Since the late seventies, Arnold had changed his agent, his house, his dress style, and his social ambience—everything but Maria. "When I was traveling back and forth, and going here and there, people used to say, 'I can't believe Arnold lets you do that,'" said Maria. "My whole example was my father, a man who not only let my mother 'do it' but encouraged her to do it. As I became kind of more aware, I realized that that wasn't really the norm. Most husbands didn't want their wives out conquering the world."

Arnold had always wanted a traditional, stay-at-home wife, but his girlfriend was an ambitious, driven woman who cared about her career as much as he cared about his. What he gained was her sophisticated sense of the world of power and politics and just how things worked in the world. In that respect, Maria was far wiser than Arnold. As shrewdly as he had learned to disguise it, he still had not shaken free of his provincial roots. Maria, just like her mother, could be a merciless goad, picking away at Arnold's supposed foibles. But it was Eunice who, as Arnold saw it, was one of the keys to predicting how Maria would be as a wife and mother. He saw the emotional energy that Eunice put into her children, and he figured that Maria would do the same.

As the years went by, Maria's career and work schedule had only increased, and she was gone much of the time. She had moved on from PM Magazine to become a junior reporter for the low-rated CBS Morning News and by the spring of 1985 occasionally flew back to New York to cohost the troubled program. There was even talk that if the much-derided Phyllis George left the show, Maria might have a shot at being a regular host.

For years Arnold had said privately that he would marry Maria one day, but that day had always been out there far in the future. "Maria fell for him and was in love with him," said one close observer. "She was getting older, and she couldn't be in that position forever. He went out and saw other people. I

think he valued her. He appreciated where she came from. He had to make a decision. Am I going to have this or not.^"

Maria says that Arnold asked her twice to marry him before she said yes. In the late spring of 1985, Lorimer was visiting Arnold in Los Angeles. It was about midnight and the two friends were relaxing in the Jacuzzi. Lorimer was twenty years older than thirty-seven-year-old Arnold. His friend was a man whose judgment Arnold trusted on all sorts of levels.

"Arnold, you've been going with this girl now for eight years," Lorimer said. "The relationship has stood the test of time. She has a career, you have a career; you're very successful, and nobody could accuse you of marrying the girl for her money. You don't need anybody's money. You don't have to work for the rest of your life. But you've got to experience all of life's processes. And that means marriage, stable home, children, and grandchildren. You've got to make the move and ask her to marry you."

"Yeah, yeah, thanks," Arnold said, and they went on to talk of other things, as if he had dismissed his friend's advice. However, Lorimer had approached the matter in the only way that would have caught Arnold's attention. It was not about being fair to Maria and all the years she had been waiting for him. It was not about looking like a solid citizen, especially if he intended to run for office one day. It was about Arnold's experiencing life to its fullest. His fear had always been that marriage would wall in his life and close down his future, and here Lorimer was telling him just the opposite. If he wanted to live life at its deepest, he had to get married.

In August, Arnold and Maria flew to Austria to visit his native village. Going back to Thai was a way to place his boots solidly on the earth, to sense not only how far he had gone but how much he remained. He rented one of the boats on the shore of the tiny Thalersee and rowed out into the middle of the lake. And there he asked Maria to marry him, and there she said yes.

The couple had barely returned to the United States when CBS offered Maria the coveted position of cohosting CBS Morning News with Forrest Sawyer. Her professional dream was to be the cohost of a network morning show, but her personal dream was to marr\' Arnold. Accepting the CBS position would mean that she would have to move to New York City. "I had to make a wrenching decision," she told The New York Times. "It was the job I'd always wanted. But I had worked a long time at that relationship, and I had just finally gotten it where I wanted it, and all of a sudden, I was faced with moving 3,000 miles away and pursuing a very demanding job. But I knew that if I didn't take it, there were other people who would."

What Maria did not tell the Times was how difficult it was to be away from Arnold when she feared that there were other women approaching her fiance.

It did not matter that they were engaged. "Girls were always chasing him," said her friend Theo Hayes. "I went to restaurants with them where girls would walk by the table and slip a piece of paper under his hand while Maria was sitting there with a big engagement ring on. I'm telling you, these women were throwing themselves at him. I can remember we were walking in Georgetown one night. My husband and Arnold were in front, and Maria and I were five steps behind, and it had just happened in this restaurant. This woman had heaved her bosoms in his face while we're eating and gave Arnold her card. And I said to Maria, 'How do you handle it.^' She goes, 'What can I do.?'"

As much as she disguised it, Maria had been more the pursuer than the pursued with Arnold. She had waited close to a decade for him to ask for her hand. Arnold encouraged her to accept the CBS offer even though it meant he would see her primarily only on weekends. Her program was a distant third in the ratings, under extreme pressure to do better. She lived in a hotel room, and during the week practically all she did was work. She had almost no social life in New York.

"Shriver does not look like she cares about the answers to any questions except, 'What time will Arnold be home.''' and 'Where's my brush.?'" the acerbic Tom Shales wrote in The Washington Post. "She sucks in her cheeks and deflates her face, looking a little like one of those cartoon characters who got slipped a dose of alum." If anything, Maria cared too much and was trying too hard.

Maria was cohosting the program at a time when women had to prove that they were as serious as their male colleagues. When she was criticized for posing for the cover of Harper's Bazaar with her colleague Meredith Viera, she said that she had done so to please the CBS publiciry^ department. There had been no criticism when ABC's Peter Jennings and NBC's Tom Brokaw appeared on the cover of GQ. Maria's impending marriage to Arnold was an almost irresistible opportunity to promote herself and give a jolt to the anemic ratings, but she refused to talk on air about Arnold. Off air, she enthusiastically threw herself into planning a large wedding, fully in the Kennedy family tradition. On her last Friday as a single woman, she told the audience, "I'll be taking a few days off."

Previous generations of the Kennedy men had married women who were socially their superiors and would advance them in the world. The women had generally married men who tied themselves to the fortunes of the family. Maria's father had been employed by Joseph P. Kennedy when he met Eunice. The closest parallel to Maria's own marriage was that of her aunt Patricia. She had married the British-born actor Peter Lawford, who introduced

his brother-in-law Senator John F. Kennedy to the Hollywood world. Lawford had largely dissipated himself with drugs and alcohol before the couple became the first of many Kennedys to divorce.

Arnold was not subordinating himself to the fortunes of the Kennedys or the Shrivers. He neither needed nor wanted the family imprimatur to make his way in the world. Nor was Maria consciously subordinating herself and her fortunes to those of her husband. She planned to keep her last name, and she considered the proud Shriver heritage the essence of her being. She insisted that the marriage vows be changed from "man and wife" to "husband and wife," signifying that in her mind the bonds that united her with Arnold were the same that united Arnold with her.

For all their concern for the poor and the needy, the Shrivers had a sense of social order and class worthy of the Windsors. They consciously used people for their various causes and charities, and they had their own ever-changing hierarchy, the pinnacle of which was formed by those who sat closest to them and contributed greatest to their advance. Many of Arnold's friends and other wedding guests got a rude introduction to that reality when they discovered that there was a wedding party beforehand at the Shrivers' Hyannis Port home to which they were not invited.

The five-hundred-person guest list itself included the close friends of the bride and the groom, but it was also full of media people who would prove extremely helpful to the couple in the years that followed. Oprah Winfrey, Maria's former colleague in Baltimore, had her own talk show and had been nominated for an Academy Award as Best Supporting Actress for her role in The Color Purple. She was emerging as a most influential person, and Maria was one of her closest friends. Other guests from the media included Tom Brokaw, Diane Sawyer, and Barbara Walters, whose paths would cross again and again with Arnold and Maria's.

Maria's bridesmaids included several of her cousins and close friends: Renee Schink, Charlotte Soames Hambro, Theo Hayes, Wanda McDaniel Ruddy, and Roberta Hollander. As Arnold already knew, these women were as close to Maria as his bodybuilding buddies were to him. She talked to them all the time and confided to her girlfriends the way he rarely did to anyone.

As Arnold stood in front of the St. Francis Xavier Church in Hyannis on April 26, 1986, he was with the two people in the world who mattered the most to him, his bride and his mother. Maria was her mother's daughter in that often she did not care how she looked. She had learned to pay attention to her dress, because she had to if she wanted to succeed in the world. A wedding dress was something else, and like her mother before her, she took great

care to have an exquisite dress. The designer of the gown, Marc Bohan, was a guest at the wedding so that he could appreciate his elaborate handiwork of white silk and lace.

