An ordinary person would probably think twice about living in a free way. But Yoshiko was not at all afraid to grab such a life for herself. The public, which likes oddness, turned her into a hot topic, at times laying her down on a cutting board, making a meal of her, and adding decorations. It seems as though she had already been made into a legend during her lifetime.

—WATANABE RYŪSAKU

In April 1933, Muramatsu Shōfū’s novel The Beauty in Men’s Clothing, which had first been serialized in the magazine Fujin kōron, came out in book form in Japan. Yoshiko added to the buzz surrounding the publication by returning to Tokyo soon after. With the stories about her heroism in Rehe fresh in the public’s mind and the splashy release of a book about her, Yoshiko enjoyed the greatest celebrity of her life. She was a natural in the bright light, delighted and talkative, aware that a properly dignified media star should remain aloof but unable to stop herself from basking in the attention.

Only later would she understand how much damage she did to herself during this period. In fact, her return to Japan and the publication of The Beauty in Men’s Clothing marked the high point of Yoshiko’s fame but also the start of her slide to ruin. She would live for fifteen more years, be a darling of the journalists on numerous occasions, and issue her opinions on the day’s major events. But her usefulness to Japanese military officials had peaked, and increasingly she annoyed them.

In addition, the portrait of herself that she fashioned with so much pleasure at this time could not be effaced, and her own exaggerated descriptions of her military triumphs were used as evidence of her betrayal of China at the postwar trial. “My whole life has been formed by false gossip about me,” she complained in the first sentence of a confession she wrote in prison, “and I will die because of false gossip about me. This has been the case throughout my life.”

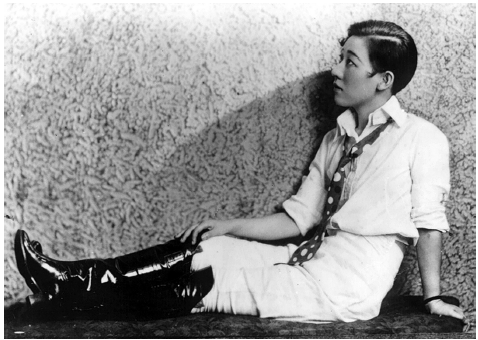

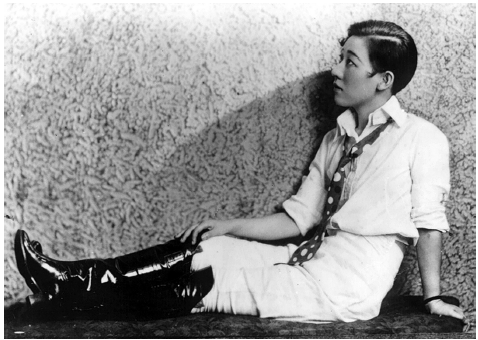

Yoshiko in a celebrity pose The Yomiuri Shimbun

Yet her grand-niece Shōko, who has reviewed Yoshiko’s various statements, disagrees. “Perhaps, as these words suggest, unverified reports were used as evidence and led to her death sentence, but perhaps this was simply her own fault.”

In one splashy media event during the 1933 trip, a Fujin kōron correspondent tracked her down at Tokyo’s Manchukuo legation, where she was staying, and obtained “exclusive” rights to her version of recent events. “Up to now,” the correspondent noted, “there have been various third-person accounts describing her feelings, but this time she herself has relied upon her own pen and written these words.”

In her personal essay “I Love My Homeland,” Yoshiko shows that she has returned to Tokyo as a Chinese. Childhood in Japan a memory, she adopts the stance of a thoroughly Chinese citizen whose loyalties are obvious and unshakable. This embrace of her Chinese origins marked another of her transformations, which continued to fascinate her Japanese readers.

Yoshiko’s minor or nonexistent achievements in battle had not stopped the shower of accolades that gave her credit for slaying “bandits” who wished to destroy Manchukuo and for “liberating” Rehe. So intense was the coverage that even she felt moved to object. “I led these troops and rode around to every corner of Rehe,” she writes, in a rare moment of modesty, “but compared with what I actually did, I got ten times the publicity. This was totally embarrassing.” Having acknowledged her small contribution, Yoshiko goes on to boast about her importance. She seeks the tone of a war-weary general, Grant at Appomattox say, satisfied in victory but melancholy about the bloody folly of war.

The photo on the article’s first page catches her in shorts and sneakers at the entrance to the Manchukuo legation, where she is relaxing after boxing practice. Another photo further on shows her wearing boxing mitts, working out at a punching bag. Her physical fitness established, Yoshiko shares details about her experiences as a warrior. She wants the magazine’s readers to understand that she fought, not for her own glory but to bring “happiness to the thirty million people of Rehe.”

