9

Connections: build your mental blueprint

Repetition is an essential part of the accelerated learning equation, but clearly it’s not enough. In fact, there is a danger that mindless practice could interfere with your learning and even make you worse. Evidence would suggest that, up to a point, you will get better at something by simply doing it, even if you are relatively aimless in the act. But eventually there comes a level of expertise where you must strive to narrow down the pathways of excellence.

Imagine chiselling away at a huge chunk of marble with the intent of shaping a beautiful statue. At first it’s probably okay to knock off large chunks as you hone in on the general shape and size. But as you get closer to its final form you need to start being far more selective, careful, focused and patient. The tools you use become far more refined and you begin to pay more attention to small details. In much the same way, you are trying to shape and refine the pathways of your brain to exact the skills and behaviours that allow you to succeed at the highest level.

This is not just analogous of how pathways in the brain become more and more refined in line with the quality of your ‘technique’; it’s also a good metaphor for the lived experience of going through such a process. We can all relate to how much fun it must be to smash away at a marble rock with hammer and chisel, and maybe it’s this sense of fun that brings the motivation to keep coming back in the initial stages of the project. But by the time you have to start paying attention to tiny details, you might have a very different relationship with the project. Fun is still important (as you will see when we talk about resonance later) but it will inevitably be a different kind of fun.

In the same way, an entrepreneur with their own exciting start-up business may make big chunks of visible progress as they embark upon a new venture, fuelled by the excitement that comes from doing quite literally anything. From product development to branding, marketing to sales, almost every activity translates into progress when you start from ground zero. But as the venture moves further along, the shape of the business evolves and refines simultaneously, requiring much more strategic attention and finessing.

For me this is the most important of our principles of mental aptitude for one simple reason: if you form the wrong connections in the first place, then not only do you create unwanted habits and learn incorrect technique but you will also have to spend considerable time and energy unlearning these in order to progress beyond that point.

Tip for coaches

Making the right connections must be an active process driven by the athlete and supported by the coach, not a passive process for the athlete driven by the coach. If your goal is to organise and strengthen your mental process in order that you are more consistent and confident in your own mind, then you cannot have someone else do all the thinking for you. When an athlete is on the start line at the Olympics, the only voice they have inside their head is their own. Confidence in their own mind is everything. If the coach gives too much instruction because they want to ‘save’ the athletes from making mistakes, then they may be helping them in that moment but are bypassing the opportunity for the athlete to make and strengthen that connection themselves. From a mental development perspective, the job of the coach is to support the athletes in correcting themselves. This is a subtle but profound difference.

Our relationship with goals

The difference between being busy and making progress boils down to your ability to internalise clear goals. It is these that give you direction.

There is a universal truth that rings true for all industries – the consistently high achievement of teams and individuals doesn’t happen by accident. No one can achieve success simply by turning up and seeing what happens. You certainly wouldn’t want your surgeon to do that if you were having an operation, and neither would your team want you to do it. Of course, the more skill and experience you have, the more you might be able to avoid planning and preparation, but if success is built upon consistency, then hoping for the best is not going to work.

Despite the unquestionable merits of setting goals as a means of making meaningful progress, I often notice a lot of resistance when it comes to mapping out clear goals. I suspect this is because goals can be scary – once you’ve set a goal, you’ve created the conditions in which success or failure become real. This in turn can induce stress because your goals require you to learn things you don’t yet know, set standards, be disciplined and productive, and challenge the limits of your ability. But this stress shouldn’t be seen as a bad thing. It’s this challenge that creates the intensity you need to be more focused and committed to every step along the way. The heightened sense of challenge and intensity that comes about through setting clear goals cannot, and should not, be avoided.

You often notice when people are shying away from the real challenge of goals because they define them too broadly. In doing so, you ignore the myriad of smaller challenges that sit underneath it. This is great for peace of mind, but rubbish for actually achieving it or getting better. Phrases like ‘we need to improve our diversity in the business’ roll easily off the tongue if you don’t have to do anything about diversity. A simple label can make a complex problem go away, but it can obscure complexity so much that you lose sight of it. And that can come as a great relief.

I spend a significant amount of time turning unclear goals into clear ones – both for myself and in helping others. By doing this, you often discover a multifaceted problem consisting of many parts. All of these parts play differently to your strengths, weaknesses, insecurities and confidence. The only thing to do at this point is to separate them out into their own discrete challenges and goals. This way, goal setting becomes less about articulating a nice clear outcome in one neat sentence (as is the focus of SMART goals, which stands for Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, Timely). Rather, it’s about having a network of interlinking goals that all feed off one another. Importantly, this is exactly how the brain works, using neural connections to create patterns and associations from one thing to another, allowing us to see the world as a whole system rather than as millions of individual entities (which would be chaotic and confusing). This interconnection of goals becomes our ‘mental blueprint’ for success, enabling us to visualise our goals as a dynamic map rather than just a static end-point. I will share an example of this in the next section and using Figure 9.1.

