Arctic bush pilots are a special breed. Years of solo flying endow them with a crusty independence and deep familiarity with the landscape. After countless hours looking down on terrain, pilots’ eyes can discern patterns hidden from the rest of us. During one flight in 2002, our pilot suddenly pushed the plane into a steep dive and veered into a tight bank, a maneuver that dropped us from ten thousand feet to about two hundred over the water in a small fjord. While I was seeing my life flash before my eyes, he saw a school of fish and, being a fisherman in his spare time, wanted to get a closer view. Even if my eyes weren’t closed, there was no way I could have perceived swimming arctic char from such an altitude.

During one chopper run in 1985, a pilot named Paul Tudge was shuttling supplies between distant camps on Canada’s Axel Heiberg Island and Eureka Sound, two of the North’s most spectacular places. When the air is clear and the ground free from snow, the colors and images are so sharp that tiny details can be visible miles in the distance. In this part of the Arctic, barren mountain ranges border gentle valleys. The enduring action of ice, wind, and intense cold sculpts the bedrock into a range of obelisks, sheer walls, and potholes that almost seem unnatural. The sensation of otherworldliness is magnified by the lack of large plants: there are no standing trees, shrubs, or even grass in this area.

Scanning brown, gray, and red vistas below his chopper, Tudge noticed something odd on the bedrock floor. Wind had winnowed a depression, out of which poked objects that looked like tree stumps. Not believing that there are trees in the Arctic, let alone ones that grew out of rock, Tudge set the chopper down. Lying in wait for him were not only tree stumps but piles of branches, logs, and other tree parts jutting from the ground. He dutifully collected samples and shipped them to one of the Arctic’s leading fossil plant experts, James Basinger of the University of Saskatchewan. Basinger dropped everything and mounted an expedition as soon as money and permits could allow; of course, in the Arctic this process can take a year or more.

Awaiting Basinger’s spade was an entire buried forest mummified in eroding rock. The cold dry air left fine anatomical details of the leaves and wood intact, including their original cellular structure. The wood of these trees even burns. There is a big difference between these logs and a Duraflame; the Arctic ones come from a forest over 40 million years old.

The stumps that jut from this frozen landscape expose redwood trees that would have reached heights of 150 feet or more. In the past, this place was no barren wasteland; it was alive with plants much like Northern California is today. Of course, nowadays the tallest tree up north is a little willow that rises mere inches off the ground. It is almost as difficult to see Arctic willows from six feet as Tudge’s fossil forest from the air.

About twenty years before Paul Tudge’s flight, the eminent paleontologist Edwin Colbert received a box in his office at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Sent by a famed geologist from the Ohio State University, it contained a sheet of official letterhead wrapped around an isolated bone the size of a human finger. The colleague had collected this fragment in the field and wanted Colbert’s expert opinion.

From his many years on expedition to the American Southwest, Colbert was able to identify the bone in a split second: it had the distinctive texture and shape of a jaw from an ancient amphibian that lived over 200 million years ago. Looking somewhat like fat crocodiles, these creatures were widespread throughout the globe for a good chunk of geological time. But this ordinary-looking fragment was very special: it came from the Transantarctic Mountains, a range two hundred miles from the South Pole.

Colbert was a longtime fossil hunter, and the sirens went off in his head. Opportunity knocked; here was a continent completely unexplored for fossils. Colbert wasted no time assembling a dream team of experts from the United States and South Africa, who from years of working on the rocks of this age had the eyes to find new fossils. If fossil bones were present in Antarctica, this was the team to find them.

Almost from the moment their boots touched the Antarctic sandstones, Colbert and his team had a field day picking bones from the sides of barren hills, where fossils were virtually everywhere they looked. One creature had a body shaped like a medium-sized dog, only instead of a jaw like a carnivore it had a large birdlike beak. What stopped Colbert in his tracks was not this creature’s bizarrely chimeric form but something far more mundane: paleontologists had known of this creature for decades. In the 1930s, South African geologists identified an entire layer that contains thousands of them extending across a wide swath of the Karoo Desert. This so-called Lystrosaurus Zone even reaches South America, India, and Australia. Now, with a Lystrosaurus level in Antarctica, Colbert and his colleagues uncovered yet another clue exposing the reality of continental drift. With the match of the rocks, coastlines, and fossils, a new view of Antarctica emerged: the continent in the past sat as a keystone at the center of a vast supercontinent that included Africa, Australia, and India. This clump of continents covered much of the southern part of the planet.

