2. How Conflict Brings Us Closer

Couples and teams are happier when they are in the habit of passionate disagreement. Conflict can draw people together.

Nickola Overall, a psychology professor at the University of Auckland, was raised in a sprawling, rambunctious New Zealand family in which nobody was shy of speaking their mind. ‘Whenever friends or colleagues meet members of my family, they say to me, “OK I can see why you study direct conflict!”’ Overall is an expert on how and why couples get into rows. She’s interested in romantic relationships because couples are interesting in themselves, but also because ‘The way people try to manage conflict in a relationship tells you about the strategies people use at work or in politics.’

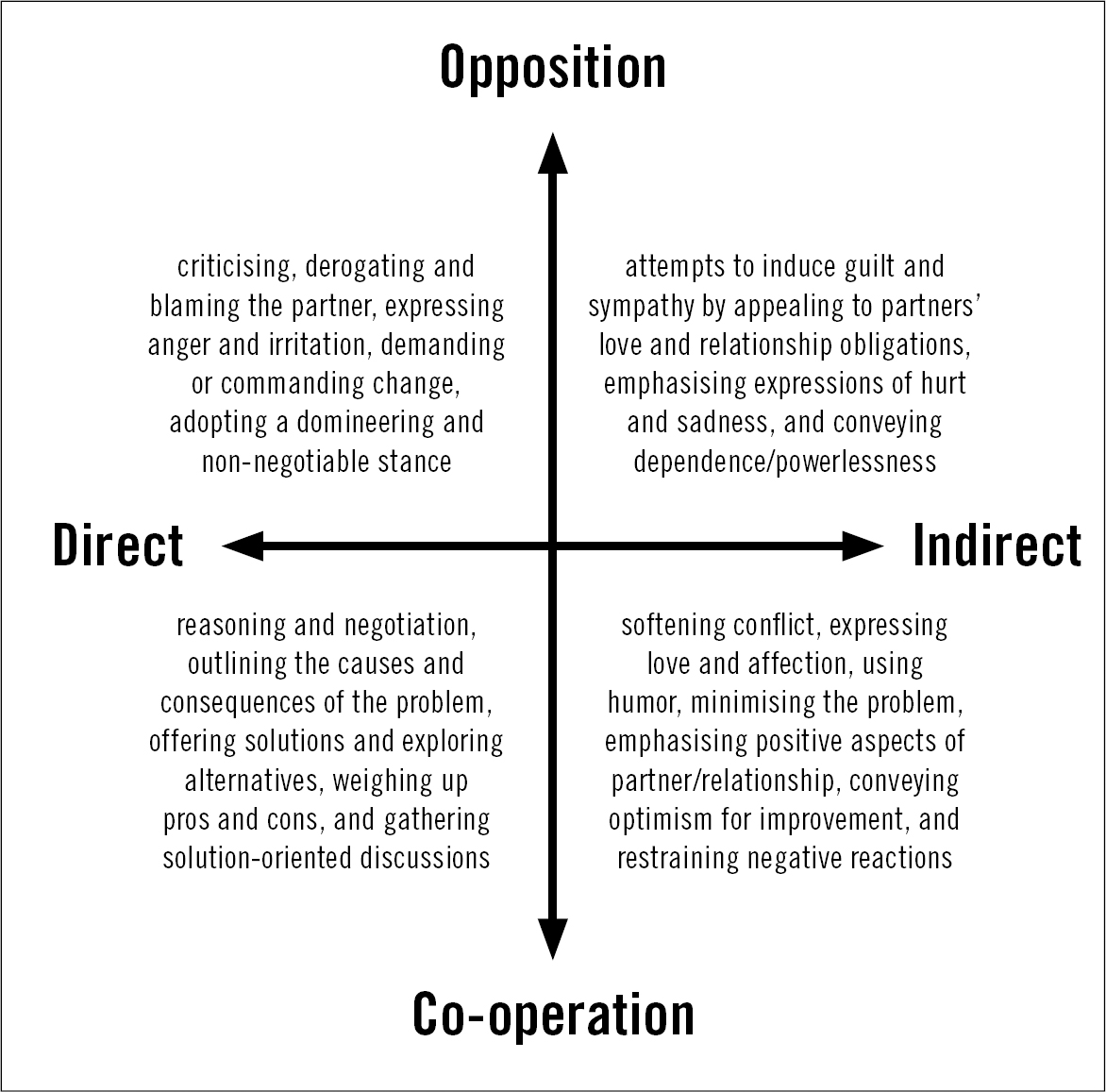

In 2008, Overall began a study of relationships that was to have a lasting impact on her field. She invited married couples to discuss a problem in their relationship on camera, but without anyone else in the room. Some of the couples discussed their problem reasonably and coolly; others got into a heated argument. ‘People often ask me whether couples really get into personal rows in a laboratory but they do, quite easily,’ says Overall. ‘Each couple has two or three things they frequently fight about, and when they talk about one of those things they very quickly expose their anger and hurt feelings.’ Overall and her colleagues then reviewed the tapes of the sessions, analysing each one according to a schema commonly used in the field which categorises four communication styles used by couples having a difficult conversation:

‘Direct co-operation’ involves explicit attempts to reason through tough decisions or to solve problems. ‘Indirect co-operation’ refers to behaviours that soften and reduce conflict, from a hug to an apology or an attempt to lighten the mood. ‘Direct opposition’ is getting into what we in Britain call a proper barney, involving angry accusations and demands for change. ‘Indirect opposition’ is popularly known as ‘passive aggression’ – trying to make the other person feel guilty about something, emphasising how hurt you have been by their actions, ostentatiously declaring that I will clean up the kitchen again, it’s really no problem.

In the post-war years, researchers focused on distinguishing couples mired in hostility from those who mostly got along just fine. Hundreds of studies found that unhappy couples have more arguments, whereas happy couples express more agreement and affection. Conflict was framed only as a problem, the solutions to which were found in that bottom-right quadrant. This gave rise to what we’ll call the standard model of relationships: a happy couple is one in which the partners frequently share their feelings with each other and avoid hostile arguments. But we all know couples who disagree a great deal and occasionally have shouting matches, yet still seem happy; perhaps you are in one of them.

