Hills covered with Monterey pine and live-oak forests, owned by the Del Monte Properties Company, stand between old Monterey and picturesque Carmel-by-the-Sea. A wall might as well separate these diverse communities. Spanish Monterey, site of the military presidio and Colton Hall, place of preserved adobes and fishing wharves, is layered with two and a half centuries of California history, whereas Carmel has been burnishing its charm only since 1903. The difference is also cultural. From its inception, Carmel was a mecca for artists and bohemians. However briefly, creative individualism was Carmel’s clarion call.

Although Steinbeck maintained a wary distance from Carmel, the town affected him profoundly. Many like-minded peninsula liberals lived or worked in Carmel at some point, and Steinbeck’s career was shaped by the political radicalism and artistic ferment that was Carmel in the 1930s.

In the late nineteenth century, attempts to create a town near the white Carmel Beach and its famous mission were blocked by the area’s inaccessibility. In 1888, developers envisioned a Catholic retreat, Carmel City, similar to Pacific Grove’s Methodist enclave, but plots didn’t sell—even at twenty-five dollars—largely because the road to Carmel was a long and dusty hour from Monterey. Fifteen years later, however, two experienced visionaries, James Franklin Devendorf and Frank H. Powers (a real estate planner and a lawyer, respectively), were more successful. Carmel-by-the-Sea was marketed as an ecologically sensitive “village” designed to attract artists and writers, “Teachers and Brain Workers at Indoor Employment,” announced a 1903 brochure. “The settlement,” Devendorf wrote in 1913, “has been built on the theory that people of aesthetic (as broadly defined) taste would settle in a town of Carmel’s naturally aesthetic beauties provided all public enterprises were addressed toward preventing man and his civilized ways from unnecessarily marring the natural beauty so lavishly displayed here.” With better roads and better plans than those of Carmel City, Devendorf’s colony drew iconoclasts, creative spirits, liberals, Stanford professors, and the ecologically inclined.

For a century, Carmel’s development has been marked by a fierce commitment to rusticity, intimacy, and the natural environment, sometimes to the point of arguable extremism. Carmel has prided itself on a low-key atmosphere, rather like Taos, New Mexico, or Woodstock, New York, where the arts are cultivated amid sylvan ease. The town had no electricity until 1914 and has never had a jail or cemetery. To this day, side streets do not have sidewalks or streetlights and many houses still lack house numbers. Only recently has mail been delivered to houses—not picked up at the post office. Carmel has banned neon signs, billboards, hotdog stands, and, briefly, ice cream cones. From its inception, Carmel defined itself against unsightly mainstream culture, against, noted the local paper during Steinbeck’s years on the peninsula, “thousands of standardized towns extending from coast to coast.”

Statue of Father Serra by Jo Mora.

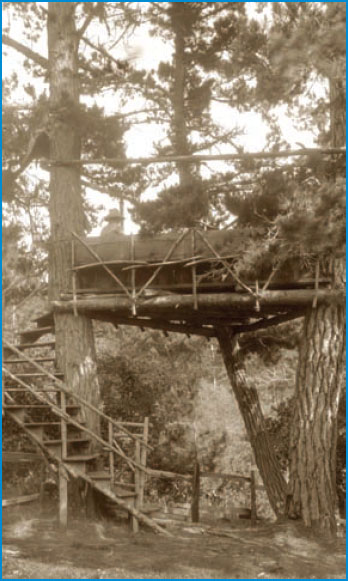

Early on, many “brain workers” were indeed drawn to this idyll—”starving writers and unwanted painters,” Steinbeck writes in Travels with Charley—and a few refugees from the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Jack London and his wife came for extended visits in 1906 and 1910, experiences that made their way into The Valley of the Moon. Writer Sinclair Lewis came in 1909 to serve as a secretary for two sisters. Upton Sinclair, muckraking novelist and, later, candidate for governor of California, moved to Carmel for a few months after his socialistic experiment, Helicon Hall in New Jersey, burned to the ground in 1907. Environmental writer Mary Austin discovered Carmel Bay in the summer of 1904 and returned in 1906 to write in her wickiup in a tree near the Pine Inn. Mecca was the Carmel house of lyric poet George Sterling, to which came satirist H. L. Mencken, novelist Theodore Dreiser, and critic and Stanford professor Van Wyck Brooks. Conversations there, reported Mary Austin, were “ambrosial.” Poet Robinson Jeffers, who arrived on the peninsula in 1914, would call those early years “The Carnival time when wine was as common as tears/The fabulous dawn….”

