Her songs came to express the very sadness of those dark days.

—SATŌ TADAO

“She smiled, her face strikingly white, oval-shaped, and showing obvious refinement,” wrote Yamaguchi Yoshiko about the first time she saw Kawashima Yoshiko. It was 1937 in China, just when the Sino-Japanese War broke out, and Kawashima Yoshiko had once more changed her profession: she now ran a Chinese restaurant in Tianjin. “She was not tall but had a figure that went well with her size,” Yamaguchi continues in her autobiography. “Wearing a man’s black Chinese robe, she had the kind of beauty you see in a charming male actor who specializes in female roles.” So began a friendship that has been the subject of much analysis, for the two women would seem to have had much in common. The scrutiny has been unflagging, not only because of their common given name but also because of the similar perils they faced—one coming out alive and going on to flourish. The other not as fortunate.

“The two Yoshikos,” as they have been called so often, were actually rather far apart in age, with Kawashima Yoshiko older by thirteen years. She took note of her seniority immediately that day they met in her restaurant.

“When I was little,” Kawashima said to Yamaguchi, “people used to call me ‘Yoko-chan.’ So I’ll call you ‘Yoko-chan,’ and you call me ‘Older Brother.’”

Yamaguchi calculates that she herself was about seventeen at the time, and Kawashima over thirty, though she looked much younger. Yamaguchi was wary about this new acquaintance, and a reader of her memoir often gets the sense that she was not one to throw herself into a new connection without carefully evaluating what was on offer. And, certainly, Kawashima gave even those less cautious cause for worry.

Yamaguchi Yoshiko was born to Japanese parents in China in 1920 and as of 1937 had not yet set foot in Japan. That was why she could not immediately decide whether or not the man’s black Chinese robe that Kawashima had on was some kind of cutting-edge Japanese fashion. “In China,” Yamaguchi observes, “there are male actors who take female roles in opera, just like Japanese Kabuki, but there’s no custom of women taking male roles like Japan’s Takarazuka drama troupe. … So I didn’t understand what it meant for a woman to dress like a man. The only thing I understood was that this was a strange kind of beauty, her masculine charm drawing people in. I felt that I was looking at a living doll.”

Although still a student on vacation when she met Kawashima in the restaurant, Yamaguchi had already absorbed complex elements into her life, and these would multiply as conflicts between China and Japan intensified. While everything about Yamaguchi was consistently female, she could match Kawashima when it came to clashing loyalties and beliefs. The commentators like to equate her mixed-up background with Kawashima’s in other ways too, but they leave out deep psychological distress, which beset Kawashima frequently, while Yamaguchi, adept at adjustment to a churning landscape, seems to have been less vulnerable. Yamaguchi presents on the whole a hardier case, less likely to be shattered by anything that came her way, and certainly she was, over the years, pelted from many directions.

Yamaguchi’s father, a sinophile since his youth, taught Chinese to Japanese employees of the South Manchurian Railway. According to Yamaguchi, he was enraptured by Chinese culture from the start and carried on with curiosity and wonder, sometimes sounding, in her sweetened-up recollections, like that most winning of characters—an imperialist gone abjectly native. “My father felt we are the younger brother nation, China is the older brother. He would say, ‘You can do nothing to change China. China is so big, so deep. It has such a long history.’ Or, ‘What is the sense of taking one drop of the Isuzu River [a sacred river in Japan] and putting it in the Yalu River [in China]?’”

Yamaguchi’s father insisted that she learn to speak Chinese and personally supervised her study of the language. She gives credit to her musical ear for her mastery of Chinese, which she soon spoke fluently. Her health too played a part in her destiny, since she contracted tuberculosis as a young girl and took singing lessons to strengthen her lungs.

