The movie lover’s Midtown Manhattan represents New York at its busiest, its most intense, its most exciting. This is the New York of landmark skyscrapers, legendary department stores, historic grand hotels, glamorous restaurants and nightclubs. Possibly the only place on earth with so much power, energy, and screen appeal concentrated in such a small space, Midtown is ultimately the hunk of New York that many people think of as “New York.” One of the reasons that the images of Midtown are so powerfully embedded in our collective consciousness may well be because the area has been immortalized by so many films—especially films made in Hollywood, which needed only the right music and a couple of dramatic process shots of the Empire State Building or Rockefeller Center to establish their New York settings. Herewith, then, a look at this awesome part of town—focusing both on its screen presence over the years as well as on the dynamic (and occasionally scandalous!) roles that many of its famed hotels, restaurants, clubs, and office towers have played in the lives of the movers and shakers of the motion picture business. For the movie lover, indeed for the rest of the world, Midtown is not only archetypal New York, it’s the center of the earth.

One of the greatest things about film is the way it can document certain landmarks for all time. A case in point is New York City’s original Pennsylvania Station, a grand colonnaded Roman temple of a building—actually modeled on Rome’s Baths of Caracalla—that was equally impressive inside with its spectacular waiting room and iron-and-glass train shed. Built in 1910, the station bit the dust in 1963, to be replaced by a massive but not terribly exciting modern hulk that combined an office tower, Madison Square Garden, and a low-ceilinged subterranean train station. So to check out the original, it’s necessary to check out a few videos or DVDs. Start with Applause, a 1929 early talkie made in New York by director Rouben Mamoulian and starring the legendary torch singer Helen Morgan as an aging vaudevillian. In the Penn Station sequence Morgan meets her daughter, whom she’s shipped off to a convent to spare her the realities of her tough showbiz life, amid crowds of commuters. Fast-forward to 1945 and Vincente Minnelli’s The Clock, in which his then wife Judy Garland meets and falls for a soldier on a forty-eight-hour leave (Robert Walker) at Penn Station, where Walker rescues Garland’s shoe, which has gotten caught in an escalator. Although the station scene is highly realistic, Minnelli had the capable MGM art department do up the whole thing in Culver City. But for Hitchcock’s 1951 adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s novel Strangers on a Train, the director used the real station for a scene that has police following Farley Granger, who’s the prime suspect in the murder of his estranged wife, which was actually committed by a stranger (Robert Walker) he met on a train. Penn Station was also one of the New York locations used by director Billy Wilder for the infamous The Seven Year Itch (1957), which starred Marilyn Monroe. The opening shot of the film shows Penn Station in all its skylit glory at rush hour on a hot summer day, as Tom Ewell puts his family on a train to Maine. Ewell will stay behind in Manhattan and return to his apartment to find Marilyn as his new neighbor.

As for the current Penn Station, it has made relatively few screen appearances, since New York boasts a much more popular and spectacular train-station location in Grand Central. Still, movie lovers can catch today’s Penn Station in Clockers (1995), Hurricane Streets (1997), and A Perfect Murder (1998). In the last, Viggo Mortensen tries to escape with $400,000 on an Amtrak overnighter to Montreal. A maniacal Michael Douglas foils his plan, however.

Meanwhile, there have been plans for a third Penn Station to rise within what was the former U.S. Post Office Building. Standing directly across Eighth Avenue from the current Penn Station/Madison Square Garden, the old post office structure is another neoclassical affair with an enormous staircase leading to a colonnaded arcade. It went up in 1913, four years after the original Penn Station, and was designed in the image of its neighbor. Thus, should it ever open as a train station, New York’s new Penn Station will look and feel much more like the original. Good news for travelers, filmmakers, and movie lovers.

“The world’s largest store” boasts over 2 million square feet of floor space and reportedly employs as many as ten thousand salespeople! For the movie lover, the significance of Macy’s has less to do with retailing statistics than with a very important event that took place over a century ago in the building that once stood on the mammoth department store’s Herald Square site. That building—demolished at the beginning of the twentieth century to make way for Macy’s—was a theater called Koster and Bials Music Hall, and it was there that, on April 23, 1896, Thomas Edison publicly unveiled the Vitascope, a magical machine that projected lifelike moving images on a twenty-foot screen set in a huge gilded frame. There were many oohs and aahs at Koster and Bials that famous evening as the audience saw a group of seconds-long snippets of such things as a prizefight, dancing girls, and “Venice, showing gondolas.” One of these little films, titled Sea Waves, depicted rough surf and crashing breakers and is said to have caused a bit of a stir among the spectators in the front rows. The magic, and ultimately the power, of motion pictures was clear right from the start.

About ten years after the debut of motion pictures on the Macy’s site, Edison’s top director, Edwin S. Porter, shot an important early story film using the newly erected department store as a location. The film, titled Kleptomaniacs, told the parallel stories of two women, one rich, the other poor, who get caught shoplifting at a big department store—and pointed out the disparities between the ways society treats the rich and the poor. The wealthy woman is let off and considered an unfortunate victim of kleptomania, whereas the other woman is arrested and ruthlessly hauled off to jail. Clearly, the movies had come a long way in ten years.

Forty years after Kleptomaniacs, Macy’s had come a long way, too, when it was given a starring role in Twentieth Century–Fox’s 1947 Christmas classic, Miracle on 34th Street, which pits an eccentric Macy’s Santa Claus against a bah-humbug toy department head. Besides a number of exteriors shot at Macy’s, the film also includes footage of the store’s famed once-a-year media event, the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. The parade turned up again in the lackluster 1994 remake of Miracle, which although still set in New York, was shot largely in Chicago. Since Macy’s refused to be associated with the remake, the store’s name was changed to the fictitious CF Cole’s, with Chicago’s famous Art Institute serving as the faux store’s exterior.

Back in Manhattan, other films that have immortalized the real Macy’s have been the George Cukor–directed made–in–New York screwball comedy It Should Happen to You (1954), where a newly famous Judy Holliday is mobbed by autograph hounds while shopping for sheets; Auntie Mame (1958), which finds Rosalind Russell, as the madcap Mame, trying to sell roller skates at Macy’s at Christmastime; Love with the Proper Stranger (1963), where Natalie Wood works in the pet department and where her love Steve McQueen draws quite a crowd outside the store when he plays bagpipes at the end of the film wearing a “Better Wed Than Dead” sign; The Group (1966), in which Kay Strong, played by Joanna Pettet, rises up the retail ladder as a Macy’s executive, only to find that corporate success doesn’t necessarily mean happiness; and Radio Days (1987), where Little Joe (who grows up to be Woody Allen) is treated to a chemistry set in the toy department in the 1940s.

Of all New York’s landmarks, none is as closely associated in the popular imagination with one single film as is the Empire State Building with the legendary monster movie King Kong. When RKO released the picture in 1933, the Empire State Building was barely two years old, but it had already made history as the world’s tallest building. Soaring 1,250 feet into the air, this sleek sandstone-and-steel structure stunned the world with its 102 stories, 87 elevators, 2 observation decks, and special mooring for airships. Despite the impressiveness of its statistics, the Empire State Building bombed when it first opened—the Depression was in full swing and few firms were able to afford its offices. King Kong, on the other hand, was a big box-office success and helped fill RKO’s coffers for decades. In 1981, however, the tables were turned when the now booming Empire State Building decided to celebrate the great ape’s fiftieth birthday by flying an eight-story-tall nylon balloon version of King Kong from its observation tower. Alas, the aging superstar had a rather rough time of it. No one could get him blown up properly; he kept springing leaks; and finally he had to be taken down when high winds threatened to blow away his half-inflated hulk. The whole fiasco became the subject of ridicule in the newspapers and on the radio. The real King Kong, by the way, was an eighteen-inch-tall, fur-covered jointed metal skeleton designed by a pioneer in puppet animation techniques named Willis O’Brien.

Besides King Kong, the Empire State Building has been used in countless other films. Not only does its towering presence announce that we are definitely in the greatest city on earth, its eighty-sixth-floor observation deck—usually re-created on a soundstage in Hollywood—has traditionally provided one of the screen’s most romantic rendezvous points. Think of all those Love Affairs in which it’s played a pivotal role—from the 1939 Charles Boyer–Irene Dunne original to the 1957 Cary Grant–Deborah Kerr remake (An Affair to Remember) to the 1994 Annette Bening–Warren Beatty version. The observation deck has also been immortalized in The Clock (1945), On the Town (1949), The Moon Is Blue (1953), and Sleepless in Seattle (1993), where long-distance lovers Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan finally come face-to-face high above Manhattan. For Sleepless, the building’s exterior and lobby shots were the real thing, but the deck was a set in Seattle.

