CHAPTER 7

A PASSPORT INTO THE WORLD OF WOMEN

SOMETIME IN 1952, Harold Gillies cleared off a table in his consulting office, placing a bust of Rudolf Virchow, the father of modern pathology, off to the side. He lifted the torso of a male corpse onto the empty table. Then, smoking furiously, he began to practice for the next day's surgery on Roberta Cowell. Gillies slipped the sleeve of skin off the corpse's penis and discarded the contents of the organ, leaving a large flap of skin. Shaping that skin around one of his fingers, he formed it into an envelope that would fit into a cavity he had already cut in the torso's groin, creating a vagina. The trick appeared to work. Tomorrow, he would perform the first vaginal construction that had ever been attempted in Britain.1 "This was the big one," according to Ralph Millard, the American surgeon who assisted Gillies.2 Because there was almost no medical literature on male-to-female sex-change operations, Gillies would have to extemporize.

Of course, Roberta Cowell's anatomy did not exactly match that of the corpse's: she had already had her testicles removed. The American surgeon, Millard, confirmed this fact—when he examined Cowell, he says, it was obvious that her testicles had been surgically removed, though he did not know how or where that operation had occurred.3

While Gillies and Millard labored in a back room, doing a dry run of the surgery on a dead man, Roberta Cowell entered the clinic from the front. She checked in wearing a skirt and a blond wig. The nurses showed her to her room. She lay on the bed, tossing and turning, her heart pounding. "I was scared stiff. I was off on an unknown road to an unknown future . . . The operation might not succeed . . . I might be desperately uncomfortable afterwards; I might be in great pain. Perhaps the story would leak out, and life afterwards would be impossible."4

Two days later, she woke from a drugged haze. Her hands were swollen and covered with bruises from the anesthesia the doctors had pumped into her. Bandages hid the bottom half of her torso. When Gillies came in to remove the catheter, he announced that the operation had been a success: she had a vagina. After all her worries, it had been that easy. She recovered and checked out.

But soon, Cowell decided the vagina was not enough; to be truly female, she would need a new face. She could not bear to be stuck with Robert Cowell's profile—he had been another person entirely. He'd had a perfectly serviceable male nose, but it wouldn't do for a gamine. She went back to Gillies for a button nose, "slightly retrousse," as she put it.5 Also, fuller lips. Cosmetic surgery on the face, in those days, remained a rarity. The ordinary girl still resigned herself to a wide nose or a birthmark. But Cowell was no ordinary girl. She emerged from Gillies's treatments with a turned-up, flirty little nose and a big film-star mouth that seemed to be made for scarlet lipstick.

Men swarmed as she tottered down the street on her high heels. They rubbernecked as she strutted past them. They slowed down in cars to ask her directions—and then wanted to go out to dinner with her. They bumped into her, then offered to buy her a drink by way of apology. Those with manners dashed up to her on the street and said, "Excuse me, I know it's very rude to speak to you, but isn't it a nice day?"6

She worked hard that first year at being a woman, learning to cook, to apply makeup, to strut on high heels, and to snatch a hand off her knee. It was as if, she wrote, "each new thing I learned [was] another visa stamped in the passport I needed for entry into the world of womankind."7

She had given up her passport into the world of men. That had cost her dearly—thousands upon thousands of pounds. In 1952, Cowell had to dissolve the company that she'd founded years before, in the hopes of designing an Aspin engine to showcase at the Grand Prix. Cowell did not dare risk calling attention to herself by competing in one of the world's top races. "The possibility of publicity came up and I voluntarily liquidated the [engine-design] company and lost all the money," she wrote. Cowell would never design a winning engine or race in a major event again.8

Michael Dillon had graduated from one of the best medical schools in Ireland, but in 1951 he accepted a yearlong residency that paid only one pound a week. For that small sum, Dillon would act as surgeon, specialist, and house doctor in a fifty-bed hospital in the north of Dublin.

With his modest inheritance, he might have waited for something better to come along. Still, this was the only job he'd managed to get right away, and Dillon was eager to keep himself busy and forget Roberta Cowell. He took the position. That year, in a frenzy of altruism, he organized teas and trips to the theater for his patients, founded a lending library inside the hospital, and raised money to install radios and headphones beside every bed so that patients could listen to music.

