Ship Fever

[I.]

January 27, 1847

Skibbereen, County Cork

Dear Lauchlin:

Does this find you well, my friend? For myself I am well enough in body but sick at heart: small excuse for not writing sooner. All has been confusion since our arrival. I have been traveling from county to county with two Quaker relief workers, an American philanthropist, a journalist from London, and various local authorities. Matters are worse than I expected.

At Arranmore, in County Donegal, the streets swarm with famished men begging for work on the roads. At Louisburgh, in County Mayo, the local newspaper reports between ten and twenty deaths a day, and I myself saw bodies lying unburied, for want of anyone to dig a grave. In a hut that had been quiet for many days we found on the mud floor four frozen corpses, partly eaten by rats. That same day, a dispensary doctor told me he’d seen a woman drag from her hovel the corpse of her naked daughter. She tried to cover the body with stones.

Does this give you some idea? Here at Skibbereen, I saw in one cabin a man, his wife, and two of their children, all emaciated beyond belief, sitting around a tiny fire and mourning a young child dead in her cradle, for whom they had no way to provide a coffin. In some places, men have constructed coffins with movable bottoms, in which the dead may be conveyed to the churchyard and there unceremoniously dropped. Those lucky enough to be buried at all have no mourners, often no more than a handful of straw for a shroud.

I see no hope of this situation changing; the British Government continue their benighted policies and say they’ve spent vast sums. Yet we hear reports that the people, having eaten their seed potatoes and cattle and horses, are reduced to eating frogs and foxes and the leaves and bark of trees. Dysentery rages among those who eat the unground Indian corn passed out so grudgingly by the Relief Commission. To the complaints of Parliament, that the land lies unworked and that the lazy Irish refuse to fend for themselves, I would only ask that they visit here and see with their own eyes the terrible apathy brought on by starvation and despair. Or let them hear the horrifying silence lying over this land. We travel for miles and never hear a pig’s squeal, a dog’s bark, a chicken’s cluck, or a crow’s caw.

As you might imagine, I’ve been writing articles, the first of which I am sending to the Mercury by this same post. The American with whom I travel has also undertaken to arrange publication of some of these in the New York papers. Anything to counteract the London papers, which are enough to drive one mad. Yesterday I read a column stating that the cause of the “potato murrain” is a sort of dropsy. Others contend that the rot arises from static electricity generated in the air by the puffs of smoke from locomotives, or from miasmas rising from blind volcanoes in the interior of the earth. Always the potatoes; not a word about the ships that sail daily for England with Ireland’s produce, which might have been used to feed the starving.

I wonder what you would make of all this? You are busy, I imagine. But I know you are keeping an eye on Susannah, as promised. Do try to visit when you can, and keep her in good spirits; I expect she is lonely but I cannot be both here and there and I know you will help her understand this. With luck I will leave here in April, but it is possible I may go to London and do what I can to influence matters there. There will be a vast emigration this spring, for which you should prepare yourselves. Forgive my haste and this scattered letter.

AA

Dr. Lauchlin Grant paused, after reading most of this letter out loud to Susannah Rowley. They were in the Rowleys’ handsome house on Palace Street, in the city of Quebec, behind a door carved with a pair of As intertwined with an S. Susannah’s husband, Arthur Adam Rowley, had built the house and arranged for the decoration of that door. So confident was he of his place in the world that he signed everything, even his newspaper articles, solely with those initials.

But even Arthur Adam could not control the weather, and his sitting-room, with its windows still sealed against the Quebec winter, was overheated on this unexpectedly warm day. It was April already; winter had delayed the mail even longer than usual. The letter increased Lauchlin’s discomfort, and he removed his jacket as he finished reading.

He had not read the lines about watching over Susannah, because they would have infuriated her. Nor had he read the part about the corpses devoured by rats. Now, as he draped his jacket on the chair, he spoke two lines that did not exist: Please ask Susannah to forgive me for writing so infrequently to her. She is in my mind always, but I cannot bear to subject her to all I’ve seen.

Susannah made no response, but Lauchlin felt the sweet, easy mood in which she’d welcomed him disappear. Annie Taggert, the Rowleys’ parlormaid, set the tea-tray down on the claw-footed table by the fireplace, and still Susannah said nothing more than, “Thank you.” Only after Annie’s departure did she turn to Lauchlin to ask, “Do you suppose Annie heard you reading that?”

“Annie?” Lauchlin said. “How could she?”

Susannah shrugged. “She hovers, you know. She stands outside and pretends to dust that cabinet in the hall. She’s been with Arthur Adam a long time—I’m still new to her, and she doesn’t entirely trust me.”

“With…me, you mean?” His face grew so hot that he moved toward the sealed window. “Can’t we get this open?” he said, pushing irritably at the latch. At night he dreamed of women he’d glimpsed during the day, and in his dreams their garments fell away, revealing milky skin. But his dreams were no one’s business.

“With anyone, I suppose. She thinks my manners are appalling. She thinks I’ll say something that will prove I’m not a lady.”

That was all she meant, then. He leaned his forehead against the window, but the glass was hardly cool. Then he said, “I’m sorry about the letter—I shouldn’t have read it to you.”

“Why not?” she said. “How else would I know what’s going on? Maybe he’s on his way home already.”

As she paced the room, the sun cast the folds of her blue gown into deep shadow and struck silver highlights on her breast and shoulders and back. These glimmers were her only jewels, other than her wedding and engagement rings—although not born a Quaker, she’d been raised by her Quaker aunt and uncle after her parents’ deaths, and she still dressed simply. And yet, Lauchlin thought, part of her seemed to miss the glitter of her childhood. When he’d entered this sitting-room earlier, he’d found her kneeling before the tea-table, turning over the contents of her mother’s jewel box. The sight of that mahogany box, with its chased silver hinges and rose velvet lining, had frozen his greeting in his mouth. When they were very young, and had lived next door to each other, Susannah’s mother had sometimes let them play with the box on rainy days. The string of pearls Susannah held, and the hatpins—one tipped with cloisonné flowers, the second with an onyx knob—were as familiar to him as his own mother’s earrings and brooches.

“Do you want to put it on?” he’d asked, bending over to touch the necklace.

As he did so he’d remembered her, at age seven or eight, parading around her mother’s dim dressing room while the rain streamed down the windows. Her parents had gone out and the nursemaid who was supposed to be watching them had fallen asleep. Susannah had stuck the hatpins in her pinafore and, because neither she nor Lauchlin could open the clasp, draped the necklace over one shoulder and around the heads of the pins. She’d smiled broadly and tilted her chin, imitating her mother. Later she’d been given some modest jewelry of her own: a ring with a small ruby, which Lauchlin had watched her unwrap at her tenth birthday party; a dainty gold bracelet. And he had chosen, with his mother’s help, a pretty enameled hair-clasp for a Christmas present. Where had those things gone?

“I don’t like to wear them,” she said, dropping the strand back in the box. “But they’re so pretty to look at…remember these?” She held up a dangling pair of coral earrings.

“Of course I do,” he said. “Surely you could wear those? They’re very plain.” Her earlobes were just visible below the wings of her dark hair, which was parted in the center and drawn up in a simple knot. The coral drops would look lovely against her hair and skin, he thought.

She shook her head, but did not object when he crouched across from her and peered into the box. “Your mother dressed so beautifully,” he said. “And that whole house looked like her, somehow—those violet drapes, remember those? I used to think she must have picked them to match her eyes.”

“She might have,” Susannah said. Her own eyes were closer to gray than violet, and were set unusually far apart. They’d made her look oddly adult when she was a girl. Now they made her look girlish. “I wish I could picture her more clearly. Do you ever have times when you can see all the things around your mother, her clothes and jewelry and furniture—but you can’t see her face?”

“Sometimes,” he said.

Then he’d risen hastily, turned his back on her and the mahogany box, and produced the letter that seemed, suddenly, to have soured the afternoon. All because he couldn’t bear to think of the year when Susannah’s parents had died within a week of each other, and his own mother’s life had been extinguished like a lamp within a room he was not permitted to enter. Afterwards he and Susannah had been separated. She’d gone to her aunt and uncle’s house, in the suburb of St. Roch; he’d been shipped off to cousins in Montreal. Throughout those years, and then through his medical training and his postgraduate studies in Paris, he hadn’t seen her.

