Technique_No. 4

Prototyping

Summer, 2000

With a look bordering on panic, Weatherhead School of Management Professor Richard Boland Jr. watched as Matt Fineout, an architect with Gehry & Associates, casually tore up plans for a new school building . . .

. . . Boland and Fineout had been struggling for two full days to remove some 5,500 square feet from the floor plan designed by star architect Frank Gehry, while leaving room needed for meeting spaces and office equipment.

At the end of the marathon planning session, Boland had breathed a sigh of relief. “It’s finally done,” he thought. But at that very moment, Fineout rose from his chair, ripped the document apart, and tossed the scraps into a trash bin, not bothering to retain a single trace of the pair’s hard labor. He responded to Professor Boland’s shocked expression with a gentle shrug and a soft remark. “We’ve shown we can do it; now we need to think of how we want to do it.”

Looking back, Boland describes the incident as an extreme example of the relentless approach to inquiry he experienced while working with the Gehry group on the new Weatherhead building. During the design phase, Gehry and his team made hundreds of models with different materials and of varying sizes, simply to explore new directions. Boland explains that the goal of this prototyping activity was far more than the mere testing or proving of ideas. It was a methodology for exploring different possibilities until a truly good one emerged. He points out that prototyping, as practiced by the Gehry group, is a central part of an inquiry process that helps participants gain a better sense of what is missing in the initial understanding of a situation. This leads to completely new possibilities, among which the right one can be identified. For Professor Boland, the experience with Gehry & Associates was transformative. He now understands how design techniques, including prototyping, contribute to finding better solutions for the entire spectrum of business problems. Together with fellow professor Fred Collopy and other colleagues, Boland is now spearheading the concept of Manage by Designing: the integration of design thinking, skills, and experiences into Weatherhead’s MBA curriculum. Here, students use tools of design to sketch alternatives, follow through on problem situations, transcend traditional boundaries, and prototype ideas.

Prototyping’s Value

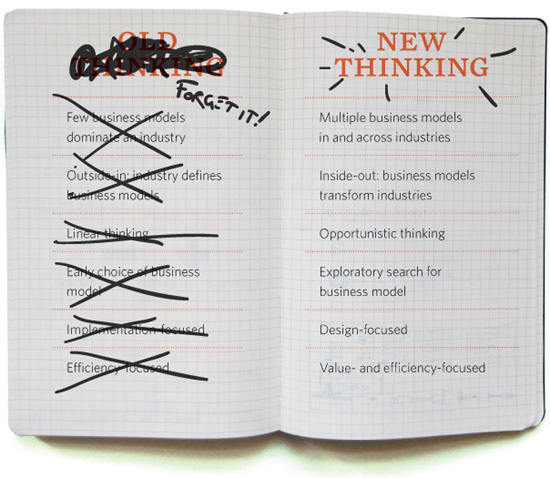

Prototyping is a powerful tool for developing new, innovative business models. Like visual thinking, it makes abstract concepts tangible and facilitates the exploration of new ideas. Prototyping comes from the design and engineering disciplines, where it is widely used for product design, architecture, and interaction design. It is less common in business management because of the less tangible nature of organizational behavior and strategy. While prototyping has long played a role at the intersection of business and design, for example in manufactured product design, in recent years it has gained traction in areas such as process design, service design, and even organization and strategy design. Here we show how prototyping can make an important contribution to business model design.

Although they use the same term, product designers, architects, and engineers all have different understandings of what constitutes a “prototype.“ We see prototypes representing potential future business models: as tools that serve the purpose of discussion, inquiry, or proof of concept. A business model prototype can take the form of a simple sketch, a fully thought-through concept described with the Business Model Canvas, or a spreadsheet that simulates the financial workings of a new business.

