CHAPTER 3

Orville and Wilbur

1896

“The moment you doubt whether you can fly, you cease for ever to be able to do it.”

—J. M. Barrie (Peter Pan)

Wilbur and Orville Wright were brothers, born four years apart, and they were best friends. They were the sons of Milton Wright, a pastor for the Church of the United Brethren in Christ in Dayton, Ohio, and his wife, Susan. Milton was a loving father who’d grown up on the frontier and taught his children the value of self-reliance and hard work, but he was also a lifelong reader and kept an extensive library of literary classics, history books, and encyclopedias.

Wilbur and Orville Wright, circa 1876/1877

When Wilbur and Orville were kids, their father brought home a toy that sparked their imaginations: a small, primitive helicopter made from wood and rubber bands, based on a design by French aviation engineer Alphonse Pénaud. The brothers played with it until it broke, and then they built one out of stuff they found around the house and kept right on going. Even at an early age, they were hooked on the idea of building something that would fly.

Both boys were smart, capable, and determined, but they had very different personalities. Wilbur, the older brother, was soft-spoken, straitlaced, and generally stoic. He was remarkably intelligent, had a strong personal drive, and dressed in well-tailored suits. His younger brother Orville, on the other hand, was more outgoing and fiery. Orville grew a big, bushy mustache, played the mandolin, made homemade candy, and was often cheerfully optimistic and temperamental. In school, Orville was typically described as a class clown and a bit of a troublemaker. He even got expelled once! You wouldn’t think these two personalities would go together well, but Orville always listened to his older brother, and that helped keep things in line.

Wilbur did excellently in high school and was considering Yale for college, but his plans were dashed one fateful day when he was playing ice hockey and took a hockey stick to his face, smashing out most of his teeth, laying him out, and injuring him so badly he had to drop out of school to recover. Orville, worried about his brother, dropped out as well and never returned.

Despite never finishing high school, the brothers were well read, extremely practical, and inventive. They weren’t going to let something like not having a diploma keep them from succeeding. After running a print shop together (Orville was a big-time newspaper fan), the boys decided in 1892 to get into the bicycle business. Cycling had recently become a national pastime, thanks to the invention of something called the “safety bicycle.” Have you ever seen those old-timey bikes with the humongous front wheel and teeny-tiny back wheel? Those are called penny-farthings, and riding one isn’t easy at all. Plus it’s pretty easy to fall off them and hurt yourself (it’s like falling off a regular bike, except you fall twice as far before you hit the asphalt). So in the 1880s someone invented the “safety bike” with two equal-size wheels, and pretty soon everyone forgot that penny-farthings even existed. The Wright brothers saw an opportunity to work on something cool that they enjoyed, and to make some cash while doing it. So they opened a bike shop in Dayton, Ohio, just a few blocks from their home.

Business at the shop was going well for a couple of years until one day in 1896, when Orville fell ill from a brutal disease called typhoid fever. Nowadays typhoid is treatable with antibiotics, but back then antibiotics hadn’t been invented yet, and with Orville running a 105-degree fever, things looked really scary. Orville passed in and out of consciousness, usually waking up to either his brother, his dad, or his sister Katharine sitting at the foot of the bed watching over him.

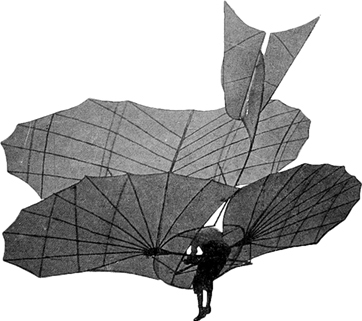

While Wilbur hung around watching over his sleeping brother, he happened to pick up a copy of McClure’s Magazine and read an article that would change the boys’ lives forever. It was about an eccentric German genius named Otto Lilienthal, who had dedicated his life to the goal of achieving human flight. Lilienthal had been an engineer in the Prussian Army, owned a company that made steam engines, and in his spare time made sweeping advances in glider construction and the mechanics of aviation. He published his calculations, Bird-flight as the Basis of Aviation, in 1889, describing concepts for a fixed-wing flying machine that sounded a lot like a modern-day hang glider. Two years later he put his theories to the test by building a glider out of muslin and wood and jumping off a huge hill he’d built in a park just outside Berlin.

Otto Lilienthal’s glider

Amazingly, it worked—Otto soared through the air. Sure, he didn’t have a ton of control over it, but he kept improving his designs, and over the next five years he flew more than two thousand times with eighteen gliders. Thanks to the invention of photography, pictures of Otto’s flights made their way across the world and inspired hundreds of men and women to follow in his footsteps—including Wilbur Wright as he sat in a dimly lit room in Dayton, Ohio, reading tales of Otto’s exploits to his sick brother Orville.