Higher levels of fertility and multiple births

Higher levels of fertility and multiple birthsTHE OLD SAYING GOES, “You are what you eat,” and that’s true for your sheep, too. Good nutrition results in these advantages:

Higher levels of fertility and multiple births

Higher levels of fertility and multiple births

Greater milk production and nursing ability

Greater milk production and nursing ability

More wool production and better wool quality

More wool production and better wool quality

Fewer troubled pregnancies and fewer health problems in general

Fewer troubled pregnancies and fewer health problems in general

Quicker lamb growth

Quicker lamb growth

Flocks that are malnourished, however, suffer from every imaginable problem, including higher predation, disease, abortion, and premature lambing. Undersized lambs — those that haven’t reached full size before birth — have less chance of survival and lose more body heat after birth than do big, healthy lambs.

Raising sheep is an efficient way to convert grass into food and clothing for humans, but pasture alone is seldom adequate to feed sheep 12 months of the year. Thus, some supplements (grain, hay, minerals) are necessary. Feeding time is also a good time to check on your sheep, feel the udders of ewes close to lambing, and note eating habits, which greatly reflect their state of health. Count the sheep, particularly if you have any wooded pasture where one could get snarled up or be down on its back and need help.

Although a few “foods,” like sugar water, can be absorbed directly from the stomach into the bloodstream, most foods are unusable until they are broken into molecules, which are made up of groups of atoms. This process is called digestion, and it has mechanical, chemical, and biological components.

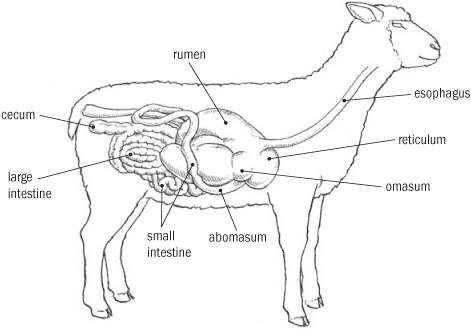

Like cows, goats, and deer, sheep are members of the class of animals known as ruminants, who have a unique, four-stomach digestive system.

The top of the mouth in the front of ruminants is a hard palate — they don’t have any front teeth on top, though they have top teeth in the back of their mouths. The bottom teeth tear and grind feed against the top palate, providing the mechanical component of the digestive process. Initially, the food is only lightly chewed and combined with saliva to form a small ball, or bolus, of feed. The sheep swallows this bolus, and it enters the rumen, or first stomach.

The rumen is like a biological factory, where microorganisms work to break down feed through a fermentation process. We’re inclined to think of all bugs (that is, bacteria and other microorganisms) as bad, but those that normally reside in the rumen are not only beneficial; they are absolutely essential to the animal’s survival. These bugs are called flora and have evolved through a mutually beneficial, or symbiotic, relationship with the sheep over many aeons.

Digestion in sheep is a complex process that takes place in a four-part stomach system. The four parts are the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum.

The rumen of a mature sheep has a capacity of between 5 and 10 gallons (18.9 and 37.8 L), and each gallon (3.8 L) has about 200 trillion bacteria, 4 billion protozoa, and millions of yeasts and fungi. Keeping this work crew active and healthy so they can do their jobs well is an important function of shepherds, even if they don’t usually think in these terms. A key to rumen health is making dietary changes slowly, so that the flora have a chance to acclimatize to new feed regimens.

Some heavy items, like whole grain and stones, may bypass the rumen and go directly into the second stomach, or reticulum. Grain that bypasses the rumen won’t be as thoroughly digested, which is why it’s a good idea to feed cracked grain or whole grains mixed with hay. That way, most of the feed will get some time in the rumen.

The fermentation that occurs in the rumen produces a significant amount of gas, which an animal must pass by belching. Occasionally, an excessive accumulation of gas or foamy material builds up in the rumen, causing bloat.

From the rumen, a slurry of well-fermented feed passes on to the reticulum, then to the third and fourth parts, or the omasum and the abomasum. The abomasum is sometimes called the true stomach, because it functions in a way that’s most similar to that of single-stomached creatures, including humans. Digestion in these latter parts is primarily a chemical process during which enzymes break down the feed as it passes through.

The four-part stomach system allows ruminants to eat — and digest — feeds that other critters can’t take advantage of. Specifically, it enables them to digest cellulose, which accounts for 50 percent of the organic carbon on earth (but we can’t digest it). Being able to digest cellulose enables sheep to receive maximum benefit from all the amino acids present in their feed.

The cecum and intestines are the final places through which the feed passes. These organs provide one last chance for some breakdown to occur through both chemical and biological processes.

