PART I

Buddhism in Time

A vision awakens us

From the depths of ancient history

Buddha’s enlightenment

Dispels the shadows of mystery

—C. Alexander Simpkins

Buddhist philosophy spans twenty-five centuries, with millions of adherents throughout the world. The journey began in a shadowy past, before recorded history, when a legendary man named Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, through dedicated effort and commitment to all human beings, made a wondrous discovery: that life can be good, and so can we. As you follow the evolution, the veil over these shadowy beginnings lifts, revealing a brightly lit pathway of inner discovery, open for all to walk.

CHAPTER 1

The Founder Plants the Seeds

Be a lamp unto yourself.

—Buddha

EARLY YEARS

Buddhism can be traced back to one man, known to the world as the Buddha, “The Awakened One” (563-483 B.C.). He began his evolution as Siddhartha Gautama, a member of the Sakya clan of a small republic in northern India. During this time, India was divided into many small, independent kingdoms, each ruled by clans. Buddha’s father was the raja, or leader, of the Sakya clan area, and his family was wealthy.

Suddhodana, Buddha’s father, gave his son every opportunity to learn and grow, teaching him all the skills a prince should have, bringing in the best tutors, who taught young Siddhartha the Hindu classics. He rode his own horse, practiced martial arts, and played the popular sports of the day. He led the active and happy life of a child of privilege.

Siddhartha’s gentle-hearted nature began to emerge early. One day, young Siddhartha was playing in the garden with his cousin Devadatta. As a flock of wild swans flew overhead, Devadatta drew his bow, aimed at one of the swans, and shot. The arrow hit the bird’s wing, bringing it down. Siddhartha ran over to the struck bird and gently held the bleeding creature until it became calm. When Devadatta claimed the bird as his conquest, Siddhartha refused to give it up. They argued, but in the end, Siddhartha won. He took care of the bird until it was healed and then set it free to rejoin its flock.

Siddhartha continued to remember the bird’s suffering. Suddhodana saw his son’s mood and tried to protect him even more from anything unpleasant. He lavished on Siddhartha all that he could give, including beautiful houses and delicious foods. He arranged Siddhartha’s marriage to Yosadhara, the most beautiful girl in the kingdom.

DISCONTENT

Siddhartha lived happily with Yosadhara, never leaving the confines of his comfortable palace. Although he doubted the importance of the pleasures that filled his everyday life, he continued to feel happy.

One day Siddhartha went outside the palace gates with his servant, Channa. An emaciated man, wracked with pain, appeared on the roadside. “Alms for the poor!” the man called out. Siddhartha stopped the chariot and asked Channa, “What is wrong with this man? Why does he suffer so?”

Channa answered, “This man is ill, my prince. Many suffer from illness. This is the way of life!”

Siddhartha, who had only known good health, felt deeply troubled. They continued along and came to an old man, bent over, shaking, leaning on a twisted cane. “Now, what is wrong with this man? Why does he suffer so?” asked Siddhartha again.

“This man is old, my prince. We all grow old and die eventually. This is the way of life!”

Siddhartha returned to his palace but felt no peace of mind. He could not stop thinking about the suffering he had encountered. All the beauty and joy of life was only transitory! People grow old, perhaps even become sick, and die. Was there nothing more permanent, more real to life? Day after day, night after night, he wrestled with the problem of suffering. Despite his love for his wife and their baby boy, Rahula, he resolved that he must leave the palace to seek answers for his people, to help them.

YEARS AS AN ASCETIC

At the age of twenty-nine, Siddhartha crossed through the palace gate for the last time. He joined a group of ascetics who had denounced worldly pleasures to seek higher truth through a form of Hinduism. The ascetics viewed the human body as the enemy of the soul. They believed that the body could be tamed through absolute denial of physical pleasures, freeing the soul to soar.

Siddhartha found a teacher, Alara Kalama, who taught a form of meditation that attempted to reach beyond the everyday world to a state of nothingness. Siddhartha soon mastered this technique, achieving a state of nothingness, but found that even though he could achieve this state, it did not solve the problems of suffering and death.

Disappointed, Siddhartha sought a new teacher, Uppaka Ramaputta. Siddhartha had heard that Uppaka taught a meditation system that brought about a state of neither consciousness nor unconsciousness. Siddhartha worked diligently at this method and eventually reached this state, but he did not feel any closer to eradicating suffering.

So Siddhartha decided not to look for another teacher and traveled alone instead. He walked southward into the kingdom of Magadha where he met five other seekers. They recognized his intensity and decided to join him in hopes of learning from him. They all lived in the woods.

Siddhartha experimented with many kinds of meditation, always pushing the limit. He tried austere practices, restraining his body, reducing his food to one grain of rice per day. He tried suppressing his breathing to the point of convulsive pains. Day after day he sat motionless in meditation. He endured heat, rain, wind, hunger, and fatigue. He sat so still that birds perched on his shoulders and squirrels sat on his knees.

ENLIGHTENMENT

Seven years passed. Siddhartha had endured the elements without wavering in his self-denial, yet he felt he had made no progress. Instead of finding truth, his mental powers were dimming, his life was slipping away. One evening he was struck with a realization: If he continued, he would die without relieving his people’s suffering. How could his mind reach farther?

That night Siddhartha took some fresh milk and rice from a kindly woman. He sat down under a bodhi tree, a type of fig tree known as ficus religiosos, that has come to mean “wisdom tree.” With renewed strength and hope, he sat down and resolved to meditate until he found the answer to suffering.

As the sun rose, Siddhartha was illuminated with inner wisdom. The answers to all his questions became crystal clear. He experienced a wordless realization, a dissolving of suffering, an intuitive understanding of life and death. He arose radiant and strong, fully enlightened. From then on, Siddhartha Gautama became known as the Buddha.

DEVOTION TO TEACHING AS BUDDHISM GROWS

Buddha hesitated at the bodhi tree following his enlightenment. At first he considered remaining silent. He knew that most people, because they were entangled in worldly attachments, would be unwilling to take his advice. But his compassion for humanity drove him back to the world. After all, he had finally found the answer to suffering. His enlightenment brought him absolute relief and happiness. He wanted to share his wisdom with others.

Buddha sought the five ascetics who had shared many years with He found them living in the Deer Park, located three miles north of Benares. When he approached them, they refused to recognize him as enlightened. From their perspective, he had proven himself too weak to adhere to the strict ascetic path. But Buddha confidently explained his basic insights, and what he said has come down through the centuries as his first teaching, the Sermon at Benares. Neither the ascetic path of deprivation that made him sick, he said, nor the way of complete indulgence that made him dull, could bring an end to suffering. He had come to realize that the body must be optimally fit and healthy to withstand the mental rigors required to reach enlightenment. The Middle Way, the path between, was the true path. Buddha laid out the method by which to follow this middle way in the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path (see Chapter 6).

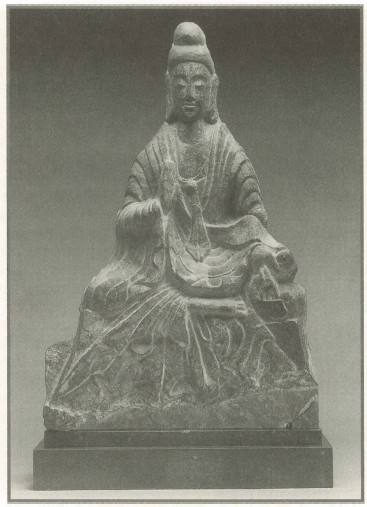

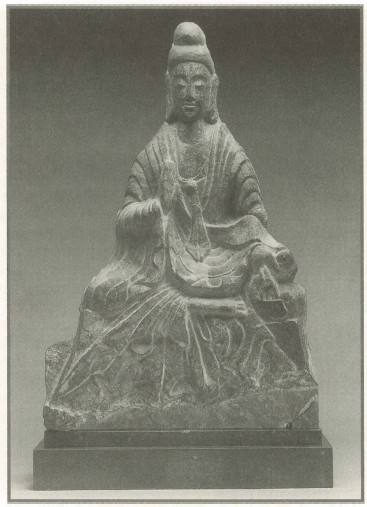

Buddha. China, Northern Wei dynasty, Limestone, 500-525. Gift of the Asian Arts Committee, San Diego Museum of Art

Four of the five ascetics reluctantly sat around him to listen, yet after he expressed his realization to them, they were all converted. They joined him and began teaching his path, thus marking the birth of Buddhism.

