19.

Rotters

Lily, our Polish cleaner, brought the object to me in a waste paper basket. She had been working in a house along our street when she noticed an alien growth in the corner of one of the children’s bedrooms. The owners had been on holiday with their family for several weeks, and the thing had grown since her last visit. The house was immaculate, so a lurid, living carbuncle more than a foot across erupting from near the top of a white-painted room was not something that she could have failed to notice. It had grown with dispatch since her last visit. It had a soft texture, but coherent; almost gelatinous, yet hanging together. It somehow boded evil intent, but it was hard to say why. Lying in the basket, it was reminiscent of a dead jellyfish. Much of the object was orange-brown and roughly corrugated, oozing a few water droplets, but surrounded by a white fringe, as a gown is by selvedge. Lily had been able to peel it off from the wall using a broomstick. It had offered little resistance and was readily dislodged, falling into her improvised receptacle. I recognised it at once: it was the Dry Rot Fungus, Serpula lacrymans. ‘Lacrymans’ means ‘weeping’ – referring to the water droplets exuded during rapid growth of the fruit body – but it could equally refer to the emotions that are stirred in householders on discovering they are hosting an insatiable fungus; ‘odious, insidious, hideous, obnoxious, downright abominable’, as the American mycologist David Arora described it.

Dry Rot Fungus eats the wood used in buildings, spreading by means of mycelial cords that seek out new sources of food at astonishing speed once they are well established, passing over and even through inedible objects in pursuit of uninfected wood. Unchecked, it continues its relentless progress until the affected building falls into ruins. When the pest is discovered there is no choice but to remove all the infected timber – with a wide safety zone around it to eliminate any that may have been infiltrated by the invader but not yet shown symptoms. As my neighbour discovered, this can cost several thousand pounds. The fungus often produces its fruit body well away from the wood that is being plundered, as it needs to find an appropriate place to release its spores directly into the air. Its hyphae can pass through the pores in brickwork, to ooze out into bedrooms, as in my neighbour’s house, or even on to stored paraphernalia in attics, there to form the brown wrinkled surface from which the spores take flight. To add insult to wooden injury, it smells unpleasant and musty. The rusty stain of masses of spores often covers nearby surfaces, looking like spray paint.

Dry rot refers to the kind of attack made by several different wood-rotting fungi, even though Serpula lacrymans is the most dreaded culprit. It is also something of a misnomer because to get started this fungus requires damp conifer wood, where its spores can successfully germinate – a completely dry wooden building will not be infected. A temperature of just above 20 degrees Celsius promotes optimal growth, but the fungus tolerates colder conditions with aplomb. Once established, its mycelium breaks down wood in such a way that it releases water molecules, so then it becomes like an internal combustion engine capable of manufacturing its own fuel. It is free to race ahead without further impediment. Its hyphae pillage extra nutrients from plaster or brickwork to help it grow – oil in the engine, if you like. It is implacable. Fortunately, modern regulations are designed to ensure dry buildings, so the Dry Rot Fungus cannot get going. The majority of infestations are associated with Edwardian and Victorian buildings; our neighbour had a flat roof that was prone to collect water, covering a large Edwardian dwelling, so the slightest leak might have allowed a passing spore to find suitably moist timber.

‘Species jumping’ has been much bruited since the appearance of COVID-19 and other malevolent viruses. A virus species on bats – who often get the blame – vaults on to a human in a ‘live meat’ market, usually in China, and then proceeds to cause global mayhem. For the plot of a horror story one might toy with the idea that Serpula lacrymans could take a similar jump on to humankind. Such a scenario with regard to Cordyceps has already been mentioned. The grisly movie would show the mycelium plunging into the bowels and up the spinal chord, fuelled by the riches of a high-protein diet. Victims would stagger around making suitably agonised cries while the white-coated scientist declared herself baffled. The climax of the life cycle might be the slow-motion eruption of the fungus fruit body from the side of the head. Such fantasies are worth entertaining if only to point out why they are impossible. Serpula is not free to jump around the animal kingdom in a way that is frequent in viruses. It is a dedicated vegetarian specialist. Its feeding mechanisms are obligatorily linked to an ability to degrade cellulose. Its mycelium is susceptible to certain ‘prompts’ that allow it to identify a specific food source and move towards it. Its spores can only germinate on certain kinds of wood, and under particular conditions of moisture and temperature. It has already travelled an evolutionary marathon alongside its hosts and cannot be diverted into a sudden sprint elsewhere. One measure of its exquisite adaptations is that it has a ‘wild’ close relative, Serpula himantioides, that does not cause much domestic chaos, but mostly lingers harmlessly in woodland on fallen trunks: it is another specialist that knows its own place, and does not feud with its more damaging relative. It is quite dramatic enough that Dry Rot Fungus can bring the house down.

