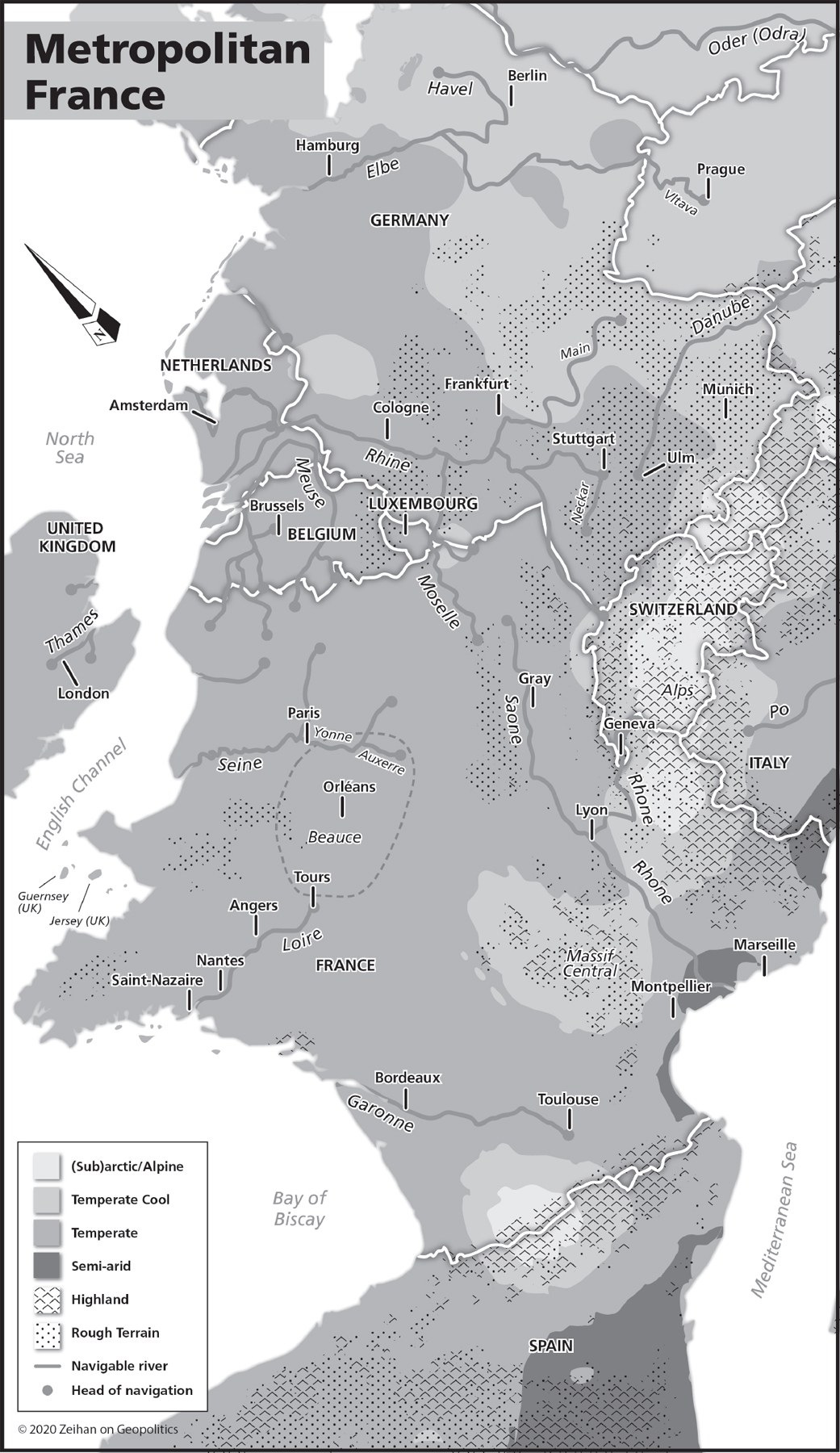

The river Yonne cuts south to north through the Beauce’s eastern half, bringing all the normal benefits of cheap transport to high-quality agricultural lands that are the recipe for success throughout the world. But the Yonne is no standard river. Some sixty-seven miles downstream of the head of navigation at Auxerre, the Yonne empties into the Seine system just above the Paris metropolitan region. The Seine system webworks about 280 miles of river frontage in France’s northern lobe, connecting the Beauce’s bounty to several population cores, including the capital.

