CHAPTER ONE

IMAGINING A BOY

What Were You Thinking?

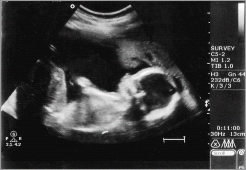

ANDREW’S PARENTS ARE GRAPPLING WITH THE ISSUES THAT OCCUPY THE mind of every loving parent. They aren’t sure how to strike a healthy balance in their son’s life between sports and academics, music and video games, friends and family time. Should they let him watch TV before he cleans up his room? When should they stand firm and when should they let their son decide for himself? They agree it’s too early to think about college. But while they don’t want to pressure him about eventual career choices, the family business does have his name on it. “We’ll just take a wait-and-see approach,” his mother says gamely as she pats her very pregnant belly. It is two weeks before Andrew’s due date. As for Andrew, he mostly busies himself making wide turns in utero, the bulge of his tiny foot tracing an impressive arc across his mother’s midriff.

Perhaps you, too, are expecting a boy. And if he is your first child or the first boy in your growing family, your curiosity and concerns about a boy’s life fill your thoughts and conversations. You have heard other mothers say, “They really are different!” And, of course, they are. If they weren’t, there would be no point at all in my writing this book. “Boys are easier than girls,” you hear. “Boys are an open book.” “Boys love their mothers.” But then what do you make of all those stories about boys being uncommunicative, behaving badly or struggling through school, stifling their inner life or losing themselves on the way to becoming men?

If this is your first foray into the intimate life of boys, you may be excited or nervous at the prospect. If you already have a son, or you had brothers, or you are a dad and remember your own boyhood, then your outlook on parenting a boy may have you feeling all the more confident and encouraged—or wary, bracing for the worst.

Perhaps you are the mother of a five-year-old boy and you are feeling a bit edgy about his interests. “My son really likes to play with guns,” one mother told me. “I don’t like them and I won’t allow them in the house, so one day at breakfast he made a gun with his finger and his thumb and he ‘shot’ his brother with it! Why does he keep doing that?”

If you are that mother, you may be worried that, despite your great love for your son and the good home in which he is being raised, his interest in guns is a sign that he’s going to grow up to be violent and dangerous. That’s an uncomfortable feeling.

Perhaps you are the mother of a two-year-old and your little boy is suddenly beginning to seem different to you. He is starting to disobey you, to look right at you when he breaks a rule or touches something he’s not supposed to touch. He laughs gleefully when you scold him. He seems so willful and defiant. Is that normal?

Or perhaps you are the mother of an older boy who has begun to pull away from you into a boys-only world that is clearly off-limits to moms. The goodnight chats are getting shorter and details of his day less forthcoming. You’ve heard that happens with boys, but you and your son have been so close—surely not him, not yet!

If you are a dad, perhaps you are not too proud to admit that you are a bit nervous about raising a boy, even though you were a boy yourself and you should, theoretically, know all about it. Maybe you had a hard time as a boy or have mixed feelings about your father, and you want it to be different for your son. Or perhaps you were a lucky boy and a lucky man, an enthusiastic dad who wants to get it right for your son. If you are a dad or father-to-be and you are making this effort to deepen your understanding about the life of boys, then your son is already a lucky boy, too.

IN THE BEGINNING: WHAT MAKES A BOY A BOY

Though it may be surprising, genetically the female form is the “default setting” for human beings. That is part of the reason that boys have a more difficult journey toward birth and have more health complications at birth than girls do. The tendency toward the female form in humans is very strong.

The start is predictable enough. The sex of your child is decided at the moment of conception, when the sperm penetrates the egg. The mother’s egg always contributes the X chromosome to the union; the father can transmit either the X or the Y chromosome, depending on which sperm completes the journey. If the egg receives an X from the father, the child will be a girl: XX. If it receives a Y chromosome, the child will have the genetic makeup for a boy: XY. Girls are better protected from certain genetic illnesses by having the XX combination. Even though an embryo may have the male XY chromosomal combination, an extra hormonal step is required to transform a fetus into a boy. If, for any reason, that extra step does not occur, the child will look like a girl, whether it is genetically XX or XY. For the first six weeks of life, then, an embryo looks the same whether it is going to be a boy or a girl.

If the Y chromosome is present, there is a gene on the short arm of the Y called the sex-determining region, which begins to transform the embryonic gonads into fetal testes. Very soon thereafter, the testes begin to produce a protein-like substance that blocks the development of the uterus and the fallopian tubes. The testes also secrete testosterone, the male hormone, and so development of a boy begins.

Not only must the male hormones be present to produce a boy, the fetal organs must respond to it. If they do, the tissue that might have formed the genitals of a girl, the labia, fuse together and become the scrotum of a boy. If you look at the scrotum itself, you can see that it looks as if it has a seam down the middle, as if it were sewn together out of two parts. That is because it could have been separate halves, in a female.

The tendency toward female development is very strong, and if anything goes wrong in the process of producing a male, it may result in miscarriage. We know that more male fetuses are spontaneously aborted during pregnancy and more boys have congenital defects or early respiratory problems at birth. Boys are more biologically vulnerable than girls from the beginning of life until the end of life.

BEYOND BURPING, BUMPERS, AND BABY GATES

Once you accept the miracle of a child coming into your life, once you embrace the humbling journey that parenting is for all of us, the question that drives nearly every conversation about boys, whether you are expecting your first or you have a houseful of them, is: What makes boys tick?

Development is the fundamental engine of a child’s growth, the ongoing process in which nature, nurture, and sheer luck come together and a unique human being emerges. The biological story of growth and advice about prenatal health and the day-to-day care and feeding of infants and children are well covered in general parenting literature and medical checkups. We’re here to focus on the psychological development of boys, the inside story of how a boy’s inner life takes shape and progresses through infancy, childhood, and adolescence. It’s a process that isn’t always easy to see or understand, not because boys intentionally hide it (though they attempt to do so at times) but because they show it in ways that adults don’t always recognize. But it’s all there. In everyday life with boys they are always onstage, showing us what’s new. Against that developmental backdrop, in the chapters ahead we’ll examine the key issues of psychological development that dominate each stage because that is, for you and your son, where the greatest challenges and drama of childhood—and parenting—play out.

