Seven

ON THE ROAD

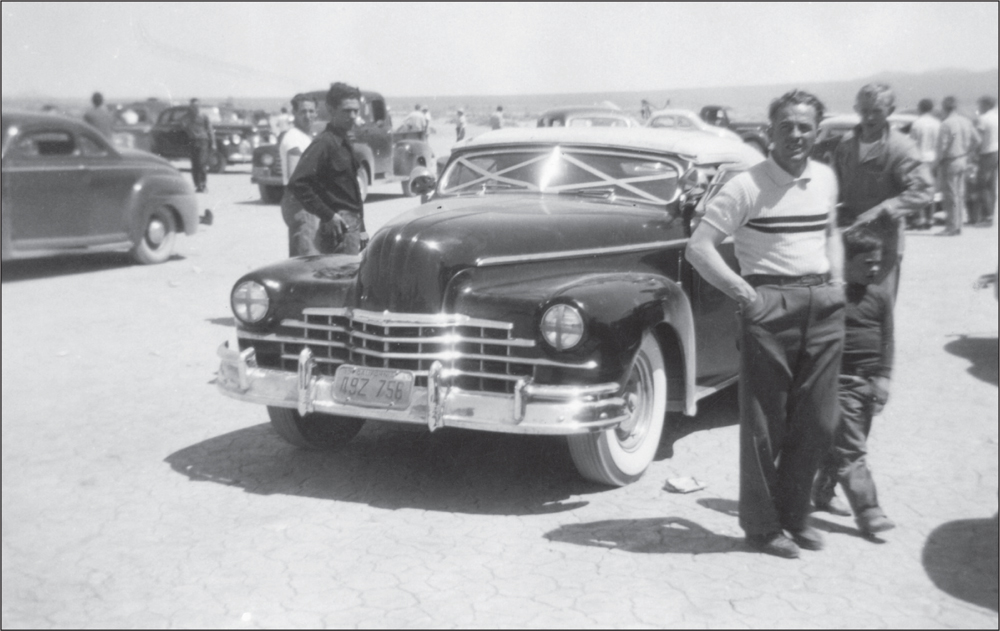

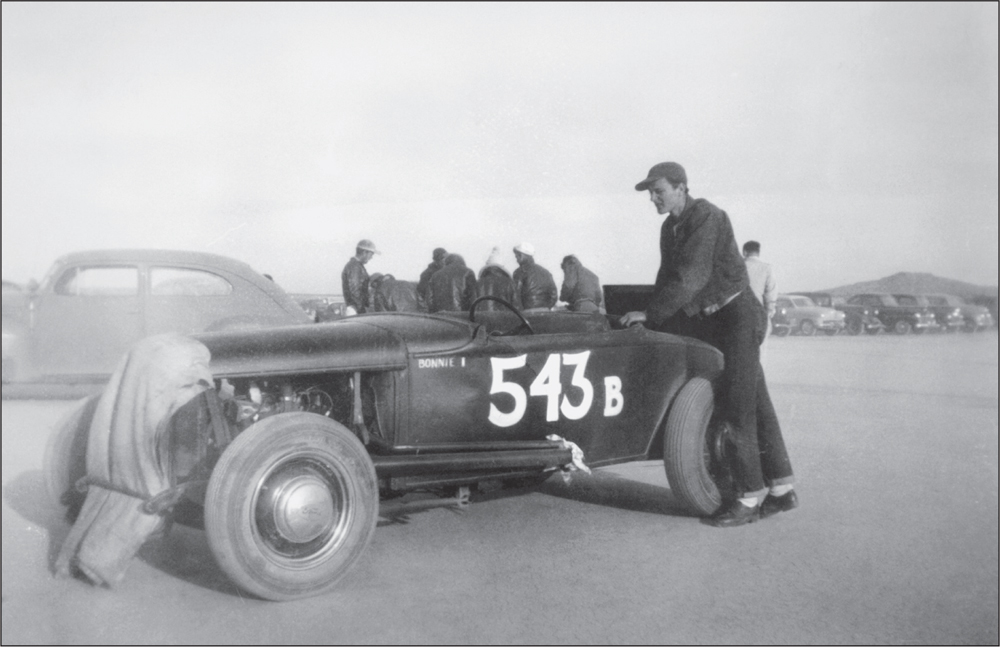

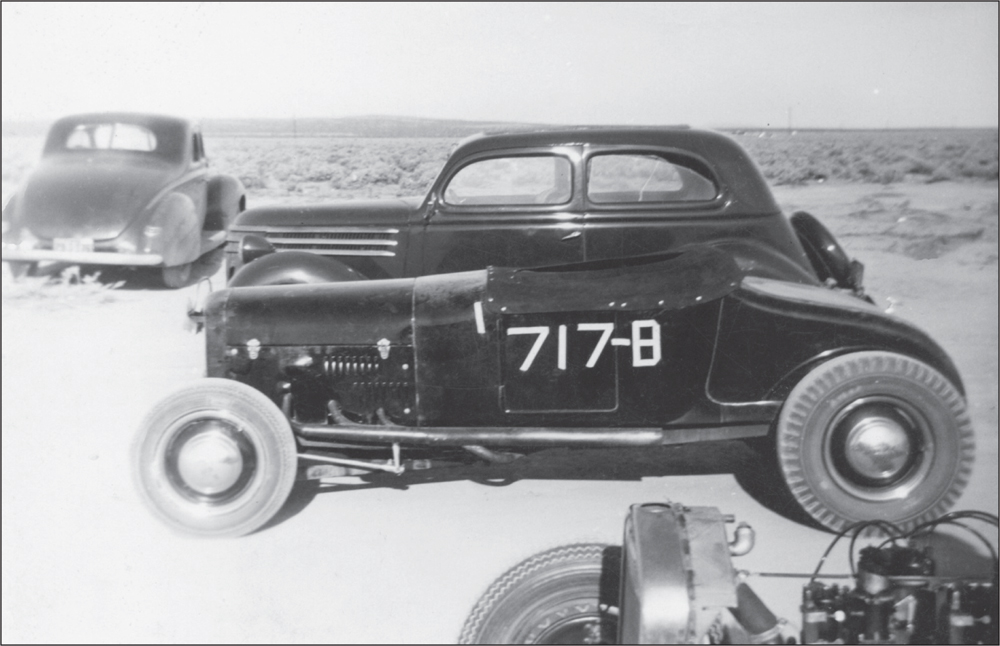

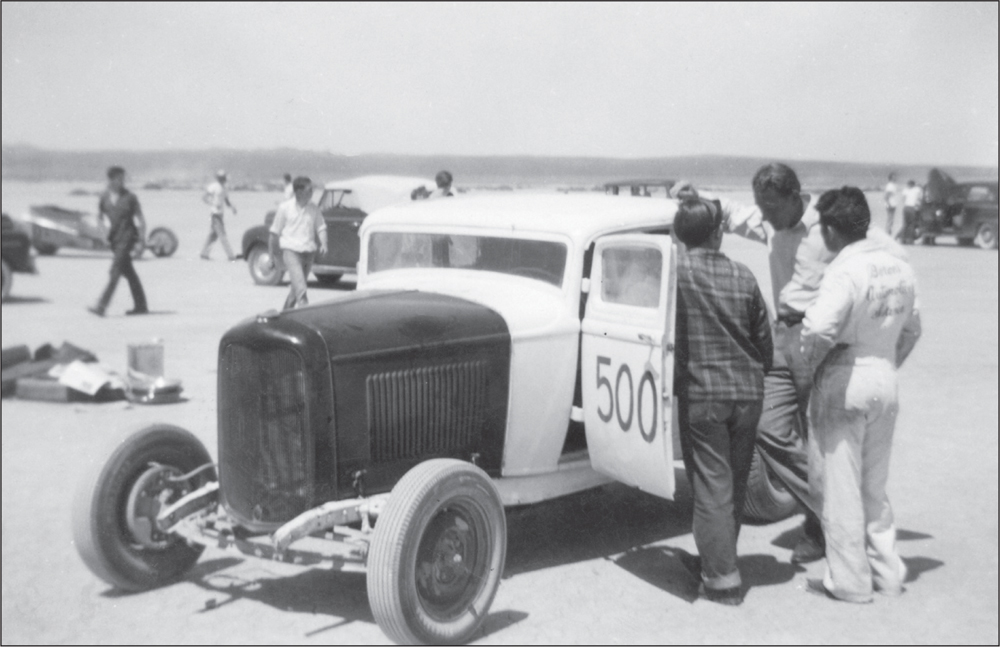