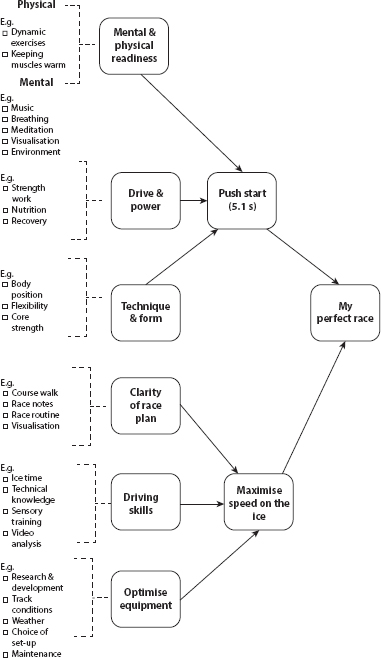

FIGURE 9.1 Example of a goal-setting tree used in skeleton

Understanding the principles that sit behind why you do things allows you to focus on what really matters, while letting go of the noise – the things that just aren’t important. This is arguably one of the greatest skills of high-performing teams. My experience with British skeleton was a great example of this. I remember the first couple of weeks I spent with the team, which was really about observation and seeking to understand the demands of the sport. Having observed the team and got to know their individual habits and routines, I played back to them what I had noticed and asked them why they did certain things in a particular way. The most common responses I got? ‘Because I’ve always done it like that.’ ‘Because my coach has told me to do it like that.’ ‘Because the world champion does it like that, and if it’s good enough for them, it’s good enough for me.’ At face value, all legitimate reasons, but none of these responses demonstrates an understanding of how it actually makes them better at the sport, how it contributes towards their system for getting the best out of themselves.

Another good example of this is the US women’s football team, who for years have been pretty much unbeatable in the sport. Unshackled by convention (which in Europe has been forged by the men’s game over many decades), the American women started with a blank piece of paper and asked the simple question: ‘How do we get good at this?’ Consequently, they have taken a very different approach to recruiting and developing their players, and have adopted the latest advances in sport science far more readily than their European counterparts. During the 2019 Women’s World Cup I heard one of the commentators remark, ‘It’s amazing how well the Americans do, considering they don’t play any of their football in Europe.’ I couldn’t help but ponder the irony of this statement. Surely, it’s because they don’t play in Europe – they haven’t been restricted by unhelpful conventions and therefore are able to think and play differently.

Goal setting in this way helps you to make the most of your limited energy by helping you to challenge the very nature of what you do and why you do it. This is the reason why goal setting is nearly always one of the first conversations I have with a client. Here are some example questions I find useful to have up my sleeve:

- What exactly would you like to achieve or aim for?

- Why is achieving this so important to you as a person?

- How effective are you being in how you get there?

- What makes the biggest difference towards achieving this goal?

- What do you find yourself doing in a certain way because you’ve always done it that way?

- What are you not doing that you know you should be?

- What have you learned from experience that might help you?

- How and when do you apply this experience in order to keep moving forward?

These have the potential to be quite challenging questions, but they further highlight the importance of being able to clarify the goal along with its discrete challenges.

Designing your mental blueprint

Becoming the architect of your own mind requires you to design a mental blueprint. The mental blueprint is effectively a mind map for success. It breaks down big goals and aspirations into discrete areas of performance and then further into everyday habits, routines, skills and techniques. This is a much more dynamic way of goal setting than simply defining your outcome in one neat sentence. It maps out how one goal relates to another, which adds meaning and purpose to the fabric of everything you do.

These mental blueprints became essential to the athletes and coaches on the British skeleton team. It was effectively a plan on a page for achieving success – whatever ‘success’ meant to each individual. It also helped them to live and breathe an Inside-Out mindset by reminding them of how much they could control. Figure 9.1 shows a slightly watered-down example of this.

The idea of calling it a ‘blueprint’ was not just about internal branding. It was very deliberate. A blueprint isn’t just a vision for what you want to build – it’s a detailed intent. By having a blueprint for the perfect race, you create a consistent vision to strive towards. Many times I have been challenged on using the word ‘perfect’. It sits uncomfortably with some people and I understand why. So let me explain what I mean.

The blueprint ultimately links to visualisation and how you see yourself performing. For any given scenario we all have an expectation – for example, ‘I have to stand up on stage and deliver a presentation to 100 people’. At this point the goal is rather vague and focused more on the output than the input. So what happens when you start to add more details? How do you want to address them? What do you want to wear? What do you want to say exactly? How will you stay calm and relaxed? How long will you give yourself? How will you use the space? So now you have the makings of a blueprint, all that’s left is to imagine what good will look like in each of these areas. But do you want to visualise good – maybe with the occasional stumble and slightly less impact – or do you want to visualise perfect?

You see, I think we actually put more undue pressure on ourselves by not being able to imagine what perfect looks and feels like – even if we never achieve it in reality.

