1 Introduction

Sexual assault is a unique crime in that most victims are female and most offenders are male. The gendered nature of sexual assault explains why the crime is characterised by delayed complaints, no eyewitnesses and little or no forensic evidence because the essence of the crime is about power and control.

As discussed in Chapter 1, the crime is also characterised by low reporting rates, high attrition rates and, compared to other crimes, low guilty plea rates and relatively low conviction rates. Because of these low conviction rates, the focus of this and the next chapter is on jury decision-making in order to understand the decision-making processes of disparate groups of laypeople when faced with allegations of sexual assault by a child or adult complainant. In other words, police and prosecutorial decisions to drop a case or charge a suspect are made in the shadow of the adversarial trial where only about one-third to one-half of sexual assault trials will result in a guilty verdict.

Jury decision-making in criminal trials has been the focus of considerable academic interest over the years, largely because the criminal justice system invites laypeople to be the triers-of-fact within a complicated legal process. Nonetheless, it is commonly believed that juries, as an integral part of the criminal justice system, get it ‘right’ most of the time (Bornstein & Greene, 2011) and that ‘“verdict, “correct result” and “justice” are co-terminous’ (Hill & Winkler, 2000: 401).

In countries, such as the UK, the USA and Australia, there is a history of hundreds of years of jury decision-making without, until the mid-twentieth century, any measure of the extent to which jury decision-making constitutes the best way to decide guilt or innocence in a criminal trial. Although jury trials have diminished in importance in some jurisdictions, jury trials are still the most common form of adjudication in Australia for indictable offences, although judge-only trials are available in certain circumstances.1

In the UK, the most serious criminal offences are tried in Crown Court where a jury will be the trier of fact unless a judge-only trial is held2 although the cases tried in the Crown Courts represent a minority of all criminal offences prosecuted. Nonetheless, jury trials are still relatively common in the prosecution of sex offences in the UK since Thomas (2010: 26–28) found that juries in England and Wales were more likely to return a verdict in relation to a sex offence than any other type of offence so that ‘the single largest proportion of jury verdicts are for sexual offences (31%)’, partly because defendants were more likely to plead not guilty to a sex offence compared to all other charges (except homicide and proceeds of criminal conduct).3

- i.

No ear- or eyewitnesses;

- ii.

A delayed complaint;

- iii.

No forensic evidence of the alleged sexual act, or the inability of forensic evidence to prove lack of consent;

- iv.

No confirmatory medical evidence of the sexual act;

- v.

The consumption of alcohol and/or drugs by the complainant and/or the defendant;

- vi.

Counter-intuitive responses by the victim during and after the sexual assault; and

- vii.

Word against word oral evidence.

a psychological analysis of the criminal justice system is needed to understand its apparent resistance to decades of attempts at reforming rape law, and to develop procedures that are not inhibitory to people reporting offences or authorities’ investigation and prosecution of them. In particular, an understanding of rape stereotypes and the attrition problem are needed if we are to restore faith in the criminal justice system.

To that end, this book canvases the impact of rape myths and misconceptions on jury decision-making, as well as providing a historical and theoretical analysis of the entrenched rape-supportive beliefs within the criminal justice system when it comes to the prosecution of sex offences. While jury decision-making is only one part of the problem associated with investigating and prosecuting sex offences, the question is whether the jury trial is the best mechanism for determining the guilt or innocence of defendants within the gendered structure of the criminal trial, particularly since juries are comprised of laypeople who bring a number of myths and misconceptions to the jury room about rape and the behaviour of sexual assault victims.

legal knowledge and training to hear evidence that has been carefully chosen … to make sense of sometimes conflicting facts, and to apply legal rules … in order to reach a verdict. (Blackwell & Seymour, 2014: 567)

This lack of juror expertise is particularly salient in light of research that suggests that juries exhibit a pro-acquittal bias or a leniency asymmetry effect as a result of deliberation and the ‘liberation effect’ (Kalven & Zeisel, 1966), as explained below.

- i.

jurors’ perceptions of guilt based on ‘commonsense’ or ‘life experience’;

- ii.

the cultural climate in which sex offences are prosecuted; and

- iii.

a literature review of the extent to which laypeople adhere to misconceptions and myths about women, children and sexual assault and the influence of these myths/misconceptions on outcomes in sexual assault trials.

