2.

Mushrooms and toadstools

This is a book about fungi, a biological kingdom of equal status to the kingdoms of animals and plants, but one that has never attracted blockbuster television treatments accompanied by a full symphony orchestra. Many naturalists know little of the secrets of moulds, mushrooms, truffles and toadstools, and the membership of mycological fan clubs is a tiny fraction of those dedicated to birds (which we now know are just flying dinosaurs). I spent my professional life as a palaeontologist in the Natural History Museum in London, focusing on ancient, extinct animals like trilobites, but fungi have been my source of pleasure and perplexity for more than sixty years. Many people find them alien and threatening: the way so many toadstools appear so quickly and disappear with equal dispatch; their strange forms and colours; their reputation as poisoners. A Red Cage Fungus (Clathrus ruber) appearing on a flowerbed like a scarlet buckyball weirdly emerging from an egg can still astonish even the most blasé fungus lover. I find the strangeness of fungi is exactly what is exciting about them. The reference in my title to the movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind acknowledges this otherworldliness, and honours a third, great kingdom of life.

Calculations of how many species of fungi exist in the wild are always changing – and inexorably increasing. A well-argued 2022 estimate of three million species is double that made by the redoubtable British mycologist David Hawksworth in 1991, and it is not difficult to find still larger numbers. It is less controversial that only about 150,000 species have been named scientifically, so what remains to be discovered must be vastly more than what we know now. I have already spent several thousand words describing something of the natural history of just one or two boletes, which points up the impossibility of attempting to be comprehensive. Instead, I will focus on a selection of the larger fungi (macrofungi), the kind that might be spotted on a country walk. I delve later into a handful of microfungi that have particularly caught my attention. I make no pretence of a systematic trawl through the myriad different architectures that fungi have invented. I focus on just a few of those species that have made me think or wonder – my own Close Encounters – on a lifetime’s journey through a vast kingdom. Some science needs to be introduced, particularly where DNA sequencing has cast new light on old problems, but it is the unique charm of the mushrooms themselves that is centre stage. For those who are interested in field identifications, there is now a range of wonderful illustrated guides.[1] For those who get ‘hooked’, such books (and related online resources) take them further, but the sheer number of species can be intimidating, even to an experienced collector. The enumeration of species can become an obsession, rather like that of an extreme ‘twitcher’ preoccupied with adding to the list rather than the beauty of the bird. My intention is to explain the role that fungi play in nature, to illuminate some of their extraordinary adaptations, to celebrate fungal heroes and villains, and to recall special moments in woods and fields.

The distinction between mushrooms and toadstools is not at all scientific, but it could be described as traditional. Both are agarics – that is, fleshy fungi that release their spores from gills on the underside of the cap. Mushrooms are those agarics that can be welcomed on to the table – the edible favourites. Toadstools are agarics that cannot be eaten, in some cases because they are toxic or even deadly, but in many more cases because they do not taste good, or are too small to bother with. The distinction has nothing to do with scientific classification. On this criterion there can be mushrooms and toadstools in the same genus, with the frying pan as the terminological referee. To many readers the word ‘mushroom’ might well be synonymous with the cultivated variety (Agaricus bisporus) that occupies so much shelf space in the supermarket, possibly allowing the Field Mushroom (Agaricus campestris) as an honoured guest. The use of ‘mushroom’ more broadly for all edible species and ‘toadstool’ for the rest may be arbitrary, but it is a useful flag in the field; I do not guarantee perfect consistency. The mushroom family Agaricaceae is capable of a more formal definition, but then (for scientific reasons we will come across) will include things that do not look like mushrooms. The word originally derives from an ancient Greek root, so it could be said that agarics have a long pedigree. I met an Irishman in our woods using the word ‘garrets’ – same word, local variation. The boletes introduced at the beginning of this book have densely packed tubes where the agarics have their gills, and on many restaurant menus they, too, would be advertised as ‘wild mushrooms’. Boletus is another name that has come through from the classical era. I rather relish these antique roots (or should that be mycelia?).