Dillon's charges stirred in him a new and powerful empathy, particularly an orphan boy named Johnny. The boy had arrived at the hospital at age fifteen; now, three years later, with his TB in remission, he was free to leave. When it came time to discharge Johnny, however, Dillon discovered the boy had only two possessions to his name: a ballpoint pen and a pair of shoes that he'd outgrown. Johnny did not even have a suit of street clothes to wear out the door. Or a place to go.

That night, after he'd discovered Johnny's predicament, Dillon returned to his little house and surveyed all his possessions: the silver rowing cups on the mantel, the leather chairs, the side table with whiskey set out on it, and the closet full of suits. His belongings—not particularly lavish, to be sure—struck him as obscene. "How could one own all these things when there was a boy with absolutely nothing?" he asked himself.9 Dillon was so shaken by Johnny's poverty that he vowed to give up one tenth of his earnings to charity—a promise that he would keep, and then some.

In February 1953, Christine Jorgensen landed at Idle wild Airport (now JFK Airport) after enduring a series of treatments in Copenhagen that had transformed her from a skinny, jug-eared boy into a blond debutante with a grin of pearls at her neck. Gathering her fur coat, Jorgensen ducked through the door of the plane and was confronted with the evidence of her fame. Three hundred reporters fought to get closer, yelling at her, popping flashbulbs. "Where did you get the fur coat?" "How about a cheesecake shot, Christine?" "Do you expect to marry?"10

And so, Christine Jorgensen became known as the "first" transsexual—though she was certainly not the first to go through a sex-change operation or to use hormones to transform her body.

"I clutched my belongings more closely to me," she wrote about that moment when she surveyed the reporters below her. "[I] stumbled slightly as I reached out to grasp a handrail, and started slowly down the landing stairs . . . At that moment, I was descending into a new and alien world."11

That year, she would become the number one news story in America, EX-GI BECOMES BLONDE BEAUTY, MDS RULE CHRIS 100 PERCENT WOMAN. DISILLUSIONED CHRISTINE TO BECOME MAN AGAIN!! I'VE FALLEN IN LOVE WITH CHRISTINE, SAYS REPORTER. The tabloids found dozens of ways to re-spin her story. Jorgensen, with her considerable charm and wit, managed to rise above the attacks and sneers and became a sort of ambassador from the land of transsexuals, a place she portrayed as being as modern and spick-and-span as Copenhagen itself. "I knew that much of the curiosity and interest stemmed from the understandable fact that people were looking for answers," she wrote.12 Jorgensen did her best to supply those answers, plowing through the twenty thousand letters written to her and helping those she could. At the time, she was so much a phenomenon that even envelopes addressed to "Christine Jorgensen, USA" reached her.

Tabloid magazines would accuse her of fakery—they insisted she must be a woman who pretended to have a sex change, because no man could effect such a miraculous transformation. Others portrayed her as a pervert and a freak. Jorgensen countered with her own public appearances; dressed in designer gowns, she deployed a hostessy charm that put everyone at ease. The Scandinavian Society named her woman of the year. She lunched with Danny Kaye, Milton Berle, and Truman Capote. Always, she showed up with her ice-colored hair perfectly coiffed, skin glowing, lips plump and red.

Natural-born females took note. If hormones and surgery could make a biological man look that good, what might the treatments do for women? The estrogen therapy that she'd been using for years, Jorgensen claimed, had given her skin an ethereal softness and filled her with a sense of well-being. And unlike the surgical component of Jorgensen's transformation, hormones were easy to obtain. Anyone who was determined enough could find a way to buy estrogen from a drugstore. In fact Jorgensen had done just that.

In 1948, a college boy named George Jorgensen worked up the nerve to consult a top endocrinologist in Connecticut. "I came here to ask you what I can do about my feelings of being a sexual mix-up," the young man stammered. "Is it at all possible that the trouble lies in a glandular or chemical imbalance of some kind?"

The doctor refused to help; he also committed the further cruelty of keeping Jorgensen in the dark about estrogen, which was then a readily available drug. Instead, he sent Jorgensen off to a psychiatrist, and that was the end of it.

