QUESTION: State your, name, age, and address.

ANSWER: I am Jin Bihui, thirty-two years old, from Beijing. My address is 34 Dongsi Jiutiao.

—FROM THE TRIAL OF KAWASHIMA YOSHIKO

According to a trial record, Yoshiko was arrested by the Nationalists on October 11, 1945, almost two months after the Japanese surrender.

“Is Jin Bihui here?” the police asked upon barging into her Beijing home. When Ogata said that she was sleeping off an illness, they went to get her.

“I was taking a nap at about one in the afternoon,” Yoshiko later wrote, “when a man suddenly came into my bedroom and jumped on me. I woke up with a start and found that he was a forty-year-old man with a round face, wearing a white shirt and black trousers. He looked like a laborer or a spy. He let out with a roar, pulled me out of my blanket, covered my head with a tablecloth, and forced me to walk on my bare feet. This was despite my repeated pleas to let me change my clothes and put on shoes since I was sick.”

Yoshiko was brought out in her blue pajamas, but as Ogata hurried to find something to put over her, the police thought he was going for a weapon and pointed their revolvers his way. Both Ogata and Yoshiko were taken to a waiting car, their faces covered and hands tied behind their backs. Ogata says that Yoshiko showed no sign of surprise as they drove off, and he always remembered the droll expression that he had glimpsed on her face. Even when the interrogations began, she made a point of mocking her questioners by ordering them to light her cigarettes.

“Ogata is a secretary in name only,” this former Qing princess haughtily informed her captors. “He is actually my loyal servant. Arresting a good person like that is a violation of human rights. Release him immediately.”

Yoshiko’s prison cell was primitive, and treatment by her jailers, harsh; a jeering reporter took pleasure in noting that these quarters were “completely different from her previous luxurious, extravagant way of life.” Eventually she tried to spruce up the décor by hanging up a photo of Yamaguchi Yoshiko, a reminder of another, happier time. Food would remain a problem until the end since she found the prison fare inedible. But her possessions had been confiscated upon her arrest, and so she had difficulty paying for meals brought in from outside restaurants. “Please help me,” she begged reporters.

In a country exhausted by wars and the struggle to survive, the trials of traitors provided diversion from the calamities of daily life. As the accused were rounded up, there was no consistency about who would be brought to trial and who would be allowed to remain free. While laws were cited in the trials, punishment was random, and, no matter how heinous wartime activities may have been, good contacts in Chiang’s regime could mean better treatment. Even Japanese army officers, who had laid waste to China since 1931, were able to get off given the right connections. Okamura Yasuji, commander in chief of Japanese forces at the time of Japan’s defeat, had instituted the brutal policy of “kill all, burn all, loot all,” which is said to have killed two million Chinese. Once the Japanese surrendered, Chiang took Okamura on as his military adviser and made sure that he was not prosecuted for war crimes by the Allies.

If the Nationalist government sought theatrical tribunals to divert the public’s attention from a failing economy and the uncertainty of China’s future, the trials of people like Ding Mocun served well in stirring up a lust for blood. He had been responsible for the torture of prisoners in that “palace of horrors,” his much-feared headquarters at 76 Jessfield Road in Shanghai. Ding had gained such a reputation for cruelty in the collaborationist regime of Wang Jingwei that a newspaper labeled him Wang’s Himmler. It is no surprise that the courtroom was packed when the five-foot, one-inch “Little Devil Ding” appeared in court.

As in all matters involving publicity, Yoshiko could compete with anyone, even the most despised defendants. The Nationalists continued to demonize her as a member of the reactionary Qing imperial family, a woman who had dedicated her life to bringing back her family’s oppressive regime and overturning the wonders of the Nationalist revolution. In addition, her close association with Japan made it easy to pile on accusations about her treachery. Then there were her love affairs, her hair, her mannish clothing, all making for grand titillation. “With her assistance,” read one rabble-rousing newspaper article,

some areas in Northeast China were occupied, and she agreed to give up Chinese lands to the Japanese. Everyone felt most gratified to see her in legal custody. No one apparently knows how many of her handsome male “concubines” lost their lives in her residence at 34 Dongsi Jiutiao. After making love with Yoshiko, those men became laborers in the production of heroin, eventually dying of exhaustion. This was the reason why millions of citizens crowded in to get a look at her on her way in or out of court, to see what kind of a “rare and beautiful woman” she was.