Agarics and boletes present variations on a cap-and-stem construction that provides the best means of distributing minute spores to perpetuate their kind. Imagine if a primitive mushroom were like an open umbrella. This would allow the spore-bearing surface to be raised above the ground to reach the breeze. The underside of the umbrella would make a protected area for spore generation equal in span to the upper surface. By adding fine gills (lamellae) radially under the umbrella, the area of fertile, spore-bearing surfaces is multiplied under the same ‘cap’ – the mycologist Nicholas Money has estimated a twenty-fold increase. It is hardly surprising that this efficient system has evolved more than once. Another way of doing the same thing would be to create numerous tiny, spore-bearing tubes under the coverall: the Boletus option. This has also been repeatedly evolved. It might be said that the shape of a mushroom is almost a logical deduction.

Many other fungal designs will be encountered in this book, all of them dedicated to the same end – to cast their millions of spores upon the four winds. They can be brackets or puffballs, or ‘corals’ or crusts of any colour and texture, or inconspicuous spheres, or brightly coloured waxy cups. The most general description for this culmination of the life cycle is ‘fruit body’ – the sexual reproductive phase. The technical term for this is sporocarp, but I am attempting to keep such scientific labels to a minimum in general. However, I do add a few such terms in brackets for accuracy where it is appropriate. ‘Fruit body’ is a good description of what is, after all, the fruition of a life cycle. In some fungi it can last no more than a few hours. When it rains, tiny inkcaps (Coprinopsis) appear on my lawn shortly after dawn and are gone before the sun is high in the sky. Conversely, some hard brackets last for years; tough Ganoderma with an upper surface as hard as a tortoise shell appears at the base of living and dead trees, each season adding a new spore-bearing layer underneath. They are both accurately described as fruit bodies; their different life strategies are dedicated to furthering the same reproductive imperative.

Mushrooms and toadstools are the natural culmination of the food and energy accumulated by the mycelium – the hidden workhorse of every species. Fungi do not grow in the same way as plants that conjure their substance from sunlight and air. Fungi take advantage of the creative work of plants, either by consuming and recycling plant material (saprotrophs), or by entering into mutually beneficial partnerships with them. The basic building blocks of fungi are not blocks at all but tiny threads (hyphae) that are often less than a hundredth of a millimetre wide. These threads conduct nutrients and chemicals to where they are needed for growth. They actively seek out food most appropriate to the fungus, questing through wood or litter. Under the microscope, hyphae all look superficially rather similar, but they carry the instructions to make a Pin Mould or a Parasol Mushroom. Fruit bodies are constructed of hyphae, woven into tissues that can make a stout stem, or a colourful cap. They intertwine to buttress a gill, or spin precise cups or spheres to harbour spore production. They can even insinuate themselves between the tiny cells of trees and herbs, as ubiquitous as they are unseen.

Hyphae work together to construct mycelium, the fungal network that scavenges nutrients from the soil, and only appears when a mushroom is plucked carefully from the leaf litter as dangling white threads – apparently so feeble, yet so potent. Mycelium infiltrates soil as memory infuses consciousness. There are estimates of its abundance that leave you giddy: that if unravelled the mycelium associated with a single tree would stretch to the moon. When I was writing about the history of life, I always struggled to describe the meaning of four billion years of geological time. It was never satisfactory, because our minds are not geared to appreciate such numbers. It is equally difficult to imagine the living soil so minutely penetrated and enmeshed by living threads. On occasion, a damp log can look almost covered in a fog or shroud of pale fuzz where mycelium is most active, allowing us a brief image of its ubiquity. Merlin Sheldrake has done a brilliant service in explaining the networks generated by mycelium in his 2022 book Entangled Life, which rejoices in the interconnectedness of mycelial systems, and how collaboration governs success as mycelium fuses or spreads according to opportunities for nourishment. Possibly the most unusual aspect of the life of mycelium is what it means for the concept of a fungus individual. The fungal network fans out as it grows, but older parts can and do die out where nourishment is no longer available. Hence physically separate parts of the mycelium can take on a separate existence, and, migrating over time, may become widely removed from one another; but they are still the same individual (genet). Modern DNA identification techniques based on molecular sequencing offer proof of this identity. One fungus individual can be dispersed, but united in history. A split personality is the norm.

