5

Predators and Protection

PREDATORS ARE A POTENTIAL PROBLEM for all shepherds. Although coyotes kill more sheep than dogs do, predation by dogs actually impacts more shepherds. Bears and wildcats can also create nightmares for a shepherd, and occasionally birds of prey (eagles and hawks) and carrion birds (vultures and ravens) are the culprits.

According to the American Sheep Industry Association, predators in the United States killed about 368,000 sheep and lambs during 1994, representing a loss to their owners of close to $18 million. It is estimated that coyotes were responsible for about two-thirds of those losses.

Managing for Predators

Not all “predators” actually kill sheep, and predators are important members of the food chain, creating a balance that nature depends on. Predators keep populations of wild herbivores, such as deer and elk, from overpopulating their ecosystems, and they feed on lots of small rodents and rabbits. They’ll also eat insects and carrion, which is often abundant along highways. When they do kill, they aren’t trying to ruin your day, cut into your profit, or break your heart; they’re simply following their survival instincts.

Predator species tend to be opportunistic animals, seeking the easiest target to meet their needs. In other words, they usually go for young, old, weak, or sick animals first, though some have been known to attack mature, healthy animals that are in their prime. All predators become more aggressive as their hunger increases — during a drought, for instance — and may attempt to take anything they can get their paws on.

As a shepherd, you can learn to manage your flock so that a predator will decide that eating at your house is a lot harder than chasing mice and rabbits. The box below will give you some ideas on how to minimize predation. Also keep in mind that your flock will suffer from less predation if it is strong and healthy, so good feed and excellent health care pay in more ways than one.

Identifying Predation and Predators

Sometimes predators get a bum rap: if the corpse of a dead sheep has obvious bite marks, it’s natural to think that a predator was the perpetrator. But remember, sheep die from a number of causes, and unless you actually see a predator attacking a live animal, the sheep may have died of natural causes and then been fed on by scavengers.

Coyotes

Wile E. Coyote may have looked the fool in all of his encounters with the Road Runner, but he’s not a good example of the species. Coyotes are intelligent, curious, and adaptable. In fact, they’re expanding their range into urban and suburban areas of the United States and finding satisfactory homes there.

Coyotes usually attack at the throat, but sometimes they’ll grab at a haunch, bite the top of the neck, or attack in the soft flesh under the belly. They generally select lambs over adults, unless hunger has made them desperate. They tend to eat the organs first and then the flank or behind the ribs.

Smaller lambs and those born to young, old, or crippled ewes are more commonly victims than those of middle-aged and healthy ewes. Researchers have found that coyotes are more likely to take the smallest lamb from a set of twins or triplets than to take a larger, single lamb. If a coyote is preying on a flock, one approach to dealing with it is to place a livestock protection collar on all susceptible, small lambs. The collar contains a poison that the coyote ingests when it attacks the lamb’s throat. The advantage of this collar is that it targets only the killer and does not injure other coyotes or critters that aren’t killing the sheep. However, these devices are illegal in some states and must be used by a trained and certified applicator.

Dogs

Dogs are a special class of predator for shepherds, and according to the American Pet Products Manufacturers Association, there are plenty of these predators out there. The U.S. “owned,” or pet, dog population is estimated at more than 75 million, which means that there are more than six dogs for every sheep (and that number doesn’t include the countless feral and abandoned dogs).

These predators can be more dangerous than coyotes, as one or two dogs can maim and destroy dozens of sheep in one night. One dog attack on a flock can make the difference between a profitable year and an unprofitable one, and many people have been driven out of the sheep business because of dogs.

Fido and Spot don’t have to be wild, vicious, or even brave to chase sheep. When dogs chase sheep, they’re following their natural impulse to chase whatever runs. Unfortunately, sheep run at the slightest disturbance. The offending dogs are not as much at fault as owners who don’t keep their pets at home.

