[Known only from the O.P. The original is lost.]

Most illustrious Sir, esteemed friend,

With such reluctance did I recently tear myself away from your side when visiting you at your retreat in Rijnsburg, that no sooner am I back in England than I am endeavouring to join you again, as far as possible, at least by exchange of letters. Substantial learning, combined with humanity and courtesy—all of which nature and diligence have so amply bestowed on you—hold such an allurement as to gain the affection of any men of quality and of liberal education. Come then, most excellent Sir, let us join hands in unfeigned friendship, and let us assiduously cultivate that friendship with devotion and service of every kind. Whatever my poor resources can furnish, consider as yours. As to the gifts of mind that you possess, let me claim a share in them, as this cannot impoverish you.

At Rijnsburg we conversed about God, about infinite Extension and Thought, about the difference and agreement of these attributes, and about the nature of the union of the human soul with the body; and also about the principles of the Cartesian and Baconian philosophy. But since we then spoke about such important topics as through a lattice-window and only in a cursory way, and in the meantime all these things continue to torment me, let me now, by the right of the friendship entered upon between us, engage in a discussion with you and cordially beg you to set forth at somewhat greater length your views on the above-mentioned subjects. In particular, please be good enough to enlighten me on these two points: first, wherein you place the true distinction between Extension and Thought, and second, what defects you find in the philosophy of Descartes and Bacon, and how you consider that these can be removed and replaced by sounder views. The more frankly you write to me on these and similar subjects, the more closely you will bind me to you and place me under a strong obligation to make an equal return, if only I can.

Here there are already in the press Certain Physiological Essays,1 written by an English nobleman, a man of extraordinary learning. These treat of the nature of air and its elastic property, as proved by forty-three experiments; and also of fluidity and firmness and the like. As soon as they are printed, I shall see to it that they are delivered to you through a friend who happens to be crossing the sea. Meanwhile, farewell, and remember your friend, who is,

Yours in all affection and devotion,

Henry Oldenburg

London, 16/26 August 1661

[Known only from the O.P. The original is lost. No date is given, but a conjectural date is September 1661.]

Esteemed Sir,

You yourself will be able to judge what pleasure your friendship affords me, if only your modesty will allow you to consider the estimable qualities with which you are richly endowed. And although, with these qualities in mind, I feel myself not a little presumptuous in venturing upon this relationship, especially when I reflect that between friends all things, and particularly things of the spirit, should be shared, nevertheless this step is to be accredited not so much to me as to your courtesy, and also your kindness. From your great courtesy you have been pleased to belittle yourself, and from your abundant kindness so to enlarge me, that I do not hesitate to enter upon the friendship which you firmly extend to me and deign to ask of me in return, a friendship which it shall be my earnest endeavour diligently to foster.

As for my mental endowments, such as they are, I would most willingly have you make claim on them even if I knew that this would be greatly to my detriment. But lest I seem in this way to want to refuse you what you ask by right of friendship, I shall attempt to explain my views on the subjects we spoke of—although I do not think that this will be the means of binding you more closely to me unless I have your kind indulgence.

I shall begin therefore with a brief discussion of God, whom I define as a Being consisting of infinite attributes, each of which is infinite or supremely perfect in its own kind.2 Here it should be observed that by attribute I mean every thing that is conceived in itself and through itself, so that its conception does not involve the conception of any other thing. For example, extension is conceived through itself and in itself, but not so motion; for the latter is conceived in something else, and its conception involves extension.3

That this is a true definition of God is evident from the fact that by God we understand a supremely perfect and absolutely infinite Being. The existence of such a Being is easily proved from this definition; but as this is not the place for such a proof,4 I shall pass it over. The points I need to prove here in order to satisfy your first enquiry, esteemed Sir, are as follows: first, that in Nature there cannot exist two substances without their differing entirely in essence; secondly, that a substance cannot be produced, but that it is of its essence to exist; third, every substance must be infinite, or supremely perfect in its kind.5

With these points established, esteemed Sir, provided that at the same time you attend to the definition of God, you will readily perceive the direction of my thoughts, so that I need not be more explicit on this subject. However, in order to provide a clear and concise proof, I can think of no better expedient than to arrange them in geometrical style and to submit them to the bar of your judgment. I therefore enclose them separately herewith6 and await your verdict on them.

Secondly, you ask me what errors I see in the philosophy of Descartes and Bacon. In this request, too, I shall try to oblige you, although it is not my custom to expose the errors of others. The first and most important error is this, that they have gone far astray from knowledge of the first cause and origin of all things. Secondly, they have failed to understand the true nature of the human mind. Thirdly, they have never grasped the true cause of error. Only those who are completely destitute of all learning and scholarship can fail to see the critical importance of true knowledge of these three points.

That they have gone far astray from true knowledge of the first cause and of the human mind can readily be gathered from the truth of the three propositions to which I have already referred; so I confine myself to point out the third error. Of Bacon I shall say little; he speaks very confusedly on this subject, and simply makes assertions while proving hardly anything. In the first place he takes for granted that the human intellect, besides the fallibility of the senses, is by its very nature liable to error, and fashions everything after the analogy of its own nature, and not after the analogy of the universe, so that it is like a mirror presenting an irregular surface to the rays it receives, mingling its own nature with the nature of reality, and so forth.7 Secondly, he holds that the human intellect, by reason of its peculiar nature, is prone to abstractions,8 and imagines as stable things that are in flux, and so on. Thirdly, he holds that the human intellect is in constant activity, and cannot come to a halt or rest.9 Whatever other causes he assigns can all be readily reduced to the one Cartesian principle, that the human will is free and more extensive than the intellect, or, as Verulam more confusedly puts it, the intellect is not characterised as a dry light, but receives infusion from the will.10 (We should here observe that Verulam often takes intellect for mind, therein differing from Descartes.) This cause, then, disregarding the others as being of little importance, I shall show to be false. Indeed, they would easily have seen this for themselves, had they but given consideration to the fact that the will differs from this or that volition in the same way as whiteness differs from this or that white object, or as humanity differs from this or that human being. So to conceive the will to be the cause of this or that volition is as impossible as to conceive humanity to be the cause of Peter and Paul.11

Since, then, the will is nothing more than a mental construction (ens rationis), it can in no way be said to be the cause of this or that volition. Particular volitions, since they need a cause to exist, cannot be said to be free; rather, they are necessarily determined to be such as they are by their own causes. Finally, according to Descartes, errors are themselves particular volitions, from which it necessarily follows that errors—that is, particular volitions—are not free, but are determined by external causes and in no way by the will. This is what I undertook to demonstrate. Etc.

[Known only from the O.P. The original is lost.]

Excellent Sir and dear friend,

Your very learned letter has been delivered to me and read with great pleasure. I warmly approve your geometrical style of proof, but at the same time I blame my obtuseness for not so readily grasping what you with such exactitude teach. So I beg you to allow me to present the evidence of this sluggishness of mine by putting the following questions and seeking from you their solutions.

The first is, do you understand clearly and indubitably that, solely from the definition of God which you give, it is demonstrated that such a Being exists? For my part, when I reflect that definitions contain no more than conceptions of our mind, and that our mind conceives many things that do not exist and is most prolific in multiplying and augmenting things once conceived, I do not yet see how I can infer the existence of God from the conception I have of him. Indeed, from a mental accumulation of all the perfections I discover in men, animals, vegetables, minerals and so on, I can conceive and form one single substance which possesses in full all those qualities; even more, my mind is capable of multiplying and augmenting them to infinity, and so of fashioning for itself a most perfect and excellent Being. Yet the existence of such a Being can by no means be inferred from this.

