Sugar beet wagons, circa 1908.

Young John Steinbeck broke out of Salinas whenever he could. Roaming the land awakened his senses as the town of Salinas most certainly did not. Sometimes his tomboy younger sister, Mary, was his companion on long rambles into the hills; sometimes he explored with friends; sometimes he went alone. He swam in the Salinas River; hunted rabbits; rode ponies to the ranch owned by Max Wagner’s uncle; took the little Spreckels train to Alisal Canyon, where wild azaleas bloomed; and visited Aunt Mollie’s farm in Corral de Tierra or his grandparents’ ranch near King City. The result of excursions away from Salinas was twofold: leaving him with an abiding love for the land and nurturing an equally compelling empathy for those who worked on that land.

Red Pony Ranch.

In California, migrant laborers work the land, once harvesting sugar beets, now picking strawberries and lettuce. The valley’s agricultural history is a complex mix of growers, shippers, and workers, each with a notion of how the land should be used, how migrants should be housed, and what crops should go to market when. To be the world’s “salad bowl” is a demanding venture, one Steinbeck wrote about with a clear preference for those on the margins of profit.

The Salinas Valley is a fairly narrow 100-mile swath of rich land between the Santa Lucia Range and the Gabilan Mountains, running roughly from Paso Robles in the south to Castroville in the north. This region was settled, in succession, by peaceful Indians, hopeful Spanish padres building missions, bold Mexican ranchers claiming vast land grants, and energetic American ranchers and farmers, who grabbed land as eagerly as the Spaniards and Mexicans had before them.

The road to Red Pony Ranch.

Working beet fields, circa 1908.

In the moderate climate and black soil of the Salinas Valley, many found the full measure of California’s promise. Because the northern end of the valley cuts through the coastal mountains and opens onto the sea, high summer fog, generated by cool ocean air meeting the sunny inland heat, streams into the valley around Salinas. This misty blanket protects crops from the desiccating power of the direct sun. In the winter, the temperature gradient reverses and the warmer coastal fog buffers the inland fields from wintry frost.

Until World War I, grains and sugar beets were the dominant crops. Beginning in the 1920s, acres were planted with lettuce, strawberries, celery, and broccoli—and some sweet peas (as in Steinbeck’s 1934 story “The Harness”). Salinas soon named itself the “Salad Bowl of the World,” an epithet that boldly suggests the region’s agricultural wealth and assertiveness. Nearly a century later, the Salinas Valley remains the nation’s top producer of lettuce and yields large crops of strawberries, mushrooms, cauliflower, and wine grapes as well.

Prior to 1848, native grasses covered the hills around the Salinas Valley: Oregon hair grass, Idaho fescue, and California oat grass—all bunchgrasses—grew two to three feet in height. Even before Spanish mission settlement in the 1770s, native grasses were being replaced by wild oat, brought in on ships by early Spanish explorers.

One story has it that the padres brought wild mustard seed to California to mark the mission trail. By the mid-nineteenth century, mustard carpeted the valley in the spring. “When my grandfather came into the valley,” Steinbeck writes in East of Eden, “the mustard was so tall that a man on horseback showed only his head above the yellow flowers.”

In fields and orchards, mustard roots helped break up the soil. By the 1870s, up to 400,000 pounds of mustard seed was harvested by Chinese workers each fall. Mr. Steinbeck brought mustard seed when he visited John at Tahoe in 1927, and the two made mustard in John’s tiny cabin.

For early travelers, the Salinas Valley could be forbidding, a place of sloughs, cut through by an often-dry riverbed, whipped by wind. In 1872, one traveler, Stephen Powers, found it

an execrable place at best. Everyday for seven months there rises, about ten o’clock, a wind which blows at a furious rate till nearly midnight. The dry bed of the river yields so much sand that it constitutes what is called “dry fog.” The live oaks… look like old men leaning on their hands, with their coat-tails blown over their heads. Such a blast I had to face for fifty miles.