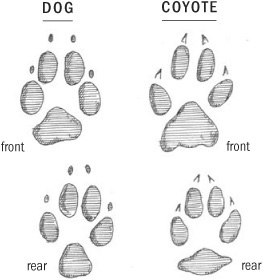

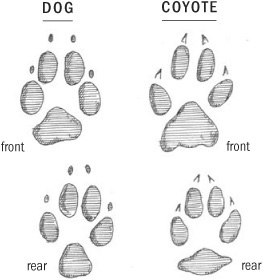

If you have problems with predators, it helps to be able to identify their tracks. The coyote track is about 3 inches (7.5 cm) long for the front foot and 2½ inches (6.3 cm) for the rear. The size of dog tracks varies depending on the size of the dog, so attempting to differentiate a dog from a coyote based on track size alone doesn’t work. Notice that the pads vary. If you live where wolves present predator problems, look for a doglike track that is about 5 inches (12.7cm) long in the front.

Dogs attack rather indiscriminately — they grab at any part of a sheep they can. Sheep often survive dog attacks but may be badly injured. Even dogs that are too small to physically kill or maim a sheep can still cause heart failure in older ewes and abortion in pregnant ewes. Broken legs also often result when dogs chase sheep. Dogs that actually kill and eat sheep display feeding habits similar to coyotes, going first for the organs and then the flank.

Other Predators

Wolves and foxes are less problematic than coyotes for most shepherds, though both are similar to coyotes in their style of predation and feeding. The big bad wolf is able to — and will — easily take down adult sheep. Wolves tend to hunt in packs of two to four animals.

Because of their small size, foxes take only fairly small lambs. (We’ve had lots of foxes around and never lost any sheep or lambs to them, but they annihilated our domestic ducks.)

Bears and wildcats (mountain lions, lynx, or bobcats) are common in more-remote areas, especially in the West. These animals can kill perfectly healthy, strong adult sheep as easily as they can a young or an old sheep. They often kill more than one animal in a single attack and then feed on their favorite parts of each kill.

Bears usually use their massive paws to strike down a sheep. First they eat the udder of a lactating ewe, and then they eat the organs. They may stop at this point and move on to the next sheep, or they may feed on the neck and shoulders as well. Occasionally, they’ll consume the entire sheep in one feeding.

Cats generally attack by biting the top of the head or neck. They have a habit of burying a partially eaten carcass under grass and brush to feed on again later. They first feed on the organs and then the flank.

Eagles and other birds of prey occasionally kill lambs. They attack by dropping out of the air at high speed and closing their talons into the head. Eagles will strip a carcass and leave little except the skin and the backbone.

Laws

Many wild predators are protected or controlled by federal or state laws and regulations. If you have, or suspect you have, a problem with wild predators, call the Wildlife Services office of the USDA or your state’s wildlife office to learn about specific remedies and laws in your area.

Your county Extension agent should be able to tell you the county’s dog laws or, better yet, give you a copy of the county or state laws. You may find that they are strict and well spelled out but lack enforcement.

Guardian Animals

Sheep have been bred for thousands of years to be docile, a trait that makes them easy victims. However, there are other species that become quite aggressive when predators invade their territory, and shepherds have harnessed this trait to defend their sheep for almost as long as they have been keeping sheep.

During the early and mid-1900s, shepherds switched from using guardian animals to using guns, poison, and traps. They adopted the philosophy that any predator was a bad predator and that elimination of all predators was their goal. Recently, the use of guardian animals as protectors of sheep has garnered renewed interest. This results partially from desperation, as poisons and traps are now outlawed in many states and many species of predators are protected by such laws as the Endangered Species Act. But shepherds are also becoming more interested in strategies that protect their sheep without indiscriminately killing all predators.

Attacks usually occur at night or very early in the morning, when you’re normally asleep. A guardian animal is on duty 24 hours a day and is most alert and protective during the hours of greatest danger.