On his return to the city of Quebec two years ago, he had rediscovered her: grown and married to Arthur Adam Rowley. How had this happened? But the answer was obvious. She was intelligent and beautiful; Arthur Adam was tall and wealthy and clever. And although she had no more dowry than her mother’s jewel-box, her upbringing set her apart from many of the more frivolous young women in the city. Her seriousness fitted well with Arthur Adam’s ambitions. Already he’d made a name for himself as a journalist, despite the fact that he had no need to earn a living. He liked to make crusades in print, and to outrage his peers by taking up the causes dear to Susannah’s adoptive family. Older men predicted for him a career in politics.

Lauchlin had grown fond of him, despite twinges of envy. All that energy and enthusiasm, his warm hospitality and vibrant conversation—no, it was impossible that Lauchlin should resist him. And their growing friendship had meant he could see Susannah easily. He could knock on the initialed door, as he had today, and be sure of a welcome. Just now, though, he felt confused. Was it the information contained in the letter that had upset her? Or the fact that the letter had not been written to her?

“His news made me miserable,” Lauchlin said: both stating a fact and searching for the source of Susannah’s unhappiness. “It’s unbearable, what’s going on over there. And me here, doing nothing—I should be there.” He pressed his forehead against the glass, as if he could push through it to the air.

“It’s not as though Arthur Adam is actually doing anything,” Susannah said. “He’s watching. He’s writing. That’s what he does. Why does he write in such detail to you, and not to me?”

“He’s writing articles that move people,” he said, evading her question. “Move them to send clothes, money, food—that’s hardly nothing.”

“Anyone could do as much…oh, I don’t mean that, I know what he’s doing, how important it is—but I miss him. All the time.” She continued to pace, swishing her skirts against the heavy furniture. “Does he think I wouldn’t be interested? Why can’t I be there?”

“It’s no place for a woman.”

She spoke as if she hadn’t heard him. “Stuck here, sorting old clothes and running bazaars…and feeling you watching me all the time. He asked you, didn’t he? To keep an eye on me.”

“Only the way a friend would ask another friend—to ease his mind, you know. And perhaps to make sure we each have some company in his absence.”

“That’s how you see yourself? As company?”

Was she mocking him? The room was stifling. He had taken great pains, he thought, not to let her know the depth of his feelings for her. He had been friendly but no more than that; well-mannered, discreet. Although it was true he fussed over his clothes when coming to see her. Now he sneaked a glance at the oval mirror hanging from a cord on the wall. Bushy red hair as neat as a pair of brushes could make it in this weather; a flush spreading from his cheekbones across his freckled, blocky nose. His new shirt was handsome enough, but for all it had cost it still bunched at the collar as if made for a smaller, daintier man. He sat and extracted a fat, prickly cushion from under his elbow. Then he flushed more darkly as he caught Susannah’s gaze.

“Vain boy,” she said. She settled herself in a low chair and poured the tea.

“I am not.” But even as he protested he found himself oddly comforted by her tone, which brought back the bickering of their childhood. Once, in the garden behind his family’s house, they had argued for hours over a passage in a book.

She shrugged, spilling tea into her saucer. “I was only teasing.” Then she let out a small, exasperated sigh. “But here I am. And here you are. Both of us wanting to be over there. I wish you’d stuck with your work at the hospital.”

“But the director wouldn’t let me do anything…bleed, bleed, bleed; that’s all he does, and all he wanted me to do.” He reached for more sugar. “You know that.”

They’d argued before about Lauchlin’s unwillingness to continue working at the immigrant hospital supported by Susannah’s aunt and uncle. “You’re as prejudiced as your father,” Susannah had said. In Findlay Grant’s eyes, the cholera that had killed his wife in 1832 had come from the Irish immigrants, and since then he’d never had a kind word for anyone or anything Irish. But Lauchlin’s defection had nothing to do with his father, only with the limits his own research placed on his time. He studied the nature and uses of alkaloids, those active principles isolated from plants. A substance as useful as atropine or quinine might reveal itself to him, if he were diligent. He’d thought Susannah understood the importance of this. She’d seemed to agree when he explained, after his second hospital visit, how he wasn’t really needed there, and how the work disrupted his research.

Now she offered him a biscuit and said, “Of course your own practice keeps you so busy—how is your practice?”

“The same,” he said bitterly. “As you know.” Why was she being so hard on him? His practice was the least part of his professional life, and the part in which he’d most obviously failed. “Hypochondriacs, asthmatics, rheumatics. And few enough of those. If Dr. Perrault had ever told me that a man with my training would have such a hard time finding patients…”

“Perhaps you ought to pay attention to that,” she said. “Perhaps you ought to think about other ways to employ your talents.”

Why were they arguing? All the warmth of their moment over the jewel-box had dissolved into this disagreement, which had surfaced several times since Arthur Adam’s departure. Where Lauchlin had always believed that his dedication to science would serve the world in large ways, Susannah believed in more immediate good works, embracing the recent flood of immigrants as if by doing so she might bring her parents back. During their honeymoon, she and Arthur Adam had investigated the slums of Paris and Edinburgh, and Arthur Adam claimed she’d contributed to his articles. Since he’d left for Ireland, she’d been helping her aunt and uncle gather food and bedding for the sick. But it was not as if Lauchlin had been idle.

“You’ve made your point,” Lauchlin said. “I notice you don’t seem to mind living in this fine house, though. Even if you’re too good to wear a necklace.”

Immediately he was ashamed of himself; she had lost both parents, where he had lost only one. And the oil portraits in their gilt frames, the piano, and the table with the claw-feet grasping marble spheres were not her choice. Once, when the three of them had been playing whist with another of Arthur Adam’s friends, the friend had complimented Susannah on the new Turkey carpet and she had said, “Arthur Adam picks out everything—congratulate him.” A silence had fallen across the card-table, but later she and Arthur Adam had stood arm in arm at the front door, waving good-bye to the two single men.

“I’m sorry,” Lauchlin said. “I know you wish I was more like your admirable husband.”

He’d meant to be sarcastic, but to his horror she didn’t disagree. “So do something,” she said. Her handsome hand, flicking the air in a furious gesture, knocked her cup to the floor.

And at that, so discouraged and disheartened was he by both her attitude and Arthur Adam’s letter—Arthur Adam, brave and noble, off doing all that he ought to be doing himself—that he set down his own cup and left, his jacket tossed over his arm and the afternoon completely spoiled.

Annie Taggert watched Lauchlin leave. She had overheard most of this conversation; she had also, as Susannah suspected, listened to him read Arthur Adam’s letter. But the letter didn’t keep her from wishing the emigrants arriving here would all stay home. They were like Sissy, she thought. She bustled back into the sitting room and swept up the fragments of broken china while her mistress stared out the window. Too pathetic to help themselves, more and more of them flooding this country: like Sissy, whom Mrs. Heagerty had hired last fall in a moment of weakness. Filthy and stupid and good for nothing. Making a mockery of the people already here.

Down the stairs she went to the kitchen, balancing the heavy tray and already anticipating all that Sissy would have done wrong in her absence. Annie had left Ireland almost twenty years ago; she remembered her fellow passengers as poor but respectable. Men who found work immediately, on the docks or in the forest, cutting timber. Women like her, who went into service with a knowledge of what it meant to do their part in keeping up a household. Nothing like the new arrivals. She noted a small puff of slut’s wool on the stairs; Sissy, again. And in the kitchen she found Sissy crying as she peeled parsnips.

“What’s with her?” Annie asked Mrs. Heagerty, the cook. “What’s the girl sniffing about now?”

Mrs. Heagerty was filling and trimming the lamps, which marched across the table in tidy rows. The room was fragrant with the pies cooling on the range. “I went across to see Mrs. Mullaney,” Mrs. Heagerty said. “Just for a minute, you understand. And what do I find when I come back? Our lazy girl here, sleeping under the table like a dog.”

“What can you expect?” Annie said. She and Mrs. Heagerty had an old and firm bond; they had both worked for Arthur Adam’s parents for years, in one of the finest houses in the city, before coming here to set up this new household. They knew how things should be done. “The stairs are a horror, you know. You saw the filth she left in the corners?”