2 Jury Behaviour: Understanding Sexual Assault Trials

In order to understand the difficulties with prosecuting sexual assault trials, it is important to understand jury decision-making, in particular the two phenomena that have been reported in the literature: the majority effect and the leniency asymmetry effect, since both help explain the tendency towards acquittals in sexual assault trials.

To begin, I turn back to the mid-1950s when the first studies on jury behaviour were conducted and the Chicago Jury Project was launched. In documenting the results of this landmark study, Kalven and Zeisel (1966) found that while judges and jurors agreed on a verdict in 78% of cases, overall, jurors were more lenient than judges, acquitting twice as often compared to what judges would have decided. In explaining this degree of judge–jury disagreement, Kalven and Zeisel (1966: 495) hypothesised that, in trials with ambiguous evidence (the typical situation in a sexual assault trial), juries are ‘liberated’ from trial constraints and rely on their commonsense assumptions and beliefs to resolve doubts about the evidence.

This hypothesis, known as the ‘liberation effect’, implies that ‘jury verdicts will be determined by the strength of the evidence … but susceptible to non-evidentiary influences when the evidence is “close”’ (Devine, Buddenbaum, Houp, Studebaker, & Stolle, 2009: 136). In a sexual assault trial, such extra-legal factors could include the race and ethnicity of the defendant and complainant, as well as rape myth acceptance (RMA) beliefs.

In a partial replication of Kalven and Zeisel’s study, Eisenberg et al. (2005) also found a high rate of judge–jury agreement (75%) and a similar pattern of disagreement in that ‘juries are much more likely to acquit when judges would convict than they are to convict when judges would acquit’ (Eisenberg et al., 2005: 173). In other words, juries have a higher conviction threshold than judges, something that Kalven and Zeisel (1966: 189) believed was due to juries ‘more stringent view of proof beyond a reasonable doubt’.

Judges’ willingness to convict exceeds 50 percent of cases even when jurors regard the evidence as largely favourable to the defense—“3” on [a] 1–7 scale. As the evidence favouring the prosecution moves from “4” to “5”, jurors willingness to convict soars to over 90 percent.

Eisenberg et al. (2005: 191) also found that ‘judges’ lower conviction threshold does not appear to be a function’ of either case or legal complexity. Nor did they find any association between juror characteristics, case characteristics and locality. Overall, there was ‘at least a 12 percent increase in probability of conviction’ with a judge as adjudicator, although evidence strength dominates case outcomes in that ‘stronger evidence of guilt is strongly associated with increased likelihood of conviction’ (Eisenberg et al., 2005: 196, 198). Some juror characteristics, such as gender and educational levels, were associated with outcomes in some localities, in that male jurors were more likely to convict while increased educational levels corresponded with a likelihood of acquittal. In fact, Eisenberg et al. (2005: 201) suggested that ‘education … also helps explain judge-jury disagreement’.

2.1 The Majority Effect

In addition to the higher conviction threshold of juries compared to judges, jury research has also revealed the existence of a ‘majority effect’ on jury decision-making. After conducting post-trial interviews, Kalven and Zeisel (1966) reported that the majority verdict of jurors prior to deliberation became the final verdict in 90% of 225 trials. This finding was supported by a later study which showed that the initial majority verdict of a jury ‘approaches 100% when two-thirds or more of the jury favors [that] particular verdict’ (Devine et al., 2004: 2070) for both actual jurors (Devine et al., 2004; Kalven & Zeisel, 1966; Sandys & Dillehay, 1995; Zeisel & Diamond, 1978) and mock jurors (Huang & Lin, 2014; MacCoun & Kerr, 1988).

This ‘majority effect’ has led to the view that deliberation has little impact on jury outcomes (Kalven & Zeisel, 1966; Devine, Buddenbaum, Houp, Stolle, & Studebaker, 2007; Salerno & Diamond, 2010) since it appears that the initial majority view (that is, the sum total of individual opinions) prevails throughout the deliberation process (Devine et al., 2004). In other words, it is believed that the real decision is made before deliberation begins (Kalven & Zeisel, 1966: 488) with some researchers ‘using individual opinions … as a surrogate for the group decisions of mock juries’ (Sandys & Dillehay, 1995: 176). Indeed, reversed verdicts, where the final verdict differs to that of the majority at the beginning of deliberation, are relatively rare (Devine et al., 2004; Tanford & Penrod, 1986).