The pile of fossils that Colbert’s group discovered revealed another fact of Antarctica’s past. Lystrosaurus, like the amphibian that led him there in the first place, was a cold-blooded animal that could live only in warm tropical or subtropical climates; think big salamanders or lizards. Ditto the fossil plants. Colbert and his team labored near the center of a vast frozen continent, close to where Robert Falcon Scott and his party froze to death nearly sixty years before. But everything inside the rocks pointed to one conclusion: Antarctica was once a warm and wet world teeming with tropical life.

Expeditions that followed Colbert’s only exposed more of Antarctica’s disconnect between its frozen desolate present and its lush past. The world that Colbert uncovered was followed by another filled with dinosaurs and their kin. In rocks even more recent, 40 million years old, this tropical continent was home to modern rain forests, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and a whole menagerie of mammals. For most of its history, Antarctica was a paradise for life.

Then, starting 40 million years ago, the entire continent went into the freezer, and with it Antarctica witnessed the greatest and most complete extinction of any continent in the history of the planet. From a world rich in plants and animals, virtually every land-living creature simply disappeared.

There is symmetry to Tudge’s flight near the North Pole and Colbert’s exploration of the South: one unveiled temperate forests, the other tropical animals in regions that today house frozen deserts. The story of the poles is that of the entire planet. Our present—with its polar ice—is an aberration. For most of history our planet was warm, almost tropical. If the rocks of the world are a lens, they reveal that our modern, relatively cold landscape is not the normal state of affairs for the planet.

In this great cooling lies one of the major events that shaped our bodies, our world, and our ability to see all.

Carl Sagan once spoke of a paradox about our planet’s climate. The sun is not a constant beacon of light; it started its stellar life as a relatively dim star over 4.6 billion years ago and has increased in brightness ever since, being about 30 percent brighter and warmer now than when it formed. With such a dramatic increase in heat over the years, Earth should have been a frozen waste in the past and now be a roiling cauldron of molten crust. Yet all our thermometers for the planet paint a different picture. Glaciers exist today during an era when the temperatures should be downright hellish. There are signs of liquid water inside 3-billion-year-old rocks—at a time when Earth should have been a ball of ice. Sure, we’ve had our moments of hot and cold, but if you think about Venus’s surface temperatures of 900 degrees Fahrenheit and Mars’s of -81 degrees, Earth has been a stable Eden relative to its celestial neighbors. Somewhere on the planet lies a thermostat that buffers it from dramatic extremes in temperature.

Inroads to the thermostat were discovered by a student who was as persistent as he was headstrong. He started his graduate career by loudly proclaiming to his thesis adviser that he had a brand-new theory of electrical conductivity. The response to this arrogant introduction was a simple “good-bye.” Perseverance paid off, and, probably to the relief of his teachers, in 1881 Svante Arrhenius moved to Stockholm to work with a professor at the Academy of Sciences there. After that gig, Arrhenius went on to think of other scientific problems.

One scientific puzzle was right in front of Arrhenius’s eyes. He saw the factories of the Industrial Revolution belching coal smoke—in his words, “evaporating our coal mines into the air.” Arrhenius knew from previous work that carbon dioxide, a major constituent of the fumes, could capture heat. He made a few calculations that revealed how increased carbon dioxide in the air would trap heat on Earth and raise global temperatures. This idea was to lay fallow for a number of years, during which time Arrhenius won the Nobel Prize for work derived from the seemingly lackluster doctoral thesis that had so annoyed his professors.

The famous greenhouse effect is based on Arrhenius’s work. The more carbon dioxide there is in the atmosphere, the more heat is trapped by the planet and the hotter things get. Of course the reverse is true. But there is a deeper meaning to carbon in the air, one that emerges only when you take the long view on timescales that extend millions of years in the past.

The television character Archie Bunker once famously said of beer, “You don’t own it, you rent it.” The same holds true for every atom inside us; we are the temporary holders of the materials that compose our bodies. Few of these constituents are more important to the balance of life and the planet than carbon. The connection among parts of Earth depends on how carbon moves through air, rock, water, and bodies. To see this chain of connections, we need to consider living things, rocks, and oceans not as entities in their own right but as stopping places for carbon as it marches along during our planet’s evolution.