When I was young I enjoyed a series of dramatically illustrated books entitled ‘Ripley’s Believe it or Not!’ They featured lurid stories of the strange-but-true variety somewhat allied to the Guinness World Records books. I would harangue my parents with some gem from Ripley, such as ‘Did you know the venom from a bite of the Australian Fierce Snake can kill ten thousand mice?’ The best example of strange-but-true was yet to come, but how I would have relished announcing to my elders that the largest organism on Earth was a mushroom! No example better exemplifies the potential immortality of mycelium. In the forests of Oregon in north-west USA a single individual of the parasitic Honey Fungus Armillaria ostoyae spread from tree to tree to cover an area exceeding nine hundred hectares. Genome evidence proved it was indeed one organism. Deducing the weight of the mycelium was bound to be approximate, but there is general agreement that taken together it would outweigh a blue whale. It was the greatest! The fruit bodies would contribute an additional weight at the right time – clusters of yellow-capped, slightly scaly mushrooms, with pale gills and a rather tough stem carrying a ring near the top. As an inverse corollary, it could be argued that this is the organism with the lowest fertility in the world, because each of the hundreds (if not thousands) of mushrooms it includes sheds millions (if not billions) of spores, and this happens over very many years – more than two thousand if the original report is to be credited. If just one spore from each mushroom had germinated successfully and grown onwards, there would be no trees left anywhere on our planet.

A germinating spore releases a tiny hyphal thread that must ‘taste’ the environment to see if suitable nutrients are available. A saprotrophic species, for example, must land in appropriately moist leaf litter. The vast majority of spores will not survive the hit-or-miss of dispersal. When a spore does germinate in a favourable site, its hyphae must then assert themselves if there are species already established in the same area. It is tempting to invoke ‘nature red in tooth and spore’. And if that hurdle is passed the hyphae will branch and coalesce to set the mycelium off on its outward quest for nourishment.

Whether it is on a Petri dish in a laboratory or litter on the forest floor, the feeding threads will radiate outwards from the starting point, drawing a mycelium circle that in some agarics may take years to become yards across. When the circle is large enough and the conditions of temperature, rainfall and day length are just right, and a compatible mycelial partner is nearby, the network will organise to produce ‘buds’ (primordia) that will develop into fruit bodies. For large agarics the whole process rarely happens overnight, as is sometimes assumed, but once a mushroom starts to expand its stem (stipe) to lift the cap upwards it really does become the ideal subject for time-lapse photography. As the stem extends the cap opens out like an umbrella in a rainstorm: it is a synchronised performance. Since fungi are otherwise hard to photograph in motion, there are countless bravura performances available on the Internet of agarics arising in their reproductive glory. It is as if flaunting a hundred different kinds of parasols is the whole story rather than just the climax of countless questing explorations by tiny hyphal threads. The opening of the cap heralds the ripening and release of the spores in their millions – or rather, billions. A study on the Cultivated Mushroom suggested that more than 1.3 billion spores are released when a single fruit body matures. We are back to the problem of the age of the Earth: four mushrooms yield more spores than the years that have elapsed in the history of life. It is kind-of relevant but also kind-of absurd: nobody can really grasp what it means. Time outwits us, just as the fecundity of a single mushroom is a quantity beyond the grasp of a creature for whom three score and ten is both a lifespan and a calibration of reality.

When mushrooms develop they tend to fruit at the same time around the periphery of the mycelial web, producing a fairy ring. It is, perhaps, a prosaic explanation compared with the charming idea of wood sprites dancing in circles, but the rings are marvellous in their own way as a demonstration of the hidden life of agarics. Some saprotrophs like the Clouded Funnel (Clitocybe nebularis) are very often discovered in clearly marked circles in deep leaf litter. Rings of mushrooms can be found in grass as well as in woodland. In an open part of the New Forest I discovered one splendid example produced by a scarce species, Spotted Blewit (Lepista panaeolus), that was probably a hundred feet across, with several dozen fine mushrooms on display; it must have been decades in the making. The most obvious rings are produced in short turf by the common Fairy Ring Mushroom (or Champignon) (Marasmius oreades) – a modestly sized pale-buff agaric with a relatively long, thin and very tough stem, pale, widely spaced gills, and a smell of bitter almonds. This mushroom drives the keepers of bowling greens to distraction because it often kills a circle of grass as it advances, and paradoxically enriches the soil ahead, so its progress is marked by a brown circle outlined in deep viridian. Bowling greens are supposed to look like flawless carpets. Mowing machines and rabbits help to keep turf short and favour ring growth. Unlike rabbits, fairy rings cannot be discouraged from growing by the shaking of fists and the utterance of curses. The Fairy Ring Mushroom is an acceptable edible species – but only its cap – and once a fairy ring is identified the fruit bodies can be followed around the circle.