“No,” Mrs. Heagerty said. “Really?” They turned to weeping Sissy and shook their heads. Annie piled the crockery near the sink. “Don’t you be smashing these when you wash them,” she warned Sissy. “Mrs. Rowley’s already done enough damage for one afternoon—and the good china, too.” She turned to Mrs. Heagerty. “Swept a cup right to the floor, she did. She was that angry at the doctor.”

“What was he wanting?” Mrs. Heagerty asked.

“He had a letter,” Annie said. “From Mr. Rowley. I heard him read part of it. Terrible goings-on over there. If you could hear the things he writes—a stone would cry.”

“He’ll cry,” Mrs. Heagerty said darkly. “When he gets home. If someone doesn’t have a word with that wife of his.”

“They had a fight,” Annie said. “I think that’ll be the end of our doctor—you should have heard the tone in her voice.”

“He’s a useless creature, isn’t he? I heard from Mrs. Mullaney that whole days go by when he isn’t called to a decent house.”

Annie agreed, although she was not sure what it was she wanted the doctor to do. No one could emulate Arthur Adam Rowley, and the idea of the doctor joining in Mrs. Rowley’s dogooding was hardly better. Annie disapproved of her mistress’s actions almost entirely. Exposing herself to filth like that, walking through low parts of town with only a Quaker woman for a chaperone—no, it was not appropriate. Although it was just what you might expect from a woman brought up so irregularly. Mr. Rowley’s mother would never have done such a thing.

Sissy sniffed. “I heard,” she said, in a quavery voice just audible to Annie.

“You heard what?” Annie said sharply. “Speak up.”

“I heard,” Sissy repeated, “from Margaret—you know, at the Richardsons’—that a patient of his died because of something he did. Mrs. Sewell, it was. She had the dropsy. And Dr. Grant wouldn’t bleed her, Margaret says. She says Mrs. Sewell swolled up like a great pig and died, because Dr. Grant wouldn’t bleed her.”

“You heard,” Annie said angrily. “You heard. You know better than to repeat that sort of gossip.” But to Mrs. Heagerty she said, “What can you expect of a man like that? Learning here isn’t good enough for him, he has to go to Paris, France. Then he’s surprised when he comes back here with his fancy theories and finds no one to welcome him but our generous Mr. Rowley.”

Mrs. Heagerty made a sour face and picked up the first pair of lamps. “And his generous wife.”

On an evening two weeks later, the only lamps lit at Lauchlin’s house were in the kitchen, where he had no place, and in his crowded office. He shared this house with his father in theory, but in fact his father was not around for more than a few weeks a year. In his absence, Lauchlin had let go all the servants but one housemaid and the housekeeper and the housekeeper’s nephew, who slept in the stables and did part-time duty as gardener and groom. Lauchlin could hear them laughing downstairs, by the warm range.

His room was cold. He sat on the floor, in front of the fire, with a glass of Bordeaux beside him and a plate of food congealing on the arm of his chair. Slowly, meticulously, he pried the top from a large crate and began to unpack the shipment of books he’d been awaiting all winter. Henle’s General Anatomy, which he handled reverently and then set on the shelf beside his earlier work, On Miasmata and Contagion. Chadwick’s Sanitary Report, which he placed next to Southwood Smith’s Treatise on Fever. Thick books bound in smooth calfskin, containing knowledge he’d begun to think he would never use.

In Paris, where he’d studied with the famous Dr. Pierre Louis, he had learned to be suspicious of excessive blood-letting and over-zealous purgation and to seek scientific explanations for disease. He had learned percussion and auscultation and how to use a watch with a second hand for the counting of the pulse. In Paris human dissection was legal; he had not had to rely on demonstrations but had explored scores of bodies himself. Here, though—here the doctors were old-fashioned, even ignorant. Although they’d admitted him to the Quebec Medical Society, no one agreed with his methods and no one sent patients his way. His research had yielded nothing so far and his practice was dead. He might be better employed doing almost anything.

Susannah’s right, he thought. I’m useless. Still stinging from her sharp tongue, he’d called a few days after their argument on his father’s old friend, Dr. Perrault, and mentioned his desire to find some way of combining his interests in research and preventive medicine with patient care. To his surprise Dr. Perrault had responded enthusiastically, although he hadn’t had an immediate solution.

“Public health,” Dr. Perrault had said. “It’s the emerging field—think about Mathew Carey’s study of yellow fever in Philadelphia. Or Dr. Panum’s handling of the measles epidemic last year in the Faroe Islands. In his report he proved beyond doubt the efficacy of quarantine and the fact that measles is not miasmatic but purely contagious in character. The most rigorous, mathematical epidemiology and investigation of underlying cause, combined with patient care and social policy—good science combined with good medicine. Or so it seems to me. You might keep your eyes open to opportunities here for similar work. It’s a shame to waste your kind of training.”

The conversation had sent him back to his books and, even more than Susannah’s apparent scorn, had made him think perhaps he should reconsider his direction. He had not gone to see Susannah these past two weeks; no more evenings playing cribbage, no long talks over tea. Since their argument he had felt himself to be a scuttling little creature: a rodent, say. Or a louse. His desk was piled with unpaid bills and he’d have to draw on his father’s account again. The house needed repairs, after this long harsh winter. Gutters needed patching, stonework repointing, the shrubberies were a mess; workmen had to be organized and plans drawn up. He had more than enough time to attend to all this, but the idea filled him with an overwhelming boredom. Surely, surely, this was not how he was meant to spend his life.

He finished shelving his new books and then methodically broke the crate into kindling and stacked the pieces beside the fire. Nothing to do now but face the mail. Bills, a heap of medical journals, some of them from the States; a letter from Bill Gerhard in Philadelphia and one from a Dr. Douglas.

He opened the letter from Gerhard first: the usual list of triumphs and enthusiasms. In Paris, Gerhard had already been established as Dr. Louis’s prize student when Lauchlin arrived, and they’d overlapped just long enough to establish a friendship. Since his return to the States, Gerhard seemed to have done everything that Lauchlin wished he’d done himself. An appointment at the prestigious Pennsylvania Hospital; an enormous practice; an investigation into epidemic fevers that resulted in a series of brilliant papers in which he differentiated typhus and typhoid in terms of their distinctive lesions.

Increasingly I lean toward the theories of Henle, Gerhard wrote, after giving the news of his family. These fevers must be due to some sort of pathogenic microbes; and not, as the miasmatists contend, to noxious exhalations given off by filth. But I have to admit I have had no success in finding these microorganisms.

Lauchlin skimmed the rest of the letter and then put it down, feeling very tired. His twenty-eighth birthday had passed without anyone noticing it but him; perhaps, as Gerhard had once suggested, he should have settled in New York or Philadelphia upon his return from Paris, instead of coming here. He almost burned the other letter unread. A request for money from one of the newly founded medical schools, or an invitation to a dinner honoring a colleague he did not respect; he could not bear one more reminder of his failure to make his mark in this city.

But it was just possible that the letter was a referral, and so he slit the envelope.

May 2, 1847

Grosse Isle Quarantine Station

Dear Dr. Grant:

Dr. Perrault has been in touch with me, about your recent inquiry into the possibility of entering the field of public health. I am writing to ask if you might consider assisting me here at the Quarantine Station for the summer months. Every evidence suggests that the coming migration from Ireland will be extraordinarily large this year. We have news that vast numbers of emigrants began leaving Ireland in February, and I believe we may expect them here within a few weeks, now that the ice has finally cleared from the St. Lawrence.

No doubt you have read in the newspapers the various expressions of alarm by the citizens of Quebec and Montreal. Their alarm is justified, I believe. And likely you are also aware of the recent harsh legislation in the United States, which will almost surely have the effect of turning the bulk of the emigration toward us. However, I have not so far succeeded in convincing Buchanan of the probable seriousness of the situation. I have been granted hardly a tenth of the money I requested for preparations. Nonetheless, I have been empowered to hire several physicians to assist me.

Dr. Perrault has recommended you most warmly, and I pray, if your own business is not too pressing, that you consider joining this important effort. If you can see your way to doing this, I could use you at your earliest convenience. Our small steamer, the St. George, arrives at the King’s wharf on Fridays for supplies, departing Saturday, and is available to convey you. Please let me know your decision as soon as possible.

Yours sincerely,

Dr. George Douglas

[II.]