When Yamaguchi was thirteen, she made her public debut at a recital organized by her singing teacher. In one of those miracles abounding in memoirs, she tells of how a Japanese representative from a Manchukuo radio station was in the audience. He turned up again at her next singing lesson, bringing along his fateful offer. In order to attract Chinese listeners, the radio station was developing a new program that would feature songs from Manchuria. They had originally sought a Chinese woman singer who spoke both Chinese and Japanese, but in the end they could not find any Chinese who met their qualifications.

Giving up on the real thing, her Japanese sponsor decided to pass this young and lovely Japanese singer off as a Chinese, sure that she could sing about Manchu fishermen with all the conviction and linguistic proficiency of a native speaker. Yamaguchi was not being recruited to become an ordinary singing sensation, her photo to hang in every home in Manchukuo just to boost her career; rather, her songs would boost those old standbys, “Japanese-Manchu Brotherhood” and “Harmony of the Five Races.”

From that time forward Yamaguchi performed as a Chinese, known as the singing star Li Xianglan, whose remarkable voice and popularity would eventually storm across national barriers in a way that the politicians and military could never match. So complete was Yamaguchi’s immersion into her Chinese identity that she spent the rest of her long life trying to get herself and her public disentangled from the deception.

Yamaguchi went on to bigger things when she was hired by the Manchuria Film Association, headed by the murderer, opium boss, and zealous nationalist Amakasu Masahiko. The studio’s films also extolled the Japanese version of friendship with the Chinese, even going so far as to promote Chinese-Japanese romance. As the faux-Chinese actress Li Xianglan, Yamaguchi appeared on-screen as a Chinese woman who would not only be won over by the beneficence of the Japanese regime in China, she could even fall in love with a fine, high-principled Japanese man. In this way she proved that the Japanese, unlike those pillaging, imperialist Westerners, were lifting the Chinese up from their backwardness and, through patient instruction, bringing two ancient nations together, sampan and cherry blossoms commingled. Enchantment relied not only on Yamaguchi’s voice but also on her beauty, which let loose a magic not easily exorcised.

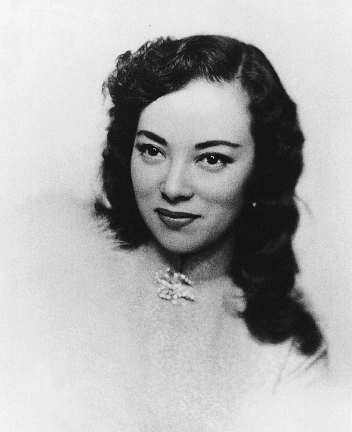

Yamaguchi Yoshiko Courtesy Yamaguchi Yoshiko

With a haunting voice and perfection in a cheongsam, Yamaguchi made her transformation look easy. Who would not want to be persuaded by an exquisite, supposedly Chinese woman, just married to a Japanese man and still in her wedding dress when she sang about evenings in Shanghai:

China nights—oh China nights

Lights from the harbor in the purple night

The junk coming upstream—a ship of dreams

Ah, I cannot forget the sound of Chinese strings

China nights, nights of dreams

*

But fame was still years away when Yamaguchi took a break from school and arrived for a meal at Kawashima Yoshiko’s restaurant in Tianjin. In accounts of their meeting that day and those to come, it is easy to see the pathos in Kawashima’s condition: the young Yamaguchi had film star glamour ahead of her while Kawashima’s glory days had come to an end. She was finished and seemed to know it.

Either Kawashima’s old lover and mentor Tada Hayao or a Chinese warlord was said to have been behind the establishment of the Tianjin restaurant. Preoccupied with management of a war, Tada hoped to keep Kawashima busy and far from where her capricious behavior and criticisms could cause trouble. The building that once housed the restaurant still stands in a seedy, neglected neighborhood, in Tianjin’s former Japanese concession. Ramshackle on the outside and evincing a decay that promises more of the same inside, the structure has not undergone the restoration that has improved other old buildings in the city. Still, the restaurant’s former cachet can be imagined, despite the grime and the shattered windows of the curved, second floor balcony. Elderly Chinese now congregate below that balcony where Kawashima’s customers used to look down onto the street as they dug into their Genghis Khan hot pot. The restaurant also had a less formal section that gained popularity around Tianjin since patrons could eat there standing up.