Except it wasn't. Jorgensen stumbled across Paul de Kruif 's then best seller about testosterone, The Male Hormone. He read it so many times the binding split, memorizing passages about estradiol (a variant of estrogen). Jorgensen had never heard of anyone using hormones to change sex, but he decided to see if it was possible. He wandered into a section of New Haven where he knew no one would recognize him, found a drugstore, and asked for estradiol.

"That's a pretty strong chemical," the man behind the counter warned. "We're not supposed to sell it withouts a prescription."

Jorgensen claimed to be a medical student working on a hormone experiment and walked away with a hundred tablets.13 '

After months on the pill, he began to look more androgynous, with luscious skin and small breasts, though strangers still "read" him as a boy or man. What he loved most about the pill was the way it transformed his mind and mood: it erased a sense of numbness, a fatigue, and "disturbing thoughts" that had plagued him all through his life. Estrogen had worked on his mind, he felt, in the same way it had transformed his skin: turning it plush and pink, smoothing out the blemishes. A few years later, he would disappear to Copenhagen, where he received further hormone treatments and surgery, returning to the Linked States as Christine Jorgensen—a living advertisement for the magic of technology.

Jorgensen offered a model not just for transsexuals, but also for women who longed for bigger busts and that creamy, dreamy skin. In 1953, Jorgensen's friend Gen Angelo threw a charity bridge party where Christine became the star attraction in the roomful of women. "I was bombarded with questions right and left, people wondering why she did it, asking if her hair was naturally blonde and how she got her beautiful complexion," Angelo wrote. Several women began "asking for hormone treatments to give them the same smooth complexion."14 Jorgensen's decolletage—that beautiful swell of cleavage just visible between the satin folds of her gown—would no doubt have inspired wonder, too. Breast-augmentation surgery was still rare.

In the 1950s, new technologies existed that could radically transform appearance, but these technologies were being used to their fullest effect only by a few people. Those people were transsexuals. When Christine Jorgensen stepped out of that plane in 1953, she showed America how very thin the line between male and female could be. She also announced a new age was coming. An age in which the body—any body—could be molded into the shape that the mind demanded.

Roberta Cowell's phone rang in the middle of the night. On the other end of the line, one of her boyfriends, a newspaper reporter, gushed about an incredible story he'd just heard. An American named George Jorgensen had flown to Denmark, where doctors had transformed him into a woman. Cowell's boyfriend was sure that the story must be a hoax. How could a man turn into a woman?

Cowell found it amusing that her boyfriend was so shocked by Christine. What would the newspaperman have done if he'd known he was dating a transsexual? "Poor man, he'd have a fit!" Cowell quipped.15

With Christine Jorgensen in the spotlight, it didn't take long for the tabloids to catch on to Cowell. In early 1954, she learned that her story was about to blow up in the British press. It's not clear who had tattled on her. Cowell herself may have been the one who leaked it. By the spring of 1954, she had negotiated with the Picture Post magazine to write up her confessions; she sold her story for twenty thousand pounds—what amounted to a small fortune in the 1950s—according to a rival tabloid, the Pictorial.16

Cowell needed that money badly. She owed thousands of pounds after the collapse of her engine-design firm; the Picture Post deal would help her pay off her debt and start over again. And, of course, publishing her autobiography in the tabloids would allow her to tell her version of the story first. By that time, Cowell did have her own version.

She insisted that even though Robert Cowell had fathered two children and passed his RAF physical, he had always possessed, in addition to the usual male equipment, a set of dormant ovaries hidden in his belly. The trauma of prisoner-of-war camp, she claimed, had set the ovaries into action, pumping out estrogen into Robert Cowell's body; that's why small breasts had spontaneously sprouted on his chest.

As Cowell told it, she'd never really had a sex change at all because she'd been born a hermaphrodite, a person whose body exhibited characteristics of both sexes. She'd resorted to surgery and hormones so that she would not have to live as a twrosexed person. Wasn't that a reasonable enough desire?

"After the sex change, her life was wholly dedicated to preserving the myth that she was 'really' female and had been all along," according to journalist Liz Hodgkinson. "The effort of preserving this falsehood eventually, I believe, unhinged her."17

In the last forty years, the sex-change autobiography has become a genre unto itself. Dozens of transsexuals have written up their stories, and many of these bildungsromans, with their before-and-after story lines, have become classics, most especially Jan Morris's masterfully written Conundrum.

