A trip in a time machine to Earth of 4.5 billion years ago would not only be eerie; it would be perilous. With an atmosphere lacking free oxygen and raining acid, you’d need a space suit far beyond the technology of modern science to survive. Impact after impact of rock and ice from space made the surface sometimes roil at thousands of degrees Fahrenheit. With this heat, there were no oceans: liquid water may have formed a few different times, only to evaporate away. As a break from this desolation, you might hope for beautiful moonlit nights. Forget about it. There was no moon.

Artifacts of the transformation of this primordial world into our modern one are strewn across different bodies of the solar system. Six missions landed on the moon and returned samples to Earth. Carrying mini geological kits, astronauts collected rocks from craters, highlands, and lowlands of the lunar surface. The specimens are today stored in liquid nitrogen in repositories in Houston and San Antonio. A number of small moon fragments have been given as gifts to foreign dignitaries, while others grace public exhibits. The bulk of the rocks, about 850 pounds in all, remain to be studied. The few samples that have made it to labs tell important stories of the origin of our world.

One of the biggest lessons from moon rocks is how normal many of them are. In terms of mineral content and structure, moon rocks are more similar to those on Earth than others in the solar system. One similarity is particularly telling. Oxygen atoms can exist in different forms, defined by the number of neutrons in the nucleus. By measuring the neutron-heavy and neutron-light versions of oxygen in any rock, a very informative ratio can be calculated. Each body in the solar system carries a unique chemical signature written in the proportion of different versions of oxygen in their rocks. The reason is that the oxygen content inside a planet’s rocks is sensitive to its distance from the sun when it formed. The oxygen composition of moon rocks, though, is virtually identical to those of Earth. This means that the moon and Earth formed at the same distance from the sun—perhaps in the same orbit.

With all of these similarities, there remains one very significant difference between moon rocks and those of Earth. Moon rocks almost entirely lack one class of elements, the so-called volatiles. These elements—nitrogen, sulfur, and hydrogen—share one important geological fact: they tend to vaporize when things get hot (hence the name volatiles). Some great event in the distant past must have baked the moon rocks, releasing their volatiles.

The lessons of the moon rocks are clear—the minerals on the moon formed at the same orbital distance from the sun as Earth and then suffered some kind of blast. What do these facts tell us of the origin of the moon?

The current theory for the formation of the moon envisions something like a cosmic demolition derby. In these automotive mosh pits, common at fairgrounds in the 1970s, cars intentionally smashed into one another, with the last car running being the winner. Along the way, cars would slam into each other with wild abandon. The most violent of these collisions would eject the light outer layers of the cars, hubcaps and bumpers, leaving the inner ones hopelessly entangled.

This type of collision offers an insight into how the Earth-moon system came about. Over 4.5 billion years ago, a large, perhaps Mars-sized, asteroid is thought to have collided with the forming Earth. Much like the twisted mélange of car parts in a demolition derby crash, the collision ejected lighter parts of each body while the heavier pieces fused. The lighter debris, consisting of dust and smaller particles, now depleted of volatile elements, began to orbit Earth as a disk. Over time, this debris disk coalesced as the moon. The cores of the two bodies did not propel into space but liquefied under the great heat of the impact, only later to cool and solidify as the new core of Earth. In addition, the impact so whacked Earth that it left a 23.5-degree tilt in its axis of rotation.

Initially, there were two large bodies in the same orbit of the sun. Then they collided, forming what we know as Earth and moon today. Ever since that impact, the two bodies have been locked in an orbital dance—Earth and moon exert gravitational pull on each other, while the laws of physics and momentum tie the speed of the spinning of Earth to the rotation of the moon. The impact on our lives is as straightforward as it is profound: the length of days and of months, like the workings of the seasons, derive from the Earth-moon system. Every clock and calendar, like the cells of our bodies, holds artifacts of a cataclysm that took place over 4.5 billion years ago.

The Romans had an effective way of controlling troublesome officials in the far-flung regions of their empire. Instead of gerrymandering districts to stay in power—to help friends and get rid of foes—Caesar and his cronies found the ultimate way to retain control. They gerrymandered the calendar. Have a political friend in one region? Add a few extra days to his term. Want to get rid of a foe in another place? Lop days of his rule off the year. This was wonderfully effective; however, over time, not only did the decentralized calendar make ruling difficult, but the year became a patchwork of political kludges, fixes, and compromises.