The history of California field-workers is a rich and varied one, reflecting repeated attempts by landowners to encourage—and then contain and curtail—the influx of immigrant labor. Although men like George and Lennie often toiled in the fields, the vast majority of workers in the Salinas Valley’s rapidly growing agribusiness were immigrants brought in to help plant and build California.

After California attained statehood, Chinese immigrants came to California to work in the goldfields and to build railroads. In East of Eden, Lee tells Adam something about the sad history of Chinese workers:

The herds of men went like animals into the black hold of a ship, there to stay until they reached San Francisco six weeks later… my people have learned through the ages to live close together, to keep clean and fed under intolerable conditions…. These human cattle were imported for one thing only—to work. When the work was done, those who were not dead were to be shipped back.

Beginning in the late 1860s, Salinas landowners contracted Chinese workers to harvest wheat, the dominant crop; in the 1870s, Chinese workers cleared sloughs surrounding the new town, reclaiming land for agriculture. Well into the twentieth century, Chinese crews dug drainage ditches and slogged through waist-deep water to clear brush and trees. Their adaptability and resilience made them essential to Salinas Valley agriculture—but, throughout California, waves of anti-Chinese sentiment resulted in the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, in force until 1943, which restricted immigration to merchants, scholars, and students.

Although Chinese field-workers remained dominant until the late nineteenth century, Japanese workers gradually filled gaps created by the Chinese Exclusion Act. Until about 1910, Japanese workers thinned, topped, and harvested sugar beets in the Salinas fields. But hostility toward “Asiatics” ran high in California. A 1908 agreement between Japan and the United States curtailed immigration, and the Immigration Act of 1924 cut it off entirely.

Single Filipino men, or “stoups,” filled the gap left by limiting Japanese immigration. A story Steinbeck wrote at Stanford, “Fingers of Cloud,” is set in a Filipino work camp, where “the howling wind came through the cracks” in the bunkhouse and the pockmarked men had only “a few boxes to sit on.” Mexican laborers started crossing the border early in the twentieth century to work the California fields. Greater numbers came during the Mexican Revolution and after, particularly from 1917 to 1920, when Congress waived immigration requirements for agricultural workers.

During World War II, another wave of Mexican laborers filled the gap left when the Southwest migrants Steinbeck wrote about found jobs in the defense industry or fought overseas. Numbers of Mexican workers increased during the postwar period with the implementation of the Bracero Program, in force from 1942 to 1964, which brought workers temporarily into the United States.

Harvesting broccoli rabe.

If F. Scott Fitzgerald is the American novelist who best captures our fascination with money, John Steinbeck is our troubadour of work, the writer who best describes the value and dignity of laboring with one’s hands. Characters in Steinbeck’s fiction fiddle with Hudson Super-Six engines, dig ditches and graves, work in canneries, pump gas, and pick apples. Eliza Allen in “The Chrysanthemums” has “planting hands,” her fingers burrowing deep in the soil. Steinbeck could not have known what that meant without a love of gardening, passed on to him by his father, and without having spent hours working in the fields around Salinas, witnessing the toil of others.

In the 1930s, a decade when most California field-workers came from the American Southwest, John Steinbeck became the voice for Okie despair. Although his fictional workers in Of Mice and Men, In Dubious Battle, and The Grapes of Wrath are largely white, he certainly knew of and wrote about other histories. Themes of immigrant isolation and social ostracism are threaded throughout Steinbeck’s novels and stories. He had long been aware that some people profited from the valley’s abundance while others lived “east of Eden,” exiles from paradise. The man who would tell the tales of the world’s dispossessed developed his commitment to those on the edges when he was very young.

Beyond Salinas, the young John Steinbeck expanded his sensibilities. In the fields and valleys he discovered stories that intrigued him far more than those of wealthy growers and shippers in Salinas. The plight of Indians in the missions, the dignity of old paisanos, the toil of migrant workers, the isolation and loneliness of people living on little ranches and farms, these were the tales he would tell.