Buddha and his small band of disciples walked from place to place, spreading the message and gathering followers. Their days were spent traveling, begging for food, eating, bathing, and then listening to talks from Buddha before traveling on.

On the journey from Benares to Rajagriha, another large city in northern India, Buddha met Kasyapa. Kasyapa and his two brothers were leaders of a large fire-worshiping sect of over a thousand ascetics. At first, Kasyapa did not believe that Buddha held any special knowledge. Buddha convinced him with a discourse that has come to be known as the Fire Sermon. The entire group sat together in an area called Elephant Rock overlooking Rajagriha valley. Just then, a fire broke out in the jungle on a nearby hill. Buddha seized upon this natural occurrence to teach.

Like the fire that was consuming the trees, plants, and animals, so our passions consume us, he said. Whenever we see something, it ignites an inward reaction of either pleasure or pain. Our sensations fuel these inner fires, consuming us in a never-ending inferno of desire for pleasure and fear of pain. Buddha taught that the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path free us from these fires. Then we can see without craving, free to be happy. This sermon convinced Kasyapa that Buddhism offered a true path for him.

Kasyapa, along with his two brothers and many of his followers, joined Buddha in his travels. Kasyapa became Mahakasyapa, one of the primary disciples who organized the Order after Buddha’s death. Through his travels, Buddha continued to gather followers and supporters from all levels of society. His willingness to accept anyone, no matter what their caste, was a radical departure from traditional Hindu protocol. Usually religion had been taught in Vedic Sanskrit, a language used only by the upper castes. Buddha felt that teaching in Vedic Sanskrit would make it impossible for anyone from lower castes to understand his sermons. Thus he always used the common language.

When the group arrived in Rajagriha, they were met by the ruler of the area, King Bimbisara. On hearing Buddha lecture, the king offered Buddha a residence in one of his nearby bamboo groves. Buddha and his disciples spent many rainy seasons in this grove, and it was here that Buddha delivered some of his most complex speeches. During his first year there, Buddha converted Sariputra, who was later involved in many conversations with Buddha, recorded in the sermons. Sariputra joined the community, called the sangha.

Buddha’s father had kept track of his son’s progress through the years, and eventually he sent a message asking Buddha to make a visit. Buddha decided to return to his home with his entire company. They arrived in a local park and, as was their custom, went from house to house begging for food. The town watched, somewhat horrified to see their prince dressed in simple robes, extending his begging bowl. Suddhodana walked up to his son and confronted him, “Why do you disgrace the family?”

Buddha replied, “Your lineage is of princes; my lineage now is from buddhas who have always begged for their food.” Still, Buddha did not want to hurt his father, nor did he wish to show him disrespect. He continued, “When someone finds a treasure it is his duty to give it to his father. And so, I offer to you, Father, my most precious treasure: my doctrines.”

After listening carefully, Suddhodana could see that his son was following an honorable path. Without uttering a word, Suddhodana took his son’s bowl and gestured for him to enter the palace. The entire household honored him, solidifying their bonds in a new way. Eventually, many of them joined Buddha’s group.

For forty-five years Buddha preached, traveled by foot around the area of northern India, and returned during each rainy season to the bamboo grove. Although many people accepted his teachings without question, some voiced objections. Devadatta, Buddha’s childhood companion, tried to convince Buddha to become stricter. He believed monks should be required to live outdoors, wear rags, eat no meat, and never accept invitations to join people for a meal. Buddha said this was unnecessary. As long as people were not overindulgent, it was not important where they slept, how or where they ate, or what they wore. Dissatisfied with Buddha’s answer, Devadatta founded his own conservative order, and gathered many supporters. Throughout Buddha’s career he encountered people who objected to aspects of his message. These dissenters were the precursors to the divisions that would take place years after Buddha’s death.

BUDDHA’S FINAL DAYS

During the rainy season of his eightieth year, Buddha became ill and realized that his life was drawing to a close. He gathered all his followers around him. Speaking earnestly, he directed them to continue following the way he had set out so that the teachings could live on. He told his disciples, “Mendicants, I now impress upon you, decay is inherent in all component things; work out your salvation with diligence!” (Rhys Davids 1890, 83). These were the last words he spoke before he slipped away, peacefully. The year was recorded as 483 B.C.

CHAPTER 2

Buddhism Takes Root

The disciples of Gotama are always well awake, and their mind day and night always delights in meditation.

—Dhammapada

THE FIRST COUNCIL

The funeral ceremonies began, but the monks in attendance agreed to wait for Mahakasyapa to return from his travels before they performed the cremation. Meanwhile, Mahakasyapa met a group of monks in the village of Pava who informed him that Buddha had died. One of them remarked, “Don’t be unhappy. We are finally free to do as we wish without being reprimanded and corrected all the time!” Concerned about the rebellious sentiment, Mahakasyapa hurried back to the funeral site to complete the rites.

Following Buddha’s death, many members of the Order dispersed. There was nothing to keep them together. Mahakasyapa recognized that something had to be done to formally set out the rules and teachings of Buddha to keep the Order gathered. Three months after Buddha’s death, Mahakasyapa called together the five hundred who remained. They gathered at a place near Rajagriha into what has come to be called the First Buddhist Council.

All who gathered had reached enlightenment except Ananda. Ananda had been continually at Buddha’s side for the past twenty-five years and knew all of Buddha’s sermons by heart. Therefore, the monks agreed that Ananda should be included at the council.

Ananda desperately wanted to become enlightened. According to legend, the night before the council convened he stayed up all night trying to reach enlightenment. Unsuccessful, he finally decided to give up and go to bed. When he lay down on his bed, so the legend goes, his head mysteriously lifted off the pillow and his feet raised from the bed. He became enlightened.

The five hundred monks spent the three months of the rainy season gathering Buddha’s teachings, preserving them in three sections: the words of the Buddha, called the Doctrines of the Elders (Thera Vada), the rules of the Order (Vinaya), and the general precepts for both the monks and the laity (Dharma). Ananda recited the sermons as he remembered them, beginning each one with the words: “Thus have I heard,” which is how the earliest sermons, later known as sutras, begin.

The entire council recited all the information together to commit it to memory. According to the custom of the time, nothing was written down. Our respect for the written word was not shared by early civilizations. Originally, people believed that sacred words would be trivialized, their deeper intent lost, if they were written down. Important information was best preserved when learned by heart. As a result of this belief, for several centuries Buddha’s lectures were perpetuated solely in the memory of the monks.

The monks continued to walk the Eightfold Path that Buddha had shown. Through meditation that helped them recognize impermanence and give up desires, they sought to find enlightenment. They became known as arhats, followers of the saintly, noble way, and they lived in seclusion so as to foster and develop their enlightenment. Through deep meditation on the Eightfold Path, they escaped the problems of sickness, death, and suffering. The reputation of arhats as absolutely pure beings grew.

BUDDHISM DIVIDES INTO SECTS

For the next hundred years, differences that had always been present, even during Buddha’s lifetime, became more pronounced. Some followers felt that the traditional rules and practices set out by the First Council were too strict. A second council of seven hundred monks was called at Vaisali to resolve the divisions and set down the rules and teachings as they had developed. One contingent of more liberal monks requested what was called the “Ten Indulgences,” asking for the loosening of the rules and restrictions on alcohol, money, and behavior.

In the end, the council upheld the conservative version of the rules without change. Dissatisfied with the council’s decision, members of the liberal faction, under their leader Mahadeva, held their own meeting, which they called Maha Sangiti (the Great Council). This was the origin of a new sect of Buddhism, the Mahasanghikas, which paved the way for Mahayana.

After the Second Council, the monks continued to wander around the countryside in groups, teaching the doctrine from memory. Each member tended to specialize, becoming expert in one sutra. Inevitably, variations began to occur. People and groups not only lived in different parts of the country, but also learned different doctrines. At first, the groups got along amicably, recognizing that they were simply traveling different paths to the same goal. But gradually, distinctions became disputes that grew more frequent and intense. At least eighteen separate sects formed.

Since all the orders depended on the general population for support, the liberal Mahasanghikas wanted to relax the strict rules about who could be enlightened so that everyday people could be included. Mahadeva argued, “Why not put your faith in the Buddha who achieved perfect enlightenment and remains forever in Nirvana?”