The nature of Earth’s rotations in space makes it ripe for these kinds of abuses. We all learn this material in school, but most of us forget the meaning of the planet’s rotations by the time we are in college. A recent survey of Harvard undergraduates asked the simple question: What causes the seasons? Over 90 percent of them got the answer totally wrong. The answer has nothing to do with the amount of light that hits Earth during winter and summer, nor with Earth rocking back and forth, nor with the planet getting closer to the sun over the course of the year.

As we’ve known since the days of Copernicus and his contemporaries, the moon rotates around Earth, while Earth retains its constant 23.5-degree tilt as it rotates around the sun. The angle that sunlight hits the planet changes at different parts of the orbit. Direct light generates the long days and heat of summer; tilted and less direct light gives us shorter and colder winter days. The seasons aren’t generated by Earth rocking back and forth; they derive from the planet having a constant tilt as it rotates around the sun.

Because of the different orbits that affect our lives—ours around the sun and the moon around us—there are choices to make when constructing a calendar. Of course, the length of a year is based on the rotation of Earth around the sun. If we know the longest and shortest days, we can carve up the year into months based on the seasons. Another way to do this is to base the calendar on the position of the moon as it goes from full to partial to new every twenty-nine days. The problem is that you can’t synchronize a lunar calendar with a seasonal, or solar, one. The number of lunar cycles does not correspond easily to the number of seasonal ones.

So what do we do? We add fudge factors. Julius Caesar’s calendar had a leap year every three years to keep the months in line with the seasons. The problem with this calendar for the Catholic Church was the extent to which the date of Easter wandered. To rectify this situation, Pope Gregory XIII initiated a new calendar in 1582. Italy, Spain, and a few other countries launched it immediately following the papal bull, resetting October 4, 1582, to October 15, 1582, losing eleven days. Other countries followed to different degrees. Britain and the colonies, for example, only accepted it in 1752. One of the most important issues to iron out, naturally, was when to collect taxes.

Years, months, and days can, at least in theory, be based on celestial realities, but minutes and seconds are mostly conventions. Our calendar has seven days because of the biblical story of a six-day creation, followed by a day of rest. Minutes and seconds are in units of 60 due to a matter of convenience. The ancient Babylonians had a number system based on 60. It turns out that 60 is a wonderful number because it is divisible by 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

Humans are a timekeeping species, and much of our history can be traced to the ways we parse the moments of our lives. These intervals are based as much on astronomical cycles as on our needs, desires, and the ways we interact with one another. When the necessities of shelter, hunting, and survival were highly dependent on days and seasons, humans used timepieces derived from the sun, moon, and stars. Other early timepieces relied on gravity, with hourglasses that used sand or water clocks such as those first seen in Egypt in 4000 B.C. Our need to keep time has itself evolved; an ever-increasing necessity to fragment time corresponds to the demands of our society, commerce, and travel. The concept of moments parsed into seconds would have been as alien to our cave-dwelling ancestors as seeing a jet plane.

There are clocks in our world that do not rely on convention, political choice, or economic necessity. The DNA in our bodies can serve as a kind of timepiece. Averaged over long periods of time, changes to some parts of the DNA sequence happen at a relatively constant rate. This means that if you compare the DNA structure of two species, you can estimate how long ago they shared an ancestor, because the more different the strands of DNA from two species are, the more time they have changed separately. As we’ve seen with zircons, atoms in rocks also tell time. Knowing the ratio of different versions of the elements uranium, argon, and lead can tell us how long ago the minerals in the rock crystallized.

The different clocks in bodies and in rocks don’t tick independently; they are part of the same planetary and solar metronome. Comparisons of the DNA inside humans, animals, and bacteria speak of a common ancestor of all three that lived over 3 billion years ago. This is roughly the age of the earliest fossil-containing rocks. The broad match of dates from rocks and DNA is all the more remarkable given how the rocks have been heated and heaved over the same billions of years that DNA has mutated, evolved, and been swapped among species. Agreement between these different kinds of natural clocks leads to confidence in our hypotheses. On the other hand, discordance between the clocks in DNA and those in rocks can also be the source of new predictions. Whale origins are a case in point. With some of the largest species on the planet, blowholes in the middle of their heads, ears specialized for a form of sonar, and odd limbs, backs, and tails, whales are among the most extreme animals on Earth. Yet, as observers have known for centuries, their closest relatives are mammals: they have hair, mammary glands, and innumerable other mammalian affinities. But which mammals are their closest relatives, and when did whales enter the seas? Comparison of the DNA of whales with that of other mammals revealed that whales likely diverged from odd-toed ungulates such as hippos and deer. The differences in the genes and proteins implied that the split happened nearly 55 million years ago. But this created a whole new puzzle for paleontologists. Not only were there no fossils that showed transitional organs in the shift; there was nothing that ancient with whalelike features in the fossil record. The gap served as a challenge. Vigorous paleontological exploration brought confirmation: the discovery of whale skeletons with ankle bones similar to those of hippos and their relatives inside rocks over 50 million years old. And it all happened by relating the different clocks in rocks and DNA.