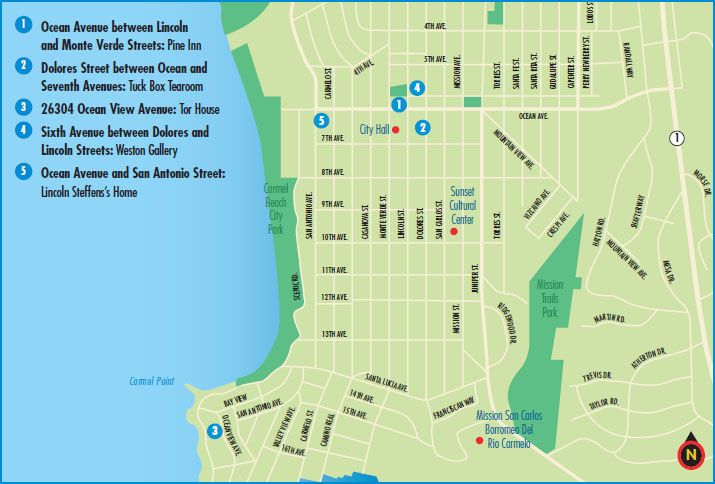

John Steinbeck fell in love with his third wife, Elaine, in 1949 when they met for dinner at  the Pine Inn, on Ocean Avenue between Lincoln and Monte Verde streets, up the street from the beach. Their connection was immediate, electric. When they finally returned to their respective rooms, neither could sleep.

the Pine Inn, on Ocean Avenue between Lincoln and Monte Verde streets, up the street from the beach. Their connection was immediate, electric. When they finally returned to their respective rooms, neither could sleep.

Mary Austin’s wikiup.

Such early denizens were serious writers, and during their months or years in Carmel they relished their camaraderie and the region’s serene beauty. Their heightened sensibilities stamped Carmel as the ultimate western bohemian retreat. Sterling, Austin, and others would regularly picnic on the beach, feast on abalone chowder, and fashion new verses of the abalone song (“Oh! Some folks boast of quail on toast, /Because they think it’s tony. /But I’m content to owe my rent/And live on abalone”).

From the earliest years, Carmel was plagued by a feeling of unreality. Self-conscious primitivism—life devoted to simplicity, health, and art—both attracted and repelled intellectuals. Critic and writer Van Wyck Brooks, for one, was uncomfortable in Carmel during his 1911 summer visit: residents were, in his eyes, artistic pretenders and idlers. Their existence ran counter to the prevailing American ideal of self-determination and energetic work habits. Brooks wrote,

Others who had come from the East to write novels in this paradise found themselves there becalmed and supine. They gave themselves over to day-dreams while their minds ran down like clocks, as if they had lost the keys to wind them up with, and they turned into beachcombers, listlessly reading books they had read ten times before and searching the rocks for abalones. For this Arcadia lay, one felt, outside the world in which thought evolves and which came to seem insubstantial in the bland sunny air.

I often felt in Carmel that I was immobilized … for there was something Theocritean, something Sicilian or Greek, in this afternoon land of olive trees, honey-bees and shepherds.

This was also Steinbeck’s view. Life was simply too easy, the setting too beautiful, the literary output not chastened by suffering, struggle, and woe.

By the 1930s, many thought that Carmel’s artistic identity was set: the place did not nourish serious work. In his 1930 survey of California writing, Carey McWilliams notes that “there are several volumes of ‘exquisite’ verse published annually in Carmel of which the least said the more charitable.” John and Carol Steinbeck agreed. She collected bad seagull poetry published in local papers. He wrote a friend in 1929 that he had seen a Carmel writer, “H. Pease, and his shopkeeper’s attitude—his wrapping up stories in butcher paper and delivering them to a hungry public—horrifies me.” To Steinbeck’s mind, literary pretenders lived in Carmel. “We have literary acquaintances in Carmel,” he wrote to a friend in 1931, “writers of paper pulp and juvenilia. They hate me, despise me because I can’t ‘sell’ anything.” He socialized with Jack Calvin, who had published a boy’s book on the salmon fishery of Alaska and had worked with Ricketts on the manuscript that became Between Pacific Tides. In another letter, Steinbeck describes a party that he and Carol attended shortly after settling on the peninsula.