In sexual assault trials, for example, the ability of some jurors during deliberation to counteract the impact of issues such as gender and RMA on individual opinions may be limited if a majority favours an acquittal before deliberation takes place. This is particularly important when considering the leniency asymmetry effect.

2.2 The Leniency Asymmetry Effect

The robust finding that deliberating jurors (both actual and mock) are prone to a majority effect contrasts with a leniency or asymmetric effect which predicts that juror factions favouring acquittal are more likely to prevail than those favouring conviction. The existence of a ‘leniency bias’ emerged from research which showed that juries with less than a two-thirds majority at the beginning of deliberation tended to acquit or produce hung verdicts (MacCoun and Kerr, 1988; Tanford & Penrod, 1986). Tanford and Penrod (1986) found a strong leniency effect in simulated jury studies involving jurors drawn from a jury pool in Wisconsin. Their study found that not only did majorities tend to prevail (with only 14 out of 100 juries reversing the original majority), evenly split juries tended to acquit, suggesting ‘a scheme in which majorities win, and evenly split juries tend towards acquittal’ (Tanford & Penrod, 1986: 331).

Meta-analyses by MacCoun and Kerr (1988) and Devine et al. (2001) show that the likelihood of a majority prevailing depends on its size and the verdict it favours. A majority that favours acquittal is more likely to prevail than an equivalent majority that favours conviction, an issue for sexual assault trials because of the extent of RMA in the general community (discussed under Part 5, below). This tendency towards acquittal is now referred to as the ‘leniency asymmetry effect’ and has been attributed to the high threshold represented by the criminal standard of proof (Kerr & MacCoun, 2012) and the fact that the burden of proof is on the prosecution. Deliberation itself may also increase the influence of group norms such as a bias in favour of acquittals (Davis, 1980) or the influence of RMA within a jury.

The question for this chapter is whether or not the leniency asymmetry effect is greater in sexual assault trials compared with other criminal trials, and, if so, what reforms would be needed to minimise this effect. Because of the typical lack of corroborating evidence in a sexual assault trial, it is likely that jurors will fill in the gaps in evidence by relying on their biases and misconceptions in assessing the credibility of the complainant and defendant and in reaching a verdict. Before dealing with this question in more detail, we need to know more about the leniency asymmetry effect.

In a meta-analysis of 11 studies, MacCoun and Kerr (1988) found that pro-conviction majorities in simulated criminal jury trials prevailed only 67% of the time, compared to pro-acquittal majorities which prevailed 94% of the time. Juries that were evenly divided at the beginning ended up acquitting 81% of the time. These results suggest that juries will exhibit a leniency asymmetry when at least a two-thirds majority does not exist at the beginning of deliberation, resulting in a final verdict that favours the defendant (see also MacCoun, 1984; Tanford & Penrod, 1986).

The leniency asymmetry effect manifests in juries with evenly split, or weak majority pre-deliberation factions and has been reported in simulated jury studies (Huang & Lin, 2014; MacCoun & Kerr, 1988; Park, Kim, Lee, & Seo, 2005) but has not been reported in studies involving actual jurors (Devine et al., 2004; Hannaford-Agor, Hans, Mott, & Munsterman, 2002; Kalven & Zeisel, 1966; Sandys & Dillehay, 1995). However, it is necessary to determine if this apparent difference between real and mock jurors is real.

3 Leniency Asymmetry Effect: Is There a Difference Between Mock and Actual Jurors?

In a recent study involving 279 jury-eligible community members in Taiwan, Huang and Lin (2014: 370–371) reported that jurors’ post-deliberation acquittal rate (71.7%) was significantly higher than the pre-deliberation acquittal rate (58.8%), suggesting a leniency effect as a result of deliberation. In fact, the acquittal rate was significantly higher in juries who were required to return a unanimous verdict, compared to those who were able to return a majority verdict. The prosecutor’s case strength and the credibility of the defence case were the strongest predictors in both pre- and post-deliberation verdicts, with a positive correlation between jurors’ aversion to wrongful conviction and their acquittal rate, post-deliberation (Huang & Lin, 2014: 371).