Rocks and bodies contain more than clocks: they also hold calendars. Slice a coral, and you will find that the walls of the skeleton are layered with light and dark bands. As they grow, corals add layers of mineral to their skeletons, almost like slapping plaster on a wall. The ways that the mineral forms depend on sunlight, so the variation in the layers reflects the waxing and waning of each passing day. Mineral growth is fastest in summer, when the days are long, and slowest in winter, when the days are short. Consequently, bands deposited in summer months will be thicker than those at other times of the year. Count the number of layers embedded in each cycle of thick and thin layers, and what do you find? Three hundred sixty-five of them. Coral skeletons can be an almanac of days of the year.

The beauty of corals lies not only in the reefs that reveal the splendor of the underwater world but in the insights they give us into our past. Crack rocks along the sides of roads in Iowa, Texas, even north into Canada, and you will see coral reefs that once thrived in ancient seas hundreds of millions of years ago. The city of Chicago is built upon an ancient coral reef. And reefs like these tell the story of how time itself has changed. Go to fossil reefs 400 million years old, and you will find four hundred layers inside the corals—suggesting that each year was actually four hundred days long and contained a whopping thirty-five more days than our current year. What accounts for this discrepancy? Since the duration of a year is fixed by Earth’s rotation about the sun, the days must have been shorter 400 million years ago than they are today. To make the algebra work, each day had to have been twenty-two hours in length. In the eons since those corals were formed, two hours have been added to every day.

Like a slowing top, Earth spins slower and slower with each passing moment, making days longer now than in the past. As the planet rotates, the water in the oceans moves about and serves to brake the spin of the planet. That is why today is two milliseconds longer than yesterday.

Fossil corals are silent witnesses to the lengthening of days. Clocks and calendars abound in the natural world, sometimes in the most surprising places.

In the rush of pitching my tent, I inadvertently left a hummock of tundra under the floor. With a mound in the center and slick nylon surfaces inside, my sleeping bag slid to one corner each time I drifted to sleep. After a frustrating few hours of writhing like a pupa in a cocoon, I became determined to find a flat surface, and in a fit of fatigue and desperation I jury-rigged one by contorting myself over heaps of clothes, books, and field gear. It was a good thing we expended a lot of energy that first day setting up camp; my exhaustion led me to a reasonable facsimile of sleep.

I arose to the bright morning sun and dressed quickly, not wanting to hold the team back. Today would be our first day in Greenland looking for fossils, and the excitement made me surprisingly alert despite the fitful rest.

I made my way to the kitchen tent, my first goal being to get the coffee going. Our field gear was packed so tightly for the trip north that simply finding the breakfast containers was no small task. After about ten minutes of fumbling with the packing lists and crates, I broke out some cooking supplies and got the java brewing.

Life was good. It was a clear, bright Arctic summer morning. The dry air made images incredibly sharp; features in the distance looked as if they were right next door even though they were miles away. Warming my fingers against the coffee mug, and relishing the stillness, I walked in my mind through the different hills I was going to hike that day.

After a few cups and about twenty minutes of savoring the calm, I realized something was wrong. The world was still, a bit too much so. With each passing minute of silence, I began to feel more alone.

A glance at the clock revealed the cause for my solitude: it was 2:00 a.m. Yet here I sat, fully dressed, primed for a whole new day, and bristling with energy. I felt like a total chump, albeit a well-caffeinated one. Returning to sleep was an impossibility, so I broke out a novel I was saving for a snowy day and struggled to read for the next few hours until my companions arose.

It was the light, of course. The walls of my tent did not block it out, leaving the inside illuminated at all hours. My brain, acclimated to the southern world, was completely in tune with the equation “light equals day and dark equals night.” Because that simple relationship was lacking in the twenty-four-hour daylight of Arctic summer, my brain’s usual cues were utterly useless. My sleeping colleagues, old hands at fieldwork, prepared by bringing eyeshades, while all I had was a flashlight.

