Things are not always what they seem.

—Phaedrus

We like to think that we perceive the world as it actually exists, but the fact is our senses can be deceived. We can actually see and hear things that aren't really there. While this may seem far-fetched, research in psychology and neurobiology indicate that to understand perception, we have to abandon the notion that the image we see is an exact copy of reality. Perception is not just replicating an image in our brain; instead, perception requires an act of judgment by our brain.1

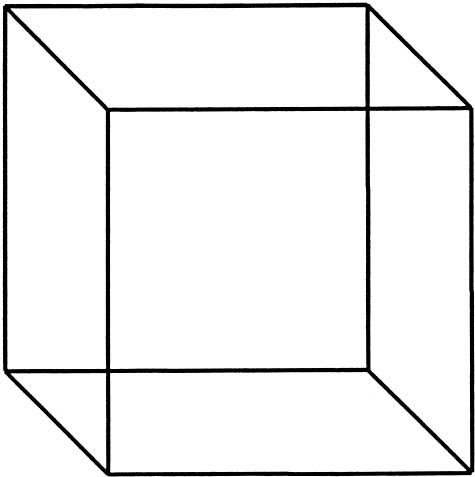

Most of us are familiar with the picture of the cube presented in figure 5. We see the cube as pointing either up or down depending on how our brain interprets the picture, even though the image remains constant on our retina. External reality hasn't changed, but our interpretation of that reality has. Our perception is also affected by the context in which it occurs. A 5' 10” sports announcer looks quite small when he interviews a basketball player, but quite tall when he interviews a jockey.2 Thus, our vision is a constructive process—the simple act of seeing is open to interpretation and judgment.

Figure 5. Cube points up or down depending upon a person's perception.

Of course, our perceptions are often quite accurate (or at the very least, they're good enough). It would be difficult to lead normal and productive lives if they weren't. But when we do misperceive, we can form some pretty weird and erroneous beliefs. Research has found that two factors significantly influence how we perceive the world—we see what we expect to see and what we want to see. That is, we often see things because our prior experiences have led us to expect them, or our desires have led us to want to see them.

SEEING WHAT WE EXPECT

The eye sees only what the mind is prepared to comprehend.

—Henri-Louis Bergson

Read the following:

PARIS

IN THE

THE SPRING

If you're like many people, you read the phrase as “Paris in the Spring.”3 But look closely—the word the is stated twice. We don't expect to find two in a row, so we see only one. As another example, when people were quickly shown a playing card that illustrated a black three of hearts, many of them were sure it was a normal three of hearts or a normal three of spades. Why? We don't expect to see a black heart, so we interpret it to be consistent with our expectations.4 As these simple examples illustrate, we can misperceive our world when reality doesn't match our expectations.

Our expectations can actually make us see things that never happened. For example, when a researcher told people that the light in a room would blink at random intervals, many said the light blinked, even though it never did.5 Other research demonstrates that people can experience electric shocks or smell certain odors when they don't actually exist.6 These misperceptions also occur outside the lab. When a panda bear escaped from a European zoo, people called from all over to say they saw the bear. However, the bear traveled only a few yards from the zoo before it was tragically hit by a train. All of the reported sightings were products of overactive imaginations—people expected to see the bear, and so they did.7 Expectations can lead to hallucinations!

What if you thought that a full moon caused people to act strangely? You would expect to see weird behavior on nights with a full moon, and would likely be on the lookout for such behavior. Many studies have systematically shown that there is no such thing as a “lunar effect”—full moons do not cause abnormal behavior. However, when nurses were asked to note any unusual behavior in their patients during a full moon, those who believed in the lunar effect said they saw more unusual behavior than those who didn't believe.8 If we expect to see something, we'll interpret our world to see it.