On a less romantic note, the Empire State Building’s distinctive spire takes on a much different significance in the 1991 film Piñero, which documents the rise and fall of drug-addicted avant-garde Puerto Rican playwright Miguel Piñero. As the playwright, played by Benjamin Bratt of Law & Order fame, becomes increasingly undermined by his demons, the spire, at first so glamorous and seductive, comes to look ominously like a hypodermic needle.

Movie lovers wishing to visit the Empire State Building can do so any day of the week between 8 a.m. and 2 a.m. For information and prices, call 212-736-3100. In addition to the romantic observation deck, it’s possible to take an elevator to the circular, glassed-in observatory on the 102nd story. Visit www.esbnyc.com.

In architectural circles, an ultrathin high-rise is known as a sliver—and in 1993, this thirty-three-foot-wide, thirty-two-story Murray Hill apartment building provided housing for Sharon Stone as well as the name of the movie she starred in. In Sliver, the address of the building is given incorrectly—a frequent ploy of moviemakers to confuse location spotters—as 113 East 38th Street. To further complicate matters, the entrance used in the film was a much more photogenic and camera-friendly faux-glass affair created just for the film out of the sliver’s rear entrance on 36th Street.

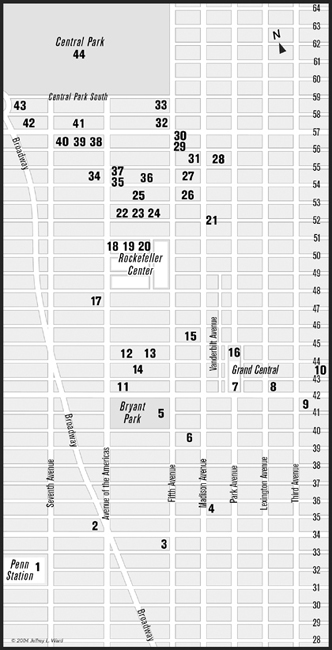

The New York Public Library

One of the city’s most impressive Beaux Arts buildings, this 1911 masterpiece is especially known for the two gigantic marble lions that guard its grand staircase. In a long-forgotten 1935 Claudette Colbert film, the library steps provide the regular popcorn-munching spot for Colbert and her buddy Fred MacMurray; the scenes involved a combination of Hollywood studio sets and real NYC footage. The same was true when the library appeared in Vincente Minnelli’s The Clock (1945), during Judy Garland and Robert Walker’s forty-eight-hour whirlwind visit to Manhattan before soldier-on-leave Walker has to report back to the base … and again in MGM’s On the Town (1949). The library can also be seen in the original Ghostbusters (1984), as the site of a ghost-busting operation that involved ridding the place of a phantom librarian who was causing trouble in the stacks. In the remake of The Thomas Crown Affair (2000), the library masqueraded as the grand foyer of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which refused to allow any part of its property to be used in a film that involved an art heist. In Spider-Man (2002), the library was the dramatic backdrop for the scene where Tobey “Spider-Man” Maguire is dropped off by his uncle (Cliff Robertson), who is later shot and killed by carjackers at the same landmark Midtown location.

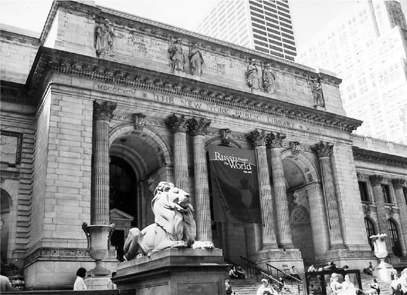

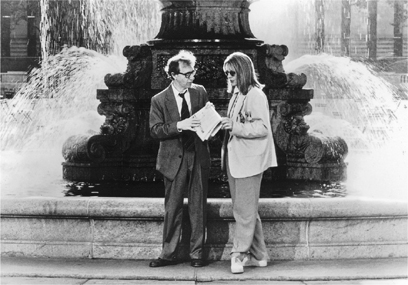

Behind the library is Bryant Park, a beautifully landscaped space with gravel walkways, folding garden chairs, and park benches. The park looks positively Parisian in Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993), when amateur sleuth Diane Keaton reports on her latest caper to her husband, Woody Allen, in front of the park’s gushing fountain. Bryant Park is also the site of one of New York City’s most glittering biannual events—Fashion Week—which sees top designers parade their latest frocks in fashion shows within huge tents; the scene is well documented in Unzipped (1995), an insider’s look at the wacky world of fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi, who lately has become a bit player in Woody Allen’s stable, having appeared in Celebrity (1998), Small Time Crooks (2000), and Hollywood Ending (2002). Bryant Park can also be seen in The Day After Tomorrow (2004) and Sex and the City (2008).

Visit www.nypl.org.

Diane Keaton and Woody Allen at the Bryant Park fountain in Manhattan Murder Mystery, 1993

For some six months in 2002, this chic boutique hotel was much in the news as the site of pop-star Britney Spears’s Nyla restaurant. Like many rising celebrities such as Jennifer Lopez, who is the principal backer of the popular Pasadena eatery Madre’s, Spears was attracted by the restaurant business to further cement her celebrity and further enrich her coffers. She was not as lucky as Lopez, however, for Nyla seems to have been cursed from the get-go, with some five hundred fans jeering Spears on the establishment’s rain-soaked opening night, when the diva arrived ninety minutes late and shot inside without even a wave to the crowd. As the months went on, Nyla was plagued with hygiene violations, morale problems among its staff, and serious financial issues. Six months after its opening, Spears severed her connection with the place, after which she was sued by a group of creditors who claimed the celebrity eatery owed them some $44,000. Nyla closed soon thereafter, but despite its failure, it nonetheless lasted somewhat longer than Spears’s January 2004 wedding to hometown pal Jason Allen Alexander, which was annulled a mere fifty-five hours after it took place. For the nuptials, held at Las Vegas’s Little White Wedding Chapel, the bride wore torn jeans and a baseball cap. She has since gotten her act—and her wardrobe—together.

NYC super station: Grand Central

Back in the glory days of Hollywood, during the 1930s and 1940s, if you were heading from New York to the West Coast, chances were Grand Central Terminal was where you would have begun your journey. And the train that you would have taken was the legendary Twentieth Century Limited, which traveled overnight to Chicago, where passengers would then board the Super Chief for the rest of their westward trek. The Twentieth Century left Grand Central every evening at around six o’clock from track 34, where a red carpet would be rolled out for departing passengers. Making their way down that carpet might have been Marlene Dietrich or Joan Crawford, with two or three redcaps in tow to handle their voluminous baggage. Both stars, according to former Grand Central redcap Oswald S. Throne, were good tippers, as was Mae West, who not only traveled with lots of luggage, but with five or six male “escorts” as well!

Alas, times and travel styles have changed. The Twentieth Century bit the dust in the mid-1960s, and Grand Central, which once was home to a number of other glamorous, long-distance trains, caters mostly to commuters these days. Still, Grand Central’s glorious 1913 Beaux Arts terminal building—with its massive marble staircase, seventy-five-foot-high windows, and twinkling-star-studded ceiling—remains one of New York City’s most dramatic public spaces. Grand Central is also a triumph of preservation. In the 1970s, it narrowly escaped “radical alterations” planned by developers who wanted to build a high-rise office building on top of it. Thanks to the commitment of concerned citizens—including the late Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who organized a grassroots campaign to ensure its landmark status—this didn’t happen, and it has since been magnificently restored.

Over the years, Grand Central (or Hollywood facsimiles thereof) has appeared in many movies. In 1934, the landmark station was the final location for Twentieth Century, the Columbia Pictures comedy about a Broadway producer (John Barrymore) and his protégée (Carole Lombard), much of which takes place aboard the train of the same name, and all of which was shot in Hollywood. Meanwhile, old-movie lovers can spot MGM’s version of Grand Central in Going Hollywood (1933) and The Thin Man Goes Home (1944). In the latter, Asta breaks loose in the terminal at rush hour and a very hungover Nick Charles (William Powell) has one hell of a time retrieving the pooch.

By the 1950s, however, going on location had become the rage. Thus, when Cary Grant needed to make a fast escape from New York City aboard the Twentieth Century, in North by Northwest (1959), director Alfred Hitchcock shot the sequence at night inside the real station. In 1965, director John Frankenheimer also used the real thing when he shot the opening sequence of the thriller Seconds at Grand Central, which tells the story of an aging businessman (John Randolph) who gets a new lease on life (and into big trouble) after plastic surgery that turns him into Rock Hudson. Other thrillers to use the dramatic terminal to great effect have been A Stranger Is Watching (1982), in which a psychopath holds a mother and child captive in a secret Grand Central cavern; Peter Yates’s The House on Carroll Street (1988), which lensed its spectacular climax on location at the station; and A Shock to the System (1990), which shows businessman-commuter Michael Caine morphing into a murderer after a younger coworker beats him out of a promotion.