However, there is a poisonous toadstool that often grows in the same habitat, also in rings, also often off-white – the Fool’s Funnel (Clitocybe rivulosa). On one occasion I discovered the two different fungi with overlapping rings, so a careless picker might have made a serious mistake. The Fool’s Funnel has much more crowded gills and a shorter, softer stem, and the cap can be depressed in the centre, where the Marasmius often has a convex ‘knob’ in the middle. Trusting the differences does require a measure of self-confidence. Fairy rings also demonstrate how some parts of the mycelial web may die. Semicircles and arcs are commonly found in both grassland and woodland. You have to sketch in the rest of the ring in your imagination.

Mushroom or toadstool, after collection their identification follows a protocol that soon becomes second nature. The cap colour is the first thing to notice, but by no means the most important. Is it slimy or dry? The colour of the gills is at least as significant: white, black, brown, pinkish, in every shade. Fungi with nearly identical caps can have very different gills (their spores are usually the same colour), and vary greatly in stature. How are the gills attached to the stem? Do they run down it, or turn up towards it – or maybe they do not quite reach it? Does the stem have a ring upon it like a short skirt or a bracelet – or lack such a feature altogether? Does the flesh change colour if it is bruised, and is it tender or tough, or exude a bitter juice? Is there an odour? Is there a bulb or a bag at the base of the stem, and does it root down into the ground? A beginner can be surprised to see an experienced mycologist holding a tiny toadstool up to the light and sniffing it as if it were a fine glass of wine. It could be said that the identification of a mushroom employs every human sense except hearing, but that has not stopped me wishing that a particularly obscure species could tell me its name.

* * *

Fungi are so numerous and so diverse that there has to be some preliminary understanding of how the great kingdom is subdivided, if only to stop the reader becoming overwhelmed. Without a map nobody could find a way through the innumerable species out there. The question is: what map? There is now a vast quantity of data from molecular studies that have thrown up all manner of new insights into classification. Many such discoveries concern how families of fungi are constituted, and these tend to be of greatest interest to a dedicated specialist rather than a dilettante fungus lover like myself. Nonetheless, the essentials are important. We need a vocabulary as well as a map before we can make progress. Nineteenth-century mycologists had good microscopes and made many discoveries. Some of these pioneers were superb artists. Beatrix Potter was enamoured of fungi before she developed the animal characters that immortalised her. Potter’s fungal drawings are as exquisite as they are accurate; it is possible to make confident identifications from them even today. She mastered the microscope and observed spores in the process of germination. If the scientific establishment in the late nineteenth century had been more generous to the female sex, she might have been known for mycology rather than storytelling. Even more extraordinary were the brothers Tulasne, who must wait a while for an introduction. Before the beginning of the twentieth century, the broad patterns of fungal life had been delineated by a series of remarkable and prescient observers – more than I can do justice to. We have to begin there.