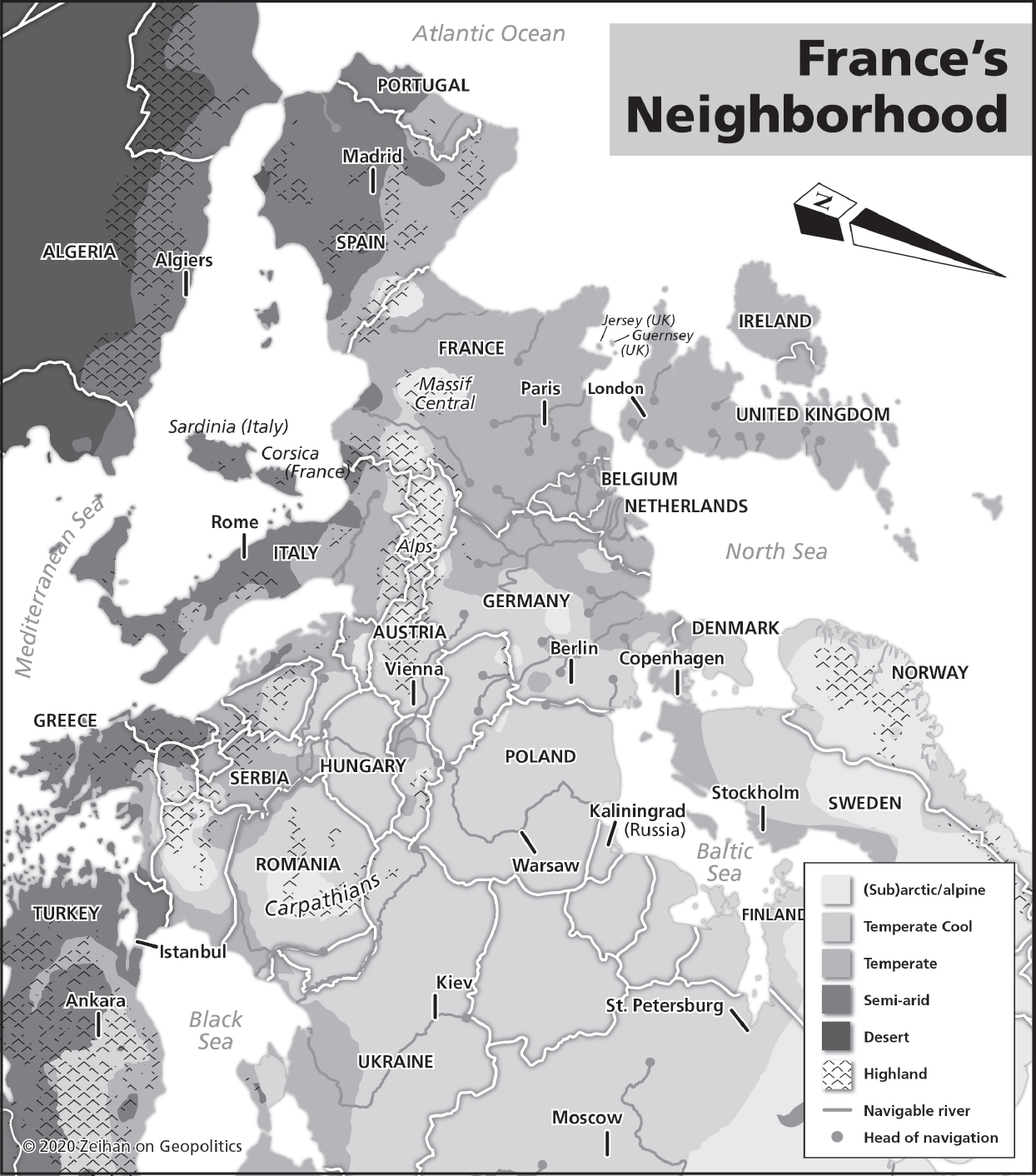

The Seine then drains into the English Channel, making France part of the hustle and bustle of the Northern European Plain. The plain is home to not just the French but also the Belgians, Dutch, Germans, Danes, Poles, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, and Belarusians before it merges seamlessly into the great wide opens of the Eurasian Hordelands, home of the Ukrainians, Russians, Kazakhs, and more. Nowhere in the world are so many different ethnicities with their own countries crammed into a single geographic feature. Paris’s location along the Seine—near the far western end of the NEP—guarantees the French a seat at any European table.

Undeniably, it is the Beauce-Seine connection that makes France a quintessential Northern European power, complete with all the wealth and capacity that appertain thereto. But as central to the French identity as Paris and the Seine are, they are not enough. Luckily the French have more. Much more.

Just as the Seine makes France a power of Northern Europe, the Rhône makes France a power of Southern Europe. But unlike the busyness of Northern Europe, there simply isn’t very much competition down south. The Mediterranean Basin’s extreme aridity limits civilizational options. There are few places where the land rises sharply enough to wring some rain out of the dry air; those locations bloom as a result, but that same sharp rise prevents local rivers from having the calm flatness required for navigability—and from that, national potency. France is the only power with Mediterranean frontage that’s an exception. Undeniably, it is the Beauce-Rhône connection that makes France a quintessential Mediterranean power, complete with all the wealth and capacity that comes with that stature.

Tickling the Beauce’s southern edges flows yet another river: the Loire, the river of kings.* While technically still a Northern European river, the Loire actually flows west, linking the cities of the French imagination—Orléans, Tours, Angers, Nantes—before ultimately emptying into the Bay of Biscay.

The flood-prone and rapids-filled Loire may no longer be commercially navigable by the somewhat exacting standards of modern containerized shipping, but it has been an artery for Parisian influence throughout French history—and not just internally. The terminal Loire port of Saint-Nazaire—even today home to France’s largest shipyards—is far removed from traditional French competitors in Scandinavia, Great Britain, and the North European Plain. In many ways the Loire Basin serves as France’s window out of the Old World, enabling it to be a player on a far larger stage than “merely” Europe.

And these aren’t even all of France’s rivers. The Meuse enables the French to dominate much of Belgium. The Moselle is a tributary of a border river—the Rhine—that enables French influence into both Germany and the Netherlands. Follow the Rhône upriver and one ends up in Switzerland, giving the French a clear path to the heart of Europe’s supposedly neutral power. The Garonne is navigable all the way upstream to Toulouse, a mere hundred miles from the Mediterranean coast, increasing French influence over countries south, while also creating a river-and-road shortcut that negates the need for the long sail around Iberia.

Even the arrangement of France’s rivers encourages her onward.

The navigable flows of the Seine and Loire are close enough together to cradle all of northwest France. Perhaps a better verb would be smother. Somewhat rugged regions, like Normandy and Brittany, would normally be too remote from the river zones to be assimilated easily and thus be likely to turn rebellious. The two rivers’ layout enables the direct injection of Parisian influence throughout both. For all intents and purposes, this makes all of northwestern France part of an enlarged core territory. The Rhône has a similar effect on the Alps and the Riviera, while the Garonne links in Bordeaux. Even France’s most rugged, upland region—the Massif Central—is not immune. The region is so steep, it received its first true multilane roadway only in the 2000s, but because it is bracketed by the Rhône to the east and the Garonne to the west, even here French cultural power eroded meaningful separatist tendencies centuries ago.

Even the shape of France, in essence a knob near the end of the European peninsula, helps. France’s frontage on the English Channel, Bay of Biscay, and the Mediterranean gives it a mild, marine climate far more typical of an island. Compared with the bulk of Europe, France is warmer and wetter, while also experiencing less extreme seasonal variations. With the exception of the highlands of the Massif Central, all of France is firmly temperate.

France even has pretty good borders. On France’s southern and southeastern borders jut the Pyrenees and Alps, both replete with peaks so sharp, they have permitted little direct land contact with the Iberian and Apennine Peninsulas throughout recorded history.

Even France’s borders on the invasion-happy corridor of the Northern European Plain are somewhat circumscribed. To France’s northeast, a series of densely forested foothills push from the Alps nearly to the North Sea coast, making this Belgian Gap the Northern European Plain’s narrowest point. Unsurprisingly, this chokepoint has been the site of some of the fiercest fighting throughout European history.*

France’s many rivers distribute the Beauce’s bounty far and wide. They serve as arteries for commercial interests. They entrench the French national identity. They encourage power projection in three wildly different directions into three wildly different regions: the Channel and North Sea, the Mediterranean and the Middle East, and the Bay of Biscay and the New World. They shelter France in the most defensible position possible on the Northern European Plain while still enabling the French to take advantage of all the opportunities the plain can provide.

And as geography doesn’t change, those opportunities have existed for a long time.