Another famous Grand Central commuter was Richard Gere, who rode Metro North from Westchester to his job in Manhattan in Unfaithful (2002), whereas his wife Diane Lane traveled the same route (later in the day) to hook up with her hot young stud in Downtown Manhattan. Gere and Lane came to Grand Central under decidedly different circumstances in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Cotton Club (1984), when at the end of the film Gere gets the gangster’s girlfriend (Lane), and the two of them take off for Hollywood aboard the Twentieth Century Limited. One of the most romantic Grand Central moments ever, however, is in The Fisher King (1991), when Robin Williams and Amanda Plummer magically turn the whole place into a glittering ballroom.

Other notable films to use Grand Central include Midnight Run (1988), Loose Cannons (1990), Carlito’s Way (1993), Hackers (1995), One Fine Day (1996), Extreme Measures (1996), Conspiracy Theory (1997), Tadpole (2003), I am Legend (2007), Revolutionary Road (2008), and The Taking of Pelham 123 (2009). And finally, a trio of films with great fake Grand Central sequences: Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970), which featured a well art-directed, postapocalyptic Grand Central; the original Superman (1978), where the spectacular scenes of archvillain Lex Luthor’s fantastic subterranean Grand Central palazzo were all done on a soundstage at a London movie studio; and Sergio Leone’s saga of Jewish gangsters, Once Upon a Time in America (1984), whose Grand Central scenes were actually shot at Paris’s Gare du Nord, proving that one good gare deserves another.

Besides serving as an important movie location, Grand Central once had a CBS television studio on one of its upper stories, and the early dramatic series Man Against Crime, starring Ralph Bellamy, was broadcast live from here between 1949 and 1952. Sponsored by Camel cigarettes, the program always showed the good guys smoking, and never allowed its bad guys a single puff! Today, the old CBS studio is now a tennis club that charges over $100 an hour for a court.

Movie lovers who want to see Grand Central Terminal close-up—the building is loaded with intriguing nooks, crannies, catwalks, and a glamorous, relatively new food court—can take the walking tour sponsored by the Municipal Art Society that is given every Wednesday at 12:30 p.m. The tour meets in front of the main information kiosk on the Main Concourse—and it’s free, although donations are appreciated. All aboard!

Visit www.grandcentralterminal.com.

It must be one of New York City movie director Sidney Lumet’s favorite skyscrapers because in The Wiz, when Diana Ross and Michael Jackson ease on down the road into Lumet’s fantasy version of Manhattan as the Emerald City of Oz, no less than five Chrysler Buildings pop up on the horizon—and not one Empire State Building! Woody Allen, who once said, “There are very few modern skyscrapers that I like,” nevertheless includes the 1931 Chrysler Building on the itinerary of the architectural tour of Manhattan that Sam Waterston gives in Allen’s Hannah and Her Sisters—whereas the Empire State Building is noticeably absent. And when Dustin Hoffman points out major Manhattan landmarks to his son in Robert Benton’s Kramer vs. Kramer, the Chrysler Building tops the list.

More recently, in Two Weeks Notice (2002), Hugh Grant and Sandra Bullock circle the building in a helicopter, while Grant tells of the famous rivalry in the late 1920s between the Chrysler Building’s architect William Van Allen and his former partner H. Craig Severence to build the world’s tallest building. (Severence, who was working on the Manhattan Company Building at 40 Wall Street, lost—and both men were overshadowed a few years later when the Empire State Building made its debut.) And when Ridley Scott wants to symbolize Manhattan at its most glamorous in Someone to Watch Over Me, he dazzles us with nighttime views of this glorious 1930s high-rise. What is it about the Chrysler Building that’s so appealing? Its six-story Art Deco spire? Its huge chrome gargoyles (one of which provides the steely opening image for the 1990 film version of Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities), which were designed to look like 1931 Chrysler hood ornaments? Or simply the fact that there will never be another building quite like this one?

The Chrysler Building’s meatiest film role may well have been in a campy made-in-Manhattan monster movie called Q, about a gigantic mythological bird that comes to life and flies about zapping hard hats, window washers, penthouse sunbathers, and various other high-level New Yorkers. The creature’s nest? You guessed it … the spire of the Chrysler Building. With its inane plot and over-the-top performances by Michael Moriarty, David Carradine, Candy Clarke, and Richard Roundtree, Q is a treat not just for cult-film buffs, but for architecture lovers too, because it features lots of shots of the Chrysler Building’s sleek lobby of Moroccan marble and stainless steel and also provides rare close-up glimpses of the skyscraper’s distinctive spire from every conceivable angle.

Christopher Reeve and Margot Kidder stopped traffic back in 1977 when they emerged from the lobby of the then Daily News Building, during the filming of Superman. In this big-budget movie version of the famous comic strip, the landmark 1930 office building of a great metropolitan newspaper, the Daily News, doubled as the headquarters for the legendary Daily Planet. Especially striking, both in the Superman film and in real life, is the twelve-foot globe that revolves under a spectacular black-glass cupola in the lobby of the building, which is now simply the News Building, since the Daily News relocated to West 33rd Street in the 1990s. Movie lovers may also recall the thrilling helicopter crash that supposedly took place on the roof of the Daily Planet Building, leaving Lois Lane/Margot Kidder dangling from the side of the structure. Those sequences were a triumph of special effects—not location shooting.

Unlike Hollywood, where most of the film and TV facilities are concentrated in large studio buildings and complexes, New York constantly surprises with its many small studios dotted across the city. A case in point is this CBS-run soundstage, longtime home to the soap opera The Guiding Light, which went off the air in 2009. Among the New York actors who performed on this venerable soap early in their careers are Kevin Bacon, Sarah Michelle Gellar, Allison Janney, Mira Sorvino, and JoBeth Williams.

Visit www.screengemsstudios.com.

The daring cable network that frequently leaves the big television networks in the dust—with sophisticated, edgy, and frequently sexually explicit series like Sex and the City, Six Feet Under, and The Sopranos—has its New York City base here. Besides TV series, HBO is known for its award-winning TV movies, miniseries, and docudramas. Among them are Band of Brothers, And the Band Played On, Barbarians at the Gate, Gotti, Truman, Gia, Citizen Cohn, Winchell, Angels in America, Elephant, Game Change, Grey Gardens, The Laramie Project, Too Big to Fail, and When the Levers Broke.

Visit www.hbo.com.

The Algonquin Hotel’s legendary Rose Room

A hotel that is a literary landmark, the Algonquin will always be linked to an irreverent group of Manhattan intellectuals, known as the Round Table, who hung out in its Oak Room and later in its Rose Room in the 1920s and 1930s. The crew included critics Alexander Woollcott and Robert Benchley, playwright George S. Kaufman, essayist and short-story writer Dorothy Parker, humorist Ring Lardner, actress Tallulah Bankhead, and New Yorker editor Harold Ross (who is said to have put together the magazine at the hotel rather than in its offices across the street). Although most of the Round Table held the movies, and especially Hollywood, in disdain, many of them eventually developed pretty strong ties with the film industry when the studios offered one of the best sources of employment for writers during the Depression. Of the elite Algonquin group, Dorothy Parker wound up spending the most time in Hollywood, where she worked on the screenplays for such classic films as David O. Selznick’s 1937 A Star Is Born (for which she shared an Oscar with her coauthor husband Alan Campbell) and Hitchcock’s 1944 espionage thriller Saboteur.

It was also in 1944 that Hollywood immortalized the Algonquin’s Rose Room with Otto Preminger’s quirky murder mystery Laura, featuring a scene set in the historic dining room where the Round Table held forth. Laura‘s Rose Room, of course, was a facsimile created on a soundstage at Twentieth Century–Fox, but when director Alan Rudolph immortalized the Round Table in his 1994 Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle, although the film was mainly shot in Montreal for budgetary reasons, the real Algonquin was one of the few New York City locations used for the picture. Jennifer Jason Leigh played Parker, with Peter Gallagher as her handsome husband Alan Campbell; other Round Table members were Campbell Scott as Robert Benchley, Matthew Broderick as Charles MacArthur, and Sam Robards as Harold Ross.

Another film that featured the Algonquin playing itself was 9½ Weeks, where it was one of the spots where Mickey Rourke and Kim Basinger engaged in kinky sex in the 1986 Adrian Lyne feature. Five years earlier the hotel had been the scene of an amusing literary-sexual encounter in George Cukor’s Rich and Famous. In the film, neurotic writer Jacqueline Bisset is giving a tour of the Algonquin, along with a history of the Round Table, to a much younger man she has just picked up and is about to escort up to her room.

