No, rather than merely saying that her situation was insecure, we should rather see her as having been thoroughly hounded out of her former position. Yoshiko, who had a sense of all that had gone on behind the scenes during the Shanghai Incident, became a nuisance to the military after the Sino-Japanese War began.

—XIANLI, YOSHIKO’S BROTHER

And then, suddenly, the bad times started and didn’t stop.

In August 1933 Yoshiko returned to Matsumoto after eight years away and, despite a fever, agreed to give a speech. Arriving at the packed hall, she discovered that the military police had issued a gag order.

“I complained to my father and to my brothers,” Yoshiko told her audience. “‘What’s wrong with letting me talk?’ I anguished over what to do. In any other prefecture, I wouldn’t care, but this happened upon my return to Shinshū, my second home, and so I am very upset.”

Excusing herself for a little while, she went to negotiate with the authorities and managed to get the order lifted. Once back at the podium, she began to tell her hometown listeners about what she had been doing. Her clothes proclaimed her sympathies, for she was wearing not a Japanese military uniform but a man’s black Chinese robe and cap.

“Think of me tonight as that wild child who left town on a work assignment and now has come back in rags to visit her second home for a little while.”

No wonder the police tried to keep her quiet, for Yoshiko went on to extol peace, Sino-Japanese amity, the essential unity of all people. This humane approach did not accord with the bellicosity the Japanese military was trying to stir up in the populace as the fighting in China proceeded.

Yoshiko in Chinese clothes Courtesy Hokari Kashio

“As commander I have ventured out into the hail of gunfire a number of times, and indeed I have sustained three bullet wounds. But when I think about it, I see that, friend or foe, we are all brothers.”

Yoshiko must have made the police even more nervous when she described the hopes of the people of Manchukuo. According to her, they considered the occupying Japanese incarnations of the Buddha and awaited blessings of compassion and mercy. The people of Manchuria had a long wait ahead of them.

In this speech, Yoshiko can again be seen grappling with new perceptions of her world, which had gone thoroughly awry. But she seems to lack the will or capacity to do anything more than express her alarm. Yoshiko has been criticized for not presenting new approaches or policies that would assist those in need of her help. Her focus on the restoration of the Qing dynasty was definitely not sufficient. “She had no ideals and no ideology,” writes Harada Tomohiko. “And virtually no sense of what it takes to live in the modern world.”

Her brother Xianli issued a harsher critique when he took the measure of Yoshiko’s achievements. No matter that he was hardly the one to talk about nobility of vision, his disdain is not easily forgotten: “Yoshiko had no ideals, and also she associated with many vulgar people. If she had been educated so as to construct an intellectual framework in her mind, she might have played some kind of role in history since she was smart, with sure instincts, and had outstanding natural abilities. But she was unfortunate in her family and was born with a peculiar sort of personality. So you can sum up her life by saying that she just went about meaninglessly, always carried away by whatever struck her fancy.”

Although the times called for focus, she could not bring clarity to her principles. To the end, her view of current events remained inchoate, shifting, a muddle, and a piece of solid belief in one area did not mean that anything firm was just beside. Frank about her growing confusion and disillusionment, her shock and shame, she was at least able to describe her moods to the public, who kept coming in to listen.

Yoshiko’s floundering state was confirmed several weeks later when she was back in the news. She had visited the resort town of Atami with some friends, including the dance instructor who was her new companion. When the inn’s owner refused to allow a group photograph out front, Yoshiko and her pals took offense. They stormed into the inn with their dirty shoes on, a grave breach of Japanese etiquette, and generally disturbed the peace. “Behaving in a rowdy fashion,” a newspaper reported, “Yoshiko used the cushion from the reception area to wipe off her dirty shoes. Things gradually got more out of hand and turned into a big commotion.” Eventually apologizing for their rudeness, Yoshiko and her friends made their getaway by car that night.