Huang and Lin (2014: 371) also found a strong majority effect in that the unanimous verdicts in 11 out of 14 juries reflected the initial majority position. As well, among the six hung juries, ‘the majorities won more votes in two juries, with four juries maintaining the initial vote’, while all the final majority verdicts reflected the initial position of the majorities. Huang and Lin (2014: 374, 375) concluded that deliberation ‘not only has the effect of increasing jurors’ aversion to wrongful conviction and their acquittal votes … but also the effect of promoting the association between the two’ and that ‘deliberation led more jurors to be persuaded to switch from conviction to acquittal than vice versa’.

provides pro-acquittal jurors with a strategic advantage during debate in the jury room. Jurors favouring acquittal need only raise a single reasonable doubt in the minds of pro-conviction jurors, whereas jurors arguing for conviction must refute all reasonable doubts in the minds of pro-acquittal jurors. (MacCoun & Kerr, 1988: 26; citing Nemeth, 1977)

In sexual assault trials, for example, these ‘reasonable’ doubts often arise from the defence narrative which typically relies on widespread beliefs about appropriate and inappropriate victim behaviours, as discussed in Parts 4 and 5, below.

MacCoun and Kerr (1988) found that there was a leniency bias (that is, verdicts favouring acquittal) in juries that had deliberated under the reasonable doubt standard, compared to juries that had deliberated under the preponderance of the evidence standard used in civil trials. Their results suggested ‘that deliberation tends to amplify the effects of these instructions’ (MacCoun & Kerr, 1988: 30). They also found a leniency shift towards acquittal independent of the standard of proof manipulation, indicating that deliberation, of itself, produces a leniency bias but as a result of what aspects of deliberation they were not able to tell.

routinely relied upon by jurors who sought to convince peers against conviction and the inability to be sure of guilt on the basis of the evidence was by far the most common reason offered by those who shifted preference towards acquittal. … [J]urors who campaigned for a not guilty verdict routinely asserted that conviction required 100% certainty. … It is striking that only in a very small number of juries was this interpretation ever questioned.

By contrast, Sandys and Dillehay’s (1995) study with actual jurors found that of the juries that were evenly divided at the beginning of deliberation, 71% ended up convicting, suggesting, instead, a severity effect. After interviews with 142 jurors who had served on felony trials, Sandys and Dillehay (1995) reported findings that were remarkably similar to those of Kalven and Zeisel (1966) in that there was ‘a significant relationship between first-ballot votes and final verdicts’, with the final verdict being consistent with the initial majority in 93% of trials (Sandys & Dillehay, 1995: 184). These results confirm that by the time the first vote is taken in a criminal trial, ‘the jury has settled on a decision’ and only rarely will it be altered by subsequent deliberations (Sandys & Dillehay, 1995: 188).

While Sandys and Dillehay (1995: 185) found that final verdicts were consistent with majority first-ballots in 75% of cases, evenly split juries produced guilty verdicts in 71% of cases, acquittals in 21% of cases and hung juries in 8%. These results do not support the leniency asymmetry effect found in simulated jury studies, nor do the results of Hannaford-Agor et al. (2002) who, in a study of 382 criminal trials, found that 23 out of 44 (52.3%) of evenly split juries produced guilty verdicts.

Given the differences between simulated jury studies and studies involving actual jurors, it is necessary to ask, do actual juries display a leniency effect? This question is particularly important for understanding outcomes in sexual assault cases. It was addressed by Devine et al. (2004) who examined the predictive validity of jurors’ initial vote on final jury verdicts by studying 79 criminal juries to determine whether a leniency asymmetry effect exists. The authors predicted that juries with a two-thirds majority, pre-deliberation, would follow the majority view by the end of jury deliberation, while juries without a majority prior to deliberation would acquit in most cases.

Devine et al. (2004: 2080) found that the strength of both prosecution and defence evidence ‘were strongly related to guilty verdicts’, while evidence presentation quality and severity of the primary charge were ‘positively associated with conviction’, compared to defendant testimony which was ‘negatively associated’. As had been predicted, ‘the percentage of jurors favoring conviction on the first deliberation vote was very strongly related to final verdicts … as was the shift in the number of jurors favoring guilt between the first and second votes’.

As expected, 94% of juries acquitted when they exhibited a two-thirds pro-acquittal majority prior to deliberation, while 90% of juries with a two-thirds pro-conviction majority delivered a guilty verdict. On the other hand, the expectation that juries without a two-thirds majority would acquit was not reflected in their results. Instead of acquitting, 75% of these juries (that is, juries with 50, 58 or 42% of jurors favouring conviction) delivered guilty verdicts, irrespective of jury size (Devine et al., 2004: 2081).