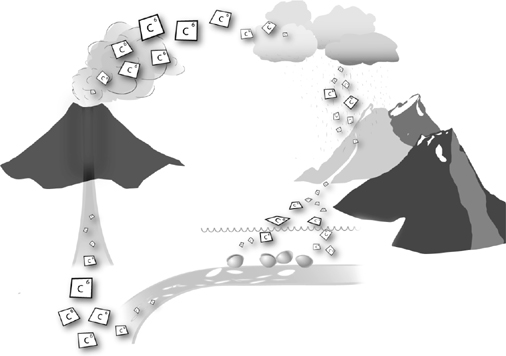

Viewed in this way, the amount of carbon in the air depends on a delicate balance of conditions. Carbon in the atmosphere mixes with water and rains down to the surface as a slightly acidic precipitation. We see the effects of this in our daily lives; in my university, built largely in the late nineteenth century, few gargoyles still have faces. Acid rain works on exposed rock everywhere—on mountainsides, rubble fields, and sea cliffs. Once the acid rain breaks down rocks, the water—now also enriched with carbon that was inside the rocks—eventually winds its way through streams and rivers into the oceans. At this point the carbon gets incorporated into the bodies and cells of the creatures that swim there: seashells, fish, and plankton. When sea creatures’ remains, loaded with carbon, settle to the bottom of the ocean, they ultimately become part of the seafloor. And, as we’ve known since Marie Tharp, Bruce Heezen, and Harry Hess, the seafloor moves, only to be recycled deep inside Earth.

This chain of events removes carbon from the atmosphere, taking it from the air and moving it to the hot internal crust of Earth. Alone, these steps would pull all the carbon out of the air, leaving Earth freezing with no atmospheric insulation. The good news is that there is a recycling mechanism for carbon. Carbon in the interior of Earth gets injected back into the atmosphere by volcanoes that eject gases. That is the long-term source of much of the carbon we breathe: while acid rain and the weathering of rocks remove carbon from the air, volcanoes emitting gases return it. Volcanoes typically release huge amounts of water vapor, carbon dioxide, and other gases; by some estimates they send over 120 million tons of carbon dioxide into the air each year.

Like a sequence of events in which each step makes sense but the end points are counterintuitive, the conclusion to draw from carbon’s movement is that rock erosion and weathering is linked to climate. Rock erosion by acid rain is like a giant sponge that pulls carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Lowering the amount of carbon dioxide in the air will drop the planet’s temperature. On the other hand, planetary events that increase the amount of carbon in the air—enhancing volcanic activity or slowing removal of carbon from the air—will, of course, serve to raise temperatures. All else being equal, increasing erosion of rocks leads to lower temperatures, decreasing erosion to higher ones.

The movement of carbon links rocks to climate and ultimately answers Sagan’s paradox about the sun. The planet’s temperatures are kept within a narrow range by the movement of carbon molecules through air, rain, rock, and volcano. Hot weather leads to more rock erosion, which leads to more carbon being pulled out of the air and thus colder weather. Then, just as things get colder, the cycle moves the planet’s temperatures in the opposite direction: colder weather leads to less erosion, increasing amounts of carbon in the air, and hotter temperatures. Liquid water is possible on our planet only because of this balance; neither we nor the landscapes we depend on could exist without it. But liquid water is like the miner’s canary. Too much of it, or too little, reveals a long-term shift in workings of the planet, changes that amount to planetary fevers and chills.

What happened when the poles started to freeze about 40 million years ago? The shift from hot to cold occurred at the same time that the levels of carbon in the atmosphere dropped precipitously. But this begs the question: What changed the levels of carbon in the air?

Maureen “Mo” Raymo went to school to study climate and the kinds of geological changes that could have an impact on it. And, like Arrhenius, she produced a thesis that elicited memorable comments from advisers. One went so far as to comment that her Ph.D. dissertation was “a total crock.”

Her path to that fine moment began like any other graduate student’s: she took a string of classes representing the core knowledge of her field. In geology seminars of the 1980s, much of the buzz was about global carbon and Earth’s thermostat. A classic paper, read by every student at the time, written by Robert Berner, Antonio Lasaga, and Robert Garrels, described this link in chemical detail. The paper became affectionately known as BLaG after the initials in the last names of each author. Everybody read BLaG and everybody was tested on BLaG, even though virtually everybody, including the BLaG authors themselves, realized key details of their brilliant model had yet to be filled out.