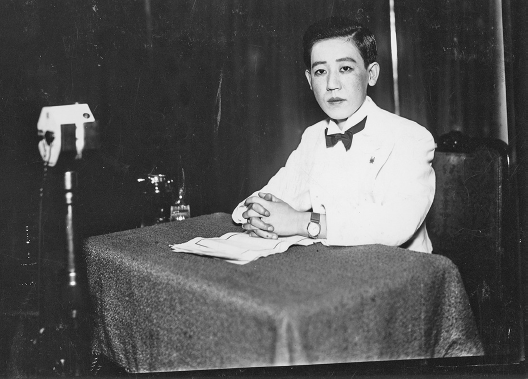

Yoshiko in radio studio, around 1933 © Bungeishunju

More than anything, it was her next boyfriend who made clear where she was heading, and the crash, long in coming, should have taken no one by surprise. Itō Hanni was a perfect companion for a woman willing to overlook matters of fraud and absurdity in exchange for media attention and money. Itō had taken the stock market by storm early in his career, explaining that certain investment strategies were guided by his personal astrologer. With a con man’s verve, he sold himself as the “genius of speculation” and persuaded investors to put money into his schemes, siphoning off quantities of funds for himself and becoming, intermittently, very rich.

Up, down, rolling in cash and then on the run, Itō had a literary side as well. He wrote books, songs, and at various times ran a newspaper and magazine. The power of words, his own in particular, intoxicated him, and Itō set out on lecture tours in Japan and China as his publicity proclaimed him a “messiah.” Huge crowds came to hear him expound upon his philosophy of “New Asianism.” Like Yoshiko, Itō depended upon a hodgepodge of shifting ideas to attract fans; in his case, the thoughts took much from Rudolf Steiner, who was a favorite of his astrologer’s. To his Japanese audiences, shaken by hard economic times and hostilities abroad, Itō forecast the triumph of Japan and the decline of the West.

Rescue all Japanese citizens from the wretched economic hardships of the past decades!

Japan has no connection to the economic hardships of the rest of the world. There is a way toward everlasting economic prosperity. Hanni has discovered this way. And he has discovered the real way that humans should live.

This is Hanni’s “New Asianism,” which will rescue men and women from debt, poverty, and the sufferings of illness. Both the British Empire, which possesses one-fifth of the world’s land and wealth, and the big United States, which holds two-thirds of the world’s gold, are agonizing over unemployment and economic depression. This is because their politics are bad. Even though they have money, Britain and the United States are suffering through economic depression.

Isn’t this proof that even without money, Japan can achieve economic prosperity?

Eventually Itō’s rock star status on the lecture circuit whipped him into such euphoria that he forgot about the police, who also came to listen. When he began to advocate revolution and other rousing concepts during a time of great political turbulence in 1935, he was arrested and charged with swindling.

But before Itō was jailed, Yoshiko joined his entourage, and the journalists agreed that this was an ideal couple. The two made the rounds of dance halls together, and Yoshiko attended Itō’s lectures, apparently won over by his teachings. For one public appearance she turned herself out in brash feminine clothes—a crimson Chinese outfit—and fended off reporters, who wondered whether a marriage was in the offing.

“You have returned to being a woman. Is that because marriage is in the cards? What about Mr. Hanni as a prospect?”

Yoshiko had a sassy response to this query, citing the stiff price of taking her on. “I’ll be happy to marry anyone who will have me, but for my expenses, I require more than ten thousand yen a month.”

The couple lived together in Tokyo, and an acquaintance remembers the bright-red bedcover and green rug, as well as the sign on the bedroom door, which proclaimed this “The Commander’s Room.”

With Itō’s money, Yoshiko returned to Matsumoto, where she hosted a seventieth birthday party for Naniwa, even though the tensions between father and daughter remained. Anyone who had followed their troubled connection could easily imagine the conflicts within Yoshiko as she organized the party; ever back and forth, she seemed to loathe and need her adoptive father.