Serpula lacrymans may not be native to the United Kingdom. It is, after all, never found in woods and parks in our islands, but specialises in causing havoc in interiors, an ‘unnatural’ habitat. Recent molecular evidence gleaned from collections around the world has shown that our destructive fungus may be identical to one found in natural habitats as a degrader of conifer wood in the Far East and the Himalayas. Another, North American variety is apparently not so determined to do damage to housing. Even if our movie proposal is impossible, fungal invasion can still happen if the fungus doesn’t have to leap organism but simply trade location. Given a suitable habitat, a spore will eventually find its way there: crumbling timbers follow inexorably. The destructive species was given a boost by the Second World War, when bomb damage gifted the Dry Rot Fungus as much food as it wanted. Stately homes were abandoned in the aftermath, when His Lordship moved into a comfortable modern bungalow in the grounds so he no longer had to worry. Molecular studies have also proved that Serpula is more closely related to the boletes – including the Cep with which this book began – than to either gilled mushrooms or puffballs, while resembling none of these familiar fungi in any obvious way. What shape shifters fungi are!

Wood infected with dry rot is distinctive. Where it has been invaded by mycelium, it characteristically shrinks and cracks, often breaking up into little dice-sized cubes. Afflicted wood changes to a typically warm brown colour, and when it eventually loses coherence it can be crumbled into dust. Even if there is no physical evidence of the fungus responsible, cracked, brown wood can be readily spotted on walks through pinewoods, especially in forests that have been neglected, which allows fallen trunks the time to decay. The fungi responsible for breaking down wood in this fashion are the brown rot fungi (BRF) that I shall simply call brown rotters. Less than 10 per cent of fungal species that break down wood are brown rotters. This is a sketch of how they work. The structural components of wood include three dominant molecules: cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. They are what give wood its mechanical strength, engineer its water-transporting abilities, protect its internal chemistry and determine its rates of growth.

Of these, cellulose is the most abundant biopolymer on Earth, widely distributed in algae and higher plants; in wood it can make up to 50 per cent of the bulk. The structure of cellulose is important for its strengthening function, as it consists of chains of hundreds, or even thousands, of simple, conjoined glucose-like (‘sugar’) molecules – technically, it is a polysaccharide. It is wood’s scaffolding and building material combined. Hemicellulose works alongside: a more complex molecule with a branched structure, and including a varied array of sugar-like molecules. Brown rotters dismantle both of these components of wood and utilise the sugars and energy released to build their own carbon compounds from this plunder. What the sun’s photosynthetic generosity and the long-term growth of the tree joined together these fungi put asunder. A simplified view of this stratagem of decomposition is that the third woody component – lignin – remains behind, and is responsible for both the colour and substance of the emasculated wood that we notice on our woodland walks.[1]

In our Grim’s Dyke Wood we leave the branches that have broken off our trees to rot away in their own time. Over a year or so we get to see many different saprotrophic fungi that make a living from breaking down wood, and have to remind ourselves that even when we can see no evidence of fruiting, the mycelium is working away inside the tissues of fallen branches, extracting what it needs, and that sooner or later we will be rewarded with mushrooms that allow us to finger the guilty party. We have only a couple of oak trees, but we recently spotted one moderately substantial fallen branch a few feet in length that was lying half concealed by brambles. When I grasped it, I was astonished at how little it weighed. I expected a cudgel and got a wand. Although it still retained some bark, the wood at one of its broken ends was easily visible. Quite unlike the solid oak that makes furniture and supports cottages, this was pale and delicate, a fibrous ghost of Hearts of Oak. Its substance had been sucked away, leaving a spectre of oakiness, a failed promise of robustness, a fragile simulacrum.

