I wonder what Yamaga-san and Kawashima-san’s lives would have been like if there had been no war and if they had lived in different times? The word “fate” is always on my mind whenever I think about this.

—YAMAGUCHI YOSHIKO

Kawashima Yoshiko next started stealing her old boyfriend’s clothes. This comes straight from Yamaguchi Yoshiko, who disapproved.

Yamaga Tōru, Kawashima Yoshiko’s first love, reenters the story in China around the time that she was managing her restaurant in Tianjin. Since Yamaga was last seen, he has adapted to changing times and resurfaces as a kind of cultural plotter for Japan’s Special Service Agency. Yamaga seems an unlikely member of such an outfit since he had an intense attachment to China, an unhealthy quality in a spy from the occupying army. He loved Chinese culture, as well as Chinese women and opium, and these indulgences certainly detracted from his performance as a ruthless and tight-lipped undercover agent.

Another person plagued by fluid allegiances, Yamaga was responsible for collecting information from the Chinese artistic world; this was an assignment suited to his particular skills. His spoken Chinese was excellent, and his acceptance into arty social circles was facilitated by his passion for Chinese actresses, who reciprocated the admiration. He knew the best out-of-the-way places to eat, like the restaurant that served only the thinnest and most tender slices of lamb. It is clear that Yamaga lived out the classic story of cross-cultural confusion—he had gone to China with the Japanese army, aiming to conquer and rule. In the end China affected his love life, his dining preferences, his loyalty. “The Chinese people seem to go along with what the Japanese tell them,” he once said, “but none of them believe what the Japanese military says. The Japanese have no idea how much the Chinese hate the arrogant Japanese. I’m sick of them too.”

There is a photograph of Yamaga as he was in those days, standing in front of a Chinese house with a curved roof and lattice windows. Wearing a Chinese robe and holding a fan, Yamaga does not look like a Japanese army officer after the rewards of a conventional career. Though he could claim that this Chinese attire was necessary for his official duties, he does not display the discomfort of a man walking around town in disguise. Rather, he seems to be trying to disguise ebullience, allowing only a faint smile on his round face.

Yamaguchi Yoshiko, who had known Yamaga since her school days, reports that Kawashima Yoshiko and Yamaga resumed their love affair when they found themselves in China at the same time. “I found out much later,” Yamaguchi writes, “that Kawashima considered Yamaga her first love. … The two of them met again in Beijing and became lovers. I sometimes wondered about their relationship. They were joined together by heart-wrenching feelings that sometimes came out as hate. They had to pursue their love against the background of those times, and both met violent ends.”

This description is tantalizing, inviting speculation about how and when these former intimates were reunited, but no hard evidence exists about their rendezvous. What we do know is that Kawashima Yoshiko had seen more of the unruly outside world than would have been predicted of the sequestered young woman who had once hung around Yamaga’s room in the Matsumoto bathhouse. Over time, they had come to share certain qualities, for Yamaga had also acquired risky habits, as well as subversive opinions about Sino-Japanese relations.

Yamaga did not abandon his other women for Yoshiko, and she could not abide his unfaithfulness. She became so enraged that she started swiping his belongings, entering his home when he was away. “I never knew what Yoshiko was going to do,” Yamaga confided to Yamaguchi. “Once I came back to my residence from headquarters and found the whole place empty. She’d apparently come in a car and removed everything.” Still, he preferred to avoid a row. “I can always buy new stuff. Thanks to her I bought myself this new suit and shoes.” Associating with Kawashima Yoshiko apparently invited many such incidents, and so Yamaga told Yamaguchi: “Better not to have anything to do with her. She’s poison, I tell you.”

The jealous Kawashima Yoshiko showed how poisonous she could be when she told the Japanese military police that Yamaga and Yamaguchi were having an affair, and moreover, that he was sharing military secrets with the Chinese. Having fits of jealousy over Yamaga’s relationships with other women was one thing, but making false accusations about traitorous activities to an organization known to torture and kill suspects on much less evidence was quite another. The police did not take her accusations seriously, but such condemnations of Yamaga surely made an impression on military officials, who acted on them later.

Not only had Kawashima mistakenly decided that Yamaga and Yamaguchi were romantically involved, she was jealous too of Yamaguchi’s success and liked to claim credit for this good fortune. “When she was a schoolgirl,” Kawashima complained about Yamaguchi, “I looked after her and really treated her well, but even so she’s betrayed me. I bought her a piano and even had a house built for her. Now that she’s become a star, she won’t give me the time of day. I’m the one who asked Yamaga to get her hired by the Manchuria Film Association. Because of that she became an actress. She’s just an ingrate.”

Yamaga had more reason to regret his connection to Kawashima Yoshiko when he joined the queue of military men ordered to assassinate her. Apparently Japanese officials were having a hard time finding someone to carry out this assignment. In the end, Yamaga managed to remove himself from consideration for this job, a refusal that could not have been easy.