The couples in Overall’s study who engaged in more open conflict stated they did not enjoy it: they experienced tension and felt upset. Afterwards, they told the researchers the conversation had not been successful in solving their problem. But they were not necessarily right about that. When Overall’s team invited the couples back to the lab a year later, they asked them whether they had made any progress towards resolving the problem they had talked about. Most relationship experts would have predicted that the couples who engaged in direct opposition – fierce argument – would have made the least progress. Overall found the opposite: the more confrontational couples were the ones more likely to have made headway in solving their issues.

The standard model has a big hole in it. Open conflict is not always harmful to a marriage or long-term relationship. There is now mounting evidence to suggest something like the reverse: that disagreement, criticism and even anger can, over time, increase marital satisfaction. Falling out has benefits.

* * *

As a young research psychologist at the University of Texas in the mid-1970s, William Ickes was dissatisfied by the way human interaction was only studied under artificial conditions, with participants following strict instructions on what to talk about. He was interested in how well two people were able to read each other’s minds during spontaneous conversation – or, in the jargon of the field, ‘unstructured dyadic interaction’ (a ‘dyad’ is a pair of individuals – a two-person group). Ickes’s resulting body of work offers us a crucial clue to the role of conflict in happy relationships.

Ickes had his respondents, who were university students, arrive at the laboratory in male–female pairs who didn’t know each other. Each pair would be ushered into a room that was empty except for a couch and a slide projector. The experimenter would ask them to sit down and explain that he was going to ask them to view and rate some slides. It would then turn out that the projector was broken, and the experimenter had to fetch a new bulb. Left alone, the pair would strike up a conversation, stilted at first but gaining momentum as the minutes passed. Then the experimenter would return and reveal the real purpose of the experiment. A concealed video camera had been recording the pair’s interaction.

In the second stage of the study, the respondents would be taken into separate rooms to view a tape of their conversation. They would be asked to pause the tape at any point that they remembered having a specific thought, write down what they were thinking or feeling at that moment, and assess what their conversation partner might have been thinking or feeling too. Later, the tapes would be analysed by the researchers, who assigned scores for the accuracy with which any individual was able to read his or her interlocutor’s mind.