Arnold's mother had originally not been happy with her son's choice of a bride. Since his father's death, Arnold had made sure that his mother had a life of ease and comfort, and she may have worried about losing that. She may also not have felt comfortable with Maria, who neither spoke her language nor had the convivial warmth of so many Styrian women. There was another reason his mother blanched when he told her of the engagement. "She felt originally that she may lose the attention that I've given her," said Arnold.

Aurelia was an uneducated village woman, but she had a natural grace and digniry'. She looked a match for any of the Kennedy ladies in her elegant violet dress, pearls, pink shoes, and mink coat. As proud as she appeared and as apprehensive as she probably felt, she was Arnold's mother and desersed to be treated with the highest respect. Jackie Onassis, whose sense of manners did not end at the dinner table, invited Arnold's mother to her Hyannis Port house. "It's amazing how nice she is, and how nice they were to me," she told Arnold after\vard. "And Teddy was the one that helped me out of the church and offered his arm."

What Aurelia did not tell her son, and several of the guests had noticed, was how rudely some members of the Kennedy family treated her, not even granting her the minimal courtesy of greeting the mother of the groom. Arnold did not notice and even now finds it hard to believe, but his friends observed and remembered. Maria is equally adamant that her mother-in-law was royally treated. "I don't know if you're talking about three or four people who might have seen her alone for two minutes with no one to talk to who could have said that.' Yes. If she had to wait for five minutes to get a car, could that have happened.^ Yes. But you know, I've never seen in my lifetime a woman treated as a queen as that woman was. From the minute I met her to the minute she was buried, she was a queen."

The guest who was the most discussed was one who was not there, former secretary-general of the United Nations Kurt Waldheim, who was in the last days of his campaign for the Austrian presidency. When Arnold invited Waldheim, he did not know that within a few weeks the World Jewish Congress would expose that Waldheim had been posted to a unit that had been involved in numerous atrocities in the Balkans during World War II. In his official appraisal of the charges, Austrian President Rudolf Kirchschlaeger said that although Lieutenant Waldheim did not appear guilty of war crimes, he surely had knowledge of the "reprisal actions against the partisans."

Waldheim had sent a gift that was reason alone for him to be much discussed, a Hfe-size papier-mache statue of Arnold and Maria in native Austrian dress. Except for the prominence of the subjects and the overwhelming size, the statue looked like something bought in a souvenir shop. The guests at the reception grew strangely quiet when the Austrian contingent unveiled the bizarre sculpture. "Maria looked like Gloria Swanson in 'Sunset Boulevard,'" one of the guests told the Chicago Tribune. No one probably would have even commented on the Waldheim gift if Arnold had not made such a point of it during the reception. "My friends don't want me to mention Kurt's name, because of all the recent Nazi stuff and the U.N. controversy," said Arnold, as Andy Warhol recorded the words in his diary, "but I love him and Maria does too, and so thank you, Kurt."

Arnold is a loyal friend, a virtue that allows him to forgive what should not be forgiven, and cast his eyes away from matters that should be faced. He is not a man who believes in apologies, and he has never publicly regretted his defense of Waldheim.

Arnold's sense of loyalty was also displayed at its best that wedding weekend. His guest list was not jammed with studio executives and others invited because it might advance his career. His list was full of old friends and relatives. Franco Columbu, was his best man. Paul Graham, who ten years before had left California after spending time in prison, flew in from Australia. Not only did Albert Busek arrive from Munich, but he brought his wife with him. Mrs. Busek was in the advanced stages of multiple sclerosis. She was in a wheelchair and had a difficult time holding down her food, but Arnold insisted that she be at his wedding. Although George Butler was invited, Arnold had grown suspicious enough of the man whose photography had helped make him celebrated that he had his camera confiscated. "That was a caddish thing to do," said Butler. "It was Arnold at his worst."

Other cronies were invited and played prominent roles. "I'm having Jim Lorimer do the reading for me, because he's the only one of my friends who can read," Arnold joked to his friends. Sven Thorsen was an usher. After his impromptu speech at the Commando premiere, Arnold might have retired him from the speaker's platform, but a friend was always a friend. Sven had his say. "In Denmark, and my wife here is my witness, the household for a man needs three things—a vacuum cleaner, a dishwasher, and a woman," Sven said, in his foghorn voice. "And in that order."

"Who the fuck is your friend.'"' Senator Edward Kennedy asked after the laughter died down. "Ah, he's from Denmark," Arnold replied. "He's a comedian. I don't like him."

Except for a modern new church, the bucolic village of Thai, Austria, looks much the same as it did when Arnold Schwarzenegger was born here in 1947. (Laurence Learner)

RIGHT: Sixteen-year-old Arnold with two friends, Karl GerstI (right) and Willi Richter, at the lake in Thai in the summer of 1963. (Alfred GerstI)

I

LEFT: Schwarzenegger and his Austrian mentor, eighty-one-year-old Alfred GerstI, in the governor's Sacramento office in January 2005. (Alfred GerstI)

No other bodybuilder did Arnold admire as much as the South African champion Reg Park. (Jon Jon Park)

ABOVE: Arnold with his bodybuilding mentor Joe Weider at the Mr. Olympia contest in October 2003. (AP/Wide World)

BELOW: Arnold and Joe Gold bear-hug at the legendary Gold's Gym in Santa Monica, California. (Photograph © George Butler/Contact Press Images)

cmw^'^:^^

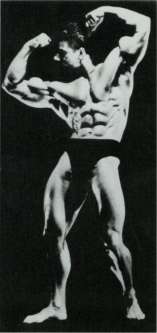

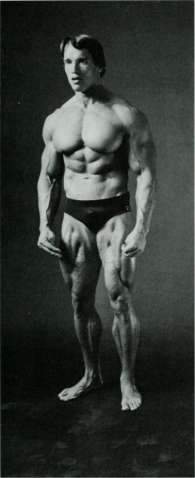

Arnold Schwarzenegger developed himself into what author Charles Gaines called "very possibly the most perfectly developed man in the history of the world." (Photograph © George Butler/Contact Press Images)

Arnold took steroids, but the key to his greatness was that he worked out harder than any other bodybuilder. (Photograph © George Butler/Contact Press Images)

Arnold found joy in every aspect of bodybuilding. (Photograph © George Butler/Contact Press Images)

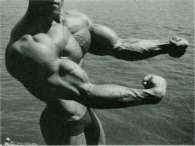

It took endless workouts to develop Arnold's twenty-two-inch arms. (Photograph © George Butler/Contact Press Images)

Arnold was a showman who knew how to display his body better than any ot his competitors. (Photograph © George Butler/Contact Press Images)

Arnold's legs are the last part ot his body that he fully developed. (Photograph © George Butler/ Contact Press Images)

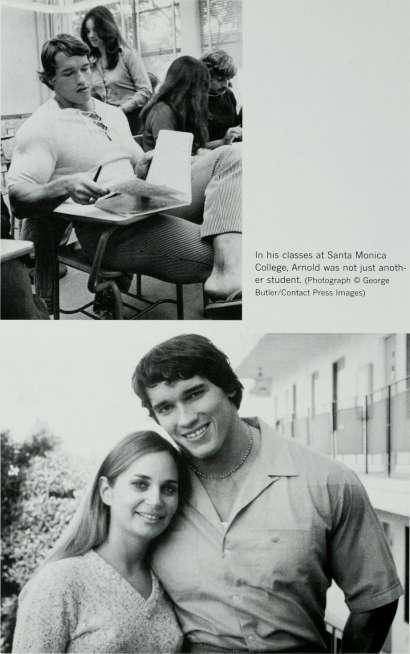

In his classes at Santa Monica College, Arnold was not just another student. (Photograph © George Butler/Contact Press Images)

Arnold tell in love with Barbara Outland and lived with her for five years in the early 1970s. (Barbara Outland Baker)

Arnold met Maria Shriver at the 1977 Robert F. Kennedy Pro-Celebrity Tennis Tournament, where he played tennis with football great Rosie Grier (AP/Wide World)

If Maria Shriver introduced Arnold to a world he had never seen, he introduced her to a world new to her as well. (Photograph © George Butler/Contact Press Images)