Few guardian animals actually kill predators, but their presence and behavior can reduce or prevent attacks. They may chase a trespassing dog or coyote but should not chase it far. Chasing for a prolonged distance (or time) is considered faulty behavior because the guardian should stay near the flock, between the sheep and danger. The best guardians balance aggressiveness with attentiveness to the sheep.

Whichever type of guardian you’re considering, remember the following:

The guardian needs to bond with the sheep, and the bonding process can take time.

The guardian needs to bond with the sheep, and the bonding process can take time.

Guardians should be introduced slowly, across a fence; it’s usually easier to make the introduction in a small area rather than in a large pasture.

Guardians should be introduced slowly, across a fence; it’s usually easier to make the introduction in a small area rather than in a large pasture.

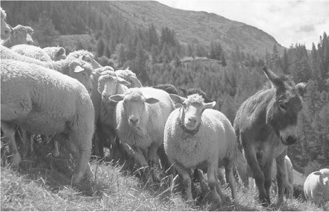

One guardian is generally sufficient on a farm; on open range at least two are required. In large pastures or on open range, bigger animals (such as donkeys and llamas) may be more effective than dogs — though dogs can significantly cut down on losses, even in large areas.

One guardian is generally sufficient on a farm; on open range at least two are required. In large pastures or on open range, bigger animals (such as donkeys and llamas) may be more effective than dogs — though dogs can significantly cut down on losses, even in large areas.

Each animal is an individual and will react differently in different situations. Some individuals don’t make good guardians!

Each animal is an individual and will react differently in different situations. Some individuals don’t make good guardians!

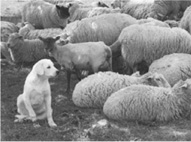

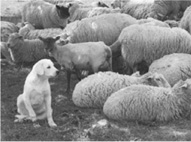

Guardian Dogs

Guardian dogs are most effective on small farms or ranches with good perimeter fences (preferably electric or electric added to woven wire). It could be suggested that a dog is doubly effective if it is protecting its own well-defined territory as well as its flock. Users of guardian dogs say that they cannot place a dollar value on the peace of mind they have from knowing that a dog is with their sheep. It can mean greater utilization of pasture, too, since the sheep don’t have to be herded into a night corral.

A dog needs to save very few lambs to justify its yearly upkeep. The cost per year for a dog decreases the longer it lives, as the purchase price is amortized over a longer period. Let all the neighbors know of the dog’s presence when you acquire it so it will not be shot as an intruder.

To select a dog, you need to find a reputable breeder who regularly supplies dogs for guarding sheep or goats. A dog breeder who also raises sheep is probably a good choice.

Starting with a Puppy

Purchasing a puppy costs less up front than does purchasing a proven guardian dog, but because not all pups work out as good guardians, for a new shepherd it’s probably worth the extra expense to purchase a proven dog from a seasoned shepherd who raises and trains guardian dogs with the flock. These shepherds generally guarantee the dog’s abilities as a guardian.

If you do decide to go the puppy route, the ideal age to remove a pup from the litter is about 8 weeks, although some claim that dogs placed with sheep before they are 2 months old do better than those reared with sheep when they are older than 2 months.

While there is no real way to test the puppy before you raise it, you can observe it in relation to its littermates. Also observe its parents. They should not be overly shy or aggressive and should be free from hip dysplasia, a hereditary joint problem common to large breeds. Most breeders guarantee that a pup will remain free from dysplasia until at least 18 months of age. Pups should have had their shots by 8 weeks of age, confirmed by a veterinarian’s certificate.

Pups that are raised around sheep from a young age bond with them the best.

Guardian Dog Training

A guardian dog can be trained primarily through being raised with sheep. The process involves supervision to prevent bad habits from developing and to establish limits of acceptable behavior.

