9

Flock Management

GOOD MANAGEMENT FOR REPRODUCTION is a key to profitability and peace of mind. Reproduction really goes right through lambing, but I’ve broken the topic into two chapters: this chapter covers the ram, the ewe, breeding, and pregnancy, and the next chapter covers lambing and early-life management of your flock. The optimal time for lambing varies greatly among geographical areas. The desired lambing time may depend on the availability of pasture, local weather conditions, labor and time restraints, targeted lamb markets, and so on. Choose your lambing time to fit your priorities, and plan to breed about 5 months before you want lambs.

When the cost of hay or grain is a consideration or if you want to minimize labor, lambing should be timed to take advantage of new pasture growth. Some shepherds living in areas with moderate winters and hot summers may choose to lamb in autumn or early winter to maximize weight gains, knowing that lambs experience very poor weight gain in hot temperatures. Those in the northern areas often begin lambing in March or April to avoid the severe subzero temperatures of midwinter. People in temperate coastal climates may let the rams run with the ewes all year and let nature take its course, if they have no target date for market lambs. What constitutes “early” or “late” lambing depends on your climate.

Successful Breeding

Many factors can influence how good your breeding season is:

Day length. All sheep are photosensitive, meaning that reproductive activity is affected by the length of daylight. In the fall and winter, reproductive activity is highest. Ewes all go into heat and are capable of breeding during these seasons, though some individual ewes and particularly some breeds of ewes can breed year-round, or “out of season.” But even within breeds that are known for out-of-season lambing, the ovulation rate is lower during the spring and summer than it is in fall and winter. Thus, by breeding out of season, you may have fewer lambs.

Day length. All sheep are photosensitive, meaning that reproductive activity is affected by the length of daylight. In the fall and winter, reproductive activity is highest. Ewes all go into heat and are capable of breeding during these seasons, though some individual ewes and particularly some breeds of ewes can breed year-round, or “out of season.” But even within breeds that are known for out-of-season lambing, the ovulation rate is lower during the spring and summer than it is in fall and winter. Thus, by breeding out of season, you may have fewer lambs.

Temperature. Although high temperatures don’t have as much effect on reproductive activity as day length, they do have some. During hot weather, rams may be infertile, and ewes are likely to miscarry.

Temperature. Although high temperatures don’t have as much effect on reproductive activity as day length, they do have some. During hot weather, rams may be infertile, and ewes are likely to miscarry.

Age. Ewe lambs generally begin cycling later than mature ewes, don’t tend to have as strong a heat, and don’t release as many eggs per ovulation. Reproductive activity may be reduced in aged ewes.

Age. Ewe lambs generally begin cycling later than mature ewes, don’t tend to have as strong a heat, and don’t release as many eggs per ovulation. Reproductive activity may be reduced in aged ewes.

Nutrition. Flushing, or increasing the level of nutrition prior to breeding, increases reproductive activity.

Nutrition. Flushing, or increasing the level of nutrition prior to breeding, increases reproductive activity.

General health. Good health pays off with more lambs born and greater lamb survival.

General health. Good health pays off with more lambs born and greater lamb survival.

Artificial Insemination

Artificial insemination (AI) is another option for small flocks. AI is a little trickier in sheep than in cattle, and it must be done by a veterinarian or a specially trained AI technician. However, it provides a good ram’s semen to a small flock without your having to keep a ram.

Interest in using AI in sheep production is increasing because this technique allows breeders to increase genetic diversity in their flocks. For example, Susan Mongold, a breeder of Icelandic sheep, fought her way through several years of red tape to be able to import semen from Iceland. Why? To increase the genetic diversity within her flock. “The Canadian flock, from which we got our animals, originated from two imports of only eighty-eight animals. We wanted the very best genetics to improve our flock,” she told me.