Maria accompanied Arnold when he became an American citizen on September 15. 1983. (AP/Wide World)

Arnold's publicist Charlotte Parker was a key player in his rise to stardom. (Charlotte Parker)

For most ot his career, Lou Pitt (center) was Arnold's agent. Also seated here is director James Cameron. (Lou Pitt)

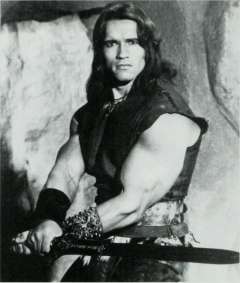

Arnold's first starring role was as Conan the Barbarian. (Photofest)

The Term/nafor films turned Arnold into a worldwide icon. (Photofest)

Arnold, his nephew, and his closest friends on his wedding day. Left to right: Patrick Knapp, Franco Columbu, Albert Busek, James Lorimer, and Sven Thorsen. (Private photo)

On their wedding day, it was hard to tell who was happier, Maria or Arnold. (Private photo)

Maria waltzing with Arnold on a broken toe at their wedding on April 26, 1986. (Private photo)

Arnold often returned to Austria to be with his mother, Aurelia Schwarzenegger. (Photograph © George Butler/Contact Press Images)

Arnold danced with Sylvester Stallone at the 1990 Cannes Film Festival, but secretly Stallone was trying to destroy his rival. (AP/Wide World)

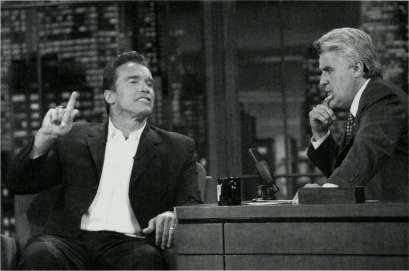

Arnold announced his entry into the California recall election to Jay Leno on The Tonight Show in August 2003. (AP/Wide World)

At a speech in Long Beach,a protestor threw an egg at Arnold. (Bruce Murphy)

LEFT: Arnold and Maria embrace on a victorious election night, October 7, 2003. (AP/Wide World)

BELOW: Arnold kisses Maria while their children (left to right), Christina, Katherine, Patrick, and Christopher, wait just before he takes the oath to become the thirty-eighth governor of California. (AP/Wide World)

Arnold speaking at the Republican National Convention on August 31, 2004, in New York City. (AP/Wide World)

Maria had broken her toe in her New York apartment, so she put on sneakers to dance with her husband. Neither the bride nor the groom knew how to waltz, and they had taken private lessons to be ready for the day. They moved gracefully around the heated tent to the music of Peter Duchin. The newly-weds exuded happiness, Arnold as much as his bride.

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

Raw Deals

In the summer of 1986, the newlyweds moved into a splendid $4 million house on Sunset Boulevard in Pacific Palisades eminently suitable for one of the greatest of Hollywood stars. The seven-bathroom, seven-bedroom home had an open, airy feeling; and spacious grounds with a swimming pool, a fountain, and a tennis court adjacent to Will Rogers Park. For the first few months, Arnold enjoyed the new house with his bride primarily on weekends, since Maria was back in New York cohosting CBS Morning News.

Arnold rationalized that "it's only a temporary thing, but she should do it, because she'll be happy the rest of her life because she's done it." Certainly Arnold tried to make the best of it. "We fly back and forth as much as possible, and we run up thousands of dollars in phone bills," Arnold told Boston television station WBZ. "We have over-the-phone sex, but there's no way we can have children with her on the East Coast and me on the West Coast."

Arnold had married a formidable woman with her own agenda, but he had done so in his own time and in his own way. He was not going to change his habits and his pleasures. If he did, it would only be after the shrewdest, most concerted effort on Maria's part.

In most successful marriages, one partner makes a greater commitment to the marriage and expends far more emotional energ\' in making the relationship work. If this celebrity marriage did not suffer the common fate of most first celebrity marriages, it would be primarily because of Maria. Maria was a possessive woman. For close to a decade, she had held those feelings in check until Arnold finally asked for her hand. Given how much she wanted the marriage to work, it was a mark of her ambition that she was willing to be apart

from her new husband. She knew her husband and the risk she was taking, but she wanted to play out her aspirations on the highest scale.

Maria was initially devastated when she was fired from CBS Morning News on August 1. But she soon chalked it up to experience and returned to Los Angeles, to be hired by NBC. It was a fortunate move. Within three years, she was working on magazine shows during the week, anchoring NBC Nightly News on Saturday evening from New York City, and hosting Sunday Today from Washington, D.C., the next morning. For a woman who was far from a natural for television, it was an extraordinary achievement. She had become one of the top women in the business, poised for even higher positions, perhaps one day even anchoring NBC Nightly News full-time or having her own program.

"Maria worked the same hours everybody else did," said Sandy Gleysteen, her longtime NBC producer and close friend. "Around the clock, really hard." Maria tried to maintain her Shriver family ideals by agreeing to do celebrity-oriented stories as long as she could report on important social issues as well.

Some husbands would have found it intolerable to have their bride jetting across the country each weekend and working endless hours during the week, but for Arnold it was fine. He was often flying off somewhere, too, or busy on the set or elsewhere. When the couple were together, there was a special intensity.

Arnold had a well-deserved reputation for managing every last detail of his career, but compared with his wife, he was self-indulgent. "Maria is so nervous and she's the most controlling of people," said one close observer. "It's basically one control freak married to another."

Maria's mother had taught her only daughter that whatever she did was only a beginning and that nothing was ever quite good enough. Maria applied this rule most harshly to herself, but to those around her as well, especially her husband. She could be critical of Arnold in a way no one ever had been before. It could be his dress, his language, or his choice of film roles, but she was direct and forceful in her opinions.

Arnold projected onto the world an image of himself that was far more sophisticated than the reality. He had managed to obtain a business degree from the University of Wisconsin at Superior largely by correspondence, but it was far from the kind of education he would have received if he had spent significant time in the classroom. He was almost totally self-educated. Like someone who only marginally speaks a foreign language and smiles knowingly when he doesn't understand, Arnold was often in a world where he fooled people into thinking he understood more than he did.

Having grown up as a Kennedy and a Shriver, Maria had a more intuitive awareness of the world of power and wealth in America than most people. Her family used their name and position every day to do what they considered good and to advance themselves economically and politically. Arnold learned how to grasp those levers that moved American society at its highest levels. He learned to do good and to do well and to see no contradiction between the two.

Arnold was not only the great love of Maria's life but her great project. She taught him more than anyone he had ever met. "Maria took a kid and turned him into a man," said Betty Weider. "She helped him to mature. She took a rock and made him into a gem, polished him. He had the ability to learn and to be part of her. She's been like a miracle to him."

As much good as Maria did for Arnold, she also turned her hypercriticism on her husband. As much as her advice helped Arnold, it resulted in an uncertainty about himself that was not there before.

That Maria loved her husband did not mean that she had to love his friends, and she found several of them worthless hangers-on. To her mind, they brought out the vulgar, self-indulgent part of Arnold that squandered time and energy. She knew the history several of these men had with Arnold and the endless women who were adjuncts to their lives. That was the part of her husband's life that she wanted only in the forgotten past. As long as these men were around him, so also was that part of Arnold's life.

As soon as he moved into their new house, Arnold invited his close friends over for an evening. "This is our house, boys," Arnold said. At least one of them took him literally, showing up and using the pool whenever the whim hit him, but most of them thought it meant simply that they were always welcome. A couple of months later, when Maria was back in town, he invited them all over again. It was boys' night out and they were sitting out back, smoking cigars, drinking, telling dirty jokes, and using language that the Sacred Heart nuns, who educated Maria, had never heard.

In the middle of the joshing camaraderie, Maria appeared and stood before them, holding a cigarette in a long cigarette holder. "Hey, would you guys light me.''" she said, and then added: "Yeah, I want to sit here, smoking, and be tough and full of myself."

Arnold looked up at her and set down his cigar. He had his time with his friends and nothing was going to change that, not even his wife. "Hey, sweetheart," he said, looking up. "Go inside."

Maria went inside.