My branch had been processed by one of the white rot fungi (‘white rotters’ herein). The cellulose and hemicellulose of the original wood had been almost entirely consumed, but, in addition, the lignin had been bleached of its character and broken down into its component parts. This was as far as fungi can go to exploit the creative work carried out by years of photosynthesis in the canopy; it was almost the end point of recycling. I looked again at my featherweight branch. There was a white patch as large as a beermat on what must have been its underside when it was lying on the ground. At this point my hand lens was brought into play. (I still call it a hand lens, following the example of my first biology teacher, though many people know it as a jeweller’s loupe.)

The white patch was revealed as a delicate maze, a miniature white labyrinth with a hundred tiny walls. This was the spore-bearing surface of one of the white rotters, whose mycelium must have drained my oak branch of its strength and colour, leaving behind only a few wispy struts of white cellulose. The maze-like surface identified it as the Split Porecrust (Schizopora paradoxa), one of the commonest white rotters in English woodlands. It had no stem, nor did it bear any cap or bracket, it was just this thin patch adhering to the underside of the branch where it would have been hidden from the light among the leaf litter to shed its spores into the darkness. It is described in the textbooks as one of the resupinate fungi, and indeed it is supine in the sense that it is not elevated above the rotten branch to which it is attached, but if supine means lying flat on your back staring upwards, then this fungus was doing just the opposite – attached by its back and facing downwards. It is one of those fungi that people pass by without noticing, unless they start turning over rotting wood lying on the ground. Then it is likely to be found within ten minutes in the autumn or early winter. To examine it properly a microscope slide is easily made from a small piece of the tissue from a wall of the ‘maze’, and under high power it can be quickly determined that the Porecrust is a typical basidio with small, colourless spores. Tiny black mites graze upon these spores, like grotesque, spiky little cows, and once I spotted an equally diminutive pseudoscorpion on the same sample equipped with fearsome pincers that was clearly in pursuit of the ‘cows’; so this inconspicuous upside-down fungus was evidently the basis of a Lilliputian ecosystem. Thus my one small oak branch was both recycled and made into a microhabitat of unsuspected diversity.

There are many more species of white rotters than brown rotters, but both kinds of rot are overwhelmingly the territory of the spore droppers, the basidios.[2] Hundreds of species have adopted this mode of saprotrophic life, almost as many as those that form mycorrhizal partnerships. They ensure that the cycling of natural materials pursues its leisurely course: what goes around comes around. The various species of rotters display the whole gamut of fungal form: they can be brackets, shelves or toadstools that may be soft and yielding, or crusty and hard; they can bear their spores in tubes, on spines or gills. Many of them face downwards as they grow, like the Split Porecrust, and pose particular challenges for identification, though few destroy wood so definitively. It is generally accepted that both kinds of rotters have originated several times during the evolution of the fungi, so it is a way of earning a living rather than a sign of a close evolutionary relationship. However, rot is also taxonomically significant, as no one genus includes species with both white and brown rotters. When I recognised the importance of these fungi in nature, I toyed with the idea of calling this book simply Rot, until it was pointed out to me by a well-wisher that I could scarcely say I was ‘busy writing Rot at the moment’.