Artificial insemination is a procedure that uses a laparoscope (a fiberoptic instrument similar to the one commonly used on humans). Since AI in sheep is a surgical procedure, due to the ewe’s curved cervix, all ewes that are candidates for AI should be in good health and should not be overly stressed beforehand. The procedure needs to be synchronized with the estrous cycle; ewes are often treated with hormones so that they all come into heat at the same time. Artificial insemination is not for everyone. However, it is opening new doors for some shepherds, and as the system evolves, it will benefit more producers.

The Ram

The ram contributes to the genetics of all your lambs, so obtain the best ram you can get. Ordinarily, the “best” ram is a well-grown 2-year-old that was one of either twins or triplets. Being a member of a multiple birth in no way affects the chances of twinning in the ewes he breeds — this is controlled by the number of eggs the ewe drops to be fertilized, which is influenced by genetics and encouraged by flushing. However, the ram’s daughters will inherit a genetic inclination toward having twins, especially if their mothers had the same inclination. In other words, both a ewe’s and the ram’s twinning capabilities will show up in the following generations. The ram also greatly influences other traits, such as conformation and fleece type.

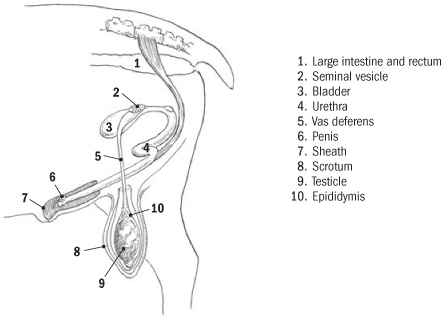

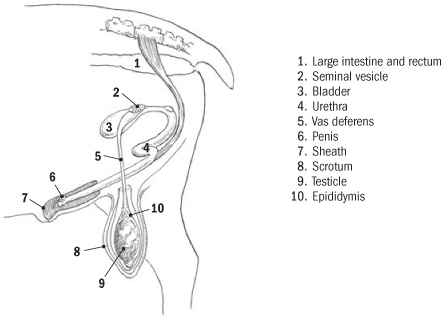

PARTS OF THE MALE REPRODUCTIVE TRACT

Use a young ram sparingly for breeding. One way to conserve his energy is to separate him from the ewes for several hours during the day, at which time he can be fed and watered and allowed to rest.

One good ram can handle 25 to 30 ewes. In a small flock where the ram gets good feed, you can expect about 6 years of use from him, though you don’t want him breeding his daughters, granddaughters, and great-granddaughters indiscriminately. On open range he may last for only a couple of years.

For a really small flock, it may not make sense to purchase a ram. When we first started our flock, we were breeding for late-spring lambs, and Sherry, from whom we bought the girls, was breeding for early-spring lambs. So, for a nominal fee, we’d use one of her rams to breed our ewes. Sherry always had several rams, to make sure she had at least one to breed her stragglers, and we were spared the expense of keeping a ram for the first year or so. Then, during a year when our flock had grown to a pretty large size, we needed a second ram, but rather than purchase it, we worked out a similar arrangement with another nearby shepherd with an even larger flock.

Preparing the Ram

Whether you are buying a new ram or borrowing one, try to obtain him well enough in advance of the breeding season so that he becomes acclimatized to his new home. A week is about the minimum you want him around before he has to “work,” and 2 weeks is better. Keep him separated from the flock and on good feed and pasture until breeding time. Remember to change his ration gradually when you first bring him home, and use good judgment in feeding; excess weight results in a lowering of potency and efficiency, so keep him in good condition.

During the breeding season, feed the ram about 1 pound (0.5 kg) of grain per day, so that if he is too intent on the ewes to graze properly, he will still be well nourished. Remember that he needs good feed throughout the breeding season and for a short time thereafter. After all, he’s “working” hard!