In 1957, the influential psychotherapist Carl Rogers defined empathy as the ability to track, from moment to moment, the ‘changing felt meanings which flow in this other person’. But until Ickes, nobody had a way of measuring it. Ickes was the first to find a way to assess a person’s ‘empathic accuracy’ – their success at inferring what is going on inside the head of the person they’re talking to. His methodology has been adapted to the study of many types of dyad, including friends and married couples.

One of Ickes’s major findings about mind-reading is that people are really bad at it. On a scale from 0 to 100, the average empathic accuracy score was twenty-two, and the best scored only fifty-five. (Ickes noted that people on first dates can relax: there’s little chance their companion knows what they’re thinking.) It’s the relationship that makes the biggest difference. Ickes found that friends are better at mind-reading than strangers, because they have a shared store of information about each other, which they can draw on to make quick and accurate inferences. Another way of putting this is that strangers communicate in a low-context environment, in which it pays to be explicit and get all the information out there, whereas friendship is a high-context environment, in which we can deploy heavily coded, highly compressed messages.

Close friends communicate very efficiently and rarely have to make much of an effort to be understood by each other. In contrast, that couple at the next table on a first date have to work really hard at understanding each other, and frequently get it wrong. That said, strangers are quick learners. Ickes found that they got better at reading each other’s minds the more information they exchanged, especially when the information established some common ground or shared interest. Friends exchanged more information than strangers, because the talk flowed more freely, but, importantly, that made little or no difference to their empathic accuracy.

That brings us to something important. Friends and strangers process new information about each other differently. Strangers pay close attention to it because it helps them form a picture of the other person. Close friends, who rely on what they already know about the other person, tend to discount the importance of new information about them. They don’t listen quite as hard because they don’t feel they need to.

Generally, men perform worse on tests of empathic accuracy in couples than women. The evidence suggests that it’s not that men have any less ability to empathise, it’s just that they’re less likely to try. In the lab, offering cash in exchange for accuracy has been found to wipe out the difference between men and women. So it’s not that men can’t detect their partner’s thoughts and feelings, it’s that, for much of the time, they can’t be bothered.

This link between our ability to mind-read and our motivation to do so helps to explain a somewhat disturbing finding from the field of relationship science: that while couples get better at reading each other’s minds in the first months and years of a relationship, the longer they stay together, the worse they become at understanding each other.

During those initial years, each member of a couple builds a mental model of their partner, through which they interpret whatever their partner says or does. Assuming the relationship is a good one, the model will be pretty accurate – to use the language of a statistician, it will be a good fit for the reality of the person. You learn your partner’s predilections and turns of mind. You know that if your partner is grumpy in the morning, it’s probably because they had a bad night’s sleep or are worrying about work. You can tell, when they ask you what you were doing last night, whether they are genuinely interested or whether they’re annoyed at you for staying out. Many of your partner’s utterances that would be opaque or meaningless to others make instant sense to you.

A model like this is a wondrous thing, but in its efficiency is its demise. Once you think you’ve got your partner worked out, you stop noticing new information about them. You might even come to believe that you know them better than they know themselves. However, no matter how close you and your partner are, you are having different experiences every day, and while people tend not to undergo radical shifts in personality as they age, they do develop and change. Over time, as the gap between model and person grows, your reading of your partner worsens. The model becomes an ill-fitted stereotype, a simplified and inadequate image of the real thing. If that process continues for long, it can end in a shocking rupture – like when your partner turns around and tells you they’re leaving.

Talking to each other a lot doesn’t mean you will avoid this pitfall. We’re led to believe that more talking leads to greater understanding, but while this sounds sensible, several studies have found no correlation between empathic accuracy and how much or how clearly couples communicate. Indeed, more communication can lead to less understanding. As the relationship scientist and expert in marital conflict Alan Sillars put it to me, ‘“Talking it out” doesn’t always work. It can make things worse.’ If the model of either or both partners has become a distorting lens, then each partner is consistently making mistaken assumptions about what the other is thinking. The more they talk politely, the more the errors pile up, on both sides. Each becomes increasingly frustrated with the other for not understanding them.

Some couples manage to avoid this fate precisely because they never build efficient models of each other. According to Ickes, the couples most likely to retain their empathic accuracy are those who have either a ‘continuing ignorance of each other’s predilections or an unwillingness to accommodate them’. In other words, ignorance and stubbornness have a role to play in successful relationships. Sometimes it’s good to be inflexible, even when it creates conflict.

