12.

Morels and allies

In April the bluebells are at their best in the Chiltern Hills, carpeting the same areas under the trees that in autumn are scattered with mushrooms. The fresh, pale-green leaves of the beech unfurl at different rates: some are already clad in a cloudy garment of foliage; others have barely started to wake up. Sunlight streams on to the ground. It is quite different in late summer when the main mushroom season gets under way. Then the canopy cuts out most of the light and the brightest things on the forest floor are shining brittlegill fungi; in spring, everything is illuminated. Many of the ash trees may fail to unwrap their leaves altogether if they are succumbing to the onslaught of ash dieback. For a short while, the forest floor belongs to bluebells and lesser celandine. This is the time when an annual ritual takes place: the search for the most delicious of all fungi – the Yellow Morel (Morchella esculenta). It is a specialist for spring fruiting, on or around St George’s Day. It is also the object of a search when hopes run high, but disappointment is just as likely as success. The great morel hunt sharpens when rumour stokes expectation: a whisper from a colleague, perhaps, or maybe an online post. They are out there – somewhere.

Morels are saprotrophs, so they can be found in many different sites. I have had encounters with them along path sides, on mossy banks, or on the ground inside an old apple tree. They often turn up where you don’t expect them, and fail to turn up where you do expect them. They are only around for a few weeks, so delay is out of the question. There are traditions that suggest morels like old fire sites, prompting many a search, but I have never found them there. John Ramsbottom noted that morels appeared in abundance in France after the First World War in burned-out buildings. In April 2023 my nephew told me they were present on the north side of the South Downs in Sussex on the chalky slopes. A basket was immediately put in the car in the expectation of a good haul after an hour’s drive. The steep hills looked just right: a good covering of dog’s mercury, promising-looking patches of open chalky ground, scratchy scrub where we thought nobody else would have searched. Up and down we went, basket in hand. We poked under bushes, braved bramble patches and were mocked by magpies. Not a single morel was discovered – maybe my informant had scooped the lot. A few years earlier I had found a dozen of them near my home in an apparently identical site. They are as frustrating as they are desirable.

The morel is also a very distinctive fungus. It is sometimes described rather loosely as ‘a brain on a stalk’, but it is probably better compared with a rather coarse, spherical, yellow-brownish bath sponge carried on a white pillar. The cap is really an irregular array of small pits separated by prominent ridges, a folded surface designed to allow a generous area for spore release. Both cap and stem are hollow inside, and the flesh is rather brittle. The Yellow Morel is perhaps the most sought-after and elusive. There are other species, the commonest of which is the Black Morel, usually called M. elata, in which the cap is both darker, reflected in the common name, and elevated into a tall cone as the Latin tag might suggest. It is still undecided exactly how many different morels there are: a recent French review lists fourteen of the black ones alone. No matter, they are all equally edible. The Black Morel could almost be described as cultivatable. Yet again, the fashion for dressing flowerbeds with tree bark and woodchips as a weed suppressant has resulted in this species appearing more regularly as a pioneer coloniser of treated areas. We had our best-ever haul of Black Morels from our local supermarket! After the usual perfunctory building had been erected, the car park was laid out with a number of beds containing young trees to divide one rank of cars from another. Dark-coloured bark mulch was thrown down in some quantity. The following spring Black Morels were dotted around the car park. They looked like little black protruding pixie hats. I filled my largest collecting basket with them. I could not suppress a smug feeling from harvesting a valuable crop for nothing outside such a temple to consumption, full of plastic-wrapped food that had travelled halfway around the planet. I have seen Black Morels on mulched flowerbeds in new housing estates, though never in such quantity, and I have never felt comfortable with stealing from someone else’s garden. They only seem to have one year of glory. A different succession of fungi follows the next year; the morels must have moved on to the next new supermarket.