The small intestine is like Grand Central Station — it’s the place where most transfers occur. Available nutrients, which are now in their elemental and molecular forms, change trains, switching from the digestive “track” to the bloodstream, or the body’s equivalent of a commuter train. This commuter system (veins, arteries, and capillaries) disperses the nutrients to points throughout the body, where they disembark as needed, “feeding” the organs, muscles, and tissues. The other function of the intestinal system is really important: it controls disposal of the waste products that the body can’t use.

One unique characteristic of ruminant digestion is that the animals have to “chew cud.” Cud is a bolus of partially digested material that’s regurgitated into the mouth from the rumen. Unlike the first chewing, which is quick, cud is chewed very thoroughly and then reswallowed. This process serves two purposes: it allows additional mechanical grinding and it provides a continuous source of large amounts of saliva for the rumen, which helps maintain a healthy environment for the flora. Cud chewing happens off and on during the day; all together, it takes up about 6 hours on a daily basis.

At birth, lambs lack a fully developed rumen. In fact, at first the rumen is relatively small (25 percent of total stomach capacity) and the abomasum is relatively large (60 percent). By the time the lamb is 4 months old, the rumen is almost fully developed (75 percent of stomach capacity) and the abomasum is about 10 percent of stomach capacity. This means that lambs can’t digest cellulose early on.

Lambs shouldn’t be weaned until their rumen is fairly well developed; the earliest point at which this occurs is around 45 days. Lambs that are weaned too early are likely to have stunted growth, and some die.

Right after birth, a lamb is capable of absorbing antibodies from the mother’s milk directly into its bloodstream through the large intestine. Typically, antibodies (more about these natural disease fighters in chapter 7) would be broken down in the rumen, but the lamb’s rumen isn’t working yet. Also, antibodies are normally too large to be absorbed through the intestines. To adjust for this, nature provides a brief window of opportunity when the antibodies can pass through the intestinal wall and into the bloodstream as a way to jump-start the baby’s immune system. Nature also made special accommodations by pumping up the first milk, or colostrum, with extra-large doses of the antibodies that float around in the ewe’s system.

Lambs must receive colostrum as soon as possible after birth, because the intestinal lining begins shutting down from the moment of birth until it can no longer allow the passage of antibodies. Picture a sieve that is at first large enough to pass marbles but is continually closing down until not even one grain of sand can pass through. This closing process takes anywhere from 16 to 48 hours.

Although lambs can survive without the nutrition provided by the colostrum, it is very difficult for them to survive without the disease-protecting antibodies that it contains. When your ewes have been vaccinated prior to lambing season, they’ll pass along immunity from the vaccine through the colostrum. If it’s not possible for a lamb to receive colostrum from its mother (for such reasons as death, disease, and rejection), it will need colostrum from another ewe. To be ready for such emergencies, collect and freeze some colostrum before you need it. Cow or goat colostrum may be substituted for ewe colostrum in a pinch and is often available for the asking from local farmers, especially if there are dairy farms in the area, but the best colostrum is from a ewe vaccinated prior to lambing for the diseases that are endemic to your area.

There are also commercial preparations that are useful when colostrum is not available. These milk-whey-antibody products transfer a certain amount of immunity to the newborn when mixed with a milk replacer (or diluted canned milk or cow’s milk) for the first day. These products are available through a veterinarian or mail-order catalogs (see the Resources section).

The advantages of ewe (or even cow) colostrum from your own farm is that its antibodies are “farm specific” and can protect the lamb against any organisms that the ewe (or cow) was exposed to on your farm.

Emergency Newborn-Lamb Milk Formula

While there is no satisfactory substitute for colostrum, in the worst-case scenario a lamb can be fed the following mixture for the first 2 days, rather than just starting out with milk replacer. This recipe packs a little extra punch that benefits weak babies.

YIELD: APPROXIMATELY ONE DAY’S SUPPLY

26 ounces milk (prepare by mixing half evaporated, condensed milk with half water)

1 tablespoon castor oil (or cod-liver oil)

1 tablespoon glucose or sugar

1 beaten egg yolk

1. Mix well, then give about 2 ounces at a time the first day, allowing 2 to 3 hours between feedings. Use a lamb bottle; in a pinch a baby bottle will work (enlarge the nipple hole a little by making a small X opening with a knife). When the lamb is a few days older, lamb nipples, which are larger, should be used.

2. On the second day, increase the feedings of the formula to 3 ounces at a time (or 4 ounces for a large, hungry lamb), 2 to 3 hours apart.

3. On the third day, the formula can be made without the egg yolk and sugar and the oil can be reduced to 1 teaspoon per 26 ounces of milk.

