1958

“It’s a very sobering feeling to be up in space and realize that one’s safety factor was determined by the lowest bidder on a government contract.” —Alan Shepard

On July 29, 1958, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) into existence. Its mission: “to provide for research into the problems of flight within and outside the Earth’s atmosphere, and for other purposes.” NASA was created by an act of Congress, and it was a civilian entity rather than another branch of the military because Eisenhower wanted to ensure that the space agency pursued a scientific endeavor. He also didn’t want to make the Soviets nervous that this was a weapons program. The ulterior motive, of course, was to one-up them at their own game.

NASA absorbed the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA, the guys behind Chuck Yeager’s historic flight), along with resources from Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Langley Research Center, and the army’s rocket-research team. NASA’s singular goal was to put a man in space. It was the biggest scientific undertaking in America since the Manhattan Project.

Dr. Hugh L. Dryden, the former head of the NACA, made a video announcement to all his employees welcoming them to NASA and introducing them to their newly appointed administrator, T. Keith Glennan (you can watch a video of this on NASA’s YouTube page). Over the coming months, it was Glennan who really got the ball rolling, championing elegant simplicity and speed over sophistication. When kicking off the program, all he said was, “Let’s get on with it.”

Under Glennan’s direction, NASA united the nation’s brightest minds under one umbrella. Thousands of men and women from all backgrounds were integral to the mission. Decades before cell phones, home computers, or even pocket calculators, NASA employed human “computers”—a workforce of hundreds of female mathematicians who checked and rechecked calculations. One thing that set NASA apart from the Soviet space program when it came to human spaceflight was its commitment to a safety rate of 99.9 percent. The Americans were going to get to space, but they weren’t going to lose anybody to do it.

Christopher C. Kraft Jr. became NASA’s first flight director. He was given one simple assignment: “Chris, you come up with a basic mission plan. You know, the bottom-line stuff on how we fly a man from a launchpad into space and back again. It would be a good idea if you kept him alive.”

No pressure.

Chris Kraft tackled the problem head-on and created the basis for protocols that are still in use today. Before Mission Control was established in Houston, Texas, there was the Mercury Control Center in Cape Canaveral, and it operated on a low budget. It was a makeshift operation in which the most high-tech instruments the flight-control group had were corded telephones, mechanical clocks, and No. 2 pencils. Without the fancy computer readouts of later space missions, the Mercury team relayed information from other sites and kept track of everything manually. Radar and telemetry (flight information) readouts were processed by a massive off-site computer—the size of a building—that was slower than a home PC from the ’90s and had less processing power than an iPad.

People often forget that without NASA, we wouldn’t have GPS, cell phones, weather forecasts, Facebook, or the ability to watch live broadcasts from the far corners of the globe—all basic modern necessities that we take for granted. During its early years, NASA put the world’s first weather satellite into orbit, along with the first television satellite (Telstar) and the first navigation satellite (NAVSAT). Meanwhile, engineers at Langley Air Force Base in Virginia were hard at work designing and testing the latest high-tech spacecraft that would hopefully carry the first Americans into space.

The United States was finally making headway in the space race, but a lot of work still had to be done. Around this time, Edwin Diamond of Newsweek magazine wrote, “The first man in space? Most likely a Russian. A mission to Mars? The Russians won’t pass up the chance next year. The first man on the moon? He’ll be carrying a hammer and sickle.”

But what most people didn’t realize, however, is that the Soviets also had their fair share of failures; they were just really good at keeping them under wraps. In fact, many of them became declassified only within the past couple of years!

What people were hearing about, however, were the big successes in the Soviet space program. In 1959, the Soviets launched the first “cosmic rocket,” Luna 1, which missed the moon’s orbit (by 3,700 miles!) and drifted into deep space, but Luna 2 became the first man-made object to crash into the lunar surface. Luna 3 was the first spacecraft to photograph the dark side of the moon, and a few months after that, Venera 1 became the first probe to reach Venus.

Front page of the UK’s Daily Mirror as the Soviet’s success becomes internation news

The United States was struggling to keep pace, and finally, after months of extensive planning and reorganization at NASA, Project Mercury was a go. Named after the Roman messenger god, Mercury would be America’s first foray into human spaceflight. In January 1959, Project Mercury began its thorough search for a team of astronauts with “the right stuff.”

Before the Mercury program could take off, however, the Soviets made another historic achievement.

They beat the Americans to space.

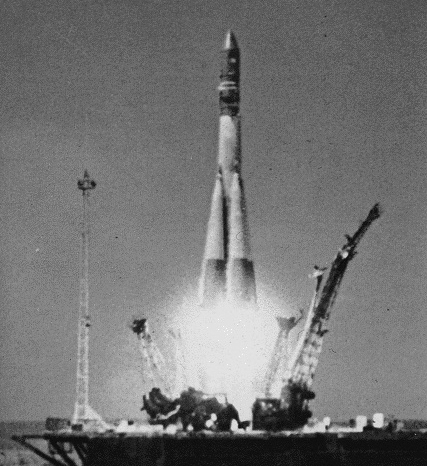

On April 12, 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin orbited Earth and made it back in one piece aboard the Vostok 1 spacecraft. The 108-minute flight had a minor issue on reentry that sent Gagarin spinning out of control, but he managed to eject and land safely. Upon Gagarin’s return to Russian soil, the leader of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev, congratulated him in person. “Let the capitalists try to catch up with our country, which has blazed the trail into space and launched the world’s first cosmonaut.”

It was another stunning triumph that rocked the world. Moments later, on the other side of the globe, at 5:30 AM, eastern time, NASA’s PR chief, Colonel John “Shorty” Powers, woke up to a phone call from a reporter. Powers’s groggy response was “What is this? We’re all asleep down here!” The following day, headlines read: SOVIETS PUT MAN IN SPACE. SPOKESMAN SAYS U.S. ASLEEP.

Vostok 1 sends Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin up to become the first man in space