The island looked like this at first: low and verdant and beautiful, covered with turf and trees. The shrubs growing down to the water’s edge were mirrored in the St. Lawrence, so calm that day that the island seemed to hang suspended above a shadowy version of itself. A huge white porpoise rose, disturbing the silver surface, and gulls dove and then emerged with fish writhing in their beaks. As the St. George steamed past the coast, Lauchlin saw a series of miniature bays, craggy and appealing. Toward the island’s center, where the ground rose, were stands of large trees and a white steepled church. None of these conventional beauties eased the knot in his chest.

He had not called on Susannah to say farewell. Instead he’d sent her a brief, businesslike note, wishing her well in her efforts and telling her his destination. He’d asked that she welcome Arthur Adam home for him, thinking Arthur Adam would be sailing up to the King’s wharf any day, but he had not said, though he often thought: “What if I can’t do what’s asked of me? What if all my training isn’t enough?” She believed he was vain, and she might be right. He could not conquer his fierce desire to be recognized as intelligent and competent.

How tired he was of himself! He thought of Arthur Adam across the ocean, wielding his pen on behalf of the people he met, and he tried to set his self-absorption aside and concentrate on what he was seeing. Something that looked like a fort, something else that might have been the hospital—these disappeared in the trees as the St. George moved on. The island could not be more than three miles long, and was very much narrower than that. So green, so seductively rural. Brown cows grazed, all of them facing him. Parts of the countryside outside Paris had looked like this, offering the same relief from the sights of the crowded city. The view changed as the steamer rounded a point; a small village, and low white buildings near the water that might be the quarantine station. Beyond the wharf jutting into the river at the foot of the village, eight or ten large ships lay at anchor. A number of small rowing boats bustled among them, but Lauchlin could not determine what they were doing.

As the St. George eased alongside the wharf, a slight man in a straw hat came trotting down the planks and prepared to board a boat in which four rowers sat ready. He paused to watch the St. George tie up, and to exchange a few words with its pilot. In their conversation, Lauchlin thought he heard his own name. He smoothed his clothes and hair and took several deep breaths, aware that his hands were trembling. A few seconds later, the man cupped his hands to his mouth and shouted, “Dr. Grant! Dr. Lauchlin Grant!”

“Here,” Lauchlin said quietly; the man was no more than ten feet away.

“Wonderful!” the man said. “Come, come, come! I’m late already for the afternoon rounds, you’d better come with me and see what we’ve got. Three more ships came in at noon.” As he talked he guided Lauchlin off the steamer, down the wharf, and toward the boat where the rowers waited.

“But my luggage…” Lauchlin said. He was tired and hungry and a little queasy, as well as worried about his trunk. In it was everything important to him: his medical books, his lancet and lancet-case, a thermometer, some bandages, and some drugs. Morphine, calomel, ipecacuanha, sulfate of zinc, copper salts, sodium bicarbonate, sweet spirit of nitre, Dover’s powder. Some Madeira and brandy, of course, and a few sets of clothing. The man brushed his hesitations aside.

“Leave your trunk here, someone will take it up—Dr. Douglas arranged a room for you in the village. We’re delighted you’ve come. Just sit here, fit yourself in this corner if you can.”

If this wasn’t Dr. Douglas, who was it? The boat pushed off before Lauchlin had settled himself, and he banged his knees against the seat in front of him. He looked up to find a small, creased hand thrust at his waist. “Dr. Jaques,” the man said. “Inspecting physician. Pardon my manners. All this rush—but you’ll understand when you see. No one expected this. We’re very glad you’re here.”

“Glad to be here,” Lauchlin said.

And for the moment, despite the odd flurry of landing, he was. His last patient, before he closed the office, had been a wealthy neighbor who complained that his liver pained him when he drank more than a bottle of wine at dinner. Clutching the bulging flesh below his ribs, he’d whined like an old man but declined to modify his diet. But here were people, Lauchlin thought, among whom his skills might be useful. Almost surely there’d be dysentery, and perhaps a few cases of ship fever; also all the effects of the long starvation about which Arthur Adam had warned him. He braced himself; this was what he was trained for. Meanwhile he took care to sit with his back straight and his chin set, looking over the shoulders of the men who rowed.

It was several minutes before he noticed the water. No longer clear and blue, it was now streaked with dirty straw in which larger objects were suspended. Something floated past him that looked remarkably like a pillow; then several barrels, a blackened cooking pot afloat like a tiny boat, a mass of rags, and some broken planks. There were corked bottles half-filled with clear yellow fluid the color of urine, and baskets lined with scraps of maggoty food. A soggy bed-tick, still kept afloat by pockets of air in its stuffing, elicited a curse from one of the rowers. Two high-crowned hats spun on the water behind it.

“What are these?” Lauchlin asked Dr. Jaques. “These…things?”

Dr. Jaques was impatiently directing the rowers; they were nearing one of the ships. On the rigging white banners fluttered. It took Lauchlin a minute to realize the banners were tattered clothes, hanging out to dry.

“That’s the way they clean,” Dr. Jaques said shortly. “The captains aren’t idiots, even though the British ones run their ships like slavers. Before they signal that they’re ready for us to come, they tell the passengers that we won’t keep them in quarantine if the steerage looks clean. They bully the passengers into throwing all their filthy bedding overboard, all their cooking utensils, the nasty straw: it gets foul down there—have you seen one of these holds? There are no…facilities, and the floors fill up with excrement and filth. They shovel the worst of it into buckets and heave it into the river before we arrive.” He pushed his hat back on his forehead and rubbed at the damp line there. “Sometimes they knock out the berths and toss the planks as well. If they’re healthy enough, they’ll scrub out the place with sand and water, maybe throw on a coat of whitewash. If you didn’t know better, you might think they’d sailed over under reasonable conditions. But you’ll see for yourself—although if this ship is anything like the ones that came in last week, you won’t find much cleaning’s been done.”

Lauchlin nodded, as if this were no less than what he’d expected. He stared at the floating filth and fought down the bile in his throat.

The next half-hour passed in a flurry that left him dumbfounded. On the deck, and then to the captain’s cabin; Dr. Jaques barking out orders and questions. Was there sickness on board? What kind? How many passengers dead and buried at sea? Any dead as yet unburied? How many patients now? The captain, Lauchlin saw, looked as confused as himself. Dr. Jaques had a tablet of paper, on which he scribbled the captain’s answers to his questions. He passed the captain a small book: “Directions,” he barked. “This will explain our procedures. But you must not expect everything to go as stated here. We have room for 150 patients in the hospital, and already we’ve 220 there. No beds. No beds, you understand—we’re building a shed, but we’re dangerously overcrowded already. We’ll do what we can. We’ll take some, the worst cases. The rest will have to be cared for on board until we make other arrangements. The hold, please.”

And then he was trotting back along the deck and down the hatch into the hold, Lauchlin at his heels. The smell was staggering. A single oil-lamp hung from the ceiling, and in the dim light Lauchlin saw the stalls and the narrow passages between them. Within the stalls were rows of bare berths stripped of their bedding and hardly more than shelves. In an open area, scores of unshaven men and emaciated women huddled together, some weeping. Children lay motionless. An old man sat on the floor, leaning his back against a cask and gasping for breath.

Dr. Jaques stopped beside the first berth in which a passenger was lying. “There is sickness here,” he said to Lauchlin.

Lauchlin gaped; did the man think him a fool? Dr. Jaques felt the young man’s pulse and examined his tongue, then gestured for Lauchlin to do the same. Lauchlin shook his head and stepped back, now seeing as his eyes adjusted to the light all the other people collapsed on the bare boards. They shook with chills, their muscles twitched, some of them muttered deliriously. Others were sunk in a stupor so deep it resembled death. On the chest of a man who had torn off his shirt, Lauchlin could see the characteristic rash; on another, farther along, the dusky coloring of his skin.

“Ship fever,” Dr. Jaques said, and headed quickly back up the ladder.

“Typhus,” Lauchlin said, behind him. “We’ll have to find beds for them at once…”

But Dr. Jaques was thrusting more papers into the hands of the mate, with instructions to have the captain fill them out by the following day. “We’ll send a steamer for the healthy,” he said. “As soon as we can. I’ll be back to inspect them before we load. I’ll write an order to admit ten of the patients to the hospital, but the rest will have to stay here for another few days.”

Before the mate was finished protesting, Dr. Jaques had returned to his boat, with Lauchlin reluctantly following. “Nothing else to do,” Dr. Jaques told Lauchlin. “Nothing. You’ll see why when we get back to the island.”

