MANAGING MULTIPLE BUSINESS MODELS

Visionaries, game changers, and challengers are generating innovative business models around the world—as entrepreneurs and as workers within established organizations. An entrepreneur’s challenge is to design and successfully implement a new business model. Established organizations, though, face an equally daunting task: how to implement and manage new models while maintaining existing ones.

Business thinkers such as Constantinos Markides, Charles O’Reilly III, and Michael Tushman have a word for groups that successfully meet this challenge: ambidextrous organizations. Implementing a new business model in a longstanding enterprise can be extraordinarily difficult because the new model may challenge or even compete with established models. The new model might require a different organizational culture, or it might target prospective customers formerly ignored by the enterprise. This begs a question: How do we implement innovative business models within long-established organizations?

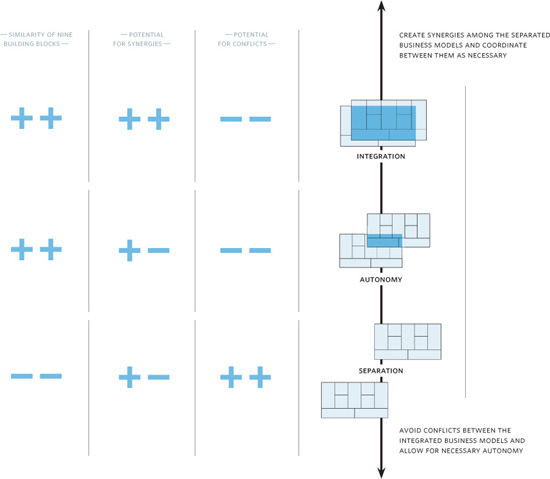

Scholars are divided on the issue. Many suggest spinning off new business model initiatives into separate entities. Others propose a less drastic approach and argue that innovative new business models can thrive within established organizations, either as-is or in separate business units. Constantinos Markides, for example, proposes a two-variable framework for deciding on how to manage new and traditional business models simultaneously. The first variable expresses the severity of conflict between the models, while the second expresses strategic similarity. Yet, he also shows that success depends not only on the correct choice—integrated versus standalone implementation—but also on how the choice is implemented. Synergies, Markides claims, should be carefully exploited even when the new model is implemented in a standalone unit.

Risk is a third variable to consider when deciding whether to integrate or separate an emerging model. How big is the risk that the new model will negatively affect the established one in terms of brand image, earnings, legal liability, and so forth?

During the financial crisis of 2008, ING, the Dutch financial group, was nearly toppled by its ING Direct unit, which provides online and telephone retail banking services in overseas markets. In effect, ING treated ING Direct more as a marketing initiative than as a new, separate business model that would have been better housed in a separate entity.

Finally, choices evolve over time. Markides emphasizes that companies may want to consider a phased integration or a phased separation of business models. e.Schwab, the Internet arm of Charles Schwab, the U.S. retail securities broker, was initially set up as a separate unit, but later was integrated back into the main business with great success. Tesco.com, the Internet branch of Tesco, the giant U.K. retailer, made a successful transition from integrated business line into standalone unit.

In the following pages we examine the issue of integration versus separation with three examples described using the Business Model Canvas. The first, Swiss watch manufacturer SMH, chose the integration route for its new Swatch business model in the 1980s. The second, Swiss foodmaker Nestlé, chose the separation route for bringing Nespresso to the marketplace. As of this writing, the third, German vehicle manufacturer Daimler, has yet to choose an approach for its car2go vehicle rental concept.

SMH’S AUTONOMOUS MODEL FOR SWATCH

In the mid-seventies the Swiss watch industry, which had historically dominated the timepiece sector, found itself in deep crisis. Japanese and Hong Kong watch manufacturers had dislodged the Swiss from their leadership position with cheap quartz watches designed for the low-end market. The Swiss continued to focus on traditional mechanical watches for the mid- and high-end markets, but all the while Asian competitors threatened to intrude on these segments as well.

In the early 1980s competitive pressure intensified to the point that most Swiss manufacturers, with the exception of a handful of luxury brands, were teetering on collapse. Then Nicolas G. Hayek took over the reigns of SMH (later renamed Swatch Group). He completely restructured a newly formed group cobbled together from companies with roots in the two biggest ailing Swiss watchmakers.

Hayek envisioned a strategy whereby SMH would offer healthy, growing brands in all three market segments: low, mid, and luxury. At the time, Swiss firms dominated the luxury watch market with a 97 percent share. But the Swiss owned only 3 percent of the middle market and were non-players in the low end, leaving the entire segment of inexpensive timepieces to Asian rivals.

Launching a new brand at the bottom end was provocative and risky, and triggered fears among investors that the move would cannibalize Tissot, SMH’s middle-market brand. From a strategic point of view, Hayek’s vision meant nothing less than combining a high-end luxury business model with a low-cost business model under the same roof, with all the attending conflicts and trade-offs. Nevertheless, Hayek insisted on this three-tiered strategy, which triggered development of the Swatch, a new type of affordable Swiss watch priced starting at around U.S. $40.

The specifications for the new watch were demanding: inexpensive enough to compete with Japanese offers yet providing Swiss quality, plus sufficient margins and the potential to anchor a larger product line. This forced engineers to entirely rethink the very idea of a timepiece and its manufacture; they were essentially deprived of the ability to apply their traditional watchmaking knowledge.