“The surges of the new restless, needy, and strong—grudgingly brought in for the purposes of hard labor and cheap wages—were resisted, resented, and accepted only when a new and different wave came in. On the West Coast the Chinese ceased to be enemies only when the Japanese arrived, and they in the face of the invasion of Hindus, Filipinos, and Mexicans.”

Steinbeck loved  Fremont Peak, a view of it caught from attic windows of his Salinas home. “The peak used to be the habitation of the shadow for me,” he wrote a friend in the 1920s. “When I had some fancy too light, and too delicate to trust to the guffaws of my own townsmen I put them up on that smooth peak.

Fremont Peak, a view of it caught from attic windows of his Salinas home. “The peak used to be the habitation of the shadow for me,” he wrote a friend in the 1920s. “When I had some fancy too light, and too delicate to trust to the guffaws of my own townsmen I put them up on that smooth peak.

And all the helpless desires and thrusting hopes which rose in all parts of me were on the peak.”

Fremont Peak (elevation 3,169 feet) remained in sight when Steinbeck rode his pony, Jill, north of town to his friend Max’s ranch, his trail roughly paralleling San Juan Grade Road. (Roads out of Salinas were named for destinations: Castroville Road, San Juan Grade Road, Monterey Highway.)

Fremont Peak.

Old Stage Road.

He undoubtedly rode by a little one-room school like the one Jody attends in The Red Pony, located at the junction of San Juan Grade and Crazy Horse Canyon roads. Across from the school is a historical marker recounting Lt. Col. John Frémont’s Battle of Natividad, a skirmish Steinbeck mentions in The Red Pony. On March 6, 1846, Fremont marched up the peak that now bears his name with his band of irregulars, mostly backwoodsmen from Tennessee and Missouri, erected a log fort and raised the U.S. flag. For three days Frémont claimed for the United States what was then Mexican territory.

Nearby, Old Stage Road winds over the steep hills north to San Juan Bautista. The Steinbeck family bounced over this narrow track when they visited the Steinbeck grandparents in Hollister, and Steinbeck traveled it on his 1948 trip to gather material for East of Eden, writing to his wife, Gwyn:

[I] found the old stage road which I haven’t been over since I was about ten years old and we went to Hollister that way in the surrey. Went over it to San Juan and do you know there were hundreds of places that I remembered. Kids do retain all right. Stopped in San Juan a while and then drove back over the old San Juan Grade which in the memory of most people is the only one. They have completely forgotten that which was once called the Royal Road and it is now just a country dirt road, which is what it always was, of course.

San Juan Grade Road remains the loveliest auto route between Salinas and San Juan Bautista, and Old Stage Road, now closed to cars after three miles, is a splendid and accessible dirt track, a four-mile hilly walk past the road’s terminus.

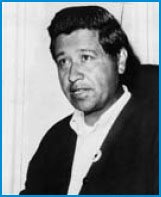

The July 4, 1969, cover of Time magazine features Cesar Chavez with a banner stating, “The Grapes of Wrath, 1969: Mexican-Americans on the March.” Like the agricultural strikes of the 1930s, the movement called la causa protested inhumane working conditions for 384,100 agricultural workers in California: inadequate housing, long hours, and low wages (and, later, indiscriminate use of pesticides). More broadly, Chavez and the United Farmworkers Union (UFW) wanted to better the lot of Mexican Americans. By 1969, Chavez’s call for a nationwide boycott of table grapes was embraced by Edward Kennedy; folksingers Peter, Paul, and Mary; and Chicago mayor Richard Daley, along with other prominent Democrats. In California, Governor Ronald Reagan called the table grape boycott “immoral” and “attempted blackmail.”

A short-handled hoe.

Largely fueled by Chavez’s crusade, in September 1972 the California Rural Legal Assistance presented a petition to the Safety Board regarding use of the short-handled hoe to weed and thin crops. Public hearings were held in March and May 1973 to determine whether the short-handled hoe was an “unsafe hand tool” that caused damage to workers’ backs. Growers argued that use of the longer hoe would cause “inefficiency.” According to court documents, “Some workers testified that the short hoe really wasn’t much faster, but that the field bosses favored them as a means of knowing at a glance if the crew was working (the assumption being that an upright person might be resting whereas a bent-over person was working).” The short-handled hoe was banned from use in the fields shortly thereafter.