My second questions is, are you quite certain that Body is not limited by Thought, nor Thought by Body? For it is still a matter of controversy as to what Thought is, whether it is a corporeal motion or a spiritual activity quite distinct from what is corporeal.

My third question is, do you regard those axioms you have imparted to me as being indemonstrable principles, known by the light of Nature and standing in no need of proof? It may be that the first axiom is that of kind, but I do not see how the other three can be accounted as such. For the second axiom supposes that there exists in Nature nothing but substance and accidents, whereas many maintain that time and place are in neither category. Your third axiom, that ‘things having different attributes have nothing in common’ is so far from being clearly conceived by me that the entire Universe seems rather to prove the contrary. All things known to us both differ from one another in some respects and agree in other respects. Finally, your fourth axiom, namely, ‘things which have nothing in common with one another cannot be the cause one of the other’, is not so clear to my befogged intellect as not to require some light to be shed on it. For God has nothing formally in common with created things; yet we almost all hold him to be their cause.

Since, then, these axioms do not seem to me to be placed beyond all hazard of doubt, you may readily conjecture that your propositions based on them are bound to be shaky. And the more I consider them, the more I am overwhelmed with doubt concerning them. Against the first I hold that two men are two substances and of the same attribute, since they are both capable of reasoning; and thence I conclude that there are two substances of the same attribute. With regard to the second I consider that, since nothing can be the cause of itself, we can scarcely understand how it can be true that ‘Substance cannot be produced, nor can it be produced by any other substance.’ For this proposition asserts that all substances are causes of themselves, that they are each and all independent of one another, and it makes them so many Gods, in this way denying the first cause of all things.

This I willingly confess I cannot grasp, unless you do me the kindness of disclosing to me somewhat more simply and more fully your opinion regarding this high matter, explaining what is the origin and production of substances, the interdependence of things and their subordinate relationships. I entreat you, by the friendship on which we have embarked, to deal with me frankly and confidently in this, and I urge you most earnestly to be fully convinced that all these things which you see fit to impart to me will be inviolate and secure, and that I shall in no way permit any of them to become public to your detriment or injury.

In our Philosophical Society we are engaged in making experiments and observations as energetically as our abilities allow, and we are occupied in composing a History of the Mechanical Arts, being convinced that the forms and qualities of things can best be explained by the principles of mechanics, that all Nature’s effects are produced by motion, figure, texture and their various combinations, and that there is no need to have recourse to inexplicable forms and occult qualities, the refuge of ignorance.

I shall send you the book I promised as soon as your Dutch ambassadors stationed here dispatch a messenger to the Hague (as they often do), or as soon as some other friend, to whom I can safely entrust it, goes your way.

Please excuse my prolixity and frankness, and I particularly urge you to take in good part, as friends do, what I have said frankly and without any disguise or courtly refinement, in replying to your letter. And believe me to be, sincerely and simply,

Your most devoted,

Henry Oldenburg

London, 27 September 1661

To the noble and learned Henry Oldenburg, from B.d.S.

[Known only from the O.P. The original is lost. No date is given, but a conjectural date is October 1661.]

Most esteemed Sir,

While preparing to go to Amsterdam to spend a week or two there, I received your very welcome letter and read your objections to the three propositions which I sent you. On these alone I shall try to satisfy you, omitting the other matters for want of time.

To your first objection, then, I say that it is not from the definition of any thing whatsoever that the existence of the defined thing follows, but only (as I demonstrated in the Scholium which I attached to the three propositions) from the definition or idea of some attribute; that is (as I explained clearly in the case of the definition of God), from the definition of a thing which is conceived through itself and in itself. The ground for this distinction I have also stated in the aforementioned Scholium with sufficient clarity, I think, especially for a philosopher. A philosopher is supposed to know what is the difference between fiction and a clear and distinct conception, and also to know the truth of this axiom, to wit, that every definition, or clear and distinct idea, is true. Once these points are noted, I do not see what more is required in answer to the first question.

I therefore pass on to the solution of the second question. Here you seem to grant that, if Thought does not pertain to the nature of Extension, then Extension will not be limited by Thought; for surely it is only the example which causes you some doubt. But I beg you to note, if someone says that Extension is not limited by Extension, but by Thought, will he not also be saying that Extension is not infinite in an absolute sense, but only insofar as it is Extension? That is, does he not grant me that Extension is infinite not in an absolute sense, but only insofar as it is Extension, that is, infinite in its own kind?12

But, you say, perhaps Thought is a corporeal activity. Let it be so, although I do not concede it; but this one thing you will not deny, that Extension, insofar as it is Extension, is not Thought; and this suffices to explain my definition and to demonstrate the third proposition.

The third objection which you proceed to raise against what I have set down is this, that the axioms should not be accounted as ‘common notions’ (notiones communes).13 This is not the point I am urging; but you also doubt their truth, and you even appear to seek to prove that their contrary is more probable. But please attend to my definition of substance and accident,14 from which all these conclusions follow. For by substance I understand that which is conceived through itself and in itself, that is, that whose conception does not involve the conception of another thing; and by modification or accident I understand that which is in something else and is conceived through that in which it is. Hence it is clearly established, first, that substance is prior in nature to its accidents; for without it these can neither exist nor be conceived. Secondly, besides substance and accidents nothing exists in reality, or externally to the intellect; for whatever there is, is conceived either through itself or through something else, and its conception either does or does not involve the conception of another thing. Thirdly, things which have different attributes have nothing in common with one another;15 for I have explained an attribute as that whose conception does not involve the conception of another thing. Fourth and last, of things which have nothing in common with one another, one cannot be the cause of another; for since in the effect there would be nothing in common with the cause, all it would have, it would have from nothing.

As for your contention that God has nothing formally in common with created things, etc., I have maintained the exact opposite in my definition. For I said that God is a Being consisting of infinite attributes, each of which is infinite, or supremely perfect, in its kind.

As to your objection to my first proposition, I beg you, my friend, to consider that men are not created, but only begotten, and that their bodies already existed, but in a different form.16 However, the conclusion is this, as I am quite willing to admit, that if one part of matter were to be annihilated, the whole of Extension would also vanish at the same time.

The second proposition does not make many gods, but one only, to wit, a God consisting of infinite attributes, etc.

[Known only from the O.P. The original is lost.]

My very dear friend,

Receive herewith the little book17 I promised, and send me in return your opinion of it, especially with regard to the experiments he concludes concerning nitre, fluidity and solidity. I am most grateful to you for your learned second letter, which I received yesterday. Still, I very much regret that your journey to Amsterdam prevented you from answering all my doubts. I beg you to send me, as soon as your leisure permits, what was then omitted. Your last letter did indeed shed a great deal of light for me, but not so much as to dispel all the darkness. This will, I hope, be the happy outcome when you will have clearly and distinctly furnished me with your views on the true and primary origin of things. For as long as it is not quite clear to me from what cause and in what manner things began to be, and by what connection they depend on the first cause, if there be such a thing, then all that I hear and all that I read seems to me quite incoherent. I therefore most earnestly beg you, most learned Sir, to light my way in this matter, and not to doubt my good faith and gratitude. I am,

Your very devoted,

Henry Oldenburg

London 11/21 October 1661

[Printed in the O.P. The original is extant. The last two paragraphs of this translation appear only in the original. The letter is undated, but a conjectural date is early 1662.]

