1965

“The dream of yesterday is the hope of today and the reality of tomorrow.” —Robert Goddard

The United States and the Soviet Union had each put men into space—and, just as important, brought them back to Earth alive. But the moon was still 232,271 miles away, and no amount of pump-up speeches was going to get humanity any closer to its destination. That was going to take a lot of hard work, math, science, and experimentation.

In 1961, NASA recruited a second group of astronauts and went to work on a new spaceflight program: Project Gemini. The goal of this mission was to practice and learn as much about space travel as possible but to do it while still orbiting Earth. If something went wrong, it would be a whole lot easier to get home from Earth’s orbit than if the malfunction happened all the way out at the moon. Project Gemini was designed to learn about three major challenges that would face a possible moon landing. The first was whether a person in a space suit would be able to go outside his ship, maneuver around, and perform basic tasks, such as repairing the capsule in an emergency. The second question involved whether staying out in space for extended periods would negatively affect the human body. A moon mission was going to take a couple of days, and if zero gravity did weird stuff to a person’s physiology, that might be good to know. The third involved trying to dock two space vessels together while they were both in orbit, which, if possible, would open up a lot of options for planning future moon missions (during the Apollo missions, this technique would be used to reconnect the lunar module with the command module).

The Mercury capsule wasn’t great at maneuvering in space, so Project Gemini required a new spaceship. They created the Gemini capsule. Gemini was larger, designed for two crew members, but a bigger capsule didn’t mean these guys weren’t pretty squished in there. The ship itself was so small that neither crew member could even stand up during their mission, which doesn’t sound like a whole lot of fun when you’re stuck in one of these things for a couple of days.

The early missions were designed mostly to test the new ship. Gemini 1 and Gemini 2 were unmanned missions, and Gemini 3 took John Young and Gus Grissom up into Earth’s orbit. Gus Grissom named Gemini 3 the Molly Brown, from the Broadway play and movie The Unsinkable Molly Brown, referencing the fate of his previous space capsule, which wound up at the bottom of the Atlantic. Unlike Grissom’s Liberty Bell 7, the most notable thing to happen aboard Gemini 3 came to be known as the infamous “corned beef sandwich incident.”

One hour, 52 minutes, and 26 seconds into the mission, John Young pulled out a piece of “illegal contraband” that he’d smuggled aboard: a corned beef sandwich! “Where did that come from?” Grissom asked.

Young replied, “I brought it with me. Let’s see how it tastes.” They both took a bite. “Smells, doesn’t it?”

“Yes,” Grissom said with a mouthful. “It’s breaking up. I’m going to stick it in my pocket.” They quickly stuffed the crumbling sandwich away before the debris shorted out the space capsule’s sensitive equipment.

Disappointed, Young said, “It was a thought, anyway.”

“Yep,” Gus agreed.

“Not a very good one,” Young admitted.

Believe it or not, the corned beef sandwich incident launched a full congressional investigation! The associate administrator for manned spaceflight, George Mueller, assured Congress, “We have taken steps … to prevent recurrence of corned beef sandwiches in future flights.”

Clearly a historic moment for space travel.

Corned beef sandwiches aside, the Americans were making considerable headway toward their goal of being the first to the moon. But the Soviets weren’t sitting back and chilling, either. Things really heated up in March 1965, when Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov performed the world’s first space walk as part of the Voskhod 2 mission. Attaching himself to his capsule by a tether cord, Leonov opened the door of his ship, stepped out, and floated freely with nothing but his space suit to protect him from the freezing cold, airless vacuum of space.

News of Leonov’s space walk, also known as an EVA (extravehicular activity), came as a shock to NASA. It also came at an incredibly dangerous time, when tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union were coming close to a nuclear war. In 1965, the Americans and the Soviets were providing military and financial aid to opposing sides in the Vietnam War, with the United States supporting the democratic South Vietnamese and the Soviets backing the communist North Vietnamese. Both the United States and the USSR were fighting for any supremacy they could achieve.

So when Gemini 4 blasted off from Cape Canaveral on June 3, 1965, just three months after Leonov’s space walk, the stakes were about as high as they could get.

The Gemini capsules were propelled into space by the Titan II rocket, which is basically a gigantic missile that stood about ten stories tall. The Titan II formed the core of the US long-range nuclear-missile program, but for Gemini the engineers simply reconfigured a few things, removed the nuclear warhead, attached a Gemini capsule onto it, and then used it to blast astronauts Ed White and James McDivitt into space at a couple of thousand miles per hour.