When it comes to mental imagery, anything other than perfect creates room for ambiguity and doubt. In exactly the same way, the blueprints for a building represent the exact dimensions and characteristics for that building, but when the building gets built, is it perfect? Not in the true sense – there will be small inconsistencies that naturally come about through either human error or working with raw materials. But does this mean there is no point in having the blueprint in the first place? No, absolutely not. If the blueprint didn’t exist, then the whole project would be full of inconsistencies and vulnerable to gross errors.

In the skeleton team I heard the same nervousness about creating a blueprint. The key to using it was understanding the difference between expectance and acceptance. It’s more compelling to work towards a well-defined blueprint with the acceptance that things do not always go perfectly than to work towards a poorly defined goal with an expectation of achieving it.

You might argue that this philosophy is far easier to live by when the activity you are trying to be world class at is relatively contained and without too many elements outside of your control. In the army we had the motto, ‘No plan survives contact with the enemy.’ Boxer Mike Tyson put it just as eloquently: ‘Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.’ But that’s not the same as saying, ‘Don’t bother with a plan.’ I can’t speak for Tyson, but certainly in the military, planning is key to adapting.

Throughout his career World Cup-winning rugby player Jonny Wilkinson had a clearly defined vision of the perfect game of rugby, not because he ever expected to play it but because it was an essential reference point for how well he responded to familiar scenarios and how he executed his skills. In doing so, it helped him to respond positively to mistakes as well as the inevitable twists and turns of the game.

Quieten your inner critic

There is another important role of the mental blueprint. Each of the skeleton athletes typically started their blueprint of the perfect race by breaking down the race into the push start at the top of the track and then maximising their speed on ice. Then they would break down their perfect push start into smaller areas of focus until they got to the granular detail – take a deep, relaxing breath, place the sled into the grooves of the track, drive off with the back leg, and so on.

Once you get down to this level of detail, you don’t leave any room for ambiguity. You simply need to focus on the routine, one step at a time. By understanding how you have arrived at this point, you can let go of the workings-out and focus on the quality of your routine. This gives you the confidence you need – thinking clearly and positively.

This helps to answer a concern I hear a lot when it comes to mental training. Is there a danger that we overthink what we are doing? The overthinkers reading this will understand immediately the perils of this. Trying to process so much information, the brain is unable to focus on anything. It can be disorienting and paralysing for many people. If this is you, then you would be forgiven for not wanting to try any exercises that encourage you to think any more. But this is the point. You need to do the thinking upfront so that you don’t have to do it at the point of performance, when all you should be focusing on is doing.

If you haven’t done your homework, it leaves you vulnerable to your inner voice and critic. ‘Are you sure about this?’ ‘Is this the right thing to be doing?’ ‘What are other people doing?’ ‘If you get this wrong, you’re going to look stupid.’

Never is this principle more important than when you are under pressure to get results. As we discovered earlier, when you are under pressure your mind is much more susceptible to anxiety and negative thinking.

In the absence of a plan to maintain focus it’s more likely that clear thinking will give way to fear or panic. The simple act of planning can prime the brain to stay focused. Planning while in a calm and rational state of mind helps you to prioritise your attention and do all the difficult calculations upfront so that you don’t have to when you’re under pressure.

Staying focused on your own race

If your blueprint is an intellectual process, then the reality of executing the blueprint is very much a lived experience. If the blueprint represents the instructions for being at your best, you still need to follow the instructions. This is easier said than done, as anyone who has tried building flatpack furniture will testify. If you think you know best and decide to freestyle it, you run the risk of getting it wrong and having to start again (as I am all too aware).

In the world of athletics, there is no greater reason to ignore the instructions than the sight of other people racing ahead of you. And there is no better example of the mental blueprint at work than Kelly Holmes’ performance to win the women’s 800 metres Olympic gold at the 2004 Athens Games. After the first lap Kelly found herself in last place. Many people assumed this was her intent because that’s all they could see. Watching the race unfurl, it would be easy to think that she deliberately placed herself at the back in order to then move forward through the order. In reality, she was trying to be neither at the back nor at the front – she was simply focusing on running her own perfect race.

One of the BBC commentators that night, Brendan Foster, suggested that the victory was down to consistent pacing. Kelly’s times for each lap were exactly the same – 58.2 seconds precisely – suggesting to me that she had a plan in her head that wasn’t governed by what the others were doing. Her plan was governed by the internal blueprint of what the perfect race should feel like. She was racing her perfect race. The fact that other competitors ran off quickly at the beginning was neither here nor there. Kelly stuck to her blueprint, which takes a huge amount of discipline, trust and focus.

This is exactly the same sentiment that many traders and hedge fund managers in the money markets talk about. Successful financial trader Martin Burton once explained that the most important thing for any trader is to focus on their own system regardless of what the market is doing. Traders who abandon their own method to chase the market can expect only one thing: consistent losses coupled with the odd success. Those who stay focused on their plan will enjoy consistent success coupled with the odd loss.

In reality, following your own plan is as much an emotional process as it is an intellectual one. Therefore in Chapter 11 we explore the role of emotions in being at our best.