Esteemed Sir,

I have received the very talented Mr. Boyle’s book, and read it through, as far as time permitted. I thank you very much for this gift. I see that I was not wrong in conjecturing, when you first promised me this book, that you would not concern yourself with anything less than a matter of great importance. Meanwhile, learned Sir, you wish me to send you my humble opinion on what he has written. This I shall do, as far as my slender ability allows, noting those points which seem to me obscure or insufficiently demonstrated; but I have not as yet been able to peruse it all, far less examine it, because of my other commitments. Here, then, is that I find worthy of comment regarding Nitre, etc.

Of Nitre

First, he gathers from his experiment on the redintegration of Nitre that Nitre is a heterogeneous thing, consisting of fixed and volatile parts. Its nature, however (at least as shown by its behaviour), is quite different from the nature of its component parts, although it arises from nothing but a mixture of these parts. For this conclusion to be regarded as valid, I suggest that a further experiment seems to be required to show that Spirit of Nitre is not really Nitre, and cannot be reduced to solid state or crystallised without the help of salt of lye. Or at least one ought to have enquired whether the quantity of fixed salt remaining in the crucible is always found to be the same from the same quantity of Nitre, and to vary proportionately with the quantity of Nitre. And as to what the esteemed author says (section 9) he discovered with the aid of scales, and the fact that the observed behaviour of Spirit of Nitre is so different from, and even sometimes contrary to, that of Nitre itself, in my view this does nothing to confirm his conclusion.

To make this clear, I shall briefly set forth what occurs to me as the simplest explanation of this redintegration of Nitre, and at the same time I shall add two or three quite easy experiments by which this explanation is to some extent confirmed. To explain what takes place as simply as possible, I shall posit no difference between Spirit of Nitre and Nitre itself other than that which is sufficiently obvious; to wit, that the particles of the latter are at rest whereas those of the former, when stirred, are in a state of considerable commotion. With regard to the fixed salt, I shall suppose that this in no way contributes to constituting the essence of Nitre. I shall consider it as the dregs of Nitre, from which the Spirit of Nitre (as I find) is itself not free; for they float in it in some abundance, although in a very powdery form. This salt, or these dregs, have pores or passages hollowed out to the size of the particles of Nitre. But when the Nitre particles were driven out of them by the action of fire, some of the passages became narrower and consequently others were forced to dilate, and the substance or walls of these passages became stiff and at the same time very brittle. So when Spirit of Nitre was dropped thereon, some of its particles began to force their way through those narrower passages; and since the particles are of unequal thickness (as Descartes has aptly demonstrated),18 they first bent the rigid walls of the passages like a bow, and then broke them. When they broke them, they forced those fragments to recoil, and, retaining the motion they already had, they remained as equally incapable as before of solidifying and crystallising. The parts of Nitre which made their way through the wider passages, since they did not touch the walls of those passages, were necessarily surrounded by some very fine matter and by this were driven upwards, in the same way as bits of wood by flame or heat, and were given off as smoke. But if they were sufficiently numerous, or if they united with fragments of the walls and with particles making their way through the narrower passages, they formed droplets flying upwards. But if the fixed salt is loosened by means of water19 or air and is rendered less active, then it becomes sufficiently capable of stemming the onrush of the particles of Nitre and of compelling them to lose the motion they possessed and to come again to a halt, just as does a cannonball when it strikes sand or mud. The redintegration of Nitre consists solely in this coagulation of the particles of Spirit of Nitre, and to bring this about the fixed salt acts as an instrument, as is clear from this explanation. So much for the redintegration.

Now, if you please, let us see first of all why Spirit of Nitre and Nitre itself differ so much in taste; secondly, why Nitre is inflammable, while spirit of Nitre is by no means so. To understand the first question, it should be noted that bodies in motion never come into contact with other bodies along their broadest surfaces, whereas bodies at rest lie on other bodies along their broadest surfaces. So particles of Nitre, if placed on the tongue while they are at rest, will lie on it along their broadest surfaces and will thus obstruct its pores, which is the cause of the cold sensation. Furthermore, the Nitre cannot be dissolved by saliva into such very minute particles. But if the particles are placed on the tongue while they are in active motion, they will come into contact with it by their more pointed surfaces and will make their way through its pores. And the more active their motion, the more sharply they will prick the tongue, just as a needle, as it either strikes the tongue with its point or lies lengthwise along the tongue, will cause different sensations to arise.

The reason why Nitre is inflammable and the Spirit of Nitre not so is this, that when particles of Nitre are at rest, they cannot so readily be borne upwards by fire as when they have their own motion in all directions. So when they are at rest, they resist the fire until such time as the fire separates them from one another and encompasses them from all sides. When it does encompass them, it carries them with it this way and that until they acquire a motion of their own and go up in smoke. But the particles of the Spirit of Nitre, being already in motion and separate from one another, are dilated in every direction in increased volume by a little heat of the fire; and thus some go up in smoke while others penetrate the matter supplying the fire before they can be completely encompassed by flame, and so they extinguish the fire rather than feed it.

I shall now pass on to experiments which seem to confirm this explanation. First, I found that the particles of Nitre which go up in smoke with a crackling noise are pure Nitre. For when I melted the Nitre again and again until the crucible became white-hot, and I kindled it with a live coal,20 I collected its smoke in a cold glass flask until the flask was moistened thereby, and after that I moistened the flask yet further by breathing on it, and finally set it out to dry in the cold air.21 Thereupon little icicles22 of Nitre appeared here and there in the flask. Now it might be thought that this did not result solely from the volatile particles, but that the flame could be carrying with it whole particles of Nitre (to adopt the view of the esteemed author) and was driving out the fixed particles, along with the volatile, before they were dissolved. To remove such a possibility, I caused the smoke to ascend through a tube (A) over a foot long, as through a chimney, so that the heavier particles adhered to the tube, and I collected only the more volatile parts as they passed through the narrower aperture (B). The result was as I have said.

Even so, I did not stop at this point, but, as a further test, I took a larger quantity of Nitre, melted it, ignited it with a live coal and, as before, placed the tube (A) over the crucible; and as long as the flame lasted, I held a piece of mirror close to the aperture (B). To this some matter adhered which, on being exposed to air, became liquid. Although I waited some days, I could not observe any sign of Nitre; but when I added Spirit of Nitre to it, it turned into Nitre.

From this I think I can infer, first, that in the process of melting the fixed parts are separated from the volatile and that the flame drives them upwards separately from one another; secondly, that after the fixed parts are separated from the volatile with a crackling noise, they can never be reunited. From this we can infer, thirdly, that the parts which adhered to the flask and coalesced into little icicles were not the fixed parts, but only the volatile.

The second experiment, and one which seems to prove that the fixed parts are nothing but the dregs of Nitre, is as follows. I find that the more the Nitre is purified of its dregs, the more volatile it is, and the more apt to crystallise. For when I put crystals of purified or filtered Nitre in a glass goblet, such as A, and poured in a little cold water, it partly evaporated along with the cold water, and the particles escaping upwards stuck to the rim of the glass and coalesced into little icicles.

The third experiment, which seems to show that when the particles of Nitre lose their motion they become inflammable, is as follows. I trickled droplets of Spirit of Nitre into a damp paper bag and then added sand, between whose grains the Spirit of Nitre kept penetrating; and when the sand had absorbed all, or nearly all, the Spirit of Nitre, I dried it thoroughly in the same bag over a fire. Thereupon I removed the sand and set the paper against a live coal. As soon as it caught fire it gave off sparks, just as it usually does when it has absorbed Nitre itself.

