1942

“The rocket performed perfectly, except for landing on the wrong planet.” —Wernher von Braun

Around the 1920s, German engineers entered the scene, testing and developing their own rockets. They were intent on becoming the first in space. In 1927, three Germans—Johannes Winkler, Max Valier, and Willy Ley—founded the Spaceflight Society, an organization that would go on to foster many of the brilliant minds who eventually made spaceflight a reality. One of those brilliant minds belonged to Wernher von Braun, the man who would ultimately chart the conquest of space.

Von Braun with a model of his V-2

One of the most highly regarded rocket scientists to ever walk the earth, Wernher von Braun is the father of modern spaceflight and a man who dedicated his life to the pursuit of his goal. He earned a doctorate in physics for aerospace engineering from the University of Berlin. Inspired by Robert Goddard’s work in the United States, von Braun began to develop his own liquid-fueled rockets. When the Nazi Party rose to power in Germany, however, the Spaceflight Society was dissolved and civilians were barred from firing rockets. In order to continue his research, von Braun reluctantly joined the Nazi regime as the world geared up for World War II.

With the Nazi’s, von Braun developed the A-4 rocket, his first full-scale prototype. The A-4 was revolutionary. Von Braun’s singular motivation was to launch it into orbit, but the Nazis had something else in mind. The A-4 was renamed the V-2 and reclassified as a “Vengeance” missile.