Chavez led the 1960s grape boycott, working tirelessly for workers’ rights.

The summit of Fremont Peak is accessed by a well-marked road near San Juan Bautista. The view from the top is, as Steinbeck promises in Travels with Charley, panoramic.

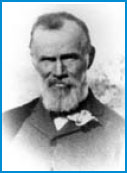

In 1896, Claus Spreckels, who had operated sugar plants in Hawaii and in nearby Watsonville, gave a rousing speech to Salinas farmers and businessmen, urging them to switch from growing wheat to growing sugar beets:

Now if you farmers will guarantee to grow the beets, I’ll guarantee to turn ‘em into sugar. I propose to build here at your door the greatest sugar factory and refinery in the world…. It will eat up 3,000 tons of beets every day and turn out every day 450 tons of refined sugar…. That means the distribution among the farmers of $12,000 every day and $5,000 more paid to workmen and for other materials in the manufacturing…. I shall buy and pay for the site and put up the factory myself.

And that he did. Acres devoted to grains became sugar beet fields. Irrigation ditches were dug. Water was pumped from the Salinas River. A few deep well pumps were sunk on company ranches; by 1924, well pumps were in general use around the valley. When  the Spreckels factory opened in April 1899, the Salinas Index compared the five-story redbrick factory to the Brooklyn Bridge and the Eiffel Tower: “the greatest of all undertakings … will stand pre-eminent as one of the wonders of modern achievement.” Claus Spreckels transformed the valley.

the Spreckels factory opened in April 1899, the Salinas Index compared the five-story redbrick factory to the Brooklyn Bridge and the Eiffel Tower: “the greatest of all undertakings … will stand pre-eminent as one of the wonders of modern achievement.” Claus Spreckels transformed the valley.

One farmer recalled, “You’d soak the ground in March or April by building borders all around the field and flooding it. Then when it got dry enough to work, you’d knock those levies down and you’d work it all real nice. Then you got your seed, beet seeds, from Spreckels. It came from Germany, most of it. Then you’d plant it and you’d cultivate it a little bit. But you’d never water it no more.”

For two decades, Spreckels Sugar Company, the largest sugar factory in the world, employed most of the valley’s agricultural workers. “Year round” employees settled in the little company town, still tidy today, community spirit still running high. Seasonal workers, “sugar tramps,” drifted in for the beet processing season, which ran for sixty to ninety days, from July through September every year. Planting, thinning, and topping the beets began earlier, and called for scores of agricultural workers, nearly six times the number needed for beans and twenty times the number needed for barley. When the factory opened in 1899, mostly Japanese toiled in the fields. But, by 1918, when John Steinbeck came to work at the Spreckels plant, Mexican field-workers had replaced Japanese field-workers. East of town, “Little Tijuana” housed these Mexican workers, only a handful of whom were allowed to work inside the factory.

The Spreckels plant closed in the mid-1980s. Although without its redbrick factory since 1992, the tidy company town, population 500, looks much as it did when Steinbeck worked at the plant.

Claus Spreckels, the West’s foremost patron of the sugar beet.

Steinbeck and his father spent long hours working for the Spreckels Sugar Company, traveling on the little narrow-gauge railroad—called the “dinky” because of the small engines—that connected Salinas to Spreckels. The Parajo Valley Narrow Gauge connected Salinas to the limestone quarries near the Alisal picnic grounds (where Cal Trask takes Abra to see the wild azaleas).