The conservative sect adversarial to the Mahasanghikas called themselves Sthaviras, meaning Elders. In Sanskrit, this name translates as Theravadins, one of the Buddhist groups that continues today in Southeast Asia. Theravadins claimed that they had seniority and were the keepers of Buddha’s original orthodoxy. They tried to stay with the early traditions without changing them. To let go of passions, discover wisdom in meditation, and then become an arhat continued to be the highest goal for these followers.

The sects disputed other issues, but the major division was between the Elders and those who preferred a more liberal doctrine.

ASOKA, THE BUDDHIST KING

Asoka (ruled 274-236 B.C.) began his career as a military leader. After conquering Magadha, Asoka was crowned king, and each of his six brothers was given his own city to rule. Asoka, however, did not get along with his brothers and attacked their kingdoms repeatedly. Eventually, he was victorious, brutally killing all six. He continued his murderous rampage until the entire territory was his.

Many legends tell of Asoka’s cruelty. He believed that the more people he killed, the stronger his kingdom would become. He built a sacrificial house where executions were performed and decreed that anyone who entered the house was to be killed. He was said to have slaughtered thousands of innocent people (Chattopadhyaya 1981, 54).

One day a young Buddhist seeker named Samudra, who had not yet found enlightenment, wandered into the sacrificial house by mistake. Raising his sword, the executioner approached the monk. Samudra asked innocently, “Why are you attacking me?”

The executioner explained, “Now that you have entered this house, I am obliged to kill you.”

Samudra said, “I will accept that, but leave me here for seven days. I will not move from this spot.” The executioner agreed and left. The monk sat down amid all the blood and began to meditate. He could see the remains of the many lives that had been cut short. Suddenly, as he realized the impermanence of all things, he was enlightened.

On the seventh day, the executioner returned to kill Samudra. Thinking of a new way to accomplish this chore, the executioner placed Samudra in a cauldron of burning oil for a whole day, but Samudra was now impervious to harm. Hearing about this strange event, the king strode into the house to see for himself. The executioner looked visibly upset. “Sire! You have entered the house, and now by your own order, I must kill you!”

But Asoka cleverly countered, “Ah, but you entered first, so I must first kill you.”

The monk interrupted their arguing. “I have miraculously been able to endure this burning oil because of my meditation!” In a persuasive speech about the benefits of Buddhism, he urged the king to repent of his sins. Deeply moved, the king underwent a complete conversion. He destroyed his slaughterhouse and put all his efforts into learning and practicing Buddhism.

King Asoka did more than any previous ruler to spread Buddhism. He urged his citizens to follow the guidelines of Buddhism: to become moral, act justly, and live lives filled with love and compassion. People should obey their parents, respect living creatures, tell the truth, and revere their teachers. Not only did he build Buddhist temples and monasteries all around India, but he also established hospitals for both people and animals, and planted gardens. He even denounced war, asserting firmly that the only conquest left for him was the dharma, Buddhist teachings. Asoka’s story can be an inspiration to anyone on the wrong Path. Redemption is possible. Some historians believe that a third council was called by Asoka and took place around 237 B.C., at Pataliputra, lasting for nine months. Asoka donated funds to allow the Theravadins to write down the sutras and rules of the order for the first time. The sutras were grouped together in the Sutta-pitaka (sutra basket) and were actually kept in a basket at first. The rules of the Order were collected into the Vinaya-pitaka (ordinance basket). The commentaries written soon after Buddha’s death, explaining and developing his teachings, were called the Abhidharma-pitaka (treatise basket). The three baskets together were known as the Tipitaka, the Law Treasure of Buddhism. These texts, written in the Pali language, became the literature of early Buddhism, which included Theravada. They are considered the record of the teachings of Buddha and are the oldest written works of Buddhism. They are separate from the later Sanskrit writings of the Mahayana, done in the first century A.D.

Asoka sent missionaries throughout India and neighboring countries to convert people. Even his eldest son, Mahinda, was a devout Buddhist monk. King Asoka sent the prince and his disciples south to transmit Buddhism to Sri Lanka. Mahinda and eight other delegations spread Theravada Buddhism in the Pali language. It was widely accepted and spread to Burma, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia, where this form, Theravada (Hinayana) Buddhism, is still practiced widely today.

BUDDHISM OF THE ELDERS SPREADS

According to most accounts, the first country outside of India to receive Buddhism was Ceylon, now Sri Lanka. However, the Sinhalese chronicles and commentaries on the Pali scriptures, written by the ancient people of Ceylon, relate how Buddha personally traveled to Ceylon three times to give them the teachings directly. Early Burmese and Thai Buddhist writings also contain legends, much like the Sinhalese, that claimed Buddha had visited their countries. They believed some of the Indian Pali sutras secretly referred to people and places in Southeast Asia.

Despite these stories, historians believe the first contact with Buddhism came well after Buddha’s death, when King Devanamispiya was introduced to Buddhism by Asoka’s son (Lester 1973, 68). The Ceylonese king liked Buddhism so much that he built a monastery at the capital city, Anuradhapura, and established Theravada as the official form of Buddhism.

Later, King Asoka’s daughter, Sanghamittla, brought to Ceylon a branch from the original bodhi tree where Buddha attained enlightenment. With this important symbol of the Buddha himself, she founded an order of nuns that lasted for many centuries. However, nuns were given a lesser role in Southeast Asian Buddhism, and the order eventually died out.

Over the centuries, Buddhism enjoyed royal patronage. The sangha had a close relationship with the governments of Ceylon, Burma, and Thailand. This strong interdependency helped Theravada Buddhism, later renamed as Hinayana, to develop in new directions.

HINAYANA’S NEW ROLE FOR MONKS AND THE LAITY

The tradition that developed over the centuries altered Hinayana’s original narrow application as a philosophy only for monks. Hinayana became a large religion with a definite place for the general population. Monks continued to pursue the Path to become arhats. But a new way developed for people to practice Buddhism even if they stayed with their families, owned property, and pursued a career. Hinayana Buddhism guided the general public to live ethical, fulfilling, and happy lives with the promise that they would be reborn in a happier state in their next life.

Goals for the layperson were more modest than were the goals for the monks. First, just like the monks, people must sincerely follow the precepts not to kill, steal, be lustful, lie, or take intoxicants. They also were to take refuge in the Buddha, the dharma, and the sangha. Taking refuge in the Buddha meant they were to respect and revere Buddha as an enlightened guide to wisdom.

Taking refuge in the dharma involved learning about the teachings of Buddha, although laypersons did not go into as much detail as the monks. They did learn about mindfulness meditation and control of desires, but they followed these teachings more moderately. The monks taught people meditation and rituals that could set them on a gradual path to enlightenment. Once a week people went to the monastery to meditate and perform rituals that helped them become more alert and aware, calmer and happier. On this day they were to eat nothing after noon and wear simple clothes without any jewelry. They sat on the floor, refraining from the comforts of plush furniture or modern conveniences. In a moderate way, people learned to overcome their suffering by lessening desires and becoming more aware.

Taking refuge in the sangha involved helping the monks and the monastery with financial support. When people gave food and money, they earned merit toward a higher rebirth in their next life. Thus, laypersons were encouraged to work and accumulate wealth, so long as their work did not violate the precepts. Commensurate with the amount of wealth people acquired, they were expected to share some of it with the sangha, who relied entirely on the public for support.

Kings, like the common people, were expected to give generously to the sangha, building monasteries and donating financial support. In return, monks taught meditation to the kings and offered an enlightened perspective to help them rule wisely so that the kingdom could thrive.

The close relationship between the monastery and the government put new responsibilities on the monks. The rulers expected the monks to help the people by running Buddhist schools where children could learn reading and writing along with Buddhism. During the rainy season, when no farming could be done, sons were sent to the monastery to live as monks. They shaved their heads and wore the robes. Sometimes they even gave up their regular form of livelihood to join the sangha and become monks. Usually they returned home, but often enriched by the experience.

Hinayana Buddhism is still practiced in many Southeast Asian countries today, where centrally located monasteries are an important part of everyday life. But along the way, Buddhism’s path took a dramatic turn as the liberal form developed into Mahayana.

CHAPTER 3

The Blossom of Mahayana

What makes the limit of Nirvana

Is also then the limit of Samsara

Between the two we cannot find

The slightest shade of difference.

—Nagarjuna

BUDDHISM EVOLVES

At first, conservative and liberal interpretations were not fully opposed. The monks from both perspectives lived and taught side by side for close to four hundred years. Gradually, though, Buddhist doctrine began to change; by around A.D. 100, a new literature and a new rationale for the dissenting doctrine emerged.