There are two schools of thought about what to do with a ram after the ewes are bred: The first school says remove him from the flock as soon as breeding is complete and keep him separated until next breeding season. The second school says leave him with the flock most of the year. Okay, so which approach should you use? That depends on your breed of sheep and your management goals. Ask yourself the following questions:

Can your breed of sheep breed at a very young age — in other words, could he breed his daughters before you want them bred?

Can your breed of sheep breed at a very young age — in other words, could he breed his daughters before you want them bred?

Do you have a breed that can breed out of season? If so, he may rebreed ewes when you don’t want them bred. On the other hand, maybe you want lambs to be born throughout the year.

Do you have a breed that can breed out of season? If so, he may rebreed ewes when you don’t want them bred. On the other hand, maybe you want lambs to be born throughout the year.

Do you have facilities where he can easily be kept separated for long periods? Do you want to deal with a separated critter?

Do you have facilities where he can easily be kept separated for long periods? Do you want to deal with a separated critter?

We’ve always had good luck leaving the ram with the flock all summer. Our ewes dropped their lambs on the pasture in early summer, and since Karakuls don’t typically breed too early, the ram was no problem running with the group. In early fall, when the hours of daylight started to drop and the chances of his breeding the ewes came on, we’d move him to a separate pen until January, when we were ready to breed the ewes. If Karakuls had been a breed known for breeding throughout the year, we would have separated him immediately (though Karakuls are known for a longer breeding season than some other breeds).

Provide a cool, shady place for him in the heat of summer. An elevated body temperature, whether from heat or from an infection, can cause infertility. Semen quality is affected at 80°F (26.7°C) and seriously damaged at 90°F (32.2°C). Several hours at that temperature may leave him infertile for weeks and ruin any plans you had for early lambing. If your climate is very hot in the summer, shear his scrotum just before the hot weather; run him on pasture in the evening, at night, and in the early morning; keep him penned in a cool place with fresh water during the heat of the afternoon. (High humidity and temperature can also decrease his sex drive.)

August is generally the beginning of breeding season for January lambing, though many breeds won’t begin until September. You can wait until later to turn in the ram with the ewes if you want to start lambing later in the spring. The gestation period is 5 months (148–152 days), so count back from your desired lambing date to determine the best date to introduce the ram.

Ewes are in heat for about 28 hours, with 16 or 17 days between cycles, so 51 to 60 days with the ram should get all the ewes mated, including the yearlings, which sometimes come into heat late.

A sense of smell greatly determines a ram’s awareness of estrus in the ewes. Some breeds of ram have keener olfactory development than others and can detect early estrus that would go unnoticed by other breeds. Those with the “best noses” for it are Kerry Hill, Hampshire, and Suffolk rams, in that order.

Effect of the Ram on the Ewes

The presence of the ram, especially his scent, has a great effect on estrous activity of the ewes. This stimulus is not as pronounced when the ram is constantly with the ewes as it is when he is placed in an adjoining pasture about 2 weeks in advance of when you would like the breeding season to start. A teaser ram may also be used (see Ewes, page 270).

Anyone who has had more than one ram at a time is conscious of the social differences seen within a group of rams — one must always assert dominance. Any time rams are reunited after a period of separation, there is the inevitable fighting and head butting until the pecking order is reestablished.

There is a wide range of sexual performance among rams. It has been documented that the mating success of dominant rams exceeds that of subordinate ones. This in itself can cause problems, since aggression potential and ram fertility are not necessarily related. If the dominant ram is infertile, then flock conception rates can suffer.

Ram-Marking Harness

To keep track of the ewes that have been bred, you can try a “marking harness,” which is used on the ram and is available from many sheep-supply catalogs. The harness holds a marking crayon on the chest of the ram. Ewes are marked with the crayon when they are bred. Inspect the ewes each day, keeping track of the dates so you will know when to expect each one to lamb. Use one color for the first 16 days the ram is with the ewes, then change color for the next 16 days, and so on. If many ewes are being re-marked, it means that they are coming back into heat and thus did not become pregnant the previous time he tried to breed them. If you find that this is happening, you may have a sterile ram.