In fact, it may be that creating conflict is the point. ‘Listening is one path to understanding,’ says Alan Sillars. ‘So is negativity.’ In a heated argument, you’re more likely to hear what your partner genuinely thinks and wants. You find out what they’re truly like. ‘Conflict provides us with information,’ says Nickola Overall. ‘The way people respond to us in conflict tells us a lot about how co-operative they are, whether they can be trusted, what they care about.’ Conflict in a relationship is not an unfortunate accident. It’s a way of learning about others, including and especially those we know most well.

In 2010, American researchers Jim McNulty and Michelle Russell analysed data from two longitudinal studies of relationships. They found that couples who at the beginning of the study engaged in angry rows over relatively trivial problems were less likely to be happy in their relationship four years later. However, couples who were having hostile arguments about deeper problems, such as money or substance abuse, were more likely to feel good about their relationship by the end of the study period.

In a separate paper, McNulty found that for newlywed couples experiencing serious problems, the kinds of ‘positive’ behaviours encouraged by the standard advice, such as always being affectionate and generous, even hurt some relationships because it stopped the couples facing up to their problems. Indirect co-operation – the softer, subtler approach – can work for minor problems, such as who should be driving the kids to football at weekends, but isn’t great for when a couple has something really important to work through, such as whether one partner is drinking too much.

A measure of ‘negative directness’ seems to be crucial for solving knottier issues. ‘In the short term,’ Russell told me, ‘negative behaviours can make you feel shitty. Nobody likes to be blamed for something or told they’re in the wrong. But it can have this motivational effect. It can really get to the root of the problem.’ Sometimes, one partner simply hasn’t realised that something is a major problem; they need to be enlightened in no uncertain terms. ‘A strong emotional response, yelling and anger, can be needed to demonstrate to the person on the receiving end just how much something means to their partner,’ Russell told me.

In other words, the occasional row is useful because it updates our mental models. People speak their minds freely, uninhibited by fears about how what they say will affect the relationship, and they do it in a way that demands close attention. That means they often – explicitly or implicitly – disclose new information about how they’re feeling and who they are. A good argument blows up the stereotype.

In a study published in 2018, Nickola Overall found evidence for an additional benefit to negative directness: it shows you care about each other. Overall recruited 180 couples and asked each partner, separately, to identify the persistent problems in the relationship, where one partner wanted the other to change. The couples were then asked to discuss one of these problems, in a room together, alone, while being filmed by discreetly positioned cameras. They often got into heated arguments.

Overall and her team coded the interactions for communication style and then checked in with the couples over the following twelve months. She discovered a specific reason that negative-direct arguing can have a beneficial effect on relationship health. When the person arguing for change is previously perceived by their partner to have been less than fully committed to the relationship, their anger, even their hostility, provides evidence that they really do care. Anger is information. ‘Expressing negative emotions can convey investment,’ said Overall.

The same principles apply to other types of close relationship. Parents do not necessarily gain a greater understanding of their teenage children by talking to them about whatever is troubling the relationship. But pressure and confrontation by the child reliably alerts parents to how their children are feeling. Parents who want a deeper understanding of their children can’t simply expect them to ‘open up’ whenever a problem arises. Greater understanding develops over the course of what Alan Sillars terms ‘frequent and unrestrained conversations’. When you keep being candid about the little stuff – including the stuff that annoys you – the big stuff is easier to deal with when it comes up.

‘We’re still not good at painting a picture of the ways in which dramatic and difficult conflict can be constructive,’ says Sillars. ‘Relationships can be deeply troubled at points but ultimately better for the people in them as a consequence of confrontation, if that helps them find a new equilibrium.’ Michelle Russell agrees: ‘Psychology as a whole tends to undervalue the role of negative behaviours and emotions. They can be useful and adaptive. Sometimes you need to feel bad about yourself.’

* * *

Rows may be more useful than we realise, but there is no question that they can be destructive too. What distinguishes the bad rows from the good ones? Answering that question requires us to understand something fundamental about how people communicate.

In an experiment run by Alan Sillars, a wife and husband were filmed discussing their marriage. Afterwards, each of them watched the film separately, and gave their commentary. Here’s a sample of the husband’s commentary:

-Well, Penny is starting to talk about when she was sick in hospital and she doesn’t think I contributed enough at that time or that . . . and I thought I did.