As well, reversed verdicts were rare with only 5% of juries producing a final verdict opposite to that favoured by the majority at the outset of deliberation. As a result, Devine et al. (2004: 2089) suggested that ‘the operative decision scheme in real juries might be characterized as “two-thirds majority, otherwise convict”’ (compared to mock juries) which suggests that real jurors exhibit a severity bias.

Devine et al. (2004: 2092) concluded that three independent studies, including their own, found ‘much less leniency bias in actual juries than would be expected from the substantial research involving mock juries’. In each of these three studies, close juries (those with, or close to, a 50/50 split) convicted 50–75% of the time. In a later study, in which jurors from 103 criminal trials were surveyed, Devine et al. (2007) reported that 56% of the juries in cases in which the first ballot vote was close convicted the defendant, concluding that this was further evidence against a leniency effect on the part of real juries, although only 16 juries met the criteria for a non-two-thirds majority in the study.

Nonetheless, these results raise the question as to why mock jurors would act differently to real jurors, since they are drawn from the same population of people eligible for jury duty. The results also ‘evoke longstanding arguments about the alleged invalidity of the mock jury method’ (Kerr & MacCoun, 2012: 597), with explanations for the difference focusing on the artificiality of simulated jury studies, the simplified materials used (such as written case summaries) and the non-court, laboratory setting, although the leniency effect has been seen in simulated jury studies that used short, written materials, as well as realistic videotaped trial simulations (MacCoun & Kerr, 1988). On the other hand, studies of real juries assume that jurors’ post-trial accounts of their juries’ initial votes and final verdicts are accurate.

3.1 Severity or Leniency Effect: How Do Real Juries Actually Behave?

In order to determine whether a leniency effect is an artefact of mock jury studies and whether actual juries exhibit a severity effect, Kerr and MacCoun (2012) re-analysed the data reported by Sandys and Dillehay (1995), Hannaford-Agor et al. (2002) and Devine et al. (2004).

By identifying the methodological errors in the above studies, Kerr and MacCoun (2012: 588–589) concluded there were ‘potential biases’ in the coding of the first ballot votes. In other words, the primary explanation for ‘the apparent divergence of laboratory and field evidence on the leniency asymmetry’ appears to be due to the assumption that the category of ‘undecided/abstain’ votes equated to ‘not guilty’ votes such that the two categories were collapsed into one.

Kerr and MacCoun (2012: 590) consider that there is no empirical or logical reason for this assumption so that when a first vote is taken, the undecideds/abstainers should either be excluded or should be equally distributed between guilty and not guilty votes in a study. The up-shot of the misclassification means that evenly split juries in a study would, with re-classification or by exclusion of the undecideds/abstainers, turn into pro-conviction juries, thus changing the results reported by the study. Since only evenly split juries are used as the parameter for assessing a leniency effect, a pro-conviction jury that is misclassified as an evenly split jury that ends up convicting represents a false measure of severity and the non-existence of a leniency effect.

- i.

initial majorities nearly always prevail (93.2 and 94%); and

- ii.

for the majorities that did not prevail, they were more likely to be pro-conviction majorities that ended up acquitting.

Overall, the severity effect evident in the studies of Devine et al. (2007), Sandys and Dillehay (1995) and Hannaford-Agor et al. (2002), as a result of the misclassification of undecideds/abstentions, was ‘attenuated or eliminated’ when re-coding methods were used (Kerr & MacCoun, 2012: 591). The asymmetry was reversed in relation to the data of Devine et al. (2004) and Sandys and Dillehay (1995) (although less dramatically in the latter), while a symmetric effect for split juries was found with the re-coding of the data of Hannaford-Agor et al. (2002). Thus, the so-called severity effect reported in these studies ‘can plausibly be attributed, at least in part, to a biased coding assumption’ (Kerr & MacCoun, 2012: 595).