If I had had time for further experimentation, I might have added other experiments which would perhaps make the matter quite clear. But as I am very much occupied with other matters, you will forgive me if I defer it for another time and proceed to other comments.

Section 5. When the esteemed author discusses incidentally the shape of particles of Nitre, he criticises modern writers as having wrongly represented it. I am not sure whether he includes Descartes; if so, he is perhaps criticising Descartes from what others have said. For Descartes is not speaking of particles visible to the eye. And I do not think that the esteemed author means that if icicles of Nitre were to be rubbed down until they became parallelepipeds or some other shape, they would cease to be Nitre. But perhaps he is referring to some chemists who admit nothing but what they can see with their eyes and touch with their hands.

Section 9. If this experiment could be carried out rigorously, it would completely confirm the conclusion I sought to draw from the first experiment mentioned above.

From section 13 to 18 the esteemed author tries to prove that all tangible qualities depend solely on motion, shape and other mechanical states. Since these demonstrations are not advanced by the esteemed author as being of a mathematical kind, there is no need to consider whether they carry complete conviction. Still, I do not know why the esteemed author strives so earnestly to draw this conclusion from this experiment of his, since it has already been abundantly proved by Verulam, and later by Descartes. Nor do I see that this experiment provides us with clearer evidence than other experiments readily available. For as far as heat is concerned, is not the same conclusion equally clear from the fact that if two pieces of wood, however cold they are, are rubbed against each other, they produce a flame simply as a result of that motion? Or that lime, sprinkled with water, becomes hot? As far as sound is concerned, I do not see what is to be found in this experiment more remarkable than is found in the boiling of ordinary water, and in many other instances. As to colour, to confine myself to the obvious, I need say no more than that we see green vegetation assuming so many and such varied colours. Again, bodies that give forth a foul smell emit even a fouler smell when agitated, and especially if they become somewhat warm. Finally sweet wine turns sour, and so with many other things. All these things, therefore, I would consider superfluous, if I may use the frankness of a philosopher. This I say because I fear that others, whose regard for the esteemed author is not as great as it should be, may misjudge him.23

Section 24. I have already spoken of the cause of this phenomenon. Here I will merely add that I, too, have found by experience that particles of the fixed salt float in those saline drops. For when they flew upwards, they met a plate of glass which I had ready for the purpose. This I warmed somewhat so that any volatile matter should fly off, whereupon I observed some thick whitish matter adhering to the glass in places.

Section 25. In this section the esteemed author seems to intend to prove that the alkaline parts are driven hither and thither by the impact of the salt particles, whereas the salt particles ascend into the air by their own force. In explaining the phenomenon I too have said that the particles of Spirit of Nitre acquire a more lively motion because, on entering the wider passages, they must necessarily be encompassed by some very fine matter, and are thereby driven upwards as are particles of wood by fire, whereas the alkaline particles received their motion from the impact of particles of Spirit of Nitre penetrating through the narrower passages. Here I would add that pure water cannot so readily dissolve and soften the fixed parts. So it is not surprising that when Spirit of Nitre is poured onto the solution of the said fixed salt dissolved in water, an effervescence should take place such as the esteemed author describes in section 24. Indeed, I think this effervescence will be more violent than if Spirit of Nitre were to be added to the fixed salt while it is still intact. For in water it is dissolved into very minute molecules which can be more readily separated and more freely moved than when all the parts of the salt lie on one another and are firmly attached.

Section 26. Of the taste of the acidic Spirit I have already spoken, and so it remains only to speak of the alkali. When I placed this on the tongue, I felt a sensation of heat, followed by a prickling. This indicates to me that it is some kind of lime; for in just the same way that lime becomes heated with the aid of water, so does this salt with the aid of saliva, perspiration, Spirit of Nitre, and perhaps even moist air.

Section 27. It does not immediately follow that a particle of matter acquires a new shape by being joined to another; it only follows that it becomes larger, and this suffices to bring about the effect which is the object of the esteemed author’s inquiry in this section.

Section 33. What I think of the esteemed author’s method of philosophising I shall say when I have seen the Dissertation which is mentioned here and in the Introductory Essay, page 33.24

On Fluidity

Section 1. “It is quite manifest that they are to be reckoned among the most general states … etc.” In my view, notions which derive from popular usage, or which explicate Nature not as it is in itself but as it is related to human senses, should certainly not be regarded as concepts of the highest generality, nor should they be mixed (not to say confused) with notions that are pure and which explicate Nature as it is in itself. Of the latter kind are motion, rest, and their laws; of the former kind are visible, invisible, hot, cold, and, to say it at once, also fluid, solid, etc.

Section 5. “The first is the littleness of the bodies that compose it, for in the larger bodies … etc.” Even though bodies are small, they have (or can have) surfaces that are uneven and rough. So if large bodies move in such a way that the ratio of their motion to their mass is that of minute bodies to their particular mass, then they too would have to be termed fluid, if the word ‘fluid’ did not signify something extrinsic and were not merely adapted from common usage to mean those moving bodies whose minuteness and intervening spaces escape detection by human senses. So to divide bodies into fluid and solid would be the same as to divide them into visible and invisible.

The same section. “If we were not able to confirm it by chemical experiments.” One can never confirm it by chemical or any other experiments, but only by demonstration and by calculating. For it is by reason and calculation that we divide bodies to infinity, and consequently also the forces required to move them. We can never confirm this by experiments.

Section 6. “… great bodies are not well adapted to forming fluid bodies … etc.” Whether or not one understands by ‘fluid’ what I have just said, the thing is self-evident. But I do not see how the esteemed author confirms this by the experiments quoted in this section. For (since we want to doubt what is certain)25 although bones may be unsuitable for forming chyle and similar fluids, perhaps they will be quite well adapted for forming some new kind of fluid.

Section 10. “… and this by making them less pliant than formerly … etc.” They could have coagulated into another body more solid than oil without any change in the parts, but merely because the parts driven into the receiver were separated from the rest. For bodies are lighter or heavier according to the kinds of fluids in which they are immersed. Thus particles of butter, when floating in milk, form part of the liquid; but when the milk is stirred and so acquires a new motion to which all the parts composing the milk cannot equally accommodate themselves, this in itself brings it about that some parts become heavier and force the lighter parts to the surface. But because these lighter parts are heavier than air so that they cannot compose a liquid with it, they are forced downwards by it; and because they are ill adapted for motion, they also cannot compose a liquid by themselves, but lie on one another and stick together. Vapours, too, when they are separated from the air, turn into water, which, in relation to air, may be termed a solid.

Section 13. “And I take as an example a bladder distended with water rather than one full of air … etc.” Since particles of water are always moving ceaselessly in all directions, it is clear that, if they are not restrained by surrounding bodies, the water will spread in all directions. Moreover, I am as yet unable to see how the distention of a bladder full of water helps to confirm his view about the small spaces. The reason why the particles of water do not yield when the sides of the bladder are pressed with a finger—as they otherwise would do if they were free—is this, that there is no equilibrium or circulation as there is when some body, say our finger, is surrounded by a fluid or water. But however much the water is pressed by the bladder, yet its particles will yield to a stone also enclosed in the bladder, in the same way as they usually do outside the bladder.