The Bonding Process

The dog–sheep bonding process requires training of both the sheep and the dog. Sheep will initially accept a puppy more easily if they become acquainted in fairly close quarters; however, they may take a long time to accept the dog if it is turned into a large pasture with them. The normal procedure is to put the pup, when it is 6 to 9 months of age, in a safe enclosure in the sheep area with some sheep as young as 4 months old.

Remember that a guardian dog isn’t a pet — it must bond with sheep, not humans. You don’t have to be mean or abusive to a guardian dog, but his place is outside with the flock at all times, not in the house. Discouraging bonding with humans will keep the dog with the sheep and reinforce its protective instinct. Once the sheep and the guard dog have formed a strong relationship, the sheep will seek out the dog, running to it if there is any disturbance.

Some experienced guardian dog trainers say that you should not handle, pet, or pamper a guardian dog in any way. Others say that not only is it okay to handle and pet the dog, but it’s also important. You want a guardian that can be caught, put on a leash, and walked on the leash when necessary. If you never interact with the dog in a positive fashion, you won’t be able to catch it for vaccinations or medical procedures, to hold it back while the sheep are being sheared, or to handle it in other cases when you need to. The dog should bond to the sheep but be friendly and comfortable with you. You can create this situation by offering praise and a pat when the dog is good.

Other Training Considerations

It is best not to try to train two pups at once, because they will be too inclined to play and may molest the flock in the process. One pup alone will also bond more readily to the sheep. If you wish to use two dogs, pairing a young dog with an older, more experienced dog works better. In this scenario the pup is trained by the older dog.

Because of the potentially high mortality rate and the lengthy training needed, those who rely on guardian dogs as their primary means of predator control should consider having a ready replacement available.

Most folks who use guardian dogs recommend that working dogs be neutered to avoid the problems encountered when the guard dogs or neighboring dogs are in estrus. Neutering is normally done at about 4 months of age.

No amount of proper training or early exposure to sheep can guarantee that a dog will become a good guardian. The instinctive ability, strong in the traditional guardian breeds, plays a great part in success. The main attributes needed are these:

Attentiveness — bonding to sheep and staying with them

Attentiveness — bonding to sheep and staying with them

Appropriate aggressiveness — growling, barking, and fighting if necessary

Appropriate aggressiveness — growling, barking, and fighting if necessary

Defensiveness — staying between the sheep and danger

Defensiveness — staying between the sheep and danger

Trustworthiness — not harming the sheep

Trustworthiness — not harming the sheep

Reliability — wary of unfamiliar humans but slow to attack

Reliability — wary of unfamiliar humans but slow to attack

Guardian Dog Breeds

The various breeds of guardian dogs share similar behaviors. These dogs are ordinarily placid and spend much of the daylight hours dozing. Despite their calm temperament, all of the breeds are fierce when provoked and are wary of intruders, both animal and human. Good-natured breeds are best for small farms, whereas more aggressive breeds are needed for large ranches and open range.

In USDA trials, success rates of guardian dogs did not differ significantly among breeds or between sexes. The Livestock Guardian Dogs Association has a great deal of information on these dogs, as well as information on rescue organizations that take in and find new homes for guardians that couldn’t cut it in the city or suburbia.

Here’s a quick rundown on the main breeds available in North America.

Akbash

Some folks consider the Akbash to be a white-headed variety of the Anatolian shepherd, but others think of it as a distinct breed. Either way, it has proved itself to be a very effective guardian. In fact, in a 1995 survey of Colorado shepherds who use guardian dogs, the Akbash was rated as the most effective guardian against all predators, including bears and lions.

Akbash

Anatolian Shepherd

Originating in Turkey, where it is known as Coban Kopegi (shepherd dog), Anatolian shepherds look just like the Akbash but with a black head and are among the more aggressive of the guardian breeds, even to human strangers. However, they can be trained by socialization to be friendly toward visitors if this is desirable. Strangers must be introduced to the dog, with the owner making sure the dog accepts them. These dogs are extremely possessive of family, property, and livestock.