Raymo took the standard class for graduate students where the details of BLaG were presented. She also took classes on modern rivers, mountain formation, and tectonics. But unlike the rest of us who sat through this kind of curriculum, she began to connect the dots.

Everybody knew that the climate cooled drastically starting 40 million years ago, but there was no known geological mechanism that could possibly have done this. What could drop the temperatures? Only a major planetary change could possibly have removed enough carbon to allow such cooling.

Then Raymo looked at a globe and remembered her plate tectonics. The period of drastic cooling commenced at a pivotal time in the history of the planet. This was when the continental plate of India, which had been traveling north for hundreds of millions of years, began to slam into Asia. The result of this collision is like sliding two stacks of paper along a tabletop until they scrunch together: they crinkle and rise. A similar kind of mashup of the continents led to the rise of the Tibetan Plateau and the Himalaya mountains.

Raymo’s lead adviser (not the one who called her thesis a crock) was thinking about how a new mountain range would affect global wind currents or serve to make a shadow that could foster storms. Raymo’s insight came from thinking about how a massive mountain range and plateau could affect Earth’s thermostat.

The Tibetan Plateau is a vast barren face of virtually naked rock. It contains over 82 percent of the rock surface area of the planet and reaches over twelve thousand feet high. With the rise of such a plateau came ever growing amounts of rock erosion on its surface. When we look at the Himalayas, most of us see a dramatic series of mountains, but Raymo saw a giant vacuum that removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere—and rivers that flush the carbon into the sea. With decreasing carbon in the atmosphere came a cooler planet. The rise of the Tibetan Plateau led to the shift from a warm Earth to a cold one; it did so by pulling carbon from the air via erosion of rock.

Raymo’s theory makes sense of an enormous amount of data, but gaining support for an idea like this is more like winning a criminal case on circumstantial evidence than it is a mathematical proof; only the agreement of a heap of independent lines of evidence can nail the case. Raymo made a very specific prediction: the test lies in using tools that can correlate measurements of the rates of uplift of the plateau—and the levels of weathering of rock—with the amount of carbon in the air. There are altimeters in ancient rocks—altitude-sensitive plants. Carbon in the air dropped at the time of uplift, but we still do not have the precision to tie the different variables together in the fine detail needed for a test. Whether erosion of the plateau alone is sufficient for the climate change we see or if this acted in concert with other mechanisms remains to be seen.

By 40 million years ago, the map of the world was on the move, and with it the environment that supports life. India slamming into Asia may have heralded an era of dropping levels of carbon dioxide and global cooling, but details of the timing of the freezing of Antarctica suggest other contributing factors. Forty million years ago, it went from being a rain forest to having a climate much like southern Patagonia today. Then, by about 30 million years ago, the fauna and flora started to diminish, until 20 million years ago, when the first permanent sea ice appeared. The vegetation was largely that of stunted tundra by this time. Ten million years ago desolation was complete.

Look at a map, and you’ll notice that the Northern Hemisphere is mostly brown land and the Southern Hemisphere is mostly blue ocean: the northern half of Earth is composed of large and mostly connected continents, and the southern one, vast oceans. Inside this simple observation lie clues to the freezing of the planet, the vanquishing of life on Antarctica, and the environmental changes behind much of human history.

By the early 1970s, as the reality of plate tectonics was being widely acknowledged, one huge patch of ocean floor remained virtually unexplored: the waters of the southern oceans made famous by the great explorers of Antarctica such as Robert Falcon Scott, Ernest Shackleton, and Roald Amundsen. Rough seas separate icebergs and barren rocky islands, so much so that the latitudes from 40 degrees to 70 degrees in which this southern ocean sits are given nicknames: the “roaring 40s, furious 50s, and shrieking 60s.” This was among the last regions of the ocean floor to be sampled for a good reason. The ocean currents and winds make for a forbidding sea.