4. After the third day, you can gradually change to lamb milk replacer. Do not use milk replacer that is formulated for calves; it is too low in fat and protein. Your local feed store or veterinarian can special order lamb milk replacer if it’s not in stock. Goat’s milk is also a good lamb food, so if you have it on hand, you won’t need powdered milk replacer.

One surefire way to tell if the lamb is actually getting milk while it’s nursing is to watch its tail: if lambs are getting milk, those little tails swing back and forth like a flag in a good breeze. If the tail is not in motion, you may have a problem. Constant crying may be another indication that something is amiss, but not always — some lambs will starve to death without making a sound. For the first week or so, make sure that the ewe has milk (by hand milking some out of each nipple) and that the lamb is actually getting some. A lamb that’s getting milk will have a puffed-out belly, but one that’s not getting any has a sunken belly and its skin piles up in folds. Some ewes may come into milk only to dry up after a day or two, so never assume that a ewe will continue to milk after the first day. Be vigilant while the lambs are little.

The ewe’s milk should be sufficient if she is well fed. However, if a young ewe does not have sufficient milk, supplement it with a couple of 2-ounce bottle feedings for the first 2 days, preferably with milk taken from another ewe or with newborn milk formula. Insufficient milk letdown can sometimes be resolved by injections of oxytocin, available from your veterinarian. If the quantity is still not sufficient for the lamb, supplement it with a couple of 4-ounce feedings of lamb milk replacer during the first week, then increase to feedings of about 8 ounces when the lamb is 2 weeks old. Poorly fed old ewes also may have a scant milk supply. If you are feeding an orphan or a lamb whose mother has no milk, see the box above.

Bottle-fed lambs require extra care. Never overfeed. It’s better to underfeed than to have a sick lamb, which happens easily with bottle-fed babies. Overfeeding can cause a type of scours, or diarrhea, that can be deadly. Bottle-fed lambs are also more prone to bacterial and viral infections.

During bottle feeding, cleanliness is critical to lamb survival. Keep bottles, nipples, and milk containers clean. Keep milk refrigerated, warming it at feeding time. Use care if warming in a microwave oven, because it can easily become too hot, and a lamb with a scalded mouth won’t do well.

Nutrients perform three basic functions for an animal: they support structural development, which includes strengthening bones, muscles, tendons, wool, and skin; they provide energy; and they regulate body functions. Although each type of nutrient (proteins, vitamins and minerals, water, carbohydrates, and fats) helps with more than one of these basic functions, each has a role at which it excels.

Unlike carbohydrates, which may contain as few as 20 atoms, proteins are made up of thousands of atoms. Creating something out of so many parts can be made simpler by constructing prefabricated substructures. The structures that are used to make up protein molecules are called amino acids, and there are about 20 essential ones. Proteins are constructed by altering the combinations of these acids. Ruminants can easily obtain all the necessary amino acids from plants, but most sheep have a higher requirement for protein than do other species of livestock, because protein is a major constituent in the development of wool.

Protein is higher in legumes than in grasses and can be supplemented by feeding legume hay or cubes, field peas and soybeans, sunflower seeds (which are also really high in energy), and brewer’s yeast or grain. Some commercial protein supplements contain animal proteins, such as bone- and blood meal. Although these often provide a less-expensive source of protein than plant supplements, they may contribute to disease transmission. (Scientists suspect that feeding these types of animal proteins contributed to the spread of mad cow disease in Europe.)

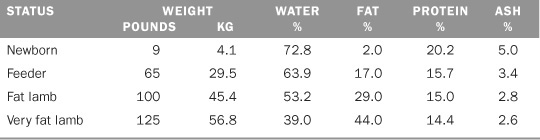

BODY COMPOSITION OF LAMBS AT VARIOUS AGES

Vitamins and minerals could be considered the “regulators” of a sheep’s diet. These regulators can be likened to switches in a house; they turn things on and off when needed, adjust the temperature to keep things comfortable, and help process information. Vitamins, minerals, some forms of protein, and enzymes are all critical to regulation. Vitamins are usually adequately supplied in good green feeds, like pasture and hay. Minerals can be supplemented with a trace mineral mix or block — just make sure the one you choose is specifically for sheep, because those prepared for cattle and horses may contain too much copper.

Vitamins and minerals are required in only very small quantities, but shortages — or excesses — of a critical vitamin or mineral can have grave impacts on your flock’s health. Deficiencies of vitamins cause diseases like rickets and anemia; overdoses are toxic. Deficiencies and excesses are usually the result of soil mineral imbalances, which vary from farm to farm and from region to region.