As an expression of gratitude for their services to Manchuria, Kawashima served Japanese soldiers tea and cake. “Those doing the serving,” Kawashima wrote, putting a brave front on things, “had rushed about on the Manchurian plains and fought at the front with the Japanese and Manchukuo troops during the pacification campaign at Rehe. They were heroes of the national army and so they had a good understanding of the hearts and minds of the Japanese army heroes. There was always a pleasant atmosphere in the restaurant and a great sense of military solidarity.”

That day when the canny young Yamaguchi Yoshiko walked in and had a look around the restaurant, she did not take long to comprehend Kawashima’s plight. At first Yamaguchi was eager to accept the many invitations from Kawashima that came next, attracted by the hedonism of her new friend’s social life, which provided a change from the dull routines of school. In her autobiography, written years later, Yamaguchi still captures the cruel accuracy of youth taking measure of a spent and ruined elder. “Kawashima Yoshiko gave me the opportunity to feel liberated from my family, school, and the monitoring of my activities,” Yamaguchi writes. “But I could also sense the sinister decadence and desperation around her. She wore her male military uniform only when she attended parties or ceremonies in her role as Commander Jin Bihui. Otherwise she wore her man’s black satin Chinese robe and cap. She always looked slightly flushed. She had a sickly pallor on her face, arms, and skin, so she put on light makeup and lipstick and made her eyebrows a little darker. She was always accompanied by a group of fifteen or sixteen women who were like her bodyguards. … Of course Kawashima was the queen of the group. No, she was always in man’s clothes, and so maybe she should be called the ‘prince.’”

Yamaguchi describes Kawashima’s daily life, which began when she woke up in the afternoon. “In Kawashima’s life, night and day were the exact opposite of what they were for an ordinary person.” Coming alive at night, Kawashima ate late with her entourage and then headed out to the dance halls and mahjong parlors, or any other distraction that suited her fancy.

Fascinated at first, Yamaguchi took it all in, but soon wearied of the pace and the company. “I gradually realized that Kawashima’s life as Commander Jin Bihui was over, and she had become utterly dissipated. The curiosity she had inspired as ‘Mata Hari of the East’ and those glory days when she had been praised to the skies as ‘Joan of Arc of the East’—all that was gone. The Japanese army, the Manchukuo army, and the right-wing China rōnin would have nothing to do with her anymore.” As Yamaguchi makes these assessments, her mental calculations are swift, and it is no surprise that Kawashima comes up short. Yamaguchi was soon heeding warnings that she distance herself from Kawashima and return to Beijing.

But this was only the first chapter of a connection that could not be severed so easily and is still invoked to contrast the fates of two women unable to figure out which country was their own. The China-born Manchu princess Kawashima Yoshiko who was brought up in Japan was caught in a similar muddle about where she belonged as Yamaguchi Yoshiko, the China-born Japanese woman brought up in China. They recognized in each other a bewildering patch of fog in the mind where others had the clearest skies. As they both discovered, this blur could affect confidence and judgment. By the time they met, Kawashima was merely seeking solace from a fellow sufferer, but Yamaguchi, just starting out, was keen to learn about the pitfalls ahead.

By the time Yamaguchi next saw her counterpart in Beijing, she had taken in enough information and had no interest in acquiring more. Crouching down in her seat in a movie theater, she succeeded in avoiding Kawashima, who arrived in her male attire with two soldiers. On Kawashima’s shoulder was a pet monkey. Fortunately for Yamaguchi, Kawashima did not have a lot of time to scan the audience for familiar faces since she stormed out at intermission, military escort and monkey in tow, loudly proclaiming that she was bored.