After his feed and grain store failed in 1918, the senior Steinbeck secured a job there as bookkeeper. Charles Pioda, plant manager, and his brother Mason hired Mr. Steinbeck, saving the family from certain economic ruin (the kind gesture echoed in East of Eden when Pioda helps Adam Trask). John worked as a carpenter’s assistant; later he was an assistant chief chemist and a night chemist, assessing the sugar content of beet samples from various fields to determine harvest schedules. During time off from Stanford, he was a field laborer or “straw boss,” overseeing day laborers on company ranches from Spreckels to distant Manteca in the Central Valley.

Of Mice and Men came out of his time working at Spreckels ranches. In a 1937 interview, Steinbeck said that he had “worked alongside” his model for Lennie, who didn’t kill a girl but “killed a ranch foreman” with a pitchfork.

As a young man, Steinbeck came to know just what it meant to be a “have-not” in the midst of “haves.” “Guys like us, that work on ranches, are the loneliest guys in the world,” George tells Lennie in Of Mice and Men. “They got no family. They don’t belong no place. They come to a ranch an’ work up a stake and then they go inta town and blow their stake.” Working side by side with young Steinbeck were men who made less than the thirty-two cents an hour he made as a bench chemist; who dreamed only of living “off the fatta the lan’ “; whose identity was stamped by poverty; who knew what being marginalized meant long before the word became politically correct. This perception of the sharp distinction between those who maintained power and those who never had it influenced Steinbeck greatly, and its acknowledgment became his lifelong subject.

John Steinbeck loved  Corral de Tierra. His Aunt Mollie lived on a farm there, where most farmers raised chickens or grew tomatoes to sell to Monterey canneries. “They raise good vegetables” says the bus driver to his passengers at the end of The Pastures of Heaven, “good berries and fruit earlier than any place else.” At the lower end of the valley, sandstone cliffs rise up, and to a young, impressionable Steinbeck they were King Arthur’s keep. He set one of his most puzzling stories, “The Murder,” at the base of those lofty cliffs.

Corral de Tierra. His Aunt Mollie lived on a farm there, where most farmers raised chickens or grew tomatoes to sell to Monterey canneries. “They raise good vegetables” says the bus driver to his passengers at the end of The Pastures of Heaven, “good berries and fruit earlier than any place else.” At the lower end of the valley, sandstone cliffs rise up, and to a young, impressionable Steinbeck they were King Arthur’s keep. He set one of his most puzzling stories, “The Murder,” at the base of those lofty cliffs.

In Steinbeck’s hands, Corral de Tierra becomes the Pastures of Heaven, a place both real and mythic, a valley of hazy beauty and dreams derailed. In 1939, he wrote to biographer Harry Thornton Moore:

“He saw the quail come down to eat with the chickens when he threw out the grain. For some reason his father was proud to have them come. He never allowed any shooting near the house for fear the quail might go away.” (Needlepoint by women of the Church of the Good Shepherd, Corral de Tierra)

I have usually avoided using actual places to avoid hurting feelings for although I rarely use a person or story as it is—neighbors love only too well to attribute them to someone. Thus you will find that the Pastures of Heaven does not look very much like Corral de Tierra. You’ll find no pine forest in Jolon and as for the valley in In Dubious Battle—it is a composite valley as it is a composite strike. If it has the characteristics of Pajaro nevertheless there was no strike there.

At the end of The Pastures of Heaven, a busload of tourists looks into the valley from Laureles Grade Road: “the air was as golden gauze in the last of the sun. The land below them was plotted in squares of green orchard trees and in squares of yellow grain and in squares of violet earth.”

River Road, Elisa and Henry Allen’s route in “The Chrysanthemums,” runs along the Salinas River, still a pastoral stretch of highway. The road hugs the base of the Santa Lucias, passing old barns, ranch houses, a bed-and-breakfast or two, wineries, and fields.

River Road, Elisa and Henry Allen’s route in “The Chrysanthemums,” runs along the Salinas River, still a pastoral stretch of highway. The road hugs the base of the Santa Lucias, passing old barns, ranch houses, a bed-and-breakfast or two, wineries, and fields.