If the weather was extremely hot just before or after you turned him in, you can blame it on the heat. But to be safe, you should turn in another ram in case your ram’s infertility is not just temporary.

Painted Brisket

Instead of a purchased harness, you can daub marking paint on the ram’s brisket (lower chest). Mix the marking paint into a paste with lubricating oil, or even vegetable shortening, using only paints that will wash out of the fleece.

Raising Your Own Ram

One advantage of raising your own ram is that you get to see what he would be like at market age if he were being sold for meat. The older a ram gets, the less you can tell about how he looked as a lamb or how his offspring will look when they are market age.

The way ram lambs are raised can have some effect on their future sexual performance. Studies have shown that rams raised from weaning in an all-male group will show lower levels of sexual performance in later life. When several rams are run with the flock, the dominant ram will breed far more ewes than less dominant rams. If the dominant ram happens to have low fertility, you may be left with unbred ewes.

The “Battering” Ram

“Battering” rams are not funny and can inflict serious, sometimes permanent, crippling injuries. When you are raising a lamb for a breeding ram, do not pet him or handle him unnecessarily. Never pet him on top of his head — this encourages him to butt. Do not let children play with him, even when he is small. He may hurt them badly, and they can make him playful and dangerous. He will be more prone to butting and becoming a threat if he is familiar with humans than if he is shy or even a little afraid of them.

Leading a ram with one hand under his chin keeps him from getting his head down into butting position. A ram butts from the top of his head, not from the forehead. His head is held so low that as he charges you, he does not see forward well enough to swerve suddenly. A quick step to the right or left avoids the collision.

If you have a ram that already butts at you, try the water cure: a half pail of water in his face when he comes at you. After a few dousings, a water pistol or dose syringe of water in his face usually suffices to reinforce the training. Adding a bit of vinegar to the water makes it even more of a deterrent.

A dangerous ram that is very valuable can be hooded so that he can see only a little downward and backward. He must then be kept apart from other rams, because he is quite helpless in this state.

Strange rams fight when put together. Well-acquainted ones will, too, if they’ve been separated for a while. They back up and charge at each other with their heads down. Two strong rams that are both very determined will continue to butt until their heads are bleeding and one finally staggers to his knees and has a hard time getting up. Rams occasionally kill one another. (Never pen a smaller, younger ram with a larger, dominant one.) Once they have determined which one is boss, they may butt playfully but will fight no big battles unless they are separated for a time.

To prevent fighting and the possibility of serious injury, you can put them together in a small pen for a few days at first. In a confined area, they can’t back up far enough to do any damage.

If no pen is available, you have two options:

Use a ram shield, which is a piece of leather placed over the ram’s face that inhibits frontal vision. For a pretty reasonable price, you’ll effectively stop a butting ram without interfering in any of his other functions.

Use a ram shield, which is a piece of leather placed over the ram’s face that inhibits frontal vision. For a pretty reasonable price, you’ll effectively stop a butting ram without interfering in any of his other functions.

“Hopple,” “yoke,” or “clog” the ram — all of which are old European practices.

“Hopple,” “yoke,” or “clog” the ram — all of which are old European practices.

“Hoppling” a ram (the modern term is hobbling) was an old system of fastening the ends of a broad leather strap to a foreleg and a hind leg, just above the pastern joints, leaving the legs at about the natural distance apart. This discourages rams from butting each other or people, because they are unable to charge from any distance and little damage can be done if they can’t run. They may stand close and push each other around but will do nothing drastic. Hoppling also keeps them from jumping the fence, which rams sometimes do if ewes are in the adjoining pasture.

“Yoking” is fastening two rams together, 2 or 3 feet (0.6 or 0.9 m) apart, by bows or straps around their necks, fastened to a light board, like a 2-inch by 3-inch (5.1 cm by 7.6 cm) piece of lumber. Both yoking and hoppling necessitate keeping an eye on the rams to be sure that they do not become entangled.