This new literature revealed a doctrine that creatively reinterpreted the historical words of Buddha. Over time, these interpretations became more clearly defined, and sentiment grew among the liberal monks to make a formal separation from the conservative Elders.

The liberal groups proposed an explanation for how their ideas were authentic Buddhist doctrine. They said that while the Hinayana sutras were being codified at the First Council, another assembly of monks hid a number of new, more progressive sutras for safekeeping. Five centuries later, these hidden sutras were rediscovered and brought forth as the Mahayana scriptures.

Much like King Asoka, who championed the older form of Buddhism, King Kanishka (A.D. 78-103), a conqueror from northern India, helped to spread the new Buddhism with passionate zeal. He called a council of five hundred monks and collected their new texts into a group. They called their new form Mahayana, the Great Vehicle, formally separating from the traditional Buddhism of the Elders, naming the older group of Buddhists Hinayana, the Lesser Vehicle. Now Mahayana Buddhists distinguished themselves as their own separate form of Buddhism.

In northwestern and southern India, Buddhism was exposed to Hellenistic influences as well as Iranian and Mediterranean cultures. The more liberal and inclusive Mahayana was open to other cultures, helping it to spread to China, Japan, Tibet, Nepal, Mongolia, and Korea.

DOCTRINAL CHANGES FROM HINAYANA TO MAHAYANA

Mahayana Buddhists developed what they considered to be an expanded, superior, and higher doctrine than that of Hinayana. The new doctrine replaced Buddha as the center and originator of Buddhism with a wider conception of Buddha. In Mahayana, Buddha, temporarily incarnated in the earthly person of Siddhartha Gautama, became Dharmakaya, the embodiment of the dharma within a succession of Buddhas over the millennia, to be followed by other Buddhas in the future. Buddha became all Being, the meaning within all phenomena, now supernatural, timeless, and spaceless. Buddha could not be found in spoken words, doctrines, or learning. The dharma body, or Dharmakaya, was transcendent, and thus Buddha’s exact words and rules as memorized by Ananda and the early disciples were only a temporary embodiment, not the permanent one.

The bodhisattva replaced the arhat as the ideal role model. Bodhisattvas live with compassion, kindness, and patience. According to the Mahayana, wisdom is virtue, and thus being compassionate, kindly, and patient was the correct interpretation of the Buddha’s teaching, not that of becoming a wise, dispassionate arhat. Bodhisattvas did not withdraw from society to find nirvana. Their altruistic ethics encouraged good works in the interest of the whole world.

Mahayana added many long discourses on metaphysical subjects, replacing Buddha’s silence in the earlier sutras. Our experience of an apparently real world, Mahayana taught, is illusion. The true nature of reality is emptiness, which is explained in the next two sections on the Madhyamika and Yogacarin Sects of Mahayana Buddhism.

The highest value was placed on what the Mahayana called upaya, skill in means, which meant that there were many ways to reach salvation. This allowed for a much broader repertoire of theories, techniques, and methods that could be included in Mahayana Buddhism than had been allowed in Hinayana. For example, people were permitted to worship images of Buddha with rituals, thereby finding enlightenment with faith and not simply by wisdom as in Hinayana.

Mahayana tended to be more charitable and warmer than Hinayana. Practitioners could be more emotional, personal, and interactive with other people. They produced ornate art, literature, and ritual. Hinayana continued to be more monastic, secluded, conservative, and less emotional, viewing all passions as delusions.

Mahayana now could appeal to a larger variety of situations and people. They were less strict, more inclusive with regard to women and monks of lesser attainment, as well as opening the potential for enlightenment to householders.

TWO SCHOOLS OF MAHAYANA

Two major schools of Mahayana developed with their own doctrines, called Yogacara and Madhyamika. The Yogacarin philosophy, or mind-only school, believed that our minds create reality as we experience it. The other main root, Madhyamika or middle way school, held that we cannot ever know whether reality really exists. People should remain in the middle and take neither side. Mahayana doctrine became formalized as systems through these two schools. They would become the taproots for all later Mahayana forms of Buddhism that would be carried around the world.

NAGARJUNA AND THE MADHYAMIKA SCHOOL

Nagaljuna (b. A.D. 200) was an Indian philosopher who founded the Madhyamika school of Buddhism. Nagarjuna’s school taught philosophy as an alternative to meditation, for breaking the chains of becoming. Correct philosophical understanding is the approach to freedom from attachment, to find the Middle Way. Nagaljuna’s writings led away from idealist separation from the world, and away from classical disputes in philosophy. Nagaljuna offered an alternative to the two mainstream beliefs of his time, which were the oneness of the universe and the denial of the universe.

The Fourfold Negation Leads to Emptiness

Nagarjuna proposed a dialectic method of questioning called the Fourfold Negation. It consisted of four possible positions: (1) no position is tenable; (2) absolute versus relative existence accounts for the phenomena of existence; (3) the foundation for phenomena is emptiness; (4) codependent origination of phenomena accounts for the existence of phenomena. The Fourfold Negation can be restated as a logical paradigm, best shown in this chart:

Is

Is Not

Is

is, is

is, is not

Is Not

is not, is

is not, is not

Nagarjuna believed that concepts were inadequate to convey the essence of enlightenment, yet concepts were still essential—that is, concepts were both inadequate and essential. Paradoxically, all four combinations of is and is not are equally possible and impossible at the same time. Recognizing that all phenomena are interconnected, no philosophical position can be taken without being refutable. Nagarjuna showed how no philosophical position can be supported without question, without bias. No ultimate certainty exists. This leaves us with only one option: emptiness, which we cannot even call emptiness without error! Emptiness is the unifying basis for all philosophies, an ultimate ground that all philosophies share.

Nagarjuna’s critique of theories was neither conceptual nor cognitive because words and thoughts inevitably deceive us. Nagarjuna’s approach leads to giving up thought, letting go of conceptual boundaries and definitions, indeed, of existence or nonexistence itself. By the use of thought and logic, he leads the mind of his student to recognize the futility of thought and logic. If no basis for taking a philosophical position can be conclusively demonstrated, then why take one? Madhyamika is critical of all positions, including Hinayana. This opened the way for later developments in Mahayana.

VASUBANDU, ASANGA, AND THE YOGACARIN SCHOOL

The founders of the Yogacarin movement were two brothers, Vasubandu and Asanga. They lived in A.D. 400 in northwestern India. Asanga believed in Mahayana from the start. But his brother Vasubandu began as a Hinayanan. It was while translating some Hinayana texts that Vasubandu began to find fault. He then found new inspiration in Mahayana and became a spokesman with his brother for Yogacarin.

Both brothers believed that mind is the basis for enlightenment. The Yogacarin view of the world of phenomena is that it is all in our minds. Our thoughts make the world seem real. Yogacarins used meditation to reach a state of no-thought to escape the illusion.

Vasubandu also worked out an interesting new logic. He defined an existent thing by a specific example of what it is, what it does, and then he gave an illustration of what it is like and what it is not like. He always used specifics, never general or abstract categories. For example: (1) This fireplace has a fire in it (what it is); (2) because there is smoke, there is fire (what it does); (3) so it is a woodburning furnace (what it is like) and not a pond (what it is unlike).

This example reflects a Buddhist perspective of understanding each thing as it is in its particularity, not as a member of a class or category, as is done in Aristotelian logic. Lists of attributes are only temporary and relative. In Buddhism, abstraction is an illusion. Thus when we read Buddhist descriptions, it is puzzling from the Western perspective, where the class of something can help clarify a single individual case. From the Buddhist point of view, the class is empty, and the individual case is an example, an expression of the universal Buddha nature, which is empty of distinction. A form of logic known as Buddhist logic evolved the implications of Yogacarin further into a system.

PARAMARTHA: FINDING TRUE MIND

Paramartha (499-569) is one of the more renowned later Yogacarins who came from eastern India. He brought the school to China (A.D. 546) and translated seventy-five sutras and works of Yogacarins into Chinese. He was very outgoing and traveled around the country lecturing and teaching. As a result, he gathered many devoted students who carried forth the tradition.

One hundred years later, Hiuen-tsiang (650), who was taught by one of Paramartha’s students, taught Chi-k’uei (632-685), who brought Yogacara to Japan and called it the Hosso sect.

The essence of the doctrine is that defining things as real, separate objects in and of themselves is a phenomenon of consciousness. The world is an illusion, subjective—an extension of our inner conceptions. Perception can be tricked or distorted, as when we see a mirage or a conjuring illusion.