Our expectations also affect how we judge others. Consider the following description of a person called Jim:

Jim is intelligent, skillful, industrious, warm, determined, practical, and cautious. Circle the other traits you think Jim is most likely to have (circle one trait in each pair):

Generous———Ungenerous

Unhappy———Happy

Irritable———Good-natured

Humorous———Humorless

When people respond to this task, about 75 percent to 95 percent think Jim is generous, happy, good-natured, and humorous. However, when the word warm is changed to cold in Jim's description, only 5 percent to 35 percent think that Jim will have these traits.9 Other researchers have found that if army supervisors think subordinates are intelligent, they also see them as having better character and leadership ability. If people are thought to be attractive, we typically think they are happier, have a good personality, and produce better quality work.10

Why? If we think a person has a good quality on one dimension, we expect that she will have good qualities on other dimensions. In essence, we attribute characteristics to a person that are consistent with what we already believe about the person. This phenomenon, known as the halo effect, can affect many of the decisions we make concerning others. For example, Jerzy Kosinski was a well-respected author of many acclaimed books. At one point in his career, he wrote a novel called Steps, which won the National Book Award for fiction. Someone retyped the book and sent it with no title and a false name to fourteen publishers and thirteen literary agents, including Random House, who actually published Kosinski's book. Not one of the publishers or agents recognized that the book had already been published—and all twenty-seven rejected it! Without Kosinski's name to create a halo effect, the book was considered to be a fairly mediocre piece of fiction.11

Does something as seemingly irrelevant as the color of one's uniform affect our expectations, and hence our perceptions and judgments of others? We tend to associate the color black with evil. Black Thursday ushered in the Depression. When the Chicago White Sox deliberately lost the 1919 World Series, they were known as the Chicago Black Sox. Psychologists Mark Frank and Thomas Gilovich found that people think black uniforms look more evil, mean, and aggressive, as compared to nonblack uniforms.12 But will this negative perception actually affect our judgments about the people wearing black? Frank and Gilovich analyzed the penalty yards and minutes given to professional football and hockey teams between 1970 and 1986. Amazingly, they found that all the teams in the NFL and NHL who wore black uniforms were penalized more than the average of the other teams. In fact, switching to black can actually increase the penalties given to a team. The Pittsburgh Penguins switched to black uniforms during the 1979 to 1980 season. During the first forty-four games, when they were wearing blue, the team averaged eight penalty minutes per game. For the final thirty-five games, when they wore black, the team averaged twelve minutes per game!

Frank and Gilovich also had football referees and fans view different plays that contained borderline calls. In one play, two members of the defensive team grabbed a ball carrier, drove him back several yards, and threw him to the ground with considerable force. The participants were asked to indicate on a nine-point scale how they would penalize the defensive team for the play. One end of the scale was labeled “cheap shot designed to hurt the opposing player,” while the other end was labeled “legal and somewhat non-aggressive.” Some of the referees and fans saw a video with the players wearing black, while others saw players wearing white. Again, the teams with black uniforms received harsher treatment (average score of 7.2) than the teams with white uniforms (average of only 5.3).13

Our expectations have consequences not only for our perceptions and judgments, but also for our reactions. For example, an intriguing study investigated the impact of expectations on patients' abilities to recover from abdominal surgery. One group of patients was told what to expect from the surgery, such as how long it would last, the type of pain they would experience, and when they would regain consciousness, while another group was told nothing. Those patients who were told what to expect complained less about the pain, required less medication, and recovered more quickly. In fact, they were discharged from the hospital an average of three days earlier!14 Researchers in another study told students that they were drinking coffee with caffeine, when, in fact, it was actually decaf. The students said they were more alert and tense, and even had significant changes in blood pressure.15 While it's not used much now, doctors used to prescribe placebos for some patients.16 As we saw, when a patient expects a pill to work, he sometimes gets better even though the pill has no actual therapeutic effect. It's all about what we expect.

SEEING WHAT WE WANT

While expectations can influence perceptions, our desires are perhaps an even more powerful influence on perception. Why? We have a strong motivation to see things that we want to see in order to maintain consistency in our beliefs. The more we perceive the world as supporting our beliefs, the more we think those beliefs must be true.