The second ship they boarded, a brig, was not quite so bad as the first; the passengers well enough to stand had cleaned and dressed themselves and were waiting on deck to be reviewed. They were very disappointed to learn that they were not to be carried immediately to Quebec or Montreal.

“Tomorrow,” Dr. Jaques told the captain. “Or the next day. We’re very short-handed just now.”

Meanwhile Lauchlin could see that the water-barrels were nearly empty, and the pig-pens and chicken-coops silent. The passengers’ beds had been thrown in the river. He said, “But…” and clutched the papers Dr. Jaques had asked him to hold. He said, “I’m sorry,” to the sputtering captain; then he said nothing. It was impossible to guess the right things to say or do.

The third ship they visited, a bark, was very much worse. The captain had died four days before reaching Grosse Isle, and the mate who’d brought the bark the rest of the way was sick himself, only capable of responding in broken phrases to Dr. Jaques’s questions. They had buried a hundred and seven at sea, he said. Or perhaps it was a hundred and seventy. When they ran out of old sails to use as shrouds they’d slipped the bodies into weighted meal-sacks and tipped them over the bulwarks on hatch-battens. There were many sick below. Along the rails a crowd stood pale and thin, some propped up by their companions but pretending desperately to be well. Two boys caught Lauchlin’s eye—still in their teens, dark-haired and gaunt, leaning against each other’s shoulders for support. Perhaps they were brothers. When they saw Lauchlin looking at them, they looked at the deck.

He said nothing to them, nor to Dr. Jaques; by now his silence seemed unbreakable. There was no way to make sense of this situation. From the deck he saw the green island, the sun glinting on whitecaps, the hills lolloping gently toward the horizon from the river’s edge. And for a moment he thought longingly of his clean, empty office at home.

Into the hold: again, again. Already Lauchlin felt as though he knew that place by heart. The darkness, of course; and the rotting food, and the filth sloshing underfoot. The fetid bedding alive with vermin and everywhere the sick. But a last surprise awaited him here. He inched up to a berth in which two people lay mashed side by side. He leaned over to separate them, for comfort, and found that both were dead.

He vomited into a corner, a place already so filthy he couldn’t make it worse. Then he scrambled up the ladder and hung breathing heavily over the rail. It was too much, it was impossible. He would go home at once, on the next steamer out, and when Susannah chided him he would tell her that this was not what he had bargained for: this was madness, he could be of no help. All the instruments he’d learned to use, all his theories and knowledge were worth nothing here. These people needed orderlies and gravediggers and maids and cooks; not physicians, not science. They needed food, sleep, baths, housing, priests.

Dr. Jaques came to fetch him. “Feel better?” he asked, offering a clean handkerchief. “Don’t be embarrassed—I did the same thing when I started. Everyone does. Dr. Moorhead fainted six times his first day out on the ships. Up and down like a Jack-in-the-box, you never saw a face that color in your life. You’ll be all right. Are you ready?”

He turned and backed down the companionway again, looking expectantly over his shoulder at Lauchlin. Lauchlin spat into the handkerchief one last time and steadied himself. Of course he had to follow Dr. Jaques. He was young, strong, healthy. “You’ll get used to it,” Dr. Jaques said, as the darkness folded over their heads. “They’re not all this bad. This is among the worst we’ve seen.”

Among the worst? What could be worse? Lauchlin turned his eyes from one impossible sight to the next, determined to follow Dr. Jaques’s lead. Dr. Jaques gave orders to some sailors behind him, sending one up on deck to recruit more hands and another back to his boat, with instructions to have him gather up whatever other boats were available.

“You men,” he said to the sailors who’d reluctantly come to join them. “You’ll have to help here—we have to get these bodies off the ship. There’s a sovereign in it for each of you who’ll do a good hour’s work.”

Even with that vast sum, there were not so many volunteers; he checked the passengers up on deck, but among them not one was strong enough to help. The remainder hunched in corners or lay on the planks, shivering and dull-eyed. Lauchlin shed his coat and rolled up his shirt sleeves and did as Dr. Jaques directed. He and Dr. Jaques and the sailors formed a chain, as they might to pass buckets of water for a fire. Down the length of the hold, up the ladder, across the deck to the rail.

There were boathooks involved at the ladder, where the bodies had to make a transition from one level to the next, but Lauchlin could not bear to look at them or even admit their existence. No thinking, he told himself. Follow orders, do what’s needed. He would not, until this task was done, see the ropes binding bodies into bundles and then lowering them, heads and limbs dangling, down the side of the ship to the boats waiting below. Had he seen that journey’s last stage, he might not have been able to move, as he did, from berth to berth, gently turning bodies and closing eyes and lifting shoulders as Dr. Jaques lifted legs.

The eighteenth body he lifted and passed was a young woman, hardly more than a girl, who’d been dead for several days. Her feet were black and twice their normal size. The nineteenth body, almost crushed beneath the eighteenth, was another young woman, perhaps twenty-two or three. Her hair was very long, matted around her face and neck. Lauchlin had to move the hank aside before he could grasp her shoulders. His mother had had hair like this, black and heavy and perfectly straight; for an instant, as he touched it, he could see her face. It took him a second to realize that this woman’s flesh was still warm. As his fingers tightened reflexively on her arms, she groaned.

The woman, whose name was Nora Kynd, heard Lauchlin’s voice without at first understanding his words. In her delirious half-sleep, she was reliving the last week of her passage.

She had fallen sick before they reached the Gaspé Peninsula and Anticosti Island, and although she had not taken to her bed at first—there being no bed for her to go to—she had spent the days after they entered the St. Lawrence reeling between the deck and the hold. On deck she’d stared at a cabin passenger, neat and clean and well-fed, sketching the sights on a pad. An impossible figure, a gentleman. From the corner where she huddled, he’d looked like someone who might save her, had he cared to. But he was occupied with other interests.

Whales! she heard him exclaim to the mate. She’d seen them too, a great swirl of water near the side of the ship breaking to show a glossy flank. Beluga whales, the gentlemen said; his pencil moved on his pad. A shark followed in their wake with great constancy, and the gentleman mocked the ship’s carpenter who said it was a certain harbinger of death. He pointed out sturgeon, green with white bellies—she saw them too, or thought she did, and that was the name he gave them. Eavesdropping on his conversations, she learned the names for porpoises and eels in the water and the white birds overhead. She needed no help to appreciate the green hills and stony cliffs and farms along the water. They’d been right to come, this was paradise. It was curious, though, that the gentleman never noticed her.

She stayed on deck when the weather allowed, even though she was very ill; anything was better than the crowding and smells below. One of her brothers brought her water, the other what food he could. She knew the younger, Ned, had already been caught once begging extra water from the sailors’ scuttlebutt. She worried about them, distantly, and prayed they’d stay healthy. But a deadly calm had come over her, a calm she knew came from her illness. Shivering that swept her body in waves, scarlet spots on her shoulders—she had fiabhras dubh, the black fever, like all the people dying below. At home she’d taken care of fever patients, using the tricks she’d learned from her grandmother. But now her tongue had gone quiet in her mouth, she could no longer groan, she could not resist. She was filled with a gentle resignation that, during her brief lucid moments, she recognized as fatal.

Where was it she’d finally collapsed? Near the galley, she thought. Somewhere in that crowded space around the range of cooking fires, hemmed in by the cow-house and the poultry pens and the pigsty and the heap of spare spars. Down she’d gone, with the sky overhead rushing down to greet her. Afterwards came a long stretch of darkness and a tormenting thirst. A weight arrived, pressing and crushing as the ship heaved in what must have been a storm. Feebly, during brief waking moments, she had tried to push the weight aside. The weight was first warm and then cool and then cold and very heavy. She woke when the hatches were open, letting in a pale streak of light, and found herself staring into the open eyes of Julia McCullough. They were filmy, like the eyes of a fish.

She’d tried to push Julia’s body away but she had no strength. Her brothers were up on deck where she’d ordered them, knowing her death crouched beyond the bulkhead and unwilling for them to witness it. How they had wailed when she’d said goodbye to them!

But here were sounds, and a sense of the boat motionless beneath her in a way she’d never thought she would feel again. A man spoke above her and then lifted Julia’s body away. He touched her hair, gentle hands. She wanted to thank him but was unable. He touched her shoulders, released them suddenly, made a strangled noise she could not interpret, and then brought his face down so close she could feel his breath.