If pregnancy and parenthood have left you much time to think, you are full of expectations and wonderings about your boy. You are imagining your son as he will be in six months or two years or twenty years. You may be reading a lot of parenting literature and hearing advice from family, friends, and total strangers. And every day in the news there is another research finding about child or adolescent brain science and gender differences, but very little on their actual relevance to raising your son. How do you turn all that into intelligent, intuitive parenting for raising a boy? How do you begin to answer the two most important questions for the next eighteen years: What do boys need? What is my son going to need from me?

Those are questions we’ll address in the pages ahead, but before we do that, let’s look back to the time when your thoughts about boys first took shape long ago.

YOU HAVE BEEN IMAGINING A BOY FOR A LONG TIME

You may feel newly called to this deep exploration of the inner life of boys, but I want to suggest the surprising idea that you have been thinking about what makes boys tick all of your life, or almost all of it. Thinking about having a baby someday—and imagining that baby as a boy or a girl—is one of the most basic of all human thoughts. It starts early in life. As soon as they can talk and engage in imaginary play, children—boys as well as girls—begin to enact the role of parent, first by themselves and then alongside other children, imitating the actions of the mothers and fathers they love and watch intently every day.

Most of us don’t remember what we played when we were three or four years old. That is why I want to remind you that you almost certainly did engage in some version of this domestic role-playing game, taking the role of a mom or dad, rocking a baby doll (or, if you were a boy, perhaps dismantling it or making it fly like a superhero or roll in the mud), and holding forth on what boys like and girls prefer. You “played doctor,” asking bold, uncensored questions about body parts, making mental notes. You continued as a child to school yourself in a child’s everyday version of gender studies, offering your expertise to any parent, teacher, or other child whom you felt was short on insight. From the age of five, when her younger brother arrived, my daughter, Joanna, objected to anything we did for our son, Will, that didn’t seem properly masculine to her. “Mom, that’s not for boys,” she would declare about a toy or an outfit that was too androgynous to pass her gender test. She was afraid that we wouldn’t raise our son in the right way.

In school, if you were a girl, you may remember complaining to a teacher about a bothersome boy—the noisy, pesky, clumsy, or fidgety boy, the boy who bugged you to distraction. Or you might recall disliking boys in a group, especially when they chased you and your friends on the playground or, perhaps in your teens, when you found them aggravating or baffling for different reasons.

If you were a boy, you remember how it felt to posture (or try to) around girls. You may have refused to play a game or do something someone suggested, protesting loudly, “That’s for girls!” or “We don’t want to be in reading groups with girls,” a solid declaration of what eight-year-old boys like and what they hate.

These childhood examples of how we came to know boys or imagine boys’ needs or wants may seem far removed from the adult reality of parenting a boy. They are not. Our childhood experiences form a huge reservoir of memories, thoughts, dreams, and feelings, many of them unconscious, that we bring to bear in parenting our own child. Whether we remember those moments or not, we have been coming to conclusions about boys our entire lives, and as a result, we have some pretty strong opinions—I call them imaginings—about what boys will be like, how easy or hard they are to raise, or what they might need as they grow up.

In the thirteenth century, Vincent of Beauvais, author of the Speculum Maius, the great encyclopedia of the Middle Ages, observed, “Woman is man’s confusion.” It seems to me that the obverse is also true: man—and thus boy—is woman’s confusion. So, along with the general activity and demands of parenting a boy, mothers face that formidable gender gap and the unique, ongoing challenges and sweet rewards that come with it. And what about fathers, with the home advantage of gender affinity? Any honest father will admit that gender familiarity breeds its own kind of challenges and rewards—and sometimes no less confusion.

CIRCUMCISION: TO DO OR NOT TO DO?

THAT IS THE QUESTION

There isn’t much about planning for your newborn son’s arrival that is as private a matter and yet as publicly debated as circumcision, the surgical removal of the foreskin surrounding the head of a boy’s penis.

It is a quick procedure that leaves an infant boy bleeding, breathless, crying, and, some people believe, terrified and overwhelmed. Others consider it a quick procedure from which an infant quickly recovers, both physically and psychologically. As for any traumatic effect, one mother told me: “Hey, being pushed through the birth canal is pretty traumatic, too.”

Circumcision generally is performed shortly after delivery, or sometime within the next few days. In Judaism, circumcision is a religious requirement performed on the eighth day by a specially trained rabbi in a ceremony called a bris. Circumcision also is a religious custom among Muslims.

The results of a circumcision are, obviously, lifelong. Most boys in the United States are circumcised; most boys in the rest of the world are not. The puzzling discrepancy can’t be resolved here, but it does mean that whatever you choose, there will be millions of boys and men who share your son’s “look.”

The medical pros and cons are something to discuss with your pediatrician and your spouse. Research suggests health benefits from circumcision, including significantly lowered risk among men for contracting HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, through heterosexual sex; a lower risk of other sexually transmitted diseases; and a lower risk of cervical cancer among women whose male partners are circumcised. That said, I don’t think that medicine can provide us with a definitive answer on whether or not to circumcise boys. Let’s be honest: circumcision is a cultural custom based on religious grounds, aesthetics, father-son similarity, and tradition. Either these things matter to you or they do not, and you decide accordingly.

Some people feel that circumcision gives the penis a more aesthetic look: cleaner, smoother, with a head like a rocket. Some women say they prefer it to the more complicated look of the uncircumcised penis. Many therapists and medical doctors suggest the father-son factor is meaningful. Parenting advisor T. Berry Brazelton, M.D., concludes that the father should have the last say in the matter. Most mothers, armed with information from the Internet and family tradition, have their own opinions on the subject.

What do men think? Fathers shared these thoughts:

I am circumcised, and I have to say that it has never presented itself as a good thing or a bad thing—it’s really a non-issue. My three sons are not circumcised, and we chose not to based on things we read as far as the procedure versus the need. The cleaning, if done right, is a pain…but it has not seemed to be an issue—no infections that we know of! It was a simple decision for us, as in the end the real question was “Do we really want our hours-old child to have part of his penis cut off?”

We agonized over the decision, endlessly. I am pleased we did it. When our son was growing up he would sometimes come into the bathroom and check out “correct form” when I was peeing. He sometimes liked to go simultaneously. I allowed this because I sensed that this was a becoming-a-person moment. I think it helped bonding that his equipment looked like my equipment. Also some of our friends who chose not to circumcise have had some negative health outcomes.