The first and most important nutrient (though people don’t always think of it as such) is water! Animals can live for up to 10 days without food but may not survive for 2 days without water. Water, in adequate quality and quantity, must always be available. Water serves the following functions:

Keeps sheep cool in hot weather (but even in the dead of winter, it’s necessary)

Keeps sheep cool in hot weather (but even in the dead of winter, it’s necessary)

Aids in transporting nutrients throughout the body

Aids in transporting nutrients throughout the body

Carries waste out of the body

Carries waste out of the body

Is required for the chemical reactions that take place throughout the body

Is required for the chemical reactions that take place throughout the body

Keeps cells hydrated and healthy

Keeps cells hydrated and healthy

Water should be kept clean. The ideal temperature for water is about 50°F (64°C). (In northern climates, sheep may meet quite a bit of their water needs by eating snow, but they should still be given an opportunity to drink water at least once a day.)

Moisture in feeds also affects the sheep’s drinking habits; very moist feeds reduce water intake and dry feeds raise it. Hot summer pasture has very little moisture in it.

To cope with heat, sheep lose moisture through their skin, which adds to the need for ample water. Providing shade helps keep down moisture loss, but the sheep still need clean, fresh water. Also, access to shade should be limited and regulated, like controlling movements through the pasture, because shaded areas that are overused contribute to parasite problems.

Ewes with nursing lambs need extra water to make milk. On average, mature sheep drink between 1 and 2.5 gallons (3.8 and 9.5 L) of water per day. Late-gestation and lactating ewes are toward the top of the scale.

Carbohydrates make up about three-fourths of the dry matter in plants, so they’re one of the most significant nutrients in a sheep’s diet. Sugars, starches, and fiber are all classes of carbohydrates, and their proportions in an individual plant vary, depending on the plant’s age, the environmental factors, and the type of plant. For example, sugars make up a higher proportion in young plants and fiber is in a higher proportion in older plants.

Carbohydrates are named after their atoms of carbon (atomic symbol C), which are attached to molecules of water (H2O). A simple sugar molecule might be made up of six carbon atoms attached to six water molecules (C6H12O6), and it’s a readily usable nutrient, providing an instant burst of energy. Starches are composed of groups of sugars, strung together like holiday lights. Since both sugars and starches are easily digested, they provide high feed value.

Fiber is made up mostly of lignins and cellulose. Lignins are virtually indigestible, but the cellulose is readily digested by the bacterial fermentation that takes place in the rumen. Sheep, like other ruminants, can make use of this feed supply that’s abundant in grass, hay, and other forages.

Like the carbohydrates, fats (and fatty substances) are made up of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, but the proportions are very different. For example, olein, a kind of fat that’s commonly found in plants, has a chemical formula of C57H104O6, meaning that there are 57 carbon atoms, 104 hydrogen atoms, and only 6 oxygen atoms.

Fat is an essential nutrient — especially for young, growing animals (including people). It provides almost twice as much energy as carbohydrates do, and it helps an animal control its body temperature.

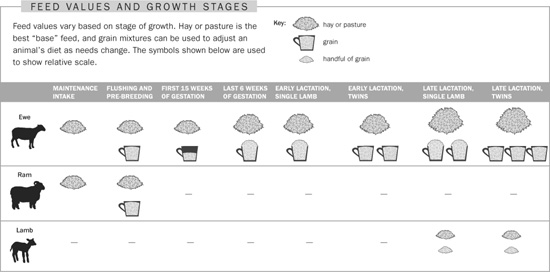

What and when you feed is dependent on the animal’s stage of life and its point in production. The same quality and quantity of feed supplement is not needed at all times. Lambs and young animals need more and higher-quality feed (relative to their size) than mature animals; lactating ewes need more than dry ewes; and during the breeding season, rams need more than they do during the off-season.

Sheep prefer to eat during daylight hours. They begin about dawn, and when given free choice, as on a pasture, they eat on and off throughout the day until dusk. They eat at night only if they have no choice, and then won’t eat as much.

Because sheep must have time during the day to rest and chew cud, the feed must have sufficient nutrients to meet all the sheep’s needs during the day. If pregnant ewes are fed poor-quality hay in winter, when there are fewer hours of daylight, their nutritional needs will not be met and they will require supplementation with grain.

Sheep are gregarious and eat more and better when they are in a group than when they are alone. Thus, if you’re just starting out, buy two or three lambs instead of one. They like to eat as a group but won’t mix with other flocks very well once a bond has developed in the existing flock. Place two flocks together, and they’ll each stake out a “home territory,” separate from each other, even if they’re in the same pasture.

Sheep avoid grazing near their own feces but don’t seem to mind grazing around the feces of other species. They like higher ground better than lower ground and do well grazing with other species, such as cattle, goats, horses, and even pastured poultry. In fact, there is tremendous benefit from grazing several species together:

Since they don’t share the same internal parasites, multispecies grazing reduces parasites in all species by breaking up parasite cycles.