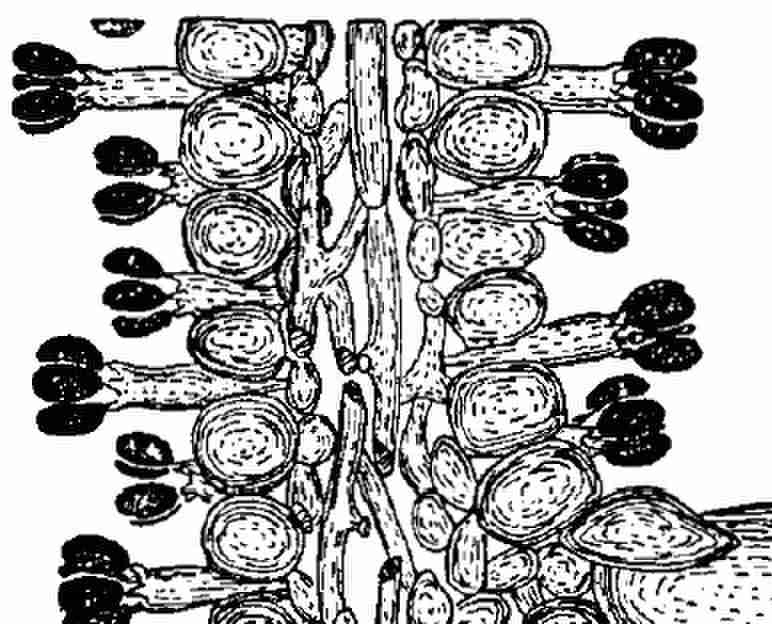

The larger fungi that are the focus of this book were soon divided into two great groups based on their reproductive structures observed at high magnification. All mushrooms and toadstools, boletes, puffballs and bracket fungi on trees are Basidiomycetes. The name is derived from the unifying feature of all these multifarious fungi – their spores are born on the apices of a special, sausage-shaped cell, the basidium. A section through a gill of a mushroom shows both sides lined with these cells, which are supported by hyphae forming a layer at the centre of the gill. The gills are there to support a fertile covering (hymenium) of basidia that are the factories for a vast output of spore production. Each basidium usually bears four spores like jewels on the edge of a crown. When they are mature, a special mechanism launches them into the space between the gills to be carried off in an air current. Professor Terence Ingold, who studied spore release in detail, described the basidium as ‘a spore gun of precise range’. You may prefer Nicholas Money’s comparison with Wile E. Coyote, the cartoon character who travels briefly horizontally into space before succumbing to the pull of gravity.

All this happens at a scale measured in thousandths of a millimetre (micron μm). The basidium of the Field Mushroom (Agaricus campestris) is about twenty microns long, and the spores it carries are about seven microns in length. Very few agarics have spores longer than 15 microns, and some are no larger than rod-like bacteria. In fungi with tubes rather than gills – boletes and many bracket fungi – the basidia line the sides of the tiny cylinders on the underside of the cap. There are some crust fungi and ‘corals’ that have neither gills nor tubes, and in these the basidia simply cover the fertile surfaces. The club-like corals are often little more than candelabras covered with spores waiting to be released. I shall refer to all these kinds of fungi simply as ‘basidios’ hereafter.

Basidia, each bearing four spores, lining the gills of Hairsfoor Inkcap (Coprinopis lagopus) as portrayed a century ago by Arthur Henry Reginald Buller.

The second great group of larger fungi is termed Ascomycetes, including morels and other cup fungi, woodwarts, Candlesnuff and many thousands of smaller and less conspicuous fungi. Their sexual spores develop in enclosed structures called asci rather than being released directly into the atmosphere, as in basidios. Asci are developed in a palisade – the fertile surface (hymenium) can line the inside of an open cup or disc, or be enclosed inside small flasks or spheres. Asci are generally elongate, sac-like and almost invariably include eight spores, which are much more varied in form, and often larger than, those carried on basidia. They can be thin threads or fat, spiky balls, or divided into compartments, black, brown or colourless, according to species.

When they are mature the spores are forcibly ejected from the asci, and puffed up into the air currents – hence their informal name ‘spore shooters’ (as opposed to ‘spore droppers’ – basidios). I have watched the process under the microscope, and it can be sudden and surprising. In nature, cup fungi will exhale a visible, hazy puff of spores into a passing breeze. The different ways asci release their spores is important in their scientific classification – some asci have neat ‘lids’ that open like hatches, others have double walls that change on maturity. I shall refer to this great clan simply as ‘ascos’ here, in line with ‘basidios’ – the ‘mycete’ parts of the formal names just indicate that they are fungi. I find two other informal terms useful in describing ascos, although neither is strictly employed scientifically today. ‘Discos’ are ascomycetes like cup fungi (Peziza) and morels (Morchella) where the hymenium is openly visible – as in the interior lining of a bowl-like fruit body, or the top surface of a tack-like one – and ‘pyrenos’ are those in which the hymenium is concealed inside a flask-like structure, usually blackened with melanic pigments (pyro indicates ‘burned’). Modern studies have revealed that these former categories have arisen several times from different ancestors – they remain useful here only as descriptive shorthand.