This was all a far cry from a century ago, when it was in the Algonquin’s lobby—a cozy clutter of Victorian armchairs, sofas, and coffee tables—that Douglas Fairbanks first wooed Mary Pickford back in the 1910s. Fairbanks, who kept a suite at the Algonquin from 1907 to 1915, was the first of many film stars who thought of the Algonquin as home. Other legendary habitués were Audrey Hepburn, Billy Wilder, Sir Laurence Olivier, Yves Montand, and Melina Mercouri—all of whom loved the Algonquin for its proximity to the theater district, its lobby so perfect for cocktails and/or a proper British tea, its chandelier-hung dining room that serves old-fashioned hotel food like chicken pot pie and calf’s liver with bacon. Happily, despite the current rage for minimalist hotels, here at the Algonquin, very little has changed, although the historic Rose Room has been redone and rechristened The Round Table.

Visit www.algonquinhotel.com.

Not nearly as historic or fashionable as its next-door neighbor, the Algonquin, the Iroquois can nonetheless claim a young actor named James Dean as a former resident. This was during the dawn of his New York career back in the early 1950s, when the only acting job he could manage to find was as a guinea pig testing out the wacky stunts for the producers of the popular TV game show Beat the Clock. At the Iroquois, Dean occupied room number 802, which he shared with fellow actor William Bast. In those days, both guys, if they were meeting someone they deemed important, would arrange to see them next door in the lobby of the Algonquin. Today, the same ploy is no longer necessary, because the Iroquois has been considerably spiffed up since its James Dean days.

Visit www.iroquoisny.com.

One of Manhattan’s hippest hostelries, the Royalton debuted in 1988 as the brainchild of ex–Studio 54 ex-cons Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell. With the help of über-designer Philippe Starck, they took over an aging hotel on West 44th Street and made it the last word in minimal decor and maximum profile. Immediately the stars of New York publishing flocked to its restaurant—Vanity Fair‘s Tina Brown, Vogue‘s Anna Wintour, and the late fashion doyenne of the New York Times Carrie Donovan. The supermodels all hung out here, too—Linda, Christy, Cindy—in the days when they reigned on the covers of all the major fashion magazines before being dethroned by beautiful young movie stars. The hotel was also used for premiere parties for such films as This Boy’s Life (1993), which brought Leonardo DiCaprio to the hotel for the first of many visits and interviews over the years. Today, the Royalton is no longer Schrager’s, but it is still a happening place to stay and play, even if the initial buzz is decidedly more muffled. Indeed, when the 2001 Tom Cruise film Vanilla Sky, set in the publishing world, needed an appropriately insider location for a hotel scene, they went with the Royalton.

Visit www.royaltonhotel.com.

Since 2002, the twelfth floor of this Madison Avenue high-rise has been headquarters for the New York City offices of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG), which merged with the performers’ union American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (AFTRA) in 2012. Pre-merger, out of a total of 125,000 members nationwide, some 32,800 actors belonged to SAG in the New York metropolitan area. For a day’s work in a theatrical film, the 2012 SAG minimum base rate was $842 for a day (featured) player and $145 for a background actor (extra).

Visit www.sagaftra.org.

One of New York’s first precast concrete skyscrapers, this Park Avenue landmark sparked a great deal of controversy when it came on the scene in 1963, since it blocked views up and down Manhattan’s most elite street. The work of legendary Bauhaus architect Walter Gropius, who collaborated with various other architects on the project, it was named the Pan Am Building for the once grand, now defunct airline that was headquartered here for almost twenty-five years. The structure’s stunning marble lobby, with its dramatic public art works and floating escalator banks, was featured in the 1968 film No Way to Treat a Lady, where serial-killer Rod Steiger uses the marble phone banks in the lobby to phone police headquarters, outraged that a strangulation victim has been attributed to him when it was the work of a copycat. Other 1960 films that took advantage of the then new building’s cachet include On a Clear Day You Can See Forever (1970), where Yves Montand sings “Come Back to Me” to a distant Barbra Streisand from the rooftop of the sixty-five-story building in the Vincente Minnelli–directed musical; and Coogan’s Bluff (1968), which has western sheriff Clint Eastwood arriving in NYC in a helicopter that lands atop the Pan Am Building’s famous heliport, which enabled travelers to hop from JFK to Midtown Manhattan in a matter of minutes. In 1977, however, those days came to an end when a helicopter flipped over and its rotors broke off, killing four people on the roof—including porn film director Michael Findlay, known for classics like Wet and Wild (1976) and The Curse of Her Flesh (1968)—and one person on the ground.

More recently, the former Pan Am Building—complete with its old sign—turns up in Catch Me If You Can. In the film, which is set in the 1960s, con man Leonardo DiCaprio, in his efforts to impersonate an airline pilot, phones Pan Am from a booth outside the building to find out who supplies their uniforms.

In 1985, Australian publishing mogul Rupert Murdoch went shopping for a movie company to add to his growing portfolio of U.S. media acquisitions. He bought the venerable studio Twentieth Century–Fox and for a while in the early 1990s even ran it himself, when then CEO Barry Diller resigned. Today, Murdoch’s News Corp. empire includes not only the Fox movie division but Fox News, HarperCollins publishers, the New York Post, the London Times, and the Sky cable network—and that’s just the beginning. Murdoch’s prime New York base of operations is here on Sixth Avenue, where the hyper-fit septuagenarian recently built a large gym to encourage his staff to be as healthy as he is. Vanity Fair put Murdoch at the very top of its 2003 list of the fifty most important media people in America; in 2011, plagued by a phone-hacking scandal, he fell to the number-four spot.

Visit www.newscorp.com.

Postcard view of Radio City Music Hall stage

It advertised 6,200 seats, but the total has always been closer to 5,960. Still, when Radio City Music Hall opened in 1932 as part of New York’s futuristic Rockefeller Center complex, it was the largest indoor theater in the world. And today it still is. Everything about Radio City Music Hall is outsized—from its sixty-foot-high foyer to its two-ton chandeliers (the largest in the world) to its Wurlitzer organ (the mightiest on earth, with fifty-six separate sets of pipes).

While many people assume that this great Art Deco theater started out as a movie palace, Radio City Music Hall was actually planned for spectacular stage shows, whereas the now defunct Center Theater on the next block was to have been Rockefeller Center’s main venue for films. When the Music Hall’s six-hour opening-night program bombed, however, the enormous theater quickly turned to the formula that would spell its success for the next three decades: a thirty-minute stage show combined with a first-run family movie. More than just a commercial success, Radio City Music Hall—with its high-kicking Rockettes, spectacular Christmas and Easter pageants, and top-notch movies—became an entertainment landmark of New York City, a must on every visitor’s list of things to see and do.

Not only has it played a role as an important site for the New York premieres of more than six hundred films like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), An American in Paris (1951), and Singin’ in the Rain (1952), the hall has also wound up being featured in a number of films including The Godfather (1972), Annie (1982), Radio Days (1987), and Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942), in which Robert Cummings runs across a Hollywood mock-up of the Radio City stage while a film is being shown. Since a gunfight is taking place on screen, the audience at first doesn’t realize that a real gun is being fired at Cummings in the theater.

Radio City’s glory days ended in the 1960s. For one thing, the studios had started mass-releasing films by then, making it next to impossible for Radio City still to boast first-runs. Also, America’s tastes had changed. Family films were out of fashion in the 1960s and 1970s, and the Rockettes kicking up their heels were considered high camp, not mass entertainment. By 1978, Radio City was losing millions of dollars a year, and the Rockefeller Group, its parent company, decided to close it down. A white elephant, the grand Art Deco entertainment palace was earmarked for demolition. Happily, a citizens group managed to get the interior of the Music Hall declared a historic landmark and management set about finding new uses for the mega-auditorium.

And so, these days, Radio City Music Hall hosts everyone and everything from rock and pop stars and groups (Madonna, Sting, the Rolling Stones, Grateful Dead, Bette Midler, Liza Minnelli, Tina Turner, Janet Jackson, Celine Dion, Whitney Houston, Stevie Wonder) to trade shows and awards shows (the Tony Awards, MTV Music Awards, ESPY Awards) to TV specials and its own classic Christmas and Easter extravaganzas. And, while movies no longer play a major role in Radio City’s life, special screenings still go on here from time to time, such as the New York premieres of Disney’s The Lion King (1994) and the 1983 New York first showing of the restored version of the Judy Garland/James Mason A Star Is Born, which featured the “lost” twenty-four minutes that had been cut from the film by Jack Warner back in 1954. Radio City is also where Francis Ford Coppola first unveiled his reconstructed version of Abel Gance’s 1927 silent-screen epic Napoleon before New York audiences. The music for the revived film was composed by Coppola’s father, Carmine.

Movie lovers can experience the splendor of the Radio City Music Hall either by attending a performance or by taking an hour-long backstage tour of the place. Tours are given daily from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m.; they depart from the Main Lobby. Call 212-247-4777 and ask for the Tour Desk, or visit www.radiocity.com.