Since they don’t share the same internal parasites, multispecies grazing reduces parasites in all species by breaking up parasite cycles.

There are fewer predation problems when sheep are grazed with cows, horses, or llamas.

There are fewer predation problems when sheep are grazed with cows, horses, or llamas.

Since different species eat slightly different amounts and varieties of the available feed, the land can carry more animals by weight of multiple species than it can of a single species; in university research, it’s been found that meat production per species is increased by up to 125 percent (for example, lambs and calves grow quicker) when several species are grazed together.

Since different species eat slightly different amounts and varieties of the available feed, the land can carry more animals by weight of multiple species than it can of a single species; in university research, it’s been found that meat production per species is increased by up to 125 percent (for example, lambs and calves grow quicker) when several species are grazed together.

A sheep’s stomach can adjust to a great variety of feed, provided that changes are made gradually. A sudden change of ration, such as sudden access to excess food, can cause death. Rumen flora can adapt to the diet, but they cannot adapt quickly.

Any kind of abrupt change of diet will disturb the rumen, and that type of disturbance not only causes acute problems, like bloat, but can also cause chronic problems. Sudden changes interfere with the synthesis of A and B vitamins. Vitamin A in particular acts as an anti-infection vitamin. Insufficient vitamin B results in lack of appetite, emaciation, and weakness.

A good rule of thumb is to make any changes to a feed program no quicker than 10 percent per day. If you’re purchasing new sheep, try to find out what kind of feed they were eating before you get them home so you can slowly switch them to your own program.

Nutrient needs vary according to an animal’s stage of production. During maintenance phases, animals require the least number of calories relative to their body weight. During reproduction or growth, requirements are higher.

Ewes: Maintenance, prebreeding (see Flushing on page 272), early gestation, late gestation, early lactation (adjusted according to single, twin, triplet, or litter births), and late lactation (also adjusted to number of lambs).

Lambs: Birth through weaning, weanling to finishing, finishing for feeder or replacement.

Rams: Maintenance, prebreeding, breeding.

Assuming you have good-quality pasture or high-quality hay, the following general guidelines are appropriate. If your pasture or hay is of lesser quality, you may need to feed a little more grain than the amounts specified below. If the reproductive cycle is timed to the peak of high-quality grass production in the spring, you’ll need little if any supplemental grain for lactation. If you plan to lamb in the winter, though, you’ll definitely want to follow the pre-breeding guidelines.

1. Seventeen days before turning the ram in with the ewes, give up to ½ pound (0.23 kg) of grain per ewe, starting gradually for the first few days. This is called flushing, and it increases ovulation.

2. The ram should start receiving up to ½ pound of grain also, but you can wait until about a week before he’s turned in to begin supplementation. After breeding season, begin reducing his feed until he’s back to just hay or pasture.

3. Continue giving the ewes the ½ pound for about 4 weeks after mating, then taper off gradually. This may prevent resorption of the fertilized ova.

4. Feeding light grain, say,  pound (0.05 kg) per ewe per day, is okay until the last 5 weeks of pregnancy.

pound (0.05 kg) per ewe per day, is okay until the last 5 weeks of pregnancy.

5. During those last 5 weeks of pregnancy, the ewe should be on an increasing plane of nutrition to prevent pregnancy disease (an upset in the metabolism cycle of carbohydrates that may occur in ewes carrying multiple fetuses), gradually working up to ½ pound (0.23 kg) or more per ewe.

6. For the 6 to 8 weeks of lactation, ewes with single lambs should have approximately 1 pound (0.5 kg) of grain per day, while a ewe with twins should have 1½ to 2 pounds (0.7 to 1 kg), plus hay for each. Again, taper off as the lambs eat more grain and hay (in their creep feeder).

7. Start diminishing the quantity 10 days before weaning until the ewes receive no supplemental grain, leaving feed in the creep feeder for the lambs.

See pages 182–83 for feed charts that can help you balance a ration to optimize performance. More information about grain is given under Types of Feed, starting on page 182.

Measure the quantity of grain given each day by using the same container, or number of containers, for each feeding. Sheep do not thrive as well when the size of their portions fluctuates. When given regular feedings at an expected time, sheep are less likely to bolt their feed and choke. Too much variation in feeding time is hard on their stomachs and the rest of their systems.

Although feeding at an expected time is important for all sheep, for pregnant ewes it also makes a difference what time you feed. In some university trials, regular feeding of ewes at around 10 A.M. helped reduce the incidence of night-to-early-dawn lambing. Other recent tests suggest that late-afternoon feeding is better; shift to even later times as lambing approaches. Both feeding schedules concentrated lambing into primarily daylight hours.