In “clogging,” you fasten a piece of wood to one foreleg by a leather strap. This slows down and discourages both fighting and fence jumping. Close watching is not necessary.

Ewes

No single ewe has a major impact on your production, but as a collective body, these animals are crucial to success.

Before the breeding season begins, some preparation will make it more successful. Test your ewes (and the ram) for worms, and deworm them as necessary. Also check everybody for keds and other problems. Trim any wool tags from around the tail, and trim their feet, because they’ll be carrying extra weight during pregnancy, and it is important for their feet to be in good condition. By taking care of small problems now, you reduce the chances for more-serious problems later. For instance, if you eliminate ticks before lambing, none will get on the lambs and you will not have to treat for ticks again.

Seventeen days before you want to start breeding, put your ram in a pasture adjacent to the ewes, with a solid fence between them. Research has shown that the sound and scent of the ram bring the ewes into heat earlier.

Some owners of large flocks use a castrated male, or wether, to stimulate the onset of estrus in the flock. This “teaser” is turned out with the ewes about 3 weeks before breeding. Since it always seems that the male lambs make the best pets, this is one way you can keep a pet and feel no guilt for feeding a nonproductive wether!

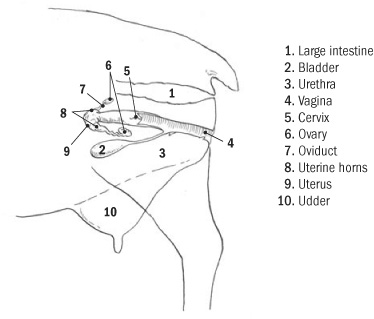

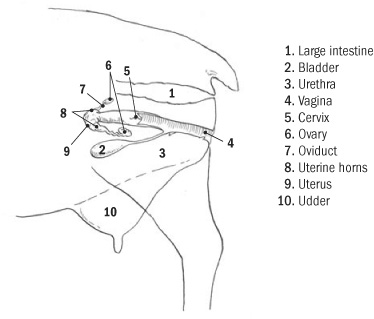

PARTS OF THE FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE TRACT

Never pen the ram next to the ewes before this sensitizing period just prior to breeding. Remember, “absence makes the heart grow fonder.” It is the sudden contact with the rams that excites the females.

Vaccines

The vaccine that is most important to both ewes and their lambs is a multi-purpose vaccine that is effective for Clostridium species of bacteria. Ewes need to be injected twice the first year — the primer shot can be given as early as breeding time or as late as 6 to 8 weeks before lambing, with the booster shot given 2 weeks prior to the calendar lambing date for the flock. For subsequent lambings, ewes require only the booster given 2 weeks before lambing. This protects ewes and their lambs until the lambs are about 10 weeks of age against all of the clostridial diseases, including tetanus.

Among other important vaccines are the following:

A vaccine that protects against chlamydia, which causes enzootic abortion of ewes and vibriosis. This vaccine is typically administered between 1 month and 2 weeks before breeding.

A vaccine that protects against chlamydia, which causes enzootic abortion of ewes and vibriosis. This vaccine is typically administered between 1 month and 2 weeks before breeding.

A vaccine that protects against some forms of pneumonia and other respiratory viruses; this is typically administered 30 days or fewer before lambing.

A vaccine that protects against some forms of pneumonia and other respiratory viruses; this is typically administered 30 days or fewer before lambing.

Flushing

Flushing is the practice of placing the ewes on an increasing plane of nutrition — that is, in a slight weight-gain situation — to prepare for breeding. (It is not as effective if the ewes are fat to begin with, and fat ewes may have breeding problems.) Flushing can be accomplished by supplementing the diet with grain, or better pasture, depending on the time of year you are breeding. It is most productive when initiated 17 days before turning in the ram and continued right up until he is introduced — then begin tapering off gradually, for about 30 days. There seems to be no advantage to starting earlier. This system not only gets the ewes in better physical condition for breeding; it also helps to synchronize them by bringing them into heat at about the same time, which prevents long, strung-out lambing sessions.