From the start, Yoshiko’s conviction was a foregone conclusion, but she incriminated herself beyond hope when she was bullied into confessing. She later told her lawyers that she had been lured into producing false accounts of her activities under much duress and after promises of better treatment.

“The court official told me, ‘Look, even if you don’t know anything, just write down what other Japanese have said or what the people from those fake puppet governments have said. Then the chief will be happy. He’ll be able to say that you helped the government and then he’ll send you back to Japan.’ I was happy and believed them. I agreed to give them what they wanted. I didn’t sleep the whole night thinking that if I went back to Japan, I wouldn’t leave out a thing in telling all about those military men who had treated me so badly.”

Seeking sensational revelations, Yoshiko’s interrogators were not satisfied with her initial efforts and made their displeasure clear.

The next day, having read what I had written, the court official’s gentle expression of the day before was gone.

“I don’t believe any of it,” he angrily told me. “How can you write such a thing? I received big orders from the chief and so I cannot pass this along to him. First of all, this won’t help you. We have treated you as an important person. If I show this document, which is full of empty words, to the chief, you’ll be considered completely uninteresting to us, a useless person, and we’ll give up on you. You’ll have to stay inside here forever. Write something, it doesn’t matter what. The chief has especially kind feelings for you and so has sent me all the way over here to talk to you. I don’t want to feel that I’ve been wasting my time. I would like to save you. You have to confess to as much as possible and show the chief that you are a very important person. Otherwise, there’s no way to get you released. You’ll be imprisoned here forever just like everyone else.”

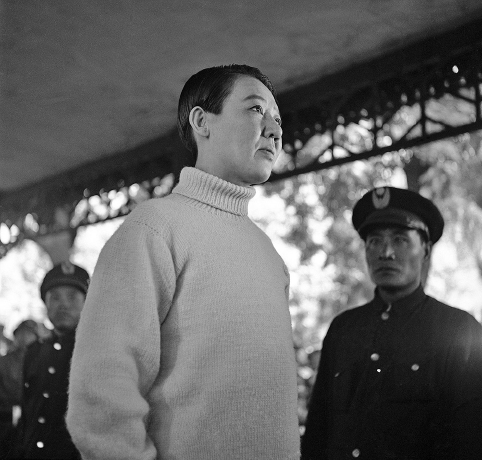

Yoshiko at her trial, October 1947 Associated Press

Yoshiko complained about being humiliated in jail, forced to kneel on the ground with a plate on her head, subjected to constant abuse, and fearful of rape and starvation. Such hardships made her amenable to a female official’s promises of food and clothing if only she submitted a report about her past deeds. “I thought that since I am a woman, she sympathized with my plight and so I told her, ‘I’ll just make up something to give to them.’ … I told her that I was in trouble and cried.”

Trying to please, Yoshiko let her mind wander and came up with the sort of thrilling vignettes she had so often fashioned for her public. Only this time she was on trial for her life, and boasting to Chinese officials about parachuting into Manchuria to help the occupying Japanese army or about her indispensable aid to a high-ranking Japanese officer was not the same as telling these same cooked-up stories to a reporter from a mass-market women’s magazine in Japan. She implicated herself in wartime activities that had been detrimental to China, even when she had played no role at all, but anyway she apologized for any harm done, explaining that it had turned out badly because she too had been double-crossed by the Japanese.

Hyperbole her medium, she rehashed one of her most publicized, but made-up, stunts—her supposed attempt to get the Manchu warlord Su Bingwen to cease his rebellion against Japanese control and also release his Japanese hostages. “I piloted the plane myself and went to Qiqihar,” she wrote.