Same section. “whether there is any portion of matter….” We must maintain the affirmative, unless we prefer to look for a progression to infinity, or to grant that there is a vacuum, than which nothing can be more absurd.

Section 19. “… that the particles of the liquid find admittance into those pores and are held there (by which means … etc.)” This is not to be affirmed absolutely of all liquids which find admittance into the pores of other bodies. If the particles of Spirit of Nitre enter the pores of white paper, they make it stiff and friable. This may be seen if one pours a few drops into a small iron receptacle (A) which is at white heat and the smoke is channelled through a paper covering (B). Moreover, Spirit of Nitre softens leather, but does not make it moist; on the contrary, it shrinks it, as also does fire.

Same section. “Since Nature has designed them both for flying and for swimming….” He seeks the cause from purpose.

Section 23. “… though their motion is rarely perceived by us. Take then … etc.” Without this experiment and without going to any trouble, the thing is sufficiently evident from the fact that our breath, which in winter is obviously seen to be in motion, nevertheless cannot be seen so in summer, or in a heated room. Furthermore, if in summer the breeze suddenly cools, the vapours rising from water, since by reason of the change in the density of the air they cannot disperse through it as readily as they did before it cooled, gather again over the surface of the water in such quantity that they can easily be seen by us. Again, movement is often too gradual to be observed by us, as we can gather in the case of a sundial and the shadow cast by the sun; and it is frequently too swift to be observed by us, as can be seen in the case of an ignited piece of tinder when it is moved in a circle at some speed; for then we imagine the ignited part to be at rest at all points of the circle which it describes in its motion. I would here give the reasons for this, did I not judge it superfluous. Finally, let me say in passing that, to understand the nature of fluid in general, it is sufficient to know that we can move our hand in any direction without any resistance, the motion being proportionate to the fluid. This is quite obvious to those who give sufficient attention to those notions that explain Nature as it is in itself, not as it is related to human senses. Not that I therefore dismiss this piece of research as pointless. On the contrary, if in the case of every liquid such research were done with the greatest possible accuracy and reliability, I would consider it most useful for understanding their individual differences, a result much to be desired by all philosophers as being very necessary.

On Solidity

Section 7. “… (it seems consonant) to the universal laws of Nature….” This is Descartes’ demonstration, and I do not see that the esteemed author produces any original demonstration deriving from his experiments or observations.

I had made many notes here and in what follows, but later I saw that the esteemed author had corrected himself.

Section 15. “… and once four hundred and thirty-two (ounces) …”26 If one compares it with the weight of quicksilver enclosed in the tube, it comes very near to the true weight. But I would consider it worthwhile to examine this, so as to obtain, as far as possible, the ratio between the lateral or horizontal pressure of air and the perpendicular pressure. I think it can be done in this way:

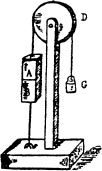

Let CD in figure 1 be a flat mirror thoroughly smoothed, and AB two pieces of marble directly touching each other. Let the marble piece A be attached to a hook E, and B to a cord N. T is a pulley, and G a weight which will show the force required to pull marble B away from marble A in a horizontal direction.

In figure 2, let F be a sufficiently strong silk thread by which marble B is attached to the floor, D a pulley, G a weight which will show the force required to pull marble A from marble B in a perpendicular direction.27 It is not necessary to go into this at greater length.

Here you have, my good friend, what I have so far found worthy of note in regard to Mr. Boyle’s experiments. As to your first queries, when I look through my replies to them I do not see that I have omitted anything. And if perchance I have put something obscurely (as I often do through lack of vocabulary), please be good enough to point it out to me. I shall take pains to explain it more clearly.

As to the new question you raise, to wit, how things began to be and by what bond they depend on the first cause, I have written a complete short work on this subject, and also on the emendation of the intellect,28 and I am engaged in transcribing and correcting it. But sometimes I put the work aside, because I do not as yet have any definite plan for its publication. I am naturally afraid that the theologians of our time may take offence, and, with their customary spleen, may attack me, who utterly dread brawling. I shall look for your advice in this matter, and, to let you know the contents of this work of mine which may ruffle the preachers, I tell you that many attributes which are attributed to God by them and by all whom I know of, I regard as belonging to creation. Conversely, other attributes which they, because of their prejudices, consider to belong to creation, I contend are attributes of God which they have failed to understand. Again, I do not differentiate between God and Nature in the way all those known to me have done. I therefore look to your advice, for I regard you as a most loyal friend whose good faith it would be wrong to doubt. Meanwhile, farewell, and, as you have begun, so continue to love me, who am,

Yours entirely,

Benedict Spinoza

[Known only from the O.P. The original is lost. The letter is undated, but a conjectural date is late in July 1662.]

It is many weeks ago, esteemed Sir, that I received your very welcome letter with its learned comments on Boyle’s book. The author himself joins with me in thanking you most warmly for the thoughts you have shared with us, and would have indicated this more quickly had he not entertained the hope that he might soon be relieved of the quantity of business with which he is burdened so that he could have sent you his reply along with his thanks at the same time. However, so far he finds himself disappointed of this hope, being so pressed by both public and private business that at present he can do no more than convey his gratitude to you, and is compelled to defer to another time his opinion on your comments. Furthermore, two opponents have attacked him in print, and he thinks himself bound to reply to them at the first opportunity. These writings are directed not against his Essay on Nitre but against another book of his containing his Pneumatic Experiments,29 proving the elasticity of air. As soon as he has extricated himself from these labours he will also disclose to you his thoughts on your objections. Meanwhile he asks you not to take amiss this delay.

The College of Philosophers of which I spoke to you has now, by our King’s grace, been converted into a Royal Society and presented with the public charter30 whereby it is granted special privileges, and there is a very good prospect that it will be endowed with the necessary funds.

I would by all means urge you not to begrudge scholars the learned fruits of your acute understanding both in philosophy and theology, but to let them be published despite the growlings of pseudo-theologians. Your republic is quite free, and in it philosophy should be pursued quite freely; but your own prudence will suggest to you that you express your ideas and opinions as moderately as you can, and for the rest leave the outcome to fate.

Come, then, excellent Sir, away with all fear of stirring up the pygmies of our time. Long enough have we propitiated ignorance and nonsense. Let us spread the sails of true knowledge and search more deeply than ever before into Nature’s mysteries. Your reflections, I imagine, can be printed in your country with impunity, and there is no need to fear that they will give any offence to the wise. If you find such to be your patrons and supporters (as I am quite sure that you will find them), why should you dread an ignorant Momus? I will not let you go, honoured friend, until I have prevailed on you, and never will I permit, as far as in me lies, that your thoughts, which are of such importance, should be buried in eternal silence. I urgently request you to be good enough to let me know, as soon as you conveniently can, what are your intentions in this matter.

Perhaps things will be happening here not unworthy of your notice. The aforementioned Society will now more vigorously pursue its purpose, and maybe, provided that peace lasts in these shores, it will grace the Republic of Letters with distinction. Farewell, distinguished Sir, and believe me to be,

Your very devoted and dear friend,

Henry Oldenburg

[Printed in the O.P. The original is extant. There are certain omissions in the O.P. text.]

Most upright friend,

I have long wished to pay you a visit, but the weather and the hard winter have not favoured me. Sometimes I bewail my lot, in that the distance between us keeps us so far apart from one another. Fortunate, yes, most fortunate is your companion Casuarius31 who dwells beneath the same roof, and can converse with you on the highest matters at breakfast, at dinner, and on your walks. But although we are physically so far apart, you have frequently been present in my thoughts, especially when I am immersed in your writings and hold them in my hand. But since not everything is quite clear to the members of our group (which is why we have resumed our meetings), and in order that you may not think that I have forgotten you, I have set myself to write this letter.

