Moriyama is really a disgusting person. When he was in Matsumoto he used to come into my room. I’d strongly object, telling him that I have a maid to take care of my needs. Then he’d eat my leftover meals and fruits, saying it was a waste to throw these away. Sometimes he tried to get me interested in him by talking about the revival of China’s imperial system.

“I leave my life with you,” Moriyama told me.

“I have no use for anyone’s life,” I replied, brushing him off.

—KAWASHIMA YOSHIKO

Naniwa was perhaps correct in trying to keep the boys at bay, since the youths roaming about his house repeatedly proved themselves inadequate candidates for any kind of association with Yoshiko. While Naniwa attempted to exert control, stories about the turbulence that these hooligans stirred up in his residence made their way outside. The gossips were delighted. On the streets, conversations touched upon China, Japan, boyfriends, suicide attempts, and hair, but it’s safe to assume that no one commended Naniwa’s skills as a parent. All could see the conclusive proof of his colossal incompetence in raising his daughter, a child-rearing failure stemming from the same flaws that had doomed Naniwa’s other projects—explosive emotions and faulty assessments of events taking place around him.

First came the young man Moriyama Eiji, better known by his sobriquet Yamatomaru. He was a member of a violent gang of fanatic nationalists, League for the Prevention of Communism, which saw Communism as a grave threat to Japan and vowed to eradicate all traces. Dissatisfied with the Japanese government’s mass roundups of Communists, Moriyama’s group disposed of these enemies in their own way, along with other proponents of “dangerous, foreign ideologies.”

Already well-known to the police, Moriyama took part in an assault on prominent statesman Gotō Shimpei, who had come out in support of a conciliatory policy toward the Soviet Union. Moriyama was imprisoned for a time but begged Naniwa to take him in after his release. Naniwa agreed, saying that he “could see a pure side” to Moriyama, who soon proved the folly of this assessment. A dangerous presence in love as well as in politics, Moriyama eventually decided to whisk Yoshiko off, to rescue her from Naniwa’s bullying. He saw her being roughly treated and bragged about his challenge to Naniwa: “I said to him, ‘If you want to hit a lovely young woman, especially one from a foreign land, I suggest you hit me instead.’”

A brawl ensued with an incensed Naniwa, who finally understood the peril of letting this “pure” disciple anywhere near his residence. Yoshiko, for her part, heard about Moriyama’s intentions and took to her bed with a high fever. Far from reciprocating Moriyama’s affection, she rejected him as her savior. “He only has to look at a woman to do something bad,” she told one of the ever-present reporters. In case Moriyama had not understood her drift, she went on to elaborate. “I don’t care what kind of violence he’s planning in order to take me away, but I’ll die before leaving with him. I have obligations to my father here and definitely won’t be going anywhere.”

Moriyama, rebuffed but still ardent, went public with his love story, which the newspapers accorded extensive coverage for some days. He claimed that Yoshiko had become so upset by this episode that she attempted to kill herself with an overdose of morphine. According to Moriyama, he came to her rescue by sucking the drug from her lips.

Next was Yoshiko’s entanglement with Iwata Ainosuke, another of Naniwa’s thuggish acolytes. Also a violent and fanatical ultranationalist, Iwata was the chief of the Patriotic Society and had just served a twelve-year jail term for aiding the assassin of a high-ranking Foreign Ministry official. This official had come out against the establishment of a separate state, under Japanese control, in Manchuria and Mongolia, and he thereby enraged those Japanese in favor of aggressive moves in China. The official “was murdered in a spectacular gesture of protest by a young man who then seated himself on a map of China and committed hara-kiri so skillfully that his blood poured out over Manchuria and Mongolia.”

Fresh from jail, Iwata sought to marry Yoshiko, but she became so agitated at the prospect of another imbroglio that she again declared that she would end her life. Once she expressed a wish to die, Iwata obliged by giving her a pistol. She shot herself in her chest, but survived.

“I didn’t think she’d really do it,” Iwata offered.

Finally there was Lieutenant Yamaga Tōru of the army’s Fiftieth Regiment, who was Yoshiko’s first decent suitor. He brought Yoshiko another kind of humiliation. Nine years older and fascinated by China, Yamaga regularly visited Naniwa’s home to practice his Chinese with Yoshiko’s brother, who also lived there for a time. Yamaga stayed at nearby Tsuta Hot Springs, and Yoshiko would stop off to see him when she went to bathe there. Everyone at Tsuta Hot Springs thought that the two might marry, and her brother also took note of their intimate chats.