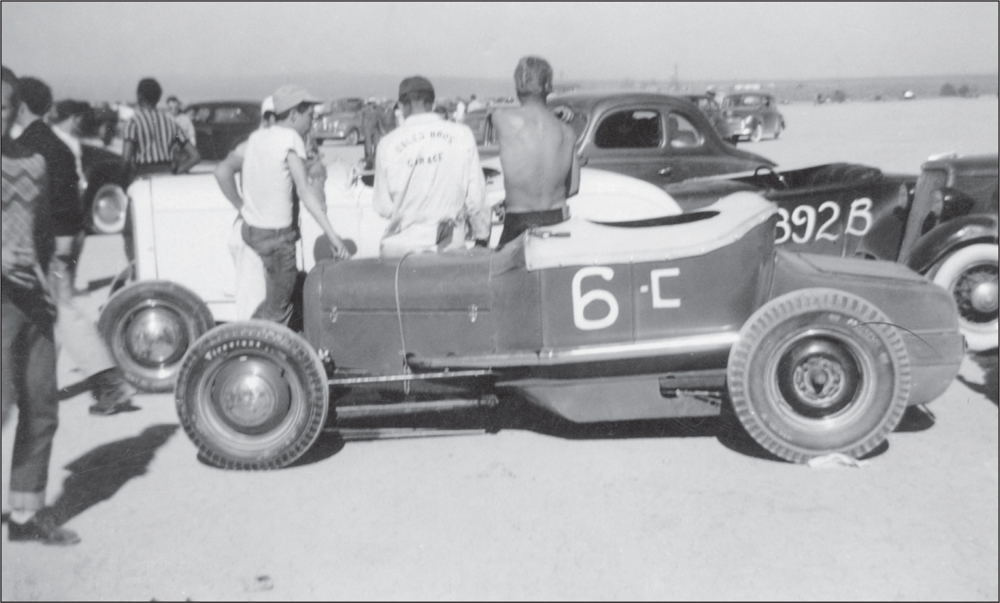

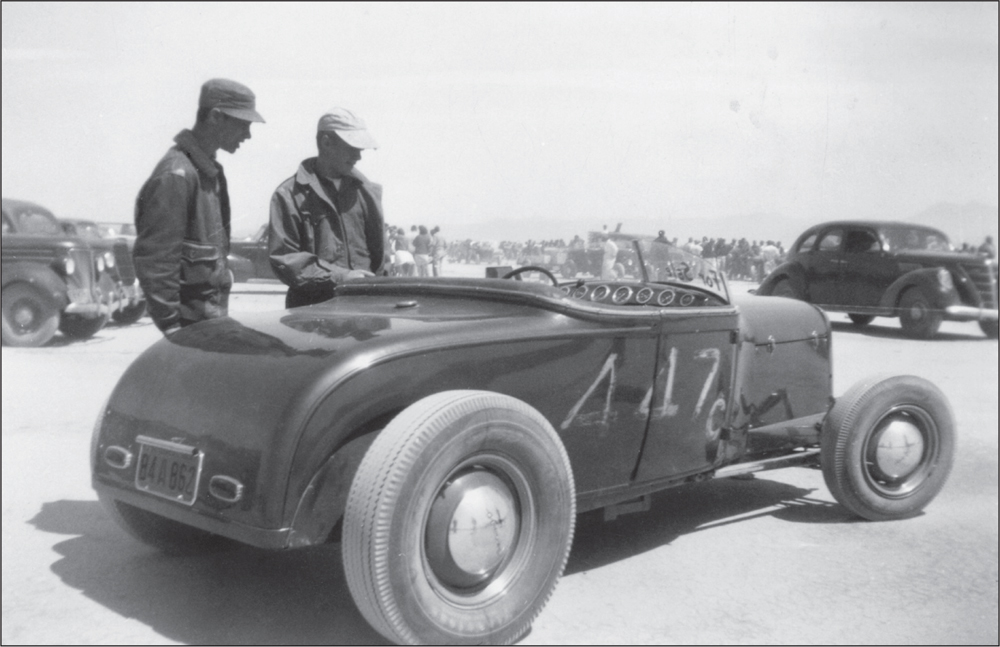

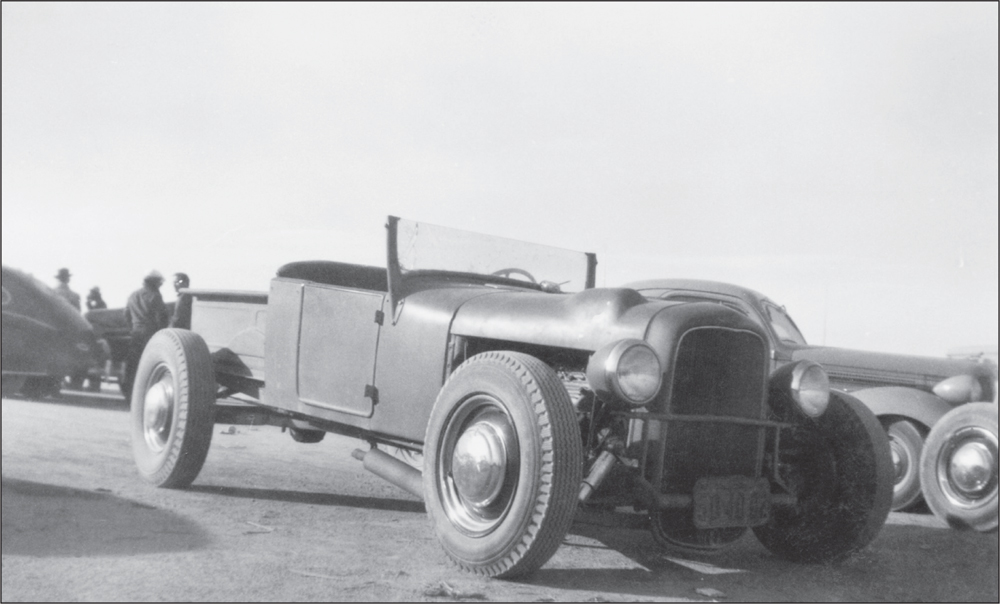

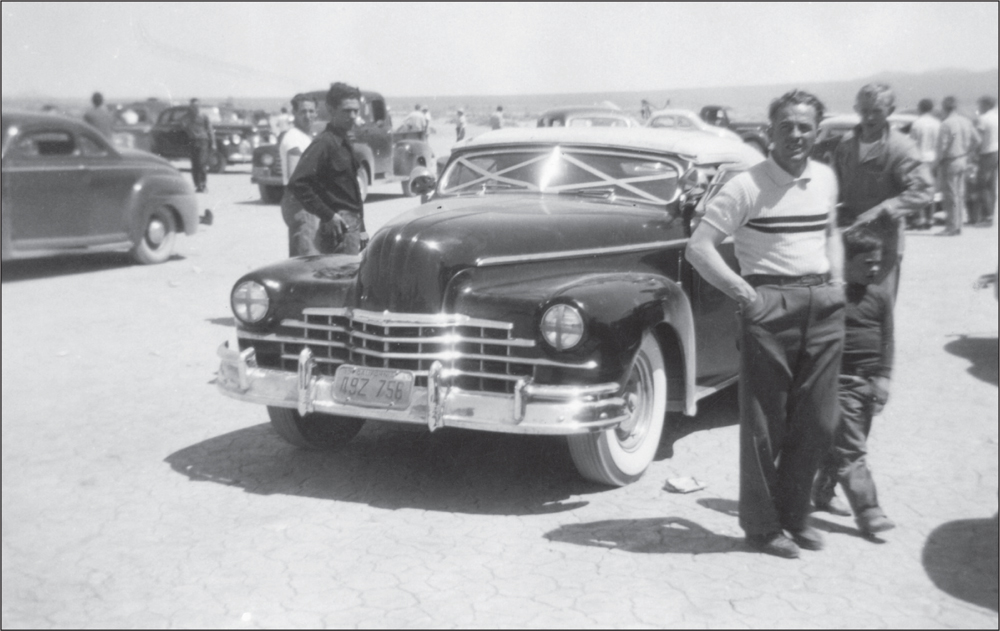