A particularly rough football game was played between Dartmouth and Princeton. One of Princeton's star players suffered a broken nose, while a Dartmouth player was carried off with a broken leg. Researchers asked both Dartmouth and Princeton students who started the rough play.17 When the Princeton students responded, 86 percent said that Dartmouth had started it, while only 11 percent blamed both sides. When the Dartmouth students were asked, only 36 percent said Dartmouth started it, while 53 percent said both sides. The researchers then had other students watch a film of the game and write down any infractions they saw. While Dartmouth students saw about the same number of penalties on each side (averages of 4.3 and 4.4), Princeton students saw 9.8 infractions for Dartmouth and only 4.2 for Princeton. All the students saw the same game, yet they saw very different things.

In a similar vein, researchers have asked voters whether the media coverage for a past presidential election was biased, and, if so, in what direction. One third thought it was biased, and of those, 90 percent thought it was biased against their candidate.18 Perceiving a negative, as opposed to a positive, bias toward our preferred candidate is so common that it's actually been termed the “hostile media effect.” Other researchers showed both a rigged “successful” demonstration of ESP, and an unsuccessful demonstration, to skeptics and believers. While the skeptics tended to recall both demonstrations accurately, those who believed in ESP tended to recall the unsuccessful demonstration as successful.19 Our desires influence our perceptions.

Since religion is a powerful motivating force in many people's lives, the impact of desires on perception can be especially strong when people are zealously religious. People have traveled from Canada to Houston because they thought the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe could be seen in an ice cream stain on the sidewalk. In June 1997 the virgin was seen in another stain (thought to be either urine or water) on a Mexico City subway platform. So many worshipers made the pilgrimage that the stain was eventually moved above ground to a permanent shrine in order to accommodate the crowds. In 1978 a New Mexico housewife thought that she saw the face of Jesus Christ in a burned tortilla. Thousands came to see her tortilla. Other “miraculous” visions have been seen on everything from the rust stains of a grain silo to the backs of highway signs.20

You may think that such visions are isolated instances, but that's not the case. I'm sure you can find such occurrences where you live. One of our local newspapers recently ran a story that described a number of such instances in my area.21 In one case, a man claimed the Virgin Mary came in through his window and told him to go to Colt Park in Hartford, Connecticut. He went, saw her again, and spread the news. Hundreds have since come to see what they're calling the Virgin of Hartford in the foliage of a thirty-foot locust tree. On a single day about two hundred people were pointing at the tree and exclaiming, “You see her, you see her!” In another instance, in July 1998, over one thousand people went to a house in the nearby town of Greenfield to see statues of the Virgin Mary and Jesus, which appeared to be bleeding. And, parishioners in a Catholic Church in another local town, Ware, started seeing visions of the Virgin Mary after they thought their church was going to be closed.

Are these really spiritual signs? Is it reasonable to conclude that an all-powerful, supernatural being would be communicating with us through tortillas or ice cream and urine stains? Is there a simpler explanation? It is well known that we look for patterns in things, and this pattern seeking can lead to biased perception, especially when the data we see are ambiguous. For example, when the Viking spacecraft photographed Mars in 1976, some people immediately saw a form that looked like a face, and thought that an alien civilization must have sculpted it. But should we believe in the alien civilization, or believe that our own constructive human perception leads us to see things that we want or expect to see. Even our culture can have an impact on our perception. When observing the moon, Americans see a man in the moon, Samoans see a woman weaving, East Indians see a rabbit, and the Chinese see a monkey pounding rice.22 The forms on Mars and the moon are vague, and therefore open to interpretation, especially if we have a preconceived notion of what to see.

Have you seen the picture of the World Trade Center disaster in figure 6? Some people see the face of the devil in the smoke—they say it makes sense because the attack was such a horrendous deed. But if we look hard enough, we'll see many different images in ambiguous stimuli. In fact, it's a common human perceptual phenomenon, called pareidolia. Just lie on the grass on a beautiful summer day and look up at the sky. All kinds of images will take form in the clouds overhead.

Figure 6. Devil face in the smoke of the World Trade Center disaster (reprinted by permission, © 2001 Mark D. Phillips/markdphillips.com. All Rights Reserved).

