Keeping an open mind is a virtue, but not so open that your brains fall out.

—Bertrand Russell, James Oberg

I have a little gremlin on my shoulder. He's about seven inches tall, and usually dresses in dark green or red clothing. He's invisible to you, but I can see and hear him. He sits there, twenty-four hours a day, and tells me what to do. All of my thoughts and conversation originate with him. He whispers into my ear and tells me what I should think, what I should say, and how I should act. In fact, all of my actions are the result of his prodding. Now, you may say that the idea of an invisible gremlin is ridiculous. Nobody would believe in that—where's the evidence? It's just my word that I'm experiencing him. But the fact is, some of the beliefs that we hold have about as much credible evidence to support them as my gremlin. Yet, we continue to believe.

As we've seen, many people believe that houses can be haunted, extraterrestrials have visited the earth, people can be possessed by the devil, and psychics can predict the future. These claims are all very extraordinary, yet the evidence to support them is quite ordinary—and flimsy. And to make matters worse, other competing, more plausible explanations for these experiences exist and are being ignored. Not all evidence is created equal. When forming our beliefs, we need to assess both the quality of the evidence and the reasonableness of the belief. In effect, the more extraordinary the belief, the more compelling the evidence should be to support it.

EXTRAORDINARY CLAIMS REQUIRE EXTRAORDINARY EVIDENCE

The Discovery Channel recently reported on proof for the existence of ghosts—paranormal researchers actually recorded voices of the dead! How did they do it? They taped sounds in a cemetery, and after enhancing the recordings with a number of audio techniques, it sounded like someone was saying “I'd love to find me stone.” The ghost hunters then went to “haunted” Brookdale Lodge in California, asked questions as they walked from room to room, and recorded any sounds in reply. Once again, the responses were inaudible to human ears, but the researchers massaged the very low frequencies of the recordings until you could hear “help me” and “stand over here.” So there you have it. Not only do people report seeing ghosts, physical evidence indicates that their voices can actually be recorded. Seems pretty convincing, doesn't it?

Do you remember the “Paul is dead” phenomenon of the 1960s? It was thought by many that Paul McCartney, one of the Beatles, had died. A simple rumor took hold and quickly gained a life of its own. People began looking for clues of Paul's death in all sorts of places. They analyzed album covers and noticed that Paul was the only one barefoot on the cover of Abbey Road. The most compelling evidence, however, came from an analysis of the Beatles' songs. When some songs were played backward, or were slowed down, people heard phrases like “Paul is dead.” Of course, Paul McCartney is alive and still making great music.

So what can we take away from this? If we have enough data, and massage it hard enough, we can find just about anything we're looking for. From the hundreds of Beatles' songs played backward and slowed down, there's bound to emerge some sound that resembles “Paul is dead.” No one ever said those words in the music, but thousands, if not millions, of people believed it. So it is with the detailed massaging of tapes from haunted houses. By manipulating the recordings, stretching, and condensing the different sounds, we'll be able to occasionally produce a sound that appears to be a ghost speaking to us.

When we evaluate evidence and set our beliefs, we need to keep in mind a simple idea—extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. The concept of a ghost is quite extraordinary. We have to believe that some form of “energy” from our former selves exists, decides to hang around this world for a while, and then decides to communicate or interact with us every now and again. We should have extremely compelling evidence before we accept such an extraordinary belief. Do the tape recordings provide such evidence? We already know from the “Paul is dead” phenomenon that recordings can be easily manipulated to make them sound like all sorts of things. Should we accept such evidence as proof that ghosts exist? Hardly! The quality of that evidence is quite poor.

Of course, paranormal researchers say that such recordings are only one type of evidence. They also point to temperature changes in haunted houses, or the presence of bright lights and ghostly images on photographs. But these phenomena are easily attributed to natural causes. Cold drafts are likely to occur in old houses, and overexposures or reflected light on photographs can look like a ghostly image.1 What about personal sightings? As we'll later explore, there's considerable evidence to indicate that we can misperceive our world, often seeing things that aren't there. This especially occurs when we expect or want to see something. As a result, personal stories do not offer compelling evidence for the existence of ghosts. We need something more tangible.