As for our group, our procedure is as follows. One member (each has his turn) does the reading, explains how he understands it, and goes on to a complete demonstration, following the sequence and order of your propositions. Then if it should happen that we cannot satisfy one another, we have deemed it worthwhile to make a note of it and to write to you so that, if possible, it should be made clearer to us and we may, under your guidance, uphold truth against those who are religious and Christian in a superstitious way, and may stand firm against the onslaught of the whole world.

So, when the definitions did not all seem clear to us on our first reading and explaining them, we were not in agreement as to the nature of definition. In this situation, in your absence, we consulted a certain author, a mathematician named Borelli.32 In his discussion of the nature of definition, axiom and postulate, he also cites the opinions of others on this subject. His own opinion goes as follows: “Definitions are employed in a proof as premisses. So they must be quite clearly known; otherwise knowledge that is scientific or absolutely certain cannot be acquired from them.” In another place he writes: “In the case of any subject, the principle of its structure, or its prime and best known essential feature, must be chosen not at random but with the greatest care. For if the construction and feature named is impossible, then the result will not be a scientific definition. For instance, if one were to say, ‘Let two straight lines enclosing a space be called figurals’, the definitions would be of non-entities, and would be impossible. Therefore from these it is ignorance, not knowledge, that would be deduced. Again, if the construction or feature named is indeed possible and true, but unknown to us or doubtful, then the definition will not be sound. For conclusions that derive from what is unknown and doubtful are also uncertain and doubtful, and therefore afford us mere conjecture or opinion, and not sure knowledge.”

Tacquet33 seems to disagree with this view; he asserts, as you know, that it is possible to proceed directly from a false proposition to a true conclusion. Clavius,34 whose view he (Borelli) also introduces, thinks as follows: “Definitions are arbitrary terms, and there is no need to give the grounds for choosing that a thing should be defined in this way or that. It is sufficient that the thing defined should never be asserted to agree with anything unless it is first proved that the given definition agrees with that same thing.” So Borelli maintains that the definition of any subject must consist of a feature or structure which is prime, essential, best known to us, and true, whereas Clavius holds that it matters not whether it be prime, or best known, or true or not, as long as it is not asserted that the definition we have given agrees with some thing unless it is first provided that the given definition agrees with that same thing. We are inclined to favour Borelli’s view, but we are not sure whether you, Sir, agree with either or neither. Therefore, with such various conflicting views being advanced on the nature of definition—which is accounted as one of the principles of demonstration—and since the mind, if not freed from difficulties surrounding definition, will be in like difficulty regarding deductions made from it, we would very much like you, Sir, to write to us (if we are not giving you too much trouble and your time allows) giving your opinion on the matter, and also on the difference between axioms and definitions. Borelli admits no real distinction other than the name; you, I believe, maintain that there is another difference.

Next, the third Definition35 is not sufficiently clear to us. I brought forward as an example what you, Sir, said to me at the Hague, to wit, that a thing can be considered in two ways: either as it is in itself, or in relation to another thing. For instance, the intellect; for it can be considered either under Thought or as consisting of ideas. But we do not quite see what difference could be here. For we consider that, if we rightly conceive Thought, we ought to comprehend it under ideas, because with the removal of all ideas we would destroy Thought. So the example not being sufficiently clear to us, the matter still remains somewhat obscure, and we stand in need of further explanation.

Finally, at the beginning of the third Scholium to Proposition 8,36 we read: “Hence it is clear that, although two attributes may be conceived as really distinct (that is, the one without the aid of the other), it does not follow that they constitute two entities or two different substances. The reason is that it is of the nature of substance that all its attributes—each one individually—are conceived through themselves, since they have been in it simultaneously.” In this way you seem, Sir, to suppose that the nature of substance is so constituted that it can have several attributes, which you have not yet proved, unless you are referring to the fifth definition37 of absolutely infinite substance or God. Otherwise, if I were to say that each substance has only one attribute, I could rightly conclude that where there are two different attributes there are two different substances. We would ask you for a clearer explanation of this.

Next, I am most grateful for your writings which were conveyed to me by P. Balling and gave me great pleasure, particularly the Scholium to Proposition 19.38 If I can here serve you, too, in any way which is within my power, I am yours to command. You need only let me know. I have begun a course of anatomy, and am about half way through. When it is completed, I shall begin chemistry, and thus following your advice I shall go through the whole medical course. I must stop now, and await your reply. Accept my greetings, who am,

Your very devoted,

S. J. D’Vries

1663. Given at the Hague, 24 February

To Mr. Benedict Spinoza, at Rijnsburg

[Printed in the O.P. The original is extant. The O.P. text is an abridged version of the original, and the last paragraph appears only in the Dutch edition of the O.P. The letter is undated. A conjectural date is February 1663.]

My worthy friend,

I have received your letter, long looked for, for which, and for your cordial feelings towards me, accept my warmest thanks. Your long absence has been no less regretted by me than by you, but at any rate I am glad that my late-night studies are of use to you and our friends, for in this way I talk with you while we are apart. There is no reason for you to envy Casearius. Indeed, there is no one who is more of a trouble to me, and no one with whom I have had to be more on my guard. So I should like you and all our acquaintances not to communicate my opinions to him until he will have reached a more mature age. As yet he is too boyish, unstable, and eager for novelty rather than for truth. Still, I am hopeful that he will correct these youthful faults in a few years time. Indeed, as far as I can judge from his character, I am reasonably sure of this; and so his nature wins my affection.

As to the questions raised in your group (which is sensibly organised), I see that your difficulties result from your failure to distinguish between the kinds of definition. There is the definition that serves to explicate a thing whose essence alone is in question and the subject of doubt, and there is the definition which is put forward simply for examination. The former, since it has a determinate object, must be a true definition, while this need not be so in the latter case. For example, if someone were to ask me for a description of Solomon’s temple, I ought to give him a true description, unless I propose to talk nonsense with him. But if I have in my own mind formed the design of a temple that I want to build, and from its description I conclude that I will have to purchase such-and-such a site and so many thousands of stones and other materials, will any sane person tell me that I have reached a wrong conclusion because my definition may be incorrect? Or will anyone demand that I prove my definition? Such a person would simply be telling me that I had not conceived that which in fact I had conceived, or he would be requiring me to prove that I had conceived that which I had conceived, which is utter nonsense. Therefore a definition either explicates a thing as it exists outside the intellect—and then it should be a true definition, differing from a proposition or axiom only in that the former is concerned only with the essences of things or the essences of the affections of things, whereas the latter has a wider scope, extending also to eternal truths—or it explicates a thing as it is conceived by us, or can be conceived. And in that case it also differs from an axiom and proposition in requiring merely that it be conceived, not conceived as true, as in the case of an axiom. So then a bad definition is one which is not conceived.

To make this clearer, I shall take Borelli’s example of a man who says that two straight lines enclosing an area are to be called figurals. If he means by a straight line what everybody else means by a curved line, his definition is quite sound (for the figure intended by the definition would be [as shown] or some such figure), provided that he does not at a later stage mean a square or any other such figure. But if by a straight line he means what we all mean, the thing is plainly inconceivable, and so there is no definition. All these considerations are confused by Borelli, whose view you are too much inclined to embrace.