Upon arriving there I sent a telegram to Commander Su. He replied that very day. Commander Su never answered the telegrams sent by the Japanese military headquarters, the provincial government, or the emperor. Strangely enough, Commander Su always replied to my telegrams. The Japanese newspapers published articles about this every single day. Before I knew it, I became well-known in the Japanese press as a person capable of doing anything. But after I rescued the Japanese held by Commander Su, the Japanese deceived me again. I was left completely alone there at the mercy of Commander Su. Once all the Japanese had been rescued, the Japanese army launched its all-out assault. I completely lost face with Commander Su and did not dare see him anymore. I just waited to be killed, but I did not die.

There is often a disjointed flavor to her confessions, reminding us that she was not only hungry and beset but also withdrawing from a drug addiction and could not keep her mind focused on the main points of her defense.

Interrogated repeatedly, her accounts expanding and tilting in different directions, Yoshiko did not seem to understand what she was up against and, disdainful of the authorities, believed that the charges of treason could not be corroborated by the facts. But, as it turned out, where the facts were lacking, the court would point to the evidence found in Muramatsu Shōfū’s novel The Beauty in Men’s Clothing as well as in Mizoguchi Kenji’s 1932 film The Dawn of the Founding of Manchuria and Mongolia, which also featured a fictionalized character modeled on Yoshiko. With incriminating proof provided by noted Japanese creative artists, the Chinese judges saw no reason to look further. Astonished that fiction would pass for evidence, Yoshiko ridiculed this legal approach: “They say that novels tell of outlandish events. You take that famous Journey to the West. Only Xuanzang is a real person. You’re not going to tell me that Monkey and Pigsy actually existed?”

Still, Yoshiko’s scattershot confessions, though wanting in coherence, do succeed in conveying the mixed-up but true emotions she had tried to organize throughout her life. It was already an old story, for she had repeated these sentiments time and again, but at this critical time also, she insisted that, as a Chinese, she hated the Japanese for mistreating the Chinese. “My father taught me to promote goodwill between China and Japan, but he didn’t say become the slave of the Japanese.” And remember, she told her interrogators, she herself had been mistreated by the Japanese. “I was sometimes so furious that I could have died. I am considered the daughter of Kawashima, but I also have Chinese siblings, sisters-in-law, and other family members. The Japanese ignored my opinions. They used me as they wanted. To this day I can’t get along with such people, and anyway they are cold to me. That is why I am always alone.”

Yet her attachment to China was complicated by her inadequate mastery of spoken Chinese (she insisted upon a translator during her trial), which made it difficult for her to form intimate bonds in her place of birth. “I couldn’t understand what was happening in China. I couldn’t speak Chinese very well. I didn’t have a clue about the names of important people in China nor about Chinese culture. How could I do intelligence work?” She did not feel a part of what was going on in her Chinese family, on the Chinese streets, in the Chinese newspapers, and so, in her telling, it was natural to drift toward the Japanese side. Communication was easier; also it was no secret that she liked certain Japanese individuals, even though they were committed to destroying China.

“I’ve worked as a secretary for Matsuoka Yōsuke. I’ve known him since I returned to China at age sixteen. He worked for the Japanese military and often complained to me about his great distress. There are some kindhearted people among the Japanese.”

*

The Associated Press correspondent in Beijing wrote a rare, measured account of the opening day of Kawashima Yoshiko’s trial on October 15, 1947, in an article headlined “Asia Mata Hari on Trial for Jap Espionage.” The AP reporter estimated the crowd in the hundreds, and described the site of the court proceedings as “held in the open in what resembled an improvised stockade. The once-glamorous woman drove up in a heavily-guarded automobile. Her hair was chopped close like a man’s.” But the crowd was raucous and unruly from the moment Yoshiko arrived in the warden’s black car.

More common was the excited tone of a Chinese report:

The flood of local citizens who did or did not have tickets surged through the iron gate. Like a flood from a broken levee, more and more citizens without tickets joined the flow and rushed into the square. People of different classes and professions mixed together along with crying babies and yelling mothers. All faces turned purple, bathed in sweat.

“Why did we bother to come?” some of them loudly complained.

The people who jostled into the square stopped to catch their breath. Those who couldn’t enter had to climb trees to watch the trial from a distance. Everyone seemed to enjoy joining the commotion. When they saw Jin Bihui enter the square, the crowd pressed toward her, surrounding her so she couldn’t move.