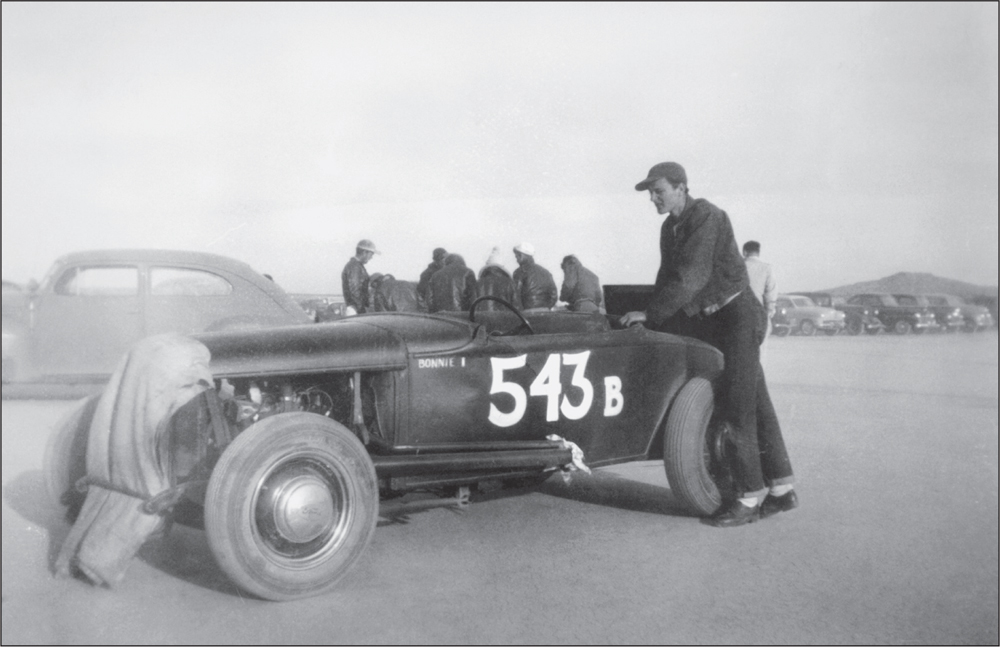

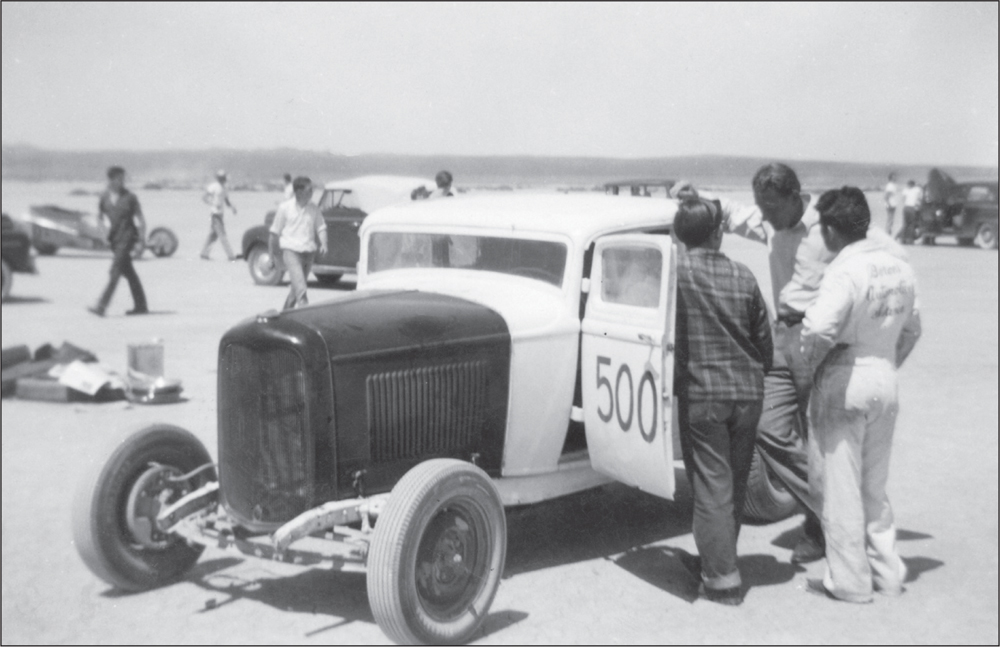

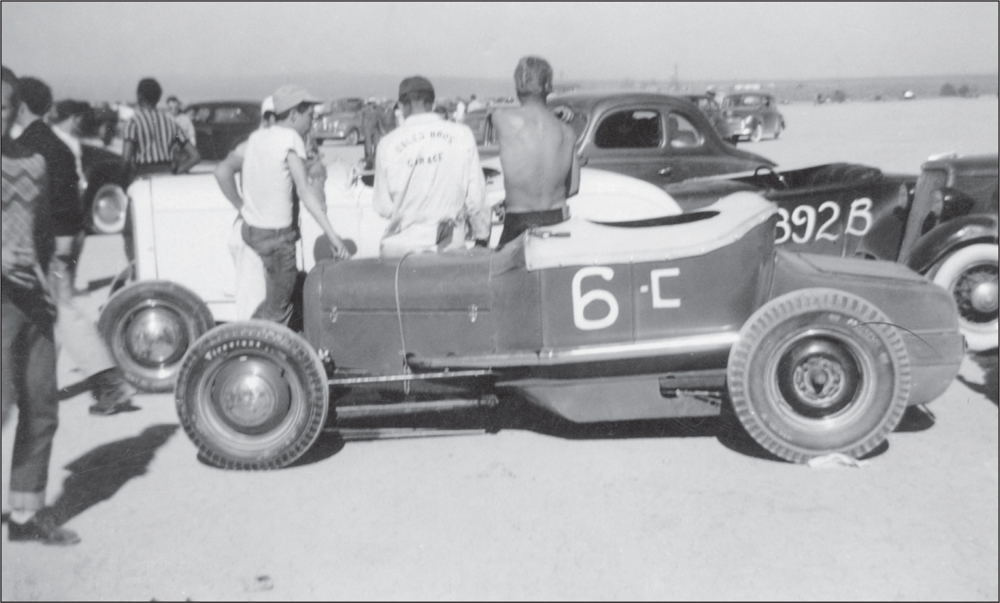

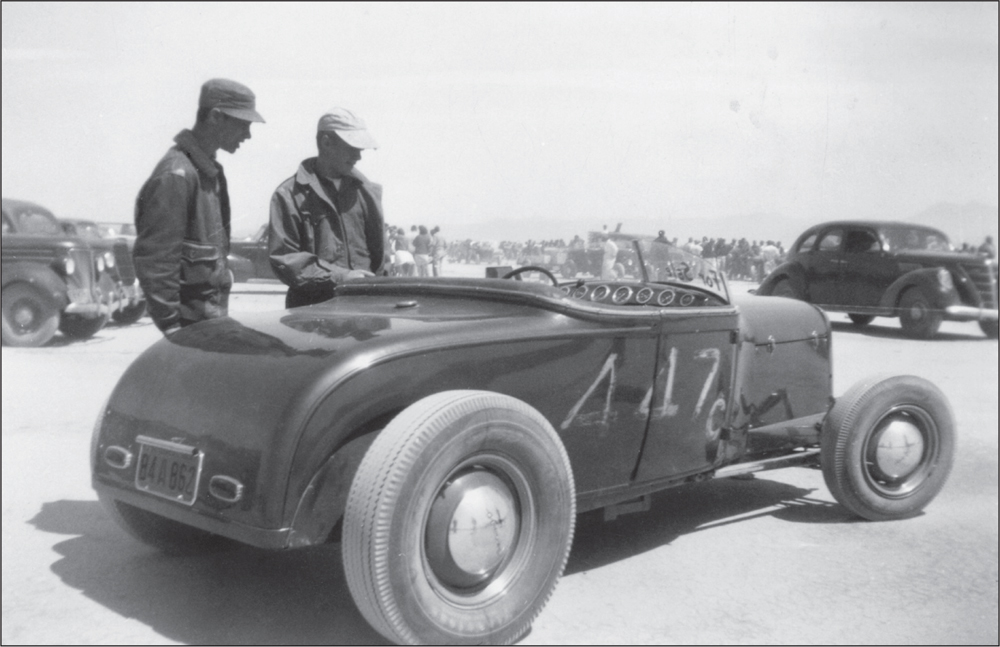

In the days before drag strips were established, “acceleration meets” were held in the desert east of the coast at El Mirage Dry Lake, attracting hot-rodders from all over California, including Santa Barbara County. Here are some images from the albums of Lee Hammock and Jack Chard showing some of the early postwar activities at El Mirage, as well as some from later on, when the action moved to the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah. (Courtesy of Jack Chard.)