-This is what I get all the time at home, I think . . . I don’t go out all that often.

-I was just trying to explain to Penny here that, uh, in my mind, she is always first to me, even though sometimes it seems like I try harder to do other things.

This is a sample of the wife’s commentary, on the same part of the conversation:

-Now, I think he was trying to avoid the real issues, so I was getting upset and mad again.

-I wanted him to just understand what I was saying so I was aggravated that he was just kind of smirking and not listening.

-I felt hurt because he wasn’t really listening to what I said about my feelings.

You can see there is a mismatch here. The husband is focused on the literal meaning of what’s being said – on the events being referred to and the ostensible point of contention, of whether or not he goes out too much. Meanwhile, his wife tracks the conversation at a kind of meta-level. She talks about the feelings she was having during the conversation, and about her husband’s desire to avoid the real issues.

In any conversation, we’re responding both to its content: to what the discussion or argument is ostensibly about, whether that be money or politics or housework or something else; and also to signals about our relationship: how each sees themselves in relation to the other. The content level is explicit and fully verbalised, and full of concrete references to real-world events, like how much money someone earns or the rights and wrongs of drug policy. The relationship level is implicit and largely unspoken, conveyed as much in our tone of voice and communication style (warm or cold, teasing or sarcastic, animated or taciturn) as in our words. At the content level, there is an exchange of messages; at the relationship level, an exchange of signals.

When the participants are essentially in agreement at this relationship level – when each person is happy with how they think they are being characterised by the other – the content conversation goes smoothly. Problems get solved, tasks performed, ideas hatched. When there is an unspoken disagreement at the relationship level, the crackle and spark of conflict disrupts the content conversation. One or both of the parties find it hard to focus on what they’re meant to be talking about because they’re engaged in an unspoken, unacknowledged struggle to elicit the other person’s respect, or affection, or simply attention. The disagreement either becomes deadlocked or explodes into a damaging row.

According to Sillars, who has observed and coded hundreds of such conversations, when marital disagreements go badly it’s often because one of the partners is only tracking the content level of the conversation and not paying any attention to something that’s going on at the relationship level. It is also possible to err in the other direction: one partner might have an exaggerated vigilance to the relationship level and so misinterpret what the other person says, seeing insinuations or insults where none were made.

It might not surprise you to discover that, according to the data, men are more likely to be guilty of making the first kind of error, while women are more likely to make the second. In fact, men often become so absorbed in their own words that they fail to notice the relationship signals their partner is sending. Sillars has found that, ‘Husbands thought about themselves more than they thought about their partners, whereas wives thought about their partners more than themselves.’ Of course, the confusion can occur in both directions. Either way, the person liable to be getting most upset by the dispute is the person most sensitive to the relationship level. A disagreement is more likely to be productive when both partners are paying the same attention to both levels.

How to achieve that? If you have a particularly acute sensitivity to relationship signals, try not to let them dominate your perception of every conversation. When your partner seems upset or preoccupied, do not assume it’s about you: listen to what they say and engage in the content of the conversation. If, on the other hand, you suspect yourself to be someone who can get so wrapped up in the content of a conversation that you don’t pick up on your partner’s feelings, try and pay more attention to nonverbal signals: the pitch of their voice, facial expression and body language. Otherwise you might hear your partner’s words but miss what they’re saying.

* * *

If conflict can have a surprisingly productive role in romantic relationships, what about the relationships between colleagues? Work is never just about work. The jobs we do are always bound up with our feelings – good and bad – about the people we work with. At the office, even more than at home, we feel pressure to avoid disagreements and the stress and negative feelings that often go with them.

Modern workplaces place a premium on getting along. That’s a good thing, but it means that even when our frustration with someone’s behaviour is perfectly justified, often the smart thing to do is hide it. The unaired conflict doesn’t disappear, however, but manifests itself in office politics, which is essentially the phrase we use for passive aggression at scale. Scholars who study organisations have found that the worst, most unproductive workplace cultures are riddled with passive aggression. That’s why the most successful firms make a determined effort to get their internal conflicts out into the open. Carefully managed, conflict can bring co-workers closer together.