The Salinas River, 155 miles long, is the third longest river in California and the largest subterranean river in the United States—until dams built in the 1950s and early 1960s kept water above ground most of the year. It flows from south to northwest, emptying into two man-made channels that carry water into Monterey Bay. For Steinbeck it was a “part-time river,” a bed that filled in the spring and dried up in the summer. As he began writing East of Eden, he thought that the Salinas River would be his principal symbol, water running above ground and beneath the surface—so much like the virtue and hidden vices of his characters. Although he abandoned the river as an organizing motif, he makes frequent references to water and the river in the novel.

The Salinas River, 155 miles long, is the third longest river in California and the largest subterranean river in the United States—until dams built in the 1950s and early 1960s kept water above ground most of the year. It flows from south to northwest, emptying into two man-made channels that carry water into Monterey Bay. For Steinbeck it was a “part-time river,” a bed that filled in the spring and dried up in the summer. As he began writing East of Eden, he thought that the Salinas River would be his principal symbol, water running above ground and beneath the surface—so much like the virtue and hidden vices of his characters. Although he abandoned the river as an organizing motif, he makes frequent references to water and the river in the novel.

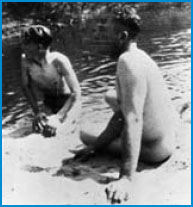

John Steinbeck and Glenn Graves by the Salinas River. “And then the summer came, and the water in the Salinas River went down until there were only pools against the bank. The Salinas River is three miles from Salinas. We could walk to it or ride bicycles to it. Mary and I rode Jill. We strung ropes to the saddle horn and the pony pulled lines of bicycles to the river. Then, of course, we went swimming.”

In March each year, the Monterey papers announce the “Season Opener,” as the county harvest begins with artichokes, strawberries, and lettuce. After a four-month hiatus, migrant workers—about 20,000 during recent seasons—return to the valley from Yuma or El Centro (where housing is cheaper) or towns in Mexico. In late March, field workers along River Road insert little lettuce plants into the ground by machine, with 6-8 workers sitting on the wings, filling rotating cones with plants, and another 3-4 performing cleanup work behind. Crews hoe the fields as the plants take root. Larger crews pick broccoli rabe, collecting stems in a little bundle, slicing the bottoms with knives hung from sheaths at their waists, tying the bunches, and tossing each bunch on a conveyor belt packing-machine that moves slowly through the fields. In October, grapes are harvested; fine wines are made along the “Monterey County wine trail.”

Mission Soledad, founded in 1791, is now reduced to a few adobe walls, but the rebuilt church provides a cool respite from the burning summer sun, and the little museum features Indian grinding stones, an original mission bell, and a nice walk through the garden. This was never a prosperous mission—summers are scorching, winters are damp, the wind is often unrelenting, and the soil is poor. Few Indians, who theoretically could help sustain the mission with their labor, lived in the region.

Mission Soledad, founded in 1791, is now reduced to a few adobe walls, but the rebuilt church provides a cool respite from the burning summer sun, and the little museum features Indian grinding stones, an original mission bell, and a nice walk through the garden. This was never a prosperous mission—summers are scorching, winters are damp, the wind is often unrelenting, and the soil is poor. Few Indians, who theoretically could help sustain the mission with their labor, lived in the region.

The remains of Mission Soledad.

The general store in Jolon today.

The San Antonio Valley. “The oaks had put on new leaves as shiny and clean as washed holly.”

Gateway to this remote, lovely, and relatively untouched valley is the nearly deserted town of  Jolon, where fifteen-year-old Steinbeck spent several weeks at a friend’s ranch. Established in 1860, Jolon once boasted eight hundred inhabitants and hosted a fiesta much like the one in To a God Unknown. It is now reduced to an adobe ruin, an abandoned hotel, and an active Episcopal church. On his trip with poodle Charley, stopping in Monterey to have a drink at Johnny Garcia’s bar, Steinbeck spoke the Since 1940, the U.S. military has held this valley. (Visitors to Fort Hunter Liggett should be sure to bring a driver’s license, vehicle registration, and proof of insurance to pass through checkpoints at the gates.)