What about all those other mysterious experiences that yield physical evidence? It turns out that when these experiences are carefully investigated, reasonable explanations typically prevail. For example, my friend Shawn once thought that the spirit of his deceased grandfather was visiting his condo. Why? The door to the downstairs, where his grandfather used to spend a lot of time, was mysteriously locking. This particular type of door could only be locked from the inside, and to do so, you had to push and turn the button on the door handle. How could that happen with no one in the room? The only explanation was a ghostly visitor. Intrigued, I went to examine the door. It turned out that the lock button was sticking, so it just had to be pushed in, but not turned, to set the lock. And, since there was no door stop to prevent the door from hitting the wall when opened, the button was depressed and locked by the wall when the door was thrown open. Time after time, when critically examined, supernatural explanations give way to natural ones.

So does this mean that ghosts don't exist? Not necessarily. It just means that we don't have strong evidence to support that they do exist. But without such evidence, doesn't it make sense to withhold our belief in ghosts at this time? The point is, we have to examine the quality of the evidence for a claim before accepting it. On first glance, there may appear to be considerable evidence to support the existence of ghosts. After all, we have tape recordings, pictures, and personal experiences. But a lot of bad evidence is still bad evidence—sheer volume cannot make the evidence any better.2

Unfortunately, when we form our beliefs, we often give too much importance to the amount of evidence and too little to its quality. Remember the silicon breast implant controversy discussed earlier? People became convinced that implants cause major disease because thousands of women reported serious illness after receiving implants. But a link was not established between the implants and the illnesses. It seemed that there was a lot of evidence, but it was all low-quality, anecdotal data. The volume of evidence in support of a claim should not be the primary factor when setting our beliefs. With evidence, quality is king. As we saw earlier with the case of facilitated communication, a single rigorously controlled study provided much more compelling evidence on the technique's usefulness than did a thousand personal stories.

And yet, we are quick to believe extraordinary claims on the basis of rather thin evidence. We believe in alien encounters and talking with the dead just because some people report they had a personal experience. But if someone makes such an extraordinary claim, they should have some pretty extraordinary evidence, especially if the claim goes against many of the well-supported physical laws of our universe. Some followers of transcendental meditation believe that they can levitate their bodies several inches off the ground during meditation. Should we accept their word for it? If we do, we would have to reject what we already know about gravity. What if we saw it for ourselves? Remember, magicians like David Blaine amaze people by levitating right on the sidewalks of New York. We can be fooled into believing something that isn't actually happening. The entire world of magic depends on it. It's worth remembering that virtually all of the phenomena that paranormal researchers point to as evidence of supernatural or mystical occurrences can be replicated by magicians, most of whom readily admit they're illusionists and they're performing a trick. Doesn't that tell us something?

And so, I have a little gremlin I want you to meet. My gremlin may sound bizarre, but that's because gremlin stories aren't prevalent in this day and age. Since gremlins aren't part of our culture, it's easy to see that we need extraordinary evidence before we believe such a claim. My word isn't good enough. On the other hand, things like alien encounters, Bigfoot sightings, and ghostly experiences are everywhere in our popular media, so belief in them seems more reasonable, even without extraordinary evidence. Don't forget though, at one time people believed in gremlins and fairies.

A look through history reveals an interesting pattern. As Carl Sagan noted, in ancient times, when people thought that gods came down to earth, people saw gods. When fairies were widely accepted, people saw fairies. In an age of spiritualism, people saw spirits. When we began to think that extraterrestrials were plausible, people began seeing aliens.3 You have to ask, are things like aliens the gremlins of today? Why do people who report seeing aliens say they have a humanoid body with a large head and eyes? If an alien from another planet came to Earth, it would likely look very different from a humanoid. Just look at the diversity of life on this planet. Only a few species have two arms and two legs. Imagine the differences that would arise if life formed on an entirely different planet. Yet, we see aliens that look remarkably like ourselves. Why is that? Aliens are typically depicted as humanoid in magazines, on TV, and in the movies. When science fiction accounts in the 1920s and 30s showed small hairless beings with big heads and eyes, people started seeing such creatures. Alien abduction accounts were rare until around 1975, when a TV show depicting an abduction aired. We don't hear much about gremlins and fairies these days. I wonder where they've gone. Abducted by aliens, perhaps?

It Could Be!

Do you remember the movie Animal House? At one point in the film a young freshman, nicknamed Pinto, is smoking pot for the first time with one of his professors. While under the influence, they have a deep philosophical discussion about the true nature of the universe. With the professor's urgings, Pinto says, “OK—So that means that our whole solar system could be, like, one tiny atom in the fingernail of some other giant being?” Looking down at his own finger he then says, “That means that one tiny atom in my fingernail could be one little tiny universe?” When the professor nods in agreement, Pinto asks, “Could I buy some pot from you?”