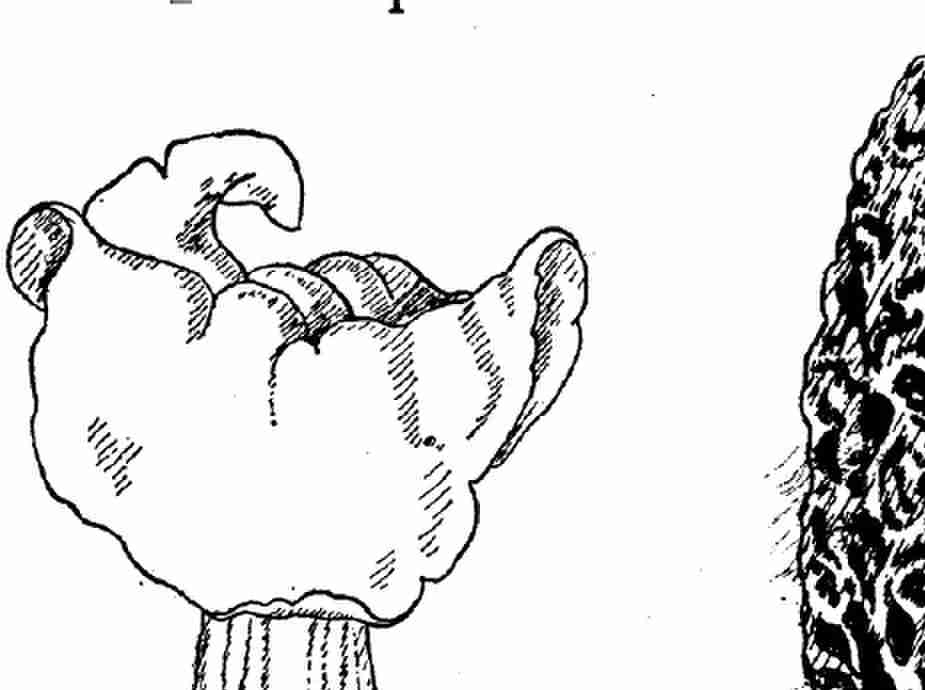

Morels are among the largest of the ascos. In the early days of mycology there was a concept of greater ‘perfection’ in fungi measured by the complexity of the fruit bodies.[1] On this measure Morchella lies at the top of the asco league, with such a well-developed stipe lifting the spore-bearing part above the ground, and with a complex cap atop, folded cleverly into small pockets. When the spore-bearing asci were discovered, they formed a palisade lining the depressions on the cap, and, when they were ready, spores would ‘puff’ into the breeze to aid their distribution. The White Saddle (Helvella crispa) had a comparable stipe, but the spore-bearing apparatus had but a few folds; it was one notch down from the morel. Such a hierarchical view of fungal complexity is thoroughly misleading in an evolutionary context, but it does resonate with the stature and complex shape of morels compared with their ‘simple’ cup-like disco relatives.

Where the morel can genuinely claim a top position is in flavour. This is a delicious blend of succulence and smokiness, completely different from the taste of the regular mushroom – perhaps that is not so surprising since agarics are such remote relatives of the ascos. Morels have been part of the gourmet’s wish list for centuries, which indicates that picking them has not greatly diminished the supply. By the time they have grown to full size they have already ejected many millions of spores, so picking them at this stage may not greatly affect their fecundity. They do like wet spring weather, and climate change could yet impact their abundance. They are certainly commoner in some regions than others. A friend of mine in New England sent me a picture every year showing his brimming baskets of morels gleaned from the apple orchards near his home. I have only seen such morel mountains in my dreams.

Morels and relatives: the White Saddle (Helvella crispa) (left) and one of the morels (Morchella) (right).

Caution demands that I mention a morel ‘lookalike’, the False Morel, Gyromitra esculenta. In general construction it is similar to Morchella, but the cap is more genuinely brain-like and convoluted, a tangle of thin lobes, and is a rich chestnut-brown colour. It seems to be particularly fond of growing under pine trees and in sandy soils. It is rather uncommon in Britain, but I was once brought a basket of them from Surrey by somebody who thought they had hit a morel bonanza. The reputation of False Morels for edibility is most confusing. In continental Europe they have been traditional and sought-after edible fungi, yet they have been associated with fatalities. The original describer, the great Dutch mycologist Christian Hendrik Persoon, gave it the specific name esculenta (‘edible’) in 1800, presumably because it was a familiar comestible in Europe. Cooking methods have varied: some recommend drying first, and all agree that the fungi should be blanched. The flesh of the False Morel does indeed include a notable poison called (unsurprisingly) gyromitrin, but its concentration seems to vary among different wild populations, and cooking helps destroy it.

Some people seem to be less vulnerable to its effects than others. In Poland, the country where the love of consuming fungi is unbridled, False Morels were responsible for a fifth of fungus fatalities in 1971. Several European countries have banned its sale, but not Finland, where it is a common species and a favourite food, and where many tonnes are consumed every year. However, it is a legal requirement that cooking instructions have to be displayed wherever the fungus is sold. The precautionary principle undoubtedly applies in this case: the False Morel is best avoided. Recent molecular evidence has proved that Gyromitra is not as closely related to the true morel as was once believed, so this is another example of ‘parallel evolution’ in fungi. Both probably evolved from fungi with simpler, ground-dwelling, cup-like fruit bodies having the asci lining the insides of the cups. Both fungi are solving a common problem: how to raise a fruit body cup off the ground to launch as many spores as possible into the air stream. Required: a stipe, and a way of folding the spore-bearing cup surface to get the maximum number of propagules into the smallest possible space. Result: a morel (or, alternatively, a False Morel).

Morels are only the most spectacular and complex of a very large group of ascos that have cup-like or discus-like fruit bodies. At the microscopic level the asci of many species release their spores by way of defined, terminal lids that open when they are mature. Many of them are very small, a few millimetres across or less, but their interest is greater than their size. They may be seen as white or yellow swarms on old nettle stems or fallen twigs, but their endless variety renders too many close encounters impractical here. I have saved a few for my account of the dung fungi I reared during the COVID lockdown (p. 257). The old term ‘discomycetes’ for these fungi no longer applies, as it is now known (thanks to DNA sequencing) that ascos with cup-like fruit bodies are derived from possibly as many as five different ancestral lines – but I still like the informal term ‘discos’ for species whose spore-producing surface is open to the air. It is simple and descriptive. Once you get to know them, a walk in the woods is transformed, because discos are everywhere in due season: on the petioles of leaves, inside acorn cupules or old hazelnuts, on the damp bases of ferns, on logs – and on lichens. The collaboration between discos and algae (and other photosynthesising organisms) that make lichens among the toughest living things on Earth is a great story, but it is not mine here, as I have always left the lichens to the lichenologists. At the Natural History Museum I worked alongside Peter James, the charming and self-effacing Prince of Lichens in the late twentieth century, and to try to learn lichens then would have been like picking up a violin next to Paganini.