With the Roman Empire’s fall, Latin influence merged with—as opposed to overwriting or being expunged from—local norms. The result? A cohesive French identity as early as the fifth century, a full half millennium before the English and twice that before the German. From the French core in the Beauce, this identity seeped into peripheral spheres: remnant Celts in Normandy, Germanic tribes to the east, pockets of Basques in the southwest, even the isolated peoples of the Massif. The French have arguably the longest tradition of operating as a cohesive culture vis-à-vis their location of any people on Earth.

France’s unique mix of geographies does more than make it special. The configuration of French lands makes it culturally sophisticated, economically aware, technologically advanced, politically robust, and diplomatically essential. It makes France rich, whether in the sleepy countryside or the City of Light. It makes France involved in places as close as Berne and Brussels and as far away as Montreal and Saigon. It grants the French a deep understanding of how the pieces fit together and what levers need to be pulled to achieve this or that result. It makes France a superpower, and a durable one at that. . . .

. . . which is not the same as saying it has always been an easy road.

THE GEOPOLITICS OF LIMITATION, PART I: NATIONALISM

Late-eighteenth-century France was a gooey Petri dish, marinating a riotous mix of destabilizing elements. The early industrial technologies were disrupting traditional craftsmen. The printing press was granting the media huge reach, but it had not yet established standards for accuracy or a commitment to the public good.* The Catholic clergy was experiencing a rise in political influence like that of the Protestants during the Thirty Years’ War, and they were wielding it in ways both enthusiastic and inexpert. Halfhearted economic reforms contributed to food shortages. Mounting debt restricted the government’s room to maneuver. The reigning monarch—Louis XVI—was kind of a moron.

In short, the place was ready to blow. Think of the virus of American democracy upon this system as less the systemic disruptor and more the proverbial straw.

It got pretty ugly. The French Revolution didn’t simply behead the royal family. Its subsequent Terror introduced Western Civilization to populism of the ugliest sort—mobs large and small literally burning down the Ancien Régime, complete with impromptu execution tribunals so prolific that there were occasional basket shortages because so many heads needed to be caught. Things like this happen when ossified cultural, military, and economic norms melt away in a few short months.* What emerged from the detritus in the French Terror’s aftermath, however, wasn’t simply a reborn France, but something fundamentally new.

Nationalist France.

From a geopolitical point of view, nationalism’s defining characteristic is its capacity to better harness national power. Medieval feudalism splits capacity among the royals, the nobles, and the peasantry, with loyalty within and among the three largely determined by a system of bribes and threats. It works, but is wildly inefficient. In contrast, nationalism fuses ethnic identity directly to a centralized governing system, both eliminating the middleman and making loyalty part of the governing rationale. Such organizational slimming funnels more resources—financial and labor, in particular—to the one government that rules it all.

Nationalism took root quickly, in no small part because France’s rivers enabled the quick transmission of ideas. A single horrific bloodbath to annihilate the economic and political classes of the medieval order and France was off to the races.

The question quickly became what to do with all those newly concentrated resources. Nationalism suggests the answer. Because the nation-state is rooted in ethnicity, not everyone qualifies as “people.” Sitting not-so-comfortably on the other side of the twentieth century, you probably see where this is going. Nationalism might make for a much more powerful, capable, inclusive, and accountable state than feudalism, but it also makes it excruciatingly easy to march to war.

Empowered by the social technology of nationalism, France was the most consolidated, stable, mobilized, and potent country of the early 1800s. In contrast, the rest of Europe was politically shattered, emotionally demoralized, and in many cases militarily incompetent. Napoléon Bonaparte wielded the merger of ethnic and government interests against his unsuspecting foes like a flamethrower against soccer hooligans. In a few short years, France’s citizen armies had either conquered or forced alliance upon every country on the North European Plain, as well as Italy and Iberia, and stood at the gates of Moscow itself.

Yet the French bid didn’t simply fail, it failed catastrophically. Which brings us to the first lesson of French power: even when France has its ducks rowed up and everyone else has gone fishing, the geography of Europe—the endless Northern European Plain, the variety of highlands and peninsulas and islands—means France can never win.

THE GEOPOLITICS OF LIMITATION, PART II: INDUSTRIALIZATION

If nationalism gave the French a leg up on the competition, then industrialization did the same for France’s competitors.

Early nineteenth-century German lands were a cartographic mess made up of dozens of independent and often mutually antagonistic statelets immensely susceptible to the Industrial Revolution’s challenges. Chemical fertilizers reduced farm-labor requirements, impoverishing feudal lords while forcing farmers off their lands. Imported manufactures blasted away the Germans’ sophisticated guild system (i.e., the middle class of the time). The pressures built to a head with the unrest of 1848, when many of the statelets flirted with open collapse, civil war, or both.

Yet the Industrial Revolution also provided the tools to solve the Germans’ age-old problem: the disconnected nature of the German geography. The new road and rail technologies overcame the physical barriers separating the German principalities. Simultaneously, the Germans learned about nationalism’s invigorating capacities from the French.

These twin revolutions—technical and social—had the deepest impact on Prussia, the largest and most powerful of the German entities. The Prussians extended their writ by rhetoric and rail to adjoining statelets, becoming more authoritarian and aggressive with each expansion. A mere sixteen years after the revolts of 1848, Prussia absorbed several of its Germanic neighbors and defeated Denmark in a war. Two years later, it repeated the process with Austria. A mere four years after that, the Prussians came for the French.

The French were breathlessly unprepared for industrialized warfare, not simply because panache and élan are no match for rifles and artillery. Industrialized warfare is about more than simply putting new hardware in soldiers’ hands. It’s also about everything that backs an army up back home.

Industrialized medicines drastically reduced fatality rates. Industrialized agriculture and fertilizer created food surpluses, eliminating many restrictions on military planning. Famine and disease—factors that in preindustrial warfare were far more likely than bullets to kill soldiers—became more manageable. Railways reduced deployment times from months to days and allowed resupply from hundreds of miles away. The telegraph enabled military planners to adjust attacks, order retreats, reinforce besieged units, or take advantage of gaps in enemy formations within hours.

Early German victories enabled German forces to reach Paris in a mere six weeks, where they laid siege and waited for the city to starve. Germany’s new long-range cannon underlined with force the thought that any breakout attempt would merely be a very splashy way to commit suicide. When all was said and done, the French suffered five times the troop losses of the Germans.

The French found themselves similarly outclassed in both of the World Wars. Which brings us to the second lesson of French power: the interconnected nature of the European geography means other European countries need not be at their peak to defeat France.

The country that matters the most to France’s rises and falls will always be Germany.

The Germans have the power: as cool as the Beauce is, it is no bigger than the US state of Kentucky. German core lands are six times as large, while German rivers have approximately twice the capital-generation capacity of French rivers.