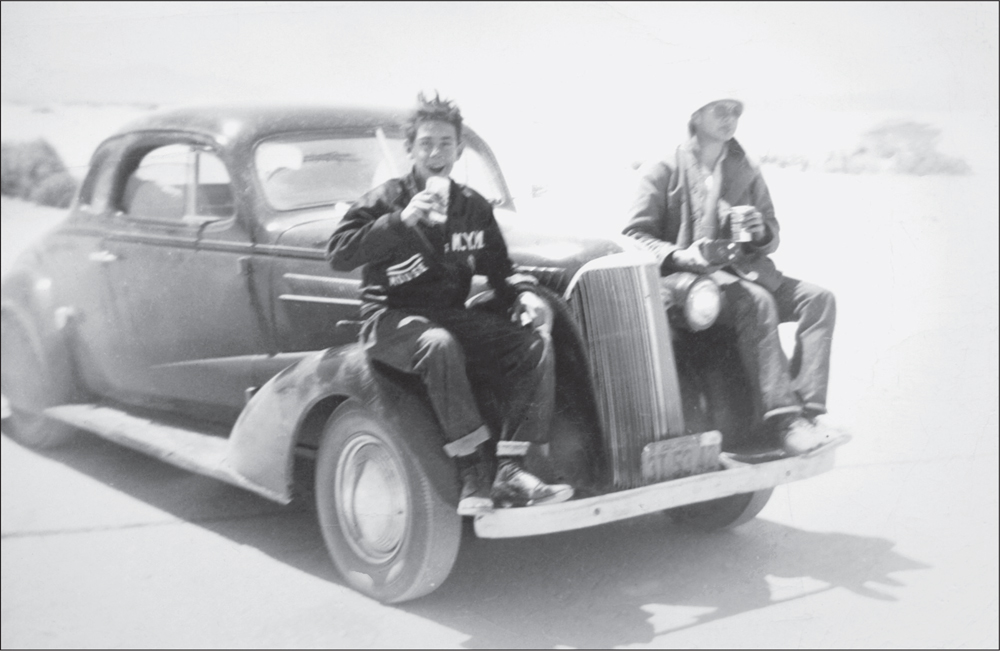

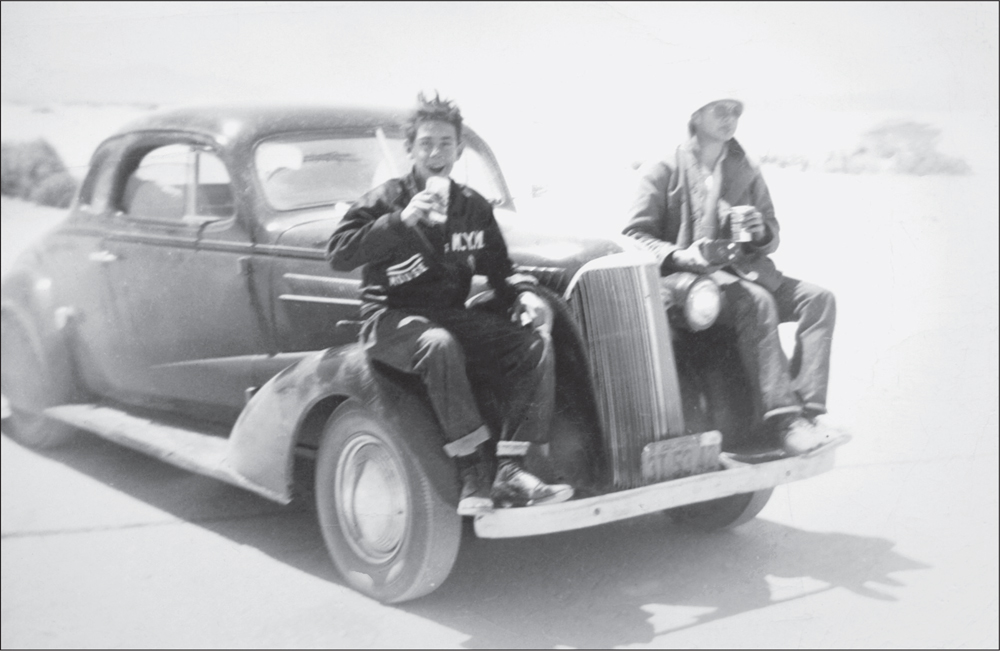

Santa Barbara residents Fielding Lewis (left) and Steve Tilford are seen enjoying a cooling beverage under the late-morning