“You’re alive!” he said.

With a great effort she opened her eyes. Red hair, blue eyes, a nose like a chunk of granite. Almost like someone from home. “Don’t worry,” he said. “Don’t worry—I’m taking you to the hospital.”

Another man appeared behind the first man’s shoulder; then both straightened out of sight. She heard the sounds of argument, then nothing. And so when Lauchlin carried her up the ladder himself, she was not aware of Dr. Jaques’s angry objections, nor of her brothers who broke into sobs as they saw what they assumed was her body draped across a stranger’s arms. She did not hear their joy when they rushed to her and found her miraculously alive, nor their anguish when one of the doctors, red-faced and truculent, pushed them aside and denied them entry to the island.

The two boys who’d staggered over to Lauchlin were the pair who’d first caught his eye upon boarding; they were brothers, Ned and Denis Kynd, and this woman he was carrying was their sister Nora, whom they’d believed dead.

“Let us come with her,” Denis begged. “We’ll do anything—carpentry, cleaning, tending the animals. You wouldn’t have to pay us. We could help take care of her.”

Lauchlin started to say, “Of course,” but Dr. Jaques stopped him. He looked straight at Lauchlin, ignoring the boys.

“I’ll admit her to the hospital,” he said. “Even though there’s no room—let it be on your head, you can find a place for her. I said ten patients from this ship, and I meant it. There are others sicker than her. But I absolutely refuse to let these two on the island. They’re almost healthy, except for the dysentery, and they’re going on the steamer that leaves for Montreal tomorrow. If they stay here they’ll die. If they land on the island, there’s no telling what will happen to them.”

“How can you separate them?” Lauchlin said. It seemed to him, just then, that he had never met a more callous man. But all his pleas were no use; in the end Dr. Jaques simply pulled rank. “You’re the junior doctor here,” he said. “Have you managed an epidemic before? Have you ever seen more than an isolated case of typhus? Do you have any idea what’s going on?”

“No,” Lauchlin said. “But…”

“I didn’t think so.”

The last thing Lauchlin saw of the bark was the Kynd brothers hanging over the rail and wailing, not at all comforted by the thought that they, almost alone among the bark’s passengers, would be on a steamer headed upriver tomorrow. Why hadn’t he thought to give them some money? He could not imagine what would happen to them after their journey—although they didn’t have fever they were half starved, penniless, hardly more than children and deprived of their sister. He could not imagine what would become of any of these people. Already, despite his fury and confusion, he’d begun to doubt the wisdom of singling out a single patient to save among the hundreds needing help. By now he’d figured out the mission of the other boats plying between the ships and the island.

Some carried the patients lucky enough to be admitted to the hospital by Dr. Jaques’s orders. From his own boat, with Nora Kynd unconscious in the bow, Lauchlin could see sailors lifting the helpless patients from other boats, dragging and carrying them over the rocks in the direction of the hospital he still hadn’t seen. The remaining boats carried the dead.

The dead from the bark, where there’d been no supplies, were dropped on the nearest beach and corded like firewood to await the men who’d build their coffins. Others, from ships where a few healthy passengers remained, were wrapped in canvas or rudely coffined in boards torn from their berths. The boats carrying those bodies formed a long line, moving around the projecting tip of the island to the burial ground. In some a mourner accompanied the corpses, but in most only the rowers were alive. A lone boat moved in the opposite direction, carrying four priests with their black bags, ready to don their vestments and visit the holds.

They would be more welcome aboard the ships than him, Lauchlin thought; perhaps more use as well. And yet despite his despair, and his first sight of the hospital surrounded by piles of coffins, the tents lurching upright as the sound of hammering filled the air; despite the glimpses he could hardly bear to register of a panic equaling that on the ships; still he could see that the island was as beautiful as his first glimpse had promised. Above the beach a mass of wild roses bloomed furiously.

Nora was taken from him, to the hospital he glimpsed in the distance. A man whose name he didn’t know led him, on Dr. Jaques’s order, to the place where Dr. Douglas lived. The road from the village wound through a beech grove in full leaf, casting a solid shade that cooled him. Bewildered, exhausted, Lauchlin followed his guide to a green lawn stretching before a cottage perched at the water’s edge. A dog rushed from the rhododendrons, barking and barking as if prepared to bite, veering off only when Lauchlin’s companion seized a stone and threw it. Lauchlin brushed his clothes off as best as he could while his companion knocked on the cottage door. A small man, tidy despite his shirtsleeves, opened it. His hands were full of papers and more littered the table behind him and towered in stacks on the chairs.

“Dr. Douglas,” said the nameless guide. “I’ve brought you Dr. Grant.”

Dr. Douglas said, “Where have you been?”

[III.]

June 2, 1847. The weather continues terrible; today it rained again. The men finished building the first of the new sheds but the hammering continues: coffins, sheds, more coffins. I have not been sleeping well. Already the hives that occasionally plagued me in Paris, when I was overworked, have broken out along my upper arms. Another letter from Arthur Adam arrived, dated March 4 and forwarded from the city—he includes this news, which I suppose he meant as a warning:

There is a great deal of fever here now. We see two types: the so-called yellow fever, which the natives call fiabhras buidhe and some of the doctors call relapsing fever; and black fever—fiabhras dubh—which you will know as typhus. You might warn your colleagues who see this class of patient that they should expect to see some cases among the emigrants headed your way. Yesterday I heard a story, which I could not confirm, that the emigrant ship ‘Ceylon,’ sailing with 257 steerage passengers, lost 117 to fever on the voyage. Have you any evidence yet of this?

One of his articles appeared in the Mercury a few days ago. Lots of details, very elegantly written.

Three days after my arrival, another seventeen ships anchored. All of them had fever. By May 26 there were thirty ships, and by the twenty-ninth, thirty-six: a total of some 13,000 emigrants, many of them sick. Yesterday I stood on the wharf and counted forty vessels stretching down a St. Lawrence so befouled I could hardly see the water. We have in excess of a thousand fever patients on the island: more than 300 jammed in the hospital, the rest in sheds normally used to detain passengers during their quarantine, in tents, and even in rows in our little church. More than this number lie sick in their ships, waiting for help we are helpless to provide. At the far end of the island, the quarantine camp for the “healthy” is in fact also full of the sick. Yesterday a boy died there, without ever having seen one of us. First name Sean, last name Porlack? Pallrick?

June 8, 1847. Muggy and hot. Dr. Douglas is a good man, but nothing he does makes more than a dent in this situation. There are more than 12,000 people on this island now, many without shelter and almost all short of food. Dr. Douglas has applied to the government for a detachment of troops to be stationed here, to preserve order. Buchanan, the chief emigration officer, has obtained some tents from the army. These are not much comfort during the rain and hot weather. My feet are swollen and the skin is peeling between my toes.

This day Dr. Douglas sent an official notice to the authorities in Quebec and Montreal, warning that an epidemic is bound to occur in both cities. Any reasonable quarantine procedures, as the medical profession would recognize them, have become impossible to enforce.

We now allow the ‘healthy’ to perform their quarantine on board, as there is no room for them on the island. They are detained aboard for fifteen days, after which they are shipped upriver. We released over 4,000 last Sunday—truthfully, many were already sick, and many more carry the seeds of contagion. We received word yesterday that three ships loaded with emigrants and bound for this port were wrecked in a late snowstorm along the Cape des Rosiers. All aboard were lost.

Some eighty vessels have now made their way to us. Several among them fly their ensigns at half-mast: captain, chief mate, or other officer having succumbed to fever. Deaths among the passengers are almost past counting. I see I have not yet mentioned the death of Dr. Benson. Arrived here from Dublin on May 21, just before me, he volunteered his services in hospital. After contracting typhus, he died May 28: a kindly, thoughtful man. We are fourteen now, on the medical staff. Twice our number would hardly be enough.

I have hardly seen Dr. Jaques since my arrival. He spends every minute shuttling among the ships. The sick he can do little for—many lie for days without any medical attention. The ships’ captains, crew, and passengers despise him for his failures, but I can no longer do so. He—we, I—separate the sick from the healthy without regard for family ties; we have no choice. Yesterday a young Anglican clergyman, newly arrived, chided me for dismissing a fully recovered young man from the hospital while detaining his still fevered wife. “Where is that man to go?” he said indignantly. “You know they’re sleeping on the beaches now, without any covering. Do you expect him to go upriver without his wife?”