Paramartha believed that how we perceive, interpreted through language, sets up barriers to our understanding the world and the things that we are concerned about. In order to change behavior, we must change the meanings we give to things, including our dependence on language. Meaning is true essence, not the words we use. We must still the mind and withdraw from our sensory perception of the world in order to find the true Mind.

“Mind-only” is the “suchness” of an object, undifferentiated, in its true state. There are three ways to view an object. First is the imagined as real—simply itself, distinct from others. Second is the dependent aspect—how one thing is conditioned by other things. The third is that suchness or mind is the true essence of all things. In truth, there are no separate objects, and ultimately, even consciousness is illusion. Only mind exists. You can understand the truly real, or suchness, through meditation.

STOREHOUSE CONSCIOUSNESS

But the apparent constancy of phenomena and the world must be explained, and in fact was explained by the Yogacarins as alaya, the storehouse consciousness. Sense perceptions accumulate in a deeper core region of consciousness known as the storehouse, where they gather related perceptions, which, like a rolling snowball, produce other perceptions and conceptions that are drawn in and gather even more.

Storehouse consciousness permeates everything we experience in an all-pervasive way. For example, when you visit a clothing store, the clothes often have a perfumed smell characteristic of that store. While you are there, it affects your sense of smell. You bring an item home, and it maintains the odor for a while. The storehouse consciousness is similar, a heavy perfume that permeates everything we do and think all the time.

As a result of the storehouse consciousness, our actions, for good and bad, are affected. These actions, in turn, influence the world, which inevitably affects us, and more snowballing of perceptions and conceptions takes place. There is a feedback loop of mutual influencing, based on the storehouse consciousness. This gives constancy to our world, and makes it hard to change.

The storehouse consciousness can be dissolved by meditation. We learn to recognize the relativity of the world. Al is mind and mind is empty, without substance.

Illusion seems real, reality is illusion. Thus meditation shows the practitioner that though illusions seem real, nothing is real.

CONCLUSION

Yogacarins led their students deeply into illusion and then out of it to free them with meditation. Madhyamikans led their students with reason and philosophy and then freed them by showing them that reason and philosophy were futile. They were left with the middle way. Both schools were persuasive and effective in offering the Mahayana perspective. Each presented a part of the Mahayana whole. Subsequent development in Buddhism used their concepts as a springboard into emptiness, the foundation of Mahayana.

CHAPTER 4

Branching Out

Form is emptiness and emptiness is form.

—Heart Sutra

BUDDHISM IS TRANSLATED INTO CHINESE

Though India was the birthplace of Buddhism, China gave Buddhism a place to develop and grow. Sutra translators and traveling monks brought the doctrine from India to China and from there it spread to Korea. Korea introduced Buddhism to Japan in 552 during the reign of Emperor Kinmei. The rulers sought concepts, rules, rituals, and principles to guide and inspire their subjects, to create order and purpose, and to help develop their lands and people. Buddhism fulfilled these purposes. The leaders patronized monks and endorsed translation centers.

Kumarajiva (344-413) was a brilliant scholar and monk who facilitated the spread of Buddhism to the Chinese—in his case through his translations of the sutras. Kumarajiva headed an official translation bureau in China where he supervised a thousand monks in the translation of ninety-four works into Chinese for his royal patron, Yao Hsing.

Kumarajiva’s disciple Seng-Chao (374-414) was a student of Taoism before converting to Buddhism. He interpreted Madhyamika philosophy through Taoist lenses, and thus developed a clear and unique system of conceptualizing the inconceivable, to communicate Buddhism to the Chinese in familiar terms. Through Kumarajiva and his disciples, many Mahayana sutras were made understandable to the Chinese. Then he and his followers, especially Seng-Chao, skillfully rendered the Madhyamika and Yogacara sutras so that these ideas, too, could continue to grow.

NEW BRANCHES GROW

The Yogacara and Madhyamika schools may have been the solid tree trunk of Mahayana. But as Mahayana took root in other countries, it grew new branches.

The first branch produced two Chinese sects, T’ien-t’ai (Tendai, Japanese) and Hua-yen (Kegon, Japanese)—both systematically classified as Buddhism. These schools held that reality can be conceptualized in certain ways. T’ient’ai developed a comprehensive system to reunite thinking with enlightenment. Hua-yen’s grand scheme was based on intuitive sudden enlightenment over the use of reason.

A second branch produced Pure Land Buddhism, and the Japanese forms of Jodo and Shin. Pure Land made the chant the nembutsu, “Namu-amida-butsu,” which loosely translated means meditate on Amitabha Buddha, into a sacred action.

According to the third branch, reality is unspeakable, unthinkable: All theories are false. Some Mahayana Buddhist sects, such as Zen, follow this tradition. Words, concepts, and theories, at best, only point toward the truth, but language cannot express it. Ludwig Wittgenstein, a renown European philosopher, stated it well: “Beyond this is silence.”

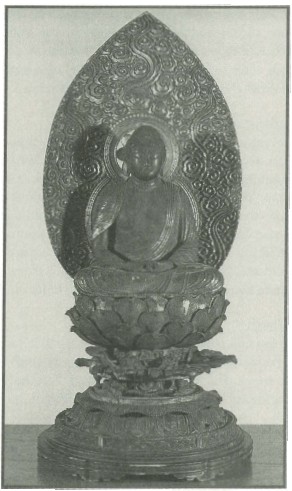

Amida Buddha, the bodhisattva Amitabha. Japan, Early Edo Period, Wood, seventeenth century. Bequest of Mrs. Cora Timken Burnett, San Diego Museum of Art

A fourth branch rejected the direct use of reasoning to lead to truth in favor of other ways, such as mandalas and mantras. Tibetan Buddhism and other Tantric sects such as Shingon follow this mystical path, using elaborate visualizations and rituals as the means to enlightenment. (These forms will be developed in Simple Tibetan Buddhism, another book in this series.)

T’IEN-T’ AI BUDDHISM

T’ien-t’ai began in China and was named after the mountain monastery where the master resided. Chih-i (538-597) is considered the founder of T’ien-t’ai. Although he was not its originator, he wrote, organized, and developed the concepts his teacher helped him to realize. Chih-i’s formulations became the means of conceptualizing T’ien-t’ai’s vision of Buddhism. He instituted concepts to systematize and incorporate the varieties of Buddhist doctrine into a unified, rational hierarchy. Each was given a place and a category.

T’ien-t’ai did not blend and synthesize all of Buddhism as one. Each retained its separate identity as a reflection of the whole.

The Threefold Truth

The threefold truth is the basic statement of the T’ien-t’ai doctrine. The first truth is that the world we think of as real is actually an illusion. We believe it is real because we experience it, but it is not real. The experienced world is empty of any lasting substance; it is transitory, an illusion given to us by our senses and mind.

The second truth is that this world of experience has a temporary existence. It is only partially or temporarily real. Things are real for now, due to their apparent, momentary existence. The second truth says we cannot say that nothing is present at all, for if we do, how could the senses and mind perceive things? Reality is fleeting, like a flash of light, but the flash does happen.

The third truth says there is something, but then asks what is it? It is not “nothing,” but neither is it “something.” A middle path emerges from the interaction between, a synthesis that includes them but also transcends them. This third truth is a mysterious fusion, so there is no distinction possible. Absolute mind is completely integrated with the universe. Everything is a function of the true state.

Suchness: The Ultimate Unity

At the highest level of understanding, in a grand synthesis, all are present in one thought. This one thought is what the T’ien-t’ai calls Suchness, the ultimate category. Everything is just as it is.

For example, consider the common food product butter. Different kinds of butter vary in their subtle flavors, depending upon the brand, whether salt has been added, and how it is manufactured. But in its essence, all forms are still butter. Different flavors might taste differently to different people, but ultimately all butter is of the same essence.

This world is real. There is no other. The phenomena we see and experience are a function of their conditions, causes and effects, nature, and substance, which are intimately interrelated with the inner truth of the universe.

Whether we look at the world from the absolute (nirvana) or the relative (samsara) frame of reference, it is the same at its inner core yet different in its outer expression. The core is empty. Like a doughnut, whose nature depends on the hole, both dough and hole are necessary: No whole without the hole. Similar to physics’ modern theory of matter, nothing is constant; everything is always changing. Yet the central nothingness within everything is eternal and shared by all.