Those first few days were a real jangle. I felt off-kilter, as if the insides of my body were struggling to keep up with a whole new planet. Think of a major case of jet lag, but without any night whatsoever, the only reference point comes from a clock. The longer I dwelled in the landscape, though, the more my brain became attuned to it. The sun traces a large ellipse through the sky, casting different shadows throughout the day. Almost without thinking, the brain begins to make a sundial out of any standing object. Of course, in the high Arctic we lack trees; any large rock or tent ends up doing the job.

From jet travel we all know that our sleeping and wakefulness are matched to the sun. Virtually every part of us—every organ, tissue, and cell inside—is set to a rhythm of day and night. Kidneys slow down at night. That’s a wonderful trait if you want to minimize trips outside bed—something very useful when inside a sleeping bag in the Arctic. Body temperatures vary over the course of the day, with the coolest ones happening at 3:00 a.m. Liver function is time dependent as well: the human liver works slowest in the morning hours, meaning the cheapest dates would be at breakfast.

Our bodies respond to more than days; they also are tied to seasons. The changes from winter to summer bring new patterns of light, temperature, and rainfall. Animals are tied to these in the ways they feed and reproduce, and humans are no different. Even our moods relate to the season. By some estimates 1.4 percent of Floridians suffer from seasonal affective disorder, compared with 14 percent of New Hampshire residents.

Drunks see time flying by, with the party just getting going as everybody leaves. Cannabis brings an eternity to a twenty-minute episode of The Three Stooges. Intense concentration or emotions make us lose track of time. Even the proverbial “watched pot” that never boils is a statement about how our perception of time is sometimes at odds with the clock itself.

In 1963, a young French geologist had a plan to change the way we think about time. By the age of twenty-three, Michel Siffre had visited some of the largest unexplored patches of Earth. These were underground, and by mapping the world below, Siffre revealed vast caverns and glaciers inside the Alps. The subterranean landscape is a beautiful and dark world, and in this void Siffre was inspired to ask a whole new question.

What happens when people completely disconnect from the clock? Each of us is a slave to it: we chop our days into little moments and plan our lives around them. Not only do we live in a world defined by natural time—the dark of night and the light of day, the warmth of summer and the cold of winter—but we have inserted man-made inventions into this equation. Beepers, buzzers, and alarms tether us to each passing moment. What happens when we completely cut the cord that binds us to these stimuli?

Siffre intended to be his own lab rat and concocted a plan to live for two months in a cavern two hundred feet belowground, completely removed from normal human existence. He would bring food, a sleeping cot, and artificial light, but—and this is the important point—no timepiece or anything that could even indirectly give a clue as to time. Siffre’s only connection to the outside world was a telephone with which he called his friends on the surface to inform them of the times he spent awake and asleep. The plan was for a sixty-day disconnect from the normal light-dark cycles of our world and from our clocks that are based on them.

A meticulous note taker, Siffre dutifully recorded each passing day on a calendar with his bodily functions and mental states. His diaries record his daily movements, his body temperature, his mood, and his libido.

On the thirty-seventh day of his records, with twenty-three days yet to go, Siffre was on the phone with a colleague from above. Pierre, one of his chums, asked, “How much time in advance do you want to be warned that your experiment is about to end?”

“At least two days to gather up my things.”

“Start getting ready,” Pierre responded. The experiment was over. By relying solely on his mental clock, Siffre had lost twenty-three days.

What happened?

One answer lay inside Siffre’s diaries. Having recorded when he woke and went to sleep, he called his friends when he was able so that they could log the real time for him. But lacking a watch or alarm clock, he had no idea how long each interval of sleep really was. What he perceived as brief ten-minute catnaps were in reality eight-hour slumbers.

His misperception of time ran deep. At one point in the experiment, Siffre called his friends to see if he could mark off two minutes simply by counting. Most of us can pace this off roughly, within ten seconds or so. Siffre began counting from 1 to 120, in an attempt to march off the seconds in two minutes. This simple task took him five minutes.

When the team crunched the numbers in Siffre’s diary, they came to a fundamental realization. The hours of Siffre’s biological day, when he slept and was awake, were not some wandering, random affair. The number of hours he slumbered and those he was awake almost always totaled close to twenty-four. A rest-activity cycle of twenty-four hours is a close approximation of life on the surface. Siffre’s perception of time underground was completely off, but his bodily cycles marched along at an earthly pace.

