13.

Things on sticks

If there is an autumn season favoured by agarics, and a vernal season favoured by discos, then there is a period in between when the Scarlet Elf Cup appears to be one of few fungal pleasures remaining. Soft fungal tissue – being largely water – generally cannot endure sub-zero temperatures. The first hard frost reduces most agarics to a sad pulp, a floppy relic of their former elegance. Even tough brackets stop shedding spores. There are a few survivors. The Winter Agaric (Flammulina velutipes) seems to be supplied with anti-freeze, having caps the size of large coins clustering on dead trees, their bright orange contrasting with darker, velvety stems. I have seen this fungus happily shedding spores while dusted with snow. Among other winter specialists, jelly fungi are curious basidios with fruit bodies that are frequently foliar or wrinkled, or make brain-like hemispheres, or maybe just pale blobs. When it rains or when the atmosphere is humid, they have a jelly-like texture that some people find repulsive. In this state they shed their big, sausage-shaped spores. When the sun comes out they dry away to practically nothing – no more than a papery wisp – but they can rehydrate perfectly in the next shower and shed their spores once again. Frost does not deter them either – they can freeze and thaw without ill-effect. Yellow Brain (Tremella mesenterica) is the most distinctive species because of its bright colour and folded form, somewhat like a banana-coloured slice of the cerebral cortex. After a gorse fire in the summer of 2017 in Southwold, Suffolk, the blackened stems were decorated all winter long with yellow jellies, hanging like frilly garters. The colourless members of these gelatinous fungi can be quite inconspicuous when clustered on twigs – my son suggested they looked like ‘bogies’, which was hardly flattering but was not a bad description. It has been proved that all these jellies are parasitic upon other fungi – which are often rather inconspicuous crusts. They are not closely related to another batch of winter jellies that are saprotrophs, including dark Witches’ Butter (Exidia glandulosa) that forms stumpy, black growths on fallen oak twigs. This is one example where the common names are ambiguous. You might think that butter (not brain) is more appropriate for Tremella mesenterica – after all, it is the right colour. Another sinister-looking black jelly is ‘Warlock’s Butter’ (Exidia nigricans), which forms contorted masses on dead beech branches in winter. A different naming question attends what is the most familiar of the jelly-textured saprotrophs – the Jelly Ear, Auricularia auricula-judae. This fungus really does look like a pinkish-brown ear, and usually grows communally on elder wood. When moist it is gelatinous and somewhat flabby, and when dry a crisp, in which state it can be stored indefinitely: to revive, just add water. Once rehydrated, it is perfectly edible, although some people don’t enjoy its gelatinous texture. The Chinese Cloud Ear Fungus is a close relative. In China in the 1980s I met it at the bottom of a bowl of clear chicken soup and was informed that it was ‘very good for old age’, and since I am now old I presume that it worked. The problem with the Jelly Ear is its species name in Latin, which obviously means ‘Jew’s Ear’ – an unacceptable name for reasons I do not have to explain. But there is a rule in scientific nomenclature that valid names cannot be changed, so there it will remain as a reflection of past attitudes; the name was already in use before the end of the eighteenth century.

Attempts to prolong the fungus ‘season’ into the winter months led me inexorably to study ‘pyrenos’. If you know where to look, fungi can be found along country lanes and by tracks through woodland even as early as February. Many of them show up at first glance as no more than black patches lurking on dead or dying tree trunks, or painting twigs or the stems of herbs. They could easily be passed by unnoticed, but once their fungal nature has been recognised they seem to be everywhere. They may cover the whole length of a fallen beech trunk – an entire tree wrapped up in a fungal sheet! The surface is rough to the touch and pimply, like the skin of a lychee. A casual glance might have suggested that the trunk had somehow been set alight, blackening the surface with a patina of carbon, but this is a living covering, a pioneer wood-rotting fungus that has covered itself in a funereal cloak, black as tar. Under a hand lens, the rough surface is revealed to be the result of thousands of tiny pyramidal warts, each one fluted delicately to a pointed tip. This Spiral Tarcrust (Eutypa spinosa) must be the largest, but least-noticed organism in the forest.