In the absolute sense, everything and everyone is of one root, one essence. Boundaries are only relative, depending on your point of view, always changing. When we can experience this, we can accept that things are just as they appear. We feel the interconnectedness of all reality and live our lives accordingly, in harmony, which is the true nature of reality.

The Five Periods

As the Chinese became more knowledgeable about Buddhism, they began arranging, classifying, and systematizing sutras and doctrines. Students of Buddhism questioned how it was possible that one individual (Buddha) could have taught so many sutras, so widely, with so many apparent contradictions and inconsistencies. T’ien t’ai explained it by dividing Buddha’s teachings into five periods and eight methods.

The first period was the Hua-yen or Avatamsaka. Immediately following his enlightenment (528 B.C.), Buddha attempted to express the wisdom through the Avatamsaka Sutra. But the understandings were too advanced, and so he saved this sutra for later. The second period included the early scriptures and the Four Noble Truths that made up the Pali Canon of Hinayana Buddhism (528-200 B.C.). During the third period (200 B.C.-A.D. 100), the basic Mahayana sutras introduced the new concepts of Mahayana Buddhism. The Prajnaparamita Sutras of Perfect Wisdom were the fourth period (A.D. 100-200), with the concept of emptiness and no distinctions between doctrines. The fifth period (A.D. 200-600) presented the Lotus Sutra, with its comprehensive unity of all teachings. T’ien-t’ai believed this period represented the most profound level of understanding.

The Eight Methods

The wisdom from each period was communicated using four teaching methods and four sets of texts. The Four Methods were Sudden Enlightenment, the most sophisticated; Gradual Enlightenment, using step-by-step Vipassana insight meditation; Secret Doctrine, incorporating rituals and mysticism; and the Indeterminate, an indirect, subtle way of teaching. In the fourth method, all students thought they were being spoken to and personally addressed by the Buddha, indirectly, through symbols, gestures, and teachings.

The doctrines included many collections of Buddhist texts. First were the early procedures laid out in the Tipitaka. The Shared Doctrine, used by both Hinayana and Mahayana Buddhists was next. The Distinctive Doctrine explained about becoming a bodhisattva, and the Complete Doctrine, from the Lotus Sutra, gave the dimensions of practice for Buddhahood, where everything is unified—all things are contained in each individual thing.

The Five Periods and Eight Methods showed how all of Buddha’s teachings from different times and places could be true. Buddha had used different approaches to teach people at varying levels of sophistication. T’ien-t’ai welcomed all the teachings as a diverse resource from which the students could draw, depending on their talents, capacities, and needs.

T’ien-t’ai’s clear and exacting formulations were used to teach Chinese Buddhism for many centuries. Later, T’ien-t’ai was brought to Japan and became known as Tendai Buddhism. Tendai Buddhism had a long and influential effect on Japan.

HUA-YEN: ONE IN ALL PHILOSOPHY

Hua-yen Buddhism arose in the seventh and eighth centuries. Fa-Tsang (643-712) is usually considered the founder, due in part to the volume of his writings. He is said to have written over one hundred works. He systematized and created a coherent, orderly philosophy under the patronage of Empress Wu. He was also a dynamic speaker who could move audiences with his words. According to legend, once, after delivering a dynamic lecture, the earth shook! His most popular writing was the Commentary on the Heart Sutra, still read today by practitioners from differing sects.

Weaving the flowers of Mahayana into a beautiful garland, the works of Fa-Tsang and the other great thinkers in the lineage helped to communicate this form of Buddhism. Eventually, Hua-yen was brought to Japan where it became known as Kegon.

The Great Unification

There were three important principles in Hua-yen. The first principle, Realms of the Whole, was a unique contribution that allowed Hua-yen to be inclusive. Hua-yen made sense of the varied sects, synthesizing them together into one whole. On the surface, the many varied teachings of Buddha might seem different, but in their essence, they are all the same. Each sect actually presents only one view of the larger panorama, the realm of dharmadhatu.

Emptiness, the second principle, was central to all Mahayana sects. But Huayen doctrine included form within the formlessness. Emptiness was expressed in terms of its relation to fullness. Everything, each individual object, is both mirror and reflection, reflecting all other objects, and in turn, only the reflection in another mirror from another perspective. For example, the parts of an automobile gain their meaning united as a car, but are not, in themselves, a car. In the same way, the individual parts of the universe gain their essential meaning from the universe as part of the whole.

A calm lake quietly reflects the surroundings. In perfect stillness, which is the true image and which the reflection? Without a calm lake, no image of the surroundings can be reflected. Without the surroundings, there could be no reflection in the calm lake. They come into existence together in a flash.

A person sees the lake and the reflection as an experience. The perception takes place by means of the mind of the person viewing it. Therefore, is the perception only in the mind, or is it more than mind?

The third principle is Totality, mutual interdependent interaction among everything. Hua-yen included reality and substance as part of the totality, the whole. Hua-yen reintroduced logic and reason as part of the enlightened reality, essential within the grand synthesis of all that is. It all depends on your point of view, your level or realm of understanding, and your frame of reference. Therefore, Hua-yen was a round doctrine, without an edge or boundary. Each part complemented the other. No one part was complete without the other. Hua-yen’s perspective was not one-sided.

Each had its place, its part. Hua-yen’s realm is a totality, an integrated organic whole. It was an affirming, positive philosophy that included everything as threads in the tapestry of enlightenment. There is no obstruction since everything has mutual interpenetration and mutual identity, fused in the oneness of the dharmadhatu.

Although details may vary and emphases may differ, the essence, the central principle within all systems, was identical according to Hua-yen.

PURE LAND: THE EASY PATH

Pure Land Buddhism was a Mahayana sect that evolved gradually, beginning formally in China. Inspiration came from India, from sutras composed about three hundred years after the death of Buddha called the Pure Land Sutras.

The school that developed in China was led by Hui-yuan (336-416), who founded the White Lotus Society, named after a lotus-covered pond near his monastery. It was this society that became the basis for the Pure Land sect in China. They retired from society to seek seclusion and live according to the dharma. The teachings from the Pure Land perspective spread throughout other sects in China. In Japan, the ideas were organized and codified by Honen (1133-1212) into Jodo Buddhism, which arose in reaction to the often demanding efforts required for Buddhist practice.

Honen was a charismatic, warm, and inclusive man who had a deep desire to attain enlightenment. Yet he found it too difficult to practice the three disciplines of precepts, meditation, and knowledge on his own. One day Honen came across writings from the Pure Land sect that taught the use of the nembutsu. Honen was overjoyed, for here was an easy way to enlightenment.

The Pure Land adherents believed that Buddha’s enlightenment was timeless and spaceless, beyond the confines of his life. Enlightenment is personified as many Buddhas and bodhisattvas. The loving bodhisattva Amitabha vowed that he would refuse to be fully enlightened until all entered into nirvana. This vow committed him to altruistic and selfless devotion to others, permitting anyone to gain from him. Amitabha’s great sacrifice of his own personal nirvana was for others. The merit of a positive action can be transferred to another instead of being used by the person who earned it. Therefore, Amitabha could save anyone through transferring his merit. By sincerely calling his name, saying the nembutsu “Namu-amida-butsu,” he opens his paradise to anyone.

Pure Land puts faith in the power of Amitabha. Faith in “other power,” joriki, is the preferred path of Pure Land practitioners rather than faith in one’s “own power,” tariki. Joriki is an alternative to striving by your own efforts to reach enlightenment.

Honen’s student Shinran (1173-1262) developed his own sect, known as Jodo-Shin or Shin Buddhism. One of Shinran’s students evolved the Pure Land doctrine of nembutsu’s power to be even more pure, a complete self-contained practice that guaranteed enlightenment if wholeheartedly performed even once.

Though Honen and Shinran exclusively focused on the nembutsu as all that was necessary, followers later modified the doctrine to permit involvement in Buddhism’s other practices. Many of the sects of Buddhism have now included aspects of this doctrine—especially the chanting of the nembutsu and faith in the bodhisattva ideal as personified in Amitabha—as adjuncts to Mahayana practice.

Everyone who practices, whatever their situation, may be reborn in the Buddhist paradise. This easy way to achieve peace and enlightenment is inclusive and positive toward all. No one is excluded, regardless of former misconduct, weakness, or deficit, if they faithfully practice Amitabha’s vow.

This complete faith was so simple and dramatically powerful that it appealed to many. Even though Honen himself emphatically declared that nembutsu was not a form of meditation, others used it as a meditation and still do.