We went to a party at John Calvin’s in Carmel last week. These writers of juveniles … wring the English language, to squeeze pennies out of it. They don’t even pretend that there is any dignity in craftsmanship. A conversation with them sounds like an afternoon spent with a pawnbroker. Says John Calvin, “I long ago ceased to take anything I write seriously.” I retorted, “I take everything I write seriously; unless one does take his work seriously there is very little chance of its ever being good work.” And the whole company was a little ashamed of me as though I had three legs or was an albino.

This was the face of Carmel that John and Carol emphatically and vocally rejected.

Carmel-by-the-Sea on a sunny day.

But another side to Carmel drew in the Steinbecks—and many other serious artists. Carmel fostered individualism. It was and still is artistically inclined. Although the town became more conservative in the 1930s, when real estate and business interests lobbied for control, Carmel continued to nurture a vigorous and outspoken liberal core. Local papers like the Carmel Pine Cone and the short-lived but sophisticated Carmel Cymbal give ample evidence of keen cultural awareness throughout the 1920s and 1930s. In a 1926 edition of the Cymbal, for example, poet and librarian Dora Hagemeyer reviewed Countee Cullen’s poems, discussed “The Trend of Modern Fiction,” and analyzed Bertrand Russell’s views on education. In the same year, the paper announced a series of lectures on “Five Approaches to Modern Music” and a talk on abstract painting. It reprinted Dorothy Parker’s poems from the New Yorker, Hayward Broun’s column from the New York World, and Ernest L. Blumenschein’s article on “The Taos Art Colony.” Wit marked each issue: a series on “Prominent Citizens of Carmel” featured pet dogs.

From Lake Tahoe, Steinbeck wrote his parents in dismay when hearing of owner Bassett’s financial difficulties with the Cymbal: “It is the only paper of its kind, and a really interesting sheet with legitimate pretensions of individuality and cleverness…. Bassett says what he pleases, and that is a joy no matter how you may disagree with him.” In short, Carmel of the 1920s and 1930s was a sophisticated community.

Throughout the years, many serious artists and intellectuals have gravitated to Carmel. In the 1930s, the community was remarkably varied. Joseph Campbell came through in 1932: “At last,” Campbell wrote “ … a world of my contemporaries. I don’t know why, but suddenly I felt that this was exactly what I had lacked—this being one of a world of my own age.” Ed Ricketts lived there in the early 1930s, as did Francis Whitaker, artist blacksmith and founder of the John Reed Club, and Mary Bulkley, feminist and poet, who lived on Casanova Street for twenty years. She often played music for Steinbeck when he came to her home to talk. “Miss hearing the music so much,” he wrote her from Los Gatos. “It was a good thing. I wish I could have some right now.” He inscribed a copy of Tortilla Flat to her: “To Miss Mary Bulkley: Pablo said—’Mrs. Palochico has given Danny a harmonica.’ ‘This may not be a good thing,’ Pilon observed. ‘For music brings more out of a man than was ever in him.’ JS” The man who wrote his books based on the “mathematics of music,” structured novels on Bach’s chords, and listened to Tchaikovsky must have found Mary Bulkley’s musical sensibilities soothing.

Four Carmel artists and writers in particular helped shape Steinbeck’s art—two he knew well personally, two he knew through their work: Beth Ingels, journalist; Lincoln Steffens, journalist and muckraker; Edward Weston, photographer; and Robinson Jeffers, poet. All four were bound intimately to the landscape and sensibility of the region. Their clear-eyed and vivid sense of place and culture tallied with Steinbeck’s own.

Carmel’s most beloved bungalow is the  Tuck Box Tearoom on Dolores Street between Ocean and Seventh avenues, a shop designed by Hugh W. Comstock. The story behind this and other Comstock houses in the town is as charming as the cottages themselves.

Tuck Box Tearoom on Dolores Street between Ocean and Seventh avenues, a shop designed by Hugh W. Comstock. The story behind this and other Comstock houses in the town is as charming as the cottages themselves.