Some rotters are very widespread. The white rotter Splitgill (Schizophyllum commune) is found all over the world. This fungus forms tiers of small, whitish, scurfy brackets on wood, and the common name refers to the fact that the pale-purplish gills are indeed neatly split along their edges, especially when dry. It is a remarkable fungus in many ways. It can be revived with moisture after being kept dry for more than a year (some reports say a decade or more). It has more sexes than any other organism, that is, 23,328, according to one researcher. This refers to different mycelial ‘mating types’ that can only combine with another, compatible mating type to produce viable fruit bodies. None of my books say it is edible, but I saw a bucket of dry Splitgill on sale in a street market at Luang Prabang in Laos, and I understood from local intelligence that it was a favourite in omelettes and much used in traditional medicine. Schizophyllum can be found on wood from the tropics to high latitudes. It has even been reported from whale bones! As so often with widespread species, there is a debate as to whether there are ‘cryptic species’ in different parts of the world, distinguishable at the genomic level. All I can say is that these little fungi look exactly the same wherever I have come across them. The Oyster Mushroom is another familiar white rotter that is almost as widespread, but, as I have said elsewhere, it is typical during the earlier stages of timber breakdown and hence not found in association with the kind of end-of-the-line wood I described for the Split Porecrust. It is one of the least fussy of cellulose feeders, however, and so of particular use in ‘cleaning up’ organic waste, not to mention food production from woody waste materials.

White rotters have at their disposal a greater chemical armoury than brown rotters. It is helpful to think of the enzymes they deploy as a kind of toolkit that can be used to dismantle large molecules into convenient and useful pieces. Different tools are used for different purposes, but most have the function of degrading complex chemicals by cutting the bonds that hold their structures together. Organic molecules often have structures that are portrayed as huge and frequently irregular climbing frames with atoms at their joints, which is a visual model used for convenience rather than a literal description of the molecule in question. Nonetheless, it is acceptable to think of enzymes as a set of secateurs laying into the target molecules, cutting and shaping. I imagine fungal hyphae as wielders of molecular instruments of degradation as if they were a kind of demolition squad retrieving sugar bricks from cellulose for further use, or capturing nutritious chemical elements that could be redeployed in making a fruit body. Fungal hyphae delve into, and joust with, complex organic molecules. Lignin is the most complex puzzle of all, a polymer far more multifarious than cellulose, dangling with benzene rings and subsidiary branches that only make sense to an organic chemist. There are different kinds of lignin, some of which are only now yielding their secrets. No matter: there is a white rotter to take them on and cut them down to size.

If fruiting fungi provide the most obvious display of rotters at work, hidden dramas are played out within the interior of ageing trees or prostrate logs long before a blatant show of brackets or mushrooms unveils the stars of decomposition. Mycelium is at work on the available wood, recruiting nutrients and growing as it does so, guzzling through a woody volume to take over as much as it can to further its own eventual fruition. Visualise three-dimensional territories dividing a tree trunk into separate realms, wherein one fungus species takes command, seeking to repel unwanted invaders. Questing mycelium can recognise its own kind, a friend, but can also detect a rival for its resources, an enemy. There will be confrontations, vying for position, fast-growing mycelium trying to outflank its rivals for territory, or slower-growing mycelium using a chemical arsenal to deter its speedier rival. Lynne Boddy, the University of Cardiff professor who has done so much to understand these confrontations, refers to the competitions playing out in dead wood as ‘fungus wars’.

In Grim’s Dyke Wood we have been obliged to fell ailing beech trees. One of these had a trunk that looked reasonably sound when the tree was standing, but the felled tree showed a hole at its centre, proving decay was already underway Even an apparently sound tree showed characteristic outlines on its cut surface. The cross-section of the trunk revealed thin black lines unrelated to the obvious tree rings marking its annual growth, and these divided the surface of the cut tree into perhaps half a dozen or more territories. If it were a map, they could have been coloured in with distinctive hues and named as different countries. Projected into three dimensions they would be cylinders of wood, delimited from their neighbours by thin sheets rather than lines. Each cylinder embraced one mycelial individual, its lines black, produced by the pigment melanin, and marking out the territory occupied by that one mycelium. They are the equivalent of a notice saying: ‘Private. Keep Out. Trespassers will be prosecuted.’ Such marked wood is familiar to wood turners, who refer to it as ‘spalted’ and value it for making interesting wooden bowls. It is a matter of delicate timing to find the desirable raw material before degradation of the wood has gone too far.