We often hear people say, “It could be.” Aliens could be visiting us from other planets. We don't know for sure. The problem with this line of reasoning is that it implies that one belief is as good as another. And if that's the case, then there's no such thing as objective truth—reality is just what we believe it to be. However, as Theodore Schick and Louis Vaughn point out, if we believe that all truth is subjective, then no statement is worthy of belief or commitment because every belief is arbitrary. As a result, there can be no such thing as knowledge, because if nothing is true, there can be nothing to know (So why bother going to school?). But while many people believe that anything is possible, that claim can't be true. Some things can't be false and other things can't be true. For example, 2 + 2 = 4, and all bachelors are unmarried, are necessary truths, while 2 + 2 = 5, and all bachelors are married, are necessary falsehoods. In effect, some things are logically impossible. Other things are physically impossible. It's logically possible for a cow to jump over the moon, but it's physically impossible.4

So what's the upshot? Not all beliefs are created equal. Saying, “It could be” doesn't get us anywhere. It's just not a sound argument to use when forming our beliefs. Instead, we have to evaluate the reasonableness of the belief—consider the plausibility of the claim—then evaluate the degree of credible, verifiable evidence in its favor.5

How we think affects what we believe, and what we believe affects what we decide. When our beliefs go beyond the available evidence, they're more likely to be wrong. And, if we base our decisions on those erroneous beliefs, those decisions are more likely to be in error. We therefore need to apply a considerable degree of skepticism when forming beliefs and making decisions.

THE IMPORTANCE OF SKEPTICAL THINKING

If you would be a real seeker after truth, it is necessary that at least once in your life you doubt, as far as possible, all things.

—Descartes

Many people think, as noted earlier, that a skeptic is a cynic—someone who just wants to find the fault in everything. But that's not what a skeptic is. A skeptic is someone who simply wants to evaluate the evidence for a claim before he believes it.6 Skepticism is a method, not a position. A true skeptic doesn't take a strong position until considerable credible evidence is available for believing or disbelieving a claim. In effect, skeptics proportion the extent of their belief by the extent of the evidence for or against a belief. And, of course, a skeptic's mantra is “extraordinary beliefs require extraordinary evidence.”

The hallmark of skepticism is science. People often criticize scientists and skeptics for being too close-minded. They say that skeptics don't believe in things like ESP and ghosts because they just don't fit with their theories of how the world works. But scientists are constantly trying to find support for new, and sometimes bizarre, theories. In fact, a scientist who develops a new theory that is substantiated by the evidence achieves great fame and fortune. We don't remember the scientist who just plugs along testing someone else's ideas, we remember scientists like Darwin and Einstein, who proposed new, earth-shattering concepts. So what's the difference between skeptics and believers in the paranormal and other bizarre claims? Skeptics and scientists require considerable, repeatable evidence before they accept a claim. Don't you think that any scientist would love to find compelling evidence for the existence of extraterrestrials or ESP? He would achieve considerable status and be remembered throughout history.7

And so, one of the goals of skeptics and scientists is to keep an open mind. In fact, true skeptics perform a delicate balancing act, best described by Carl Sagan as follows:

It seems to me what is called for is an exquisite balance between two conflicting needs: the most skeptical scrutiny of all hypotheses that are served up to us and at the same time a great openness to new ideas. If you…have not an ounce of skeptical sense in you, then you cannot distinguish useful ideas from the worthless ones. If all ideas have equal validity then you are lost, because, then…no ideas have any validity at all.8

As we opened this chapter, philosopher Bertrand Russell and NASA scientist James Oberg said, “Keeping an open mind is a virtue, but not so open that your brains fall out.” If this metaphorically describes skeptics, doesn't it make sense to take a skeptical position when forming our beliefs? So why don't we do it more often? Why don't we like to be skeptical? Perhaps it's because we don't like uncertainty and ambiguity, and being a skeptic means we have to accept uncertainty as a major part of life. Skeptics choose not to believe something until there's adequate data supporting that belief. This is a problem for many people, because we typically abhor uncertainty and have a low tolerance for ambiguity. As a result, we want to believe things, even in a world full of ambiguity. However, wanting something to be true doesn't make it true, and wanting to believe is no basis for accepting a belief.