Our desires also affect how we judge ourselves and others. One of the most documented findings in psychology is that we want to think flattering thoughts about ourselves. A great majority of us think we are more intelligent, more fair-minded, and less prejudiced than the average person (and a better driver, too).23 A survey of one million high school seniors found that 70 percent thought they were above average in leadership ability, while only 2 percent thought they were below average. All students thought they were above average in their ability to get along with others; in fact, 25 percent believed they were in the top 1 percent. The same goes for teachers. A study of college professors found that 94 percent thought they were better at their jobs than the average professor. Furthermore, most of us think that more favorable things will happen to us than to others. We think we're more likely to own a home and earn a large salary, and less likely to get divorced or become afflicted with cancer, as compared to others.24 Of course, these beliefs can't all be true, but our desires lead us to those biased beliefs.

Consider the following study. Psychologist Peter Glick examined two groups of students—one that believed that horoscopes accurately describe a person's personality and another that did not. Each group read one of two versions of a horoscope. In one version, the horoscope was generally positive, saying that the person was dependable, sympathetic, and sociable. In the other group, the horoscope gave negative traits, indicating that the person was overly sensitive and undependable. When asked how accurate the horoscopes were, the believers said they were very accurate, whether flattering or not. On the other hand, those who didn't believe thought the flattering version was accurate, while the unflattering version was not. Also, the people who initially didn't believe in astrology indicated a significantly greater belief after they received the flattering version of the horoscopes.25 We see what we want to see. If we have a firm belief in astrology, we'll see the predictions as accurate. If we initially don't believe, we'll be more inclined to believe if the horoscope tells us something we want to hear.

HALLUCINATIONS

Do you remember the movie A Beautiful Mind that won the Academy Award in 2002? It was based upon the life of John Nash, a brilliant mathematician who won the Nobel Prize for economics. Amazingly, Nash was also schizophrenic. He would have constant visions, seeing aliens and people that didn't actually exist. When asked why he believed in them, Nash said that his hallucinations came to him in the same way that his best mathematical ideas did. They were very real to him, as they are to other individuals with schizophrenia.

We tend to think that only people with mental disorders such as schizophrenia hallucinate. So when someone we consider normal says he saw a ghost or alien creature, we think that maybe there's something to it. However, research shows that otherwise normal individuals can hallucinate at various times in their lives. Ever since the inception of the International Census of Waking Hallucinations in 1894, surveys have indicated that about 10 percent to 25 percent of normal people have experienced at least one vivid hallucination in their lives. That is, they hear a voice or see a form that isn't actually there. Studies show that if sleep is interrupted for a few days during REM sleep (when we dream), we'll start to hallucinate during the day. Hallucinations can also be elicited by emotional stress, fasting, fever, sensory deprivation, and drugs.26

Years ago, neurophysiologist Wilder Penfield demonstrated that when various parts of the brain are electrically stimulated, vivid hallucinations can result. Another neuroscientist, Michael Persinger, has reported that people have out-of-body experiences, a feeling that someone is in the room, and even deep religious feelings when a helmet containing electromagnets is placed on their heads.27 Patients experiencing epileptic seizures in the temporal lobes of the brain can have very intense spiritual experiences. As one patient indicated, he experiences bright lights, a rapture that makes everything else pale, and a feeling of oneness with God. In actuality, there are circuits in the brain that are involved with religious and other supernatural experiences, which may be activated by outside stimulation or seizures.28

A psychological syndrome called sleep paralysis makes people immobile, anxious, and prone to seeing hallucinations like ghosts, demons, and aliens. It's interesting to note that most alien abductee experiences occur when falling asleep, waking up, or on long car drives. We know that we can experience hypnogogic hallucinations, which occur while falling asleep, and hypnopompic hallucinations, which happen while waking up. In these states, individuals experience floating out of their bodies; feeling paralyzed; and seeing ghosts, aliens, and loved ones who have died. There's also a strong sense of being awake during these hallucinations. Remember my ghostly encounter? It's more common than you think. One study found that out of 182 university students, about 63 percent experienced auditory or visual hypnagogic imagery and 21 percent experienced hypnopompic imagery.29