Arnold had done everything he could to reassure his mother that even with his new marriage, his concern for her would be undiminished. Arnold had the European attitude that his mother was welcome for as long as she wanted to stay. Every winter he invited Aurelia to Los Angeles, where she usually spent three months. When Maria invited her mother, Eunice usually came only for a few days and she was always overscheduled, running from one Special Olympics event to another, visiting her son Bobby or other friends.

Friends of the couple assert that Maria found it hard having her mother-in-law there for all those months, and it became one of the difficulties of her marriage. Maria points out that she invited the mother-in-law she refers to as "Mrs. Schwarzenegger" to come and stay, had dinner with her every evening, and tried to make her welcome. Though she does not admit how onerous it was to have Arnold's mother in her house for such lengthy visits, her discomfort seeped out in measures large enough for her friends to observe.

Aurelia was not a sweet-tempered grandmother who spent her days spoiling her grandchildren. As she saw it, her son had married far beyond his station to a woman who did not speak German. Maria did not have the convivial demeanor of many Austrian women and never seemed fully to relax. Since Maria could not cook, Arnold's mother prepared the Austrian dishes her son loved. One of Arnold's fondest memories of his childhood was the Sunday dinner of schnitzel and steamed rice, which he anticipated all week long. In Los Angeles his mother cooked the dish for him as well as other Austrian favorites. She worried that he was too thin and tried to bulk him up and lectured her beloved Arnold that he should eat first before exercising.

When Arnold was gone for weeks on a movie set, Aurelia did not call her friends in Austria to complain about her son, but she did leave the impression that she was alone in this immense house with people who could not speak to her and did not seem to care. The reality was that Arnold was the most dutiful and loving of sons who did everything he could do to give his mother the ease, comfort, and pleasure in the last decades of her life that she had not had in her earlier years. Maria understood and respected the love that Arnold felt for his mother, and if she was incapable of the oversvhelming hospitality that is the essence of the Austrian villager, she went beyond what most American women would have put up with from an often difficult mother-in-law.

Maria asserted herself in her marriage, but equality had its limits, and Arnold insisted that when thev went out with him, both Maria and his mother never

wear pants. That was a sticking point with him. If women started wearing pants Hterally, they would wear them figuratively as well, and he did not like either. Women should neither dress like men nor act like them.

Maria began to make her presence felt in Arnold's professional life as well, commenting on his film scripts, attending meetings, making suggestions, criticizing those who worked with and for him. Arnold's other advisers tiptoed around her, not daring to risk riling her. They knew that the one thing they could never say was that they valued Maria's judgment less than her husband did.

"She is extremely smart and feels much more comfortable and happier to help me than to help herself," Arnold said five years after their marriage. "Reading movie scripts: 'You should talk to the director about this page.' 'I think you are wasting your time with this [scene].' Things like that. She is right there. When we have a rough-cut screening, the director will say, 'What are the things you didn't like.''' I'll say, 'I'm just seeing it the first time.' But my wife is handing him a two-page written list of comments."

Arnold's life was in place. He had the house he might well live in for the rest of his life and the wife who would live with him there. His career was equally set. It was not about grand artistic vision, but about marketing. His films were brilliantly conceived products on which he placed his mark from their very inception. "When people come to me with a script or concept, I tell them, 'Before we shoot the first frame, we have to shoot the poster,'" he told the Los Angeles Times. "What is the image.^ What are we trying to sell here.'' Say in one sentence what the movie is about. You can't.'' Then how are you going to sell the movie.'* So forget that. Next project."

Arnold's film that summer of 1986, Raw Deal, could easily be encapsulated in a single sentence: A disgraced FBI agent redeems himself as an undercover cop by single-handedly destroying a Chicago mob. The film systematically incorporated all the elements of a Schwarzenegger movie: the hero's brawn and wit, an unconsummated love affair, and a regular diet of violence, leading up to a banquet of death and gore. As Arnold's character dresses in black for that cathartic bloody buffet, he checks himself out in the mirror and then heads out to the music of the Rolling Stones' "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction," proving the song wrong by wiping out a Chicago mob. In ninety-seven minutes of film, he kills forty-two people.

Raw Deal failed at the box office that summer, as did its main competitor, Stallone's Cobra. As bad as the reviews were for Raw Deal, they were better

than those meted out to Cobra. Schwarzenegger beats slimy sly at his own GAME, headlined the Toronto Star. Stallone received brutal criticism for the mindless violence of his films, but Arnold was able to sidestep such judgments partially because his characters leavened their bloodshed with humor, but mostly because of Arnold's manipulation of the entertainment media.

Arnold had moved beyond the days when he reached out for every scrap of publicity, giving whatever outrageous quote would garner the most attention. He still did far more publicity than any other star of his magnitude. Now that he was established as a brand name, he and Parker rigorously controlled his message. He had no romantic illusions about the entertainment media being part of a glorious free press. He was his own product and he did not like others making money off him. He considered the media a poster on which to emblazon his message.

He was the product. If people were going to make money, sell magazines, and get ratings using this product, then he would exploit that product on his own terms. With the Weider publications, he had already been educated in controlling an image, but he was operating at a far higher level.

"There were many times we would be walking through a hotel and a gorgeous girl would come up and want a photo with him, and he wisely said no," recalled Joel Parker, partner with his wife, Charlotte, in a public relations firm. "There was a beauty queen from Russia and he said, 'Keep her away from me.' He's someone who understands the game at a very advanced level."

Arnold was so successful that he developed an almost proprietary attitude toward the media over the years. Journalists had their own professional hierarchy in which entertainment media stood in the lowest quadrant. Arnold had his hierarchy, too. At the top were the media and journalists who did what he wanted them to do, at the bottom those who did not.

Before the star talked to a magazine, Parker attempted to negotiate a guaranteed cover. She next met with the reporter and tried to understand him or her well enough to advise Arnold on how to handle the interview. In most cases, she limited the interview to a short session. That way, Arnold projected an aura of spontaneity as he rigorously monitored what he said. "Arnold is absolutely brilliant at how to project his own image while making the reporter feel very valued and important," said Parker.

What the star and the publicist were doing became common practice in the next few years among stars and their publicists, but Arnold and Parker were among the first to do it. The movie community is small, jealous, and

constantly observant of one another's prerogatives. His control of the entertainment media was as if Arnold had negotiated an extraordinary new clause in his contracts.

In exchange for access, entertainment journalists and media essentially gave up part of their freedom in an almost formalized way. Although most reporters easily went along, some of them blanched at what they thought were intolerable limits. Parker bore the brunt of whatever anger and dissatisfaction the journalist may have felt. "People were jealous of her position," said Arnold. "I always said to Charlotte, 'It's jealousy you have to earn. Obviously people think that you're good, and that's why they're upset.'"

Arnold grasped early on that he was not an actor like Dustin Hoffman or Robert De Niro who could achieve a long, successful career through the variety and quality of the roles he selected. He was the product, and if the public did not like him, he was finished. For the most part, the late-night and morning talk shows and much of the other entertainment media were places where an endless array of celebrity peddlers came forward to sell their wares. "I hate to do interviews and talk shows when I don't have a reason for it," Arnold said. "But when I have a film out, then I'm very excited, especially if I have a film I think is great."

When it came Arnold's turn to leave the green room to have his moment on television, he was professionally charming and witty, but never did he forget that he was out there to sell his film. He understood the rhythm of celebrity. He wanted to come crashing into the public consciousness like a great wave, then retreat until his next film, and then come crashing into awareness again. At times, he held back publicity if it wouldn't effectively promote what or when he wanted.

Arnold was obsessed with getting his face on magazine covers because his face was his visual signature. He could control his photographic image like no other aspect of his publicity. The words inside were decidedly secondary. In her office, Parker started tacking up each cover. That wall became a chronology of Arnold's career. On one side, there were almost exclusively bodybuilding magazines. Then movie magazines were added to the mix, and farther along business periodicals, and finally all sorts of general-interest magazines. Nothing just happened. As Arnold evolved, Parker went out and pushed publicity for each developing part of his career and life. He had grown to justify the words that had been written about him.

When he was out promoting a movie, he was not about to share a cover with Maria. It was not a competitive issue. He had a movie to sell, and the best way to do so was to have his focused image out there. Beyond that, he was his own story and it rankled him to be bundled up and trundled off into

another episode of the ongoing Kennedy saga. "I don't want them to sell the Kennedy shit," he said while he was a rising star.