If the surface of the crust is cut with a sharp knife its secret is revealed. Below the warty exterior are a series of diminutive chambers, each one filled with a gooey substance. These little flasks (perithecia) contain a lining of many asci, every ascus including eight smooth, sausage-shaped spores. The gooey tissue is their nursery. The asci ripen in sequence, when they elongate into a channel in a corresponding wart above them, where their spores are ejected into the atmosphere. The spores are only about seven thousandths of a millimetre long. When the fungus has done its job of spreading its spores, the flasks remain behind, all hollow and empty, and they will endure in this state for months. This reproductive activity mostly happens during the wintertime, when you might imagine the whole forest is asleep. It is actually invisibly seething.

The vast number of spores produced from a single log defies computation, though doubtless the numbers of stars in galaxies would be a measure. The blackness of the fruit body explains why these fungi were called pyrenomycetes, from the Greek for ‘fire’ (as in pyromaniac), and the obvious difference from discos is that the asci ripen inside closed vessels rather than open to the air; but, like the discos, it is now well established that these flask-bearers include several groups that are only remotely related to one another.[1] It remains appropriate informally to continue to call them all pyrenos. They are united by black walls – a wrapping of black melanin, the complex polymer that protects from ultra-violet damage and resists just about everything, be it natural (or unnatural) acids or laboratory solvents. It stops living tissues drying out. Maggots cannot get to the soft bits. If you were of a sensitive mycelial disposition, you could not have a better covering.

Once I had started looking at pyrenos I found them everywhere, and not just in winter. In our wood I noticed that dead beech branches carried small, round, densely scattered dark-grey blisters dotted with spore-releasing apertures; they broke through the bark, peeling it delicately back around their perimeters – this was Beech Barkspot (Diatrype disciformis). Trunks of the same tree were decorated with swarms of what might have been undersized rusty-coloured strawberries, Beech Woodwart (Hypoxylon fragiforme). My hazel branches carried less knobbly spheres of a similar size and colour (H. fusca). I saw fallen, small branches belonging to broadleaved trees wholly blackened by a covering of Common Tarcrust (Diatrype stigma). Each dry nettle stem had lines at its base of tiny black flasks carrying prominent necks, which somebody with a sense of humour had named Nettle Rash (Leptosphaeria acuta). It became a routine on country walks during the winter months to carry a linen bag to pop in what my family referred to – sometimes with a hint of exasperation – as ‘things on sticks’. And indeed there proved to be a great many different things on sticks.

I was fortunate to have learned the British flora when I was still a schoolboy naturalist. I didn’t know the Latin names, but I did know the old English names like Garlic Mustard, Hogweed and Cow Parsley. There was no practical purpose to acquiring this catalogue of identities – it was just what young naturalists did at that time. Like many skills learned young, the old names stayed with me. They finally proved very useful to help with identifying things on sticks, as many of these fungi were confined to single hosts. A fat book by East Anglian naturalists Martin and Pam Ellis was organised by host plants (rather than fungal names) so if I identified the host I was well on my way to making an identification of some small black fruit body on a stick. I soon learned that some of these pyrenos fruited inside the stick – using the thin layer of bark as a protection – and only the small mouths (ostioles) of the spore-bearing flasks protruded through the bark to release the spores.

These fungi were more easily detected by touch than sight, and I found myself lightly stroking dead twigs, as might a blind man, to detect the tell-tale roughness produced by fungi that were ready to release their spores through small protruding mouths. I occasionally had to explain what I was doing to some perplexed dog walker. When I found a productive twig it went into the bag for further investigation. Things on sticks proved to be inexhaustibly varied.