It makes for one hell of an establishing shot: a long pan down the seventy stories of the RCA Building to the gigantic gilded statue of Prometheus backed by a row of fluttering flags and spurting jets of water. Hold on the statue, then pull back and angle down to reveal a huge outdoor café—or, if it’s winter, an ice skating rink. Pull back farther to include a long courtyard studded with a series of lavishly planted mini-gardens. Or do the whole sequence in reverse. Rockefeller Center, which the American Institute of Architects’ AIA Guide to New York City calls “an island of architectural excellence … the greatest urban complex of the twentieth century,” is so beautifully laid out, so well proportioned, so perfect that it’s hard to make it look anything less than extraordinary, no matter how you shoot it. Used in the movies, a shot of Rockefeller Center—as in Nothing Sacred (1937), How to Marry a Millionaire (1953), or Manhattan (1979)—establishes New York at its best: a perfectly balanced combination of power, glamor, and humanity.

Add the skating rink—especially when backed by the most renowned Christmas tree in America—and we see Midtown Manhattan at its most romantic in films such as Desk Set (1957), Sunday in New York (1963), 40 Carats (1973), Home Alone 2 (1992), and Autumn in New York (2000). Or focus on the forecourt of the center’s Atlas Building at 630 Fifth Avenue—with its dramatic statue of the Greek god Atlas holding the world on his shoulders—and you enhance the already powerful image of this serious office building, which has been used as the talent agency that could change violinist John Garfield’s life in the 1947 Joan Crawford melodrama Humoresque; the magical spot where has-been journalist Bruce Willis is given the tip for a sensational story that will jump-start his sagging career in the 1990 film version of Tom Wolfe’s blockbuster novel The Bonfire of the Vanities; and the newspaper where Gregory Peck has gone undercover to do his big story on anti-Semitism in Elia Kazan’s Gentleman’s Agreement (1947). Especially memorable in this film is the scene where Peck, echoing his own emotional state, explains the burden Atlas is shouldering to his young son. On the other hand, in Hercules in New York (1970), Arnold Schwarzenegger (under the stage name of Arnold Strong), in the title role, not only knows who Atlas is, but says the statue is not a good representation of his fellow muscleman.

On the Town at Rockefeller Center: Frank Sinatra, Jules Munshin, Gene Kelly, 1949

Besides the many films that use Rockefeller Center as background, two recent features have focused on a unique aspect of its history. When Rockefeller Center was being built, the famous Mexican artist Diego Rivera was commissioned to do the murals in the then RCA (now GE) Building at 30 Rockefeller Plaza. But when it was discovered the left-wing Rivera had included and refused to delete a likeness of Lenin, hypercapitalist John D. Rockefeller fired Rivera and brought in artist José Maria Sert to do a whole new set of paintings. The incident is referenced both in The Cradle Will Rock (1999), Tim Robbins’s homage to left-wing New York of the 1930s, and in Frida (2002), a biopic produced by and starring Salma Hayek as Rivera’s artist wife, Frida Kahlo. In the film Edward Norton plays Rockefeller and Alfred Molina is Rivera.

Conceived and founded by John D. Rockefeller, the twelve high-, middle-, and low-rise buildings that comprised the original Rockefeller Center were built between 1930 and 1940. The centerpiece of the complex is the seventy-story GE Building (formerly the RCA Building). When Rockefeller first envisioned his urban center in the 1920s, his plan was to provide a new home for the Metropolitan Opera House (it was on Broadway at 38th Street at the time) to be surrounded by office, retail, entertainment, and dining facilities. When the Depression hit in 1929, the Met decided that it couldn’t afford to move, so Rockefeller and his advisers decided to build an office tower instead of an opera house. At the same time, the Radio Corporation of America and its subsidiary, the National Broadcasting Company, were among the few companies in the country that were prospering despite the Depression. Looking for a corporate headquarters to suit their growing needs and power, RCA/NBC found a classy home at Rockefeller Center and became the principal tenant of the handsome skyscraper at 30 Rockefeller Plaza, which opened in 1933 bearing the RCA name (which was changed to GE in the 1980s, reflecting RCA/NBC’s new owner General Electric).

For the radio and television lover, 30 Rockefeller Plaza—which still houses NBC’s principal New York radio and TV studios—is today a household word owing to the popularity of the TV series that bears its nickname: 30 Rock. Aside from the series, this address is one of the most historic sites in the country connected with radio and television. Television literally came of age here beginning in 1935, when NBC started broadcasting two programs a week from studio 3H. These first telecasts consisted of plays, comedians, scenes from opera, cooking demonstrations (limited to salads because the intense heat from the then necessary ultra-high-powered TV lights made stovetop cooking unthinkable), and even live transmissions from the streets of New York thanks to a mobile unit that went into operation in 1937. Despite these experiments, it wasn’t until after World War II that TV really got off the ground. Then, too, NBC was at the forefront of the medium with such programs as Kraft Television Theatre (1947), Howdy Doody (1947), the John Cameron Swayze–anchored Camel News Caravan (1947), Meet the Press (1947), and Milton Berle’s Texaco Star Theatre (1948)—most of which were televised from Radio City.

In 1952, NBC took a bold step in early-morning programming by introducing a two-hour show that mixed news, interviews, and entertainment features. The host of NBC’s new Today show was a laid-back gentleman named Dave Garroway and one of his sidekicks was a chimpanzee named J. Fred Muggs. Instead of using a studio in 30 Rockefeller Plaza, however, the Today show was done live from a spacious Rockefeller Center showroom with street-to-ceiling picture windows on the south side of West 49th Street just west of Rockefeller Plaza. Passersby pressed their noses up against the glass to watch the live TV production going on inside, and at various times each morning the camera was turned on the gawkers. Soon Today not only became a hit television show, it became a major New York City tourist attraction. In the 1960s, Today revamped its studios, and its old 49th Street base was turned into a bank. In 1994, however, Today not only returned to a street-level studio at 10 Rockefeller Plaza, it started shooting out on the plaza itself—and sign-carrying spectators line up well before dawn in hopes of prime places and possible close-ups.

For TV lovers, an early-morning visit to the Today show can be followed by the fifty-five-minute NBC Studio Tour. Among the attractions of this behind-the-scenes look at Radio City are studio 8H, the Saturday Night Live auditorium as well as the site of such classic early TV shows as Your Hit Parade, What’s My Line, and the Kraft Television Theatre. The tour also takes television lovers to Studio 1A, home to the Today show.

The NBC Studio Tour is currently given daily at fifteen-minute intervals. Tours leave from the NBC Tour Desk on the main floor of 30 Rockefeller Plaza; admission is currently $17.50 for adults, $15 for seniors and children from six to sixteen. No one under six allowed. Call 212-664-3700. To buy tickets online, go to http://nbctelevision-studio-tour.visit-new-york-city.com.

With its glorious views, its revolving dance floor, and its stunning Art Deco interiors, Rockefeller Center’s sixty-fifth-story Rainbow Room was the last word in New York City nightlife when it opened in 1934. Over the years, as supper clubs went in and out of fashion, the magnificent venue has had various incarnations, one of the most recent being the classy cabaret nightclub Rainbow and Stars, which featured such legends as Liza Minnelli and the late Rosemary Clooney. Alas, the Rainbow Room has been closed since 2009, although rumors of a redo and reopening continue to swirl—especially since its interior was declared a New York City landmark in October of 2012. Meanwhile, movie lovers can also catch the Rainbow Room in all its glory in The Prince of Tides (1991), where Barbra Streisand dances with Nick Nolte; Six Degrees of Separation (1993), where Will Smith dances with Eric Thall (and is asked to leave); and Sleepless in Seattle (1993), where Meg Ryan breaks her engagement to Bill Pullman.

In the beginning there was NBC … and only NBC. Then, in 1927, a new radio network called the Columbia Phonograph Broadcasting System came along to challenge the National Broadcasting Corporation’s monopoly of the airwaves. The new network had a rough go of it initially. When its owners, the Columbia Phonograph Record Company, backed out, a young cigar magnate named William S. Paley stepped in, shortened the network’s name to the Columbia Broadcasting System, and perked up its credit rating by getting powerful Paramount Pictures to come in on the deal. Thus it was with great pride and much fanfare that, in the autumn of 1929, Mr. Paley cut the ribbon for CBS’s headquarters in the brand-new Columbia Broadcasting Building at the corner of Madison Avenue and 52nd Street.

CBS occupied the top five floors of the impressive new twenty-four-story structure and had fifteen studios on the premises; these ranged from tiny chambers to an auditorium large enough to hold 250 performers. Some of the studios were equipped with glassed-off, soundproof balconies to accommodate spectators for early radio shows, and one studio was set up for what everyone knew was coming sooner or later: television. Indeed, many important early experiments in television took place in the CBS Building in the 1930s. In those days performers had to wear garish makeup, and the primitive camera, with its high-powered spotlight, practically blinded the actors after just a couple of seconds in front of it.