It was a simple decision. My wife and I both felt the boys would be more comfortable if they looked like their dad. We were a little more surprised at the open discussion of our decision. When she was pregnant with our first son, my wife was teaching at a Catholic women’s college. I think she was a bit taken aback when the nuns there engaged her in discussions about our son’s circumcision. Speaking only for myself, I think this simple medical procedure has become unnecessarily politicized in the United States.

We did not circumcise our first son because there seemed to be no reason, but we did just circumcise our second son because of a study that was mentioned in Time magazine about AIDS rates related to the toughness and openness of the glans. Either time, though, it was not a difficult decision for me. My wife found it difficult to have our second son circumcised because of the pain she perceived him experiencing.

For whatever reason, if you choose circumcision, you have the precedent of thousands of years of human beings who have decorated and cut their bodies for a variety of cultural or religious reasons. Just remember that when your son is seventeen and wants a tattoo, you’ll have little credibility to say, “Son, I wouldn’t want you to do anything permanent to your body.”

As for the idea that circumcision is inherently traumatic and leaves huge psychological scars, I’m not convinced. In my experience as a therapist I’ve never had a man in my office complain about being circumcised or uncircumcised. One way or the other, boys and men seem to end up pretty satisfied with their penises.

The sex of your child, then, is going to pull all of this out of you: your history as a male or female, your experience, your likes and dislikes. It will draw on your deepest feelings about your father, your brother, and, if you are a mother, everything that has ever gone on with your husband. The fact that your child is a boy is going to shape your life and change your psychology forever—and not just the way you feel about boys. Brain research shows that raising children shapes the way you think—neurologically—about them, too. Hormones and mirror neurons develop a sensitive biochemical circuitry that creates new connections and pathways in response to experience. We don’t just experience parenthood; parenthood shapes all of our experiences. With this brain-mind-body linkage in place, and imaginings already in progress, it doesn’t take much to push the “boy button” in your psyche and set all your personal preformed “boy” psychology into motion.

IS IT A BOY OR A GIRL?

Once you’ve got a baby on the way, the simplest question in the world—Is it a boy or a girl?—is fraught with implications. The question can set off a flood of feelings about boys that may include some positive ones, a number that are unhappy, and some that are ambivalent. A woman whose father had died when she was young told me she felt “both pride and intense anxiety” when she found out she was having a boy:

I was raised, essentially, entirely by women in a family of women…. Men and boys always fascinated me, and I’ve always loved them, been fond of them—but they always seemed exotic, hairy, wild, noisy, unpredictable, with their big voices and big stories. Great fun, absolutely delightful—couldn’t do without them. But also a little scary. The thought that I had to parent one of these was very intimidating.

Another mom described the chorus of concerns the news triggered for her:

Panic mode! I had some anxiety about raising a male child myself. I am married to a wonderful man who is a terrific father, and it was not his capabilities I questioned, it was my own. “Old tape” is hard to stop replaying.

Each of us has “old tape” when it comes to boys, and parenting a boy—even just thinking about becoming the parent of a boy—pushes the play button. This mother felt she was “particularly sensitive to gender preference,” but parents who say they have no strong preference about gender are nonetheless full of feeling about it, full of imaginings, as these mothers share:

At first I was thrilled to learn I was having a boy, and then suddenly worried that he would have to go to war someday.

I was shocked. I thought it was a girl. A boy? A boy? What would I do with a boy?

I prayed for a son because I didn’t want to go through the terrible turmoil my mother and I had experienced, especially when I hit puberty. But I also always loved the idea of a boy. A boy seemed like a child I could roughhouse with more easily.

What if, for any of a number of reasons, the thought of having a boy was close to unimaginable for you? One mother recalled that when she found out she was carrying a boy, she felt “a little worried because boys seemed so much more boisterous than girls.” She also worried, she said, because “he would be an ‘other’ just by the very fact of him being a different sex than me. How would that be?”

Author Andrea Buchanan, in her introduction to a collection of essays by mothers of sons, wrote, “Long before I got pregnant, I began to fantasize about my imaginary daughter. I rarely imagined having a son. So a few weeks ago, when the ultrasound technician’s pointer indicated my unborn son’s rather obvious pointer, I was as shocked as I have ever been in my life.”

As shocked as I have ever been in my life—that’s saying a lot, and I think it speaks to the power of our expectations. How do you fall in love with someone, even a baby, who has so upset your expectations? How do you turn on a dime when your fantasies of the future have been so disrupted?

The mother of a young son, pregnant for a second time, cried when the prenatal test showed this child to be a boy: “I was saddened that I would never have a girl—a child in my likeness.” Another mother described her attitude adjustment: “I had my heart set on having a girl and I cried when I found out it was a boy…. But by the time he was born, I didn’t care one way or the other.”

Rose and her husband, Nate, were the happy parents of two daughters when she became pregnant for the third time. When they learned from an ultrasound that this child was a boy, Nate’s immediate reaction was to say, “We’ll need to put up curtains with baseballs on them.” His comment surprised Rose, and she later teased him because he had never mentioned curtains for either of their two daughters. Why did he think sports-oriented curtains were essential for a boy when he’d never imagined something like that for a girl? Confronting these die-hard stereotypes stirred up some of Rose’s gender-equity sensitivities.

An even more personal historical conflict awaited Nancy. Nancy was a second child born eighteen months after her older brother died at age three from meningitis. She had never known him, but she knew very well that his death had, in some sense, destroyed her parents’ well-being. “I was the replacement child,” she told me. “I was born to heal and repair a wound. It was an irreparable wound; I never should have been asked to do that.” After her older brother’s death her mother had written to another family member, “This next child is our only hope for a cure.” The problem was that the cure didn’t work. Nancy couldn’t fill the hole in her parents’ lives. Ultimately, she had a terrible, unhappy relationship with her mother.

With a history like that, what did she wish for when she became pregnant? A boy. “I did feel, somehow, that having a boy would bring life back to my parents. That’s not the reason you have a baby, but I was really glad that I could have a boy.”

So giving birth to a boy stirs up feelings from the intergenerational history—and in Nancy’s case, tragedy—of a woman’s family. How did Nancy manage with all the history and ambivalence swirling around her? She found a personal reason for wanting a boy, one that worked for her alone, separate from the painful family history.

“I just celebrated his difference,” she told me. “I am a feminine woman. I felt I could be more natural with someone who was different from me. Maybe having a girl might have meant competition for me, and I hate competition for me.”