The Germans have the proximity: the distance from Paris to the German border is less than 250 miles, roughly the distance from DC to New York City.

The Germans have the concentration: France may be able to wield power in many places, but Germany is concerned only with the Northern European Plain.

If the Germans can unite their disparate regions, there is little the French can do in a straight-up fight but look for white sheets to cut into easy-to-wave rectangles.

Managing the German question must be France’s top priority.

FRANCE UNDER THE ORDER, PART I: IT WAS THE BEST OF TIMES

The best way to “manage” Germany is to turn the tables and ensure that Paris is firmly in charge of the relationship.

Direct occupation sounds sexy but is ultimately counterproductive. If French forces advance through the Belgian Gap, they discover there is nothing to hunker behind. The Rhine Valley bleeds into the northern German coast into the Elbe and Oder systems into the Polish Plain into the Hordelands. Napoleon didn’t march on Moscow because he liked the food; he did so because moving past Alsace requires breaking all powers that live on the plain.

Something savvier and more holistic is required. The trick is to find a way to harness Germany so France can benefit from German economic strength, while also hobbling Germany so Berlin can’t use that strength to Paris’s detriment. Such puppet-mastering requires the modification of the very environment of Europe.

It is with no small amount of French annoyance that it was the Americans who crafted that perfect alignment. With the imposition of the Bretton Woods Order, the Americans took security planning off the table completely—defanging Germany as a military power. Politically, the Americans and their British (and French!) allies imposed a new constitution upon Germany so the Germans could never threaten the Order.

This neutering was only one piece of Europe’s changed circumstances: After World War II, Portugal and Spain remained locked away in their own isolationist dictatorships. Britain was strategically exhausted and could no longer manipulate Continental events. The Iron Curtain cut Europe’s eastern third off from all consideration. The war’s victors amalgamated Serbia into a unified Yugoslavia that was neither Soviet- nor Western-aligned. The still-independent Turks were on the far side of the Soviet-occupied Balkan Peninsula and so could no longer participate in European affairs. The Finns and Swedes retreated into armed neutrality to limit the rationale for a Soviet attack.

The Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg—three countries that had been ground under the Nazi boot for a half-decade—needed whatever association was on offer to facilitate their economic and political rehabilitation. As a defeated Axis power, Italy had foreign affairs fully removed from its remit, leaving it to someone else to . . . tell it what to do. Germany wasn’t simply occupied; it was partitioned. The original German heartland between the Elbe and the Oder was carved off into the Soviet sphere of influence. The most significant bit that was still part of the west? The Rhineland, hard on France’s border.

France could not win in a European battle royale, even when the deck was stacked for it, but if what was left of Europe was only one-third the size, if the Northern European Plain was no longer an endless road, if the Germans were economically, strategically, and politically neutered . . . well, that’s a completely different sort of competition.

Facing a very different European geography, Paris got down to the nitty-gritty of crafting a French order for Europe. The result was a series of institutions to lash German power tightly to French goals: the European Coal and Steel Community, the European Atomic Energy Community, the European Economic Community—all precursors to what would in time evolve into the European Union. Technically, all were joint Franco-German efforts, but with the Americans conveniently smothering German decision making, the French didn’t feel obligated to issue Berlin an opinion.

The money was good too. The new European institutions regularly pulled funds out of the German budget, transferring them to French needs. Call it exploitation. Call it war reparations. Call it agricultural subsidies or development funds. The French called it fantastique! France’s centuries-long goal of being Europe’s first power had finally been achieved.

But it wasn’t all champagne and cheese.

FRANCE UNDER THE ORDER, PART II: IT WAS THE WORST OF TIMES

Because the new French-led European system was possible only because the Americans ran the table in World War II, the French were forced to follow the Americans’ new global lead. Yes, when it came to European political and economic affairs, the French were large and in charge, but in the military sphere as well as every facet of the global environment, the Americans dominated. France may have been on the rise in Europe, but—like all the other imperial systems—it was in screaming retreat everywhere else:

- In Vietnam local insurgents managed to gut French forces at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, collapsing the government back in Paris and forcing a French withdrawal from Indochina.

- When the Algerian Revolution began later that same year, the Americans largely sat on their hands, leaving the French to fight an increasingly bitter war that, in the end, went so badly that it contributed to Charles de Gaulle leading a military rebellion that successfully overthrew France’s constitutional order.

- Attempts to collude with the British and Israelis in 1956 to seize control of the Suez Canal were met with direct, public, angry American opposition. Not only did the effort fail; the global humiliation shattered the image of France as a major power, spawning a raft of ultimately successful independence movements throughout France’s remaining overseas colonies.

For the country that had been at or near the top of the human experience for the previous millennium, to have the Americans simply blanket the world in their power—to know that France’s recent successes in Europe were possible only because of the American-led Order—on occasion made Parisians break out in hives.

The core issue was, while the Order altered European geopolitics in France’s favor, it also negated many of France’s geographic advantages. Being protected by the Belgian Gap didn’t mean much if Germany was contained within NATO. Having a politically unified system didn’t mean much if the Americans’ barring of imperial predation the world over enabled even shattered systems like China to unify. What had made France special was a geography that made it unified and wealthy and stable and secure. What the Americans offered the world was a system that made everyone unified and wealthy and stable and secure.

In no circumstance was the Order’s elimination of geographic weakness more worrying to the French than in the case of Germany.

The most positive feature of Germany’s geography is its dense webwork of navigable rivers, granting it the best topography on the planet for economic development. The most negative feature is that those same rivers are on Germany’s outer edges rather than in its middle, making it easy for Germany’s neighbors to hamstring German unity. The Order magnified the benefits of the former while eliminating the weaknesses of the latter. Now expressly forbidden from having a military policy, the Germans poured all their efforts into economic and financial growth. It would have been impossible for France to keep up under any circumstances. With France attempting to maintain a military capability independent of NATO and the United States—complete with a fully functional nuclear deterrent—it became laughably so. Had Germany not been lashed to the French will, the disconnect would have been terrifying.

Soon it became so. In 1989 the Soviet Empire cracked apart, and on November 9, throngs of Germans—Eastern and Western—surged onto and over the Berlin Wall. The Americans, sensing a once-in-a-generation opportunity to end the Soviet Union, directly and publicly threw their support behind the budding German reunification discussions. It didn’t take much encouragement for the Germans to, well, plan. Within a year the Germans had legally knitted their country back together. With the Soviet Union’s entire western periphery of satellite states now unrelentingly hostile to Moscow, the Soviet Union itself shattered only two years later.