But it was radio that was responsible for CBS’s great success in the 1930s and 1940s. As the country’s number-two network, CBS devoted most of its energies to its radio programming in order to catch up with top-ranked NBC. Meanwhile, NBC was so convinced that television was just around the corner that it let its radio division slide as it moved full speed ahead on the development of TV. Thus, by the end of the 1930s, CBS—with a strong news division that included pros like Edward R. Murrow and Eric Sevareid, and equally impressive dramatic programming that featured the talents of Orson Welles and Archibald MacLeish—was a force to be reckoned with. When World War II erupted and further delayed the coming of television, CBS’s position in the industry was made even stronger.

CBS and Mr. Paley stayed at 485 Madison Avenue for thirty-six years. When the network moved into its current headquarters at 52nd Street and the Avenue of the Americas in 1965, it was Mr. Paley who, in the tradition of ships’ captains, was the last person to leave 485 Madison Avenue. Paley died in 1990.

Known as Black Rock, this thirty-eight-story Eero Saarinen–designed skyscraper of Canadian black granite has been the corporate headquarters of CBS since 1965. No longer an independent company, CBS is currently part of the massive media conglomerate Viacom, which also counts Paramount Pictures, MTV, Showtime, and VH1 among its family members. Viacom paid a cool $40.6 billion to acquire CBS in 1995.

In 1977, Black Rock was featured in the film Exorcist II: The Heretic. In this lame follow-up to the famous supernatural thriller, the formerly possessed Regan MacNeil (Linda Blair) is now living in New York in her actress mother’s posh penthouse, which supposedly is in Black Rock. Director John Boorman used this high-up location for numerous vertigo-inducing terrace scenes.

The brainchild of CBS founding father, the late William S. Paley, the former Museum of Television and Radio—which now bears his name—was founded in 1976. The first institution to be dedicated exclusively to the preservation, cataloguing, and showcasing of radio and television art, the museum has accumulated over 100,000 television and radio programs in its archives. Open to media scholars and fans alike, the museum provides custom-built private viewing consoles where individuals can screen the titles they have requested from the museum’s computerized database.

Besides providing an opportunity for individuals to explore radio/TV history firsthand, the museum has a program of TV and video screenings, which it presents in two theaters and two screening rooms. These can be anything from an examination of James Dean’s career in early television to Sex and the City marathons to “Sound and Vision: David Bowie on Television.” A sign of the museum’s success is the fact that it opened a Beverly Hills branch in 1996.

The Paley Center for Media is open Wednesdays to Sundays, from noon to 6 p.m and noon to 8 p.m. on Thursdays. Suggested contributions: $10.00 for adults; $8.00 for students/senior citizens; $5.00 for children under thirteen. Call 212-621-6608 or visit www.paleycenter.org.

When Karen Richards, wife of playwright Lloyd Richards, has a lunch date with Margo Channing, Broadway’s reigning leading lady, in All About Eve, the setting is naturally the 21 Club. And when Karen arrives at 21, whom should she bump into but Addison DeWitt, the all-powerful newspaper columnist, who just happens to have the up-and-coming Broadway actress Eve Harrington in tow!

In the days of All About Eve (the early 1950s), 21 was one of the places in New York for the rich and the famous to break bread together. It still is. Here, on any given day, you’re likely to find a cast of characters that might include Donald Trump, Hugh Jackman, Julianne Moore, Chris O’Donnell, Brooke Shields and Chris Henchy, and Hillary Swank and Chad Lowe. You may not find critic Rex Reed at 21, however, since he was once barred from the dining room for not having a tie. “But this is Bill Blass,” Reed is reported to have protested, referring to his dapper sports coat. Still, he flunked the stringent 21 dress test and was refused entry.

In a city that is constantly changing, 21 adheres to its traditions—from dress codes to not tolerating customers who insult waiters to ejecting patrons who’ve had too much to drink (allowing them to return the next day if they’re sober) to not “selling” choice tables. Indeed, for many, 21 has served as a club, a place where they could go anytime and always count on finding a warm welcome and no surprises. It was no doubt this strong sense of continuity that attracted Humphrey Bogart to 21, and today his table—number 30 in the downstairs bar—is still known as Bogie’s Corner, indicated by a sign hanging nearby. Upstairs, in the main dining room, Joan Crawford always had the table just to the left of the entrance.

It may come as a surprise to some that this bastion of Manhattan luxury started out as an expensive speakeasy. Founded in 1930 by Jack Kriendler and Charlie Berns, 21 was then equipped with an elaborate security/screening system, secret cellars that concealed some five thousand cases of liquor, and a James Bond–like bar that could automatically dispose of all the booze on the premises in the event of an unexpected visit from the feds. In those days, the block of 52nd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues was one of the city’s liveliest spots, noted for its speakeasys, restaurants, and nightclubs. Today, the same block is wall-to-wall office towers. The sole survivor from the street’s glory days is the cluster of three brownstone townhouses that together form 21. With its wrought-iron grill, old-fashioned lanterns, two American flags, and row of cast-iron jockey statues out front, 21—despite occasional changes in ownership—remains a monument to a glamorous New York that once was and that, inside 21 at least, lives on.

The restaurant also lives on in other films besides All About Eve. In Written on the Wind (1956), directed by “women’s picture” maven Douglas Sirk, 21 was the spot where Rock Hudson and Robert Stack began their rivalry for Lauren Bacall, and in Sweet Smell of Success (1957), when press agent Tony Curtis and jaded newspaper columnist Burt Lancaster exit 21, they see a drunk being thrown out of a nearby bar—to which Lancaster responds with: “I love this dirty town.” A popular power-lunch spot in real life and reel life, 21 saw Michael Douglas as that ultimate 1980s corporate animal Gordon Gecko lunching with his protégé Charlie Sheen in Wall Street (1987), whereas Whoopi Goldberg does a meeting here with Eli Wallach, Lainie Kazan, and Timothy Daly in The Associate (1996). The restaurant also provides festive dining in Metropolitan (1990), Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993), One Fine Day (1996), and Morning Glory (2010).

Call 212-582-7200; visit www.21club.com.

In addition to its trove of van Goghs, Picassos, Monets, and Mondrians, the Museum of Modern Art—after its recent two-year, $850-million redo—counts among its treasures important works by De Mille, Chaplin, Griffith, Porter, Stiller, and Méliès. In fact, MoMA has some twenty thousand films in its archives spanning the medium’s history from late-nineteenth-century silents to twenty-first-century video art.

Believing that film was “the only great art peculiar to the twentieth century,” former MoMA director Alfred H. Barr Jr. established the Department of Film at the Museum of Modern Art in 1935, and immediately sent curator Iris Barry on a special mission to Hollywood to drum up support for his innovative undertaking. There, at a party given by Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks at Pickfair, their lavish Beverly Hills estate, Miss Barry met industry heavyweights like Samuel Goldwyn, Harold Lloyd, Harry Warner, Harry Cohn, Ernst Lubitsch, Mervyn LeRoy, Walt Disney, Jesse Lasky, and Mack Sennett. Returning to New York with what the Los Angeles Times reported to be “more than a million feet” of film, Miss Barry had the beginnings of MoMA’s collection. But one old-timer who was not as forthcoming as many of his Hollywood colleagues was D. W. Griffith, who refused to donate his own films to the museum, reportedly saying that nothing could convince him that films had anything to do with art. Ultimately MoMA enlisted the aid of Griffith’s friend and former star actress, Lillian Gish, who eventually persuaded him to hand over to history his collection of films, music, still photographs, and papers. It seems, however, that it was the lure of the tax write-off that was really responsible for Griffith’s change of heart.

For the movie lover, the best thing about MoMA’s film collection is that it is constantly on view. The museum has two theaters—one with 460 seats, the other with 217—which together are used to present some two dozen screenings a week. The Department of Film and Media–MoMA also cosponsors, with the Film Society of Lincoln Center, the New Directors/New Films festival, which is held every year in March/April. In addition to showing films, the Department of Film and Media–MoMA maintains a library of film books, screenplays, reviews, publicity material, and four million stills that is an important research center for students, authors, and historians.

By far the most important activity of the Department of Film and Media–MoMA is its work in film preservation. A frightening fact is that, of all the feature films made before 1952, half have disappeared entirely; of those produced before 1930, only a quarter survive, since the nitrate stock on which they were shot eventually self-destructs. Newer motion pictures, especially those shot on color-negative film during from the 1950s to the 1970s, are endangered too because the dyes in their negatives are unstable. As a result, many important classics from these decades—Rebel Without a Cause (1955), Tom Jones (1963)—have faded or are fading fast. Despite the fact that tremendous amounts of money are needed to transfer older movies onto newer, more stable film stock, MoMA perseveres in its noble goal of preserving the modern era’s unique art form.