As much as Arnold controlled his image, it was perhaps inevitable that he would at some point slip up. Arnold did almost no media without Parker prepping him—and usually sitting in on the interview. But one day Arnold agreed to an interview for Playboy with Joan Goodman, a well-regarded freelance writer, without first telling Parker.

Parker thought of Arnold as her media creation, and was infuriated that he would end-around her. "It was the one and only time that happened," recalled Parker. "I told Arnold, 'Don't do this.' I told him, 'I don't have a good feeling about this girl.' I was just so angry that she went around me and I was angry at everybody because of the fact that here I was, left with this big mess. I told Arnold how pissed I was."

Parker had always set the terms of the interview, but this time Arnold did it himself. "There's one condition under which I will do this interview," Arnold told Goodman, "that Brigitte Nielsen's name not be mentioned, even her initials. Nothing about her will appear."

"I can agree to this, and I will ask Playboy. But can you tell me why.''"

"Maria is not a difficult woman," Arnold said. "She's a Kennedy, and she understands the film business, but the one person who troubles her is Brigitte Nielsen."

Goodman flew to the set o{ Red Heat in Chicago. The subject of a Playboy interview usually sits with the interviewer so many hours that the celebrity inevitably says things he would not in a single session. During their first evening together with a group from the film, one of Arnold's friends alluded to Nielsen, and Arnold made a gesture as if relieved that the whole business was over.

During the many times Arnold talked to Goodman, he frequently discussed Nielsen—Stallone's ex-wife. As Goodman listened to Arnold's obsessive talk, she concluded that Arnold had been looking at the female version of himself. "She had ambition and ego equally to his and persistence in bettering herself socially, financially, in every way that was precisely the same," said Goodman. "Arnold was ambivalent about her, and it was quite raw."

Arnold explained how Nielsen pursued him, how he and Jake Bloom had gotten rid of her by setting her up with Stallone. Arnold happened to run into the newlyweds in a store in New York. "She said, 'Don't buy that jacket, it doesn't look good on you, let's go to another store,'" Arnold recalled. "She had everything under her control. I felt sorry for the poor guy."

Arnold savaged Stallone in his talks with Goodman, but he did so after asking

that his remarks be off the record. The first time Arnold talked about Stallone with Goodman was just before the trip to Chicago. He specifically said, "This is off the record." Later, while once again discussing Stallone, Arnold said, "This is not for the story," and Goodman said, "Of course."

When Arnold learned beforehand what would be appearing in the January 1988 interview, he realized he had made the largest media mistake of his career. It was not simply that Arnold said things that would dog him from then on but also that it was almost unprecedented for one star to unload on another the way he savaged Stallone.

Goodman claimed that the material Arnold declared off the record quoted word for word in the interview was repeated later on the record. If true, there is no evidence of it in the transcripts of the interviews. She also says that she and the Playboy lawyers decided that by "this is not for the story," Arnold meant merely that he considered it irrelevant and that if Arnold had wanted it off the record, he would have said so specifically.

"He [Stallone] is not my friend," Arnold said in the published interview. "He just hits me the wrong way. I make every effort that is humanly possible to be friendly to the guy, but he just gives off the wrong vibrations. Listen, he hired the best publicity agents in the world and they couldn't straighten out his act. There's nothing anyone can do out there to save his ass and his image." He went on to criticize Stallone's attitude toward women and even his dress, mocking his "white suit, trying to look slick and hip," and "that fucking fur coat when he directs."

Arnold was so upset that he called from Mexico, where he was on location, to talk to Barry Golson, one of the top Playboy editors. It was a call that should have been made by Parker, never by Arnold personally. "His beef was that he'd criticized Sly Stallone for his vanity in caustic terms and was now having second thoughts about it," recalled Golson. "Would I consent to delete those remarks.^ I asked why. He gave me a convoluted reason. I said I couldn't do that. He said he could offer me something much juicier at some future time. I said. No thanks. He then said that he would find some way of repaying me and Playboy for this lack of cooperation. Wound himself up into a real nasty snarl at the end."

Arnold had probably never given such a revealing interview in his life, and this man who learned from everything learned that he never again could fully trust a journalist. "Was what I said about Sly presumptuous.^" Arnold asked. "Yes, it was, because he was definitely a bigger star than I was. But I had my opinions about things, and I said it, but not for publication. She [Goodman] gives journalists a bad name, because I lost my trust in people.

"I was, at that point, still naive. And the sad story is that because there are some journalists who do not keep their promises, very rarely is there an interview where anyone says anything that is really on their mind. It's too bad, because the people never really get to know the real you."

As soon as the edition appeared on the newsstands, Arnold went on Good Morning America and explained that he had been misquoted. That was not true. He had been fairly and accurately quoted. Playboy replied that there were quotes that it did not use that were far more explosive. That was not true, either. Playboy had used the essence of almost all the off-the-record quotes in the published interview. And the German issue of the magazine published the off-the-record material about Nielsen. In the end, as Arnold realized, "what it created was him [Stallone] hating me and him feeling suspicious about me."

A few days after the Playboy issue appeared, British celebrity journalist Wendy Leigh says that Stallone invited her to the set o{ Rambo III in Yuma, Arizona. After no more than half an hour discussing his film, Stallone turned angrily to a discussion of Arnold. "We were sitting on these high chairs on the edge of the set, waiting for his call," Leigh recalled, "when he said, 'Arnold is a very bad guy.'" Once Stallone began, unmitigated rage poured out of him. "I never did anything to the f—er," Stallone said. "But he's always been out to get me. Now he's gone too far."

Stallone's best source for information on Arnold was his own ex-wife. "He had an affair with Brigitte," Stallone told Leigh. "She was in Austria with him, met his mother, found out a lot about him. I could give you a great story." Stallone said that Arnold's father had been a member of the Nazi Party. Arnold had even shown Brigitte Nielsen a picture of his father in a brown uniform of the Nazi SA.

Leigh says that over the next few weeks, Stallone told her a number of startling revelations. On February 19, 1988, she had a tape-recorded telephone conversation with the actor and told him that a story would be appearing on the front page of the British tabloid News of the Worid the following Sunday. Leigh also called Parker to tell her about some of the allegations. The publicist says she told Leigh that she was the child of Austrian Holocaust survivors, and if Arnold was in any way anti-Semitic or pro-Nazi, she would not be working for him.

The article headlined Hollywood star's nazi secret charged that Arnold was a "secret admirer of Adolph Hitler" who held "fervent Nazi and anti-Semitic views." The article alleged further that Arnold's father was not simply a Nazi but had personally directed the rounding up of Jews to be taken to

concentration camps. Nowhere in the piece was there a word of Pari^^er's denial of the charges. Leigh was given a joint byline on the story, though since she was living in America, she had nothing to do with writing it.

Arnold shrugged off bad reviews, but nothing was capable of angering him more than allegations that he was anti-Semitic or pro-Nazi. He immediately contacted Rupert Murdoch, the owner of A^^^^ of the World, to complain. In an attempt to back up the story, Leigh got in touch again with Stallone, who according to Leigh provided her with even more scandalous material on Arnold that had nothing to do with the original story. When she told Stallone that she was thinking of expanding the material into a book, he immediately came to her hotel to persuade her to go ahead. "I'll get you an agent, an accountant, a publicist, twenty-four-hour-a-day bodyguards," she recalled him saying. "Anything you want."

Leigh went ahead with the book. Behind the scenes, she claims, Stallone orchestrated much of the project. He found her an agent and put her in touch with Arnold's former publicist Paul Bloch. He lined up three other sources to attest that Arnold had an affair with Nielsen. He put the journalist in contact with Lacy H. Rich Jr., a gay aficionado of the bodybuilding world obsessed with hurting Arnold, and he became Leigh's crucial guide and confidant. Stallone also put Leigh in touch with a detective who led her to one of Arnold's former girlfriends. The star was obsessed with Arnold. "I think of Schwarzenegger every night before I go to sleep," Leigh recalled Stallone telling her.

Unauthorized biographers often receive their most revealing material from ex's and enemies. After the interviews, the author is left with the unenviable task of separating elements of the truth from the venom, vitriol, and willful exaggeration with which the material is frequently presented. Stallone was a fine source, but Leigh allowed him to become so close to her project that he even read the first draft of her manuscript. "Honey, reading this is better than getting four blow jobs," she remembered him telling her. The star had reason to feel that he would have his revenge with publication of the book.