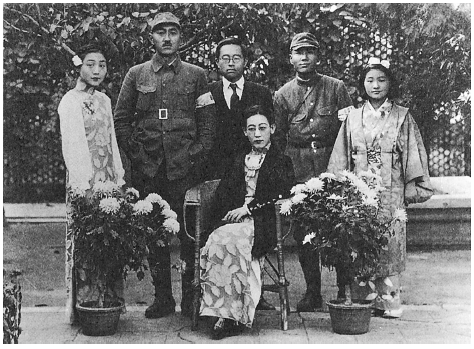

Yoshiko (seated) at her Tianjin restaurant, around 1937. Chizuko is standing at the left. Courtesy Hokari Kashio

Yamaguchi was not fooled by the display of bravado. “Later I found out that the two men with her were not part of her army but her household help, whom she had outfitted in uniforms and brought along with her.”

Yet Yamaguchi kept being drawn in, unable to resist the lure of this shade of her being, who was drug-addled and needy, confused and undone. Next time, as Yamaguchi walked down the street in Beijing, she was spotted by Kawashima, who was riding around in a Ford with the monkey on her shoulder; Yamaguchi did not refuse the dinner invitation. “A fondness for Kawashima Yoshiko welled up from somewhere inside me and so I got into the car.” Though reassured by the respectable appearance of Kawashima’s residence, which came complete with a guard at the gate, Yamaguchi was nonplussed by other aspects of the evening.

“I’ll never forget that strange scene. In the middle of the meal, Kawashima Yoshiko suddenly raised the hem of her robe just like that, exposing her thigh. Next she took a syringe out of a drawer at the side and deftly gave herself a shot. It was a white liquid. … She had a brother who was an opium addict and so there were rumors that she did not only use opium but also injected herself with other drugs. I also heard that it was a painkiller for her traumatic spondylitis. And then there’s the statement from her youngest sister, who said that she only injected herself with morphine.”

Yamaguchi does not mention that Kawashima’s career as a restaurateur came to an end when she got caught in the middle of a friend’s murder. The victim, sister of the Manchu warlord Su Bingwen, had become intimate with a member of the anti-Japanese resistance forces. When the relationship ended, the resistance feared that the woman would spill their secrets, and so they decided to kill her. She had already been attacked once but survived and was near death in a hospital when several attackers broke into the room to finish her off.

Kawashima, who happened to be at her friend’s bedside that night in late 1938, tells of her own matchless bravery and reflexes.

It was about eleven o’clock at night, and Mrs. Wang was holding my hand as she dozed off. …

Then three Chinese men stormed into the room with axes in their hands. I only had time to shout out in surprise, when those thugs bashed Mrs. Wang’s forehead with their weapon. Blood flowed onto her white pillow.

“What are you doing?” I yelled, rushing over to the man who was attacking her. As I fought with the assailant, trying to get the axe out of his hand, I was slashed deeply on a finger of my left hand. Now look what’s happened, I thought to myself as I fought with all my might to topple that thug. After that another attacker came over and hit me on my forehead.

Instinctively I let out a cry of shock, and as I recoiled, the second attacker saw his chance and assaulted me two or three times with his axe. Under attack front and back I continued to fight when yet another man assaulted Mrs. Wang with the death blow and fled, followed by the other two.

Mrs. Wang died, but Kawashima Yoshiko, though seriously wounded, survived after more than two months in the hospital. The newspapers erroneously reported that she had perished, and so she had the opportunity to read her own obituary. “The ancients proclaim that ‘only when a person is carried off in a coffin can you judge whether he was good or bad,’ meaning that a true evaluation of someone can’t be written until the person’s dead. In my case the newspaper and magazines attempted to size up the worth of my life and printed the obituaries even before my coffin had been readied. … They called me strange, flashy, romantic, adventurous, always after the bizarre.”

While she was in the hospital, her restaurant was shut down for nonpayment of rent.