Research has also shown that a small group of individuals (about 4 percent of the population) fantasize a large part of the time. These people often see, hear, smell, and touch things that aren't there, and they also have a decreased awareness of time. In fact, a biographical analysis of 154 people who said they had been abducted by aliens revealed that 132 of them appeared normal and healthy, but had fantasy-prone personality characteristics.30 In addition, many people are extremely suggestible—5 percent to 10 percent of us can be easily hypnotized—and enhanced suggestibility can influence our perceptions and beliefs. You would think that these misperceptions should make us question the validity of personal accounts of extraordinary events. But our penchant for a good story usually wins out.

Thus, our perception is not a one-to-one mapping of external reality. Instead, it's a constructive process that's determined not only by what our senses detect, but also by what we expect and want to see. In addition, we can, at times, experience vivid hallucinations, and can even have collective hallucinations, where two or more people experience the same thing.31 These collective hallucinations can be so powerful that they can actually lead to mass hysteria.

MASS HYSTERIA

In Mattoon, Illinois, in 1944, a woman said a stranger came into her bedroom late at night and sprayed her with a gas that left her legs temporarily paralyzed. The local newspaper ran stories on the Phantom Gasser of Mattoon, and over a nine-day period, twenty-five separate incidents, involving twenty-seven women and two men, were reported to the police. They said the intruder came into their homes and sprayed a sweet smelling gas that left them nauseated, dizzy, and temporarily paralyzed in their legs. After a couple of weeks of investigation, however, no physical evidence or chemical clues were uncovered. Police and newspapers began attributing the experiences to wild imaginations and mass hysteria, and then the reported intrusions stopped.32

Over a two-week period in 1956, twenty-one people in Taiwan said they were cut by a stranger while out in public (termed the Phantom Slasher of Taiwan). Police eventually concluded that any cuts that occurred came from everyday contact in public places that would normally go unnoticed if it weren't for the media coverage. Between March and April 1983, 947 Palestinian residents of the Israeli-occupied West Bank reported fainting, headache, abdominal pain, and dizziness from supposedly being gassed. Medical tests showed there was no gas, and the reports subsequently disappeared. Just recently, as noted earlier, a monkey-man delusion occurred in India. During the first three weeks of May 2001, people around New Delhi reported seeing a half human–half monkey creature with razor-sharp fingernails, superhuman strength, and incredible leaping ability. On May 16 alone, police had forty reported sightings, often from different areas of the city. Two people actually died when they tried to run away from the creature.33

In various parts of Asia, a particularly disconcerting type of mass hysteria sometimes emerges—penis-shrinking panics. Men in some regions become panic stricken by the belief that their penises are shriveling up or retracting into their bodies. As a preventative measure, the men often place clamps or strings on their penises, or have family members hold their private parts in relays until they can get treatment. In October and November 1967, hospitals in Singapore were inundated—Singapore Hospital treated about seventy-five cases in a single day. The panic occurred when rumors were spread that eating pork vaccinated for swine fever triggered penis shrinking. About five thousand people thought that their genitalia were shrinking in the Guangdong province of China between the summer of 1984 and 1985. Another panic occurred in India from July to September 1982. Thousands of men thought that their penises or testicles were shriveling up, and women thought that their breasts were shrinking.34

It sounds funny, so we tend to laugh at the naivete of the Chinese and Indians who believe these things. But we have our own delusions as well. Since the 1730s people in central and southern New Jersey have been seeing a three-to-four foot-tall creature with a head like a horse and batlike wings. In January 1909 over one hundred people in more than two dozen communities reported a sighting. Townspeople stayed behind locked doors, schools and factories were shut down, and posses were formed to find the creature. In fact, the New Jersey Devils hockey team is named after the elusive creature. During the Salem witch trial hysteria of the 1600s, people were put to death. Other forms of hysteria still occur today. In the 1980s, thousands of Satanic cults were thought to be operating in the United States. The cults were supposedly sacrificing and mutilating animals, sexually abusing children, and performing other Satanic rituals. However, the evidence for such widespread abuse was nonexistent. And what about the multiple sightings of UFOs and aliens that pop up from time to time?