Leigh was already in the midst of an expensive lawsuit, and she was playing a very dangerous game. Both Arnold's agent and publicist at the time say they knew nothing about Stallone's involvement, and Arnold probably did not yet realize the extent to which the hero o'i Rocky was responsible for the most offensive libels. He set out on several fronts to attempt to squelch the publication of the book, and when that failed, to bury it.

Leigh says that Arnold filed his lawsuit against the tabloid and her personally only after he learned about her book project. British libel laws are much tougher than in America. The newspaper had to prove not only that it be-

lieved the story' was the truth but that it was indeed the truth and in the public interest that the truth be known. In December 1989 the British paper settled with Arnold for an undisclosed sum and publicly stated that there was no truth to any of the allegations and that they would not be repeated. The lawsuit against Leigh continued. The journalist was left in an unenviable position. Her publisher was not about to publish a book by a biographer whose primary credential was that she had libeled the subject. She was forced to defend herself when it would have been far easier to join with News of the World in a public mea culpa.

When Leigh's book was in production at Congdon & Weed, publisher Harvey Plotnick received two unusual phone calls. "Both were people I know and who know Schwarzenegger," said Plotnick. "We publish a lot of sports and bodybuilding books, so we know a lot of people in common. One call suggested that if I didn't publish the book and paid Wendy off, then this individual and Schwarzenegger would in return write a joint autobiography. I was also told Arnold Schwarzenegger had deep pockets and could put me out of business." The second call offered to pay Plotnick for buying the book but not publishing it.

In the spring of 1990, Plotnick went ahead with publication o{ Arnold: An Unauthorized Biography. Parker called television programs that had booked Leigh or were contemplating it. The publicist pointed out that Arnold was suing Leigh for libel. She suggested that if the author appeared, Arnold would bypass the program on his next publicity junket. Several programs dropped Leigh or stopped considering booking her. Time's James Willwerth received what he called "urgent, demanding pleas" from Parker that he not mention Leigh's book in a profile on Arnold he was writing for the newsweekly. At the 1990 Cannes Film Festival, Parker asked reporters to sign an agreement that they would not ask Arnold questions about the book before they were admitted to a press conference. Stallone kept up the appearance of friendship with Arnold, even dancing with him at a party at the film festival that year.

In the end, Leigh was left not with a controversial bestseller but disappointing sales, heavy research expenses, a spurned media campaign, and an expensive lawsuit. Leigh says that she saw Stallone again on July 17, 1991, shortly before she gave a deposition in which she would be forced to admit that Stallone was the source for her charges about Arnold and Nazism. This was a few weeks before Stallone planned to announce that he had become associated with Arnold in Planet Hollywood, a theme restaurant chain. The partners were planning to hype the concept to a fever pitch and then go public. Arnold, Stallone, and Bruce Willis, the other star investor, were suppos-

edly buddies who loved hanging out together—so why not at their own theme restaurant? It would be disastrous if Stallone's role in the News of the World story became public.

Leigh says that Stallone introduced her to a high-powered Washington attorney and offered to pay all further costs of her lawsuit as long as his man took over. The attorney guided the case in such a manner that Stallone's role never came out. In 1993 she settled out of court by paying Arnold substantial damages and legal costs, all of which Leigh says were paid by Stallone. She also publicly stated that there "was not a word of truth" in the article.

During the course of the lawsuit, Arnold learned that Stallone was supporting Leigh, and he realized that the whole train of deception, starting with News of the World, had been started by his fellow star. The slanderous assertion that he was pro-Nazi and anti-Semitic would haunt him for the rest of his days in public life, and he had every reason to hate Stallone. When asked about the matter for this book, Arnold only reluctantly confirmed the story.

"I felt somewhat responsible because I said the things about him, and therefore it made him so angry about it," said Arnold. "If she [Goodman] would have kept her word, this would have never been in the magazine. He was so furious, because he obviously was a sensitive guy, and so with the Planet Hollywood thing, luckily we could just literally go and make peace."

Arnold did not so much make peace as establish a truce. He embraced Stallone when the cameras were on, but he kept a wary, watchful distance from the man who had once been his greatest competitor.

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

"You Are What You Do"

Arnold and Stallone were natural competitors, many of their roles almost interchangeable. After Stallone starred in Rocky IV in 1985, Holh^'ood joked that he would have to fight an alien in Rocky V. That sounded like a splendid idea to screenwriters Jim and John Thomas, who wrote a script in which a creature from outer space arrives in the Central American jungle. The enormous reptilian biomechanoid has a moral sensitivity unknown to most earthbound villains. He wants to fight and destroy only an opponent of worthy stature. Once the script was purchased by Fox and given to Commando producer Joel Silver, that opponent turned out to be Arnold, not Stallone. Arnold did not like the idea of facing off against the monster alone for the whole length of the film, and he had the scriptwriters add a team of tough mercenaries, including Jesse V'entura, a professional wrestler and former Navy SEAL, and Carl Weathers, who had so convincingly played Apollo Creed in the Rocky films.

Most of Predator was shot in the jungles of Mexico, and it was Arnold's toughest filmmaking experience since Conan the Barbarian. There was 100-degree heat, then nearly freezing weather. Arnold stood baked in mud or stripped to his waist. Arnold not only refused to complain but was a singularly upbeat force on the set. Critics who tended to like action films generally praised Predator, while others panned it. The film opened in June 1987 to major box-office success, in the end doing about $70 million worth of business in the United States alone.

Arnold's second movie that year was The Running Man, based very loosely on a novel by Stephen King writing as Richard Bachman. The futuristic thriller, which grossed $38.1 million domestically, takes place in a totalitarian

198 Fantastic

future akin to Orwell's 1984. Every night, the subdued masses watch the world's most popular television program, The RunningMati, in which criminals are chased down and killed by gladiators. The homeless watch the live, three-hour program on gigantic outdoor screens and bet on the outcome. This perverse game show is hosted by the egomaniacal, manipulative Damon Killian, played by Richard Dawson, the longtime host of TV's Family Feud, ratcheting up his own persona into a darkly brilliant performance.

The Dawson character throws a media bread and circus to the masses, a bloody, brutal game that the vast audience applauds and celebrates. They feel cheated when Ben Richards (Arnold) kills their heroes. Subzero (Toru Tanaka) and Buzzsaw (Gus Rethwisch), and again when he refuses to give them their expected denouement by killing a helpless third gladiator. Dynamo (Erland van Lidth). "Do it!" the audience screams. They want only victors. In the end, they applaud Richards's victory not because he represents freedom but because he is the winner.

The Running Man may be only a comic strip, but behind even the most politically denatured film about totalitarianism lies the Holocaust. In some of the early scenes Arnold is in a prison much like a Nazi concentration camp. During the filming, Arnold became friendly with George Linder, the copro-ducer. Linder introduced Arnold to his father, Bert Linder, who lost his wife and child but survived Auschwitz, Nordhausen-Dora, and Bergen-Belsen.

During the seven weeks Arnold spent on location at the Kaiser Steel Mill in Fontana, California, he had plenty of time for his friends. Linder, who was with him most of the time, says that he saw absolutely nothing of the untoward sexual conduct that would later be so well publicized.

Sven Thorsen had a role as the game-show host's massive bodyguard. During the shooting, Thorsen accompanied Arnold when he went shopping for a Porsche. "Arnold, give me a fucking break," Thorsen said after about the tenth trip.

"It's a thing you don't understand," Arnold said. "I want to stay hungry. I want to work to find the right car so I can deserve the car."

And so the two friends kept right on shopping. "We had seen forty fucking cars before he found his Porsche," recalled Thorsen. "He saved eight hundred bucks, and he was happy."

In June 1988 Thorsen was over at Arnold's house when he saw his friend sitting with a tear running down his cheek. He was holding an issue of Variety in his hands. Thorsen had seen his friend like this only once before. That was

when fifty-four-year-old stunt coordinator Bennie Dobbins had died of a heart attack during production. "What the fuck is wrong?" Thorsen asked urgently.