Here is another example, the one which you adduce towards the end of your letter. If I say that each substance has only one attribute, this is mere assertion unsupported by proof. But if I say that by substance I mean that which consists of only one attribute, this is a sound definition, provided that entities consisting of more than one attribute are thereafter given a name other than substance.

In saying that I do not prove that a substance (or an entity) can have more than one attribute, it may be that you have not given sufficient attention to the proofs. I advanced two proofs, the first of which is as follows: It is clear beyond all doubt that every entity is conceived by us under some attribute, and the more reality or being an entity has, the more attributes are to be attributed to it. Hence an absolutely infinite entity must be defined … and so on. A second proof—and this proof I take to be decisive—states that the more attributes I attribute to any entity, the more existence I am bound to attribute to it; that is, the more I conceive it as truly existent. The exact contrary would be the case if I had imagined a chimera or something of the sort.

As to your saying that you do not conceive thought otherwise than under ideas because thought vanishes with the removal of ideas, I believe that you experience this because when you, as a thinking thing, do as you say, you are banishing all your thoughts and conceptions. So it is not surprising that when you have banished all your thoughts, there is nothing left for you to think. But as to the point at issue, I think I have demonstrated with sufficient clarity and certainty that the intellect, even though infinite, belongs to Natura naturata, not to Natura naturans.39

Furthermore, I fail to see what this has to do with understanding the Third Definition,40 or why this definition causes you difficulty. The definition as I gave it to you runs, if I am not mistaken, “By substance I understand that which is in itself and is conceived through itself; that is, that whose conception does not involve the conception of another thing. I understand the same by attribute, except that attribute is so called in respect to the intellect, which attributes to substance a certain specific kind of nature.” This definition, I repeat, explains clearly what I mean by substance or attribute. However, you want me to explain by example—though it is not at all necessary—how one and the same thing can be signified by two names. Not to appear ungenerous, I will give you two examples. First, by ‘Israel’ I mean the third patriarch: by ‘Jacob’ I mean that same person, the latter name being given to him because he seized his brother’s heel.41 Secondly, by a ‘plane surface’ I mean one that reflects all rays of light without any change. I mean the same by ‘white surface’, except that it is called white in respect of a man looking at it.

With this I think that I have fully answered your questions. Meanwhile I shall wait to hear your judgment. And if there is anything else which you consider to be not well or clearly enough explained, do not hesitate to point it out to me, etc.

[Known only from the O.P. The original is lost. Undated. A conjectural date is March 1663.]

My worthy friend,

You ask me whether we need experience to know whether the definition of some attribute be true. To this I reply that we need experience only in the case of those things that cannot be deduced from the definition of a thing, as, for instance, the existence of modes; for this cannot be deduced from a thing’s definition. We do not need experience in the case of those things whose existence is not distinguished from their essence and is therefore deduced from their definition. Indeed, no experience will ever be able to tell us this, for experience does not teach us the essences of things. The most it can do is to determine our minds to think only about the certain essences of things. So since the existence of attributes does not differ from their essence, we shall not be able to apprehend it by any experience.

As to your further question as to whether things or the affections of things are also eternal truths, I say, most certainly. If you go on to ask why I do not call them eternal truths, I reply, in order to mark a distinction, universally accepted, between these and the truths which do not explicate a thing or the affection of a thing, as, for instance, ‘nothing comes from nothing’. This and similar propositions, I say, are called eternal truths in an absolute sense, by which title is meant simply that they do not have any place outside the mind, etc.

[Known only from the O.P. The original is lost.]

Excellent Sir and dear friend,

I could produce many excuses for my long silence, but I shall reduce my reasons to two: the illness of the illustrious Mr. Boyle and the pressures of my own business. The former has prevented Boyle from replying to your Observations on Nitre at an earlier date; the latter have kept me so busy over several months that I have scarcely been my own master, and so I have been unable to discharge the duty which I declare I owe you. I rejoice that, for the time at least, both obstacles are removed, so that I can resume my correspondence with so close a friend. This I now do with the greatest pleasure, and I am resolved, with Heaven’s help, to do everything to ensure that our epistolary intercourse shall never in future suffer so long an interruption.

Before I deal with matters what concern just you and me alone, let me deliver what is due to you on Mr. Boyle’s account. The observations which you composed on his short Chemical-Physical Treatise he has received with his customary good nature, and sends you his warmest thanks for your criticism. But first he wants you to know that it was not his intention to demonstrate that this is a truly philosophical and complete analysis of Nitre, but rather to make the point that the common doctrine of Substantial Forms and Qualities accepted in the Schools rests on a weak foundation, and that what they call the specific differences of things can be reduced to the magnitude, motion, rest and position of the parts.

With this preliminary remark, our Author goes on to say that his experiment with Nitre shows quite clearly that through chemical analysis the whole body of Nitre was resolved into parts which differed from one another and from the original whole, and that afterwards it was so reconstituted and redintegrated from these same parts that it lacked little of its original weight. He adds that he has shown this to be a fact, but he has not been concerned with the way in which it comes about, which seems to be the subject of your conjectures, and that he has reached no conclusion on that matter, since that went beyond his purpose. However, as to what you suppose to be the way in which it comes about, and your view that the fixed salt of Nitre is its dregs and other such theories, he considers that these are merely unproved speculations. And as to your idea that these dregs, or this fixed salt, has openings hollowed out to the size of the particles of Nitre, on this subject our Author points out that salt of potash combined with Spirit of Nitre constitutes Nitre just as well as Spirit of Nitre combined with its own fixed salt. Hence he thinks it clear that similar pores are to be found in bodies of that kind, from which nitrous spirits are not given off. Nor does the Author see that the necessity for the very fine matter, which you allege, is proved from any of the phenomena, but he says it is assumed simply from the hypothesis of the impossibility of a vacuum.

The Author says that your remarks on the causes of the difference of taste between Spirit of Nitre and Nitre do not affect him; and as to what you say about the inflammability of Nitre and the non-inflammability of Spirit of Nitre, he says that this presupposes Descartes’ theory of fire,42 with which he declares he is not yet satisfied.

With regard to the experiments which you think confirm your explanation of the phenomenon, the Author replies that (1) Spirit of Nitre is indeed Nitre in respect of its matter, but not in respect of its form, since they are vastly different in their qualities and properties, viz. in taste, smell, volatility, power of dissolving metals, changing the colours of vegetables, etc. (2) When you say that some particles carried upwards coalesce into crystals of Nitre, he maintains that this happens because the nitrous parts are driven off through the fire along with Spirit of Nitre, as is the case with soot. (3) As to your point about the effect of purification, the Author replies that through that purification the Nitre is for the most part freed from a certain salt which resembles common salt, and that its ascending to form icicles is something it has in common with other salts, and depends on air pressure and other causes which must be discussed elsewhere and have no bearing on the present question. (4) With regard to your remarks on your third experiment, the Author says that the same thing occurs with certain other salts. He asserts that when the paper is actually alight, it sets in motion the rigid and solid particles composing the salt and in this way causes them to sparkle.

Next, when you think that in the fifth section the noble Author is criticising Descartes, he believes that you yourself are here at fault. He says that he was in no way referring to Descartes, but to Gassendi and others who attribute to Nitre a cylindrical shape when it is in fact prismatic, and that he is speaking only of visible shapes.