Flushing is also a factor in twinning, possibly because with better nourishment the ewes are more likely to drop two ova. The USDA estimates that flushing results in an 18 to 25 percent increase in the number of lambs, and some farmers think it is even more.

You can start with ¼ pound (0.1 kg) of grain a day per ewe and work up to ½ or ¾ pound (0.2 or 0.3 kg) each in the first week. Continue at that quantity for the 17 days of flushing. When you turn in the ram, taper off the extra grain gradually.

The ewes will probably come into heat once during the 17 days of flushing, particularly if you have put the ram in an adjoining pasture. But it’s best not to turn in the ram yet — during their second heat, ewes drop a greater number of eggs and are more likely to twin.

The ewes should not be pastured on heavy stands of red clover, as it contains estrogen and lowers lambing percentages. Other clovers and alfalfa may have a similar effect, though it tends to be weaker in these legumes. Bird’s-foot trefoil, another legume, doesn’t have this effect at all.

Ewe Lambs

The exception to the flushing is the ewe lambs, if you decide to breed them. They will not have reached full size by lambing time, so you would not want them to be bred too early in the breeding season. Don’t breed them until a month or so after you’ve begun breeding the mature ewes. Breeding season is shorter for ewe lambs than for mature ewes. Some breeds mature more slowly, like Rambouillet, and some much faster, like Finnsheep, Polypay, and Romanov.

Ewes that breed as lambs are thought to be the most promising, as they show early maturity, which is a key to prolific lambing. Ewe lambs should have attained a weight of 85 to 100 pounds (38.6 to 45.4 kg) by breeding time, as their later growth will be stunted slightly in comparison with that of unbred lambs. If not well fed, their reproductive life will be shortened, and unless they get a mineral supplement (such as trace mineralized salt), they will have teeth problems at an early age.

If replacement ewes are chosen for their ability to breed as lambs, the flock will improve in the capacity for ewe-lamb breeding, which can be a sales factor to emphasize when selling breeding stock. Choose your potential replacement ewes from among your twin ewes. Turn in these twin ewe lambs with a ram wearing a marking harness or a paint-marked brisket. The ones that are marked, and presumably bred, can be kept for your own flock; sell the rest.

Culling

By keeping the best of your ewe lambs and gradually using them to replace older ewes, you should realize more profit. To know which to cull, you need to keep good records (see Sample Ewe Record Chart on page 394), and this necessitates ear tags. Even if you can recognize each of your sheep by name, you are more inclined to keep more accurate, efficient records with tags than without them.

Record the following information in your books: fleece weight, wool condition, lambing record, rejected lambs, milking ability, lamb growth, prolapse, inverted eyelids, any foot problems or udder abnormalities, and any illnesses and how they were treated. With an accurate recorded history of each animal, you know better what to anticipate.

At culling time, review the records and inspect teeth, udders, and feet. The following types of ewes should be culled:

Ewes with defective udders

Ewes with defective udders

Ewes with a broken mouth (teeth missing)

Ewes with a broken mouth (teeth missing)

Limping sheep that do not respond to regular trimming and footbaths

Limping sheep that do not respond to regular trimming and footbaths

Ewes with insufficient milk and slow-growing lambs

Ewes with insufficient milk and slow-growing lambs

Improvements to a flock require rigid culling. Consider age, productivity (including ease of lambing and survivability), and general health. Udders, feet, and teeth are always prime areas for inspection.

Be objective and practical. The runt you tube-fed and bottle-fed may be adorable, but it is not a viable choice for breeding stock.

Feeds

Do not overfeed ewes during the early months of pregnancy. A program of increased feeding must be maintained during late gestation to avoid pregnancy disease and other problems. Overfeeding early in pregnancy can cause ewes to gain excessive weight that may later cause difficulty in lambing.