There were about a hundred guests, with entertainment provided by masters of the traditional arts, who had been brought in from Tokyo along with two truckloads of party supplies. Yoshiko herself sang a ballad of congratulations to samisen accompaniment and again astounded those following her fashions. The impulses of a dutiful daughter may have been behind her birthday party for Naniwa, but she looked more like his geisha escort in her pricey, splashy kimono and elaborate Shimada wig.

Naniwa flanked by Renko and Yoshiko at his seventieth birthday party, 1935 Courtesy Hokari Kashio

Naniwa, resigned to his adopted daughter’s outlandishness, was heard to remark, “I never have the foggiest idea about what Yoshiko is doing.”

Twenty of Yoshiko’s former “soldiers” mingled among the guests, adding an odd touch to the gathering. “You only have to imagine the scene,” a reporter observed, “to realize how very amusing it was to see these weird-looking men prostrate themselves and pay their respects to this lovely Japanese woman.”

Later on, one of her men assured the journalist that this party was merely a break from Yoshiko’s serious endeavors. “The commander’s next moves are definitely worth keeping an eye on. Of course at this point we have not been told anything, but she is going to be living in a place called ‘The King’s Residence’ in Tianjin and is formulating some secret policies.”

Energized by public attention, Yoshiko is said to have piloted a plane bought with Itō’s money. Back in Tokyo, she was spotted at a sumo match in the company of prominent ultranationalists Tōyama Mitsuru and Iwata Ainosuke—he was the acquaintance from her youth who had supplied the gun for her failed suicide attempt. Since that time, Iwata had diversified his activities and, through his “patriotic” organization, become a dogged agitator for his radical ideas. Following his jailing for complicity in the assassination of a Foreign Ministry official, he’d gone on to play a part in the murder of a prime minister who’d compromised on a naval treaty with Western powers.

Yoshiko’s chumminess with such extremists was of course brought up at her trial in China, when she would claim that they were not political associates but almost family members whom she had known since her childhood in Naniwa’s home. While such assertions were in fact true, the Chinese court could assume that these men also found her useful to their agendas.

Despite the high-powered company, Yoshiko held her own in the sumo hall, no chance of being overlooked in her latest womanly concoction—“a pink Yūzen kimono with silver and gold embroidery on the long red sash, her hair in the high topknot Shimada style, and carrying a fan decorated with a bright-red peony.”

After Itō Hanni was arrested in 1935, there were sordid rumors about Yoshiko’s moneymaking efforts. Muramatsu Shōfū, who took credit for her fame, was appalled by her increasingly tempestuous behavior. He became more than appalled after she invited him over for a visit and then injected him with a potion she guaranteed would do wonders for his health. He fell violently ill and later suspected that she had tried to murder him with opium, because, in his view, he had refused her sexual advances in Shanghai. Convinced that friendship with Yoshiko was no boon to longevity, he avoided her from then on.

In addition to these unseemly antics, Yoshiko’s health worsened, and she sought cures as she shuttled back and forth between Japan and China. Among her ailments was a spinal inflammation, perhaps from an injury involving a plane propeller; she was increasingly dependent on various substances—what have been identified as painkillers, opium, and the like—consumed on a daily basis. At the same time, she became more distraught about Japanese brutality in China, and, probably liberated by the drugs, she was fearless about expressing her opinions in public.

When she was interviewed at a hot springs in Japan, where she was said to be recovering from a bullet wound, the reporter saw her inject herself in the leg with “glucose.” Afterward she talked politics, trying out new thoughts: “The establishment of the paradise of Manchukuo is still not easy. The Japanese must learn more about the land and the people of Manchukuo and deepen their understanding. Some surprising misunderstandings and rumors have started to circulate there.”

Around the same time, she met up with a Japanese businessman, who later became a prominent politician, and had discussions with him in Matsumoto restaurants. Decades later he remembered the courageous way she spoke out about the Japanese in China.