Rumors about this friendship began to circulate and eventually reached Naniwa, who, predictably, became furious. Since nothing in Yoshiko’s life then or afterward got settled without a public exposé, the local newspaper invaded her privacy again on November 21, 1925, by running a story about her engagement:

Chinese the Catalyst for Yoshiko’s Marriage

Love Develops with Lieutenant from Matsumoto’s Fiftieth Regiment

Yamaga, realizing that such newspaper reports would damage both Yoshiko and himself, promptly issued a denial. The next day, November 22, the headline read,

Story About Yoshiko’s Marriage Causing Much Trouble, Says Yamaga, Who Denies Account

Kawashima Also Cites a Misunderstanding

In the accompanying article Yamaga made his refutation more emphatic: “This has no basis in fact. I’ve only met her once.”

Naniwa, who was also interviewed, indicated that he lacked essential information, and, in an effort to push his daughter’s reputation in another direction, he told the reporter that Yoshiko was off at knitting class. “If she were interested in a certain Mr. Yamaga, Yoshiko would have told me. And, of course, if the person in question were someone outstanding, I would not be against her marrying.” With this vague, cool comment, which mustered up the flavor of a vigilant father concerned about his daughter’s friendships, the message was clear: Naniwa was not going to allow this relationship to proceed. Another remark from Naniwa takes on significance because of what happens next: “Yoshiko has an interest in matters like the problems in China and Asia and aspires to be like that mannish Western Joan of Arc. So she has characteristics that make her unsuited to the life of an ordinary woman.”

Even a more emotionally hardy young woman would have been crushed at being publicly brushed off by Yamaga and despondent about Naniwa’s rejection of her beau. In addition, Yoshiko had been demoralized by constant gossip about her, an especially galling development to someone who did indeed have dreams of matching the dedication of Joan of Arc. Then there are the rumors about her being raped by Naniwa, which would have taken place around this time if in fact it did occur.

No wonder Yoshiko declared around this time, “I’ve had all this trouble because I’m a woman.”

*

Yoshiko soon had most of her hair cut off.

“I don’t want to talk now or in the future about what went on in Kawashima Naniwa’s house,” Yoshiko declared later, issuing what may be a veiled allusion to a sexual assault. “Therefore I also don’t want to write too honestly about what happened to me when I was sixteen. But even today I cannot forget the night … when I decided to cease being a woman forever.”

It was in the November 27, 1925, edition of the Asahi that Yoshiko made her first appearance in a severe buzz cut, wearing a boy’s university uniform that presumably belonged to her brother. The transformation is stunning, for the photo shows what now looks like a young man with too much in the way of jaw and ears—and very short hair.

The stir caused by this haircut was far-reaching, wrecking any illusion of the Sino-Japanese bonding between Yoshiko and Naniwa that he had boasted about. In the future, her male hairstyle would mark her, merely a catchy trademark to many, but perhaps also a serious reflection of her true identity. Later, Naniwa’s side complained that too much of a fuss had been made about Yoshiko’s hair since it was merely the result of her going to get a haircut but ending up scalped by mistake. Anyone who’s had a bad time at the hairdresser’s will find this explanation insufficient for a haircut gone so wrong. No, Yoshiko wanted to become a man, and the photo proves that she succeeded.

She later wrote that she went off to have her hair cut on the evening of October 10, 1924. That morning, she claimed, she had dressed herself up as a typical Japanese young woman, in a kimono and with her hair in a traditional female style. Then she posed for a photo in a field of blooming cosmos flowers, to commemorate “my farewell to my life as a woman.” At forty-five minutes past nine that night, she writes, she went to a barbershop for the haircut. “I’ll leave it to you to imagine how angry and surprised my adoptive mother and father were.”

Biographers have scoured the record for verification of the date and photograph, even going so far as to determine when cosmos bloomed in Matsumoto that year. Recent researchers have concluded that Yoshiko was off by thirteen months and actually went to the barbershop on November 22, 1925, the day the newspaper published Yamaga’s repudiation of their romance.

Five days later, that startling photo of her with her crew cut appeared in the Asahi, and the headline covered a lot of territory:

Kawashima Yoshiko’s Beautiful Black Hair Completely Cut Off

Because of Unfounded “Rumors,” Makes Firm Decision to Become a Man

Touching Secret Tale of Her Shooting Herself

Not only had she cut her hair and borrowed her brother’s clothes, she had also adopted a man’s rough style of speaking Japanese. “On the evening of the twenty-fifth … ,” the Asahi article begins,

a handsome youth with a shaved head was found standing in a Chinese restaurant in Matsumoto wearing a Waseda University uniform and high geta clogs.

“Hey, waitress, get me a drink,” the youth demanded in a stern voice, going on to get the old man beside to share some rounds.

“You better eat more,” the old man said, “and put on some muscle, or you’ll shame those sturdy geta you’re wearing.”

“I don’t like Chinese food,” the uncouth youth replied, laughing.

Although Naniwa could not get himself to issue a public statement about Yoshiko’s haircut, this did not stop the journalists from clamoring for answers. Instead of Naniwa, Yoshiko came forward with a sad explanation about why she’d suddenly changed herself into a man and taken the man’s name Ryōsuke. In this explanation, Yoshiko’s confusion about her own emotions is evident; after all, she is trying to fathom what she herself does not yet understand. Yoshiko struggles to be honest but at the same time she does not want to reveal too much. She struggles also to express her feelings in a manner that will be acceptable to the newspaper’s many readers. The result is obfuscation in one sentence, followed by truth in the next, and back again.