Although pasture should be a primary feed source, grains, hay, and a variety of vegetables can also be put to good use. Remember, though, no sudden changes in diet — an abrupt change can paralyze a sheep’s digestive system and cause death from acidosis, an impacted rumen, enterotoxemia, or bloat.

Whole grains are better for sheep than crushed grain. For instance, rolled oats have so much dust that they can cause excessive sneezing, leading to prolapse in heavily pregnant ewes and breathing problems in lambs. Unprocessed corn and wheat still contain the valuable germ, or embryo, that’s located within the grain kernel and is typically removed during milling. This germ is rich in vitamin E — a vitamin that helps ewes protect their lambs from white muscle disease (more about this in chapter 8).

Whole grains, fed with hay, promote a healthy rumen, where the feed gives better conversion to growth. On the other hand, a diet consisting mainly of pelleted or finely ground feed causes the rumen to become inflamed.

The inflammation traps debris and dust, causing a vicious cycle of further inflammation.

A well-managed pasture is the very best source of feed for your sheep. It is economical and provides them with the food nature intended them to eat: fresh grass, legumes, and a few forbs thrown in (generally, in a pasture these are weeds and woody species). It also allows them the chance to behave like sheep: to run, and jump, and lie comfortably chewing their cud as the grass bends around them in the breeze.

Managing pastures is part art, part science. The goal is to keep plants in the pasture growing fast, and this is accomplished by clipping or grazing them before they reach maturity (that is, set seed) but not clipping or grazing them so close to the ground that they will lose a great deal of energy and fail to thrive. To achieve this, practice managed grazing (sometimes called rotational grazing, management-intensive grazing, or pulsed grazing).

In managed grazing, the pasture is subdivided (usually with electric fence) into smaller paddocks, and the animals are moved among these pastures. A good way to start out with managed grazing is to subdivide the pasture into at least eight paddocks. When you put your flock into a paddock, you want to make a visual estimate of how tall the average plants are and graze them to about half that height. Then move the flock to the next pasture.

There are a number of good books on the subject listed in the Resources section (including my Small-Scale Livestock Farming: A Grass-based Approach for Health, Sustainability, and Profit). On the Internet, my favorite place is ATTRA — the National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service Web site (www.attra.org; look at grass farming under the livestock area). And to really become a pro, subscribe to The Stockman Grass Farmer, a magazine dedicated to raising animals on grass and marketing them (see Resources also).

For most shepherds, hay is an extremely important foodstuff. It carries our animals through winter and drought conditions. Unfortunately, though, hay quality varies more than the quality of almost any other feed crop grown in North America — and the variation can be dramatic across the same species of plants grown for hay and within the same locale.

Why is hay quality so variable? Two things affect it: the timing of the cut and weather, weather, weather! Let’s look at timing first. For hay to be at its peak quality, it needs to be harvested just as the plants hit early maturity — in other words, at the beginning of the flowering stage but before seeds have been set. At this stage the plant has a rich green color, good plump leaves, and fine stems and is producing the highest TDN. A second timing factor is the time of day at which the crop is cut: the best hay is produced when the farmer can cut in early afternoon. The dew is off, and the sugar in the plant is at its highest. Most farmers know this. And most farmers want to put up hay at just the right time. But work schedules and equipment breakdowns or availability sometimes interfere, and the weather often fails to cooperate. If Mother Nature sends rain when the crop is ready, the farmer may have to wait to start harvest, thereby letting the plants become overly mature. And if the rain comes once the crop is cut and drying in the field or before the bales are retrieved from the field, then the quality of even the best-timed cutting quickly suffers.

After hay is cut, it is typically left in the field in windrows and allowed to dry. The drying process can seriously impact quality. If the hay is baled before the stems have dried well, the hay will mold. If it is allowed to dry too much before baling, the leaves will shatter during raking and baling, thus yielding poorer quality. Ideally, for most types of hay, the bales will be put up when the moisture content is around 15 percent, but again, ideals are tough to make happen in the real world. Hay producers will use a rake or a tedder (a machine that stirs and spreads the hay) to fluff the windrow and turn it over to speed the drying process, but even with these tools, it can be a challenge, particularly in highly humid climates, such as the Midwest and Northeast, where getting the hay to such a low moisture level in the field can be almost impossible. In these areas, many hay producers are using organic acids to help with curing.

Once it is baled, hay should be retrieved from the field as quickly as possible (particularly for small square bales — the type most often used by shepherds) and then stored in the darkest part of the barn to preserve the vitamin A content, which is depleted by exposure to sunlight. Careful storage is necessary to avoid weather damage and nutrient loss. Exposure of the bales to rain can not only leach out minerals but can also result in moldy hay, a cause of abortion in ewes. If you have no barn, hay can be stored under tarps.