As a skeptic, you have to be comfortable saying, “I don't know.” This makes sense because, in many cases, nobody knows. Some things are inherently unknowable, and other things we just don't know with our current state of knowledge. Given the size of the universe, it's possible that other life-forms exist, but we don't currently know if they do because credible evidence has not emerged to support that belief. A skeptic, therefore, suspends belief in extraterrestrial life for the time being. However, if the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) project, which is scanning the skies for radio signals emanating from other planets, finds compelling evidence of aliens, a skeptic would reassess her position. With skepticism, we have to accept the uncertainty of life—but isn't that better than filling our lives with a number of unsubstantiated, sometimes silly, and potentially dangerous beliefs?

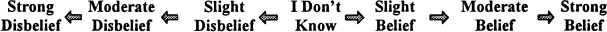

In essence, we should look on our belief as a continuum, ranging from strong disbelief to strong belief, as in figure 2. Importantly, the midpoint of the continuum is “I don't know.”

Given our desire to believe things, we all too quickly end up on the right end of the scale, strongly believing in something despite little credible evidence. However, we need to start at the midpoint, embrace the notion that “I don't know,” and then examine the evidence for or against something. As we evaluate the evidence and plausibility of a claim, we can move farther out on the continuum, either toward strong disbelief or strong belief.9 In that way, we're likely to be more open to different ideas and more likely to set informed beliefs. Of course, the question arises, what's the best approach to take to guide our movement along the belief continuum?

Figure 2. A continuum of belief: As we move from the midpoint, we hold a progressively stronger belief or disbelief.

A FIRST-RATE BELIEF GENERATING TECHNIQUE

Man's most valuable trait is a judicious sense of what not to believe.

—Euripides

As we've noted, it's not only extraordinary beliefs that we have to be skeptical about. We also hold a number of erroneous beliefs that, on the surface, may appear to be plausible. As a result, we have to employ skepticism when forming any belief. So what's a good approach to take when we shape our beliefs? Theodore Schick and Lewis Vaughn proposed the following four-step method that can be quite useful:10

1) State the claim.

2) Examine the evidence for the claim.

3) Consider alternative hypotheses.

4) Evaluate the reasonableness of each hypothesis.

State the claim

When deciding whether to believe something, we need to state the belief as clearly and specifically as possible. We can't be ambiguous—ambiguous claims have too many loopholes that can make them essentially untestable. For example, many people hold the superstition that things come in threes—such as deaths of celebrities—but they don't state a time horizon for the three events. Is it one week, one month, or five years? Without a time horizon, we can be misled into believing the superstition because, sooner or later, similar events will happen in the future.

Examine the evidence

Remember that not all evidence is created equal. As we've seen, anecdotal evidence can lead us astray; human perception and memory can be distorted, and so personal stories can be misleading. Ambiguous data are very difficult to evaluate, and even scientific studies can have errors. And so, we have to proportion our belief not only to the amount of evidence for and against a claim, but to the quality of that evidence.

Consider alternative hypotheses

There are often many possible explanations for phenomena. However, we're not naturally inclined, or taught, to look for competing alternatives, so we often focus on a single explanation (and it's usually the one that we want to believe). Since we also have a tendency to pay attention to information that supports our belief, we start to think it has considerable support. But there's often equally compelling evidence to support other competing explanations, if we simply look for it. We therefore have to make a conscious effort to consider alternative hypotheses and evaluate the evidence for them all. The importance of this step cannot be overemphasized. One of the most critical factors in improving how we form beliefs and make decisions is to be on the lookout for competing explanations.

Evaluate the reasonableness of each hypothesis

After we bring to mind other competing explanations for a phenomenon, we need to evaluate their reasonableness. There are a number of criteria that can be used to evaluate whether one hypothesis is better than another. As a start, here are three important questions to ask:

1) Is it testable?

2) Is it the simplest explanation for the phenomenon?

3) Does it conflict with other well-established knowledge?

Is it testable? When evaluating any hypothesis, the first question to ask is, Can it be tested? Many hypotheses can't be tested. This often happens when we examine extraordinary phenomenon. The inability to test doesn't mean that the hypothesis is false, but it does mean it's worthless from a scientific point of view. Why? If a hypothesis can't be tested, we'll never be able to determine its truth or falsehood. As Karl Popper indicated, a hypothesis has to be “falsifiable”; that is, we must be able to try to prove it wrong.11 If there's no way to falsify a hypothesis, we'll never be able to assess if it's true or false.