On the day reunification occurred, Germany immediately became France’s demographic and economic superior. Even worse, German economic linkages quickly started spreading not simply from West Germany into East Germany, but into all the former Soviet satellites. In parallel, the German government started to experiment with—gasp!—independent stances in foreign affairs, flexing its political muscles in the former Yugoslavia. France was, in a word, horrified.

The French strategy for dealing with this unfortunate reality had three pieces.

First, Paris sought to build an anti-German alliance with the intent of surrounding and submerging Germany in the new European geopolitical context. Countries that had sat out the Cold War. Countries that had been on the other side. Anyone and everyone who might prove to be a counterweight to German political and economic power was slavishly wooed. In each and every case, the French government pushed for rapid accession to the European Union, the institution the French still controlled. Between 1995 and 2008, the European Union admitted fifteen new members, including all from the former Warsaw Pact.

Second, the French turned European diplomacy into a co-dominion effort. Rather than asserting that Paris spoke for the entire EU, the French leadership would first court the German leadership and then present joint statements to the world on the EU’s behalf. Such coordination ranged from the purely ceremonial (annual joint meetings of the two countries’ cabinets for some well-choreographed ego stroking) to the deeply substantive (collaborating with the Russian leadership to oppose American efforts in Iraq).

Third, the French sought to constrain the Germans within an economic web to complement the political cage. Paris became an unabashed supporter of the common currency. The French became founding members of the Economic and Monetary Union with the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, and the euro became a reality at the turn of the millennium.

Unfortunately for the French, instead of these three “achievements” ensuring France’s grip on Germany, the strategy instead gave Germany a grip on all of Europe.

First, France’s envisioned alliance against Germany proved to be nothing of the sort.

Throughout France’s long history, it had at one time or another found reason to abandon and/or betray all its would-be allies. Such actions are a derivative of French strength. Unlike the rest of Europe, France could typically feed itself, trade with itself, and unify with itself. The French—and especially the Parisians—see themselves as eternal. As better. In many ways, the French are Europe’s answer to China’s “Middle Kingdom” mind-set. And just like the Chinese, the French tend to see their neighbors as inferior. Disposable. The moment a country is no longer useful as an ally, it becomes useful as an item to be traded away.

People remember stuff like that. Most of the new EU members at least in part blame the French for their fall to the Nazis in World War II, and by extension their domination by the Soviets for the half century that followed. Instead of bowing to French political needs, they proved infuriatingly uppity. Now that all were in the European Union, they had the means, motive, and opportunity to snarl French plans.

Second, while Paris went to great lengths to cultivate German involvement in great-power diplomacy, the Germans had lots of topics they found need to issue statements on that had next to nothing to do with French interests. France couldn’t care less about clearing bridge debris from the Danube in the aftermath of the American bombing of Serbia during the Kosovo War, but as a littoral state, the Germans were keenly interested. France had left the military side of NATO in a fit of pique after the Suez crisis, and so wasn’t a party to military–military talks with the Americans and British as the Germans were—and since NATO expanded right along with the EU, united Germany had a voice in the regional security grouping while France did not. France certainly didn’t want to become guilty by association when this or that Central European or Balkan leader brought up German actions in World War II. In the end, all the French effort did was get the Germans used to being in the spotlight again.

That proved particularly problematic when the third pillar of France’s Germany-containment effort snapped. The euro didn’t generate the straitjacket the French thought it would. One early outcome of the common currency was that all European countries could borrow at interest rates appropriate for the German economic system—a system predicated upon careful planning, measured growth, and fiscal responsibility. Those are not terms normally associated with places like Italy. As soon as Europe’s poorer members gained access to the new currency, they engaged in massive spending programs, funded with cheap borrowing. Social spending boomed, retirement ages dropped, and pension rolls grew as governments tossed cash at citizens and public works projects. For the first seven years, the eurozone economies had growth rates that felt a bit Chinese . . . until it came time to pay for things. For countries like Greece, who were burning cash like a Saudi prince on Instagram, reality hit hard—and it brought receipts.

At first the French didn’t see the euro crisis as a big deal. They had forced the Germans to pay for European integration before: first in the post–World War II settlements, second in transfer payments to bring the weaker parts of Europe up to snuff in the 1970s and 1980s, and third in the expansion of European Union structures to all those new members in the 1990s and 2000s. In inflation-indexed terms, it amounted to some $3 trillion (with France happily carving out the meatiest share for itself). What’s wrong—so the thinking in Paris went—with a fourth tranche? Instead, the unthinkable happened.

Germany said no.

The German government made clear there would be no bailouts . . . unless the countries seeking funds agreed to a series of strict budgetary controls to remake their government spending systems along the lines of the German model. Germany led the negotiations. Germany set the terms. Germany wrote the checks. Germany enforced the deals.

Courtesy of France seeking new allies to constrain Germany, the Germans now economically dominated all of Central Europe. Courtesy of France’s efforts to make the European system a Franco-German duet, the Germans lost their hesitance to stake out public stances. Courtesy of France’s effort to constrain Germany within a new European institution, the Germans ended up dominating the entire eurozone. Paris had not just lost control over Germany. Paris had not just lost control over Europe. The country that France had built the EU to contain now ran the show. By 2016 Germany was more powerful in Europe through political and economic control than it had been at the Nazi zenith, all without firing a shot. All because of French miscalculations.

For the French who can swallow their pride and admit they have lost control of their continent-size creation to the Germans, this living nightmare of the Order cannot end soon enough.

Luckily (if that is the right word), it is ending. The European Union faces any number of internal challenges: demography, exports, currency, migration, banking, financial, consumption—any one of which is sufficient to end it. Hit with all more or less at once in a time of international turbulence, the EU lacks the capacity to cope. About the only way the EU might linger on is if the Germans relent and agree to provide a massive financial backstop of nearly all EU members. Even that is possible only until the Germans hit mass retirement around 2026.

In a world beyond the EU, however, France’s capacity to adapt is robust. The French’s statist preferences discourage the sort of multinational supply chains so prevalent in Germany or China, which in turn slims France’s international exposures compared with its European peers. Of all the Euro-area states, only Portugal and Luxembourg are less dependent upon trade with the outside world. Only Greece trades less intra-EU. Germany, in contrast, is near the list’s top in relative terms, and it is absolutely in the top spot in absolute terms. Post-Order France is the European country that will suffer the least and rebound most strongly.

Even better, France’s strategic freedom and capacity make the French integral to German survival.

France’s expeditionary-themed military is fully capable of reaching places like Libya, Algeria, Nigeria, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Congo (Brazzaville), and Angola. Most are former French colonies. All are oil exporters, and post-Order none have external security providers. France is one of very few countries that can provide technical assistance for their energy sectors as well as security for their commerce. For the energy-poor Germans, such French middlemanning could well prove the factor separating grim success from catastrophic failure.