Jolon, where fifteen-year-old Steinbeck spent several weeks at a friend’s ranch. Established in 1860, Jolon once boasted eight hundred inhabitants and hosted a fiesta much like the one in To a God Unknown. It is now reduced to an adobe ruin, an abandoned hotel, and an active Episcopal church. On his trip with poodle Charley, stopping in Monterey to have a drink at Johnny Garcia’s bar, Steinbeck spoke the Since 1940, the U.S. military has held this valley. (Visitors to Fort Hunter Liggett should be sure to bring a driver’s license, vehicle registration, and proof of insurance to pass through checkpoints at the gates.)

David Ligare was drawn to Monterey County by the writing of John Steinbeck and Robinson Jeffers. “The view from the ‘Pastures of Heaven’ where I live and work,” he writes, “is one of oak-studded hills speckled with grazing cattle, bordered by the ‘corral’ of mountains and the blue bay.” In Steinbeck’s fiction, Ligare finds a “compelling dissonance between the loveliness of this landscape and the longings and sufferings of its inhabitants.” Stories in The Pastures of Heaven and The Long Valley tell about inhabitants’ loneliness, isolation, and lack of fulfillment.

Ligare’s own Salinas Valley landscapes are less about dissonance and more about pastoral serenity. Central to his work is the notion that the gentle beauty evoked at a particular time is a fleeting moment of serenity, peace, and escape. Correct light is essential—fading daylight, approaching night, golden light, or what Virgil called the “mortal serenity of evening.” Clouds are low in the sky, as they often are in Monterey County. Grasses and flowers convey a particular time of year, as is true in Steinbeck’s work: seed heads ready to burst, lupin in bloom, oak leaves bright green.

Both Steinbeck’s and Ligare’s landscapes possess a mythic quality. Archetypes are envisioned as part of a place—like Joseph the seeker in To a God Unknown or Ma the earth mother in The Grapes of Wrath or Samuel the prophet in East of Eden.

Mount Toro figures in Steinbeck’s work, and Ligare has painted it a number of times. “It looks so large, especially in Pacific Grove, at Lovers Point, or covered with snow.” Yet in photos it is a “tiny little thing.” When Ligare paints Mt. Toro, he increases the height of it. “Fictionalizing it makes it more true.” That could be said of Steinbeck’s work as well.

Mount Toro figures in Steinbeck’s work, and Ligare has painted it a number of times. “It looks so large, especially in Pacific Grove, at Lovers Point, or covered with snow.” Yet in photos it is a “tiny little thing.” When Ligare paints Mt. Toro, he increases the height of it. “Fictionalizing it makes it more true.” That could be said of Steinbeck’s work as well.

Landscape with Mt. Toro, by David Ligare.

poco Spanish of my youth. There were Jolón Indians I remembered as shirttail chamacos. The years rolled away. We danced formally, hands locked behind us. And we sang the southern country anthem, “There wass a jung guy from Jolón—got seek from leeving halone. He wan to Keeng Ceety to gat sometheeng pretty—Puta chingada cabrón.”

Cut by streams and protected by the high coastal range, the San Antonio Valley looks much as it did when early European explorers camped near the Nacimiento and San Antonio rivers. The 1769 Spanish expedition led by Portolá was the first—traveling by land from San Diego in an attempt to find legendary Monterey Bay.

Mission San Antonio.

Two years later, the Mission San Antonio was established a few miles further into the valley. To a God Unknown is set here. In Steinbeck’s hands, this is contested land emblematic of California’s early history. A mission, an Indian village, and a white homestead each has a claim on the heart of this valley, and the book’s central thrust is concerned with land use—be it for profit, consecration, mystery, or enjoyment.

Steinbeck’s hero in To a God Unknown rides into the valley on nearly the same route used today.