As an example, consider my little gremlin. Can we test the hypothesis that I have a gremlin on my shoulder and he's responsible for all my actions? If you say, “Let's see him,” I say, “He's invisible.” If you say, “Let's hear him,” I say, “He only talks to me.” “Ask him to leave so I can see if you still function normally,” you suggest. “Sorry, but I can't—he's there all the time,” I sigh. In effect, for every test proposed, there's a reason why it can't be used to detect my gremlin. As a consequence, the gremlin hypothesis is worthless. As Carl Sagan has noted, “Claims that cannot be tested, assertions immune to disproof are veridically worthless, whatever value they may have in inspiring us or in exciting our sense of wonder.”12

Is it the simplest explanation? Many people learn how to walk over a bed of hot coals with their bare feet. In fact, you can take seminars on how to accomplish that feat from fire-walking gurus—for a few thousand dollars! Firewalkers often maintain that some mental or psychic energy protects them from getting burned, and that they can teach you how to harness that energy. But there's nothing mystical or spiritual about fire walking—it's just the physics of heat capacity and conductivity of the coals. You may have noticed that different materials can be the same temperature, and yet some will burn you while others won't. If you stick your hand into a 350° oven, it feels hot, but it won't burn. If you place your hand on top of a cake in the oven, it still won't burn. But if you touch the metal pan holding the cake, you'll burn instantly. Why? The heat capacity and conductivity of these things are different. The air and cake have low capacity and conductivity, while the metal is high. Even though the coals in firewalking have been heated to 1,200° F, they have low capacity and conductivity, and therefore won't burn your feet—unless you linger too long. So some people are paying thousands to learn how to walk quickly.

What does this mean for setting our beliefs? All other things equal, we should choose the simpler of two different explanations for a phenomenon. By that I mean the explanation that makes the fewest untenable assumptions. The simpler the hypothesis, the less likely it is to be false since there are fewer ways for it to go wrong.13 To accept many of the firewalkers' explanations, you have to assume that some extraordinary psychic or mystical power exists. But you don't need to believe in such mystical power to explain firewalking. The laws of physics offer a simpler explanation.14 This guiding rule of science—choosing the simplest explanation—is called Occam's razor, after the fourteenth-century English philosopher William of Occam. As a general rule, we should always apply Occam's razor to cut away unnecessary and unsupported assumptions when setting our own beliefs.

Does it conflict with other well-established knowledge? I was in Australia awhile back and caught some type of flu. I went to the pharmacy and, as I was searching through the traditional cold and flu remedies, the pharmacist suggested that I try a homeopathic cure. Just to the right of the traditional medicine was a large display containing numerous homeopathic remedies. “Do they work?” I asked. “Definitely, I use them all the time,” he exclaimed.

So what is homeopathy? Homeopathic medicine is based on the belief that very small amounts of substances that cause illness in healthy people can cure a sick person. A fundamental proposition of homeopathy is the law of infinitesimals, which states that the smaller a dose is, the more powerful it is. Doses are diluted to such an extent in homeopathic remedies that, in some cases, not even a single molecule of the active agent is left in the treatment. But that's okay, because as German physician Samuel Hahneman, the creator of homeopathic medicine, believed, a “spirit like” essence was left in the small doses that cured people.15

Homeopathic medicine would certainly not survive Occam's razor. It requires belief in unsubstantiated, unproven “spirit like” essences. In addition, it conflicts with other well-established knowledge that we have about how the world works. There's no other instance in science where a smaller dose of something leads to a greater effect. And yet, homeopathic medicine is based upon that premise. Other things being equal, we should prefer a hypothesis that doesn't disagree with well-established knowledge, since if it does, it's more likely to be wrong. Homeopathic medicine has been tested and shown to be bogus, but millions of people still pay good money for homeopathic treatments.16

CHOOSE THE HYPOTHESIS

It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.

—Aristotle

Let's take a look at a couple of the beliefs mentioned earlier and apply the approach outlined above for forming reasoned beliefs. 17

Therapeutic Touch

Therapeutic touch rests on the idea that we have an energy field emanating from our body and that we can cure disease by detecting and manipulating this energy. A practitioner of therapeutic touch moves her hands a couple of inches above a patient's body to detect and push away any negative energy causing illness. Therapeutic touch is thought by many to be a valid and accepted medical practice. As previously mentioned, it's used in at least eighty hospitals in the United States, and is taught in more than one hundred colleges and universities worldwide. Over forty thousand healthcare professionals have been trained in the technique and about half actively use it. In addition, our government has spent thousands to investigate the usefulness of the technique.18

So, does it make sense to believe in therapeutic touch? Let's begin by stating a specific, testable hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: People have an energy field that emanates from their bodies that can be detected and manipulated to cure disease.