The Pure Land is a sentiment within the heart of Buddhist doctrine. In a sense, we are all in the Pure Land, here and now. This is our paradise if we let it become paradise.

ZEN BUDDHISM

Buddha held up a flower at Vulture Peak and smiled, communicating the spirit of enlightenment. All the monks sat solemnly, watching Buddha. Only Mahakasyapa understood, and smiled. This was the first recorded direct transmission of enlightenment, from mind to mind, without words. Zen began at this moment. Zen tradition carried the experience of enlightenment forward through twenty-eight patriarchs in India to Bodhidharma, who transmitted Zen to China. This tradition of transmitting enlightenment without using words, mind to mind, is the cornerstone of Zen and continues to the present day.

Since Zen’s doctrine emphasizes the essence within sutras and rituals of Buddhism, Zen has in whole or part been integrated with many other philosophies, religions, and activities, including art, martial arts, psychotherapy, and Christianity, among others. Our books, Simple Zen and Zen Around the World describe the Zen way in detail.

TRANSMISSION FROM BODHIDHARMA TO THE WORLD

Bodhidharma (440-528) traveled to China, taught monks to meditate, and also taught them martial arts to help them actively learn. Bodhidharma believed that the elaborate rituals and doctrines in Buddhism were a distraction that prevented people from recognizing that their own nature here and now is enlightenment. “To find a buddha,” he said, “you have to see your nature. . . . If you don’t see your nature, invoking buddhas, reciting sutras, making offerings, and keeping precepts are all useless” (Pine 1989, 11).

Hui-neng (638-713) changed Zen by emphasizing the idea of sudden enlightenment. He is considered the founder of modern Zen. Since our mind is the buddha, we are already enlightened. There is nothing to seek, nothing to find. Meditation can help you realize this, but doing anything with intensity will have the same result. Walking, eating, sleeping—all are opportunities to practice Zen. The practice of enlightenment is interpreted in many ways, but the core, according to Zen, is meditation.

Zen evolved into various schools and branches, Soto and Rinzai in Japan, known as the Tsao-Tung and the Lin-chi lines in China, were most significant. They had different emphases, yet both carry the spirit of Zen. Soto focused on practicing clear-minded meditation, zazen. These practitioners deemphasized enlightenment in favor of the practice of meditation itself. They believed practice is inseparable from enlightenment rather than a path leading to it.

The Rinzai approach fervently strove for enlightenment and continually sought to deepen the experience through the practice of meditation on koans, stories from Zen masters that portray the enlightened mind in teaching situations.

Koans, zazen, and Zen arts evoke the open-minded inclusive awareness characteristic of Zen Buddhism. But paradoxically, in Zen, not one sutra or koan explicitly describes enlightenment, yet all illustrate it through the ultimate fusion of enlightenment with everyday life.

CHAPTER 5

Flowers from Buddha’s Garden

The world is the movie of what everything is, it is one movie, made of the same stuff throughout, belonging to nobody, which is what everything is.

—Jack Kerouac, Scripture of the Golden Eternity

There is a vast collection of literature that conveys the ideas and points to the experience of Buddhist enlightenment. Those that express the words of the Buddha have been collected into two separate groups: the Hinayana Pali sutras and the Mahayana Sanskrit sutras.

HINAYANA SUTRAS

The early sutras express Buddhist concepts through stories, analogies, and lectures. They portrayed the teacher, Buddha, guiding people with real-life problems and questions. These sutras expressed Buddha’s ideas about impermanence, reducing desires, and developing wisdom. Throughout, they encouraged people to take the moral path to find enlightenment.

Mustard Seed Sutra

One of the most well-known sutras, the Mustard Seed Sutra explains the very difficult philosophical concept of impermanence through a story. A mother named Kisa Gotami was grief-stricken when her young son died in childhood. Rather than face the tragedy, she carried the dead child from door to door seeking medicine to cure him. People laughed at her for trying to find a treatment for death, but one person took pity and told her to go see Buddha. Filled with hope, she quickly sought out Buddha. The Buddha could see that in order for Kisa Gotami to accept what had happened, she needed to understand impermanence. “Go and find grains of mustard seeds,” he told her, “but only from a household where no one has ever died.”

She agreed and set off to find the cure she sought. But every house she visited had the same answer: Someone in the family, either a child, parent, or grandparent, had died. Gradually she began to realize the sad truth: For all people in the world, all things are impermanent.

The Dhammapada

The concepts of Buddhism were expressed in many sutras. As more and more people wanted to learn about Buddhism, teachers gathered the insights together into a single teaching sutra that expressed the essentials. The Dharmapada (Sanskrit) brought many lessons together by theme into one sutra. The words were ascribed to Buddha, taken directly from his many sermons. There were a number of different versions of the Dharmapada, depending upon which sect collected them, but the same ideas were common to all.

The Dharmapada emphasizes that the only path away from suffering and toward happiness is through personal efforts. “Rouse thyself by thyself, examine thyself by thyself, (Yutang 1942, 322).

Buddha’s argument to stop doing what you should not and do what you should was not based just on moral grounds, it was also pragmatic. He believed that wrongdoing brings suffering and discomfort to the doer. “Fools of poor understanding have themselves for their greatest enemies, for they do evil deeds which bear bitter fruits” (Yutang 1942, 331).

Buddha did not simply ask people to stop engaging in negative conduct, he urged them to engage in conduct that was positive. Acting with love and compassion brings true happiness and fulfillment. Most of us are well-intentioned, but we find it difficult to follow through. Buddha provided a method to tame the mind and take control of action by awakening to enlightenment. With this awakening comes the happiness of nirvana.

BUDDHA’S FAREWELL SERMON

As Buddha felt himself slipping into death, he exerted a strong effort and brought himself back long enough to speak to his students. “I am old now,” he told them. “My journey is ending. But even though my body ceases to be, you have what you need within.” His most famous words were “Be a lamp unto yourselves . . . seek salvation alone in the truth” (Burtt 1955, 49). Thus, in this sutra, Buddha left his disciples with the wisdom of Buddhism. Salvation comes from delving deeply into your own awareness, exploring your thoughts, feelings, and sensations. Only by holding steadfastly to the light of truth shed by your own lamp can you end suffering to find peace and happiness.

MAHAYANA SUTRAS

Mahayana Sutras reflect improvements, developments, and insights from Buddhist practice: wordless insight of enlightenment, the bodhisattvas ideal, ultimate emptiness, interpenetration of all things, and faith.

These works, like all sutras, were written as the words of the Buddha. The Mahayana legend was that immediately following Buddha’s enlightenment, he preached the doctrines of these sutras. However, no one could understand the message. So he decided to begin with a simpler doctrine and save the deeper sutras for later, when people would be better able to receive more sophisticated teachings. Thus, the Hinayana sutras were taught in order to prepare Buddha’s followers for Mahayana.

Perfect Wisdom Sutras

The group of teachings, known as the Prajnaparamita, Perfect Wisdom Sutras, marks the new path of Mahayana. Perfect wisdom is not easy to grasp. It lies beyond descriptions and cannot be thought about. “Where there is no perception, appellation, conception, or conventional expression, there one speaks of ‘perfect wisdom’” (Conze 1995a, 150).

Perfect wisdom is quiet, empty, goal-less, and nonexistent. This definition might seem contrary to the usual conception of wisdom in our fact-hungry, data-crunching world. But the sutras explain how the enlightened perspective has a calling beyond everyday concerns, though affecting them.

The Heart Sutra, one of the most famous sutras of the Prajnaparamita, describes the relationship between emptiness and everything in our world. The sutra states that form is emptiness and emptiness is form. Everything we know and experience in the world is without lasting substance even though it exists to us in the moment of experience. When we accept ultimate emptiness and grasp the transitory nature of our existence, we comprehend the Buddhist logic of freedom. Most Zen sects chant the words of the Heart Sutra daily to help clear their minds of thought, opening the way to enlightenment.

The Diamond Sutra (Diamond Cutter) is another key sutra in the Prajnaparamita. A diamond is the hardest stone and can cut through all others, but when polished, it shines brilliantly. Like the diamond, this sutra cuts away our limited, small-minded, everyday perspective and allows us to discover a shining light—the all-encompassing wisdom of enlightenment. As Saint Paul said, “The things that are seen are temporal; the things that are unseen are eternal” (Price and Wong 1990, 5).

