FREE as a Business Model

Def_Pattern No. 4

FREE • In the FREE business model at least one substantial Customer Segment is able to continuously benefit from a free-of-charge offer. • Different patterns make the free offer possible. • Non-paying customers are financed by another part of the business model or by another Customer Segment.

[ REF·ER·ENCES ]

1 • “Free! Why $0.00 is the Future of Business.” Wired Magazine. Anderson, Chris. February 2008.

2 • “How about Free? The Price Point That Is Turning Industries on Their Heads.” Knowledge@Wharton. March 2009.

3 • Free: The Future of a Radical Price. Anderson, Chris. 2008.

[ EX·AM·PLES ]

Metro (free paper), Flickr, Open Source, Skype, Google, Free Mobile Phones

Receiving something free of charge has always been an attractive Value Proposition. Any marketer or economist will confirm that the demand generated at a price of zero is many times higher than the demand generated at one cent or any other price point. In recent years free offers have exploded, particularly over the Internet. The question, of course, is how can you systematically offer something for free and still earn substantial revenues? Part of the answer is that the cost of producing certain giveaways, such as online data storage capacity, has fallen dramatically. Yet to make a profit, an organization offering free products or services must still generate revenues somehow.

There are several patterns that make integrating free products and services into a business model possible. Some of the traditional FREE patterns are well known, such as advertising, which is based on the previously discussed pattern of multi-sided platforms (see Multi-Sided Platforms). Others, such as the so-called freemium model, which provides basic services free of charge and premium services for a fee, have become popular in step with the increasing digitization of goods and services offered via the Web.

Chris Anderson, whose Long Tail concept we discussed previously (see The Long Tail), has helped the concept of FREE gain widespread recognition. Anderson shows that the rise of new free-of-charge offers is closely related to the fundamentally different economics of digital products and services. For example, creating and recording a song costs an artist time and money, but the cost of digitally replicating and distributing the work over the Internet is close to zero. Hence, an artist can promote and deliver music to a global audience over the Web, as long as he or she finds other Revenue Streams, such as concerts and merchandising, to cover costs. Bands and artists who have experimented successfully with free music include Radiohead and Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails.

In this section we look at three different patterns that make FREE a viable business model option. Each has different underlying economics, but all share a common trait: at least one Customer Segment continuously benefits from the free-of-charge offer. The three patterns are (1) free offer based on multi-sided platforms (advertising-based), (2) free basic services with optional premium services (the so-called “freemium” model), (3) and the “bait & hook” model whereby a free or inexpensive initial offer lures customers into repeat purchases.

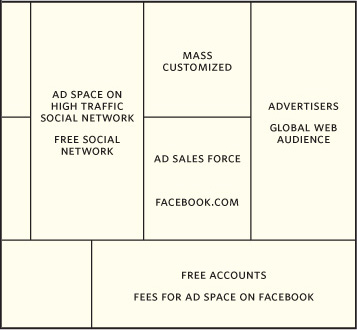

Advertising: A Multi-Sided Platform Model

Advertising is a well-established revenue source that enables free offers. We recognize it on television, radio, the Web, and in one of its most sophisticated forms, in targeted Google ads. In business model terms, FREE based on advertising is a particular form of the multi-sided platform pattern (see Multi-Sided Platforms). One side of the platform is designed to attract users with free content, products, or services. Another side of the platform generates revenue by selling space to advertisers.

One striking example of this pattern is Metro, the free newspaper that started in Stockholm and is now available in dozens of cities around the world. The genius of Metro lies in how it modified the traditional daily newspaper model. First, it offered the paper for free. Second, it focused on distributing in high-traffic commuter zones and public transport networks by hand and with self-service racks. This required Metro to develop its own distribution network, but enabled the company to quickly achieve broad circulation. Third, it cut editorial costs to produce a paper just good enough to entertain younger commuters during their short rides to and from work. Competitors using the same model soon followed, but Metro kept them at bay with a couple of smart moves. For example, it controlled many of the news racks at train and bus stations, forcing rivals to resort to costly hand distribution in important areas.

Metro

KA & C$ Minimizes costs by cutting editorial team to produce a daily paper just “good enough” for a commute read

VP, CH, CS & R$ Assures high circulation through free offer and by focusing on distributing in high-traffic commuter zones and public transport networks

Mass ≠ automatic ad $

A large number of users does not automatically translate into an El Dorado of advertising revenues, as the social networking service Facebook has demonstrated. The company claimed over 200 million active users as of May 2009, and said more than 100 million log on to its site daily. Those figures make Facebook the world’s largest social network. Yet users are less responsive to Facebook advertising than to traditional Web ads, according to industry experts. While advertising is only one of several potential Revenue Streams for Facebook, clearly a mass of users does not guarantee huge advertising revenues. At this writing, privately held Facebook did not disclose revenue data.

Newspapers: Free or Not Free?

One industry crumbling under the impact of FREE is newspaper publishing. Sandwiched between freely available Internet content and free newspapers, several traditional papers have already filed for bankruptcy. The U.S. news industry reached a tipping point in 2008 when the number of people obtaining news online for free outstripped those paying for newspapers or news magazines, according to a study by the Pew Research Center.

Traditionally, newspapers and magazines relied on revenues from three sources: newsstand sales, subscription fees, and advertising. The first two are rapidly declining and the third is not increasing quickly enough. Though many newspapers have increased online readership, they’ve failed to achieve correspondingly greater advertising revenues. Meanwhile, the high fixed costs that guarantee good journalism—news gathering and editorial teams—remained unchanged.

Several newspapers have experimented with paid online subscriptions, with mixed results. It is difficult to charge for articles when readers can view similar content for free on Web sites such as CNN.com or MSNBC.com. Few newspapers have succeeded in motivating readers to pay for access to premium content online.

On the print side, traditional newspapers are under attack from free publications such as Metro. Though Metro offers a completely different format and journalistic quality and focuses primarily on young readers who previously ignored newspapers, it is ratcheting up the pressure on fee-for-service news providers. Charging money for news is an increasingly difficult proposition.

Some news entrepreneurs are experimenting with novel formats focused on the online space. For example, news provider True/Slant (trueslant.com) aggregates on one site the work of over 60 journalists, each an expert in a specific field. The writers are paid a share of the advertising and sponsorship revenues generated by True/Slant. For a fee, advertisers can publish their own material in pages paralleling the news content.