In the 1920s, Carmel resident Mayotta Brown made popular felt and rag dolls, “Otsy Totsys.” When she married Hugh W. Comstock, a Midwestern farmer’s son with no training in architecture, he built in their backyard (on Torres near Sixth Avenue) a doll house showroom that he called “Gretel” for the Otsy Totsys. The next year he built “Hansel.” Demand ran high for “fairy tale houses,” as the Comstock cottages were first called. They were constructed of chalk rock, bent pitched roofs, and whimsical leaded glass windows. He built with native materials—rock from the Carmel Valley, hand-carved timbers, hand-cut redwood shingles, and hand-forged fixtures. Built between 1924 and 1930, the little houses were originally painted grey with olive trim.

The Tuck Box Tearoom.

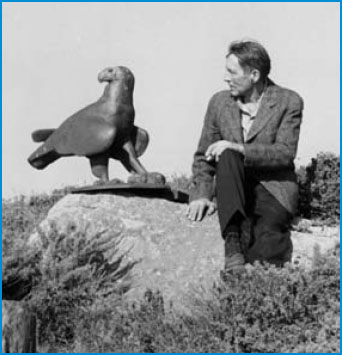

Robinson Jeffers wrote “the most powerful, the most challenging poetry in this generation,” declared the New York Herald Tribune in 1928. Four years later, he was on the cover of Time magazine. That same year, Edward Ricketts, John and Carol Steinbeck, and Joseph Campbell pored over Jeffers’s poetry. According to Campbell, Carol came into the lab one day exclaiming, “Really, I’ve got the message of ‘Roan Stallion’—and she recited parts.”

… Humanity is the start of the race; I say

Humanity is the mold to break away from, the crust to break

through, the coal to break into fire,

The atom to be split.

Tragedy that breaks man’s face and a white

fire flies out of it; vision that fools him

Out of his limits, desire that fools him out of his limits…

For Ricketts, the Steinbecks, and Campbell, a poet who talked about breaking cultural and humanitarian boundaries was a revolutionary voice, a kindred soul. This poet of “inhumanism” wrote about a world that was not man-centered. In his verse, Jeffers cultivated what he called a “reasonable detachment” that allowed for “transhuman magnificence.” His ideas certainly made their way into the book Steinbeck was writing at the time, To a God Unknown. “The whole book was an attempt to get away from the particular form of fantasy which goes by the name of realism,” Steinbeck wrote a friend in 1933. Campbell reported that he read and reread lines from “The Roan Stallion” on his 1932 collecting trip with Ricketts. And Ricketts used Jeffers’s poem to articulate his notions of transcendence: “modern soul movements,” he wrote, see “not dirt for dirt’s sake, or grief merely for the sake of grief, but dirt and grief wholly accepted if necessary as struggle vehicles of an emergent joy—achieving things which are not transient by means of things which are.”

Jeffers’s “inhumanism” is closely aligned with what Steinbeck was getting at in his own fictional stance—to see humans as part of a larger whole. In 1936, Jeffers said in an interview: “People have always taken themselves too seriously. They don’t realize what a tremendous lot there is outside themselves. After all, man is just an animal which has developed.”

Robinson Jeffers near Tor House, looking at a hawk statue.

Oddly enough, for all their appreciation, neither John nor Carol Steinbeck met Jeffers during their peninsula years. In 1938, when they were living in Los Gatos, the Steinbecks were finally introduced to Jeffers by Bennet Cerf. Jeffers’s reclusive lifestyle reflected his fierce individualism. Sculptor Gordon Newell tells of offering to help Jeffers build  Tor House, at 26304 Ocean View Avenue, on the Carmel coast. Jeffers refused Newell’s assistance: “He wanted to do it himself,” Newell reflected. His wife, Una, concurred: “I think he realized some kinship with [the granite] and became aware of strengths in himself unknown before.” This insularity kept him aloof from many in the town—literally up in his “hawk tower,” built in the early 1920s and modeled on Yeats’s tower in Ireland.

Tor House, at 26304 Ocean View Avenue, on the Carmel coast. Jeffers refused Newell’s assistance: “He wanted to do it himself,” Newell reflected. His wife, Una, concurred: “I think he realized some kinship with [the granite] and became aware of strengths in himself unknown before.” This insularity kept him aloof from many in the town—literally up in his “hawk tower,” built in the early 1920s and modeled on Yeats’s tower in Ireland.

