1975

“We thought they were pretty aggressive people and … they probably thought we were monsters. So we very quickly broke through that, because when you deal with people that are in the same line of work as you are, and you’re around them for a short time, why, you discover that, well, they’re human beings.” —Vance Brand

By 1972, the space race was winding down. The Americans had landed on the moon multiple times, and the Soviet space program had abandoned its moon program and shifted instead toward a new strategy of building space stations for research and exploration.

The Cold War was starting to “thaw out” politically as well. In May 1972, US president Richard Nixon traveled to Moscow to meet Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev. It was the first time that a US president had ever visited the capital of the USSR. The purpose of the mission was simple: to begin a new policy between the two world superpowers known as détente (a French word meaning “the easing of hostilities”). Nixon was moving US soldiers out of Vietnam, opening trade with the Soviets, and the two leaders were now going to try to start a period of cooperation rather than hostility.

One of the most visible examples of détente would be a joint US-Soviet space program known as the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. Both countries had space stations in orbit (the Soviet Salyut and the American Skylab) and were progressing in their exploration. The Apollo-Soyuz Test Project would involve a US ship and a Soviet ship docking in outer space in a symbolic expression of peace between the two countries. If that doesn’t seem like a big deal to you, keep in mind that a lot of US astronauts had flown jet fighters in combat against Soviet MiGs in the Korean and Vietnam Wars.

Display of the Apollo-Soyuz capsules docking at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington DC

The Apollo spacecraft would be commanded by astronaut Tom Stafford, and the Soviet Soyuz craft would be commanded by cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, the first human ever to successfully perform a space walk (EVA). Three Apollo astronauts and two Soyuz cosmonauts would move to a training facility in Houston, where they’d spend the next two years preparing for their historic mission.

Getting a group of people to work together and crew a spaceship was hard enough, but now you had five guys who didn’t speak the same language and were from two countries that had spent the last thirty years hating each other’s guts. For three decades, the United States and the USSR were one bad day away from incinerating Earth in a nuclear war, so you can imagine there might have been a little bit of pressure on these guys, considering that their mission was to serve as a beacon of peace between these two countries.

The Apollo-Soyuz mission crews

The first hurdle was for both crews to learn the other’s language. Tom Stafford was from Oklahoma, and he had a pretty hard-core accent, so the Soviets (who had studied English in school) had a tough time understanding him at first. Stafford spoke a little Russian, but not much. It also doesn’t help that the two languages don’t even use the same alphabets. Eventually, after weeks of working together, the two crews cobbled together a common language that they jokingly referred to as “Oklahomski.”

After two long years of training, simulations, and practice, the mission was finally ready to begin in July 1975. The Soviets launched their Soyuz craft from Kazakhstan, and seven and a half hours later the Americans launched an Apollo spaceship from Cape Canaveral in Florida. After two days in orbit, the two ships located each other and began the delicate docking procedure. Both countries were watching live on television; failure could have potentially been a bad omen for US-Soviet relations.

The Soyuz and Apollo spacecrafts linked up in Earth orbit on July 17, 1975. The Soviet crew went to the hatch and knocked for the Americans to let them in. Tom Stafford responded by yelling (in perfect Russian), “Who’s there?” The Soviets laughed, the Americans opened the hatch, and the two greatest space-faring countries on Earth were sharing a single spaceship for the first time in history. Two countries that were recently enemies were now shaking hands and hugging on worldwide television. It was the first step in what is now a concerted effort by all the countries on Earth to work as one and explore our universe together.

The cosmonauts and astronauts ate together and hung out in the ship for two days. They talked on the phone to Brezhnev and President Gerald Ford, exchanged presents, and told stories. Apollo commander Tom Stafford played a song he’d brought with him. He’d asked American country music star Conway Twitty to record his hit song “Hello Darlin’” with the lyrics translated into Russian, and both crews sat together and listened to it before they undocked.

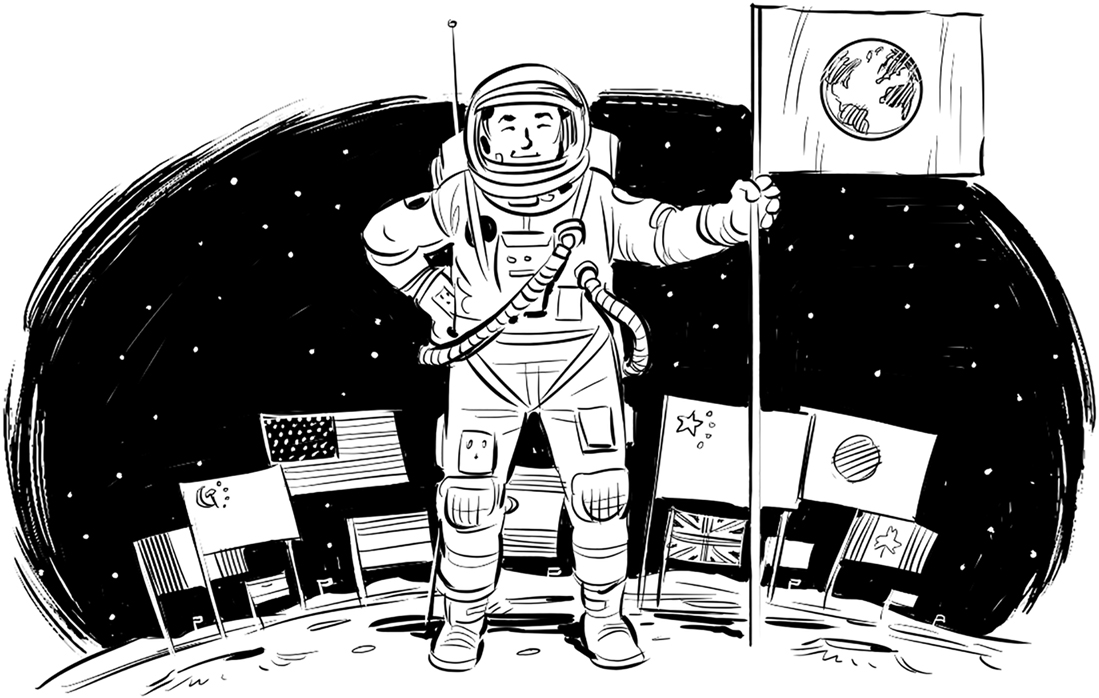

This was a momentous step toward peace between the United States and the USSR, but it was just the beginning of the world working together on space travel, exploration, and scientific discovery. More joint missions would follow, first to the Soviet space station Mir, and then later to the International Space Station, which was launched in 1998 from parts brought up by US space shuttles and Soyuz and Proton rockets from the Russian Federation. Nowadays, NASA, the Russian Roscosmos, and space agencies from Canada, Japan, India, and China all work together on countless missions to space for research and discovery.

A lot has happened since we put a man on the moon. The Berlin Wall fell, the Cold War ended, the Internet was invented, and gluten-free English muffins became a thing. Nearly fifty years after Neil Armstrong’s “One small step,” mankind has taken multiple giant leaps in science and technology: from the space shuttle program to reusable rockets, Mars rovers, and probing deep space in search of potentially habitable planets. Generations of scientists and innovators have been inspired by these brave pioneers of the Space Age. But the moon was not the end; it was just the beginning!

Astronaut Mike Hopkins takes a “space selfie” during an EVA from the International Space Station on Christmas Eve, 2013.

And we’re still only just getting started.