Lynne has set up experiments to understand how mycelium behaves in wood. It is a dynamic system. If a new food source (a wooden block) is made available, the mycelium from an established source will grow preferentially towards it and other parts of the mycelial system will begin to shrink. It is opportunistic behaviour, based on hyphal tips being sensitive to foods that will promote further expansion of the individual mycelium: more branching, more absorption of nutrients. Resources are moved via the mycelium network to the most profitable position at the front line. Further questing leads to preferential growth: the Dry Rot Fungus can pass through walls to reach new wood to destroy, in this case without a rival.

Under natural conditions, competition rules. Even different individuals of the same species fight for territory. If more than one species is involved in the experiment, there will be winners and losers. If conditions are changed, so might the species having the more successful outcome. Some are more tolerant of high or low temperatures, others more susceptible to drying out. Over time, one fungus will be replaced by a successor in an ecological duel. Some of the winners are commonly seen on fallen wood: the abundant Turkey Tail bracket displaces the equally common Hairy Curtain Crust, but since the latter is usually among the first to colonise freshly fallen (or cut) branches, both species have ample opportunity to spread their spores. The Stinkhorn trumps the Whitelaced Shank (Megacollybia platyphylla), although both quest through leaf litter and twigs with similar-looking white, stringy fibres of mycelium. As more species are added to the competition, the possibilities for rivalry and interaction multiply exponentially. In a wood on a warm and humid autumn day the tranquil atmosphere will conceal all manner of frenetic interactions between dozens of different mycelia vying for space and nutrients. The quiet wood conceals deadly conflict! A standing dead beech might seem lifeless but in its interior a score of species will be trying to establish supremacy. Spores arriving on the breeze will germinate and may prosper briefly only to be ousted by a rival. Now that fungi can be identified from their DNA, samples taken from wood that includes growing hyphae can identify the actors in this hidden drama before they have a chance to reveal themselves.

Many more kinds lurk within the wood than would be expected, judging from the meagre number of species of brackets or toadstools that finally erupt from the trunk of the tree. Which fungus finally gets to release its spores must depend on a hundred battles fought unseen. Fungi even lurk in waiting for years for their moment to come, surviving as mycelium in nooks and crannies in living trees (even inside living plant cells) until the tree begins to age, when they will start to join the battle for supremacy in the woody boxing ring.

When there is a life-or-death competition there will be a premium on getting an edge over rivals. In the early stages of decay some nutrients – such as nitrogen – are in short supply. Mugging a nematode eelworm might be the remedy. I frequently see nematodes under the microscope when I am examining fungus samples: tiny (less than 2 mm long), slowly thrashing, transparent, tapering thread-like animals that are very abundant within woody tissue. Within the secret depths of decaying wood, the Oyster Mushroom has evolved a way of capturing, killing and consuming nematodes to help its network gain an advantage over its rivals. Some Oyster hyphae produce specialised hourglass-shaped outgrowths, and if a nematode brushes by one of these it first becomes stuck by a glue-like substance and within a short time is immobilised by a paralysing toxin. Then the helpless worm is penetrated by hyphae growing from the point of attachment and, as if by a lethal vacuum cleaner, the contents are removed to supply nourishment to the network. If that sounds grisly, other fungi have evolved loops that tighten rapidly if an eelworm passes through, then to be drained dry of the goodness it contains. I could add spores that stick in the gullets of the unfortunate worm only to germinate and dine upon their consumers. There are dozens of mycological monsters that have learned to take advantage of these tiny worms. Capture and consumption are just another ruse to nudge ahead in the ‘fungus wars’.

By the time a sequence of rotters have been at work on a log for several years, it has lost much of its substance. The remains of what was once firm wood have become soft and spongy: a finger can be pushed into the mush without too much resistance. This has one advantage for fungi because such wood readily absorbs rainwater – even a short shower leaves behind a moist, crumbling cake through which mycelium can move with dispatch. Patches of ghostly fungi like white cobwebs decorate damp corners. Tiny white discos dust the lower surfaces. Some toadstools prefer such a late stage in the life of a log and are able to dine on the leftovers from the generations of different fungi that preceded them. Nothing is wasted. In dismal corners of woodland, dripping with damp, some of these toadstools shine bright as lamps: shields (Pluteus) can be white, yellow or red, as well as every shade of brown, and all eventually have pink gills that fall short of the stem. Many are fragile, as if the effort of making flesh out of very old degraded wood could not produce anything of real substance.