The commonest large discos are saprotrophic cup fungi, usually found on the ground, that compete with mushrooms and toadstools for attention in the autumn, although many can be found all year round. Exceptionally, they can be as large as the palm of your hand. The simple cups of Peziza species can be any shade of yellow or brown, or even an alluring violet colour. One species is found very commonly on piles of rotting straw. The Blistered Cup (P. vesiculosa) is named from the appearance of the exterior, infertile part of the cup, which has an off-white, scurfy appearance, like unhealthy skin. It is one of the few fungi that can tolerate nitrogen-rich habitats, so the piles that farmers leave at the edge of the field are fruitful places to search, although staring closely at a gently steaming heap can attract odd looks from passing walkers.

My sister once found fawn-coloured disco cups dangling from her ceiling. They were growing happily in a corner from some damp wood that was decaying out of sight. Peziza domiciliana seems to favour our human dwellings (to judge from the scientific name), but presumably has somewhere it likes to grow in the wild. Unlike dry rot (p. 263), it is not invasive. Most other Pezizas are found on the ground, where they often last longer than agarics, but can be well disguised among fallen leaves of a similar colour. Ear fungi (Otidea) are rather more prominent forest floor discos, often clustered, in which one side of the cup is cleft, so they resemble what P.G. Wodehouse called the ‘shell-like’ ears of his young heroines. Small bouquets of the Hare’s Ear (Otidea onotica) seem to favour path sides in our woodlands, where their pinkish apricot colour could hardly fail to attract attention. This species is the best candidate to illustrate the release of ascospores. Kneeling down close to the cups, I exhale a careful puff of breath towards the open ‘ears’ – not as if blowing out a candle but more as if I were delivering a gentle breath to polish up a wine glass. If it is done correctly, and the fungus is sufficiently mature, a pale, wisp-like white smoke is ejected from the cup to vanish into the air. This is a cloud of many thousands of spores, and they disappear when they are dispersed into the slightest breeze. It is a good moment to invite my fellow forayers to imagine how the air we breathe is charged with countless emissaries dedicated to the survival of the species, invisible but omnipresent.

One of the most conspicuous and common discos is the Orange Peel Fungus (Aleuria aurantia), whose name exactly describes its appearance. It is usually found on rather bare ground, and its scattered fruit bodies look as if somebody peeling an orange had strewn small pieces of discarded peel over the soil. Decorating the path on a country stroll the bright patches immediately attract attention. Sometimes the fruit bodies are rather flat and distorted, or they can be relatively round and neat. It is one of many discos that have acquired red, orange or yellow pigments; these are invariably carotinoids, which help prevent cellular damage caused by sunlight. There are numerous tinier and less conspicuous discos,[2] but masses of the brilliant yellow Lemon Disco (Bisporella citrina) are readily visible in winter as bright splashes of colour decorating rotten wood, with little discs a few millimetres across swarming in their hundreds to make an obvious patch: beta-carotene provides the yellow paint of this common saprotroph.

Both Orange Peel Fungus and Lemon Disco have to vie for attention among a plethora of excitements from across the entire fungal kingdom on a typical autumn foray. At other times of year there is less competition, but more dedication is needed to bring home the mycological bacon. It requires a good pair of gloves and several layers of woollen clothing to poke among dead and damp willow branches lying in a swamp in February. I know several suitable localities in the Thames Valley. On one ornithological walk to identify winter visitors on the lakes near Twyford, I discovered piles of cut willow branches that had been left to decay. Willows grow promiscuously and every year the paths need tidying to keep them open for walkers. Cleared branches roughly piled in a damp corner offer exactly what is needed to encourage a winter specialist. The Scarlet Elf Cup (Sarcoscypha austriaca) looks almost like a tropical flower, absurdly out of place on a misty and chilly winter’s day. It is a large cup fungus that has its interior painted richly red; on this occasion half a dozen specimens were aligned along a decaying branch, almost as if they had been planted there deliberately. The strange thing is that only one branch was so favoured, and similar branches lying nearby carried no such bonus. The Scarlet Elf Cup is unquestionably one of the most beautiful of all the ascos, and its unexpectedness only adds to its glamour. A close colour match for the Scarlet Elf Cup appears later in the year on damp, decaying wood, however the Eyelash Cup (Scutellinia scutellata) is only a fraction of its size, although it occasionally occurs in sufficient numbers to become conspicuous. It does, however, bear a fringe of dark, graceful, spiky hairs around its rather flat disc, which, so far as it is possible for a fungus, makes it look somehow flirtatious.