The leniency effect in the above studies was not as large as that found in MacCoun and Kerr’s (1988) study of mock jurors. Even so, there are good reasons to re-consider the status of mock jury research since such studies assemble large numbers of jurors who view the same trial compared to actual juries which represent ‘one jury per case’ (Kerr & MacCoun, 2012: 598). Thus, it is likely to be harder to test for a leniency effect in real juries. As well, mock jury studies typically create case scenarios where the evidence is equivocal or close in strength (as between prosecution and defence) in order to test for the effect of specific types of evidence or judicial instructions. And it is in close cases where a leniency effect is most likely to be detected (Kerr & MacCoun, 2012: 598), rather than being apparent in all cases. By comparison, actual jury trials are likely to involve cases with relatively strong evidence for the prosecution given the discretionary decision to prosecute and the resources involved (Kerr & MacCoun, 2012: 598) so that a comparison of mock jury trials and real trials must take into account that these trials are not comparable in terms of case strength.

- i.

a higher conviction threshold compared to judges;

- ii.

a majority effect, with acquittals more likely to prevail than convictions; and

- iii.

a leniency asymmetric effect as a result of juries being prone to acquit, particularly when the prosecution and defence evidence is close in strength.

In other words, all three findings have major implications for sexual assault trials, particularly those relying mostly on the complainant’s word against that of the defendant. It is possible that sexual assault trials with little or no supporting evidence are particularly prone to the leniency effect due to widespread rape-supportive beliefs within Western cultures and the influence of RMA on jury outcomes (see Parts 4 and 5, below).

3.2 Systematic Biases in Jury Decision-Making

One clear observation from jury research is that while jury decision-making is imperfect, it is not randomly so in that ‘humans consistently exhibit systematic biases in their judgments’ (Kerr, MacCoun, & Kramer, 1996: 687). In other words, jurors ‘arrive at court fully loaded with prototypes … heuristics … and “commonsense notions” of justice and fairness’ (Finkel, Burke, & Chavez, 2000: 1113).

Jurors’ biases include imprecision in the assessment of evidence, ‘sins’ of commission whereby juries ignore a judicial warning which warns them not to reason in a particular way, and sins of omission (Kerr et al., 1996). These biases may be due to a number of factors such as the use of heuristic processing, as opposed to more effortful, systematic processing when assessing the evidence in a trial (Chaiken, 1980; Chaiken and Trope, 1999; Chen, Shechter and Chaiken, 1996; Eagly and Chaiken, 1993; Winter and Greene, 2007) and misunderstandings of judicial directions. The significance of heuristic versus systematic processing in jury trials is discussed in Chapter 3.

Because jurors find themselves in an out-of-the-ordinary, unstructured situation where they are under pressure to reach a unanimous decision with strangers, ‘they tend to primarily consider the information that supports the group’s existing preferences’ (Gordon, 2015: 40; citing Straus, 2011) while ‘groups seem to have difficulty accessing information that is not widely shared among members’ (Kerr et al., 1996: 714).

This tendency to focus on evidence that supports the majority position is supported by the story model proposed by Hastie, Penrod, and Pennington (1983). Where a preference is favoured by a majority of jurors, the story model, discussed in detail in Chapter 3, would propose that the story constructed by jurors reflects the majority position which then impedes jurors from considering other evidence that supports an alternative story and verdict, thus reinforcing individual biases and perpetuating information bias (Gordon, 2015: 41). Indeed, enhanced bias or ‘sins of commission by groups operating under majority-rule decision’ are more likely in groups, such as juries, where the decision-making task has ‘no clearly shared conceptual scheme for defining right or wrong answers’ (Kerr et al., 1996: 714). One could then conclude that group decision-making ‘is ill-advised’ for the important job that juries undertake (Kerr et al., 1996: 714).

Kerr et al. (1996: 687) consider that there is no simple answer to the question whether individuals are more biased than groups, although it is hypothesised that groups are more susceptible to extra-legal information, such as racial or sexist biases, and other misconceptions because of the persuasive nature of jury deliberation (Davis, 1980; Kalven & Zeisel, 1966). In fact, Davis’ (1980) social decision scheme (SDS) model proposes that members of a group make decisions through social decision schemes, such as a ‘majority rules’ decision scheme, which is consonant with the majority effect and the leniency asymmetry effect discussed above. Nonetheless, SDS theory is ultimately a mathematical model which seeks to predict group behaviour based on, first, where group members begin their deliberation and, second, the processes by which group members discuss their preferences to reach a group decision. It is, therefore, a theory that may not be able to account for the complexities of group dynamics.