And considering Germany’s demographic plunge into oblivion, the Disorder’s “solving” of the German question might actually be . . . permanent.

And that frees up French resources to focus on issues beyond Continental Europe.

ISSUE ONE: FENDING OFF BRITAIN

No matter the era, no matter what French politics look like, no matter who has been in charge in London, the French have always considered the English to be a pain in the ass. The French geography is obviously superior in its ability to generate political unity and economic strength. Great Britain is but one-third the land area of France, roughly half the island is broadly useless, and the highlands of Scotland are easily triple the political challenge of the Massif.* While Great Britain is littered with rivers, only one of them—the Thames—is navigable for a long enough stretch to generate a meaningful economic core on its own. Positioning hurts too: the Thames enters the North Sea facing Northern Europe, so should any mainland European power prove capable of floating a meaningful navy, the existence of England itself falls into doubt.

But all that is of secondary relevance to the simple fact that Great Britain is an island. Britain must have a navy, and any navy that France can float will never be able to compete.

It’s an issue of the regional northwestern European geography. Great Britain isn’t simply an island; there are no strategic competitors whatsoever in a roughly 300-degree arc from the island’s south-southwest rolling clockwise to its east-southeast. Denmark and Norway’s interests broadly mirror the United Kingdom’s as regards the European mainland, and Ireland oscillates among satellite, protectorate, and cowering quietly. Any British naval vessel faces minimal challenges in returning home in a crisis and forming up with its sister ships into a single, massive, mailed fist.

The French don’t have that option.

First, the French navy will typically be smaller because, as insulated as France is from its mainland neighbors, the country is still a mainland power with land borders. Once the English conquered those damn Scots, London never required ground forces for defense ever again.

Second, France doesn’t have one coast, but two. It has an Atlantic coast on the Bay of Biscay and the English Channel, and a second one on the Mediterranean. While France’s border with Spain is only 375 miles, the sailing distance between the Atlantic and Mediterranean points on the Franco-Spanish border is over six times that. In a strategic crisis when France needs its navy all in one place for maximum hitting power, the British have traditionally smashed the French fleets in detail with almost contemptuous ease. Even worse, the British have gone out of their way to make Portugal—an otherwise unremarkable Atlantic-facing country on Iberia’s southwest end—its oldest ally expressly to constrain the French from even trying.

Third, the Brits must have a powerful regional navy both for defense and trade, which in the deepwater age puts the Brits a single imperial baby step away from having a globe-spanning navy. Not only does Britain’s naval strength tend to enable it to outmaneuver the French in European waters and well beyond Europe, but it also grants the Brits power and wealth on a global scale—while constraining everyone else. At the British Empire’s height, its rulership of the waves enabled London to dictate terms to any other power that sought to use the ocean for trade—often even in that country’s own coastal waters. That proved triply true for European waters, including French waters. It was galling.

France may boast the best continuity of mainland Europe, but even it suffers a revolution, loses a war, or throws itself a coup every generation or so. France’s governing system at the time of this writing is the fifth constitutional iteration since the Revolution in 1789, ergo the country’s formal name: the Fifth Republic of France. In contrast, Britain has suffered only two continuity breaks since the penning of the Magna Carta in 1215: the War of the Roses and the Protectorate under Oliver Cromwell. It isn’t so much that the Brits have less drama, but that no matter how good a day, year, or century the French have, the Brits pretty much always have it together and they are always . . . right . . . there.

In the coming era, the British will not be in a good mood. The French have gone out of their way to make the Brexit process as painful and punitive as possible, and whoever lives at 10 Downing Street is going to be itching for payback. Under the Order, the Americans would instinctively tamp down such activity to maintain alliance coherence, but those days are gone. In the Disorder, the Brits can draw upon a long imperial experience, rich with examples of how to bring economic, political, and strategic pressure to bear. Trade deals with the Netherlands to stymie French economic primacy. Military support to Greece to hamstring French ambitions in the Balkans. A partnership with Turkey or Denmark to complicate French actions in the Mediterranean and North Seas. Kingmaking in Italy or Spain to limit French penetration into the Apennine or Iberian Peninsulas. Maybe even toying with Germany a little to give Parisians some late-night panic attacks.

London’s strategic options will always be more flexible and have greater reach, and even in those cases where the British suffer massive geopolitical defeats—such as the loss of the American colonies—such losses affect neither the British mainland nor the core of British power: its navy. France, as a continental economy whose power is measured by its ranking and penetration in the European hierarchy, has no such buffer.

But now, as the Order slides into Disorder, for the first time in a millennium, that might not be true. The British navy has been significantly downsized since the Cold War’s end, and at the same time the Brits are attempting to float their first pair of supercarriers. Add recent financial crises and the rising costs of the Brexit drama, and the British navy is so thin that it lacks the ships required to provide an escort ring for those new carriers. The only way the British can field them safely is to do so hand-in-glove with the Americans, and the Americans will undoubtedly think nursing Brexit-related angst requires a tool somewhat less gargantuan than an American-augmented aircraft carrier battlegroup.

In the two decades it will take the Brits to build up and shake down their own rings of escort ships, the French have a window. “All” the French need to do is ensure that any ill will between the Americans and themselves doesn’t rise to the level of ammunition exchanges. Considering that the Americans and French haven’t been on opposite sides of a war for the entire history of the American system, that is probably as safe a bet as can be made as the world ends.