Have adequate feeder space (20 to 24 inches [50.8 to 61 cm] per ewe) so that all ewes have access to the feed at one time; otherwise, timid or older ewes will get crowded out. If possible, they should be given a free-choice mineral-salt mix that contains selenium; this can make it unnecessary to inject selenium prior to lambing (to protect lambs from white muscle disease). Never use a mineral mix intended for cattle because it may be fortified with copper at a level that is toxic to sheep. Some geographical areas require selenium supplementation that is above the legal limits available in commercial mineral supplements. Check with your local veterinarian or Extension agent.

Feeding in the Last Four or Five Weeks before Lambing

By the fourth month of pregnancy, ewes need about four times more water than they did before pregnancy. And since 70 percent of the growth of unborn lambs takes place in this last 5-to-6-week period, the feed must have adequate calories and nutritional balance to support that growth.

During the last month of gestation, the fetus becomes so large that it displaces much of the space previously occupied by the rumen. This necessitates giving feed that is higher in protein and energy, as the ewes have trouble ingesting enough feed to support themselves and the growing lambs if they’re fed on low-quality roughage. If they aren’t getting enough protein and energy, they use excessive quantities of stored fat reserves, which can lead to pregnancy toxemia. Poor energy supplementation can also result in hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), which mimics the symptoms of pregnancy toxemia.

A good grain mix would be one-third oats, one-third shelled corn, and one-third wheat (for the selenium content). Barley, if available, is a good feed. Grain rations can be supplemented to 12 to 15 percent protein content with soybean meal or another protein source. Grain and hay should be given on a regular schedule to avoid the risk for pregnancy disease or enterotoxemia by erratic eating. Approximately 1 pound (0.5 kg) of grain per day (more for larger ewes) is a good rule of thumb.

At this time, watch for droopy ewes — ones going off their feed or standing around in a daze. See chapter 8 for troubles ewes may suffer at this time, including pregnancy toxemia. Exercise and sunlight are valuable to all critters but especially to pregnant ewes. If necessary, force exercise by spreading hay for them in various places on clean parts of pasture, once a day, to get them out and walking around.

The Ketone Test

One way to be sure that your prolific ewes — those carrying twins or triplets — are getting enough nutrition (energy) is to check for ketones in the urine — better to avoid pregnancy toxemia (ketosis) than to be forced to treat it later as an emergency.

Ewes that are not getting enough feed to meet their energy (caloric) requirements will use reserve body fat. When fat cells are converted into energy, waste products called ketones are created. Pregnancy disease results when the ketones are produced faster than they can be excreted. They rise to toxic levels in the bloodstream, which can be easily detected in the urine. A simple test kit for ketones, available at a pharmacy, can be used to identify ewes with caloric deficiencies. Use the ketone test results to separate the ewes that need extra feed, thus avoiding underweight or dead lambs and pregnancy toxemia problems.

Day length. All sheep are photosensitive, meaning that reproductive activity is affected by the length of daylight. In the fall and winter, reproductive activity is highest. Ewes all go into heat and are capable of breeding during these seasons, though some individual ewes and particularly some breeds of ewes can breed year-round, or “out of season.” But even within breeds that are known for out-of-season lambing, the ovulation rate is lower during the spring and summer than it is in fall and winter. Thus, by breeding out of season, you may have fewer lambs.

Day length. All sheep are photosensitive, meaning that reproductive activity is affected by the length of daylight. In the fall and winter, reproductive activity is highest. Ewes all go into heat and are capable of breeding during these seasons, though some individual ewes and particularly some breeds of ewes can breed year-round, or “out of season.” But even within breeds that are known for out-of-season lambing, the ovulation rate is lower during the spring and summer than it is in fall and winter. Thus, by breeding out of season, you may have fewer lambs.