Briard

Probably the least common breed serving as guardians in North America is the Briard, though its use in this capacity dates back to early in the history of the United States, when Thomas Jefferson imported some for the job. These dogs look like Benji, the movie dog, only bigger, though they are slightly smaller than other guardian breeds. Briards originated in France, and the French traditionally used these dogs for both protection and herding services. They might not be as effective in areas where large predators — bears or cougars, for instance — are a problem, but they should work well where domestic dogs are the primary perpetrators. They may also be of some help where coyotes are a problem.

Briard

Great Pyrenees

The Great Pyrenees is a native of the Pyrenees Mountains, between Spain and France, and is said to have a common ancestry with the Saint Bernard. These dogs are mostly pure white, have a rough coat, and are a most impressive size, weighing from 100 to 125 pounds (45.4 to 56.7 kg).

Great Pyrenees

These are the gentlest of the guard dogs, probably because they have been bred in the United States as pets for many generations. It is also the breed most commonly used as guardians in North America. In USDA trials in Dubois, Idaho, the Great Pyrenees was the only breed that did not at any time bite a human. Although separated from their traditional guardian ancestry, they have generally proved reliable when raised and bonded to sheep at an early age.

Komondor

Another common working guardian breed is the Komondor (plural is komondors or komondorok). It is considered to be of Hungarian breeding but may have been brought there by Turkish Kun families, who migrated with their sheep and dogs in the thirteenth century. Its name means “corded coat” — it has a tremendous coat of hair that hangs in locks similar to that of an Angora goat. The coat may require some maintenance.

Komondor

These dogs have a very serious disposition and are devoted guards, wary of strangers, and independent thinkers. In Hungary, they were also used to protect property and factories. Tests done by the USDA have found these dogs to be more successful with pastured sheep than on open range. This breed has been bred for a thousand years to be independent, but for the dog to be effective, that independence must be carefully channeled by a firm and loving master.

Kuvasz

A Kuvasz (plural: Kuvaszok) has a rough, white coat and dark lips, eyes, skin, and nails. The males weigh 100 to 130 pounds (45.4 to 59 kg), the females 90 to 110 pounds (40.8 to 49.9 kg). Natives of Hungary, many Kuvaszok were killed there during World War II, sadly depleting the original stock.

The Kuvasz is independent and not easily obedience trained — “no” must be strictly enforced. It is very protective of its own property. Once they learn the boundaries, these dogs protect them fiercely. The females seem more alert, whereas the males are more apt to kill predators. They are able and agile runners and catch or corner a predator easily. While capable of functioning without supervision (after proper training), this breed seems to have an emotional need for a certain amount of human company.

Kuvasz

Maremma (Maremmano Abruzzese)

The Maremmas have a sleepy-eyed, relaxed look and a rough coat that is usually white. These guardians have been used in the mountains of Italy to guard sheep for centuries. Usually two or three per flock are adequate to protect all sides from wolves; these dogs protect very well as a team. In Italy their ears are usually docked as pups to prevent a wolf from getting a grip on the head.

Maremma

These dogs are independent but obey single commands they have been taught as puppies. They interpret commands in terms of context and duty — loyalty to the flock always prevails. Maremmas are one of the most successful breeds used in the Livestock Guard Dog Program and are known to be among the calmest of the guardian breeds during the daytime but with instinctive nocturnal alertness.

Shar Planinetz (Sarplaninac)

The first Shar known to be imported into the United States in 1975 was carried down the mountains of Macedonia in a basket on the back of a donkey. This breed is reported to have been a court guardian of kings. Its name comes from the Shar Planina mountain range of Macedonia, in southeastern Europe, in the former Yugoslavia. While this breed is similar to the Maremma and Pyrenees, it is a bit smaller. Its coloring is usually tan to dark brown and is often black. This dog has a quiet, gentle temperament, and many have been trained and distributed by the Livestock Dog Project at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts.