“The judges don’t know how to control the situation,” went the shout. “If there is no way for Jin Bihui to enter the square, what will they do?”

The hot-tofu vendor was asked to monitor one of the parking areas, where he had set up his cart, and he estimated that 120 bicycles had collected there in just a few hours. Stars from the Beijing opera mingled with the crowd, as did a man who had adopted Yoshiko’s pet monkey. “After she was arrested,” the monkey’s new owner told a reporter, “no one wanted to take care of him, so he was sent to my place. He is now living in a passageway in my house and eats steamed buns and rice with some vegetables every day. He is very well behaved and helps to look after my house and catch lice. He enjoys smoking, and sometimes he goes off for a while to meditate.”

As the trial commenced, the defense tried to present its case, despite the commotion stirred up by the spectators, including those hanging from the trees “like watermelons” to get a better look. The court was adjourned when a group of observers broke through the fence and poured into the open space where the proceedings were being held. “Since the judicial staff members were concerned about their personal safety, it was impossible to continue, and the head judge announced the suspension of the trial.” On the second day, the trial was moved inside the prison with a smaller group of observers present.

In this more private session, Yoshiko fared no better. She had been charged as a “traitor” (hanjian), a capital crime that specifically applied to a Chinese who had aided the enemy. In an argument crucial to her defense, her lawyers insisted that she was exempt from being considered a traitor since she was not a Chinese but a Japanese citizen, having been adopted by the Japanese Kawashima Naniwa when she was a child. As a foreigner in China, she should be tried as a war criminal, and if so charged, her lawyers believed that she would escape execution.

Yoshiko’s defense team also wanted to convince the court that she was actually about eight years younger than she actually was, making her too young to carry out the crimes cited by the prosecution. Consistently and fruitlessly, her lawyers objected to the quality of the court’s evidence—its reliance on false assumptions, fiction, and cinema.

Novels and movies describe fictional events. Just as in the folk songs sung by the blind, there have always been many examples of virtuous people being portrayed as crafty evildoers in novels and plays. Is it possible to take these as the truth? The sages of the holy books in fact sometimes write that it is better not to read books than to believe what is written in books. Using vague, made-up stories and rumors as the basis for a judgment in a trial, and, worse, a death sentence will not only confuse people but also seems to treat human life carelessly.

In one of her statements, Yoshiko denied everything and insisted upon the preposterousness of the charges. “My father is of Chinese blood. If China had been defeated, I also would have become a slave in a conquered nation. Why in hell would I help the Japanese defeat the Chinese? … I seek only peace in the world. Not only my adoptive father but also the father of the nation Sun Yat-sen emphasized this. How can anyone call me a traitor because of this? If I ever worked as a spy, then tell me, what was my number? Did anyone actually see me doing anything?”

When she had difficulties explaining away certain activities, she blamed her brother Jin Bidong, a prominent official in Manchukuo who could not defend himself since he had died in 1940. “I have many brothers and sisters, and people often get confused about who did what.”

In their rebuttals, the prosecution swept aside the points raised in Yoshiko’s defense:

The accused, Jin Bihui, also known as Kawashima Yoshiko, is the daughter of the late Prince Su of the Qing imperial family. She was adopted by Kawashima Naniwa and lived in Japan from her childhood. Influenced by her schooling in militarism, she likes to dress in male attire and admires the ways of chivalry and Bushido. Because of her relationship to Kawashima Naniwa, she came to know important military and political figures in Japan. Submissive to the whims of an enemy country, she allowed herself to be used by them. According to our evidence, after the September 18 Incident of 1931 [when Japan invaded Manchuria], she participated in traitorous acts against her native land in Shanghai, the Northeast, and other places. For these reasons, we believe that the guilt of the defendant is consistent with the Traitor Punishment Ordinances, Article 2, Paragraph 1, Subsection 1 of the Criminal Code.

Against this condemnation, Yoshiko could make only a feeble response: “I don’t understand why the prosecutor says such things about me. I became Kawashima Naniwa’s adopted daughter not because of my own wishes but because my father sent me there. I didn’t know I was a Chinese until I was sixteen. I was extremely sad at that time and hoped that conditions in my country, China, would improve with each passing day. … Do you really think that my conscience would allow me to help foreigners attack my native land?”