The next step is to examine the evidence for our hypothesis. Practitioners of therapeutic touch point to thousands of individuals who got better after undergoing their treatment. What could be more compelling evidence? People are sick, they get the treatment, they get better. And, this happens in thousands of cases. But these are all anecdotal cases, and we must remember that personal experiences can be misleading. What is needed are controlled experiments. So we continue digging through the evidence in search of some rigorous experimental data.

Figure 3. An illustration of therapeutic touch, where a person waves her hands above a patient's body to drive out negative energy that supposedly causes illness (photograph taken by the author).

A basic foundation of therapeutic touch, that we have an energy field coming from our bodies that can be detected, was tested in a controlled experiment involving twenty-one therapeutic touch practitioners. The design of the study was quite simple, yet elegant. In fact, it was designed by a nine-year-old girl by the name of Emily Rosa for her fourth grade science fair project!19 The practitioners put their hands, palms up, on a flat surface twenty-five to thirty centimeters apart. Emily, who was on the other side of a screen so the practitioners couldn't see her, put her hand eight to ten centimeters above one of the subject's hands and asked them to identify which hand she was above. If the practitioners could detect a human energy field, they should be able to accurately indicate which hand Emily was hovering over. Each subject had ten trials, and the position of Emily's hand was randomly determined each time. Of course, we would expect the practitioners to be right about 50 percent of the time simply by chance alone. Over the course of two different experiments, the average accuracy of the therapeutic touch practitioners was 44 percent—worse than just guessing!

And so, a basic proposition of therapeutic touch, that an energy field can be detected by the practitioners, was found to be highly questionable. But if that's the case, what accounts for all the reports of individuals getting better after undergoing therapeutic touch treatment? To have a more balanced and informed opinion about the issue, we have to consider competing explanations. Two hypotheses come to mind.

Hypothesis 2: People feel better after therapeutic touch because of the placebo effect.

Hypothesis 3: People believe that therapeutic touch cures them because they misinterpret the variability of disease.

The placebo effect is pervasive in medical science—many people feel better after receiving a given treatment, even though the treatment has no real therapeutic component.20 In fact, since medical science has developed most of the treatments with real therapeutic effect in just the last hundred years, it's been said that, “prior to this century, the whole history of medicine was simply the history of the placebo effect.”21 Studies have shown that about 35 percent of patients with a number of different types of ailments receive benefit from placebo pills (e.g., sugar pills).22 Placebos even help about 35 percent of patients with severe postoperative pain. Their effects are so potent that some people actually get addicted to placebo pills.23 And so, many people can get better after a therapeutic touch treatment just because they think it's going to help them. Their “cure” has nothing to do with the technique itself.

In addition, most symptoms exhibit some degree of variability—sometimes they're better, while other times they're worse. We often seek medical help when we feel our worst, so any improvement is attributed to the treatment we receive. However, many illnesses improve on their own naturally, whether a treatment is given or not. It's been estimated that 85 percent of our illnesses are self-limiting—they'll end without any intervention. Even chronic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and cancer can have spontaneous remissions.24 As a result, patients may get better after receiving treatment even though the treatment itself had no real therapeutic benefit.

Now that we have these three hypotheses, let's evaluate them. They are all testable. While therapeutic touch has some evidence in its support, that data is primarily anecdotal, which controlled experiments have brought into question. On the other hand, scientific studies have documented the placebo effect and the variability of illness. When we evaluate the simplicity of the hypotheses, therapeutic touch falls short. Why? Therapeutic touch requires that we believe in some unknown energy field, while placebo effects and the variability of disease do not. In addition, therapeutic touch conflicts with other scientific evidence. Controlled experiments demonstrate that therapeutic touch practitioners cannot discern an unknown energy field that they assume emanate from our bodies. Thus, it seems more reasonable to accept the placebo and variability hypotheses as contributing explanations for why people get better after therapeutic touch.