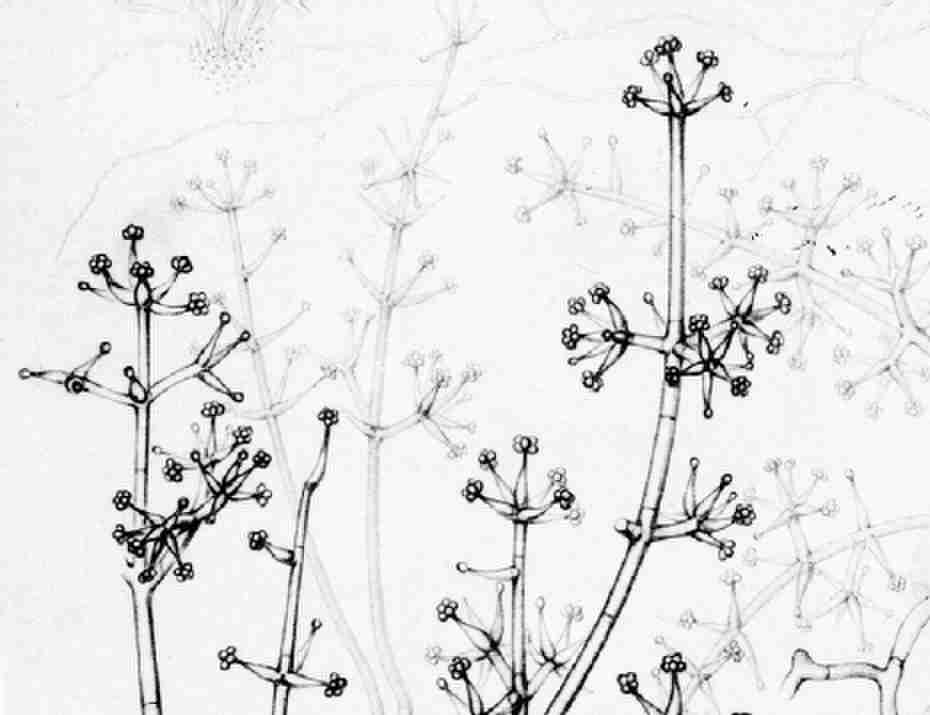

At this point one of the great books should take a bow. Many biologists know the work of Ernst Haeckel, whose images of organisms – particularly invertebrates – combine astounding accuracy with artistic delight. They have been reproduced countless times, and adorn the offices of many scientists who have never picked up a pencil in their lives. Very few biologists know the work of the Tulasne brothers, let alone have handled a copy of Selecta Fungorum Carpologia (1861–3). Yet their work on fungi combined advances in knowledge with astounding and beautiful drawings, one of which is reproduced here. They surely deserve to be more widely appreciated. Charles and Louis Tulasne died in Hyères in France within a few months of one another in 1884 and 1885 respectively. As appropriate for mycologists, they had a symbiotic relationship. Charles illustrated what Louis described, turning what could have been exercises in microscopy into art. So solid are Charles’s images that the viewer feels as if she could wander into these strange groves of monstrous flasks and waving threads, bombarded with spores of all shapes and sizes. A lesser artist would have illustrated the bare minimum to characterise a particular species, but Charles created vistas. His pyreno flasks bubbled over with asci. He drew at every scale from twig to spore. The word ‘surreal’ is rather overused to apply to anything a tad weird, but I do believe that some of the strange landscapes painted by such surrealist artists as Yves Tanguy are no more effectively realised than the fungal illustrations of Charles Tulasne.

One of the Tulasne brothers’ incomparable drawings for Selecta Fungorum Carpologia (1861–5), a mycological landmark that linked anamorphs bearing conidia with sexual fruit bodies bearing asci. This shows Trichoderma delicatula with finely branched structures carrying conidia on the left, and ascus stage the spheres to the right.

As for the science, the Tulasne brothers broke new ground that changed everything that was known before. They proved that fungi could exist in two forms, with apparently little that was obvious to connect them. As the subtitle to the 1931 English translation of their work put it rather pompously and not wholly accurately, they showed ‘those facts and illustrations which go to prove that various kinds of fruits and seeds are produced, either simultaneously or in succession, by the same fungus’. Many of the pyrenos they investigated were split personalities. The mature fungus embodied in its black phial full of asci was not the whole story. At another stage in its life cycle that same species could look completely different, and its spores were not necessarily enclosed in a receptacle. It might well be a white fuzz of hyphae decorated with spores like a Christmas tree with baubles, or maybe a minute pad dedicated to producing spores like a production line in a factory – or perhaps a black flask containing odd-looking spores that were not produced in asci. Some of these fungi might once have been called ‘moulds’, but now they were recognised as stages in the life of an asco. The spores produced by the alter ego growth stage were often different in shape and size from those of the ascus stage. Many of the details of this double life magnificently laid out by the Tulasne brothers have been proved time and again by the researchers who followed in their footsteps, and are now routinely tested by molecular evidence. Their newly characterised phase in the life of the fungus was later termed the ‘anamorph’ – which taken literally means ‘without shape’, but it would be better to say that they had a bewildering variety of different shapes. The spores produced by the anamorph are called ‘conidia’ to distinguish them from those produced inside asci.