Southwest Airlines might just be the most successful airline in history. In 2019, the Texas-based low-cost carrier celebrated its forty-sixth consecutive year of profitability, a unique record in a volatile industry. Southwest’s success is often explained with reference to its charismatic former CEO, Herb Kelleher, who co-founded the airline in 1967. Kelleher, who died in 2019, was a man of unquenchable bonhomie and he created a corporate culture in his image: Southwest staff are famous for their conviviality and quirky humour. Jody Hoffer Gittell, a management professor at Brandeis University, argues that the firm’s success is not just down to its warm welcome or ukulele-playing baggage handlers, however, but to the way Southwest staff communicate with each other – including how they handle internal conflict.

Gittell spent eight years researching the corporate cultures of airlines during the 1990s. She interviewed staff from the most senior to the most junior, and focused on the major carriers, like American Airlines (AA), United, and Continental. Gittell identified a significant obstacle to profitability: sectarian warfare. The industry, she discovered, has a tradition of status-based competition between the many different functions required to get a plane full of passengers off the ground and back again: pilots, flight attendants, gate agents, ticketing agents, ramp agents, baggage transfer agents, cabin cleaners, caterers, fuellers and mechanics. A ramp agent at AA explained industry politics to her:

Gate and ticket agents think they’re better than the ramp. The ramp think they’re better than the cabin cleaners . . . Then the cabin cleaners look down on the building cleaners. The mechanics think the ramp agents are a bunch of luggage handlers.

The staff used derisive names for other functions (‘agent trash’, ‘ramp rats’) and fiercely guarded their position in a strict hierarchy, with pilots at the top and cabin cleaners at the bottom. A station manager at AA confided in Gittell that ramp workers, ‘have a tremendous inferiority complex . . . the pilots don’t respect them’. A cabin cleaner complained that, ‘The flight attendants think they’re better than us, when they’re sleeping five to an apartment and they’re just waitresses in the sky.’

As Gittell put it, with considerable understatement, the different functions in an airline ‘typically lack shared goals or respect’. During her research, she kept hearing about an airline called Southwest, which was said to be different, and so she began to study it. The contrast was dramatic. Staff across different functions seemed to respect and even like each other. Pilots appreciated the work of ramp agents, and cleaners got along with cabin crew. This culture of respect didn’t just make Southwest a more attractive place to work; it was the reason for its profitability.

The vision of Kelleher and his co-founder Rollin King was to provide frequent, low-cost flights of under 500 miles in busy markets. This was brave, since short-haul flights are inherently costlier than long-haul ones. The more time a plane spends on the ground, the less money it makes, and planes that fly shorter routes land more often. What enabled Southwest’s counter-intuitive strategy to work was its relentless focus on reducing turnaround time, that time spent getting a plane ready for the next flight. Quick turnarounds are impossible without a high degree of co-ordination among all the airline’s functions. Pilots, flight attendants, baggage handlers and others must constantly communicate any snags in the process and find immediate solutions. To do that well, they need to get along and they need to care about the success of the whole company. Southwest’s culture of collaboration means it has the fastest gate turnarounds in the industry. One of its managers told Gittell, ‘Sometimes my friends ask me, why do you like to work at Southwest? I feel like a dork but it’s because everybody cares.’

It’s not that staff from Southwest’s different functions don’t clash with each other. Argument and annoyance are inevitable in any activity that requires a lot of close and complex co-ordination. But instead of turning their mutual frustrations into seething antipathy, Southwesters air them directly. As one station manager put it to Gittell, ‘What’s unique about Southwest is that we’re real proactive about conflict. We work very hard at destroying any turf battle once one crops up – and they do.’

* * *

Until relatively recently, academics who studied management assumed that workplace conflict was bad for productivity. But, as with marital relationships, there’s now an increasing recognition that conflict can have positive effects – and that avoiding it is harmful. In ‘conflict-avoidant’ workplaces, staff think of conflict only as a dangerous, destructive force that must be shunned. The result is that differences of opinion are channelled into passive-aggression. An employee at an online education service that exemplified this culture told the leadership expert Leslie Perlow, ‘I noticed early on that colleagues weren’t being frank with one another . . . they smiled when they were seething; they nodded when deep down they couldn’t have disagreed more. They pretended to accept differences for the sake of preserving their relationships and their business.’