In effect, mass hysterias and delusions have occurred throughout the years, where false or exaggerated beliefs are rapidly spread throughout a segment of society.35 Why do they happen? One reason is that our perceptions can be faulty, and when those misperceptions are combined with our inherent suggestibility, weird beliefs can prevail, even when there is no hard evidence.

NEUROBIOLOGICAL PROBLEMS AND PERCEPTUAL ISSUES

Neurobiological research is uncovering many reasons for our misperceptions of the world. It turns out that perception is dependent upon a number of interacting brain functions, and that problems can arise in any one of them. For example, research suggests that there are approximately thirty distinct visual areas in the brain, and that these areas specialize in perceiving different attributes, such as depth, motion, color, and so on.36 If a person experiences damage to the middle temporal area of the brain, she can suffer from “motion blindness.” Such individuals can identify objects, people, and even read books. But if a car is passing by on the street, they see a series of static strobelike snapshots, instead of continuous motion. Pouring coffee for them is an ordeal because it's difficult to estimate how fast the coffee is rising in a cup.

Neuroscientist V. S. Ramachandran and science writer Sandra Blakeslee report on a number of bizarre perceptions that occur because of damage in certain parts of the brain.37 Individuals experiencing these hallucinations are not mentally ill; going to a psychiatrist would be a waste of time. They are rational and lucid, but their perceptions are flawed. For example, people with damage to their visual pathways can suffer from Charles Bonnet syndrome. They are often partially or completely blind, yet they experience vivid hallucinations that seem more real than reality. Author James Thurber was shot in the eye with a toy arrow when he was six years old. Blind by age thirty-five, he started hallucinating brilliant images, which could have been the basis for his outrageous stories and cartoons. One woman saw cartoon characters in a large blind spot that developed in her field of vision, while another saw miniature policemen leading a little person to a tiny police van. Others with Charles Bonnet syndrome have seen ghostly figures, dragons, shining angels, little circus animals, and elves.

Consider the amazing case of Larry, a Charles Bonnet patient. Larry was twenty-seven when he had a car accident that fractured the frontal bones above his eyes. When he came out of a coma he said, “The world was filled with hallucinations, both visual and auditory. I couldn't distinguish what was real from what was fake. Doctors and nurses standing next to my bed were surrounded by football players and Hawaiian dancers. Voices came at me from everywhere and I couldn't tell who was talking.” He slowly improved, except for one amazing problem. He could see perfectly normal in the top half of his vision, but he had vivid hallucinations in the bottom half, where he was blind. When Dr. Ramachandran interviewed him, Larry said, “As I look at you, there is a monkey sitting in your lap.” He said that the images fade after a few seconds, but when they're there, they are vibrant and extraordinarily vivid. In fact, they look too good to be true. As he said, “Sometimes when I'm looking for my shoes in the morning, the whole floor suddenly is covered with shoes,” making it hard to find the real ones.38

The noted neuroscientist and author Oliver Sacks reported on a patient with neurological problems who, during his exam, took his shoe off. When Sacks asked him to put it back on, the man put his hand on his foot and said, “This is my shoe, no?” Sacks said, “No, it is not. That is your foot. There is your shoe.” To which he replied, “Ah! I thought that was my foot.” When he was leaving, he looked around for his hat, took hold of his wife's head, and tried to lift it off to put it on his head, which gave rise to Sacks' famous title for his book The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.39

Our temporal lobes enable us to recognize faces and objects. When portions are damaged, patients can't recognize their own parents. In other cases, patients suffering from Capgras' delusion come to regard their close relatives as imposters. They recognize the face, but feel the person is posing as their parent, brother, or sister. This may result from damage to the link between the temporal lobe and the limbic system within the brain. The temporal lobe recognizes the image (e.g., mother) and then passes it on to the amygdala which determines the face's emotional significance (e.g., mother associated with love). If the pathway to the amygdala is damaged, the person may recognize the face, but not experience any emotion, leading to the belief that the person is an imposter.40