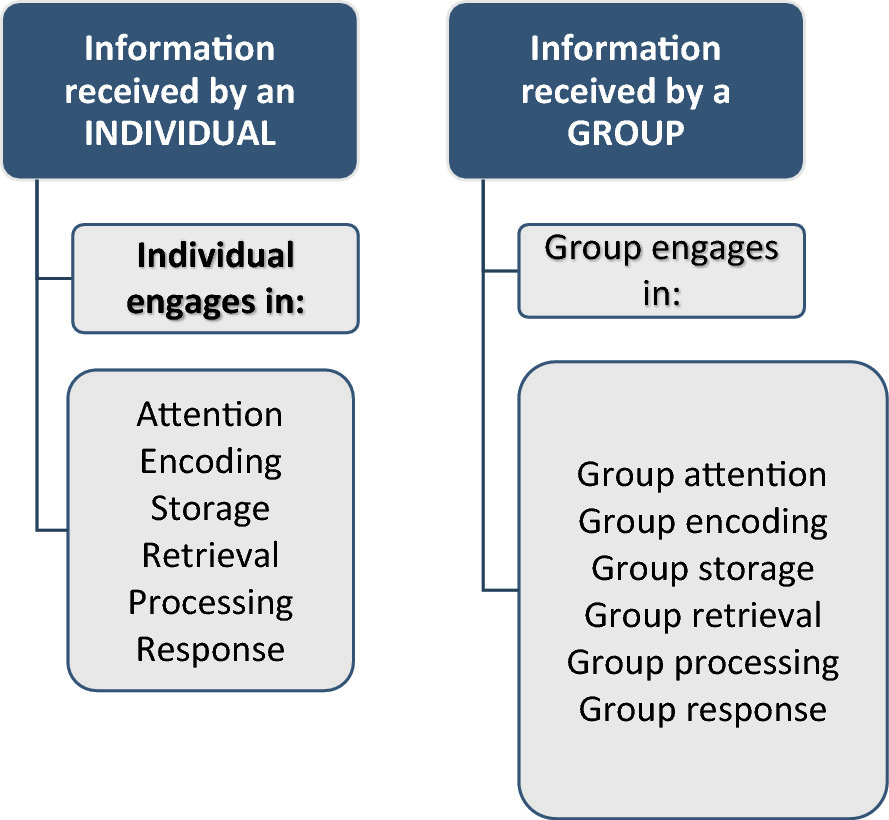

From individual processing to group processing (based on Kerr et al., 1996)

As well, the tasks of the group expand dramatically with group decision-making, including maintenance of group harmony, relationships and attention, the consideration of multiple points of view and style of deliberation. Group discussion may enhance or hinder retrieval of information and enhance or correct individual biases, as well as having a corrective effect on individual misunderstandings of the facts and judicial instructions (Goodman-Delahunty, Cossins, & Martschuk, 2016).

It is possible that jury deliberations also reflect less responsibility by individuals as they begin to work as a group and play follow the leader, particularly as ‘status hierarchies, group cohesion, group norms and group roles’ emerge and develop (Gordon, 2015: 14). With high status individuals tending to lead group discussion, jurors ‘participate in group discussion at markedly different rates’, with higher status jurors being more influential in guiding the deliberation (Gordon, 2015: 15).

While juries are expected to represent community norms, a group of twelve people is unlikely to represent all possible sex, gender, racial, ethnic, cultural and religious norms in any given community. Even where diversity is present in a group, the phenomenon of group conformity means that group members may adopt others’ incorrect decisions or interpretations, with human brains containing neurons for mimicking the actions of others (Gordon, 2015: 27–28). Thus, not every juror will necessarily engage in systematic, thoughtful, rational reasoning with some making quick, heuristic judgements, others not paying attention at all (referred to as ‘social loafing’: Simms & Nichols, 2014) and others going with the majority view.

Certainly, the effect of the majority choice on group behaviour, as documented in some studies (Clark, 2001; cited in Gordon, 2015), explains why majority first votes tend to prevail as the final verdict, suggesting that minority jurors eventually conform with the thinking of the dominant group. In a sexual assault trial, the extent to which individual jurors adhere to particular rape myths may lead to quick, heuristic judgements and dominant group norms based on these rape myths.

Gordon (2015: 35–37) argues that training jurors is the answer to the disadvantages of group dynamics, that is, training in ‘effective group decision-making strategies and … collaboration’ and information sharing in order to reduce the effect of status and social conformity and to ensure that jurors do not waste time figuring out how to work as a group, time better spent on analysing the evidence and applying the relevant judicial directions. Such training would require a large amount of resources, give the number of jurors who are called up for jury duty annually.