A crucial challenge for any organisation is to ensure that its employees conceive of conflict as something other than personal rivalry. Management scholars make a distinction between task conflict – arguments over how to solve a problem or make a decision – and relationship conflict, when things get personal. Task conflict, even when it’s heated, can be collaborative and productive, if the participants care about solving the same problems. As we’ll see later, it flushes out new information and stimulates critical thinking. Relationship conflict is inherently competitive, and usually destructive: personally conflicted groups make inferior decisions, and the people in them feel less happy and less motivated. This holds true in studies of students and professionals, blue-collar workers and executive teams.

The border between task conflict and relationship conflict is a messy one: conflict over a task often slides into personal competition. Evidence suggests that when people interpret disagreements as personal attacks, their cognitive function is impaired, in two principal ways. First, they become rigid in their thinking, clinging to the first position they choose, even when it is shown to be wrong. Second, they engage in ‘biased information processing’: new information is only absorbed insofar as it fortifies their position. In short, they become exclusively focused on proving themselves right rather than helping the group be right, which makes the group itself a little more stupid.

The organisational psychologist Frank de Wit has examined how a difference in mindset explains why task conflict can tip over into relationship conflict. He draws on a distinction from the science of stress, often used in sports psychology, between threat states and challenge states. When people evaluate a potentially demanding task, like making a golf putt or giving a public speech, they make an instinctive calculation of whether they have the resources to deal with it. If they feel they do, they go into a heightened state of mental and physiological readiness – the challenge state. If they feel they might be overwhelmed by the task’s demands, they focus mind and body on fending it off – the threat state.

Challenge and threat states have different physiological markers. In challenge states, the heart beats faster and also becomes more efficient, maximising the amount of blood it can pump to the brain and muscles. In threat states, the heart beats faster but it doesn’t pump more blood. Blood vessels in the heart raise resistance, constricting the flow. Hence the distinctive sensation of anxiety, of being agitated and trapped at the same time. Challenge states involve a measure of anxiety, too, but in a way that converts into physical and cognitive horsepower. In lab experiments, people in challenge states have superior motor control and perform better on mentally demanding tasks, like brain teasers, than people in threat states.

In a series of experiments, de Wit looked at how people responded to direct disagreement in group discussions. He monitored each participant’s physiological responses, while assessing their debating tactics. The more that each participant’s cardiovascular measures indicated that they had switched into threat state, the less likely they were to shift from the initial opinion and the more likely they were to screen out information that didn’t help them win the argument. Participants in a challenge state were more open to divergent viewpoints, and more willing to revise assumptions.

When people feel challenged but not threatened, confident they can handle the disagreement without losing face, they can take a looser grip on their own arguments. That prevents the discussion from degenerating into a personal competition, and keeps the group focused on solving the problem at hand.

Different managers approach team conflicts in different ways. Some try and avoid it altogether; others actively foster a culture of confrontation. Researchers who studied a successful technology firm in the late 1990s observed that, ‘Both male and female senior execs were expected to conform to dominant norms: brutal honesty and controlled anger – which often coalesced in the form of screaming arguments that had a scripted, playacting quality.’ Theatrical confrontation was also central to the culture of a tech firm known by the pseudonym Playco, studied by the sociologist Calvin Morrill. One employee defined what it means to be a strong executive at Playco: ‘A tough son of a bitch, a guy who’s not afraid to shoot it out with someone he doesn’t agree with, who knows how to play the game, to win and lose with honour and dignity.’ Superiors and subordinates were expected to ‘joust’, and someone was always judged to have ‘carried the day’ (not necessarily the superior). Skill in jousting was a key component of evaluations. ‘We’re sharks circling for a kill,’ said another Playco executive. ‘If someone takes a bite out of you, you take a bite out of him.’

A confrontational culture can facilitate rapid decision-making because weak arguments get quickly weeded out. It works best in organisations that are scrambling to adapt to change. But it encourages fierce personal competition, which distracts from the task at hand. It also – and this is just my personal intuition – selects for assholes. The sweet spot is a culture in which conflicts are played out in the open but everyone is focused on the group being right rather than proving themselves right, a culture in which disagreement is a challenge to be met rather than a threat to be repelled.