Screenings by the Department of Film and Media–MoMA are presented free to MoMA members and are open to the general public for a modest admission charge. For information, call 212–708-9480, or visit www.moma.org.

Built in 1967 by CBS founder William S. Paley in honor of his father, Samuel Paley Plaza is a pleasant little park with tables, chairs, trees, and a waterfall. A popular place in warm weather for Manhattanites and tourists to have light lunches or snacks, the park stands on the site of what was once one of New York City’s most fashionable watering holes: Sherman Billingsley’s famous Stork Club. Always crammed with celebrities, the Stork Club was the favorite hangout of columnist Walter Winchell, who kept the rest of the country informed of its glamorous goings-on.

Stork Club stars: Henry Fonda, Joan Crawford, Ruth Warrick, Peggy Ann Garner, Walter Winchell, and Dana Andrews in Daisy Kenyon, 1947

The most exclusive place to be seated at the Stork Club was in the small Cub Room, which owner Billingsley reserved for stars (many of whose portraits graced the walls) and socialites. The rest of the world had to make do with a table in the main dining room, which had a large dance floor and nonstop music. In both rooms, and at the long bar, Billingsley ran a tight ship. His strictly enforced house rules included refusing admittance to unescorted women at night, although they could turn up for lunch or at cocktail hour; also, any customer who started a fight was permanently barred from the premises.

So great was the fame of the Stork Club that Billingsley was contracted by the Encyclopaedia Britannica to write its first entry on nightclubs. In addition, the club was immortalized in the movies, notably in Hitchcock’s made–in–New York The Wrong Man (1957), with star Henry Fonda in the role of a Stork Club bass player, and in Otto Preminger’s Daisy Kenyon (1947), where columnists Walter Winchell and Leonard Lyons play themselves in a dramatic Stork Club sequence toward the end of the film. The club closed in 1965, made a brief comeback on Central Park South in the 1970s, and now lives on on video and DVD.

Built by Col. John Jacob Astor, this was the tallest (eighteen stories) and most luxurious hotel New York had ever seen when it went up in 1904. Public rooms were decorated with the finest European furnishings; china was by Royal Worcester, Royal Minton, and Sèvres. There was marble everywhere—in stairways, corridors, even in the basement engine and boiler rooms! Many guest rooms came with their own Steinway pianos, and all were equipped with such then unheard-of innovations as automatic vacuum-cleaning systems and individual thermostats to control the temperature and humidity of the rooms.

With all its amenities, the St. Regis attracted quite a few glamorous guests over the years—from Humphrey Bogart (it was Bogie’s favorite Manhattan hotel) to Marilyn Monroe, who stayed at 2 East 55th Street when she came to town in 1954 to do location shooting for The Seven Year Itch. Her marriage to Joe DiMaggio was in serious trouble at the time, but matters got a lot worse the evening she shot the infamous scene on Lexington Avenue in which her skirt gets blown up by the air from a passing subway train. Supposedly, the fight that followed between Monroe and DiMaggio in their St. Regis suite was so intense that it woke up the whole floor.

Three decades later, the characters played by Michael Caine and Barbara Hershey in Hannah and Her Sisters get along much better in their St. Regis room, which they use as a trysting place in the 1986 Woody Allen film. Hotel sources point out that only the hotel’s handsome Beaux Arts façade was used in the film, and that the interior of the suite shown on screen was decidedly less grand than a real St. Regis room. Woody made up for the slight when he returned to the hotel the next year to shoot Radio Days, which featured the St. Regis’s King Cole dining room as the elegant 1940s nightclub where a blond Mia Farrow works as a cigarette girl. The same bar saw Goldie Hawn, playing an actress in The First Wives Club (1996), try to drown her sorrows in alcohol after being told she was too old for a role.

More recently, both Woody Allen and Michael Caine returned to the St. Regis: Allen for his 2003 film Anything Else and Caine for Miss Congeniality (2000), where he lunched at the hotel’s ultraposh Lespinasse restaurant with detective Sandra Bullock and discussed how she would infiltrate a beauty contest. The only place movie lovers will find Lespinasse these days is in the film, however, since it was one of the first big-ticket restaurants to fold after 9/11. Movie lovers can also spot the St. Regis in Taxi Driver (1976), where the landmark provides one of the few beautiful images in Martin Scorsese’s otherwise relentlessly depressing view of Manhattan.

Visit www.stregis.com.

This English Renaissance townhouse in Midtown Manhattan has, since 1956, served as headquarters for one of the most famous private clubs in America—the Friars. Among its officers have been: Frank Sinatra, head abbot; Milton Berle, abbot emeritus; Sammy Davis Jr., bard; Tom Jones, knight; Paul Anka, herald; Alan King, monitor; Howard Cosell, historian; Henny Youngman, squire. Founded in 1904 by a group of New York theatrical press agents in order to separate the legitimate members of their profession from the numerous frauds who misrepresented themselves to producers in order to gain free admittance to the theater, the Friars eventually evolved simply into a club for members of the theatrical profession. If movie lovers can wangle an invitation to the Friars’ 55th Street “monastery,” they will find a dining room and Round the World Bar (named for former abbot Mike Todd’s 1956 film, Around the World in Eighty Days) on the first floor, the Milton Berle Room and Joe E. Lewis Bar on the second, the Ed Sullivan Reading Room and Frank Sinatra TV-Viewing Room on the third, a billiards room and barber shop on the fourth, a health club on the fifth, and a solarium and golf practice net on the roof.

World-famous for their celebrity roasts, the Friars over the years have so honored Jack Benny, Bob Hope, George Jessel, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Ed Sullivan, Perry Como, Dinah Shore, Garry Moore, Johnny Carson, Burt Reynolds, Barbra Streisand, Tom Jones, Carol Burnett, Cary Grant, Elizabeth Taylor, George Burns, George Raft, Lucille Ball, Sid Caesar, Whoopi Goldberg, Billy Crystal, Bruce Willis, Kelsey Grammer, Danny Aiello, Drew Carey, and Rob Reiner. For many years, these roasts were stag affairs, and the jokes and language went well beyond being X-rated. In 1983, comedian Phyllis Diller made show-business history when, disguised as a man, she crashed a Friars roast for Sid Caesar. Phyllis, who even used the men’s room at the Sheraton Centre Hotel on Seventh Avenue, where the event was held, managed to get through the whole affair without being discovered. Said Phyllis of the proceedings: “It was the funniest, dirtiest thing I ever heard in my life. Of course, I had already heard this language before, because I once ran into a truck.” In 1988, Liza Minnelli made more history when she was the first woman invited to become a full-fledged Friar.

Visit www.friarsclub.org.

One of big-ego real-estate mogul Donald Trump’s many Manhattan monuments, this mirror-glass tower has offices and a six-story atrium with waterfall on its lower floors, and ultraposh apartments higher up. Of all its apartments, none is more lavish than that of the Donald himself, which takes over the top four floors of the building. In the movies, the same flat was home to Trump-like property developer Alexander Cullen, played by Craig T. Nelson, in The Devil’s Advocate (1997), and both Trump’s apartment and Trump himself appeared in the 1987 miniseries I’ll Take Manhattan, based on the Judith Krantz pop novel. The Trump Tower rooftop was also one of Tobey Maguire’s Spider-Man high-rise haunts in the 2002 film. But it and its owner have really come into their own with the 2003 debut of the reality TV show The Apprentice, which features lots of the carrot-haired exec on location at his glitzy Fifth Avenue lair.

In addition to the Donald, others famous Trump Tower denizens have included Sophia Loren, Pia Zadora, Johnny Carson, Steven Spielberg, Paul Anka, Martina Navratilova, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Susan Saint James, and the original King Kong star, the late Fay Wray.

“Don’t you just love it? Nothing bad can ever happen to you in a place like this.” Thus spoke Audrey Hepburn as Holly Golightly, the ultimate Manhattan free spirit, in the 1961 Paramount version of Truman Capote’s best-selling novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s. For the film, which was directed by Blake Edwards, at the time known mainly as the creator of the Peter Gunn and Mr. Lucky TV series, a number of New York City locations were used, including exteriors and interiors of the legendary Tiffany & Co. jewelers. Tracing its roots back to 1837 (and its current Fifth Avenue location to 1940), Tiffany’s made certain that the Sunday shooting of the film went smoothly by stationing forty of its own security guards and salespeople around the store to keep an eye on the millions and millions of dollars’ worth of sparkling merchandise. In the scene that was done inside the store, Audrey Hepburn and George Peppard shock an uppity Tiffany’s salesman by asking to see something in the $10 range. (Says Audrey/Holly: “I think it’s tacky to wear diamonds before I’m forty.”) The salesman winds up showing the pair a sterling silver telephone dialer for $6.75—which they decline.