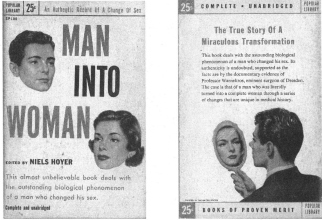

But when Roberta Cowell sat down at the typewriter to bang out her own book, she had only one model to draw on. Cowell's autobiography—serialized in the Picture Post magazine and then later released as a potboiler titled Roberta Cowell's Story—would be the first full-length sex-change memoir ever written in the English language. It would be only the second such book ever published in the world—the first had been Lili Elbe's story, which had appeared in 1932 as Ein Mensch wechselt sein Geschlecht and was translated into English a year later (as Man into Woman).

In the late 1920s, Lili Elbe had whirled through the parties and cafes of Paris, a middle-aged flapper with eyes hidden under the shadow of her sun hat, and a secret behind her demure smile. Lili had been born a man. She had resorted to every treatment she could find to make herself feminine. More specifically, she wanted to turn back the clock, so she could become a young woman. Since she lived in the era of organology, monkey-gland treatments, and X-ray miracle cures, doctors were only too eager to tease her with the possibility of such a transformation. Today, Lili is regarded as the first person to have survived a sex-change operation. But that is not how Lili herself would have described her medical odyssey. Instead, Lili regarded herself as a person who had been "rejuvenated," restored to the youth and femininity that were hallmarks of her true self.

Lili began as an artist named Einar Wegener in the early 1900s in a studio with a sweeping view of Copenhagen. Einar's wife—then a painter of some fame—had needed a female model to finish up one of her portraits. She'd pleaded with Einar to dress in drag, sit before her, and model. He had such nice legs, after all. Neither of them expected what happened next: in his wig and dress, he metamorphosed into an adorable gamine. They named her Lili. After Einar pulled on his trousers again, she vanished—but her presence still thrummed between them.

For years, Lili remained a kind of party game or performance-art piece; when life turned a little dull, Einar's wife would coax Lili out for the evening to accompany her to balls and picnics and cafes. The next morning Lili would disappear, dissolving back into Einar Wegener again.

For one entire year while the couple traveled, they more or less forgot about Lili. But then, when Gerda, Einar's wife, settled down to work again, frowning at the easel in concentration, she found she couldn't do without the French girl. Lili had become her muse. So once again, they summoned her, that laughing sprite who gamboled around the studio. A series of portraits resulted: Lili peered out of canvas after canvas, pouting in furs, her face as iconic and sphinxlike as any art deco beauty's. For over a decade, Lili lived that way, in fits and starts, mostly on the wall, her face frozen. And then sometime in the 1920s, the game turned desperately serious. Einar Wegener felt his own self slipping away and Lili's taking over.

Stuck in a middle-aged male body, Wegener wrote, "I seemed to myself like a deceiver, like a usurper who reigned over a body which had ceased to be his, like a person who owned merely the facade of his house."18 Another, truer self lived inside him—the French girl. For her to come to life, Wegener would have to cross two lines: he would have to reverse both his age and his sex.

He traipsed from doctor to doctor seeking a cure: could they do anything to extinguish him and bring Lili into being? Doctors who examined Wegener described his body as that of an ordinary male—not so well endowed perhaps, but ordinary. Still with no concept of transsexuality to draw on, the top medical men of the day decided that Wegener's urges must come from somewhere inside the body. So they agreed he must have ovaries hidden under his flat belly.

Doctors did not have much to offer Wegener besides the hope that he might have been a woman all along—the first doctor he saw suggested that ovaries had been lurking inside Wegener ever since he was born; they were damaged or perhaps stunted organs, not strong enough to pump out the hormones that would make his body look both female and young. Wegener's doctor had not actually seen the ovaries, but he zapped the patient's belly with X-rays anyway, to "stimulate" them.

The treatment did no good. It's likely, of course, that Wegener had no ovaries at all—that his femaleness could not be located in his abdomen, nor anywhere in the flesh. But the doctors of the time—and Wegener himself—thought the personality of Lili must have sprung out of ovarian tissue. In the 1920s, the idea that maleness or femaleness could originate in our brains—rather than our genitals—would not have occurred to any doctor. Even Hirschfeld, the Berlin sexologist who was so ahead of his time, believed that the urge to cross-dress must have something to do with the glands. Since Einar Wegener felt he was turning into a young woman, his doctors believed that ovaries—hidden somewhere inside his body—must be creating his urges.