Word of Siffre’s feat ignited a fad of isolation research. In the years since his time in the cave, volunteers have endured sensory deprivation while gizmos recorded their vital signs, brain activity, and behaviors. Some have sat for weeks or months in chambers with light either restricted or tightly controlled. Other people have attempted the truly extreme, like the sculptor who entered an isolation experiment in a chamber with the goal of living in complete darkness for months. That experiment had to be scuttled after only a few days when he started to lose his grip on reality.

Through all of this sensory deprivation, one consistent pattern emerges. Many of the biological urges we experience—sleep, hunger, and sexual cravings—cycle at a regular pace regardless of whether we live in a dark cave, room, or any other isolated environment. Time exists on the clock, in our perceptions of it, and somewhere deep inside us.

Curt Richter had an inauspicious beginning to a scientific career. After a stint in the army during World War I, he entered the Johns Hopkins University to explore the extent to which animal behaviors are based on inborn instinct. He arrived in Baltimore in 1919 to work with a senior scientist already famous for his work in the field. Unknown to Richter, his new adviser had an offbeat way of training students. Richter was given the usual trappings of a graduate student’s existence: a little office in which to study, a library card, and some supplies. Once established with his kit, Richter was left completely on his own. Each day consisted of no set meetings, no required courses, no seminars; it was an existence with no structure whatsoever. There would be no babying, for this was a sink-or-swim introduction to a scientific career.

Soon after Richter established himself in Baltimore, his adviser handed him a cage with twelve normal rats inside. His instruction to Richter was as simple as it was intimidating: “Do a good piece of research.”

Richter began by feeding the rats some bread and staring at them for days on end. Like a good scientist, he started to record details about their daily lives: when they ate and what they did. Then one day he made the observation that changed his career and ultimately launched an entire new field of science. As he reminisced years later, when describing his rats, “They just jumped around the cage for long periods and then were quiet again.”

The rats clearly had set times of activity and rest and of hunger and satiety. Richter began to fiddle with things a bit. Once he had a reasonable idea of their activities, he started to leave the lights on in the lab overnight. Then he would turn the lights off for days on end. The activity patterns of Richter’s rats stayed on track. The rats responded in the way the caveman Siffre did years later.

With that simple observation, Richter saw in these rats the question that was to become his lifelong obsession: What was the basis for these innate daily rhythms? What controlled them?

Richter turned to studying blind rats. With no obvious cues to perceive light and dark, these animals retained set daily patterns of sleep and feeding. He postulated that there must be something inside, some clock that keeps things ticking along. If so, where in the body did it reside?

The first candidates were the glands that secrete hormones controlling heart rate, breathing, and other bodily functions. Richter gave the rats chemicals to disrupt their hormone balance, then altered their diets, and later he even took out the glands to see what happened. He performed more than two hundred of these kinds of experiments over the years. And in every case, he got the same result. No matter which part he removed, or which hormone was blocked, daily patterns of activity just ticked along normally.

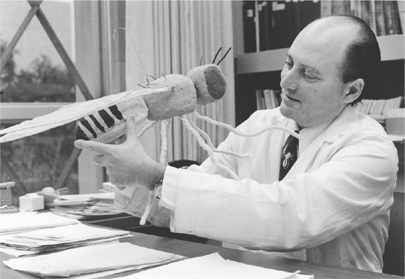

Richter turned his attention to rats’ brains and nerves. He systematically lopped off pieces of the rats’ brains to see the effects. In 1967—forty-eight years after his adviser’s gift of the cage—Richter removed one little patch of tissue at the base of the brain. Excision of a fleck of cells not much bigger than a grain of rice obliterated virtually all of the rhythmic behaviors in the rats. The rats’ internal clocks were in a tiny field of cells right behind the eyes, later named Richter’s patch.

How could a bunch of cells keep time? Answers to that question were to elude Richter and his brute-force approach of removing pieces of the body. The key came from an entirely different approach to science.

Genetic mutants are the stuff of biology: six-toed cats, two-headed snakes, and conjoined goats are not just curiosities; they have the power to tell us the fundamentals of how bodies are built and how they work. While mutants tell us which genes have gone awry, their scientific importance lies in how they reveal what normal genes can do.