At the end of the 1960s, Tiffany’s appeared briefly in a very different kind of film, John Schlesinger’s gritty Midnight Cowboy, in a scene where hustler John Voight sees the disparity between the glittering storefront and the homeless man lying in the gutter in front of it. Cut to 1993, when Tiffany’s is again the venue for some serious shopping in Sleepless in Seattle, as Meg Ryan and her ill-starred fiancé Bill Pullman pick out a china pattern, and in Sweet Home Alabama (2002), there’s a memorable Tiffany’s moment when Reese Witherspoon’s boyfriend Patrick Dempsey leads her into a dark room, which turns out to be the diamond department in Tiffany’s. Minutes later he is on his knee proposing. She says yes.

Meanwhile, across the street at 718 Fifth Avenue, Tiffany’s chief rival Harry Winston has also made some romantic screen appearances, notably in Woody Allen’s Everyone Says I Love You (1999), when Edward Norton goes shopping at the famous jewelry store for an engagement ring for Drew Barrymore and the “My Baby Just Cares for Me” musical number ensues. Jennifer Lopez also “borrows” a diamond necklace from Winston’s to wear to the ball in Maid in Manhattan (2003). And, of course, both stores have their praises sung by Marilyn Monroe in her classic “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” turn in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), a number that Madonna famously ripped off some forty years later in her Material Girl video.

Visit www.tiffany.com.

Sony Pictures Building

When it debuted in 1984, this hulking Philip Johnson–designed skycraper was headquarters for AT&T. Drawing mixed reviews for its retro Chippendale-style cornice and praise for its spacious enclosed public plaza, the building was taken over by the Japanese electronics giant Sony in 1992 and now bears its name. A major player in the movie business, Sony bought the historic MGM lot in Culver City (Los Angeles) to headquarter its Sony Pictures division, which now also includes Columbia-TriStar. Recently, too, it made a bid for MGM itself. For movie lovers, a visit to Sony’s New York base of operations offers the chance to check out the Sony Wonder Technology Lab, an interactive museum, where among many attractions, it offers the chance to shoot and edit your own video.

Visit www.sonywondertechlab.com.

She was queen of the thrift shops, a kooky creature of vintage feather boas and antique schmatas. It made good copy for a while, but once twenty-two-year-old Barbra Streisand was well on the road to superstardom via Funny Girl on Broadway, platinum record albums, and a $5 million TV deal, it was time to clean up the act. Which is just what La Streisand did in the spring of 1965 on network TV in an elaborate nine-minute musical production number of “Second Hand Rose” in which she donned hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of glamorous high-fashion ensembles as part of her My Name Is Barbra special. The setting for this extraordinary media event was nothing less than New York City’s most exclusive department store, Bergdorf Goodman, and, besides furnishing the location, Bergdorf’s also supplied the outfits, including fabulous furs by the store’s famous resident fur designer, Emeric Partos, and hats by its not-so-well-known (yet!) in-house milliner, a young southern gent named Halston.

Not to be outdone by all the clothes and designers, Miss Streisand offered her own fashion tips to readers of the New York Times in a special on-the-set interview. Proving just how far she had come in the fashion department, Streisand had this to say on (1) boas: “A boa can be a great look if it’s kept simple, like with gray flannel and a hairdo very tight and slim. Curls and boas don’t go.” (2) Furs: “I used to hate mink but now I appreciate it for its solidity.… Lynx sheds.… I have Russian broadtail—it’s the most beautiful fur—but terribly perishable and I can hardly wear it because it’s so cold.… I’m mad for fisher.” (3) Fashion philosophy: “I like simple elegance, neat. I’d rather change my jewelry and have a few things and wear them all the time. A person is more important than clothes. A dress should fade out of sight, but greatly.” One wonders if that’s what she had in mind when she turned up at the 1969 Academy Awards in a see-through pants suit.

Besides appearing in the Streisand TV special, Bergdorf’s is also featured in the forgettable 1979 Ali MacGraw–Alan King film Just Tell Me What You Want, in a scene where the two stars get into a violent argument that spills out onto the street, and more memorably in Arthur (1981), where Liza Minnelli goes on a shoplifting spree. Look for the store, too, in Ridley Scott’s Someone to Watch Over Me (1987), Married to the Mob (1988), and Maid in Manhattan (2003).

Visit www.bergdorfgoodman.com.

When it opened in 1907, it billed itself as nothing less than “the world’s most luxurious hotel.” A mounmental eighteen-story French château, the Plaza was designed by Henry J. Hardenbergh, the architect who had been responsible for New York City’s fabled Dakota apartment building on Central Park West some twenty-three years earlier.

Of all Manhattan’s hotels, the Plaza is the city’s undisputed superstar as far as movies are concerned, and it’s no wonder since, in addition to being one of New York City’s most historic and handsome buildings, the Plaza enjoys an eminently photogenic setting. Not only does it have a fabulous fountain in its front yard, it has Central Park across the street and an ever-present lineup of horse-drawn carriages nearby to complete the postcard-pretty picture. The list of films, television shows, commercials, and print ads that have used the Plaza as a background is enormous. Among the more recent features are Hollywood Ending (2002), Life or Something Like It (2002), It Could Happen to You (the 1994 Nicolas Cage–Bridget Fonda remake), Metropolitan (1990), Big Business (1988), Crocodile Dundee (1986), Brewster’s Millions (1985), The Cotton Club (1984), Annie (1983), Arthur (1981), Prince of the City (1980), King of the Gypsies (1978), Love at First Bite (1978), The Rose (1978), Network (1976), The Front (1976), The Great Gatsby (1974), The Way We Were (1973), 40 Carats (1973), Puzzle of a Downfall Child (1970), and Funny Girl (1968).

And then, of course, there’s Plaza Suite, the 1971 film version of the 1960s Neil Simon play that’s set entirely in Suite 719 of the hotel. Four years earlier, the Plaza featured in another Neil Simon Broadway success turned Hollywood film, as the hotel where Jane Fonda honeymooned with Robert Redford in Barefoot in the Park. Further back in time, Hitchcock’s classic North by Northwest (1959) features a dramatic Plaza sequence in which Cary Grant is kidnapped from the hotel’s lobby. Before that, Twentieth Century–Fox booked Plaza rooms for the three out-of-town star couples vying for a plum New York City job in Women’s World (1954) and, when Ma and Pa Kettle Go to Town in Universal’s 1950 film, guess where they stay?

Dashing Cary Grant dashes through the Plaza’s lobby in North by Northwest, 1959

Other famous Plaza residents include Christopher Walken, who operated a drug ring out of his Plaza suite in King of New York (1990); Macaulay Culkin, who had the good sense to check in here when separated (yet again) from his parents in Home Alone 2: Lost in New York (1992); and Kate Hudson, as the archetypal rock groupie Penny Lane, who OD’d at the Plaza in the 2000 film Almost Famous.

Returning to the distant past, back in 1930, an early New York–made talkie called No Limit starred the famous silent-screen actress Clara Bow, and also featured the Plaza. A decade before that, Norma Talmadge’s By Right of Passage had a major sequence done on location at an actual charity ball being held at the Plaza. Playing a small role in this film was an actress friend of Miss Talmadge’s who later became a major Hollywood columnist: Hedda Hopper. The script for By Right of Passage was by Anita Loos, and the Plaza party that the film documented was hosted by the famed Elsa Maxwell.

Speaking of Plaza parties, one of the most spectacular ever to be staged at the hotel took place on Monday, November 28, 1966. The event was the gala Black and White Ball hosted by writer Truman Capote for Washington Post/Newsweek publisher Katharine Graham. The cream of Hollywood, Broadway, Washington, and New York City society turned up, and among the movie people on the guest list were Frank Sinatra and his then wife, Mia Farrow (who twisted the night away with Bennett Cerf’s son, Christopher), Claudette Colbert (who sat at an “exceedingly popular” table, according to the New York Times), Candice Bergen, the Sammy Davis Jrs., Marlene Dietrich (a no-show), Greta Garbo (also a no-show), the Henry Fondas, the Walter Matthaus, the Vincente Minnellis, the Gregory Pecks, Jennifer Jones, the Billy Wilders, and Darryl Zanuck. Men wore black dinner jackets and black masks, women turned up in black or white dresses and white masks. During the evening, Mr. Capote, whose Breakfast at Tiffany’s and In Cold Blood were turned into major movies, and who appeared in Neil Simon’s 1979 film, Murder by Death, spent a lot of time alone at the back of the ballroom just watching and delighting in his creation. At the time, Capote said that the black-and-white theme for his evening was inspired by Cecil Beaton’s costumes for the Ascot scenes in My Fair Lady. But movie lovers may wonder if Mr. Capote wasn’t also influenced by party-guest Vincente Minnelli’s spectacular black-and-white ball sequence in An American in Paris. Asked why he chose the Plaza for his gala, his answer was simple: “I think it’s the only really beautiful ballroom left in the United States.”