Although Tor House is now surrounded by houses worth millions of dollars, it retains a feeling of isolation and independence. Jeffers’s granite presence remains in rooms furnished as he left them.

Robinson Jeffers.

Beth Ingels was Carol’s staunch buddy. She read several books nightly, and, like Carol, had a dry wit and an unconventional manner. Beth became friends with John as well, and she was a more significant influence on his prose than anyone might guess. Like John, she loved local history and stories. Beth and Carol helped turn Steinbeck’s gaze from the mythic to the regional.

In 1930, Beth penned a column for the Carmel Pine Cone, “Carmel’s Beginnings.” One piece that year concerned the “hiding place” of bandit Tiburcio Vasquez in Corral de Tierra. “Cabins still stand there that were occupied by him and his men,” she wrote—a historical note that makes its way into Steinbeck’s The Pastures of Heaven. Indeed, it was Beth who told Steinbeck the family stories of Corral de Tierra, her childhood home. She had considered writing a book about the area herself: in one of her notebooks is a list of possible tales about Corral de Tierra, her outline for a novel. Another notebook page lists stories entitled “Romance on Tortilla Flat”—including a reference to “the Pirate.” Beth’s unpublished stories and proposals are eerily close to Steinbeck’s own. She kept a dog notebook in order to write “a parody of serious dog books, with photos of dogs doing things they shouldn’t.” And she completed a manuscript titled “Cannery Row” about women cannery workers. Beth Ingels mined the local terrain in which Steinbeck would strike pay dirt.

Carol and Beth created Carmel’s first directory in 1930.

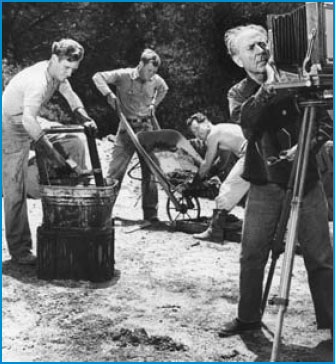

To many critics of twentieth-century literature, John Steinbeck is hardly a modernist writer. For them, he is not experimental (“make it new” is one modernist cry) but a man working consciously in a realistic mode. Others see him as a naturalist, a writer who insists that human lives are shaped by forces outside human control, or as a regionalist, a writer recording the disharmonies, traditions, and patterns of a specific place and time. But Steinbeck can also be understood as a modernist, a man of the West experimenting with unfettered language, photo-sharp realism, and an unsentimental, scientifically detached view of human lives. “The only advantage I can see about writing at all,” he wrote to a friend in 1931, “is to try to overturn precedent. All of my work has been built on plans more or less unused…. Personally I think publishers never give the reader credit for enough intelligence.” Steinbeck shared with other modernists a distrust of realism. If his prose is often journalistic in its precision, it is also suggestive, layered. Perhaps the vision of Edward Weston, modernist photographer, was closest to Steinbeck’s own.

Certainly Weston was an acquaintance of Steinbeck’s; in the late 1930s, Weston’s assistant took one of the only formal photographs Steinbeck permitted during the decade. And Steinbeck would have known Weston’s photographs, mostly landscapes with a close eye for natural objects. Rejecting the sentimental photography known as pictorialism, the f.64 group, which Weston helped organize in 1932, advocated sharp realism in treatment of commonplace subjects and precise rendering of detail. The f.64 photographers imposed no “qualities foreign to the actual quality of the subject” in order to capture “the life force within the form.” Their photographs were a visual rendering of Steinbeck’s nonteleological acceptance of what “is.” Equally committed to natural expression, Steinbeck spent the early 1930s mastering the taut sentence, stripping his prose of archaic and Latinate words, ornate phrases, and heavy symbolism. Weston’s art, like Steinbeck’s until 1935, was staunchly apolitical, focusing instead on the California landscape. For Weston, beauty was itself an end.

Weston and Steinbeck suffered at the hands of the East Coast establishment that hardly recognized the modernity of works that seemed to self-proclaimed avant-garde critics mere vestiges of realism, harking more to a rural past than to a complex future.  The Weston Gallery is on Sixth Avenue between Dolores and Lincoln. It carries the work of Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, and other photographers.