She remembers the worshipful crowd that saw her off to battle—there were barbers, dance hall girls, gang members (“the good kind”), public officials, army men, the wives of Manchukuo ministers. Although the women wept as she departed, Yoshiko managed to smile back in return. This cheerfulness was only for her public, as joy was far from her heart. “In leading troops and going off to battle, I was not the slightest bit proud, nor did I rejoice.” She could not forget that her mission would end in many deaths. “As a poem from your country states, ‘Those who inflict wounds, and those who are wounded, take note! These are all the same human beings from the same country.’”

Yoshiko goes too far—at one point she claims that her troops made it possible for the Japanese army to enter Rehe without facing any opposition—but she sounds believable when at last detailing her reactions to what she has seen in Japanese-occupied China. She has in the past been absorbed in her luminous self, charging across China, without a glance at the devastated landscape. But in this essay Yoshiko shows that she has finally taken in the scenery. She saw all of it—slaughter on the battlefield, as well as the terror of the civilians, their lives crushed in the ongoing bloodbaths.

She tells of her horror—which would deepen as the war progressed—at the ruin the Japanese invasion has brought to China’s villages. “They are suffering in hell compared with what your Japan is going through.” Far from the dance halls, Yoshiko saw hopeless farmers desperate for food and clothing. In particular, she feared for the orphaned children. “I thought I heard a child crying and couldn’t ignore it. I had my soldiers go out to look, and finally they came to me carrying a young child. … Even though I was going off to battle, I couldn’t leave the child behind.”

With these outpourings, Yoshiko throws herself into the middle of China’s upheavals and seems to look over at Japan, where she had grown up, from a distance. She presents herself as a wise ambassador, one familiar with both China and Japan, who seeks to inform her Japanese readers about the true situation. Aware that she must be careful, she first expresses gratitude to the magazine’s female readership for the Japanese army’s help in Manchukuo.

I speak to you intellectual women from the Japan I love. Manchukuo, bolstered by the strength of Japan’s properly disciplined, deeply empathetic army, is gradually maturing into a fine country. Together with the people of Manchukuo, they are trying to develop Manchukuo’s natural resources and build a paradise beyond what humankind has ever known.”

That out of the way, Yoshiko shifts to less agreeable observations.

While there are Japanese whose inherent good nature impels them to make such touching efforts, we cannot deny that mingled among these are also bad Japanese known as “China rōnin.” They are also Japanese, and for the people of Manchukuo, it is a sorrow to have to think of them as Japanese. I spent my youth growing up in Japan. I understand the intrinsic virtues of Japan. Japan has done me many favors. So I cannot believe that these people are really Japanese.

She was not alone in being repulsed by the rōnin, who had come to be seen as a bunch of lawless thugs, roaming about China at will, forming vigilante gangs or tormenting Chinese as they liked.

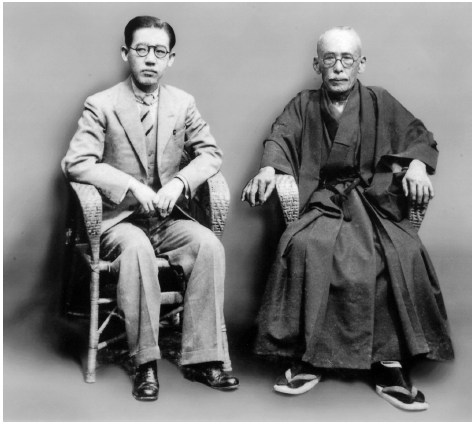

Yoshiko and Naniwa Courtesy Rekishi no Sato

In this essay, Yoshiko shows some restraint, but as the years passed, her comments about the Japanese in China grew more caustic and outraged. The Japanese army, which had been eager to make her their celebrity collaborator, came to regret the wide following they had helped her build. Her criticisms were a mere nuisance at the beginning, but as she grew more forceful in her denunciations of Japan, she became a louder subversive voice.

It was then that Japanese officers made plans to eliminate her.

*

In her heyday, Yoshiko was not only in Japan trying to spread the word about the war, she also went to China, where she lived it up in Manchukuo. The Japanese had still not determined whether she was an asset or a threat, though this decision would soon be made. For the time being, Yoshiko could move about Manchukuo freely.

In a magazine article published after Yoshiko’s death, the European lawyer Thomas Abe takes up her story in Harbin, where he helped her enjoy her fame and her money. Abe, whose name suggests Japanese ancestry, had just completed his law studies in Paris when he read about the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931. His interest piqued, he soon traveled to Harbin, where he established a law practice among the large Russian community there.

“It was a time when educated Russians could speak French. My office thrived.” His reputation soared when he won a case involving a White Russian doctor blamed for the death of a beautiful young Russian Communist patient during a hemorrhoid operation. Abe’s legal expertise seems less formidable, however, when he claims that he did not realize that the Japanese army had ignored the law in creating Manchukuo. “I shamelessly showed off my knowledge of legal theories, but only those that applied to the cultural centers in the heart of Europe.”