"Fucking Red Heat,'' Arnold said. In his just-released movie, he plays a Russian homicide detective searching for a dangerous drug dealer in Chicago with a local cop (Jim Belushi). The early scenes shot in the Soviet Union were both cinematically powerful and unique footage, but once Moscow detective Ivan Danko arrives in the Midwest, as The Washington Post noted, "even though the Austrian-born star adopts a Russian accent for the role, the character is virtually indistinguishable from any other he has played." Audiences realized that they had seen all this before, and the film earned only $35 million in the United States, a disappointing total for a man set on becoming the number one star in the world.

"Come on." Sven said, realizing that his friend was down. "It's number two. Come on."

"You don't understand," Arnold said, shaking his head. "I want to be number one."

By any measure, Arnold was a major star, but he did not receive respect and recognition as an important actor. He was merely a moneymaker. He had done so for 20th Century-Fox, starring in two of the studio's hits. Commando (1985) and Predator {\^%1).

In December 1988, Arnold attended an elaborate parry' on the Fox lot after the premiere of Working Girl, starring Harrison Ford, Sigourney Weaver, and Melanie Griffith. The film directed by Mike Nichols was the kind of classy project that studios lived for. Studio head Barry Diller followed the Hollywood axiom that nothing impresses like excess. The "Christmas in New York in Los Angeles" theme parry- included ice skaters on real ice, roasting chestnuts, enough gourmet food for much of West L.A., elaborate entertainment, and decorations all along New York Street.

Arnold was impressed. "Hey, Barry," he called out. "Barry!" Diller walked over to Arnold. "Barry," Arnold said as he grasped Diller's hands and embraced him. "Why don't you give me one of these premieres.'^" Diller looked up at Arnold and, as he turned to walk away, made a passing aside: "Thanks to you, I can afford to give this one."

Arnold realized that in HolK"\vood you are only as good as your last movie. If it was a bomb, then so were you. He was consumed with starring in hit after hit until he, too, had his spectacular premieres.

After the disappointing box office o{ Red Heat, Arnold went on a tear, starring in three enormous hits in a row that propelled him to the top rank of stardom and made him more than $50 million. For the first of them. Twins (1988),

the comedic director Ivan Reitman proposed to Arnold and Danny DeVito that they do a film together in which they would take small salaries but get a cut of the gross. The percentage that the two stars and the director took meant that for Universal Pictures to make a profit, Twins had to be an enormous hit. "The risk to the studio was tremendous," said Lou Pitt. "Here these three stars came together and said, 'Look, let's not take any cash, let's just take first-dollar gross together. We're all at risk but we'll keep the budget at a very low level, and if it works, we'll all get rich together, which is what happened."

As always, Thorsen had a small role in his friend's film. Afterward Arnold happened to be at Thorsen's cottage in Santa Monica on the very day he received a residual check for Twins. "Look at it, fifteen thousand dollars," Thorsen said excitedly, holding out the check to Arnold. "Thank you, Arnold. Thank you very' much."

"Good for you," Arnold replied. "You know I never see my residual checks, and I don't recall just what I got from Twins, if it was fourteen or fifteen million."

Arnold received 17^2 percent of the $110 million gross, or more than $20 million, at the time possibly the most money a star had ever made on a film. He also got his cut of the $104.7 million it made internationally. Within months other stars, from Jack Nicholson to Harrison Ford to Bill Murray, were cutting their own deals for a percentage of the gross, wresting money and power from the studios.

Twins was a breakthrough for Arnold in another sense, too. Arnold appeared for the first time in a comedy. He was the king of one-liners, but it was a daring stretch to build an entire movie around that part of him. Arnold played Julius Benedict, the result of a scientific experiment trying to breed the perfect human, blending the sperm of half a dozen brilliant men with a gorgeous young woman. The experiment went wrong when the mother had a second birth: a repository of genetic garbage, the bad, inferior Vincent Benedict (Danny DeVito). The audience was forgiving of a film that had far fewer laughs than an Arnold action film had killings, but Arnold carried it off perfectly as the sweet-tempered, gallant, virginal, innocent Julius.

The role resonated with something hidden within Arnold. When he was asked in August 2004 by NPR's Renee Montague what roles had most exposed parts of his own self, he turned first to Terminator, the Arnold archetype, then mentioned his character in Twins, "like a kid that's funny, humorous, and lighthearted and all that. I'm both sides." Maria chimed in that Arnold was precisely right. He had long protected that boyish, impish self, sheltering it from adult reality, and finally in Twins he could expose it publicly.

Arnold had an eye focused on what he wanted and the most grasping of reaches. For years he had known about a screenplay called Total Recall by Ronald Shusett and Dan O'Bannon, best known for their work on Alien (1979). The story, based on a classic science-fiction short story by Philip K. Dick, takes place on that unguarded border between reality and fantasy, truth and paranoia. A construction worker in 2084 is so obsessed with Mars that he takes a so-called fantasy vacation to the distant planet. To do so, false memories are implanted into his brain so that he can travel without ever leaving Earth. Something goes terribly wrong, and he becomes lost in a world where he does not know what is real and what is fantasy. In the screenplay, he ends up traveling to Mars, where he frees the darkly totalitarian society from its oppressors. Or does he.^ Is it all just a dream.^ For years, the unfinished screenplay wandered from studio to studio, lost in the endless circles of development purgatory.

Shusett, who was locked into the project not only as writer but as producer, was consumed by the screenplay that had monopolized almost a decade of his life. He was acutely sensitive to anyone who might wrest even a modicum of control from him. In the mid-1980s, when Dino De Laurentiis owned the project, Arnold approached the Italian producer about starring in the film. Dino wanted to consider Arnold, but Shusett thought him so inappropriate that he initially avoided him, not even returning his phone calls. When the two finally met in a Santa Monica restaurant, the writer was startled at the insight Arnold had into his beloved screenplay and how he would play the role.

"If I'm going to do it, you've got to change certain things," Arnold said. "Some of this dialogue is wonderful, but English isn't my first language. You've got to make my speech less complicated. The people around me can say sophisticated, complex things, but my part has to be simpler. I don't want the audience to say, 'Here comes this big Austrian again.' I'm a presence, a persona, not an actor, but I'll make it a big hit. But you gotta play it differently. It's like after twenty minutes, when does Arnold go into the phone booth and become Superman.^"

Shusett reluctantly conceded that Arnold might work, even if it turned the movie into more of a comic book. Arnold was not yet bankable on the big-budget level of this film, and Dino apparently was willing neither to pay the star his princely fee nor to give Arnold the control over the project that he considered only his due. After several false starts, De Laurentiis settled upon the latest sex sensation, Patrick Swayze, fresh from the hit Dirty Dancing, to be directed by Bruce Beresford.

In 1987 the film was in pre-production in Australia when De Laurentiis's company bottomed out. Arnold saw this as his opportunity, but he had to

move quickly before Dino's company declared bankruptcy. Arnold called one of the big new players in the industry; Andrew Vajna of Carolco, and suggested that he buy the rights to Total Recall. Each time the project had changed hands, it carried new production and screenplay costs until it now carried a monumental price tag of about $7 million. Arnold, the real estate tycoon, knew that the best time to buy a property is when there is a scent of desperation in the air. "[Bleep] him," Arnold said. "He's lucky if he gets half of it." Dino settled for about $3 million.

By then, Arnold had become a big star. His agent and lawyer cut a $10 million deal, plus a cut of the profits, in which the star also had veto power over the producer, director, screenplay, costars, and promotion. A few other top stars negotiated similar clauses, but none of them used that power as thoroughly as Arnold did or was so involved in evers' aspect of a movie. Despite whatever names rolled across the screen, Arnold was the ultimate producer, and he did not have to thump on his chest to get his way.

Even as he was getting Carolco to buy the script, Arnold already had Paul Verhoeven in mind as director. A few months before, he had run into the Dutch director at Orlando Orsini's, a popular hangout for movie types near 20th Century-Fox. Verhoeven had directed the edgy, daring RoboCop, and Arnold figured this dark poet of violence was the ideal candidate. Arnold personally called Verhoeven and importuned him to make Total Recall his next project, but what convinced the director was that it was "an audacious script," even if there were still some problems.

Verhoeven read all fort\'-two versions of the screenplay and realized that no one had come up with a decent third act yet. So he brought in his own writer, Gary Goldman. That was threatening to Shusett. If he invoked his practical veto power over the script, Verhoeven would walk—and that might be the end of Total Recall. It was almost unheard-of for a star to step into a project to protect a mere writer, but Arnold did just that. "Arnold just told them he wanted me involved," Shusett said later. During the eight months of shooting in Mexico City, the two screenwriters and the director bonded, and Arnold's instincts were vindicated. Early on, when Carolco criticized Verhoeven for shooting too slowK; Arnold weighed in again.