Shar Planinetz

Tibetan Mastiff

Although it is one of the oldest breeds in existence today, the Tibetan mastiff is rare in North America. Its lack of genetic problems is evidence of centuries of natural selection and survival of the fittest. It is black with tan markings, has a distinct double coat with a ruff around the neck and shoulders, and carries its full tail well over its back. In their native land, these dogs travel with caravans of Tibetan sheepherders and traders, defending the herds and the tents of their masters from such predators. They are loyal to master and flock, with antipathy to strangers. The bitches go into estrus approximately every 10 to 12 months (the mark of a primitive breed) and lack dog odor.

Tibetan Mastiff

Keep guardian animals, like dogs, donkeys, and llamas

Keep guardian animals, like dogs, donkeys, and llamas Use lighted night corrals with high, predator-tight fences

Use lighted night corrals with high, predator-tight fences Put bells on some of your sheep; you can hear the bells if the sheep are being chased. High-frequency bells have also been tried with some success, especially for warding off dog attacks, as the sound is unpleasant to the animal. The high-frequency bells haven’t worked as well for coyotes or bears, though in research centers no sheep that was wearing a bell has ever been killed.

Put bells on some of your sheep; you can hear the bells if the sheep are being chased. High-frequency bells have also been tried with some success, especially for warding off dog attacks, as the sound is unpleasant to the animal. The high-frequency bells haven’t worked as well for coyotes or bears, though in research centers no sheep that was wearing a bell has ever been killed. Have sheep in an open field in sight of your house.

Have sheep in an open field in sight of your house. Use coyote snares along fence lines. These will catch both dogs and coyotes. Check the legality of snares in your area before buying any.

Use coyote snares along fence lines. These will catch both dogs and coyotes. Check the legality of snares in your area before buying any. Have a gun. Even a pellet gun can drive off an attacking dog. Although a dog running through a flock of sheep is not an easy target, most predators spook at the sound of a gun shot into the air.

Have a gun. Even a pellet gun can drive off an attacking dog. Although a dog running through a flock of sheep is not an easy target, most predators spook at the sound of a gun shot into the air. Use “live traps” (cages) for trapping dogs, which allows harmless animals to be set free. These traps are of little value with coyotes, which are too wily to be caught. State wildlife officers may supply live traps for bears or wildcats that are repeat offenders.

Use “live traps” (cages) for trapping dogs, which allows harmless animals to be set free. These traps are of little value with coyotes, which are too wily to be caught. State wildlife officers may supply live traps for bears or wildcats that are repeat offenders. Use propane exploders (which produce loud explosions), radios, and other noisemaking devices to provide temporary relief, though predators generally lose their fear of these unless their placement, volume, and timing are changed often

Use propane exploders (which produce loud explosions), radios, and other noisemaking devices to provide temporary relief, though predators generally lose their fear of these unless their placement, volume, and timing are changed often Use a combination strobe light and siren. This device has been developed and tested by the USDA and seems to significantly reduce predation.

Use a combination strobe light and siren. This device has been developed and tested by the USDA and seems to significantly reduce predation. Remove the carcasses of animals that have died from an area where living animals are kept to reduce scavenging, which can evolve into predation

Remove the carcasses of animals that have died from an area where living animals are kept to reduce scavenging, which can evolve into predation Schedule lambing later in the season if you lamb outdoors on pasture. In early spring, most predators are hungry after a long winter and are also feeding their own demanding offspring, yet other feed may still be scarce. By late spring and early summer, other prey (deer and elk, rabbits and rodents, and so on) are more abundant, so the predators aren’t as frantic in their efforts to feed.

Schedule lambing later in the season if you lamb outdoors on pasture. In early spring, most predators are hungry after a long winter and are also feeding their own demanding offspring, yet other feed may still be scarce. By late spring and early summer, other prey (deer and elk, rabbits and rodents, and so on) are more abundant, so the predators aren’t as frantic in their efforts to feed.