Abe says that he and Yoshiko were well suited, since his triumph in the hemorrhoid case had brought him a flashy renown that could compete with hers. They became intimates when she came to Harbin on behalf of a Manchu chief’s widow who sought compensation for her late husband’s property, which had been confiscated by Japanese railway authorities. Yoshiko planned to use her influence to assist the widow and also get a big cash reward for her efforts.

“She stayed at the splendid Modern Hotel,” Abe writes, “which was owned by a Russian. She joined two of the best rooms together and had her meals in the middle of the large dining hall. Several tables were joined together, and she would invite dozens of people over as guests. She’d have them play her favorite music and set herself up at the center of the table, which was full of flowers. Really she dined like a queen.”

As a token of “respect” for her efforts on behalf of the Manchu chief’s widow, Yoshiko received twenty thousand yen from the Japanese branch manager of the South Manchurian Railway, one of Japan’s sprawling, pervasive enterprises in China’s Northeast. She next devoted herself to spending this money as quickly as possible, with Abe’s help. Abe says that he was not in love with Yoshiko but found her company agreeable; obviously he also found it agreeable to live with her in grand style. The couple also went together to Changchun, where they again stayed in luxurious quarters, the same room Yoshiko had shared with General Tada Hayao. Her need for money constant, Yoshiko sent her assistant, Chizuko, out to get some from Manchukuo’s finance minister, but he refused to hand out anything unless Yoshiko turned up in person.

“That kind of money I don’t need,” she said and obtained cash from the more accommodating hotel.

Yoshiko boldly sat on Abe’s lap while riding down the streets in a car whose inside light was on, making them visible to passersby. “You’re just a high-class whore! “someone shouted at Yoshiko, but she didn’t get flustered. Dressed in gaudy Western clothes with a ribbon in her hair, she made an appearance at the Monte Carlo Dance Hall, and once she started dancing “like a butterfly,” she did not stop. The owner put a sign outside announcing “Kawashima Yoshiko is now here,” and curious crowds swarmed in to have a look.

Abe tries to show that Yoshiko was no obsequious ally of the Japanese military. In fact, Japanese authorities were as confused as anyone about which side she was on; they considered both Yoshiko and Abe suspicious characters and tailed them everywhere. “She knew too much about the inner workings of the Japanese military and looked upon them with contempt. … She was famous, and I also had a very flamboyant existence among the Russians. So of course the army did not look upon us favorably.”

Then there was Yoshiko’s thoughtful, beguiling personality that so enchanted Abe. “Sometimes when she felt like it, she went out wearing a general’s uniform. Her dressing as a man, which was like her trademark, was not at all unpleasant. She was no different from the Takarazuka actresses who, even though they’re not on stage during the day, dress like men when they go out. … When the two of us were alone together in our room, she was very feminine, very considerate of me. If she thought that I was bored, she’d put on the record of her singing Mongolian songs, whose music and words she had composed herself —‘If your long eyelashes are a forest, your moist eyes are a stream …’ After that she’d recite some poems that she liked. Even today I remember her voice.”

Abe also witnessed a more poignant scene when he accompanied Yoshiko on a visit to the Japanese army lieutenant general Tsukushi Kumashichi, with whom she had a close personal relationship.

“To tell you the truth,” Yoshiko said to Tsukushi, “I am now thinking of going to France or Germany with this man. So I’ve come to ask you for some vacation time.”

In his response, the general acknowledged the pathos of her precarious existence. “I think that’s a good idea. There’s nothing to be gained from always being at the beck and call of the army.”

A European journey would require a lot of money, for, once she went, she would probably not come back. Unable to collect sufficient funds, Yoshiko instead traveled in style to closer destinations. Abe tells of their departure from Harbin:

That morning many people came to see us off at the station. Even members of the military and the Special Higher Police, the same ones who had recently viewed us as enemies, came to see her off with flowers, sad to see her go.

By complete coincidence Yoshiko bumped into the branch manager of the South Manchurian Railway, and so she asked him, “Tell me, do you have a special compartment available? I’ve never ridden in a regular compartment.”

She was trying to coax him into giving us a VIP car. The branch manager rushed around to ready a special compartment and then ushered us in. Next she gestured to him from the deck of the compartment, pointing to her pile of luggage close by on the platform.

“Those are my bags. Could you quickly bring them in here?”

There were no redcaps around, and the departure whistle had sounded. Since Harbin was dependent on the railroad, this branch manager was like the lord of the city. But he served as her redcap and brought the luggage into the compartment.

Kawashima Yoshiko employed this same style in coaxing a hefty amount of secret funds out of the commander in chief and the head of the General Staff.