The Weston Gallery is on Sixth Avenue between Dolores and Lincoln. It carries the work of Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, and other photographers.

Edward Weston at the camera, with sons (l-r) Cole, Neill, and Chan building Weston’s adobe house on Wildcat Hill, Carmel Highlands, 1948.

“In the 1930s if you weren’t a radical, you were a hunk of protoplasm.”—Caroline Decker, labor organizer

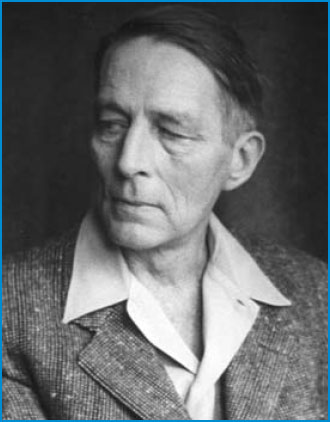

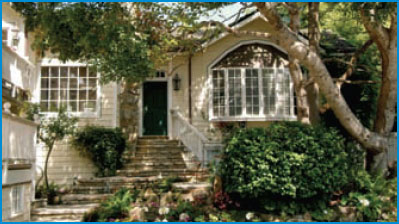

Not all who came to  Lincoln Steffens’s home at Ocean Avenue and San Antonio Street between 1927 and 1936 agreed with the politics of the ailing muckraker: “they came because there was greatness, kindliness, wit, knowledge, rich experience and sympathy in Lincoln Steffens,” reported the Monterey Peninsula Herald when he died on October 8, 1936. They came because Steffens, like Arthur Miller decades later, stood for something essential to the liberal tradition: the free exchange of ideas, sympathy for the underdog, and scorn for rigid ideologies. “A lot of social things were happening,” observed 1930s activist Richard Criley, “currents that centered on Steffens’s household.” His Carmel home was a beacon for young journalism students from Stanford, radical politicians, actors, artists, scholars, and writers.

Lincoln Steffens’s home at Ocean Avenue and San Antonio Street between 1927 and 1936 agreed with the politics of the ailing muckraker: “they came because there was greatness, kindliness, wit, knowledge, rich experience and sympathy in Lincoln Steffens,” reported the Monterey Peninsula Herald when he died on October 8, 1936. They came because Steffens, like Arthur Miller decades later, stood for something essential to the liberal tradition: the free exchange of ideas, sympathy for the underdog, and scorn for rigid ideologies. “A lot of social things were happening,” observed 1930s activist Richard Criley, “currents that centered on Steffens’s household.” His Carmel home was a beacon for young journalism students from Stanford, radical politicians, actors, artists, scholars, and writers.

In 1931, Steffens had published Autobiography, and his fame grew with its wide reception: there was a long waiting list for the book at the Carmel library. He became Carmel’s liberal conscience, a public defender of communism, the presence behind—if not a member of—the local John Reed Club, a few liberal spirits who would gather to discuss socialism and communism. “I am not a Communist,” he explained to a Harvard undergraduate. “I merely think that the next order of society will be socialist and that the Communists will bring it in and lead it.” From 1932 on, California liberals became more deeply involved with labor situations, largely because of the widely publicized 1933 cotton strike, the 1934 waterfront strike, and the 1936 Salinas lettuce strike. Steffens and his spirited wife, Ella Winter, hosted radicals and communists at their home, donated to striking workers, and sheltered fugitive organizers. Steinbeck’s political radicalism took root in Steffens’s home.

Lincoln Steffens.

Initially reluctant to take sides in the labor dispute, Steinbeck attended a few meetings of the John Reed Club—just watching—and was then urged by Carol, Steffens, and Winter to interview strike organizers hiding out in Seaside, a few miles up the coast. Steinbeck began with the idea of writing a biography of an organizer; he ended up writing In Dubious Battle, a novel, wrote Steffens, that was a “stunning, straight, correct narrative about things as they happen.” Without Steffens and Winter, Steinbeck may never have written his labor trilogy of the late 1930s: In Dubious Battle, Of Mice and Men, and The Grapes of Wrath. Steffens, wrote Martin Flavin Jr., “made people believe not in ideas but in themselves, and that is why they came to him.”

Lincoln Steffens’s home, Ocean Avenue and San Antonio Street.