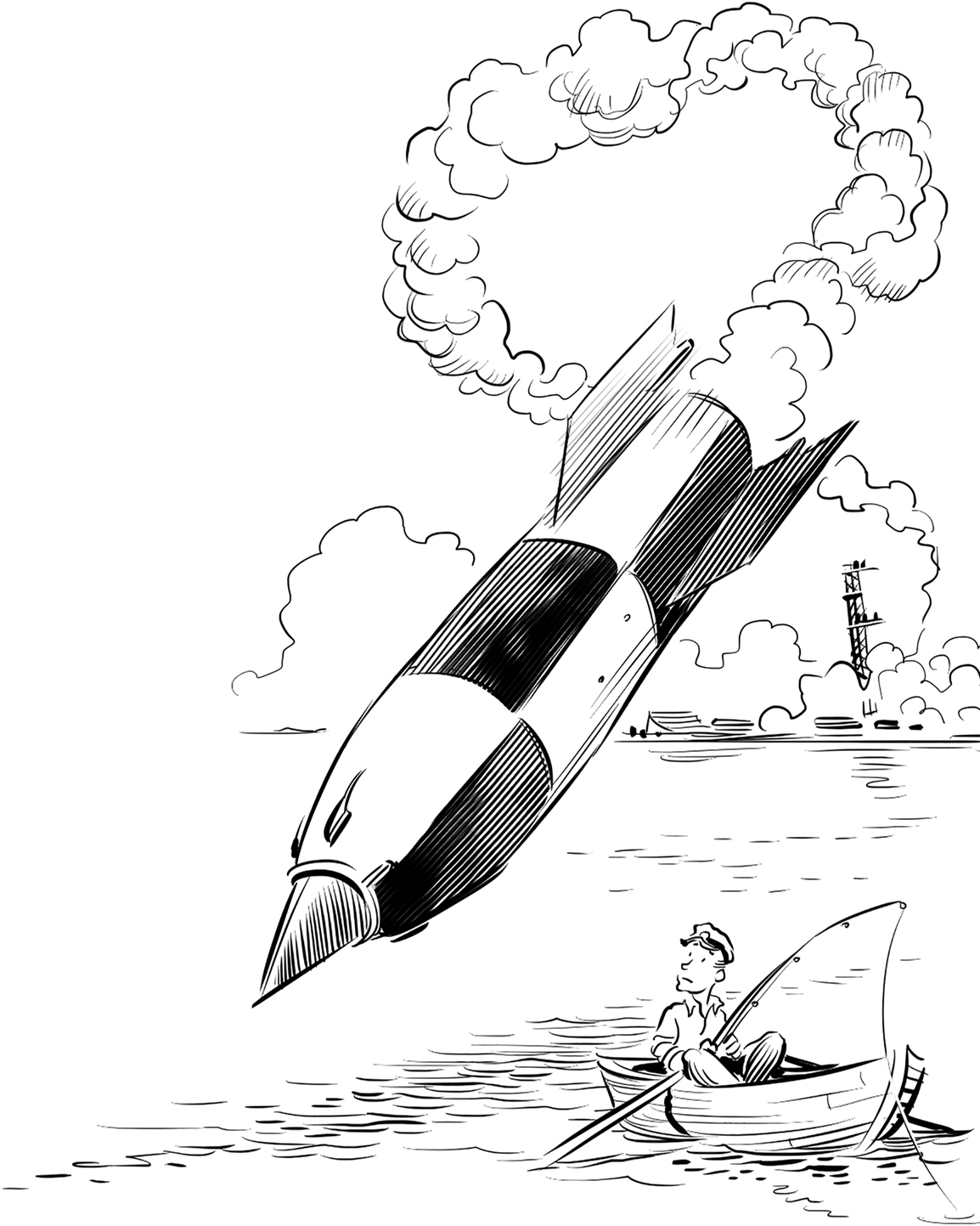

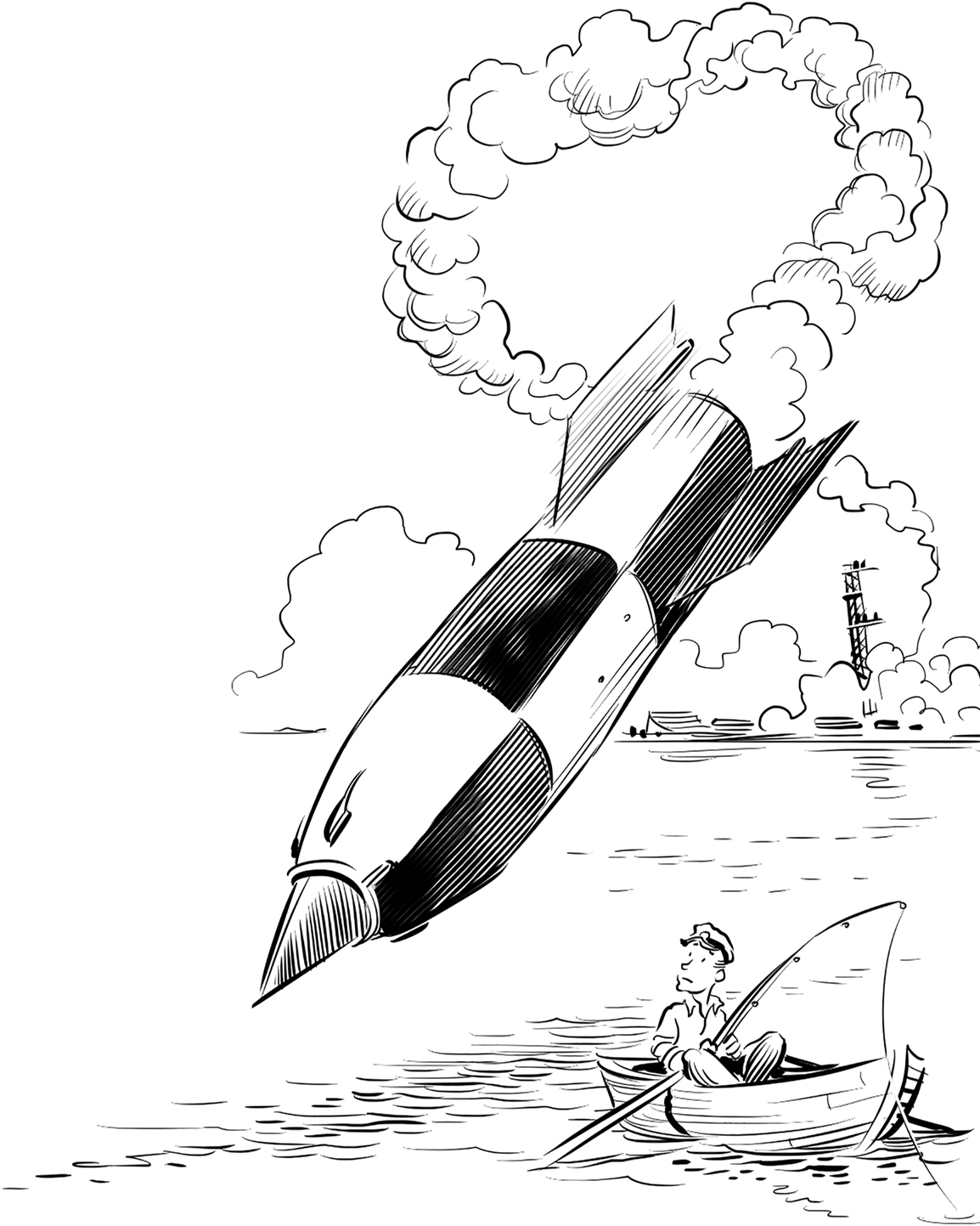

Von Braun’s V-2 looked more like a retro spaceship from a classic sci-fi TV show than a modern rocket. The sleek missile had curved fins and a rounded exterior. At nearly 46 feet tall, a wingspan of 11 feet, and weighing 27,600 pounds, the rocket was a sight to behold. The V-2 would become a prototype for the rockets of the Space Age that would soon follow. Nothing like it had even been attempted before, so of course there was a lot of trial and error—possibly more error than trial.

During initial tests, the V-2 endured every possible malfunction. In February 1942, the first test model slipped out of its restraints and fell two meters, smashing its fins. During the prototype’s second launch, the navigation system failed, sending it spiraling into the Baltic Sea before exploding. The third rocket’s nose broke off. Other test rockets flew off course, blew up in midair, or just fell over on the launchpad and unceremoniously exploded. In fact, there were so many problems that the Nazi’s suspected von Braun of conspiring to sabotage the rocket program.

It wasn’t until October 3, 1942, that von Braun had his first successful launch. The V-2 reached supersonic speeds and traveled 52 miles in the air. Adolf Hitler, however, was unimpressed by the expensive project. He dismissed von Braun’s momentous achievement as nothing more than an expensive artillery shell.

As the war waged on, the misuse of his rockets began to wear on von Braun. In 1944, he got drunk at a party and went on about how Germany was going to lose the war and all he ever wanted to do was send a rocket into space. The Nazi secret police arrested von Braun as a traitor, but he was later cleared of charges when the authorities realized that no one else understood rockets as well as he did.