Let’s say you find a mutant animal that lacks eyes. Clearly there is some genetic difference between mutant and normal animals that causes eyes to be missing. There is a lot of work to be done to isolate the actual genetic defect. But by doing breeding experiments between the mutants and the normal animals, you can ultimately identify the gene itself and, if you are really persistent, discover the actual stretch of DNA involved. Knowing the DNA is a key to understanding the molecular machinery that controls how eyes are built. The same is true with virtually every gene that acts to build bodies.

Scientists have scoured populations looking for mutants. Careers have been made, and Nobel Prizes won, by cataloging mutants or by finding just the right one with an extra toe, different jaw, or oddball eyes, limbs, or heart. While the rewards can be high, this approach is often like rolling the dice. Some mutations crop up only once in every 100,000 individuals. Unfortunately, the creatures we are most interested in, mammals like us, are the hardest to work with, because they take a longer time to develop than other creatures, they take more resources to rear, and they spend most of the critical phases of their development hidden from the outside world inside the female.

Because of these difficulties, for the past hundred years, flies have been the best animals in which to study genes. As opposed to mammals or reptiles, for example, you can get lots of flies: they reproduce and develop fast. With such a steady supply of embryos and an entire community of scientists doing the research and sharing data on them, an enormous number of different kinds of mutants have not only popped up in labs but been cataloged, described, and stored for others to study.

But why wait for nature to produce mutants when you can make them? The process of mutating DNA is relatively straightforward, on paper at least. First, you take some flies and treat them with chemicals or radiation that interrupts the copying of their DNA. With altered DNA, a variety of mutants emerge in the next generation. In flies, the wait from one generation to the next is only about a day. Then scan the mutants for whatever trait you are interested in. Some will have bizarre legs, others mutant eyes, and so forth.

By the late 1960s, Seymour Benzer’s laboratory at Caltech had become a hub for the study of mutant flies of all sorts. A young student, Ronald Konopka, entered with a plan and the desire to take some risks making mutants. Benzer’s lab was interested in looking at behaviors, and by the time Konopka set to work, Benzer’s group had already accumulated mutants with odd reproductive and courtship dances.

Konopka had a plan to use this same approach to unravel the genetic workings of the clocks in the body. Smart money at the time was against his success. Most scientists thought the body’s clock was just like a stopwatch and way too complex to dissect easily.

Konopka had come to the right place to make inroads into this problem. Seymour Benzer had a personal motive to understand body clocks. He was a notorious night owl, working late hours in the lab, yet his wife was in bed soon after dinner. Perhaps mutant flies could provide help to a marriage where the partners interacted with each other only at dinnertime.

Konopka spent what must have seemed like a near eternity looking at developing flies. Flies hatch from eggs as maggots, feed for a bit, then develop hard cases around their bodies from which they later emerge as metamorphosed flies. Flies emerge from their cases in early morning, at the time of day when it is normally coolest. This behavior is a manifestation of their internal clocks; flies reared in artificial light-dark cycles will always emerge at the end of a dark cycle, when their brain is wired to expect the cool of dawn.

After about two hundred tries at making mutants, Konopka found one batch of flies that were completely messed up: some emerged too early from their cases, others too late, and still others at random times during the day. The differences in time emergence almost certainly reflected some sort of genetic defect. Here was a defect that reflected a possible clock mutation.

The lab bred each type of fly selectively with another of the same type, making whole family lines of the different mutant flies. With these lines, Konopka and Benzer set the stage for understanding the molecular machinery that keeps time.

Like any good gene, Konopka’s makes a protein that does the real work in the body. Knowing the gene means that you can ask the important question: Where and when is the protein active?

In normal flies the amount of protein peaks in the early night, then drops to almost nothing during the day. Knowing this normal rhythm allowed Konopka and Benzer to make sense of the mutants. In the early hatchers, the protein levels peaked early. In the late hatchers, they peaked late. And what about the proteins in the flies with no rhythm? No working protein. The activity of the protein matched exactly what you would expect from one that was behind the daily rhythm.

By now a number of other labs were digging into the problem. Using powerful technologies of fly genetics, they isolated the DNA and found a number of other genes that work in this system. With each new gene, a finer understanding of the fly’s biological clock emerged.