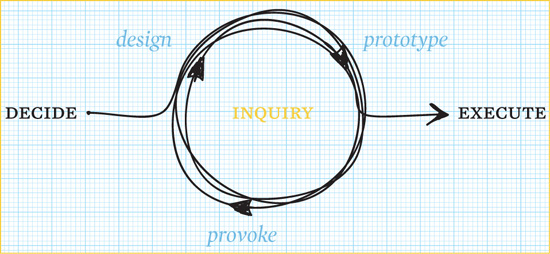

It is important to understand that a business model prototype is not necessarily a rough picture of what the actual business model will actually look like. Rather, a prototype is a thinking tool that helps us explore different directions in which we could take our business model. What does it mean for the model if we add another client segment? What are the consequences of removing a costly resource? What if we gave away something for free and replaced that Revenue Stream with something more innovative? Making and manipulating a business model prototype forces us to address issues of structure, relationship, and logic in ways unavailable through mere thought and discussion. To truly understand the pros and cons of different possibilities, and to further our inquiry, we need to construct multiple prototypes of our business model at different levels of refinement. Interaction with prototypes produces ideas far more readily than discussion. Prototype business models may be thought-provoking—even a bit crazy—and thus help push our thinking. When this happens, they become signposts pointing us in as-yet unimagined directions rather than serving as mere representations of to-be-implemented business models. “Inquiry” should signify a relentless search for the best solution. Only after deep inquiry can we effectively pick a prototype to refine and execute—after our design has matured.

Businesspeople are likely to display one of two reactions to this process of business model inquiry. Some might say, “Well, that is a nice idea, if we only had the time to explore different options.“ Others might say that a market research study would be an equally good way to come up with new business models. Both reactions are based on dangerous preconceptions.

The first supposes that “business as usual” or incremental improvements are sufficient to survive in today’s competitive environment. We believe this path leads to mediocrity. Businesses that fail to take the time to develop and prototype new, groundbreaking business model ideas risk being sidelined or overtaken by more dynamic competitors—or by insurgent challengers appearing, seemingly, from nowhere.

The second reaction assumes that data is the most important consideration when designing new strategic options. It is not. Market research is a single input in the long and laborious process of prototyping powerful new business models with the potential to outperform competitors or develop entirely new markets.

Where do you want to be? At the top of the game, because you’ve taken the time to prototype powerful new business models? Or on the sidelines, because you were too busy sustaining your existing model? We’re convinced that new, game-changing business models emerge from deep and relentless inquiry.

Design Attitude

“If you freeze an idea too quickly, you fall in love with it. If you refine it too quickly, you become attached to it and it becomes very hard to keep exploring, to keep looking for better. The crudeness of the early models in particular is very deliberate.”

Jim Glymph, Gehry Partners

As businesspeople, when we see a prototype we tend to focus on its physical form or its representation, viewing it as something that models, or encapsulates the essence of, what we eventually intend to do. We perceive a prototype as something that simply needs to be refined. In the design profession, prototypes do play a role in pre-implementation visualization and testing. But they also play another very important role: that of a tool of inquiry. In this sense they serve as thinking aids for exploring new possibilities. They help us develop a better understanding of what could be.

This same design attitude can be applied to business model innovation. By making a prototype of a business model we can explore particular aspects of an idea: novel Revenue Streams, for example. Participants learn about the elements of a prototype as they construct and discuss it. As previously discussed , business model prototypes vary in terms of scale and level of refinement. We believe it is important to think through a number of basic business model possibilities before developing a business case for a specific model. This spirit of inquiry is called design attitude, because it is so central to the design professions, as Professor Boland discovered. The attributes of design attitude include a willingness to explore crude ideas, rapidly discard them, then take the time to examine multiple possibilities before choosing to refine a few—and accepting uncertainty until a design direction matures. These things don’t come naturally to businesspeople, but they are requirements for generating new business models. Design attitude demands changing one’s orientation from making decisions to creating options from which to choose.

Prototypes at Different Scales

In architecture or product design, it is easy to understand what is meant by prototyping at different scales, because we are talking about physical artifacts. Architect Frank Gehry and product designer Philippe Starck construct countless prototypes during a project, ranging from sketches and rough models to elaborate, full-featured prototypes. We can apply the same scale and size variations when prototyping business models, but in a more conceptual way. A business model prototype can be anything from a rough sketch of an idea on a napkin to a detailed Business Model Canvas to a field-testable business model. You may wonder how all of this is any different from simply sketching out business ideas, something any businessperson or entrepreneur does. Why do we need to call it “prototyping”?

There are two answers. First, the mindset is different. Second, the Business Model Canvas provides structure to facilitate exploration.

Business model prototyping is about a mindset we call “design attitude.” It stands for an uncompromising commitment to discovering new and better business models by sketching out many prototypes —both rough and detailed—representing many strategic options. It’s not about outlining only ideas you really plan to implement. It’s about exploring new and perhaps absurd, even impossible ideas by adding and removing elements of each prototype. You can experiment with prototypes at different levels.

NAPKIN SKETCH

OUTLINE AND PITCH A ROUGH IDEA

DRAW A SIMPLE BUSINESS MODEL CANVAS. DESCRIBE THE IDEA USING ONLY KEY ELEMENTS.