It is not just mothers who are full of feeling or who struggle with complex emotions over the prospect of a son. Practical issues are huge to men, especially since fathers are expected to be able providers and protectors. A father told me he had been “terrified” at the prospect. Another wondered: “How would I raise him? What to do about sports (I’m not a big fan), the military (I’m a veteran but didn’t want my sons to be subjected to the military)? How to deal with the challenges he would face regarding relationships, alcohol, drugs, et cetera? What to do about the circumcision question?”

For Ed, the prospect of having a son was complicated by his own painful childhood. He couldn’t imagine raising a boy who would be happy.

I was hoping for a girl. I wanted a girl because I grew up as a boy. I had the crap beaten out of me in middle school, and I was molested by a teacher. I didn’t want someone to go through what I went through. The disastrous part of all of this is that at eighteen weeks, when I learned we had a boy, I cried. I tried not to be upset. For me, it was emotionally hard. I just wanted to be happy that I had a child, and that it had ten fingers and ten toes.

But he found he couldn’t; the idea of raising a boy still made him sad. He tried to pull himself out of it.

I tried to focus on the fact that I’d always wanted a child before forty, and we did it five months before that date. But then seventh grade came back to me, memories of running out the door to escape, and I thought that was what was going to be in store for my son. Ultimately, I came to terms with the idea that I was being stupid about it. I have battled depression all of my life, and I had to realize that this child isn’t a clone of me.

This child isn’t a clone of me. It was precisely that thought that was so shocking to Andrea Buchanan and the other mothers who had been imagining raising daughters, not someone so profoundly different from themselves. For Ed the idea of raising someone exactly like him was deeply alarming. The idea of a son who wouldn’t have to be a clone of him was a relief.

Linda, the mother of an older girl, wanted her second pregnancy to bring another daughter. She felt at home in the world of girls—especially shopping for cute girl clothes—and, she said, “I wanted a second chance to do a better job with a girl.” Linda imagined herself becoming become the complete girl expert on her second go-round. It didn’t turn out that way. When the doctor delivered the news from the ultrasound, her husband was “ecstatic” and called his father. As for Linda, “I wasn’t thrilled. I really love him now, but it wasn’t a happy pregnancy for me.”

As every parent finds out sooner or later, you don’t always get what you have imagined. You certainly don’t get all that you wish for, and most of the time you don’t get what you fear. And in time you find a way to make your peace with what nature has given you. When I visited Ed and Mary five weeks after the birth of their son, Sam, Ed described his feelings at the birth of his son: “It was unbelievable. I was so excited, I cried a little bit. I was just so thankful that we got through it all and that our baby was healthy.”

What had happened to his fears of having a son, a son who might be condemned to a painful boyhood?

“I haven’t given a single thought to any of the issues that we talked about before,” Ed declared. Now, holding his son in his arms, it was all about having a healthy baby. “You know: ten fingers, ten toes, two eyes, one mouth, and all on the same head.”

Linda eventually moved beyond her yearning to shop for cute girl clothes. And, pregnant with her son in her early forties, she remembered that in her previous career as a teacher she had always enjoyed working with boys in the classroom, perhaps because her younger brother was developmentally delayed and she had been his “protector” when he was little. When Linda learned she was having a boy, she reached down, past her desires and her fears, to become the best mother of a boy she knew how to be.

All of her instincts came into play—including yet more “old tapes” shaping her imaginings. To her astonishment, she finds she can’t dress her baby boy in the yellow pajamas that his older sister wore, even if they fit him. The enlightened, educated woman in her is disgusted with her attachment to gender stereotypes. “I want to be able to put him in the yellow pajamas, but I can’t. I hate myself for that, that I have such box-like parenting. You can have had diversity training up the yazoo and still you are what you are.”

In other words, in the end you have to deal with the fact that you’re having a boy, that the culture has many demands to make on you and your son, and that we’re all stuck with an inner picture of what we imagine a boy to be. For Linda it is impossible to imagine putting her boy in yellow pajamas. For Ed it was originally impossible to imagine that he could give his son a good life. In his depressed feelings about his own boyhood, he didn’t think that a happy boyhood was possible. Now, with Sam in his arms, he is ready to start shaping a boy.

“As for the boy stuff, I’m trying to introduce him to good music, to play on the bass guitar,” Ed said when I visited him after Sam’s birth. He pointed to a guitar in the corner. “Do you know what that is?” I shook my head. “A ’76 Fender Precision.” I looked at the handsome instrument propped in the corner, glanced back at the infant in his father’s arms, and thought, Of course, just what every boy needs, because I know how important it is for a parent to have high hopes for his or her son. Not every parent dreams of his son loving a Fender electric guitar, but every parent has hopes for that child, and some fears as well.

IMAGININGS: A CLOSER LOOK AT OUR HOPES AND FEARS

The hopes and fears that parents experience about raising boys come from four sources. First and foremost, they arise from the history of a family over many generations and its many lessons, conscious and unconscious, about the nature and fate of boys and men. Second, they are the result of every person’s childhood experiences with boys. Third, they come from the deeply embedded cultural expectations of boys. Fourth and finally, they stem from current images of boys in the news, the entertainment media, and advertising. All these powerful forces shape what we believe our boys will want and need, and whether we think we’ll be able to provide it. They charge our sense of anticipation about this boy on the way and how we imagine he will take—or make—his place in the family.

What do the generational stories in your family tell you about the destiny and importance of men? Women have told me in therapy, “The men in my family haven’t done very well,” or “I come from a family of strong women,” where the implication is that the men are weak by comparison. What if you come from a family where many of the men have been alcoholics? What if your grandfather was a notorious philanderer, or perhaps a fantastically successful businessman who was totally self-absorbed and uninterested in his family? What if you’re divorced and your son’s father has been a painful disappointment?

Alternatively, what if your grandfather was a hardworking, churchgoing father who was home every night, talking with his kids over the dinner table? What if your husband hails from a long line of honest, industrious, caring men? Or perhaps he is bucking a family tradition of men who weren’t. There are many ways that men’s character colors the family story, and most of us can find both inspiration and cautionary tales in the family tree:

My father was my hero when I was young and still is today.

The men in my family for the most part are emotionally distant, controlling, and often disrespectful of others’ opinions.

All of them have made poor choices in their life (and they continue to on a daily basis). They do not learn from their mistakes, and they blame everyone else for their situation in life.