The lower the hay quality, the more you have to feed. Lots of heavy stems in the hay mean that the sheep will eat less. A certain amount of hay is always discarded: some is pulled out onto the ground and wasted (pile this in the garden twice a year), and some is uneaten stems (take the clean ones out of the feed rack for clean bedding for lamb pens). If you buy two different kinds, or grades, of hay, save the best for the pregnant ewes. Late in a ewe’s pregnancy, the hay she’s fed must be of high quality, as the growth of the lamb will crowd the ewe’s stomach and leave little room for bulky low-nutritive feed. The greener the hay, the higher the vitamin content.

Legumes, such as alfalfa and clover hay, are also high in calcium, magnesium, iron, and potassium. The protein content in legume hays varies from 12 percent to 20 percent, depending on what stage it is cut at (highest protein yield occurs when it’s cut young, or in the bud) and on its subsequent storage. (Alfalfa got its name from an Arabic word meaning “best fodder,” which is most appropriate.) But legumes can also be high in phytoestrogens, or plant-based estrogen-type chemicals; these naturally occurring chemicals can interfere with breeding. Red clover has the highest concentration, followed by other clovers, and then by alfalfa, so it is usually best to not feed any clovers and to reduce the percentage of alfalfa you feed during flushing and breeding season (see Flushing, on page 272) for more information). Bird’s-foot trefoil, another legume, doesn’t contain high concentrations of phytoestrogens, so it is a great substitute if you can find it or grow it. Legumes can also contain an imbalance of calcium to phosphorus, which may result in urinary calculi (see page 258), a particular problem for young males.

Our hay of choice throughout most of the year is a legume/grass mix. If you can find hay with 20 to 30 percent alfalfa, it is a perfect feed for the foundation of your flock’s feeding regimen most of the year. Use an appropriate amount of grain to balance the ration according to season, age, and other production criteria.

The feeding tables on pages 396–97 will help you determine the supplements needed to provide adequate nutrition.

Windfall apples, gathered and set aside out of the rain, can be a welcome addition to the winter diet but in limited quantities. Sheep love apples — they even prefer the overripe and spoiled ones — and a few apples a day adds needed vitamins. An excess of apple seeds, however, especially the green seeds, can be toxic.

Fresh pomace from apple cider making is good feed for sheep in small quantities if you have not sprayed your apples. Fermented pulp is not harmful if fed sparingly, but decomposed pulp is toxic.

Molasses is another treat for sheep and is a good source of minerals. The sugars enter the bloodstream quickly, so it is of value to ewes late in pregnancy to prevent toxemia — but not in excess.

Discarded produce from the grocery store is another treat. Lettuce, cabbage, broccoli, celery, and various fruits past their prime for human consumption are often available at the local store. Fed sparingly, or regularly in measured quantities, they are a good addition to the diet.

Plant carrots, rutabagas, turnips, or beets for a succulent treat in fall and winter. These provide good roughage and variety in the diet. Avoid potatoes, as once sprouted they can be toxic to sheep and cause birth defects.

Salt is another year-round necessity for good health. When sheep have been deprived of salt for any length of time and then get access to it, they may overindulge and suffer salt poisoning. The symptoms of this disorder are trembling and leg weakness, nervous symptoms, and great thirst. It can be treated by allowing access to plenty of fresh water, but better yet, prevent it by keeping salt available at all times. Mineralized salt, especially that containing selenium in areas where the soil contains low levels of that mineral, is recommended. Just make sure it is a mineral salt for sheep, not cattle, as minerals for cattle may contain toxic levels of copper. Regular access to salt is said to be useful, along with roughage, to prevent bloat, which is one of the most serious digestive upsets.

This salt feeder has a capacity of 14 pounds (6.5 kg) and can be made quickly from one 1″ × 8″ × 5′ board and 24 galvanized 8d nails.

CUTTING LAYOUT

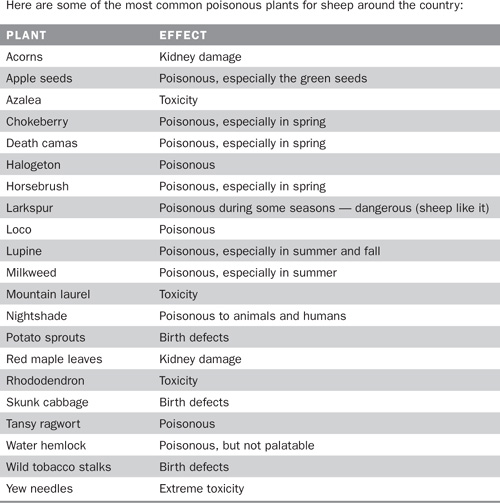

All areas of North America are host to some poisonous plants. The good news is that animals usually don’t chow down on these plants unless they’re very hungry. But sometimes an individual animal will start eating a poisonous plant even if there’s plenty of good feed available.