What we see can also be influenced by what we experienced in the past. For example, a man who gained his sight after being blind for most of his life sometimes saw new things only after he could touch them. That is, if he was exposed to a novel item that he had no experience with in the past, he wouldn't “see” it until he felt it, which was how he perceived things most of his life.41 Research indicates that cats raised in environments where they see only vertical lines typically don't perceive horizontal objects, while cats raised in horizontal environments don't perceive vertical objects. If a cat experienced only vertical lines when very young, and was later put in a normal environment, it would walk off the end of a table because it wouldn't see the table's horizontal edge.42

Problems in perceiving the world arise not just from visual perception. Consider the case of phantom limbs. Patients who lose an arm or leg sometimes feel that the appendage is still there. In fact, the phantom limb can cause excruciating pain, which has even led some to contemplate suicide. One physician had a pulsating cramp in his leg caused by Buerger's disease that was so painful he had the leg amputated. Amazingly, and unfortunately for him, the pain continued in his phantom limb! Some patients feel that their amputated hand is extremely painful because they think it's curled in a tight fist, with their fingers digging into the palm of their lost hand. Dr. Ramachandran created a box with a mirror so that if a patient put his good hand in one side, it would appear that the amputated hand was also there. He would tell his patients to put their hands into the box with their fingers clenched into a fist, and then try to unclench both hands. For many patients, the visual feedback from the mirror made them feel that their phantom fist opened up, so their pain was relieved.43

As these cases demonstrate, our perceptions of the world depend upon the complex interconnected neural structures in our brain. At birth, our brains contain over one hundred billion neurons. Each neuron has a primary axon, which sends out information to many other neurons, and tens of thousands of branches, called dendrites, which receive information from other neurons. Neurons make contact with one another at points called synapses, and every neuron has from one to ten thousand synapses. As a consequence, a piece of brain the size of a grain of sand has about one hundred thousand neurons, two million axons, and one billion synapses, all talking to one another. If problems arise somewhere in these neural connections, our perceptions of external reality can be vastly different from reality itself.

IMPLICATIONS

As we have seen, our senses can be fooled. We often see what we want or expect to see, and we can, at times, experience vivid hallucinations. Interestingly, the problems that arise in our perceptions can come from mechanisms that are often very useful to us in coping with the world. For example, seeing what we expect to see frequently serves a very useful purpose. For the most part, things occur as we expect. Cars generally stop at red lights and go on green, and so we've come to expect that they will continue to do so. If we didn't make this assumption, we would have to pay attention to every car as we go through an intersection. You can easily see how we would be overwhelmed with information if we had to attend to everything. Our expectations simplify our lives, and since what we expect to see or occur often happens, those expectations can be quite useful. However, if things don't happen as we expected them to, we can misperceive the world.44

Given our misperceptions, we can't always trust that our senses are giving us an accurate read of reality, which is a main reason why we can't rely on anecdotal evidence when evaluating the truth of a claim. Just because someone said they had an experience with a ghost or an alien, that doesn't provide reliable evidence for their existence. Ghost and alien sightings could be the result of fasting, emotional stress, drugs, hypnagogic or hypnopompic hallucinations, or even problems in the ocular pathways. Remember, Occam's razor says we should accept the explanation with the fewest assumptions. We don't need to assume that ghosts or aliens are visiting the earth to explain people's personal experiences; human misperceptions can easily account for such reports. And yet, given our storyteller history, we continue to place considerable importance upon personal testimonials and stories.

As psychologist Robert Abelson has said, our beliefs are like possessions.45 We buy our possessions because they have some use to us. So it is with our beliefs. We often hold beliefs not because of the evidence for those beliefs, but because they make us feel good. How can we overcome perceptual biases that lead to faulty beliefs? It's difficult, but a good place to start is by asking three questions: (1) Do you want this belief to be true? (2) Do you expect this event to occur? and (3) Do you think you would perceive things differently without these wants and expectations?46 If the answer is yes to these questions, you should be very careful in how you interpret your perceptions of the world.