My father was the last of the great southern gentlemen. He was always respectful, well-mannered, generous, honest, and kind. I loved him dearly, but also saw him as relatively passive compared to my mother. I didn’t have brothers and I did not see my father as a strong masculine role model, so I feel like I’m charting new territory.

Aren’t we all charting new territory? Certainly. Yet as a child you would have heard stories about the virtues and vices of the men in your family over and over, and you have absorbed the lessons they teach: men are weak, men are reckless and die young, men are responsible, men sacrifice their family to their work, men sacrifice themselves to support their families. These lessons are inescapable.

We are all touched by the tragedies and triumphs of our families going back generations, and they propel us to want to raise a boy who will either match the historic triumphs of the men in the family or who will, at least, avoid the tragedies.

Euripides wrote, “The gods visit the sins of the fathers upon the children.” The fuller truth is that it isn’t just the fathers; it is the grandfathers and great-grandfathers as well. And it isn’t just their sins that affect future generations; it is everything good about them, too. How can I escape the legacy of my great-grandfather, a Congregational minister who raised four children of his own, adopted two black children, and wrote a newspaper column about religion and family life? He died fifteen years before I was born, so I never knew him, but I knew that my mother had loved him and my whole family admired him. My life has, unquestionably, been influenced by the image of that patriarchal figure born before the Civil War began.

But that is no different from every boy and every girl who is touched, often invisibly, by the history of the men in the family, whether the details of their stories have survived the passage of time or are simply reflected in history: the great-grandfather who immigrated to America, served in the military, survived the Great Depression, or didn’t. Whether your family legend offers a fully developed cast of characters or they have been lost to you for one reason or another, your mind reaches back to pick up the story line of the men in your family. Thus you mark the arrival of your son as one of them and begin to envision his future.

YOUR LIFELONG EXPERIENCES WITH BOYS

If the parenting experience can change your brain and fine-tune your mental reception for boys, the same can be said for other life experience with boys. Men themselves offer the most obvious evidence, taking in stride much of the routine boy behavior that drives their wives crazy. Wrestling? Pretend shooting with sticks and fingers? Dumb jokes about body parts? Men just don’t see the problem, or they tend to have a higher tolerance for what they see as fundamentally normal for a boy. The father of two young sons confessed that he was amused by his wife’s exasperation with such things. “The truth is,” he said, “I probably tolerate too much burping and body noises because I like watching her roll her eyes at the testosterone imbalance in the home.” A woman who has grown up with brothers or shared life with brotherly boys may have a similar comfort level with distinctly boy energy and expression.

Once at a workshop I ran for boys at an international school in Guatemala City, Guatemala, a teacher asked me, “Why do boys fight so much?”

“What boys, and what ages are you referring to?” I asked.

“My sons, they’re eleven and nine,” she replied. “They fight constantly.”

“What do you mean by fighting?” I continued.

“Well, they compete about everything—who is first in this and who is first in that,” she reported, both exasperation and concern in her voice.

“Do you consider that fighting?” I inquired, knowing from her worried expression that she certainly did.

“But they wrestle all the time…well, I don’t know,” she replied with uncertainty, because she saw that incessant competition and wrestling did not automatically qualify as fighting for me. “I didn’t grow up with boys—I only had sisters,” she said. “We didn’t do that kind of thing.” Of course not. Though sisters do fight and compete, they don’t show their competitive fervor and desire to win in the openly exhibitionistic ways that boys do. They almost never wrestle.

Living side by side with brothers is like prep school for parenting boys. If you are a woman who grew up with a brother, then you may remember his obsession with baseball cards or bugs, his preference for books or TV shows you could barely stomach, his sloppy, careless way of sharing household space, or his seemingly limitless capacity to amuse or annoy you. One woman told me that her brother shot her in the legs with plastic pellets from an air gun, which hurt a lot. (He is now the president of a nonprofit foundation committed to humanitarian work.) Whatever indignities you suffered at your brother’s hands, you have a ready-made frame of reference for becoming the mother of a boy.

Beth, who had raised an eleven-year-old daughter from her first marriage, was remarried and pregnant with a boy. She was quick to proclaim abject ignorance about boys. “I don’t even know what to do with a boy,” she said. “What am I going to do with him? I worry that he’ll ruin my house.”

But when I probed a little she immediately went back to her experience of her younger brother, Chris. She told me she wanted to build a separate playhouse in the yard so that her son could “trash the place, just like my little brother did.” How much did she remember about her relationship with her brother? Not too much, she claimed. “Chris was just the baby—we all doted on him, and all the sisters spoiled him.” She chuckled. “One time he set the woods on fire. And he was definitely a free spirit.”

If you are going to raise a boy, it is helpful to have known a brother who burned down six acres of forest, and to have watched your parents manage the consequences. Beth knew that in order to preserve her house, she should build a playhouse outside that her son could “trash.”

Or, as another mother shared, it is helpful to have grown up with brotherly boys on your block, “playing boy games—war, climbing trees, cowboys and Indians, baseball, et cetera,” leading you to conclude, as she did, that “I enjoyed it…and enjoy boy characteristics and encourage our son to be imaginative and fun-loving.” Or it is helpful to have had cousins like the ones that prompted this mother to write:

I had no brothers. I had male cousins who were fascinating to me and also unbelievably wild. Wildly out of control. They’d come from Chicago to visit us and furniture had to be moved and things had to be locked up. Seriously. They’d have boxing matches and huge screeching fights. It was terrifying but great theater.

If growing up with boys acquaints you with the periodic forays into wild behavior, it also makes you familiar with their vulnerabilities and anxieties. Watching your brother struggle with bed-wetting, night fears, or social isolation can help you prepare for the vulnerabilities that your son will display. “I paid attention to my younger brother a lot. I saw his pain in being misunderstood and getting in trouble all the time,” one mother wrote. “I would sneak into his room after he got in trouble to give a hug of support. I guess all that and seeing the struggles my ex-husband had have made me have such compassion for boys.”

If you had a brother who struggled with illness, you know how fragile they can be. “Despite our arguing,” a mother wrote of her brother, “I always felt that he reached out to connect with me during insecure times. At bedtime he would knock on the wall of his room, adjacent to mine, and we would do our own Morse code before saying good night.”

It is very common for boys to be shy, to avoid looking into the eyes of adults, to be reluctant to participate in the intense competition of town sports. If you are going to raise a boy, it is crucial to remember these things. Men may be tempted by the culture to remember their own boyhoods as heroic; it is helpful to remember the more tender truth. The memory of a weeping brother can counteract some of the cultural expectations of toughness for boys that I will be discussing shortly. It is useful for women, who don’t have personal memories of boyhood, to recall that they shared a home with an anxious brother, or perhaps shared the struggles of another boy they knew well.