The Diamond Sutra makes a number of points that seem paradoxical at first, such as enlightenment is perfect wisdom. It states that there is nothing to attain and nothing to grasp, but that we must devote ourselves to trying to attain and grasp it. If we are to experience enlightenment, the sutra says we must develop “A pure, lucid mind, not depending upon sound, flavor, touch, odor, or any quality . . . a mind that alights upon nothing whatsoever” (Price and Wong 1990, 28). If nothing is there, how can wisdom be grasped? Wisdom is not found in objects of any kind, neither in the outer world nor of thought itself. People should recognize this truth and reject illusion. We should look for the enlightened truth of perfect wisdom in going about our lives with a clear, calm mind.

Avatamsaka Sutra

The Avatamsaka Sutra (Hua-yen) is another large collection of sutras that were embraced and developed by the Hua-yen school in China between the first and fourth centuries. The name “Avatamsaka” means “garland” or “wreath,” and this collection is sometimes referred to as the Flower Garland Sutra. It is known to us through Chinese translations ranging in size from forty to eighty parts of 30,000 lines total. The sixty-book translation done by Buddhabhadra (418-421) was used by the Hua-yen school to guide their path.

The Avatamsaka Sutra combines the understandings from the two earlier Mahayana schools: Madhyamika and Yogacarin. From Madhyamika, the sutra embraced emptiness as the ultimate nature of all things. From Yogacarin, it adopted the mind-only perspective that all being is illusion.

Integration, known as the “All in one and one in all” doctrine, is a unique contribution of this sutra. All things contain reflections of everything else, nothing exists without background and boundaries. So on the absolute level there is no distinct separation between things. Thus there is no separation between all that we actually experience in everyday life and transcendent enlightenment. Each thing relates with everything else. They coexist, all merge into one. This idea was difficult for people to understand. Fa-Tsang, the most important patriarch of Hua-yen, used an ingenious demonstration to explain the theory to Empress Wu, a great patron of Buddhism. One day, the empress said to Fa-Tsang, “I am struggling with the idea of totality. Sometimes I feel as if I almost grasp it, but then other times I’m not sure again. Can you give me a clear illustration?” Fa-Tsang promised he would.

A few days later he returned and said, “Your demonstration is ready. Follow me? He led her to a small room where he had attached mirrors to the floor, ceiling, and all four walls. While she was watching, he placed a statue of Buddha at the center. Suddenly, the empress could see Buddhas appear, infinitely reflected in every direction. “How marvelous!” she exclaimed, as the concepts became real for her. She could literally see how all was reflected in everything else, all exhibiting Buddha everywhere. She could also see how things were codependent, all coming into being simultaneously at the moment that Fa-Tsang placed the statue down on the floor in the middle of the room of mirrors.

The Avatamsaka Sutra illustrates in many forms how all beings, objects, moments, and places merge, uniting with one another while retaining individuality, in emptiness.

Vimalakirti Sutra

The Vimalakirti is one of the most popular Mahayana sutras. Based on the insights of a wealthy businessman named Vimalakirti, who attained Buddhist enlightenment, this sutra shows how anyone can be enlightened. A person did not have to give up his everyday life and become a monk, as the earlier doctrine required.

Vimalakirti was a living example of this. His successful career showed how a person could express the silence of enlightenment even in the midst of activity, that meditation was not something separate. As he explained to Sariputra, one of the monks of Buddha’s inner circle, “To sit is not necessarily to meditate. . . . Not to abandon the way of the teaching and yet to go about one’s business as usual in the world, that is meditation” (Dumoulin 1988, 50).

Awakened living is what Vimalakirti urged. People do not have to avoid problems or challenges; from an enlightened perspective, difficulties do not have to cause anxiety and suffering. “Not to cut [off] disturbances and yet to enter nirvana, that is meditation” (Dumoulin 1988, 51). Sitting quietly in meditation to empty the mind of all disturbances is unnecessary. Enlightenment is a part of everyday life.

The Vimalakirti Sutra illustrates how enlightenment is both filled with potential and yet empty. One day, Vimalakirti went to bed, sick. A large assembly of Buddhist monks were planning to visit him. Sariputra, who had arrived early, asked Vimalakirti, “How can this small room possibly accommodate all the hosts of monks who want to visit you?”

Vimalakirti answered, “Are you here to seek chairs or Dharma?” (D. T. Suzuki 1978, 99). The sutra goes on to say that one hundred thousand celestial chairs were brought in, and when all the thousands had assembled, it was not at all crowded. Vimalakirti explained that such a miracle was possible because enlightenment is filled with potential, unbounded by space and time.

When Manjusri, the bodhisattva of wisdom, arrived at Vimalakirti’s bedside along with the group of bodhisattvas, he asked them all, “What does nonduality mean?”

Each in turn stepped forward to offer intellectual explanations. One said that nonduality was the resolution of opposites. Another claimed it was purity versus impurity. Finally, Vimalakirti was asked to give his insights on the subject. In response,Vimalakirti sat silently. Manjursi applauded the answer. “Well done, well done,” he said. “Ultimately not to have any letters or words, this is indeed to enter into the doctrine of nonduality” (Ch’en 1973, 384). Zen Buddhism followed this emphasis on wordless, unspeakable, indescribable enlightenment. Silence can be a path to follow. The sutra encourages stillness in one’s house. Everyday life flows from this enlightened silence, bringing happiness and fulfillment.

Lankavatara Sutra

The Lankavatara Sutra is one of the most psychological of Mahayana sutras. Originating around the second or third century A.D., this sutra was basic to Yogacara. It describes the mental changes that take place as an individual travels the path to enlightenment. One of the key points is that enlightenment comes when a person realizes how his or her mind influences perception. At that point, the person sees through illusion.

The following parable from the sutra illustrates this idea. King Ravana asked the bodhisattva Mahamati to explain Buddha’s enlightenment experience. Suddenly, the king noticed that his home was ornately decorated. Then it seemed to multiply into infinite numbers of lavishly decorated palaces with Mahamati sitting in front of each one asking Buddha to describe his inner experience. Next, the king heard one hundred thousand delicate voices answering. Then, as suddenly as it appeared, the entire scene vanished, and the king found himself standing alone in his palace. Confused, he said, “Am I dreaming?”Then he realized that just like the images he had imagined, everything is a creation of the mind. Upon that thought he seemed to hear voices say, “Well you have reflected Oh king! You should conduct yourself according to this view” (D.T. Suzuki 1978, 101).

Meditation is recommended to help people clear their consciousness of illusions. The sutra describes four dhyanas (meditations) to take the practitioner from beginning mental skills to fully enlightened self-realization. Through these meditations, a change in thinking takes place until illusion dispels and enlightenment develops.

Lotus Sutra

The Lotus of the Good Law (Saddharmapundarika), one of the central sutras for the T’ien-t’ai school in China and Tendai and Nichirin schools of Japan, was composed around the first century A.D. This sutra vividly portrays the Mahayana conception of the Buddha, who is described as more than the mortal man Gautama Siddhartha, who found enlightenment; Buddha is the living expression of all enlightened beings, from infinite time—past, present, and future.

The sutra begins on Vulture Peak where Buddha meditates. He is surrounded by many gods, people, and bodhisattvas. The peak is illuminated by rays emanating from Buddha, and the hillside is strewn with beautiful flowers. This scene paints a new picture of Buddha, as an all-wise being with great powers and vision. Buddhist artists often used this sutra as inspiration. The sutra clearly describes Buddha’s new status: “The true Tathagata, the embodiment of cosmic truth, neither is born nor dies, but lives and works from eternity to eternity” (Ch’ en 1973, 380).

Skillful Means

The sutra explains why Buddhism seems to offer many different ways to find enlightenment through the concept of skillful means. When Buddha was teaching, he always tried to make each lesson relevant to the student. He recognized that people differ in their personalities, needs, motivations, and intelligence. Thus his lessons could sound very different, depending on whom he was teaching. This parable was included in the sutra to illustrate skillful means.

A father stood outside his home watching in horror as it became engulfed in flames. He knew that his three young children were playing happily inside, but realized that there was not enough time for him to run inside and carry each one out. The only way to save them all was to get them to come out themselves. Knowing how much they loved carts, he called to them, “Children, come quickly. I have a beautiful cart outside for each of you. Come see!”The children ran out laughing, full of excitement to see the pretty carts. The father did have some carts to give them, so each child was not only saved but also happy. Like the father, Buddha promises something to motivate everyone to let go of a limited perspective and seek enlightenment.