A clock, even the biological one that Konopka and Benzer found, works something like a pendulum that swings back and forth at a set pace. The regular movement provides a basis to measure units of time. Looking at the clocks inside bodies means seeing molecular equivalents of pendulums inside cells. Here, the major timekeepers come about from chemical chain reactions in which each step occurs at a rate set by the laws of physics and chemistry. When DNA is activated, it makes interacting proteins that are transported through the cell and perform a number of tasks, one of which is to activate portions of DNA again, letting the cycle begin anew. This pendulum-like swing of chemical changes is defined by how fast proteins are made, combine, travel through the cell, and ultimately interact with DNA.

Mutant flies opened up not only a way to see genes that control biological clocks but also a new way to think about people.

About ten years after Konopka and Benzer’s discovery, a graduate student, Martin Ralph, was setting off to see if there were genes in mammals that controlled body clocks. He and his adviser in Oregon were working with Syrian hamsters, running them on treadmills to monitor their activity. Normal hamsters had rest and activity times, measured by how long they ran on a treadmill, that totaled to about twenty-four hours.

When each new shipment of hamsters came to the lab, Ralph would run them on his treadmills, hoping for some oddball pattern of rest and activity to emerge. He was making a huge bet that a mutant would randomly show up in one of his weekly shipments.

One day Ralph took the newly received batch of hamsters, put them in the cages, and let them run. To his joy—and relief, no doubt—one individual had a total daily rest and activity cycle that was dramatically different from twenty-four hours. This one hamster functioned on a twenty-two-hour cycle. When he bred the hamster with others, he found the offspring also had the shorter daily rhythm of rest and activity. The aberrant clock of this hamster was caused by a mutant gene.

When Ralph and others looked in more detail at the activity of the gene, they saw that the major effect of the mutant was a little patch of cells inside the brain. The mutation affected cells inside Richter’s patch. Ralph’s bet had paid off.

The plot thickened in the early 1990s when a patient entered a sleep clinic in Salt Lake City complaining of an odd problem. She got a regular eight hours of sleep each night. But no matter how hard she tried to stay awake, she always fell asleep at 7:30 p.m. With a normal eight hours of sleep, that meant she was waking at 3:30 a.m. Her clock ticked at a normal pace, only everything was shifted. Sound familiar?

Entering a sleep clinic means being probed, outfitted with patches, and connected to machines as you try to slumber, all in an effort to put some numbers on bodily functions—breathing, heart rate, body temperature, and so on—during the night. Every test showed that there was nothing strange about this woman’s health or behavior.

Shortly after the testing began, the patient revealed the critical fact that other family members shared the same sleeping timetable. There were several puzzles to the family’s sleeping habits. Other members of her family rose very early, but they lived in different places. One fact after another led the researchers to suspect that the cause didn’t lie in their homes, diets, or local environments.

The researchers assembled a full pedigree, mapping the family tree against which relatives rose early and which did not. Then the pattern emerged: here was a classic genetic trait, just like the fly mutants.

Looking at a family tree doesn’t reveal the actual change to DNA itself. That level of understanding requires taking cells from the body, by swabbing the cheek of each family member, and comparing the DNA inside the cells between those who rise early and those who wake at more normal hours. If there is a genetic difference, it should be seen in some part of the DNA that consistently varies between the risers.

Isolating the DNA of the early risers and comparing it with that of the normal sleepers showed that the altered sleeping pattern was caused by a very precise change to one gene. Genes and proteins leave their fingerprints everywhere. Once you know the sequence and structure of a gene or protein, it is a relatively simple matter to search for them in other cells. This trail led from the DNA of mutant human early risers, to that of Martin Ralph’s early running Syrian hamsters, ultimately to the gene that caused Konopka and Benzer’s flies to hatch early. Each species has its own specialized protein interactions inside the clock, but the basic genes and principles that drive the molecular pendulum are all there. Flies, hamsters, and people share parts of their clocks, their genes, and their histories.

Similar clock DNA not only leads us to our deep connection to other species but also reveals a fundamental machine inside the cells of our body. The same kind of genetic clock is within each of them, from Richter’s patch and the skin at the tip of your finger to those of the liver and brain. If you have a sleep disorder that has a genetic basis, the doctor can diagnose it from a scratch of skin, drop of blood, or swab of your cheek. Every cell ticks a daily rhythm with a molecular clock that has parts at least as ancient as animals themselves.

What sets the molecular clock inside our cells and aligns it to our days? A travel alarm clock might keep a twenty-four-hour rhythm, but it has no way of knowing what time zone it is in; it needs something to set it to where it is on the planet. Why do we experience jet lag or, in my case, rise at 2:00 a.m. in the Arctic summer?