Even among women with a rich store of experience with boys from childhood, the lessons they learned and carry with them about boys vary enormously, as these mothers’ recollections illustrate:

Having an older brother led me to like boys and to appreciate their impish, exuberant ways.

When I was a young girl, the few boys I knew were given to jokes about farts and boogers…not a great advertisement. The boys I was closest to in high school were the smart, nice guys. That is what I hope for in my son.

Brothers? Terrible relationship. Angry, even dangerous at times.

I was fortunate to go to school with some very nice boys. This was helpful in that I knew that not all guys were violent like my dad. I knew that I wanted to raise a son that was different from the men my dad’s age, and that is what I did.

Some women grew up around boys and learned to love them. Others grew up around boys and learned to fear, dislike, or distrust them. With or without brotherly boys, unless you went to all-girls schools, your assumptions about boys will be strongly colored by your early life with them in school and in your neighborhood.

CULTURAL IMAGES AND EXPECTATIONS OF BOYS

All of our hopes and fears for boys are shaped by the images and attitudes toward boys that surround us. Societal expectations for both genders are burned deep into our brains. The mother who could not bring herself to dress her eight-month-old son in yellow pajamas hated the idea that her reactions were so stereotyped, but her cultural training was so strong that she couldn’t disobey it. If she had dressed him in yellow and taken him out in public, it wasn’t just that she thought others would find it unseemly for him to be dressed in “girl” colors; she admitted that she found it unsettling, too.

We all have images of what boys are supposed to be and what they are going to like. Any nine-year-old boy will tell you: “Strong, tough, likes sports, doesn’t cry.” Many fathers, and some mothers, too, share that view. Even some who want their sons to live more fully expressed lives than the stereotype allows, often are unnerved by the thought that their sons won’t grow up to be strong and tough. They are frightened to have a son who might not fit the cultural mold.

Whether it is success in baseball or hunting or repairing a car in America, or in soccer in Brazil, or outstanding academic achievement in Hong Kong or Israel, men all over the world immediately imagine that their sons will be strong and heroic in recognizable ways. They hope that their sons will live up to the masculine ideal of the culture. For the most part, we wish conventional cultural dreams for our sons, sometimes to our own disgust, because the culture has filled our minds with those dreams.

I have had the opportunity to observe boyhood in many countries, and have seen that there are significant variations in what a culture requires of a boy. In many countries it is enough to be respectful of one’s parents and teachers and to be observant of the rules of your religion in order to qualify as a respectable boy. The cultural expectations for boys in the United States are comparatively narrow and cause many boys to struggle painfully with the feeling that they are lacking in some basic boy way because they do not enjoy what boys are “supposed” to feel and enjoy. It is difficult to be a boy in this culture because the demands for toughness and athletic prowess are so pervasive and many messages about being male are so mixed. Throughout this book I will address how to understand the pressures of cultural expectation and how to deal with them, especially if you don’t happen to have a son who fits them. And most of our sons do not.

IMAGES OF BOYS IN THE MEDIA

It is a scary time to raise boys in America. There was a time when media images of boy life reflected the kinder, gentler themes of Norman Rockwell portraits. The worst of our media concerns were the violence and bad-boy imagery of men in movies, TV shows, and commercials.

Today it’s not just the fiction of cinema, sitcoms, and commercials that delivers a disturbing picture of male life. Boys are in the news, making headlines that paint a grim picture of them as potentially violent or aggressive, self-destructive, disrespectful, impulsive, and problematic—a world of disaffected, alienated, lost boys seemingly mesmerized and mentored by screen violence and a hypersexualized pop culture.

The Internet now provides a place in which they express themselves as participants, creators, and correspondents on Web sites and in chat rooms and blogs; boys are eager players in sophisticated (but still largely violent) online, computer, and other video games. It’s a disorienting picture for parents, an exciting but also disturbing one, with the easy availability of pornography online and the presence of sexual predators there. Boys show up as eager, masterful, and vulnerable in new ways.

In the more than seven hundred interviews and surveys conducted for this book, nearly every parent and teacher mentioned concerns about aggression or violence, sexualized media, or the disheartening negativity of male imagery in boys’ lives today. Fathers and mothers alike voiced similar concerns:

Men are too often shown as stupid or brutes or both. The lack of respect shown to men and boys by society in general I believe makes it very difficult for boys to feel good about themselves and about being male.

I worry about what our society teaches boys about being men. I worry about the violence portrayed in the media, I worry about the sex portrayed in the media—it’s all over the place!

Incidents of boy violence in the news and the constant repetition of these themes can make you question the fundamental nature of boys and make you doubt yourself and your impact as parents.

HOW CAN I HELP YOU RAISE THE BOY YOU HAVE IMAGINED?

Let’s return to the two most important questions you’ll ask yourself for the next eighteen years or so: What do boys need? What is my son going to need from me?

To a great extent, the answer will vary from boy to boy and day to day; the combination of a child’s individual personality, temperament, and experience of himself and his world presents anew each day. There are, however, some ways in which all boys’ needs are the same and all parents can draw from the same well for wisdom. I want to offer the following four points as the foundation for successful parenting of boys. I think of them not so much as how-to tips, but as how-to-think perspectives for a parenting philosophy that continues to be relevant in different ways at every age and through every developmental passage with a boy.

First, you have to accept the reality that boys are different from girls. Second, you have to love the end product of a boyhood, that is to say, a man. Third, having acknowledged the gender of your child, you will need to step back and appreciate his uniqueness as a human being, because individuality trumps gender. And finally, you will have to surrender any lofty expectations of “making a man” of your boy. Nature will take care of that. You have an important nurturing role to fill in your son’s life, but you are not in charge of his development; development is.

As basic and self-evident as these points may seem, they can be profoundly challenging for parents. Many parents, mostly mothers, have told me that the experience of raising a boy has brought them up against their deepest beliefs about the differences between the genders and has challenged some profound prejudices they possessed about men that they were not fully aware they held. Fathers struggle differently but equally with basic issues. Parents and teachers tell me that it is not always easy to figure out what is a gender trait and what is individuality, and above all, it can be tough to embrace the idea that development is in charge.

Let’s consider these points one by one.