“At this rate, Japan’s policies in China are sure to fail. If they can’t put forward policies that encourage more understanding between Japanese and Chinese, then both countries will go to the dogs. When people like Doihara ride horseback on inspection tours through the towns, the Chinese have to get down on their knees before him. I’m telling you—making people do things like that will bring disaster to Japan also. There must be drastic changes in relations between Manchukuo and Japan.”

With tears in her eyes, she implored him, “For Japan’s sake too, please go to Manchukuo. I’ll tell Emperor Puyi that you’ll be there.”

All of her contradictions slam against each other at such times, and the impact resounds to this day. On the one hand she liked to woo the crowds by wearing silken, feminine Japanese kimonos, topped by fancy wigs. She sat in sports arenas with men linked to assassinations of public figures and dedicated to Japanese supremacy throughout Asia. She knew such people well, even calling them “Uncle.” On the other hand, she appeared in unadorned Chinese black for her speeches and railed against Japanese aggression in China that was instigated by those same intimates. She wept at the killing and the cruelty.

*

In March 1937, only months before the Japanese embarked on their full-scale war in China, which would lead to many millions of deaths, she gave another public lecture in Matsumoto before an overflow crowd. Yoshiko foresaw what was to come, and again in her black Chinese cap and robe, she took up her role as spokesperson for China, appealing for mercy beforehand.

Luster and strength diminished, Yoshiko had to be helped to the podium. One observer had no doubt that an opium addiction was behind her sickly appearance, which added impact to a gloomy message.

Yoshiko came to the point straightaway, her embitterment on full display: “All of you who have come here tonight have perhaps been drawn by an interest in me and some measure of kindness as well. If only the Japanese in China bestowed a smidgen of that kindness on our Chinese brothers and sisters, how grateful they would be!”

The fact of the matter is that many of the Japanese in China and in Manchuria have crossed the waters to make money hand over fist. I’m telling the truth and not exaggerating when I say that they’re only a bunch of losers no one would associate with in Japan, the kind of people who can’t hold down a job long enough to feed themselves. … The Japanese, who should become the leaders of Asia, go over there and all of a sudden make a quick change into un-Japanese Japanese. They bully our Chinese brothers and sisters, make them suffer, and strike terror into the hearts of the Chinese. They are hated. Tell me, is this acceptable behavior? …

Japanese from the Foreign Ministry, the military, the privileged, and the capitalists talk about Sino-Japanese friendship every time they open their mouths. But the Sino-Japanese friendship they’re talking about is only a Sino-Japanese friendship that profits the Japanese.

This amounted to a blatant denunciation of Japan and would not have been tolerated ordinarily, but Yoshiko, hometown celebrity and nationwide heroine, was not so easily hustled away. At one point she told the crowd that Japanese diplomats in China were utterly incompetent, like doctors who treat a patient with lung disease by administering stomach medicine. Her agitated voice rose when she reminded the crowd of her basic belief in the humanity of all people. With such thoughts in mind, she said, she had led her troops forward only in the cause of peace.

To confirm the authorities’ fears, the reporter covering the speech was moved by her words and saw reason to reflect upon her message. “She spoke directly and pointed out the flaws of the Japanese,” the journalist wrote. “She offered many suggestions and was truly an ‘Eastern Joan of Arc.’” Deep thinking about Japan’s China policies was of course just what the government did not want to encourage. Nor did it require a speaker, ailing and tearful, who had the power to move a large audience.

“As you can see,” Yoshiko said in a faint voice, “I also have been wounded and am now an invalid who can perform no useful service. But the least I can do is erect a stone memorial for our many dead brothers and sisters and bring solace to their souls. At the same time I will pray for eternal peace in Manchuria and Mongolia. That is absolutely all I can do. Please, I beg of you all, help to make this fervent wish come true.”