Wernher von Braun was forced to continue his work on the V-2 program as Germany’s warheads were loaded and weaponized. To von Braun’s dismay, beginning on September 8, 1944, a volley of over 3,200 V-2 missiles were armed with explosive warheads and launched at cities and military installations in Great Britain and elsewhere. He wrote, “The rocket performed perfectly, except for landing on the wrong planet.” When the rockets landed in London, the governments of the world recognized for the first time the truly destructive potential of rocket engineering. But still, they ignored the potential for space travel.

As the war came to an end in 1945 and Allied forces closed in, Hitler ordered that all scientific research and development be destroyed. Von Braun and his fellow scientists weren’t ready to give up on their dream, and weren’t interested in becoming prisoners of war to the Allied forces. They hoped that they’d be able to use their expertise as a bargaining chip. Together they hatched a plan to escape to the Bavarian Alps, where US troops were advancing.

Germany was divided between the United States and its allies, one of which was the Soviet Union—a large communist state based in Russia that encompassed many current European and Asian countries. The United States and the Soviet Union emerged from WWII as the two most powerful countries in the world, and as soon as the war with Germany ended, new tension began between these superpowers. The Soviets gathered as many V-2 rockets as they could get their hands on, while the United States secretly imported as many German scientists as they could manage, including von Braun.