“Where would you have me put him?” I asked. “He’s well, and the ships are full of sick who need the beds here.” Of course I heard the echo of Dr. Jaques’s rebuke to me in my words. And on the clergyman’s face I saw an expression that must have once been on my own.

Why, then, does Dr. Jaques continue so unfriendly toward me? Three young doctors from Montreal assist him at his task, but I am not allowed to join them and he never looks at me squarely. Dr. Douglas says I am needed here on the island more than on the ships; he is courteous to me, but not much warmer than Dr. Jaques, and I cannot help believing that I am under some sort of suspicion because of my behavior that first day. Not because I vomited or fled the hold: Dr. Jaques told the truth there, every new doctor responds this way. But because I argued with Dr. Jaques about the disposition of the Kynd brothers, because I insisted on bringing Nora here…was it what I said? Or only that I raised my voice to say it, that I shouted and showed myself to be excited?

I have not once since then left a patient’s side when I was needed. I have not once raised my voice in anger. Mrs. Caldwell burned the cuff of my last good shirt, and I said nothing.

The days pass swiftly, each worse than the one before. Already those here to help the patients begin to turn into patients themselves. More Catholic priests have arrived, from Quebec and Montreal. They travel among the ships with Dr. Jaques, giving what comfort they can. Mostly they administer last rites. One, who returned to the village this evening for dinner, looks to be on the verge of fever himself. The miasma arising from the holds of the ships is so dense that he swears it is visible as a stream of tainted air flowing from the hatches like a fog.

June 14, 1847. The weather continues extremely hot. Nora Kynd is recovering—a miracle that anyone should get better under these conditions.

We have almost no equipment. The hospital was overcrowded even before my arrival; we were given, to meet the influx of thousands, exactly fifty new bedsteads and double the quantity of straw used in former years. The new sheds are no more than shacks and what bedding there is has been placed directly on the ground, as there are no planks on which to lay it. Within days it becomes soaked and foul. The old passenger sheds are the worst of all. Here the berths are arranged in two tiers; several patients are jammed in each berth and invariably it seems to happen that the top berths are given to patients with dysentery. The filth and stench are indescribable.

We have very few nurses—how could this surprise anyone? For three shillings a day they are obliged to sleep amongst the sick and have no private rooms where they may rest or change their clothes. They receive the same food as the emigrants, and are granted no time in which to consume it; I see them crowded outside the sheds at mealtime, gobbling on their feet. It will be a wonder if they do not all succumb to fever. Dr. Douglas asked one of the priests to try to persuade some of the healthy passengers to volunteer their services. Even with the enticement of high wages, very few came forward.

Buchanan has issued an order compelling all the servants at present on the island to remain, until and unless they can provide substitutes for themselves. They are surly, nearly useless, retained as they are against their will; they taunt us, trying by outright misbehavior to provoke us into dismissing them. The woman whose job it is to bring afternoon tea to me and my assistants yesterday spilled it deliberately. She looked me right in the eye as she let the tray tip, the teapot slide forward and crash to the ground. Her name is Millie. If I dismiss her, there will be no replacement. There is talk of freeing prisoners from the city jail and bringing them here to care for the sick. Meanwhile the police appointed to maintain order wander the streets drunkenly.

On occasion I have longed to join them. I long for many things. Privacy, quiet, sleep, decent food. Susannah. I wonder how she is. If it were not for her and my own fear of appearing weak, I might run away.

Nora is in the little church, which has turned out to be the best of our makeshift hospitals—the bedding stays dry because of the floor, and the large windows allow for good ventilation. Last night, when I stopped by to see her, her skin was cool, her pulse almost normal. She asked me where her brothers were and I told her they were fine. What use would there be in telling her that they have already been carried against their will at least as far away as Montreal? In fact they may be much farther, as we hear that the residents of that city are in an uproar about the condition of the emigrants, and have insisted on pushing many on to Kingston and Toronto.

When I woke this morning, I could not at first remember where I was. I heard hammering—a sound one never escapes from here—and the sounds of carts rattling down the streets, and for a moment I was back at home during the season my mother died. Then I heard the bustle of Mrs. Caldwell below, fixing breakfast for the crowd of us. Besides Dr. Stephenson and Dr. Holmes and Dr. Black, with whom I have been working and who share the second floor with me, we were joined two days ago by Dr. Pinet of Varennes, Dr. Malhiot of Vercheres, and Dr. Jameson of Montreal—a quiet, well-bred man with a passion for bees and some real understanding of physiology. Mrs. Caldwell has arranged makeshift beds for them in the attic above me. Rapidly, this is coming less to resemble a boarding house and more one of the sheds where our patients lie. The other physicians are similarly lodged, the attendants and servants lodged much worse. Food is becoming a problem for us, as it is for the passengers. The beef and mutton Mrs. Caldwell can obtain are sometimes inedible. She bakes, and so we usually have bread except on the days when the local storekeeper runs out of flour. We hear that the bread his wife turns out in large batches is purchased at exorbitant prices by the ships’ crews, who are running low on provisions.

June 19, 1847. Still hot; thunderstorms. Today, after finally obtaining Dr. Douglas’s grudging permission, I moved my books and supplies to this closet at the front of the church we’ve converted into one of the hospitals. I will continue to sleep at Mrs. Caldwell’s, and have left most of my clothes there. But now I have one small space where I may read and write in relative silence, without the snores and sighs and throat-clearings of Mrs. Caldwell’s.

A number of my patients are arrayed in rows in the main chapel. Nora Kynd lies among them; she continues to improve. Last night she felt well enough to walk about, and as she begged for some fresh air I escorted her out to the porch, bringing two chairs from inside. She regrets the loss of her hair, which had to be cut during the worst of her sickness.

She is from a rural area in the west of Ireland, not far from where Arthur Adam traveled. In the years just before the murrain struck, when the potato crops were so abundant that no one knew what to do with the surplus, potatoes were stacked in heaps in ditches and fields, buried in huge pits and never used, fed to animals, plowed back into the fields. The famine is a punishment, she believes, a scourge come from God to punish her people for waste. I was not able to convince her that this was a superstitious view, that the blight is a biological phenomenon and unrelated to the earlier surplus.

Most of her family is dead now; only she and the two brothers I saw on the bark survive. Her account of their passage differs in detail but not in substance from the stories I’ve heard again and again this month. Later she backtracked and spoke of fever in her village. She sometimes refers to the fever as an droch-thinneas, which she tells me means “the bad sickness”; sometimes she refers to it by the name Arthur Adam used, fiabhras dubh. Of course it’s difficult for me to be sure, but based on her description of symptoms I would guess that in most cases her neighbors suffered from typhus, as defined by Gerhard and Wood. Some clearly had famine dysentery as well—she described the ground outside the huts of the sick being marked by clots of blood. Her grandmother was an Irish nurse—“nurse Gaelacha,” Nora called her; a local woman with some knowledge of traditional remedies. She seems to have practiced something very close to the quarantine procedures we’ve tried and failed to employ here.

At first I tried to stop Nora from speaking of this time, but she wouldn’t stop and I came to believe it was of some help to let her talk. I found it interesting to hear how the disease process manifests itself elsewhere.

“There were houses in the district next to us in which first one person died and then another and another, and all were so weak and sick that none could do anything until the last person died,” she said. “The bodies lay in the houses and the dogs came. When the fever passed by, those neighbors who had come to themselves a bit would go to the houses where everyone had died and find nothing but bones lying there on the floor. The neighbors would gather the bones and bury them and then burn the houses to the ground, so as to burn the sickness out.”

She wept quietly for a while; I went inside and returned with a note pad, a handkerchief, and a small glass of brandy, which choked her when she sipped it but brought a little color to her face. Her skin is remarkably white; I still can’t tell whether this is the result of her illness, or her natural color. Around the irises of her eyes is a fine line which appears bronze in some lights, dark brown in others—normal?

“In my village half the people died, including my parents, two brothers and a sister, my mother’s brother and sister, and many of my cousins. My grandparents, too. But others were spared, because my grandmother on my mother’s side helped them before she got sick herself.”