Arnold brought his own chef and food with him to Mexico. He was practically the only American who did not get sick. "I was completely dehydrated one night and had to be on fluids basically for hours to recuperate because I couldn't even stand anymore," recalled Verhoeven. "So, it was a tough time and shooting the movie, yeah, probably went slower than they would have wished, but I don't know how it could have been faster because it was so fucking difficult."

Total Recall Qo^x. about $73 million, then one of the most expensive films of all time. Much of the money went into elaborate sets and special effects in a film that has one startling action sequence after another. Arnold had respect for the creative contributions of everyone on this huge, complex project, and he did not impose his will arbitrarily or unnecessarily. If you happened to have walked onto the set during moments of levity, you might have assumed that Arnold was a boyishly nonchalant actor unconcerned with anything beyond his trailer and the camera. You would have had no idea that he was the central figure on Total Recall '\n every^ sense, missing nothing of consequence but asserting himself only on crucial matters.

Arnold was always under control even when he seemed not to be. For a man who considered impatience his worst weakness, he seemed almost casual on the set. His endless joshing, pinching of women, and bawdy humor were in part a means to loosen things up, to lance the inevitable tension of weeks on a set, and to create an atmosphere in which a film could be created to advance Arnold's fortunes.

\'erhoeven has a reputation as a brilliant, difficult man who makes few friends and leaves many enemies, and is devoid of false praise. He saw what Arnold was doing and ended up an unqualified admirer. "What impressed me was his abilirv' to always be aware of other people and to be really listening to them, always ready to say, 'Okay, what can be done then even if it's not possible, what can be done.^'" said the director. "How he would really bring people together. How we would sit together and say, 'Come on, guys, now let's go back to the beginning.' How he would handle the Mexican crew. And how he would be together in parties and in his speeches basically would bring people together, give them attention and embrace them in his kind of laconic and funny way. I mean, I've never seen that. So, basically for me, it was like, 'Wow, I wish I could do all that.""

Part of the very conduct that Verhoeven and his peers thought so positive and so bonding was precisely what irritated and offended others. On the set Arnold amused himself by teasing a stuntwoman about the peculiar tilt of her breasts and by goading another woman to drink so much tequila that she threw up. One day he went to the home of the famous sculptor Francisco Zuniga. Another guest recalled in an incident chronicled by Connie Bruck in The New Yorkerhow Arnold was seated next to a young woman who was dating the sculptor's son. "You know," he said as he touched the woman's arm, "the thing I love about Mexican women is how furr\' their pussies are." Such incidents were generally Arnold's schoolboy idea of fun, but in a world where an emerging political correctness sometimes trumped pleasure and spontaneity, Arnold was taking untoward risks with his reputation.

"There's certainly a mean-spirited part of Arnold, but that doesn't rule him in any way," said Pitt. The problem was, rather, that Arnold did not quite get the new rules of his adopted culture. "So whether he understands what pranks are palatable and acceptable and what aren't, he's clueless. His idea of saying something like 'girlie man,' which he used to use all the time, he thinks is cute."

Given the false memories in his brain, Arnold's character in Total Recall \% unable to know what is real. Nothing is real: not his marriage, not his life, nothing. He asks himself, "If I'm not me, who the hell am I.^" Total Recall has deeper emotional resonance than any of Arnold's previous films. His character had captured something truthful about contemporary life. With the relentless tempo of modern society and the endless intrusions of the media, like the character Quaid, we all ask ourselves, "Who the hell am I.^" Quaid has his answer in a scene where he meets Kuato (Marshall Bell), the mutant leader of the rebels. "You are what you do," Kuato tells him. "A man is defined by his actions, not his memory." If that is Quaid's mantra, so was it Arnold's.

In one scene, Quaid confronts the reality that he cannot remember Melina (Rachel Ticotin), the woman he loves, and has to tell her that for him their life together does not exist any longer. It is the most vulnerable moment Arnold had ever had in a film, confronting the theft of his entire emotional life. He found it extremely difficult to evoke his feelings for the camera. This was the part of an actor's life that he had always sidestepped, detoured to avoid territory he did not want to risk traversing. He was not in an acting class, but on a film set with scores of people watching him trying to emote what he could not.

He kept saying the lines over and over, but they had no life. He knew it and everyone else knew it, too. "I have to tell you something, Melina," he said for the umpteenth time. "I don't remember you ... I don't remember us ... I don't remember Verhoeven. I don't remember Shusett... I don't remember . . ." Everyone on the set convulsed in laughter.

After that, Arnold felt better, and the problem vanished.

One close friend says that he has discussed with Arnold the fact that Quaid is the film character he most closely resembles. He did not think of himself as an actor. He was playing bits and pieces of this colossal persona he had built. He had willed into creation a public image that was like a billboard hovering above the world. Was he playing himself, or was there no difference between the character on the screen, his own public persona, and whatever he was in his private moments.-* Like Quaid, Arnold was not pretending to be some-

thing different from what he was or thought he was. In the characters he played on-screen, he had not so much acted as projected parts of his own persona. On-screen at least he was a great, awe-inspiring wizard. But was that the real Arnold.'' Of course there was a difference between what he played onscreen and who he really was. But was he even capable of recognizing that difference any longer.'' He and Hollywood had created a giant mythic Arnold Schwarzenegger of such overwhelming force that at times even he did not know where the character ended and the man began.

Three weeks before Total Recall ^42:=, to be released in June 1990, Shusett handed Arnold a tape of a television news show in which Martin Grove, a veteran Hollywood reporter, said that Total Recall had a low 40 percent public recognition of the title. That was disastrous in a season of big-budget films, and while it was a nervy act to involve the star himself, it wasn't half as nervy as what Arnold did. After watching the clip, he went to Carolco and used his clout and their desire to work with him in the future to push the company to throw millions of dollars into new advertising. Hundreds of television ads began appearing across America, and there was almost universal awareness of Total Recall on the day it premiered. Total Recall was a blockbuster, grossing more than $119 million domestically and $142 million overseas, becoming one of the signature films of Arnold's career.

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

The Sins of the Father

Arnold's second 1990 film was the comedy Kindergarten Cop, directed by Ivan Reitman, who had also directed Twins. Arnold plays Detective John Kimble, who goes from the streets of downtown L.A. to undercover duty as a schoolteacher in the charming seaside tow^n of Astoria, Oregon. His task is to uncover the ex-wife of his nemesis, a vicious drug dealer and murderer. The first minutes in L.A. are brutal and bloody, an enjoyable romp through the familiar violent terrain of Arnold's most familiar screen persona. In Oregon we may be in a small town but these are not the streets of Frank Capra's America.

Beneath the sentimental veneer of the film, we are smack in the middle of dysfunctional, disoriented America of the nineties. Half the kids' parents seem to be divorced. One father abuses his son. Another has run off to live with his boyfriend. A mother is worried that her kindergartener may be gay. One little boy keeps uttering through the film, "Boys have a penis, girls have vaginas." And Kimble barges in on a couple of sixth-graders making out in an empty office.

This was the film you took your family to at Christmas in 1990, and Arnold made the film appear far more innocent than it is. He holds his own as an actor against the most merciless of scene-stealers, twenty-six absurdly cute kids. And he grows in vulnerability and humanity through the film.

I'his was a project in which Arnold and Reitman got big cuts of the gross, as with their previous collaboration. Kindergarten Cop grossed $91.5 million domestically and an astounding $110.5 million overseas for a comedy with very American themes. Arnold had done what no other action star had done before, transcended his own genre to become a worldwide star as a comedic actor.

Arnold may have had a special rapport with the children in Kindergarten Cop because in December 1989 Maria gave birth to their first daughter, Katherine Eunice. Arnold had long dreamed of a real family like Reg Park's, and his waiting all those years to marry did not make that dream any less important. If he was to do what Jim Lorimer said he must, to live life fully, then this was part of it.

He wanted to be there when Maria gave birth. "It's really great to be part of the delivery," he said afterward. "You really respect the woman more. The pain and the hours and hours of pure torture brought us even closer together."