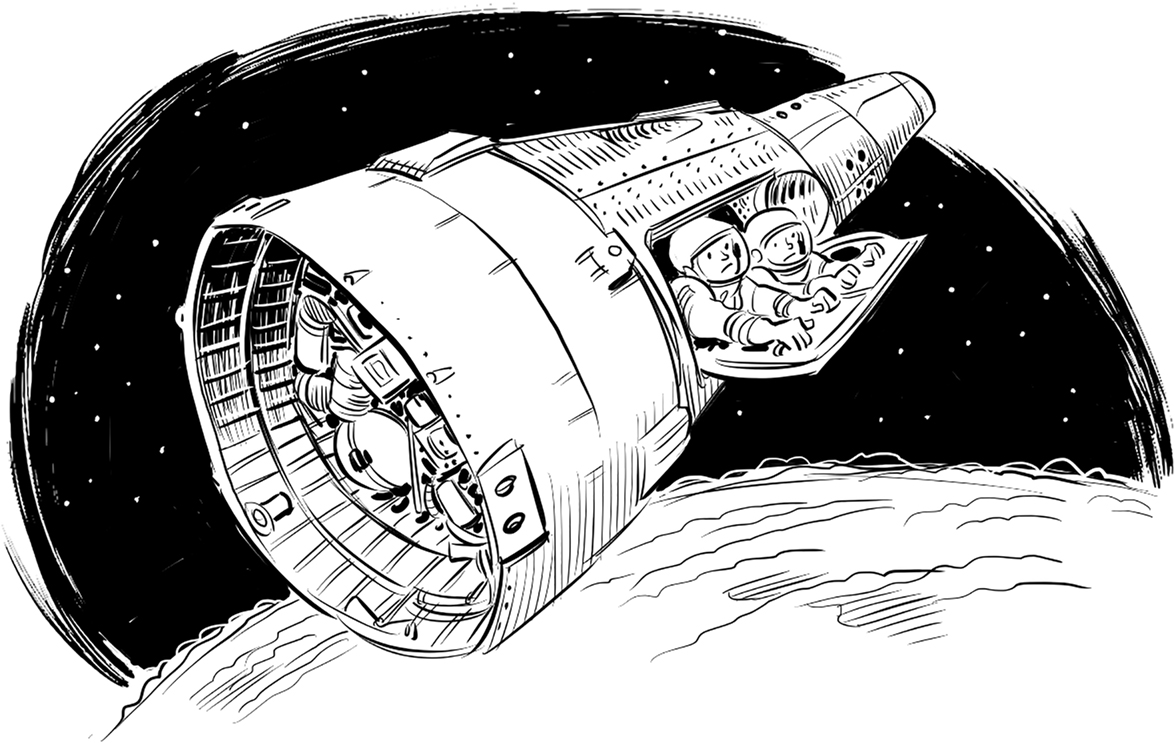

NASA monitored the mission from its brand-new Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas, as White and McDivitt began their preparations for the EVA. As Gemini 4 orbited more than 100 miles above Hawaii, McDivitt kept an eye on the flight controls while Ed White pulled the hatch open and ejected himself from the spacecraft with only a 25-foot-long tether hooking him to the ship. Everyone held their breath as White, an air force pilot who had logged over 2,000 hours piloting jet aircraft, slowly drifted toward the blackness of space. Then the radio transmission came in. White said, “I feel like a million dollars!”

Astronaut Ed White taking the world’s first “space selfie”

Ed White during his EVA

Zero gravity isn’t easy to move around in, so White tried to navigate using a remote control attached to an oxygen tank he had strapped to his chest. When he pulled a lever, O2 would shoot out of the tank (kind of like a jetpack) to move him around. Unfortunately, the tank wasn’t really all that big; it held only about three minutes of propulsion.

Because Ed wasn’t ready to come back, he just pulled on the tether to maneuver himself around the ship and keep hanging out in space. You’d have to be pretty brave to pull yourself around on the one thing that is standing between you and certain death, but you also have to be pretty brave to be an astronaut in the first place, so this makes sense.

After a 20-minute space walk, White finally came back to Gemini 4. But there was a problem—the hatch wouldn’t close!

Wearing big astronaut gloves, operating in almost complete darkness, Ed White and James McDivitt suddenly realized both of their lives were on the line. They pulled, fought, and struggled to get the hatch resealed. With that thing open, both men would burn to death on reentry to Earth’s atmosphere.

We have to imagine that the hiss of that hatch finally locking shut was one of the greatest and most relieving sounds those guys ever heard in their entire lives. Finally, they completed their mission and returned home in one piece.

The first American space walk had been a success. But that faulty hatch wouldn’t be the only problem the Gemini program would run into.

The next one was a doozy.