Accept That Boys Really Are Different from Girls

Obviously, what makes boys different from girls is their reproductive organs—the penis and the vagina, the testes and the ovaries—and the hormones that these produce, testosterone and estrogen. As the French say, Vive la différence. That is part of the picture, but not all. JoAnn Deak, a witty psychologist who has written about girls, proclaims, “The most gendered organ in the human body is the brain.” She is right. Scientific research in the past twenty years has confirmed that there are many, many differences in how the boy brain operates and how the girl brain operates, on average. As a parent, you are about to raise a boy with a boy brain, and if you are a mother, it will operate differently than your own brain does. If you are a father, your son’s brain may frustrate you in many of the same ways your own brain did when you were young. You cannot, even with single-minded effort and the best motives in the world, change a boy brain into something it is not.

That said, even though boys and girls have brains that operate in very different ways, children are children. When it comes to raising them, for the most part they need the same things: love, safety, guidance, challenge, understanding, and support. The brains may be different, but they are all young human beings. So if you are going to raise a boy, you have to remember that you are dealing with a boy brain, boy hormones, and a pace of development that is different from a girl’s. But please do not let the idea of the boy brain make you lose your common sense about what young people need.

We’ll look more closely at gender differences in the chapters ahead. For now, simply embrace the idea that you are raising a boy with a boy brain; welcome the reality and be open to discovering what that means, while never giving up your best, loving ideas of what a child needs.

You Have to Love the End Product: A Man

If you are going to raise a boy, you cannot just love him when he is little. You are going to have to like what he is going to turn into, namely, a man. I’m not saying you necessarily need to love your son’s father or have him around. That’s wonderful when it happens; however, there are a lot of single mothers in the world raising children without men to help them. Indeed, 35 percent of boys in the United States do not live with their biological fathers, and many of those mothers are doing a wonderful job without the daily help of a man. What I am saying, however, is this: if you are to be successful in raising a boy, you have to imagine the man he is going to become. Sometimes, with boys, that can be tough because on occasion it can be difficult to see the promise of the man in the boy.

One mother told me that when she first held her baby boy, she looked down at his body and saw “that he was such a perfect little man.” Her take on it was that his body looked just like her husband’s, she said, only smaller. And that made her happy, because she really loved her husband and admired the man he was. That’s an ideal situation, and not all women find themselves in it.

Men, too, especially those with disappointing fathers or those struggling with difficult lives themselves, often struggle to envision a hopeful model of a man for their son.

However, it is always possible to reach into your memories and find a man you have loved and admired. Was it your father? Was it your grandfather or maybe a brother? Was it a teacher or a coach you had when you were in school? Perhaps a character from literature or film?

What quality did you admire? Was it his playfulness, was it his steadiness? Do you have a photograph of him that warms your heart? If you want to stay in touch with what you are raising your son to be, then take that photograph of your “best man”—whatever man you love—and put it up in your son’s room. It will be a good reminder for you and a wonderful conversation starter for him as he’s growing up: “Why do you have that picture up there, Mom?” “That’s the kind of man I’d like you to grow up to be; he was strong and kind,” or “He loved the outdoors and taught me to love it, too.”

The legacy of good men, or even of flawed men’s good moments, is lasting, as the mother we met earlier, whose father died when she was young, shared:

I am lucky in that I have many memories of him. I remember him playing goofy games with me and my sister—doing funny tricks, taking us places, showing us off at work…He seemed huge to me—and funny, smart, a little goofy, and very kind. I married a man just like him. It’s only in writing this that I’m realizing how huge an impact my dad really has had on me—despite the fact that I barely had a chance to have a relationship with him.

The kind of man you want your son to be has already lived a good life. You knew him; he was in your family or in your school. Find him in your memories and let him help you guide your son.

Love the Son You’ve Got

So much of life in our competitive culture is required to be strategic and performance-or outcome-based, it is tempting to apply the same approach to parenting. With hopes of producing the best boy ever, we might set out to cultivate the best of traditional male attributes (smart, strong, steady, uncomplaining), but then perfect him by adding the quality of emotional literacy and subtracting violence and excessive aggression so he can be successful in life. Many caring parents speak about parenting as if it were a giant school project: if you just start soon enough, read the right research, and do the right things, you can get the particular end product you have in mind. One reason I don’t like to hand out a lot of “do this, do that” advice is that the cumulative effect of all that advice is demoralizing when the child himself gets lost in the flood of helpfulness. With so much to “do” to make your son into who he “should be,” when do you have time to let him teach you about who he is?

Your job as a mother or father is not to invent or create a better kind of boy who will develop into a more highly evolved man. If you try to do that, you will fail, and your son will resist you because he does not want to be your creation.

Whatever your imaginings about the boy on the way, your son is already busy becoming himself, expressing himself. If you are well along in your pregnancy and he is making himself felt, perhaps you already think of him as an active baby or a mellow one. That’s fine. But stay tuned. Your job will be to welcome your son wholeheartedly into this life and wait for his temperament, his individuality, and his special gifts to emerge. At every age, the best thing you will ever do for him is to support those unique parts of him that you cannot even see yet.

Trust in Development

The textbook definition of child development is “the sequence of physical, cognitive, psychological and social changes that children undergo as they grow older.” Child development is true interdisciplinary science that attempts to describe and explain everything we observe in children of different ages. It is the foundation of this and every parenting book. As sophisticated as developmental science has become, however many powerful theories it has developed, it does not yet have all the answers to the fundamental questions of what makes children grow the way they do.

We do not know, for instance—and you may find this hard to believe—exactly why boys and girls are different or how different they really are, or even whether parents are the most important influence in their children’s lives. Researchers are still fighting over these and other fundamental questions. There is no absolute scientific answer to some of the most basic—and sometimes baffling—aspects of boy life. What makes it so hard for little boys to sit still, when little girls typically are able to do so? Is it a biologically driven behavior arising from male hormones? Is it the result of a difference in the amount of serotonin in the brain? Is it the result of watching too much television or a result of the kind of play boys engage in? We have theories, but we don’t know for sure, so we have to trust that there is some wisdom at work in nature. We have to trust development.