Our cellular clock is tuned to the outside world by a number of triggers, the most important of which is light. Most of the light that enters our eyes ends up as a signal to the parts of our brain that interpret visual information. Some of these signals, though, get sent to a different part of the brain—to Richter’s patch of cells. The path from Richter’s patch travels to a little pea-sized gland at the base of your brain called the pineal. To some, including the great French philosopher René Descartes, the pineal is the seat of the soul. In some lizards and fish it actually forms a kind of third eye that records light information directly. In us, it is like a relay center for information. It emits the molecule melatonin, which triggers responses all over the body.

This reaction—from light to brain to the pineal gland to melatonin and its targets across the body—tunes our bodies to the light of the day and the darkness of night. When we travel to a different time zone, this pathway eventually resets us to a new regime of light and dark.

Shine bright light on somebody’s eyes in the middle of the day and what happens? Usually nothing at all beyond the usual adjustments of his or her visual apparatus. Shine bright light in people’s eyes at dusk, and you can affect sleep. People hit with light at dusk tend to become tired later than normal. The opposite is also often true: shine bright light on people at dawn, and their sleep cycle will be shifted earlier than normal. Our sleep cycle is dependent on light shined on us when our brains expect it to be dark. In a world of gadgets that blare artificial light into our eyes at all hours of the day, we are resetting our clocks with each text or e-mail sent in the middle of the night. We live in an age of disconnect between the ancient rhythms inside us and our modern life.

Much of our health depends on clocks: shift workers who sleep during the day and work at night have higher rates of heart disease and some cancers, notably of the breast. Researchers studying mice discovered that the error-correction machinery of the DNA of skin cells functions on a clock: it’s most active in the evening. The DNA that gets copied in the morning is likely to carry the most errors. The UV radiation of the sun causes cancers in the skin when it induces errors in copying DNA. Putting these facts together leads to the conclusion that in mice UV light hitting the skin in the morning is more carcinogenic than evening and afternoon exposure. Humans also have these clocks, but ours are reversed relative to mice: our DNA error-correction apparatus is most active in the morning. This means tanning at the end of the day is more carcinogenic than doing so in the morning. Even our metabolism is affected by the clocks inside our cells: some kinds of obesity can be correlated to a lack of sleep.

Given that mechanisms of DNA function and cell division are dependent on internal clocks, it should come as no surprise that a number of medicines are most effective at certain times of the day, when our brain anticipates the level of light. Our susceptibility to disease, and our treatment of it, carries the deep signal of a planetary cataclysm that happened over 4.5 billion years ago.

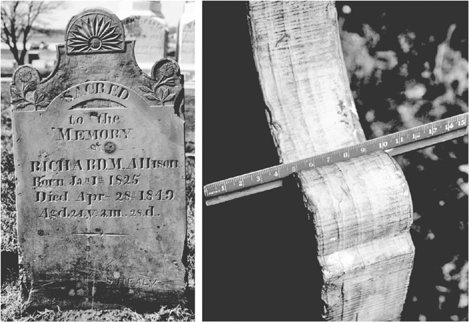

Dotting the landscape of southern Indiana are cemeteries that house the graves of Europeans who settled in the region in the late eighteenth century. This was a hearty crowd whose harsh existence is recorded on their tombstones. Few lived past the age of forty, and judging by the carved dates, the cemeteries were busy places some years. By an accident of geography, these settlers found a near-perfect material for their headstones. The fine grains and hardness of each stone preserve etchings from the early nineteenth century as sharply today as when they were originally carved.

We are so accustomed to looking at the front of tombstones that it is easy to overlook other edges that have stories to tell. The sides of the pioneers’ grave markers are not even; they are composed of a series of ridges with sharp edges and small depressions. The stones were quarried from a pit near Hindostan, Indiana, from an exposure that reveals how the rock was formed. Hundreds of millions of years ago, this part of Indiana lay under the sea. Year after year, sediment settled from the tidal waters, leaving small ripples in the mud. There is a rhythm to these marks, recording the variations of the tides throughout the year. As Earth spun and the moon circled it, the water rose and fell, only to be recorded as ridges in the sediment. The sides of the grave markers reveal the tidal rhythm from a moment when Earth rotated faster and the days were shorter than today. Time is sculpted everywhere on these tombstones, by the work of man and of the planet. The bodies in the graves and the rocks that mark them are united by the history they share with colliding and rotating celestial spheres.