After X-rays failed to help, Wegener consulted with one of the top German gynecologists of the day.. The doctor said exactly what Wegener wanted to hear: the withered, damaged ovaries could be replaced with new ones from a vibrant young woman. A pair of healthy ovaries, the gynecologist confirmed, would turn Wegener into Lili, once and for all.

At that time, human ovaries could be bought on the black market; a few daring older women, desperately seeking rejuvenation, had already put themselves under the knife, swapping old ovaries for new ones.19 In the era before estrogen became available as a drug, doctors knew no other way to manipulate the hormone levels in a woman's body. LInfortunately, the operation was far more likely to kill the patient than to revivify her. Surgeons simply did not have the skills to transplant ovaries and keep them working—so the organs Einar Wegener received would be so much ornamentation.

Before the patient could receive his ovaries, however, he would have to undergo another experimental procedure. A team of doctors would transform his penis into a vagina. After a preliminary operation in which he endured a castration, Einar Wegener—now7 going by the name Lili—checked into a women's clinic in Dresden, to be cared for by gynecological specialists.

For weeks, Lili recovered from her castration and waited for a new pair of ovaries—exactly how the doctors obtained those ovaries, Lili does not say. The day finally came when a nurse assured Lili that the surgeon would operate on her imminently. The ovaries had been extracted from a twenty-seven-year-old woman, the nurse said, and would pump fluids into Lili's body that would make her young again.20

The operation was a success—in that Lili lived through it. After a long recuperation, she was finally able to check out of the women's clinic; in her purse, she carried a Danish passport that declared her to be a woman—the doctors had arranged that as well. Gerda helped her to the train, and they rode side by side to Berlin: girlfriends now, sisters, best friends. All traces of Einar Wegener—aside from the paintings he'd left behind—had vanished. He was as good as dead. In fact, Lili resented any associations between herself and the parasite who had once inhabited her body. She claimed not to even share his memories. "Lili stood in front of the old house of her parents; she remembered it remotely and hazily, like something of which one had dreamed. Her brother frequently asked her if she could remember this or that incident from [their] common childhood." She could not.21

As Lili Elbe saw it, she had not changed her sex; she had had to kill off Einar to become her true self. He had been a man in his forties with an established reputation as an artist and a soulful connection to his wife; Lili, on the other hand, was a young woman, newly liberated to roam the world, struggling to find a career, eager for her first romance. While Finer had been a few years older than Gerda, Lili declared herself to be far younger, a kind of "grown-up daughter." 22 She believed that she should be allowed to change the age, as well as the sex, listed on her passport: "I find it unjust for me to retain [Einar's] age and birthday, for my biological age is quite different from his . . . [He] and 1 have really nothing whatever to do with each other," she wrote.23 Lili Elbe claimed that surgery had allowed her to overcome her body entirely: to shatter the barriers of age and sex. So why shouldn't she become a mother, too? Doctors promised her a birth canal, a uterus. Lili endured another grueling operation to achieve the final and most irrefutable proof of femininity, and in its aftermath, in 1931, she died.

Einar Wegener endured a series of groundbreaking surgeries, including the implantation of ovaries, to live as a woman. Afterward, he became Lili Elbe. The Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender and Reproduction

Unlike modern transgendered people, she had not been able to* benefit from hormone therapy, since her transplanted ovaries were useless. But she did endure one of the first surgeries, perhaps the first, to reshape a penis into a vagina. This has made her a pioneer. Now, because scholars see her as the first sex-change patient, they tend to leave out the rest. of the story: as much as Lili wanted to be female, she also wanted to be young.

While she was still transitioning, Roberta Cowell discovered a dusty, dog-eared volume of Man into Woman; Lili's story, never well known outside of Denmark, had long since been forgotten, an artifact from a more primitive medical era. Still, even though the scientific facts in the book were out-of-date, Cowell modeled her story on Einar/Lili's. She insisted she'd always had ovaries. That meant she was not an artificial woman but a real one.

The ovaries—imaginary or not—meant everything to her. "Once I realized that my femininity had & physical basis I did not despise myself so much."24 Cowell claims that a doctor discovered the ovaries—though later, she could never produce this physician nor any proof of his diagnosis. She believed she had always been female, and the estrogen treatments and plastic surgery had only helped her achieve her true biological sex.