• Outline the idea

• Include the Value Proposition

• Include the main Revenue Streams

ELABORATED CANVAS

EXPLORE WHAT IT WOULD TAKE TO MAKE THE IDEA WORK

DEVELOP A MORE ELABORATE CANVAS TO EXPLORE ALL THE ELEMENTS NEEDED TO MAKE THE BUSINESS MODEL WORK.

• Develop a full Canvas

• Think through your business logic

• Estimate the market potential

• Understand the relationships between Building Blocks

• Do some basic fact-checking

BUSINESS CASE

EXAMINE THE VIABILITY OF THE IDEA

TURN THE DETAILED CANVAS INTO A SPREADSHEET TO ESTIMATE YOUR MODEL’S EARNING POTENTIAL.

• Create a full Canvas

• Include key data

• Calculate costs and revenues

• Estimate profit potential

• Run financial scenarios based on different assumptions

FIELD-TEST

INVESTIGATE CUSTOMER ACCEPTANCE AND FEASIBILITY

YOU’VE DECIDED ON A POTENTIAL NEW BUSINESS MODEL, AND NOW WANT TO FIELD-TEST SOME ASPECTS.

• Prepare a well-justified business case for the new model

• Include prospective or actual customers in the field test

• Test the Value Proposition, Channels, pricing mechanism, and/or other elements in the marketplace