The prosecution’s case seemed particularly shaky when they brought in personal qualities that, they claimed, proved beyond a doubt that she had been involved in nefarious deeds:

The accused is a descendant of the Qing imperial family and has devoted herself to the restoration of the Qing dynasty. She has been brainwashed into supporting Japanese militarism since her youth. She is good at horseback riding, shooting, swimming, running, skating, dancing, driving cars, and piloting airplanes. Though over thirty years old, she is not married. In short, she has all the qualities required for espionage work.

Her lawyers naturally disdained such conclusions: “The prosecution concludes that the defendant is proficient at various languages and has certain skills, so she has all the prerequisites to be a spy. I would like to provide an example to rebut these ideas. In the old days in China, there was a popular story that said that a man who owns sex toys must have committed rape. I would like the judge to think of this story when making his decision.”

As scholar Dan Shao points out, Yoshiko’s lawyers emphasized her Manchu ancestry in their desperate bid to prove that she was not a traitor. Everything she had done—aiding the Japanese, supporting Emperor Puyi’s rule in Manchukuo—came from her attachment to her Manchu heritage and her wish to improve the Manchus’ lot. “I am Manchu, and people living in the interior of China are not able to acquire a proper understanding of us Manchus,” she had told reporters months before her trial.

Driven by such ideas, Yoshiko’s lawyers explained, her actions had caused conflict within the one vast Chinese family but did not rise to broad-based treason against the entire Chinese nation. She had, in short, merely been on the losing side in a civil war. “The indictment states,” her lawyers argued,

that the defendant, taking on the dreams of her father and following Kawashima’s teachings, dedicated herself to the restoration of the Qing dynasty. But such an intention amounts to nothing more than her involvement in internal strife and therefore does not merit convicting her of treason. And anyway, the defendant took no action that would have brought about the restoration of the Qing.

Less memorably, her lawyer sought to excuse her because of her unhappy childhood, which he decorated with various untruths. “Finally, we ask the court’s sympathy and compassion for the defendant. She was born in Japan; both her father and mother died when she was three years old. She was sixteen when she learned for the first time that she was Chinese. We must really sympathize with the plight of this girl, who lost her native country’s protection and then was deprived of her parents’ tender love.”

On October 22, 1947, Kawashima Yoshiko was sentenced to death, found guilty of aiding the enemy and betraying China. The verdict condemned her for such activities as becoming a dancer in Shanghai in order to gather information for the 1932 Japanese onslaught there; bringing the empress to Changchun, with the help of her brother Jin Bidong, to install her as the female ruler of Manchukuo; serving as adviser to Tada Hayao in building up the military in Manchukuo and other military plots; trying to get Su Bingwen to surrender; leading bandit troops to establish a puppet regime in Rehe with Puyi as head; plotting to bring Puyi to Beijing in order to revive the Qing dynasty and overthrow the Nationalist government—and so on.

The judgment was patchy, ranging from those deeds she may have undertaken, definitely did not undertake, confessed to undertaking but later denied. As proof of the cavalier approach to the facts, she was also found guilty of heading an organization backed by the Japanese military that had actually been headed by another Japanese woman. In a 2012 documentary, her sister Jin Moyu expressed the skepticism of many when she reviewed the accusations. “A spy needs to be very intelligent and well educated. Yoshiko was not up to that level. … She was extremely bold and often made daring remarks. She could get carried away. I knew that but I don’t know if she knew that too. I don’t think she had the qualifications to be a real spy.”

Most devastating to Yoshiko’s defense was the court’s determination that even if she had been adopted by Kawashima Naniwa and officially taken Japanese citizenship, she was still a Chinese citizen because her birth father was Chinese; she could therefore be labeled a traitor to China and executed. Her Chinese blood meant more than any document pointing to foreign citizenship.

Yoshiko herself realized that others had collaborated with the Japanese in ways more damaging to China and still survived, but she also realized that the public’s anger, stoked by damning media accounts, made her exoneration unlikely. “Apparently a newspaper here wrote that they should put me on show, charge admission to see me, and give the money to the poor.”