Coming off their successes mapping the floors of the Atlantic and the Pacific, the ocean-mapping teams that supported the work of people like Heezen and Tharp turned to this southern patch. From 1972 to 1976, expeditions were sent to core about twenty-six sites to look at the sediments of the ocean bottom. At each stop in the ocean, at a site determined by studying maps at home, a winch returned a plug of seafloor captured from a core at the bottom. Each rock was studied chemically to reveal its age and origins, and the structure of the ocean bottom was mapped just as Marie Tharp and Bruce Heezen had done a decade before in the Atlantic.

The cores from the sea bottom changed the way we look at the southern world. Surrounding Antarctica like a ring is a huge rift valley with a molten core. This, like the rift at the bottom of the Atlantic, is a place where new seafloor is being made, where the plate is actually spreading. The jigsaw puzzle of the South, contained in the shape of the continents and Colbert’s Lystrosaurus discovery, became clear. At one time in the past, the entire southern part of the globe was indeed one giant super landmass composed of what are today all the southern continents: Antarctica, Australia, South America, and Africa. The distinctive blue oceans that define our South today weren’t there.

Then, with the birth of this volcanic ring surrounding Antarctica, the continents separated and moved away from their southern neighbor. Three things happened at once: Africa, Australia, and South America moved north, Antarctica became isolated at the South Pole, and vast seas opened up separating all the southern continents. None of these changes boded well for life near the South Pole.

Just as isolation is bad for people, so too is it for polar continents. The ocean current that has so vexed mariners for years runs as a ring around Antarctica from east to west. It was born as space was created for it by continents cleaving from Antarctica. Oceans are wonderful ways to transport heat. As an example, Britain lies at the same latitude as northern Labrador. One place is relatively mild, the other quite fiercely cold. The reason? Warm currents coming up from the equator keep Britain’s climate mild, whereas the western Atlantic has no such current. Before Antarctica became isolated, ocean currents running from the equator brought heat to the continent. When Antarctica separated from the other southern continents, this conveyor of heat stopped, only to be replaced by the ring current. This change spelled cold for Antarctica: whatever heat existed at the South Pole just escaped into the air, never to be replenished by warm waters. Life on Antarctica literally froze to death or skedaddled to greener pastures elsewhere.

The emerging map of the world changed climate and life. Moving continents and expanding seafloor brought new patterns of ocean circulation, erosion, and levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, thereby dooming an entire continent. The consequences extend as far as the eye can see.

Humans are visual animals built to detect patterns in a messy world. Bush pilots’ eyes, like those of Paul Tudge, are trained to spot objects on a flight. Children can find hidden objects in puzzles or pictures, fly fishermen learn the water by seeing shadows below the ripples in streams, and radiologists save lives by deciphering shadows on images: our species has survived by finding patterns hidden in the apparent chaos around us. This ability lies in the interplay between our eyes and our brains: together they help us learn to see, survive, and thrive.

We live in a world so awash in vivid hues that it is easy to forget we perceive only a tiny fraction of the colors in front of our eyes. Light arrives to us in a wide spectrum of wavelengths, from ultraviolet to infrared. Gadgets such as night-vision goggles provide only a glimmer of these hidden frequencies. Other creatures can see a broader range of colors naturally. Birds perceive many more shades of blue, as do some species of fish. Each species—whether eagle, trout, or human—is tuned to experience and perceive its world in a particular way. And our perception has its roots in the forces that froze the poles of Earth.

Human eyes, like those of other mammals, have a postage-stamp-sized retina in the back that receives light from the lens. Plastered on the retina are about 5 million specialized cells that are like little receivers to detect red, yellow, and blue—the three primary colors of light. This ability is conferred on each cell by a specialized protein inside that undergoes a distinctive change in shape when the right color hits it. The cells in the retina can discriminate about a hundred different shades of light. When these signals hit the brain, they are combined, allowing us to perceive a palette of about 2.3 million different colors.

Our closest primate cousins of the Old World—monkeys, gorillas, chimps, and orangutans—can see the same palette of colors as we do. We share a very similar makeup, which extends to the proteins inside the retina we use to perceive color. More distantly related primates, such as those that live in South America, do not see in color exclusively: in some species the males are color-blind. Ever since the nineteenth century, primatologists have known about a big split in our primate family tree: all Old World monkeys have full color vision, whereas this trait is lacking in their New World cousins. Is there also a difference in lifestyle that explains the ability to see in vivid color?