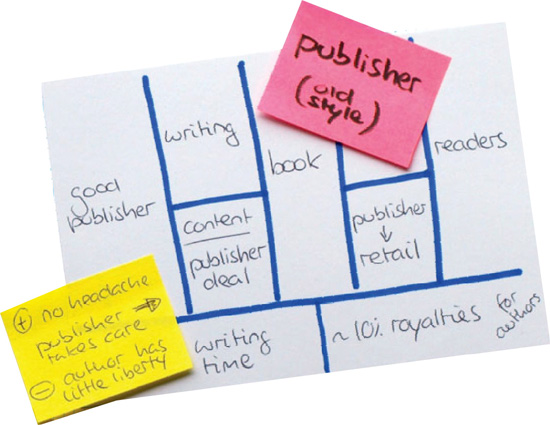

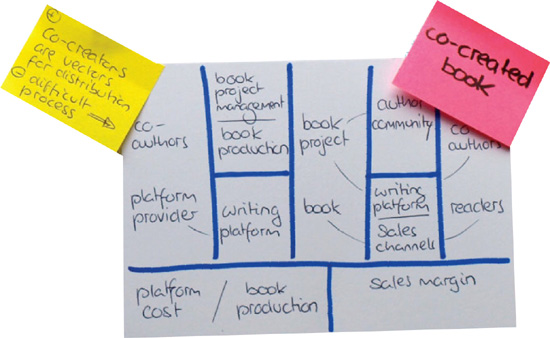

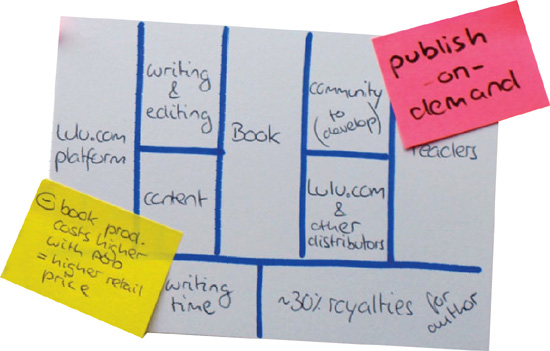

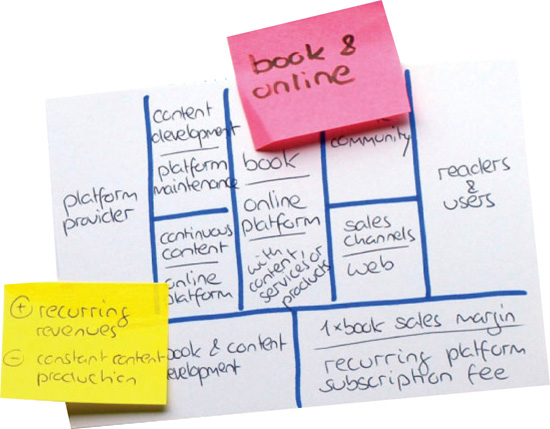

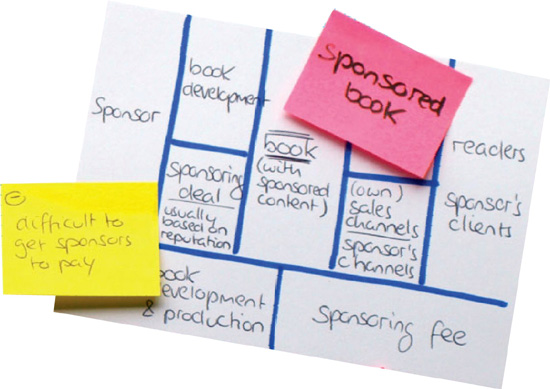

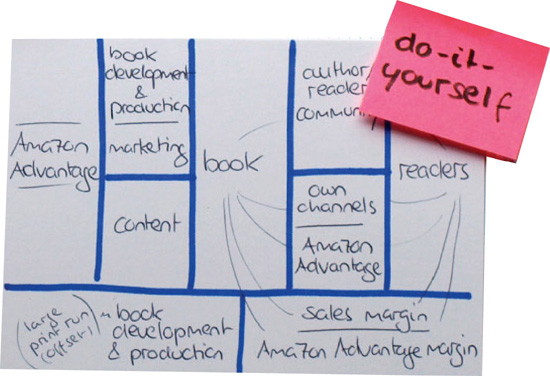

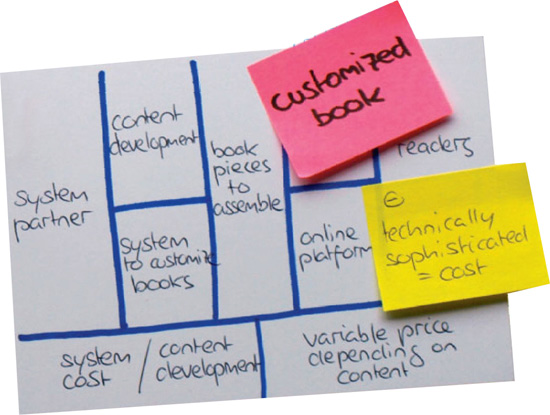

Eight Business Model Prototypes for Publishing a Book

Here are eight different business model prototypes outlining possible ways to publish a book. Each prototype highlights different elements of its model.

A prototype rarely describes all the elements of a “real” business model. It focuses instead on illuminating particular aspects of the model and thus indicating new directions for exploration.

Wanted: A New Consulting Business Model

John, 55 Founder & CEO Strategy Consultancy 210 employees

John Sutherland needs your help. John is the founder and CEO of a midsized global consulting firm that focuses on advising companies on strategy and organizational issues. He is looking for a fresh, outside perspective on his company because he believes that his business needs to be re-envisioned.

John built his company over two decades and now employs 210 people worldwide. The focus of his consultancy is helping executives develop effective strategies, improve their strategic management, and realign their organizations. He competes directly with McKinsey, Bain, and Roland Berger. One problem he faces is being smaller than his top-tier competitors, yet much larger than the typical niche-focused strategy consultancy. But John is not preoccupied with this issue, since his company is still doing reasonably well. What really troubles him is the strategic consulting profession’s poor reputation in the marketplace, and growing client perception that the prevalent hourly and project-based billing model is outdated. Though his own firm’s reputation remains good, he has heard from several clients that they think consultants overcharge, under-deliver, and show little genuine commitment to client projects.

Such comments alarm John, because he believes his industry employs some of the brightest minds in business. After much thought, he has concluded that this reputation results from an outdated business model, and he now wants to transform his own company’s approach. John aims to make hourly and project billing a thing of the past, but isn’t quite sure how to do so.

Help John by providing him with some fresh perspectives on innovative consulting business models.

1 OUTLINE BIG ISSUES

• Think of a typical strategy- consulting client.

• Pick the Customer Segment and industry of your choice.

• Describe five of the biggest issues related to strategy consulting. Refer to the Empathy Map (see The Empathy Map).

2 GENERATE POSSIBILITIES

• Take another close look at the five customer issues you selected.

• Generate as many consulting business model ideas as you can.

• Pick the five ideas you think are best (not necessarily the most realistic). Refer to the Ideation Process (see Ideation).

3 PROTOTYPE THE BUSINESS MODEL

• Choose the three most diverse ideas of the five generated.

• Develop three conceptual business model prototypes by sketching the elements of each idea on different Business Model Canvases.

• Annotate the pros and cons of each prototype.