The ascus-bearing fruit body is the sexual stage in the life cycle of the fungus (the teleomorph). The conidial stage is asexual. It provides a way of producing prodigious numbers of spores very rapidly when the going is good. Conidia, carried by the slightest breeze to a favourable site, may be able to germinate successfully almost immediately and start a new mycelium. They are mycological storm troopers. If the fungus in question is a pest, fields of crops might be devastated within days, courtesy of hordes of microscopic invaders. The ascus stage has been described in the past as the ‘perfect’ stage, which naturally makes the anamorphic stage ‘imperfect’, even though it is perfectly adapted for its function. Though many conidia-carrying fungi have now been linked with an ascus-bearing stage, there remain others that have not. Many of the details of the anamorph require microscopic examination, which takes them out of my purview here, but they have proved of great importance in identifying genera and species – and are often more reliable than the features of the ‘perfect’ stage alone. Many ascos pass most of their life as mycelium in the growing state.

This complex lifestyle may be a little hard to comprehend for a novice. The mycelium of the anamorph carries one set of chromosomes in their nuclei – in the usual terminology, it is haploid, as are the conidia that are produced in such profusion. The spores produced inside the asci during the sexual, diploid stage of the fungus are the product of complex ‘mating’ of two compatible haploid partners. Only once conjoined can the asci develop the spores that carry the future of the species into subsequent generations. Most asco species need to find and ‘marry’ a compatible mycelial mating type before they can complete their life cycle. There is no equivalent to male and female here (they are conventionally just represented by + and -). To parody a well-worn phrase from Star Trek: ‘It’s sex, Captain, but not as we know it.’ This is also the place to emphasise that a comparable mating ritual also applies to basidiomycetes before they can develop their diagnostic basidium on which the four spores are held like jewels on a coronet. Haploid mycelium must find a compatible partner before the fruit body can develop. The situation is more complicated in basidios because there are often more, and sometimes many more than two mating types – and not every pair is compatible.[2] The intricate particulars of these mating rituals have been studied in more than microscopic detail by the intellectual successors of the Tulasne brothers, but they have never been illustrated with such panache as in the original.

The different personae of ascos may seem a tad theoretical and hidden out of sight but they play out on the ground in dramatic fashion. When Jackie and I acquired our small piece of Chiltern woodland in 2011, we noticed a plethora of young ash trees. There were so many that we wondered whether we should thin them out before they overwhelmed the small beech trees that were competing for the same patch of light at the edge of the canopy. Ash is always the last woodland tree to unfurl its leaves in the spring, but then it makes up for lost time with prolific growth. When I wrote the story of our wood in The Wood for the Trees, passing reference was made to the appearance of ash dieback in the Chilterns. I had encountered the disease two years earlier when making a television programme about fungi. At that time dieback was found in Norfolk, but its potential for causing a major crisis for ash woodland had already been acknowledged. It was believed that it had been introduced from the Netherlands on infected saplings. The film crew and I had to splash through a footbath of disinfectant at the edge of the affected woodland to make sure we did not carry spores to a new site. It was already too late.

By 2021 we were accustomed to the sight of dead ash groves in the midst of our hills; straight trunks topped with twigs that all turn upwards towards their tips made them all too recognisable from afar. The National Trust was soon felling trees next to public footpaths, because those that have suffered dieback rot on the inside and suddenly drop. In our own woodland all the young trees were dead or dying – displaying typical outlines with the highest twigs and small branches carrying no more than a few blackened, dead leaves. They were becoming both leafless and lifeless. A few viable shoots struggled on nearer the ground. We need not have worried about them crowding out our young beech trees. We were now more worried about losing all our ashes. Larger ash trees are apparently more resistant, but will succumb in the end. Some of them are centuries old.