Similar analyses can be made for homeopathic medicine, magnetic therapy, and many of the other so-called alternative medicines.25 In fact, a number of alternative practices have been tested and shown to be false. Yet, a subcommittee of the US Congress estimated that we spend around $10 billion annually on questionable medical practices; an amount considerably greater than the funds spent on actual medical research.26 In addition, a survey of 126 medical schools in the United States found that 34 offered a course in alternative medicine. In fact, at the insistence of some congressmen on Capitol Hill, the National Institutes of Health established the Office of Alternative Medicine (later changed to the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine) in 1991 to test the efficacy of alternative medical practices. While testing such practices is a good idea, many of the office's investigations have not involved accepted scientific techniques, like double-blind studies and control groups.27 Instead, some rely on pseudoscientific arguments and anecdotal accounts. Therefore, after more than ten years and $200 million in research funding, much of the research sponsored by the office has not been able to validate or invalidate any alternative therapies.28 As Michael Shermer, editor of Skeptic magazine, notes, why should we have a separate office of alternative medicine? All medical practices should be tested with the same rigor. We don't have an office of alternative airlines, which tests planes with only one wing.29

Talking with the Dead

Remember the radio show psychic mentioned earlier? The DJs on a local morning show were completely taken by her ability to talk with the dead. Caller after caller was amazed, and in some cases brought to tears, when they thought they were communicating with a deceased loved one. How does the psychic do it? She asks callers a number of leading questions about how their relatives died, what kind of people they were, what they liked to do, etc. In doing so, she culls information, makes a number of general statements, and then focuses on the ones that hit the mark. She inevitably ends the conversation on a positive note, saying something like, “Your father wants you to know that he's not suffering and that he loves you very much.” When the listeners are asked if her comments were accurate, they typically report how amazed they were by how much she knew about their relatives. So, can the psychic talk to the dead? Let's formally examine the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: Some people can uncover information about a deceased person by communicating directly with the dead.

Of course, to test this hypothesis we have to ensure that the psychic had no way of knowing information about the deceased prior to the reading. History reveals that a number of psychics have perpetrated hoaxes. In some instances, readings have been given for a confederate that was known to the psychic. In others, the psychic's assistants mingle with individuals, gather pertinent information prior to the reading, and then relay that information covertly to the psychic. There are many ways to fake psychic powers.

Since the readings were done by phone, and members of a reputable radio station chose the calls, let's assume that the psychic did not have prior information on the callers. What else could account for her accuracy? The callers definitely felt she knew a lot about their relatives. Does she really have the ability to give callers information about their deceased loved ones that she could not have known otherwise? Let's consider the following alternative hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Some people can uncover information about a deceased individual by using a technique known as “cold reading.”

Cold reading is a technique in which the psychic asks general questions about the deceased until she gets some useful feedback from the subject. When she obtains useful information, she becomes more specific in her comments. If the listener responds positively, she continues with the line of inquiry and comment. If she's wrong, she makes it sound as if she were right. For example, statistics show that most people die of an illness somewhere in the chest area, like a heart attack. A standard technique for the psychic would be something like the following:

Psychic: You lost a loved one. I'm getting a pain in the chest. Was it a heart attack?

Subject: It was lung cancer.

Psychic: Of course, that explains the pain in the chest.

The psychic got the illness wrong, but made it sound as if she was right. Is this what the radio show psychic did with her callers? Exactly! Listening closely, you begin to realize that she asks a number of rapid-fire, general questions. In many cases, the caller doesn't even have a chance to respond—instead, the psychic quickly jumps in and says something like, “You know what I mean,” giving the impression that she was right. When callers respond negatively, she deflects the inaccuracies with a few common ploys. Some of the interactions that I heard went like this:

Psychic: Your father died of a heart condition?

Caller: No, he didn't.

Psychic: Then it must be his sister that's coming through with him.

Or in another case:

Psychic: Was she in a wheelchair?

Caller: No.

Psychic: If it's not her, it's on her mother's side of the family.

When she's wrong about the deceased with whom she's supposedly communicating, she deflects attention by saying she's picking up some other relative that's with the deceased. In some cases, she even had the audacity to suggest that the caller simply doesn't know the truth about what she's uncovering. For example:

Psychic: Who wore the pin striped suits?

Caller: No one.

Psychic: If you don't get what I'm saying, write it down and ask your other relatives.

Or in another case:

Psychic: Where are the twins?

Caller: There are no twins.

Psychic: He says there are twins. Either that or someone lost a baby very young with another one. Ask your mother.

As can be seen, the psychic's technique is to ask a number of leading questions and look for answers where she's on the right track. If she happens to hit one, she pursues it. If not, she deflects her error, attributing it to some other spirit coming through from the other side, or to the fact that the caller doesn't have the knowledge and has to ask his relatives. Invariably, she keeps it positive, with comments like, “Your father has the nicest smile,” “He's with his grandmother now,” and “I'm going to give you a big hug from your mother.” Without fail, the deceased wants the caller to know that he's not suffering and that he loves the caller very much.