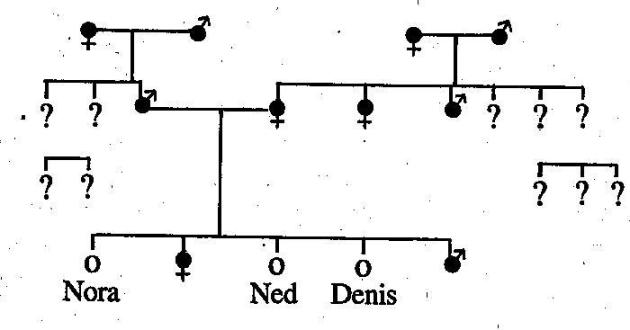

This is what I drew as she spoke. Lines of writing, little arrows and crosses; as she watched me draw she said it looked like a misshapen tree hung with apples:

The circles with the small crosses beneath indicate the women in her family; those with the arrows are the men. Each generation on a separate line. Those darkened represent the dead—grandparents, parents, her aunt and uncle on her mother’s side, her brothers. When I had explained the figure to her, she took the pen from my hand and added to the bottom row an apple I’d missed; then she darkened it. Robbie, the youngest. She found it hard to say his name.

Here is the rest of her story, or as much as I could scribble while she spoke:

“I helped my grandmother after my parents died. Ned and Denis helped too. When we could we took the sick from their houses and put them into huts—bracai, we called them—we made by thatching brambles and rushes over poles against a sheltered ditch. We kept those people separate from the healthy. My grandmother would go into the hut with the sick people, and we would wall up the door with turf and then pass food in through the window, on the blade of a long shovel. Never would we touch the empty vessels she passed back out through the window.

“My grandmother could see the sickness on someone, as good as any doctor could; she knew it was an droch-thinneas by the color of their urine. She did not give the sick a mouthful to eat, but she gave plenty to drink, as much as we could gather and pass through the window. Two-milk whey she gave, when we could get it—very light and sustaining. To make it we boiled new milk and then added skim milk to it. The sick would drink this and also eat the curd. Also she gave the juice of cress and wild garlic, and sheep’s blood if it could be found. When the color of the urine lightened, she would give a single toasted potato. We saved what few good potatoes there were for this use; ourselves, we were eating ferns and dandelion roots and pig-nuts and cresses. My grandmother did not come out of the fever-hut, nor let anyone in, until her patients were completely well.”

When I asked her how she and Ned and Denis avoided the sickness themselves, she said that before they first touched the patients and carried them to the fever-huts, and also before they burned the huts of the dead, they washed their hands and faces in their own urine, to protect them.

“Would you say, then,” I asked, “that you attribute your relative health in Ireland to the strict isolation procedures taught you by this grandmother?”

“Isolation,” she said. When she raised her hand to smooth her hair, it slipped off the shorn ends. “That means making someone to be alone?”

June 20, 1847. Rain, which does not alleviate the heat. Two nurses died yesterday. In hospital we have 1,935 sick, according to Dr. Douglas’s count. Several hundred more sick remain on board their ships, infecting the well.

No sleep at all last night. This morning I saw a dog by the wharf and thought it was a wolf. Why would anyone allow dogs on this island? I have brought blankets from Mrs. Caldwell’s and plan this night to make a pallet here on the floor. The patients cannot be noisier than my fellow medical officers. A number of those working here now have been recruited from the army, and their manner is disagreeably matter-of-fact and hearty.

Nora’s story continues to haunt me. Henle makes the distinction between miasma—the disease substance that invades an organism from the outside; and contagium—the disease substance believed to be generated in the sick organism, which spreads the disease by contact. He argues that the pathogenic matter must be animated, although he has as yet no proof for this. Southwood Smith, in his Treatise on Fever, discounts the theory of contagion in favor of noxious exhalations, or miasmas, given off by filth. Chadwick, Smith’s follower, says dirt is the nurse of disease, if not the mother.

It’s true that on the filthy ships the passengers sickened quickly. Here, the disease seems to spread somewhat slower in those places where the beds are less closely crowded, and the ventilation is better.

But Nora says fresh air has nothing to do with it; she spent all the time she could on the deck of the bark and still sickened. In one of the books Gerhard sent to me is a discussion of an old paper by Dr. Lind, physician to the Royal Navy. Lind contended that typhus is carried not only on the bodies of the sick, but upon their clothes and other materials they touch: beds, chairs, floors. In defense of his views, he cites the death of many men employed in the refitting of old tents in which typhus patients had been cared for. He advocates fumigation (camphorated vinegar, burning gunpowder, charcoal); also a thorough scouring of patient quarters and destruction of bedding and clothing. Additionally he recommends that physicians and attendants change their clothing when leaving the hospital.

This may be worth trying here. Now that we must quarantine passengers aboard their ships, Dr. Douglas has given orders that the passengers be removed to the island temporarily, and that the holds be thoroughly washed and aired before their return. Stern and bow ports are opened, allowing a stream of air to pass through the hold and flush out the miasma. On many of the more recently arrived ships, however, passengers are no longer required by the captains to discard all their bedding before inspection; word has spread that the ships will be detained here regardless, and no one wants to cause extra suffering. So the passengers return to the clean holds with their filthy clothes and blankets and belongings. Wood’s Practice of Medicine notes that the disease “appears even to be capable of being conveyed in clothing, to which the poison has been said to adhere for the space of three months…It is thought that the poison can act but a few feet from the point of emanation; and attendants upon the sick often escape, if great care is taken to ventilate the apartment, and observe perfect cleanliness.” Interesting advice, if true. But what use is it? Not one thing on this island is clean. Throughout the sheds and tents, as well as the hospital, we have an infestation of lice. This in itself seems like reason to divest the passengers of their rags and provide them with new.

Nora appears to be making a full recovery. Tonight she asked me again about her brothers and this time I told her the truth: that when last seen they appeared well, but they were carried off on a steamer bound for Quebec and Montreal on May 24 and may now be anywhere. Her face turned very pale. She went outside for a while, and when she returned she asked that she be allowed to work here as an attendant. As she cannot catch the fever again, I agreed. We are desperately short-handed.

Three of my fellow physicians have fallen sick; also two Catholic priests and the same Anglican clergymen who chided me early on. At least six of the attendants are also sick.

The remainder so fear contagion that we have caught them standing outside the tents or in the open doorways of the sheds, hurling the patients’ bread rations at their beds rather than approach them. Gray bread flying through gray air.

June 27, 1847. Unbearably hot. Seven out of fourteen physicians are now ill. Of the six Anglican clergymen recently arrived, four are sick: Forrest, Anderson, Morris, Lonsdell. Our death-register now shows deceased 487 persons whose names we cannot ascertain. 116 ships so far. The backs of my hands are completely covered with hives.

Last night I stole a brief hour of conversation with Dr. John Jameson. Over a glass of brandy, and without meaning to, I complained that Dr. Jaques never talks to me if he can avoid it. John, who continues good-humored despite the lack of sleep and the working conditions, said, “You must not take this so hard. This island is a government installation, under military supervision—of course everyone’s concerned with discipline, the chain of command, the appearance of propriety. Dr. Jaques perhaps a bit more than the others. This is a political situation, at least as much as it’s a medical emergency.”

Of course it’s politics, as he said; Arthur Adam has maintained all along that the famine in Ireland is political, not agricultural, and so by extension our situation here has at least as much to do with government policy as with fever. I have not, apparently, been behaving in a sufficiently ‘military’ manner. And it’s true that John gives an appearance of going along, not asking questions or making comments when one of the superintendents tells him to do something. He smiles and nods. Then as soon as they’re gone, he does what needs doing, the way he sees fit to do it.

Am I such a troublemaker?

John said, “In the staff meetings, you ask quite a few questions. Sometimes you want to know why you can’t be reassigned here or there, why you can’t try this or that, why they can’t get better food for the patients, why the servants don’t behave better—this isn’t a situation where questions are welcomed. And then this place”—he waved his hand around my makeshift office and sleeping quarters, touching two of the walls as he did so—“What do you think it looks like, you unwilling to sleep at Mrs. Caldwell’s with the rest of us? You hardly talk at dinner, you bolt your food and run back here…some of the staff say you think you’re better than the rest of us.”

Me—who worries all the time that I’m not holding up my end. Then he brought up Nora and her work with the patients. I have given her too much responsibility, he says. I talk with her too freely.