“She wrote letters critical of the Japanese military’s operations in China,” Yamaga said, “and sent them to [Prime Minister] Tōjō Hideki, [Foreign Minister] Matsuoka Yōsuke, [ultranationalist leader] Tōyama Mitsuru, members of Japan’s political world, and top officials in the military. She called for a peace plan with Chiang Kai-shek. In addition to this, she was extremely critical of Lieutenant General Tada. … And she also caused me a lot of trouble. But when they told me to get rid of her, I couldn’t get myself to do it. After all, I had known her for a long time, and she was a Qing princess as well as a relative of the emperor of Manchukuo.”

In 1943 Yamaga was summoned back to Japan, where he was arrested. Some said that Kawashima was to blame, but others accused one of his discarded Chinese actresses of fingering him as a double agent. Found guilty of charges that included disclosing Japanese state secrets and drug use, Yamaga was sentenced to ten years in a military jail.

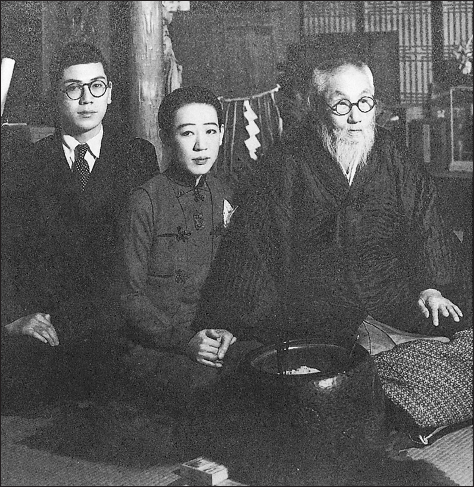

Yoshiko clasping the hand of Tōyama Mitsuru. To the left is her assistant, Ogata Hachirō, around 1943 Courtesy Hokari Kashio

“Yamaga certainly had traits that were not suitable in a military man,” Yamaguchi writes. “And maybe there was something that justified the guilty verdict at the military court. But I also knew how Yamaga suffered. … He had many deep relationships with the Chinese and felt that he knew every aspect of the Chinese people’s feelings like the palm of his hand. But as an army officer in charge of ‘Yamaga’s agency,’ what exactly did he feel about his work against the Chinese? He seemed to be suffering as he asked himself such questions.”

Yamaguchi did not see Yamaga again until he appeared at her Tokyo doorstep in 1949, after the war was over. He told her that he had escaped from prison during a bombing raid but had kept himself out of sight, fearing the he would be charged with war crimes. He was in debt, and although she could not lend him the sum he requested, Yamaguchi did agree to take care of Yamaga’s daughter. Soon after, Yamaguchi learned that Yamaga had committed suicide with a female companion in a mountain hut; his corpse had already been mutilated by dogs by the time it was discovered two months after his death.

*

Yamaguchi’s last encounter with Kawashima Yoshiko was just as grim, beginning in a Fukuoka hotel around 1940. Yamaguchi was by then a cinema idol in China and Japan, while Yoshiko was idling away her days far from the center of the action—just where military officials wanted her after they failed to get her murdered. The meeting of these two acquaintances did not begin well, for Yoshiko chose to lift up her robe in the hotel lobby, to show Yamaguchi the scars and fresh needle marks on her thigh.

“This is how I’ve suffered,” Yoshiko declared. “I’ve gone through hell thanks to my fighting for the Japanese army. These scars prove it.”

Yamaguchi did not warm to this kind of intense personal chat, and her displeasure drives the sentences that describe how she excused herself and retired to her room. A persistent Kawashima, who had reserved herself a room in the same hotel, came calling later on. She explained that she had come to town to take care of her adoptive mother, who was recuperating from some mental problems. “She didn’t know that I was aware of the truth,” Yamaguchi writes, “that in Beijing, orders had been issued expelling her from China, and so she was confined to Unzen.”

Struggling for equality in their exchange, Kawashima asked Yamaguchi to star in a film to be made about her life. When Yamaguchi, who had not heard anything about such a project, did not commit herself, Kawashima came up with another, grander suggestion. “I am planning a big national enterprise that will endure in the years to come. Kawashima Yoshiko will join hands with Chiang Kai-shek. I have formed a new political group with Sasakawa Ryōichi. … Please join us.”

Yamaguchi begged off, citing her busy schedule.

Yamaguchi was able to escape to a meeting, but she had not heard the last of Kawashima Yoshiko, who crept into her room late that night and deposited a thirty-page message by her pillow. Kawashima described her despair in purple ink, her rough written Japanese mimicking her spoken style.

It was wonderful to meet you after a long time. I don’t know what will happen to me after this. Maybe this is the last time we will meet. …

As I look back, I wonder about my life. I get a strong feeling that it’s all amounted to nothing. When much is made of you in the world, you are truly a flower. But during that time there are also people who come to you in reckless throngs, hoping to make use of you.

You shouldn’t let yourself get dragged along by such people. You should stick to your beliefs. This is the best time for you to speak up about exactly what you want for yourself. You do what you truly want.

Here before you is a good example of a person who was used by others and then thrown away like garbage. Have a good look at me. I offer this warning to you based on my own experience.

Now I feel myself in a wide field staring out at the setting sun. I am lonely. I wonder where I should walk all by myself. …

You and I were born in different countries, but we have much in common, even our names. I’ve always worried about you.