The division between ascos and basidios is an ancient one. Convincing fossils of ascos have been found remarkably well preserved in a Scottish silica deposit known as the Rhynie Chert, accompanied by other microfungi. This rock is of Devonian age (c. 410 million years old), taking us back close to the origin of terrestrial plants. The separation of basidios and ascos from a common ancestor is likely to have happened even further back in time. Some botanists suspect that fungi accompanied plants from water on to land, building towards the mutually beneficial collaboration between the two kingdoms that persists in their partnerships today. It is conceivable that plants would have failed to colonise the land without their fungal partners scavenging vital elements such as phosphorus. Not surprisingly, fossils of fungi are very rare, as they decay so quickly, but a perfectly recognisable inkcap has been discovered inside a specimen of Miocene amber (c. 16 million years ago). Spores are commoner, but often hard to match with those of living species. The earliest known basidio fossils are their distinctive feeding threads (hyphae) from beautifully preserved material contemporaneous with early coal deposits and about 330 million years old. For much of geological time, speculation has to take the place of facts.

A section of the spore-bearing surface lining the cup (apothecium) of the asco Neottiella rutilans showing the sac-like asci with eight spores, interspersed with long narrow sterile cells (paraphyses).

I must briefly visit another, controversial Devonian fossil, Prototaxites, that has been claimed as an asco and has attracted sensational headlines of the ‘When Fungi Ruled the World!’ variety. The ‘thing’ forms columnar structures that are mostly rather small, but can attain a height of more than eight metres, making it by far the largest terrestrial organism in the earlier part of the Devonian period, so the hype is not without foundation. Although Prototaxites was discovered in Canada in 1843, it long resisted definitive interpretation, but the fungus version seems to be carrying the day. The early land plants that lived alongside Prototaxites were low herbs, so it would indeed have towered above its photosynthesising neighbours, and surely must have lived for many years to achieve such a size, even though it is constructed only of tiny interwoven ‘hyphal’ strands. Surreal reconstructions of its living landscape show looming, pointed pillars overshadowing their lowly plant companions drenched in atmospheric ancient twilight. Some ascus-like structures have been found associated with the fossil, so the claim that it was a giant asco achieved wide currency, even though such long-lived, Brobdingnagian fungi are unknown among living members of this group.

Recalling that nearly all fungi rely on feeding on, or partnering with, photosynthesising plants, I find the size difference between plants and alleged fungus really problematic. If Prototaxites were feeding upon dead plant material it would be strange enough, but if it were a parasite that would be even stranger. There are no cat fleas bigger than the cat. If a mutually beneficial association had already been established, that is not so different from the relationship between porcini and chestnut trees in Borgo Val di Taro – but it does not make sense for the fungus to be bigger than the tree. I have only once had a close encounter with a fungus outsizing its partner. That was in western Newfoundland, where on very poor soil, and in the face of almost continuous strong winds, diminutive willow trees grew – you might say crawled – close to the ground, and on calm days in the fall their associated boletes actually ‘overtopped’ them. Special circumstances sometimes produce paradoxical results, but even in this case the fungus was nothing like eight times the height of its host. French mycologists seem to me to have put forward the most sensible explanation of Prototaxites. They claim it is comparable in structure to a lichen – that is, it is a collaboration between an asco fungus and a photosynthesising partner (possibly a blue-green ‘alga’) forming a living ‘skin’ that could grow through the seasons. Extant lichens can live for centuries, and their collaborative partnership makes them the toughest organisms on Earth. Prototaxites was not reliant on the plants it grew among and led its own strange life. Maybe this was ‘when giant lichens ruled the Earth’. These are not part of my story here.

Sketch by my colleague Paul Kenrick of the giant enigmatic Devonian Prototaxites, which has been claimed as a fungus. Note the small size of the herbs among which it grew.