If you’re a relatively junior employee in a company riven by toxic confrontation or passive-aggressive politics, there may not be much you can do about it except try not to let the culture define you, and look for another job. If you’re a leader, however, you can do a lot more. You can model positive disagreements with close senior colleagues, letting everyone know, implicitly and explicitly, that people at this workplace can disagree vigorously and still get along. You can convey to members of your team that if you disagree with them openly, it’s not because you don’t respect them but because you do. In workplaces where tough decisions have to be taken at speed, communication needs to be direct to the point of abrasiveness; there is little time for subtlety or politeness. The psychologist Nathan Smith, who studies leadership under pressure, told me that he advises senior hospital doctors to prepare junior medics in advance for this style of interaction, so that they don’t feel personally persecuted when on the sharp end of it.

Organisations can also introduce simple processes which allow frustrations to be aired and resolved. Relative to other airlines in Jody Gittell’s study, Southwest had by far the most proactive approach to conflict resolution. Her analysis suggests that this resulted in faster turnaround times, greater productivity, and fewer customer complaints. A Southwest Airlines employee told Gittell, ‘Where there’s really a problem [between functions], we have a “Come to Jesus” meeting and work it out. Whereas it’s warfare at other airlines, here the goal is to maintain the esteem of everybody.’ The meetings were officially termed ‘information-gathering’ sessions before acquiring their more soulful nickname. They have a regular format: one side gives their version of the problem, then the other gives theirs, before a consensus on the way forward is reached.

Managers at the other airlines studied by Gittell tried to ignore internal disagreements altogether, but when one of them, United, started a new unit, ‘United Shuttle’, its leaders decided to emulate Southwest’s proactive approach. After Shuttle outperformed the rest of the company, the mainline operation began to hold conflict-resolution sessions too. A ramp manager told Gittell what a difference it made: ‘At first we would blame them and they would blame us. So we started having joint meetings, twice monthly. At first they were bitch meetings. Now they’ve evolved into “I can take that on, I can do that.”’ One meeting in particular was the turning point: ‘The meeting started out with attacks on management and attacks on each other. Terry [a senior manager] came in with flip charts and thought it was chaotic. But Charlie [a middle manager] said it’s the best meeting we ever had. Everyone spoke their minds, and people were saying, “Here’s what we’re going to do.”’

* * *

John Gottman, one of the founders of modern relationship science, proposed that the behaviour most deadly to a relationship is contempt, because contempt represents an attack on another person without any focus on the problem, any pretence of a common goal. Nickola Overall agrees that contempt is destructive, but even here, she said, there may be a buried signal waiting to be uncovered. ‘I believe that all emotions are important social information. Even with those difficult negative emotions you can sometimes get a glimpse of the other person’s perspective. You can get a sense of their dissatisfaction and pain.’ That doesn’t mean negativity should always be interpreted sympathetically: ‘Sometimes, the information you’re getting is that this person can’t be trusted; that they’re not committed to you. The ultimate goal shouldn’t always be resolution. Sometimes you need to end the relationship!’ But it does mean that there is a role for negative emotions in healthy relationships.

Of course, there is always a risk that a row will get out of hand and damage the relationship we have with our partner, friend or colleague. Awareness of this risk is what leads so many of us to avoid conflict whenever possible. It’s what stresses us out about the prospect of even a mild confrontation. What we tend to under-estimate are the risks of not airing our differences. When we don’t expose our relationship to the relatively minor stress of a candid disagreement, at least two dangers loom.

One of them is that our frustrations, instead of going away, manifest themselves in low-level sniping. Researchers disagree on many issues concerning the complexities of relationships, but one of the clearest findings of the field is that there isn’t any useful role for passive aggression. The evidence suggests that ‘indirect opposition’ is almost always a waste of time, whether that’s at home or in the workplace. It neither motivates anyone to change, nor resolves any problems; all it does is corrode trust. If we reach for it often, it’s because we want others to know when we are hacked off but are too anxious at the prospect of confrontation to be upfront about it.

The second danger is that we stop learning about each other until, one day, we discover it’s too late. What can you learn from a row? You can learn what, or who, that person really cares about. You can learn how they see themselves – which may be different from how you see them, no matter how well you think you know them – and you can learn how they see you.

Under the right conditions, conflict unifies. It can also force people to consider other perspectives, think more deeply about what they’re trying to accomplish, and fertilise new ideas. In other words, it can make us smarter and more creative. That’s what the next two chapters are about.