She released a statement along these lines to the press on March 6, 1954. Almost every major British paper, aside from the London Times, ran a story about Cowell that week, most of them on page one—these stories echoed her press release, repeating her fantastical claims.25 In the United States, Newsweek cribbed from Cowell's press release: "In 1948 . . . [Robert Cowell's] mental outlook changed and his body showed female characteristics. On doctor's advice, Bob was treated with hormones to hasten the change." Roberta Cowell, the magazine reported, was now enjoying herself "somewhere in France."26

In 1952, Christine Jorgensen's sex change became a top story in U.S. newspapers. The following year, the Popular Library reissued Lili Elbe's biography from the 1930s; the publisher packaged the book in such a way that the long-ago story appeared to be breaking news. When Roberta Cowell sat down to write her own autobiography, she collected some of her outdated medical information from Lili Elbe's account.

Indeed, as Picture Post released the first installment of her story, Cowell was hiding out in Europe, prepared for the horde of journalists who would descend upon her. They chased her to Italy, a noisy, flash-popping gaggle of them. The mob staked out the villa where she'd put herself into seclusion: Cowell wouldn't talk. The Picture Post had paid for her exclusive story, which ran in seven installments, and she had nothing more to add.

Failing to get any quotes out of Cowell, reporters scoured London for anyone who would tattle on her. They hung around pubs, hoping to get a word with Cowell's old mates from race-car-driving days. They interviewed plastic surgeons and endocrinologists, anyone who might have anything to say about sex changes, to feed the public's curiosity about Cowell. She was, after all, the first Brit known to have had a sex change, and the first to come along after the Christine Jorgensen frenzy.

Roberta Cowell, fleeing from the paparazzi, stops to do some sightseeing in Italy. The photographer titled this image "Different Leanings." The Hulton Archive

Soon, with so many journalists tracking leads, Cowell's version of the story began to crumble. The Pictorial led the pack. It quoted Dr. George Dusseau, who'd signed the note that allowed Cowell to change her birth certificate. With that letter, he had not meant "to prove that Cowell had become physiologically a complete female. It was rather in the nature of a working certificate to enable the plastic surgeons to carry out their operations."27 In other words, Dusseau had done his best to put Cowell into an entirely new legal category, one so new that it didn't yet have a name. She was a man, yes, but a man who intended to transform into a woman.

Rather than a miracle of nature, the article theorized, Cowell must have been a "transvestist—a man who is compelled by an overwhelming impulse to act as a woman and feels driven to stop at nothing to bring about and encourage all possible necessary changes." The Pictorial asserted that Roberta Cowell was no woman at all—only a man who'd used surgery as a form of cross-dressing. Soon, the Pictorial dropped another shocker. Cowell's father—a prominent surgeon—confirmed that Roberta was a "transvestist." She had not been born with ovaries, according to Sir Ernest Cowell, who had, of course, examined the son when he was an infant and confirmed he was a healthy male.28

By April, one tabloid had demoted Cowell from a transvestite into a monster. "There was no physical change that called for the operations," according to an article in Sunday People. "They were done purely to meet Cowell's abnormal craving. When all this [surgical] work was complete the horror that was Robert Cowell released himself on the world as 'Roberta.' " Cowell had become a Godzilla of false femininity, a threat to the moral core of the British nation. Sunday People demanded that Cowell's birth certificate be changed back again.

When another tabloid published a photo of Roberta Cowell arching one of her shapely legs as she gave her stocking a tug, Sunday People exploded in fury: "Could there be anything more revolting than this person pretending he is a 'glamour girl' when in fact he is merely a man who has been emasculinated [sic] and who has none of the vital feminine organs? . . . Cowell should face the fact that he is now nothing but an unhappy freak."29

For a month and a half, the British tabloids gossiped furiously about Cowell. And then the frenzy burned out. Incredibly, none of the newspapers had raised questions about how Cowell had managed to obtain a castration.

One of the few people in a position to tell her secret had put himself far beyond the reach of journalists, on a ship chugging across a wide emptiness of ocean, making its way toward the holy city of Tedda. Michael Dillon was bound for Mecca.