Indeed, trusting boy development is the leitmotif of this book, a thread running through every chapter. Why do I urge you to trust development when neither I nor child development research can tell you for sure why something is happening? Because I have spent a long career as a psychologist watching development at work and I have heard thousands of children describe the story of their own growing up. Even if we do not totally understand it, it is a reliable process. More than that, it is an almost miraculous process, an intricate blending of biology, culture, family, and personal experience out of which arises a totally unique individual, a human being very much like all other human beings and yet completely different. And from the point of view of a psychologist, what is interesting is that every child—every boy—has a unique story to tell about his development and how he experiences his maleness, his parents, the television shows he watches, his hormones, the classroom he spends his days in, his troubles and his joys.

The most reliable person to tell us about his experience would be your son. Since I cannot personally talk with him, and because he will not always be able to explain things clearly to you because he is too young or inarticulate, I am hopeful that in the chapters ahead I can introduce you to boys whose conversations about their inner lives will illuminate some of your son’s experiences and make them more understandable. And once you understand why boys, including your son, do things the way they do, you will, I hope, come to understand boys more deeply and trust in their development.

As a parent, it’s often hard to trust development. You will want to make things happen that aren’t yet happening because development is not ready. You will want to stop things from happening that are occurring before you are ready. You’ll hear a lot about supporting development by trying to ramp it up—like SAT scores—with special developmental toys and activities. All this may give you the impression that you’re in charge of development, driving it. You are not. Your son’s development will be his own to live, his to manage, his to determine. Right now, as you ready your home, your family, and yourself for the arrival of your son, it’s a good time to get used to the idea.

NOW IMAGINE YOURSELF: THE PARENT OF A BOY

Imagining is a full-time preoccupation for most expectant mothers and fathers, and it continues for the rest of your life with a son. At every age and at every turn, all your questions about your son’s future will have you searching the tea leaves of your family, history, and culture. What are the signs that he will be a happy and successful man? Will he be a good husband and father? Will he have close friendships? Will he be close to his mother? And finally, how do you, as his mother or father, raise the healthiest, happiest, strongest—and I mean strong in character—son that you can possibly raise?

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, the French poet, wrote, “To live is to be slowly born.” Your son is going to be slowly born through the years to come. And you will have a front-row seat on the miracle of his development.

If you are expectant and taking good care of yourself, getting the proper nutrition, and avoiding alcohol and drugs that are known to affect fetal development, you are already being a good parent, supporting your son’s healthy start. Once in the world, some of his development and his identity will be the result of forces in society, reactions to friends, television shows, and video games that you might hate. You will have a lot of control over these influences when he is very little; later on you’ll just have to watch it happen. He may want to wear his blue jeans hanging off his butt with his boxer shorts showing—or whatever the fashion is sixteen years from now—because that’s what his friends are doing. You can shut off the electronics when he is little, but at a certain point he can go over to someone else’s house to watch TV. You will be sidelined over many years.

Some of what he is going to be will come from sources in the family: your parents, your in-laws, and of course your spouse. You’ll have more say in this arena than in others, but you cannot always make your family do what you want them to do, can you? (If you can, please write and tell me your secret. My e-mail address is in the back of the book.) Many of the early experiences in his life will take place in school. He will fall in love with some teachers, hate others, pay too much attention to his classmates and not enough to his studies. And much of it you won’t be able to see because it will take place behind the closed doors of school.

Finally, when all the other influences in his life, biological, educational, and social, are done, you are going to have a personal, intimate, one-on-one relationship with your son that is like no other. If you are a mother, I can assure you that it will be the most important relationship in his life except for the one with his father. And if you are a father, your relationship with your son will be the most important one in his life except for the relationship with his mom. Well, you understand—no one can ever quantify which is the most important relationship in a life except the child himself, when he grows up, but mothers and fathers usually head the list.

It would be a shame to miss the opportunity to be a huge and loving influence in your son’s life. It would be a tragedy not to love him to the fullest extent of your ability and have him carry that love with him always. The desire to see your child thrive and have a good life has to be at the center of every parent’s heart and fulfillment. You wouldn’t be reading this book if you didn’t feel that.

If you are going to be the parent of a boy, you might as well prepare yourself for an amazing adventure, as if you were a small child clambering onto the back of huge winged dragon. He—and I mean this dragon of a boy, of course—is going to take you places you never imagined going. He is going to bounce you up and down, and you may be a little frightened. When he steps onstage with his friends in front of the entire middle school to sing the rap song they wrote, when he gets absolutely terrified on a ride at Disney World that you imagined would be fun, when he makes a football team or strikes out in a Little League game, you may be sharing joys and sorrows you have never known in your own life.

If you are a woman on the back of this dragon, you will swoop down to earth and see things in an entirely new way, through the eyes of a boy. For a mother, raising a son is the closest you will ever come to crossing that unbridgeable gender line. When your little boy grabs his penis because he has to pee, when your eight-year-old rails angrily over a hurt as he tries to hide tears, when your thirteen-year-old lies right in your face, when your older teen who has been lifting weights at the gym strikes a pose to exhibit his muscular physique, you’ll get it. Loving a son will make you empathize with boys and men more than you ever thought possible. All the while you are teaching him, by example, about women and how they think and feel, you will be learning a lot about what it is to live the life of a boy.

If you are a father, you are going to rediscover everything about your own boyhood from a different angle, and it will be disorienting to you. Your assumptions about what all boys love, because they were what you loved, will be tipped on end because he won’t be exactly like you; he will be passionate about other things. At other moments you will know exactly what he is feeling and some old, terrible boyhood pain or thrill will wash over you. If you are fully open to the experience of fathering—that is to say, if you have some humility—you will, at times, respect him and doubt yourself. Your son will, at times, make you feel like a little boy yourself. He’ll make you rethink who you are and everything you have done.

Our focus in this chapter has been on imaginings: all the ways you anticipate a boy and life with a boy, and begin to understand the developmental journey that lies ahead for him. But this time is also about imagining yourself as a parent, and your own developmental journey as a parent, specifically the parent of a boy. So as you witness your son’s developmental progress, and some inevitable struggles, in the years to come, appreciate that you, too, are growing, from the parent of your imaginings into the parent you want to be.

An expectant mother wrote to me: “To be honest, I wasn’t nervous about raising my boy until after I read your book Raising Cain! Ha—now I am aware of what happens with young boys, and scared of what awaits our family.”

Please don’t be afraid. It’s just a boy.

Keep in mind this piece of wisdom shared by a mother who recalled her worry about having a boy. “I shared my fear with my mom, who wisely told me, ‘You’re not having a boy. You’re having a baby. And boys love their mothers. You’ll see.’ She was absolutely right.”