So, can cold reading really be the reason that people think they're talking with their deceased relatives? Can we be fooled so easily? A considerable amount of data says that we can. Researchers have known for years that we interpret very general comments as applying directly to ourselves. That is, we have a tendency to accept vague personality descriptions as uniquely describing ourselves, without realizing that the identical description could apply to others as well. It's called the Forer effect.30 Also, you have to remember that people who seek out a psychic are those who desperately want to talk with their loved ones. As we will see, our perceptions can be clouded by what we want to see and believe. Cold reading works because people want it to work. They want to talk with their loved ones, and they don't want to be disappointed. And so, they are inclined to believe, and are therefore more than willing to overlook any errors in the psychic's comments as long as the end result assures them that their deceased relatives are okay and say they love them.

If we truly want to believe something, we'll remember the hits and forget the misses. As an example of this phenomenon, consider a reading that another renowned psychic did for nine people who had lost loved ones. Michael Shermer observed the readings. According to Shermer, the psychic applied a number of standard cold reading techniques, such as rubbing his chest or head and saying, “I'm getting a pain here,” and looking for feedback. In the first two hours, Shermer said he counted over a hundred misses and about a dozen hits. Even with this poor hit rate, all nine people still gave the psychic a positive evaluation. If we want to believe it, we will.31

It's also worth noting that a good magician can do the same thing as these psychics. The difference is, the magician doesn't say he's talking with the dead—he knows it's a trick and so does the audience. In fact, there are articles on cold reading from which you can learn the technique yourself.32 We have to ask ourselves, if psychics can really communicate with the dead, why do they have to question the living to learn about the dead? Shouldn't they just be able to sit back, contact the dead, and convey all the information they're getting directly from the deceased? Asking leading questions of the living should tip us off as to the psychics' real source of information.

So which is the more reasonable hypothesis to accept? Do some people have the ability to communicate with the dead or do they extract their information from the living through cold reading? We can certainly test the cold reading hypothesis because someone can employ the technique and we can gather data to see if people thought they were right. We can also test the communicating-with-the-dead hypothesis, although we have to be very careful in designing the study to make sure that the psychic does not have any prior knowledge about the deceased. As far as simplicity is concerned, cold reading wins out because it doesn't require us to assume that spirits exist and that some people can contact them. In addition, cold reading is consistent with what we already know about how humans form beliefs, while there is no credible scientific evidence for the existence of spirits. The cold reading hypothesis seems like the way to go.

I mentioned above that when we test a psychic's ability to communicate with the dead we have to ensure that he has no prior information about the deceased. That is, he's not conducting a “warm reading.” Warm readings occur when a psychic has the opportunity to overhear or in some way get information from the subjects prior to a reading. Many people believe the psychic readings they see on TV. When watching a show, you often get the feeling that not all of what is said can be obtained by cold reading. Remember, however, you're often watching an edited show, and you don't know what went on prior to the taping. An audience member on one of these shows recently sent magician James Randi the following comment on his experiences.

[The psychic] had a multiple guess “hit” on me that was featured on the show. However, it was edited so that my answer to another question was edited in after one of his questions. In other words, his question and my answer were deliberately mismatched. Only a fraction of what went on in the studio was actually seen in the final 30 minute show. He was wrong about a lot and was very aggressive when somebody failed to acknowledge something he said. Also, his ‘production assistants’ were always around while we waited to get into the studio…. [O]nce in the studio we had to wait around for almost two hours before the show began. Throughout that time everybody was talking about what dead relative of theirs might pop up. Remember that this occurred under microphones and with cameras already set up…. He also had ringers in the audience. I can tell because about 15 people arrived in a chartered van, and once inside they did not sit together.33

Whether that psychic is obtaining information from his audience is an open question. However, examples such as this demonstrate that there are alternative hypotheses to consider before accepting such an extraordinary claim as talking with the dead. In fact, failing to consider alternative explanations is one of the most important errors we make in forming our beliefs. If we open ourselves to entertain alternative explanations, and then select the one that's testable, simple, and consistent with well-established knowledge, we can put ourselves on the right track toward evolving more reasoned beliefs. By using such an approach, many of the weird and erroneous beliefs that we hold would simply fall away. In essence, we need to think like a scientist.