Check with your county Extension agent to learn which plants in your area are poisonous (make sure you specify that you’re interested in sheep, as some plants that are poisonous to cattle or horses don’t affect sheep at all). Or try a Web search for the name of your state, poisonous plants, and sheep. As poisonous plants vary from state to state, there isn’t one all-encompassing site to recommend, but with a little persistence you will find abundant information on the Internet.

With any new pasture, walk around it and note any unusual or unfamiliar plants. If there are plants you cannot identify, send several fresh whole plants (stem, leaves, flowers, seeds) to the state agricultural college wrapped in several layers of newspaper. Someone there should be able to identify them and advise about their toxicity.

After you know what toxic plants are around, develop a plan for dealing with them. Some plants are toxic only during certain stages, so you can keep animals out of the area during that period. Others are mildly toxic and require the ingestion of huge amounts before they affect animals, so you’ll just need to be aware and keep an eye on things. Some are highly toxic and are best eradicated before pasturing sheep in the area where they’re growing. As you learn about these plants, also learn how to handle them — some can be poisonous to humans just from touching them.

When plant poisoning is suspected, call your veterinarian promptly. Knowing what’s causing the poisoning can increase the chances of effective treatment. Keep the sick animal sheltered from heat and cold, and allow it to eat only its normal, safe feed.

POISONOUS PLANTS

Again, in most instances, animals do not happily eat toxic plants. However, if they are overly hungry and better food is not available, they may eat anything at hand. If they have been deprived of sufficient water for an extended period, this can cause them to reduce their feed intake. Then, when they suddenly get enough water, their appetites increase greatly, and they may devour almost anything. Have water and feed available at regular times in needed quantities.

Overgrazing of pastures, which means shortage of grass, can cause sheep to eat plants that they would otherwise avoid. It is better to keep fewer sheep well fed and healthy than to keep more than your pasture and pocketbook can sustain.

Other kinds of poisoning occasionally happen. For these, prevention is definitely the best cure. Store all chemicals and cleaning supplies where animals can’t get into them, and always, always, always properly dispose of waste containers! Look out for the following substances, which are often found around the farm or ranch:

Waste motor oil, disposed of carelessly

Waste motor oil, disposed of carelessly

Old crankcase oil (high lead content)

Old crankcase oil (high lead content)

Old radiator coolant or antifreeze (sweet and attractive to sheep)

Old radiator coolant or antifreeze (sweet and attractive to sheep)

Orchard spray, dripped onto the grass

Orchard spray, dripped onto the grass

Weed spray (some have a salty taste that animals will go after if they don’t have access to salt)

Weed spray (some have a salty taste that animals will go after if they don’t have access to salt)

Most sheep insecticidal dips and sprays

Most sheep insecticidal dips and sprays

Old pesticide or herbicide containers, filled with rainwater

Old pesticide or herbicide containers, filled with rainwater

Old car batteries (sheep like the salty taste of lead oxide)

Old car batteries (sheep like the salty taste of lead oxide)

Salt — Required for health, but when deprived and then allowed free access, sheep may ingest large quantities, causing salt poisoning

Salt — Required for health, but when deprived and then allowed free access, sheep may ingest large quantities, causing salt poisoning

Commercial fertilizer. Be careful not to spill any fertilizer where sheep can eat it, and store the bags away from the sheep. They may nibble on empty bags. Several rainfalls are needed to dilute the chemicals after a field is fertilized, and it still may not be safe unless the pasture grass is supplemented with grain and hay. Symptoms of fertilizer toxicity are weakness, rapid open-mouthed breathing, and convulsions. For a home remedy, use vinegar, 1 cup (236.6 mL) per sheep, as a drench.

Commercial fertilizer. Be careful not to spill any fertilizer where sheep can eat it, and store the bags away from the sheep. They may nibble on empty bags. Several rainfalls are needed to dilute the chemicals after a field is fertilized, and it still may not be safe unless the pasture grass is supplemented with grain and hay. Symptoms of fertilizer toxicity are weakness, rapid open-mouthed breathing, and convulsions. For a home remedy, use vinegar, 1 cup (236.6 mL) per sheep, as a drench.

Cow supplements containing copper. Some cattle mineral-protein blocks contain levels of copper that are lethal for sheep. Some mixed rations intended for cattle may also have copper and should not be used for sheep.

Cow supplements containing copper. Some cattle mineral-protein blocks contain levels of copper that are lethal for sheep. Some mixed rations intended for cattle may also have copper and should not be used for sheep.