The result was a watch made with far fewer components. Manufacturing was highly automated: molding replaced screws, direct labor costs were driven down to less than 10 percent, and the watches were produced in large quantities. Innovative guerrilla marketing concepts were used to bring the watch to market under several different designs. Hayek saw the new product communicating a lifestyle message, rather than just telling time on the cheap.

Thus the Swatch was born: high quality at a low price, for a functional, fashionable product. The rest is history. Fifty-five million Swatches were sold in five years, and in 2006 the company celebrated aggregate sales of over 333 million Swatches.

SMH’s choice to implement the low end Swatch business model is particularly interesting in light of its potential impact on SMH’s higher end brands. Despite a completely different organizational and brand culture, Swatch was launched under SMH and not as a standalone entity.

SMH, though, was careful to give Swatch and all its other brands near-complete autonomy regarding product and marketing decisions, while centralizing everything else. Manufacturing, purchasing, and R&D were each regrouped under a single entity serving all of SMH’s brands. Today, SMH maintains a strong vertical integration policy in order to achieve scale and defend itself against Asian competitors.

SMH is vertically integrated and centralized with respect to production,

R&D, sourcing and HR.

Each SMH brand enjoys autonomy regarding product, design, and marketing communication decisions.

THE NESPRESSO SUCCESS MODEL

Another ambidextrous organization is Nespresso, part of Nestlé, the world’s largest food company with 2008 sales of approximately U.S. $101 billion.

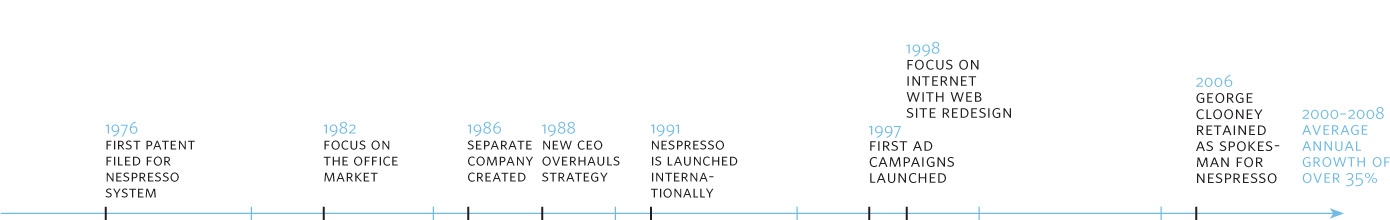

Nespresso, which each year sells over U.S.$1.9 billion worth of single-serve premium coffee for home consumption, offers a potent example of an ambidextrous business model. In 1976, Eric Favre, a young researcher at a Nestlé research lab, filed his first patent for the Nespresso system. At the time Nestlé dominated the huge instant coffee market with its Nescafé brand, but was weak in the roast and ground coffee segments. The Nespresso system was designed to bridge that gap with a dedicated espresso machine and pod system that could conveniently produce restaurant-quality espresso.

An internal unit headed by Favre was set up to eliminate technical problems and bring the system to market. After a short, unsuccessful attempt to enter the restaurant market, in 1986 Nestlé created Nespresso SA, a wholly-owned subsidiary that would start marketing the system to offices in support of another Nestlé joint venture with a coffee machine manufacturer already active in the office segment. Nespresso SA was completely independent of Nescafé, Nestlé’s established coffee business. But by 1987 Nespresso’s sales had sagged far below expectations and it was kept alive only because of its large remaining inventory of high-value coffee machines.

In 1988 Nestlé installed Jean-Paul Gaillard as the new CEO of Nespresso. Gaillard completely overhauled the company’s business model with two drastic changes. First, Nespresso shifted its focus from offices to high-income households and started selling coffee capsules directly by mail. Such a strategy was unheard of at Nestlé, which traditionally focused on targeting mass markets through retail Channels (later on Nespresso would start selling online and build high-end retail stores at premium locations such as the Champs-Élysées, as well as launch its own in-store boutiques in high-end department stores). The model proved successful, and over the past decade Nespresso has posted average annual growth rates exceeding of 35 percent.

Of particular interest is how Nespresso compares to Nescafé, Nestlé’s traditional coffee business. Nescafé focuses on instant coffee sold to consumers indirectly through mass-market retailers, while Nespresso concentrates on direct sales to affluent consumers. Each approach requires completely different logistics, resources, and activities. Thanks to the different focus there was no risk of direct cannibalization. Yet, this also meant little potential for synergy between the two businesses. The main conflict between Nescafé and Nespresso arose from the considerable time and resource drain imposed on Nestlé’s coffee business until Nespresso finally became successful. The organizational separation likely kept the Nespresso project from being cancelled during hard times.

The story does not end there. In 2004 Nestlé aimed to introduce a new system, complementary to the espresso-only Nespresso devices, that could also serve cappuccino and lattes. The question, of course, was with which business model and under which brand should the system be launched? Or should a new company be created, as with Nespresso? The technology was originally developed at Nespresso, but cappuccinos and lattes seemed more appropriate for the mid-tier mass market. Nestlé finally decided to launch under a new brand, Nescafé Dolce Gusto, but with the product completely integrated into Nescafé’s mass-market business model and organizational structure. Dolce Gusto pods sell on retail shelves alongside Nescafé’s soluble coffee, but also via the Internet—a tribute to Nespresso’s online success.