To your comments on sections 13–18, he merely replies that he wrote these sections with this main object, to demonstrate and assert the usefulness of chemistry in confirming the mechanical principles of philosophy, and that he has not found these matters so clearly conveyed and treated by others. Our Boyle belongs to the class of those who do not have so much trust in their reason as not to want phenomena to agree with reason. Moreover, he says that there is a considerable difference between superficial experiments where we do not know what Nature contributes and what other factors intervene, and those experiments where it is established with certainty what are the factors concerned. Pieces of wood are much more composite bodies than the subject dealt with by the Author. And in the case of ordinary boiling water fire is an additional external factor, which is not so in the production of our sound. Again, the reason why green vegetation changes into so many different colours is still being sought, but that this is due to the change of the parts is established by this experiment, which shows that the change of colour was due to the addition of Spirit of Nitre. Finally, he says that Nitre has neither a foul nor a sweet smell; it acquires a foul smell simply as a result of its decomposition, and loses it when it is recompounded.

With regard to your comments on section 25 (the rest, he says, does not touch him) he replies that he has made use of the Epicurean principles which hold that there is an innate motion in particles; for he needed to make use of some hypothesis to explain the phenomenon. Still, he does not on that account adopt it as his own, but he uses it to support his view against the chemists and the Schools, demonstrating merely that the facts can be well explained on the basis of the said hypothesis. As to your additional remark at the same place on the inability of pure water to dissolve the fixed parts, our Boyle replies that it is the general opinion of chemists from their observations that pure water dissolves alkaline salts more rapidly than others.

The Author has not yet had time to consider your comments on fluidity and solidity. I am sending you what I here enclose so that I may not any longer be deprived of intercourse and correspondence with you. But I do most earnestly beg you to take in good part what I here pass on to you in such a disjointed and disconnected way, and to ascribe this to my haste rather than to the character of the illustrious Boyle. For I have assembled these comments as a result of informal talk with him on this subject rather than from any deliberate and methodical reply on his part. Consequently, many things which he said have doubtless escaped me, which were perhaps more substantial and better expressed than what I have here set down. All blame, therefore, I take on my own shoulders, and entirely absolve the Author.

Now I shall turn to matters that concern you and me, and here at the outset let me be permitted to ask whether you have completed that little work of such great importance, in which you treat of the origin of things and their dependence on a first cause, and also of the emendation of our intellect. Of a surety, my dear friend, I believe that nothing can be published more agreeable and more welcome to men who are truly learned and wise than a treatise of that kind. That is what a man of your talent and character should look to, rather than what pleases the theologians of our age and fashion. They look not so much to truth as to what suits them. So I urge you by our bond of friendship, by all the duties we have to promote and disseminate truth, not to begrudge or deny us your writings on these subjects. If, however, there is some consideration of greater weight than I can foresee which holds you back from publishing the work, I heartily beg you to be pleased to let me have by letter a summary of it, and for this service you will find me a grateful friend. There will soon be more publications43 from the learned Boyle which I shall send you by way of requital, adding an account of the entire constitution of our Royal Society, of whose Council I am a member with twenty others, and joint secretary with one other. At present lack of time prevents me from going on to other matters. To you I pledge all the loyalty that can come from an honest heart, and an entire readiness to do you any service that lies within my slender powers, and I am, sincerely,

Excellent Sir, yours entirely,

Henry Oldenburg

London, 3 April 1663

[Printed in the O.P. The original is lost, but a copy made by Leibniz has been preserved.]

Dearest friend,

I have received two letters from you, one dated January 11 and delivered to me by our friend N.N.,44 the other dated March 26 and sent to me by an unknown friend from Leiden. They were both very welcome, especially as I gathered from them that all is well with you and that I am often in your thoughts. My most cordial thanks are due to you for the kindness and esteem you have always seen fit to show me. At the same time I beg you to believe that I am no less your devoted friend, and this I shall endeavour to prove whenever the occasion arises, as far as my slender abilities allow. As a first offering, I shall try to answer the request made to me in your letters, in which you ask me to let you have my considered views on the question of the infinite. I am glad to oblige.

The question of the infinite has universally been found to be very difficult, indeed, insoluble, through failure to distinguish between that which must be infinite by its very nature or by virtue of its definition, and that which is unlimited not by virtue of its essence but by virtue of its cause. Then again, there is the failure to distinguish between that which is called infinite because it is unlimited, and that whose parts cannot be equated with or explicated by any number, although we may know its maximum or minimum. Lastly, there is the failure to distinguish between that which we can apprehend only by the intellect and not by the imagination, and that which can also be apprehended by the imagination. I repeat, if men had paid careful attention to these distinctions, they would never have found themselves overwhelmed by such a throng of difficulties. They would clearly have understood what kind of infinite cannot be divided into, or possess any, parts, and what kind can be so divided without contradiction. Again, they would also have understood what kind of infinite can be conceived, without illogicality, as greater than another infinite, and what kind cannot be so conceived. This will become clear from what I am about to say. However, I shall first briefly explain these four terms: Substance, Mode, Eternity, Duration.

The points to be noted about Substance are as follows. First, existence pertains to its essence; that is, solely from its essence and definition it follows that Substance exists. This point, if my memory does not deceive me, I have proved to you in an earlier conversation without the help of any other propositions. Second, following from the first point, Substance is not manifold; rather there exists only one Substance of the same nature. Thirdly, no Substance can be conceived as other than infinite.45

The affections of Substance I call Modes. The definition of Modes, insofar as it is not itself a definition of Substance, cannot involve existence. Therefore, even when they exist, we can conceive them as not existing. From this it further follows that when we have regard only to the essence of Modes and not to the order of Nature as a whole, we cannot deduce from their present existence that they will or will not exist in the future or that they did or did not exist in the past. Hence it is clear that we conceive the existence of Substance as of an entirely different kind from the existence of Modes. This is the source of the difference between Eternity and Duration. It is to the existence of Modes alone that we can apply the term Duration; the corresponding term for the existence of Substance is Eternity, that is, the infinite enjoyment of existence or—pardon the Latin—of being (essendi).

What I have said makes it quite clear that when we have regard only to the essence of Modes and not to Nature’s order, as is most often the case, we can arbitrarily delimit the existence and duration of Modes without thereby impairing to any extent our conception of them; and we can conceive this duration as greater or less, and divisible into parts. But Eternity and Substance, being conceivable only as infinite, cannot be thus treated without annulling our conception of them. So it is nonsense, bordering on madness, to hold that extended Substance is composed of parts or bodies really distinct from one another. It is as if, by simply adding circle to circle and piling one on top of another, one were to attempt to construct a square or a triangle or any other figure of a completely different nature. Therefore the whole conglomeration of arguments whereby philosophers commonly strive to prove that extended Substance is finite collapses of its own accord. All such arguments assume that corporeal Substance is made up of parts. A parallel case is presented by those who, having convinced themselves that a line is made up of points,46 have devised many arguments to prove that a line is not infinitely divisible.

However, if you ask why we have such a strong natural tendency to divide extended Substance, I answer that we conceive quantity in two ways: abstractly or superficially, as we have it in the imagination with the help of the senses, or as Substance, apprehended solely by means of the intellect. So if we have regard to quantity as it exists in the imagination (and this is what we most frequently and readily do), it will be found to be divisible, finite, composed of parts, and manifold. But if we have regard to it as it is in the intellect and we apprehend the thing as it is in itself (and this is very difficult), then it is found to be infinite, indivisible, and one alone, as I have already sufficiently proved.