Nuestra Señora, the long valley of Our Lady in central California, was green and gold and yellow and blue when Joseph came into it. The level floor was deep in wild oats and canary mustard flowers. The river San Francisquito flowed noisily in its bouldered bed through a cave made by its little narrow forest. Two flanks of the coast range held the valley of Nuestra Señora close, on one side guarding it against the sea, and on the other against the blasting winds of the great Salinas Valley.

To a God Unknown explores the untamed in man and nature: “The endless green halls and aisles and alcoves seemed to have meanings as obscure and promising as the symbols of an ancient religion.” Madrone trees “resembled meat and muscles. They thrust up muscular limbs as red as flayed flesh and twisted like bodies on the rack…. Pitiless and terrible trees, the madrones. They cried with pain when burned.” The novel resonates with the mystery of place.

Mission San Antonio, called by early padres the “mission in the wilderness,” was founded in 1771 and remains one of the most remote and untouched missions in California. It was also one of the most successful. Franciscan fathers brought in European agricultural methods, planting olive and grape vines, designing aqueducts, and turning fields for grain. Indeed, mission flour was celebrated in the region. Traces of aqueducts and fields remain. Today’s visitors can stay near the mission at the Hacienda Lodge, William Randolph Hearst’s former “hunting lodge” designed by architect Julia Morgan, or at the mission itself. Naciamento Road winds through the mountains to Big Sur and Highway 1.

Mission San Antonio, called by early padres the “mission in the wilderness,” was founded in 1771 and remains one of the most remote and untouched missions in California. It was also one of the most successful. Franciscan fathers brought in European agricultural methods, planting olive and grape vines, designing aqueducts, and turning fields for grain. Indeed, mission flour was celebrated in the region. Traces of aqueducts and fields remain. Today’s visitors can stay near the mission at the Hacienda Lodge, William Randolph Hearst’s former “hunting lodge” designed by architect Julia Morgan, or at the mission itself. Naciamento Road winds through the mountains to Big Sur and Highway 1.

South on Highway 101 is  King City, where Steinbeck’s grandparents, the Hamiltons, ran cattle on bone-dry land—the “old starvation ranch” Steinbeck called it. Although Sam Hamilton died in 1904, when John was two, John’s favorite uncle, Tom, lived on the ranch when John was a boy, and his grandmother continued to spend time there until 1912. Tom’s gentle spirit is captured in what is, in fact, his eulogy in the pages of East of Eden, including this marvelous notion: “He needed not to triumph over animals.” It was Tom who taught John to fish, Tom who left gum under young John’s pillow, guilty Tom who is Uncle John in The Grapes of Wrath. In 1912, at age fifty-two, he shot himself on a remote road near the ranch—a story also told in East of Eden.

King City, where Steinbeck’s grandparents, the Hamiltons, ran cattle on bone-dry land—the “old starvation ranch” Steinbeck called it. Although Sam Hamilton died in 1904, when John was two, John’s favorite uncle, Tom, lived on the ranch when John was a boy, and his grandmother continued to spend time there until 1912. Tom’s gentle spirit is captured in what is, in fact, his eulogy in the pages of East of Eden, including this marvelous notion: “He needed not to triumph over animals.” It was Tom who taught John to fish, Tom who left gum under young John’s pillow, guilty Tom who is Uncle John in The Grapes of Wrath. In 1912, at age fifty-two, he shot himself on a remote road near the ranch—a story also told in East of Eden.

That same year the ranch was sold to the Grab family, who still own the arid acres where Sam Hamilton in East of Eden scratches out a living. In 1948, Steinbeck wanted to buy the ranch:

I would love to have the old place to go to for a few months of the year and let the boys find out about animals and horses and grass and smells besides carbon monoxide…. I do not want to run it as a ranch. Just to go to live in the old house and to walk in the night and hear the coyotes howl and the roosters and to see the rabbits sitting along the brush line in the morning sun.

Steinbeck never did buy that ranch, never again lived in the Salinas Valley once he left home at age seventeen. But the smells and sounds and sights of his home valley never left him.

Hamilton Ranch.

Elizabeth Hamilton.

Samuel Hamilton.