3.3 Is the Leniency Effect More Pronounced in Sexual Assault Cases Because of Jurors’ Adherence to Rape Myths?

Compared to other criminal trials, sexual assault trials are more likely to be close cases because of a lack of the type of corroborating evidence that is typically admitted in other criminal trials, such as medical evidence of injuries, eyewitness evidence, DNA evidence, fingerprint or other forensic evidence. If the prosecution’s chief witness is a child, his or her verbal and mental development can place them at a great disadvantage when giving evidence and being cross-examined (Cossins, 2009) which impacts on the quality of her/his evidence. In other words, sexual assault cases give rise to numerous doubts which are likely to be filtered through jurors’ misconceptions about women, children and sexual assault.

Indeed, confirmation bias has been shown to influence people’s assessment of the behaviour of others. Confirmation bias ‘is the tendency to bolster a hypothesis by seeking consistent evidence while minimizing inconsistent evidence’ (O’Brien, 2009) and has been confirmed in a number of experimental studies (Ask & Granhag, 2005; Hergovich, Schott, & Burger, 2010; Jonas, Schulz-Hardt, Frey, & Thelen, 2001; Jones & Sugden, 2001; Klayman, 1995; Kassin, Dror, & Kukucka, 2013).

For example, in an early study, Langer and Abelson (1974) recruited 40 clinical psychologists (from different theoretical backgrounds) who viewed a videotaped interview of a man with one of the authors. Half of the clinicians were told that the man was a job applicant while the other half were told that he was a patient. When the clinicians were asked to evaluate the man, the therapists with a traditional approach to therapy described the man as significantly more disturbed when they thought he was a patient compared to when they thought he was a job applicant.

If confirmation bias can occur with psychologists (Hergovich, Schott, & Burger, 2010; Langer & Abelson, 1974), police investigators (Ask & Granhag, 2005) and forensic scientists (Kassin et al., 2013), it is just as likely to occur in a jury when individual jurors believe in rape myths. A particular bias or heuristic cue—for example, that ‘women who wear revealing clothing are asking for it’—may then be the filter or lens through which a complainant’s evidence and credibility and other trial evidence is assessed in order to confirm the bias.

a cycle may occur such that people notice information that corroborates a double standard, which solidifies their belief in its existence, thereby making it all the more likely that they will continue to notice information that corroborates the double standard. (ibid.: 24)

As discussed in the next chapter, numerous studies reveal the extent to which laypeople endorse rape myth acceptance (RMA) and misconceptions about children and CSA, thus increasing the likelihood that in any one jury, a proportion of jurors will adhere to some of these myths and misconceptions. For example, the literature reveals that the higher an individual’s level of RMA, the more likely s/he will blame the victim, and the less likely s/he will perceive the victim to be credible and the defendant to be culpable (Stewart & Jacquin, 2010). In fact, there is a positive correlation between relatively high levels of RMA and a tendency to acquit in sexual assault trials (Dinos, Burrowes, Hammond, & Cunliffe, 2015).

Although there is a leniency asymmetry effect in criminal trials, generally speaking, it may be too simplistic to conclude that a jury acts in exactly the same way as an individual when presented with a vignette about rape outside of a criminal justice setting. Jurors in a real trial engage in deliberation which may either modify or enhance the effect of any rape myths that exist within the jury room. Thus, it is necessary to understand the underlying psychological reasoning processes that might lead from RMA to an acquittal.

Is there a causal relationship between high levels of RMA and acquittals in sexual assault trials? Even asking the question presupposes that all sexual assault cases are identical in terms of evidence strength and complainant credibility and that RMA is the only factor that affects jury decision-making.

To answer this question, it is necessary to review the literature on the factors that affect jury verdicts in sexual assault trials. While there is a large literature on the relationship between the characteristics of jurors, victims and defendants, and criminal trial outcomes, the discussion in the next chapter focuses on sexual assault trials.

This discussion takes a closer look at the factors that have been shown to predict verdicts in sexual assault trials in order to explore whether the leniency effect could be more pronounced in those trials. It begins with studies that examine the legal factors that affect convictions in sexual assault cases, followed by a summary of the literature on jurors’ and laypeople’s perceptions of the behaviour of rape complainants and the literature on RMA in the general population.