Late in 1937, Norman Bethune finally found his cause. He was forty-seven. He had no children. After the departure of Frances, his personal life was empty. His career was in ruins. All the things that had been important in his life before—his partying, his art collection, his medical practice—seemed irrelevant. All that was left was the fight against Fascism. Fascism was a disease, just as deadly as the tuberculosis he had fought so long to eradicate. And it had to be fought just as ruthlessly. Bethune was a brilliant, innovative doctor and Spain had toughened him. Where could he do most good? The answer lay across the Pacific Ocean.

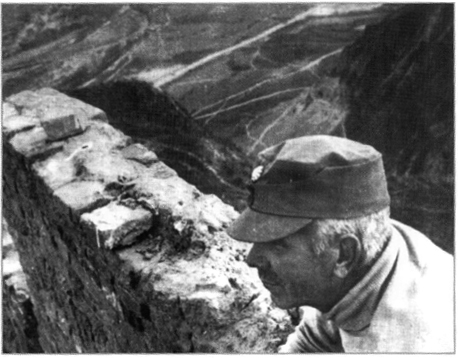

This famous photo shows Bethune on the Great Wall of China.

On July 7, 1937, while Bethune was speaking in Timmins, Ontario, the Japanese army invaded China. Japan at the time had an Emperor but was controlled by its army, and the army wanted an Empire. In 1931 they had taken Manchuria away from China, now they wanted the rest. At first the Japanese swept through China and captured the capital Nanjing, where they murdered 350,000 people. The Chinese army was no match for the ruthless, efficient Japanese soldiers. The exception was the Communist Eighth Route Army led by Mao Zedong. They were not well equipped, but they were battle hardened after years of fighting against the Chinese government. Now they controlled a large, remote area in Northern China where they fought desperately to stop the Japanese invaders. That was where Bethune could help best.