ISSUE TWO: MATTERS OF IDENTITY

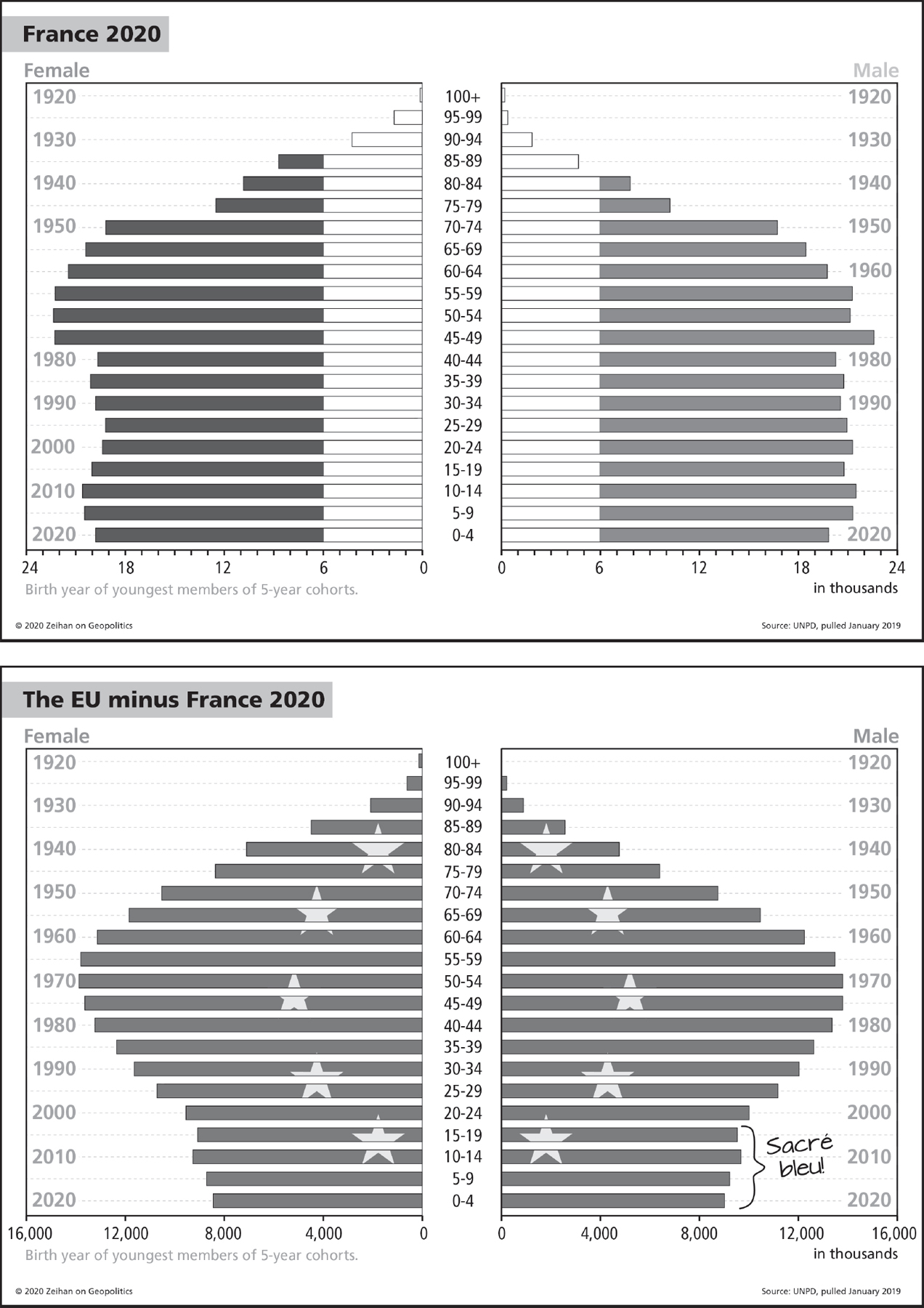

Both Germany’s convulsions and the United Kingdom’s temporary impotence present Paris with historically unprecedented opportunities. France’s next issue has no such silver lining. Like nearly everyone else on the planet, France faces a demographic imbroglio.

First, the good. Yes, France’s birthrate has decreased, and yes, the French demography on the whole is aging, but overall the French demography is very similar to the American: relatively young, relatively stable, aging relatively slowly, and in far, far better shape than the rest of Europe. Post-Order France is the only significant consumption base in Continental Europe, which means post-EU France is far more than highly likely to keep its consumer market to itself. That’s wonderful for French businesses, disastrous for the neighbors.

Now, the bad. France’s demographic problem isn’t with the headline data, but instead a level down, buried in the French national consciousness. Bretons, Basques, Alsatians, Catalans, and more didn’t simply dissolve into the French milieu in the late 1700s. To encourage merger, the First French Republic adopted the motto “liberté, égalité, fraternité,” a declaration similar to the defining American phrase “all men are created equal.”

The differences between the two phrases are telling. The American version proclaims that all are equal before the law, while the French version is a declaration of ethnicity—asserting that all peoples within the borders of France are now part of the French family, and family looks out for one another. With the horrors of the Terror still large in their rearview mirror, the founders of the First Republic took this commitment to fraternal values seriously and strove to make it permanent.

For contemporary France, this has become a problem. There are more people in France than just the French, and you cannot just invite yourself to join a family. You must be invited. Outsiders are rarely welcomed. There’s some truly ugly stuff under this overturned rock.

France was one of the old empires, and in some places the French had ruled not for decades but for centuries. The merger of imperial thinking with liberté, égalité, fraternité meant that the French saw their overseas territories less as colonies and more as extensions of the homeland. That meant including the extended “family” in France’s economic and political integration regardless of where the flag flew: Guyana, New Caledonia, Tahiti, Vietnam, Senegal, Algeria. When the French Empire collapsed, many of those people—many of these citizens—relocated to the imperial center. As years turned into decades, none of the former colonies did particularly well. Trickles of migrants making hay of past imperial commitments followed that first batch to France.

Many French (grudgingly) acknowledge that these imperial imports and their descendants are legal citizens, but they steadfastly, allergically reject the idea they could ever be French. Even if they were born in France. Even if their grandparents were born in France. Resentment runs hot on both sides of the racial divide.

In a world of Disorder, this wedge of disunity in the French system is France’s biggest weakness. It stratifies French society between Frenchmen of Caucasian background and those of the colonial imports. It weakens France’s appeal to African nations. It provides outside powers with a fifth column to exploit. It diverts scarce resources to maintaining civil stability. It creates alienated communities in every major French city. And in the country that invented nationalism—the concept that a country and its ethnicity are inexorably linked—a lack of civic unity on the issue of identity is potentially catastrophic.

Perhaps the most critical aspect of this disunity is that the French have at best only a vague idea as to the scope of the problem. Liberté, égalité, fraternité is so entrenched into French political culture that it is unconstitutional even to collect data on people’s ethnic background. This was done to help merge all the various late-1700s ethnicities into a homogenized system. But now it means France doesn’t know how many of its people are second-class citizens. The figure is probably about six million people, or 10 percent of the population, and it is probably skewed toward the younger end of the population scale. But the nitty-gritty details of the truth are anyone’s guess.

How the French deal with this issue cuts to the core of the very definition of the French nation in the near future. Option one would be for the French to renegotiate their core cultural definitions, to repeat the social experiment of the late 1700s and once again broaden the definition of “French” by adopting the liberal dream: full multiculturalism.

For a country that has bent over backward to make itself as unwelcoming as possible to Polish workers (fellow Caucasians from a fellow Northern European country), as well as to block the immigration of refugees from Syria (a former French colony), it is difficult to envision the multicultural approach happening. What progress the French have experienced in opening their hearts is largely limited to former imperial subjects who are Christian and who speak (perfect) French. Southeast Asians and especially Algerians most definitely are not feeling the love.