“Please forgive me for causing all of you only worry,” begins her statement, which was published two days later in the Asahi. “I now realize that all this has come about because of my tomboyish ways, my wish to fool around all the time. I promise to behave in a circumspect manner from now on, so please forgive me.” Such an analysis would have been palatable to her Japanese public, who appreciated such polite regrets, and Yoshiko goes on to recount what was already common knowledge: her womanliness had caused her no end of trouble. She says that men fell for her without being encouraged in the slightest. She’s been misunderstood, her playfulness taken in the wrong way. She knows that these uproars will continue in the years to come if she doesn’t change. And since she doesn’t want to get married, she’s chosen to become a man.

Up to this point, she is cautious, her motives restricted to keeping the boys away, but as Yoshiko continues, more seems to be at stake. Her next statements, surprising for their clarity and boldness, surely were included because they expressed her true state of mind. “I was born with what the doctors call a tendency toward the third sex, and so I cannot pursue an ordinary woman’s goals in life. People criticize me and say that I am perverted, and maybe they’re right. I just can’t behave like an ordinary feminine woman.” Here Yoshiko seems to express a wish not only to protect herself from male admiration by cutting off her hair but also to actually be a boy, a man, male.

Read today, the statement would be considered a sincere expression of the discomfort she felt living as a woman, to be taken very seriously. But Yoshiko found herself in Japan in 1925 and could not hope to make the kind of biological and legal changes that are now possible. And so, after seeming to move in one direction, Yoshiko retreats. Back to soothing the Japanese public, she says that she wants to take on a man’s role for strictly practical reasons, to accomplish the things men can achieve, like improving the lot of her people. “Since I was young I’ve been dying to do the things that boys do. My impossible dream is to work hard like a man for China, for Asia. I want nothing more in this world than to throw my whole life into working for the nation.”

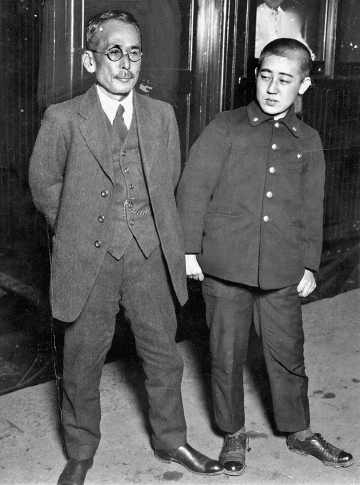

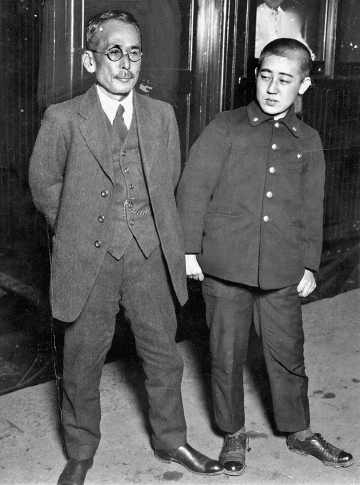

Naniwa and Yoshiko at Osaka Station just after her haircut, December 1925 The Asahi Shimbun/Getty Images

In years to come, Yoshiko’s actions would continue to be marked by such contradictions and distress. Sometimes she flaunted her love affairs with men, and at other times, dressed in severe male attire, she introduced a female member of her household as her wife. But whatever she did, she took care to keep her behavior within a range that was then socially and politically permissible in Japan: she switched back to a woman’s role when necessary and repeatedly invoked the image of Joan of Arc.

For the most part, Yoshiko’s Japanese biographers have not attached great significance to her proclamation about becoming a man. After all, she was a flamboyant character, not given to shying away from provocative acts, and the biographers view her fondness for men’s clothing and language as just another performance. They point to the fact that the Japanese were already familiar with women dressing as men, having been exposed to so-called modern girls, who cut their hair short and wore Western-style clothing to demonstrate their liberation from ancient rules about female behavior. Then there was the all-female troupe Takarazuka, with certain actresses specializing in men’s roles and thrilling their many fans.

Still, it appears clear that there was more to Yoshiko’s assumption of a male identity than just a desire to playact or be the center of attention. Her public remarks can be seen as her wish to tell of something deep within her, a need to show what was real. She had endured a miserable childhood, cut off from her family in China, and was left alone much of the time or in the company of Naniwa and his male disciples. Since her early years, she had made certain choices plain: she had shown a strong tomboyish nature and an inclination to use male language. From this time forward, she would use this masculine-style Japanese regularly and often appear in public in her male clothing, which for those times was an extraordinary decision.