The pathogen that causes dieback was given the scientific name Chalara fraxinea as recently as 2006. For several years the agent responsible for ruining many a woodland was referred to as chalara in the press, usually accompanied by a picture showing the diamond-shaped lesions below small branches that were typical when the microfungus blocked the vital ‘plumbing’ of the young tree. Chalara was the anamorph of a lethal fungus; it was the asexual, rampant invader, and an invisible killer. When ash dieback is mentioned now in the media the reader (or listener) might be confused to see it named rather as Hymenoscyphus fraxineus. It is, of course, the same fungus as chalara! But the current name is its sexual stage – and this name carries the day. Hymenoscyphus is a genus of small, white discos with short stipes, and this is where the sexual, ‘perfect’ stage of ash dieback belongs. It is usually just a few millimetres across. I have found it on the petioles of the fallen leaves of ash trees, looking as if tiny, white tacks had been inserted in a line.[3] The ‘split personality’ of this invading asco was central to its rapid spread and subsequent survival: the chalara stage as aggressor, the disco stage to ensure survival of the species. Mighty trees have been brought down by something that is as small as a pinhead.

There is hope for the ash tree, in spite of its fungal foe. Dieback probably arrived on an imported exotic species of ash, and the European species offered no resistance to infection. It is now widespread across continental Europe and in the United Kingdom. When we were driving through France in 2023, the spindly skeletons of dead ash trees were a frequent sight along the autoroutes. But as we passed progressively upwards along the Isère valley towards the French Alps, it was noticeable that healthy looking ash trees were everywhere. They abounded on the steep slopes of the valley sides, where they were among the commonest of the deciduous trees. Maybe the long and cold winters of that region are not tolerated by Hymenoscyphus fraxineus and alpine habitats may offer a redoubt for these beautiful trees. A more domestic recovery might also prove possible. Ash trees are prolific seeders and among the many seedlings are a few that resist dieback. Natural selection will favour such trees; although it may take many years for this obduracy to feed back into the landscape, the ash will not be lost, and as I write human selection of resistant strains is speeding the process.

Sadly, the same cannot be said of Dutch elm disease. The fungus that administers the coup de grâce to the majestic elm is a tiny, flask-like pyreno called Ophiostoma. The lethal fungus spreads from tree to tree carried by a bark beetle – a weevil of the genus Scolytus – which carves out feeding galleries beneath the bark that make handsome traceries on bare trunks, until their lethal effect confounds admiration for their symmetry and execution. Once the disease is established, the conducting tissues of the tree become blocked, and the poor plant essentially starves to death, deprived of its photosynthetic nourishment. Its foliage yellows and then turns brown, as if scorched by an invisible flame. Dead trees can be seen in every other hedgerow in East Anglia where once fine, almost feathery crowns allowed John Constable a chance to display his mastery of portraying grand trees. Alas, poor Norwich! The trees do not die completely, because they regenerate clonally from suckers, but when these get to about twenty feet high the disease returns, so that affected hedgerows develop an unattractive mixture of dead standing wood and living shoots. The English elm very rarely sets seed, and its clonal reproduction means that it does not have the same potential as ash to produce immune strains.

Today, the only stands in England that Constable would recognise are around Brighton, seaward of the South Downs, which act as a barrier for the dispersal of the beetles. Vigilant local naturalists look for telltale signs in the foliage of these survivors that indicates when the barrier has been breached, and infected trees are immediately destroyed. There is historical evidence that ‘waves’ of Dutch elm destruction have happened in the past, and eventually trees do regenerate, but this is scant comfort for those who would love to see the stately trees rising above the ditches in eastern England. It is some consolation that the related wych elm does set abundant seed, allowing for more genetic variation, and resistant strains of this attractive tree are evolving to feed the many insects, especially moths, that rely on elms as part of their life cycle.