Option two is the populist approach. Instead of widening the definition of “French,” narrow it to only include the ethnically French, and maybe a scant handful of other Caucasians who can convince the preexisting French of their enthusiasm for all things France. This requires a logistical pretzel: how does the state act as the social arbiter and strip citizenship from the millions of people who don’t pass the visual or auditory tests for being suitably French? It is with a dark irony that it is France’s late-1700s experience with just this sort of horrific purge that frightened the French into embracing the dream of liberté, égalité, fraternité in the first place.

Between these two extremes, contemporary France pinballs its way forward. Non-French ethnics can have and keep citizenship, but they are de facto forced by the French government and French culture alike to live in the country’s infamous suburb-slums, the banlieues.*

In many ways, the French system takes the two types of racism most prevalent in the United States and applies the worst of both. In the American South, racism takes the form of, “We will mingle, but we are not equal.” In the American North, it is in the vein of, “We are equal, but we will not mingle.” In France, the targets of racism are out of sight and out of mind, consigned to ghettos and at the back of the line as regards government services.

This is a combustible and unsustainable mix, tantamount to occupying a sizeable chunk of one’s own population. In a democracy, even in the best-case scenario, it is a great way to get a lot of people killed.

Never forget that one outcome of liberté, égalité, fraternité is that France is the European country with the highest percentage of ethnic Arabs who are not merely isolated residents, but permanently disadvantaged citizens. Such ghettoization provides terror groups with communities throughout France that have already proved useful for recuperation, recruitment, planning, and refuge from the authorities. Add a disintegrating Middle East, heavier migrant flows, and general European dislocation, and France—already having suffered from more deaths from terror attacks than any other European state—can now fold terrorism into the heart of its identity crisis.

ISSUE THREE: A SOUTHERLY APPROACH

In the Disorder, Northern Europe is certain to be a busy place. Germany and Russia will be locked into struggle until (mutual?) oblivion, while the British will once again be manipulating events and trends European whenever and however they can.

In contrast, Southern Europe is downright sleepy. It is largely an issue of capacity. While Spain and Italy’s extensive ocean frontage necessitates naval forces, both have largely deferred to the United States on security issues. Their current naval orders of battle have a next-to-bottom-shelf feel. On the actual bottom shelf are the naval pigmy states of North Africa; all combined couldn’t fight Spain on the waves. For France, at the Disorder’s beginning the Western Mediterranean is already a French lake.

That hardly means there is no work to do or competitions to wage. France’s Mediterranean challenges will come in three waves, each building upon the one before.

First, there will be issues with the neighbors. Like France, both Spain and Italy import roughly 90 percent of their oil and natural gas from beyond the European continent. Conflict in the former Soviet space will remove what used to be one of the Continent’s three sources. An embittered Britain is unlikely to want to share much that comes from the North Sea and is not above twisting some arms in Norway to keep the sea’s supplies local.

That leaves just North Africa. After years of civil war in Libya and physical destruction and industry mismanagement in Egypt, there isn’t enough to go around. Algeria is the only remaining large-scale producer, but even it cannot quite supply one of the three Southern European powers, never mind all of them. France certainly could defeat both its European neighbors in any contest—France has more money and a bigger market and a better manufacturing base and more guns and a better navy—but what would be the point? Wrecking the Spanish and Italian systems would generate scads of refugees while also ruining some low-hanging strategic fruit.

Better to supply them with energy rather than deny it to them.

To that end, the French must look to West Africa. The headline figures look good: the slew of states from Libya to Angola could supply Western Europe with about 6.7 million barrels of crude and product per day, almost precisely the combined consumption of Italy, France, Spain, and Germany.

If France can keep those flows operational and focused on Europe, France will far and away be Europe’s first power. Spain and Italy will be satellites, and Germany can keep focused on its eastern frontier. It should work. There should be enough to go around . . . but only if nothing—absolutely nothing—goes wrong.

That would be a bad bet. Just as there’s just barely enough oil in North and West Africa for France’s would-be sphere of influence, there’s just barely enough in the North Sea for the United Kingdom’s would-be family in Scandinavia. The United Kingdom’s backup plan will also be West Africa, so right from the start France’s perennial German and British complications will tangle themselves up in whatever else Paris tries to do.

With the margin of error so thin, France has no choice but to expand a second plank into its southern approach. France must get involved up to its elbows in the political guts of North and West Africa simply to maintain stability.

Nigeria’s 8 major and 250 minor ethnicities make it a seething stew of racial violence that killed at least 4,000 people a year since 2013 with a peak of nearly 16,000 people in 2014. Angola is run by a quite literally genocidal family and cannot operate its offshore energy sector without extensive outside help. It doesn’t take an overactive imagination to conceive a Libya-style civil war occurring in Gabon or Equatorial Guinea or Chad that has a similar impact upon oil exports.

For France, that means political and technical support. That means humanitarian assistance and trade. That means bribes. That means maritime convoy systems and troop deployments to ensure smooth operations. It means dealing with or disposing of inconvenient personalities. It means direct military occupations when other means fail. And even that neo-imperial approach assumes that any competition with the British remains more of the good-natured type over tone and approach and accolades rather than a Thunderdome-style melee over who gets to have gasoline next Thursday.

The only way any of this can work is to ensure that additional supplies of crude oil can reach far Western Europe. And that means shifting attention east to a third front.

In any world where the Americans are not providing global maritime security, the Suez connection is the best way to move goods and people between Europe and Asia. Sending fat, slow boats around the African continent is simply asking for them to be stolen by pirates, privateers, or the actual navies of African states. Whoever controls Suez will be able to both make exorbitant transit income and access directly the Red Sea oil exports of Saudi Arabia—and in so doing shape countries on both sides of the link. Success would make France the broker of Europe. And the Mediterranean. And the Middle East. And give France a seat at tables in South and East Asia. What France wants—what France has always wanted—is total control of Suez itself.

But unlike the Western Mediterranean, which is France’s to lose, the Eastern Mediterranean has a lot going on. Lebanon and Syria oscillate between dictatorship and anarchy. Israel always has a firm opinion on security matters. Cyprus hosts a pair of large British naval bases. Turkey is firmly, unapologetically on the rise. Perennially unstable Egypt is . . . perennially unstable. And of course the nexus of Saudi and Iranian interests has been enthusiastically messy since the eighth century.

France, put simply, needs to seize the Suez Canal and a reasonable buffer of territory on both sides so French forces can ensure smooth operation. Luckily, no plan to invade the Middle East has ever gone awry. . . .