The first hint came from a surprising finding. Howler monkeys, as the name implies, have a distinctive cry. They were described by the great explorer Alexander von Humboldt in the nineteenth century as having “eyes, voice, and gait indicative of melancholy.” Scientists studying their behaviors and visual structures in the 1990s discovered that unlike South American monkeys, all howlers are able to see in the same spectrum of color as we do. There is a huge difference in the diets of howlers and their South American cousins. All other monkeys eat mostly fruit, whereas howlers exist on leaves.

This observation motivated a young graduate student, Nathaniel Dominy, a former football player at the Johns Hopkins University, to think in a new way about how color vision arose. Perhaps the lessons of the howlers is general, he thought, and there is a major difference in diet that explains why our branch of the primate family tree sees in color.

Kibale National Park in western Uganda sits among a rich forest landscape of evergreen and mixed deciduous trees. Leopards, hornbills, and distinctive forest elephants—unusually hairy and small—dwell there. So too does an astounding di-versity of primates. A whopping thirteen species—including chimpanzees—make the park their home.

Kibale is also home to a fourteenth species of primate—humans—many of whom live in the Makerere University Biological Field Station to study their primate cousins. In 1999, Dominy traveled there with the simple goal of watching the monkeys eat.

Dominy and his research adviser, Peter Lucas, had a plan: they were going to look at each type of primate in the reserve and quantify exactly what it ate and when. If there was a pattern to the diets, they were going to find it. The crew wasn’t just armed with notepads; they carried a backpack laboratory that was described in a later scientific paper with a title that says it all: “Field Kit to Characterize Physical, Chemical, and Spatial Aspects of Potential Primate Foods.” Inside the backpack was a materials testing device designed to measure toughness of foods; a spectrometer to quantify color and basic nutritional properties of foods; and a number of other gizmos to record the shape and weight of whatever the monkeys gobbled up.

Dominy, Lucas, and their team spent ten months watching primates. When they weren’t interrupted by the threat of bandits or terrorists (at one point they were forced to retreat to the American embassy in Uganda), they worked around the clock, eventually logging 1,170 hours of observations. They would watch the animal as it consumed its meal, then hit the leftovers with their backpack lab. In the end, they found that the monkeys consumed about 118 different kinds of plants.

Back home, as they crunched the data, a pattern emerged. Species with color vision preferentially selected leaves that varied on the red-green color scale. That is, they were differentiating foods that animals lacking color vision could never even perceive. And what of the foods that they selected using their color vision? These morsels uniformly had the highest amount of protein for the least amount of toughness. The primates’ mothers must have been pleased: they ate things that were both good for them and easy to digest. And the biggest cue, red color, was something that only species with full color vision could detect.

To Dominy and his colleagues, a hypothesis emerged: color vision enabled creatures to discriminate among different kinds of leaves and locate the most nutritious ones. This advantage gained new prominence when climates changed and plants responded.

More clues to color vision are nestled inside DNA. Mammals that lack color vision have only two proteins to perceive color; we and the Old World apes that perceive colors have three. In 1999, as DNA technology became cheaper and more powerful, the actual composition of these proteins could be compared, giving a detailed look at their chemical structure. Hidden inside the sequences was a major clue to the origin of color vision. The three proteins that allow us to see colors are duplicates of the two seen in other mammals. By comparing the sequences in the new copies with the old ones, we can get an estimate of when the duplication happened. All creatures with the three genes trace their lineage back to about 40 to 30 million years ago, the likely time when color vision arose in our closest ape ancestors.

What happened to the planet at the time of this genetic change? Earth got cooler. The forests of Antarctica and the North retreated, to be replaced by ice. Grasses spread to new places around the world. The fruit-bearing palm and fig trees, so common in Wyoming and throughout the warm world, declined, yielding forests mostly of leaves—some tough, some soft, some nutritious, some inedible. The skills that are now so useful to the primates with color vision in Kibale, Uganda, were a key to their success during the period of global cooling. The cold brought a new flora, one that put a new kind of color vision at a premium.

Paul Tudge discerned tiny stumps in a vast landscape, paleontologists find tiny fossils inside a field of rocks, and our primate ancestors survived climate change by discriminating nutritious foods in a dense collage of leaves in forests. Every time you admire a richly colorful view, you can thank India for slamming into Asia, continents for retreating from Antarctica, and the poles for becoming frozen wastes. Buried within it all lies the way carbon atoms move through our world.