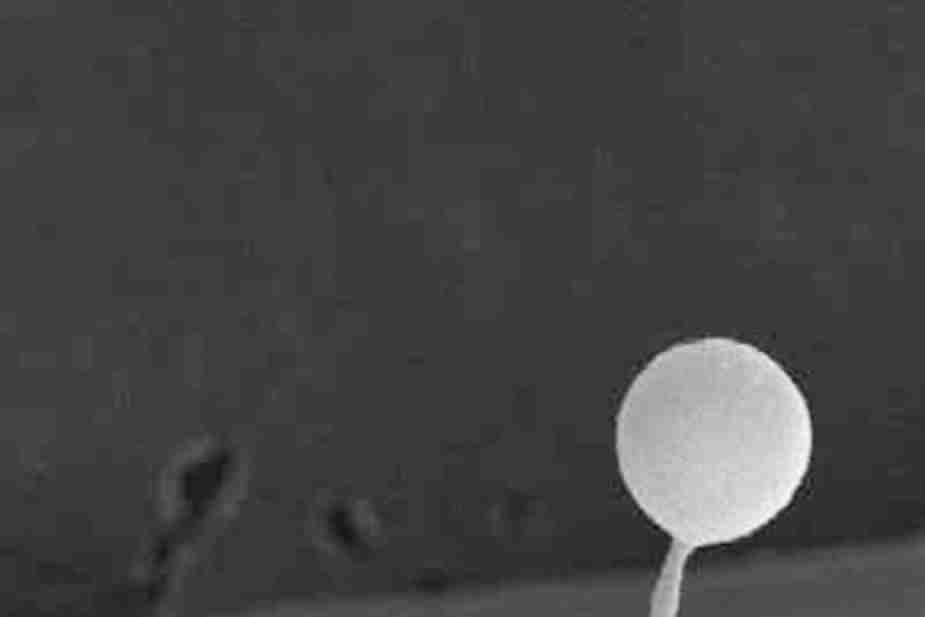

Electron microscope image of toxocysts on the mycelium of the Oyster Mushroom that target nematode worms. Courtesy Huen-Ping Hsueh.

What I believe to be the most beautiful mushroom of all grows from knotholes in dead or dying trees, often from well-rotted wood remaining in the interior of a standing relic. It is a rare fungus. Every mushroom lover will remember seeing it in the flesh for the first time. I knew the black and white photograph of it in John Ramsbottom’s Mushrooms and Toadstools from my early days, and always yearned to find it. I failed to do so until I was in my middle age. It did not disappoint. In the Chilterns, several mushrooms were rising out of the remains of an ancient beech tree, which was long dead and much decayed, but still upright. They could not be missed in dimly illuminated summer woodland because they were shining white from afar; the largest was the size of my outstretched hand. The caps were opened into a wide parabola. Extraordinarily, the fungus had arisen out of a thick, cup-like volva, like the Death Cap – in fact, there was an as-yet unexpanded ‘egg’ nearby that was entirely covered by an off-white membrane, through which the mushroom would erupt, pushing upwards as the cap expanded. Unlike the Death Cap, there was no ring on the firm stipe: and the free gills were pink in colour (as was the spore print). This Silky Rosegill (Volvariella bombycina) was no poisonous temptress dressed in virginal white, it belonged to another group of fungi from the deadly Amanitas. What made it altogether exceptional is expressed in the ‘silky’ part of the name: the surface of the cap was decked completely in delicate, short, white hairs running down its surface, so perfect that it looked as if it must have been carefully groomed by some sprite of the woods. Not a hair was out of place. My close encounter with the perfect mushroom on beech was followed by one almost as beautiful on an oak, a tree that had been struck by lightning several years earlier. How could I possibly think of such a paragon as a rotter?