sun at El Mirage. They are seated on the fenders of Lee Hammock’s 1937 Chevrolet while observing the timing trials. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

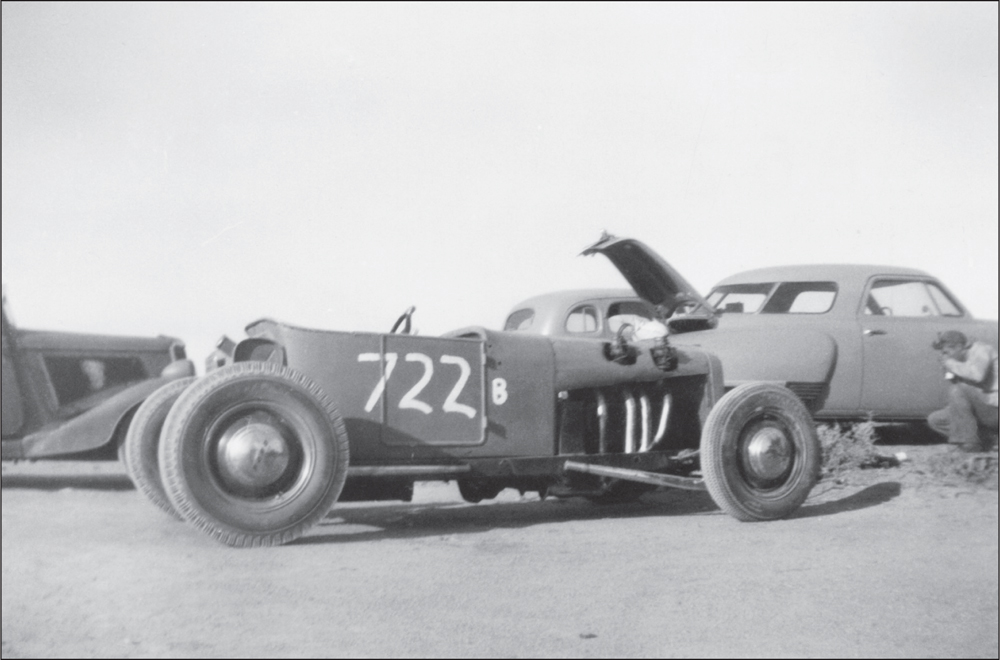

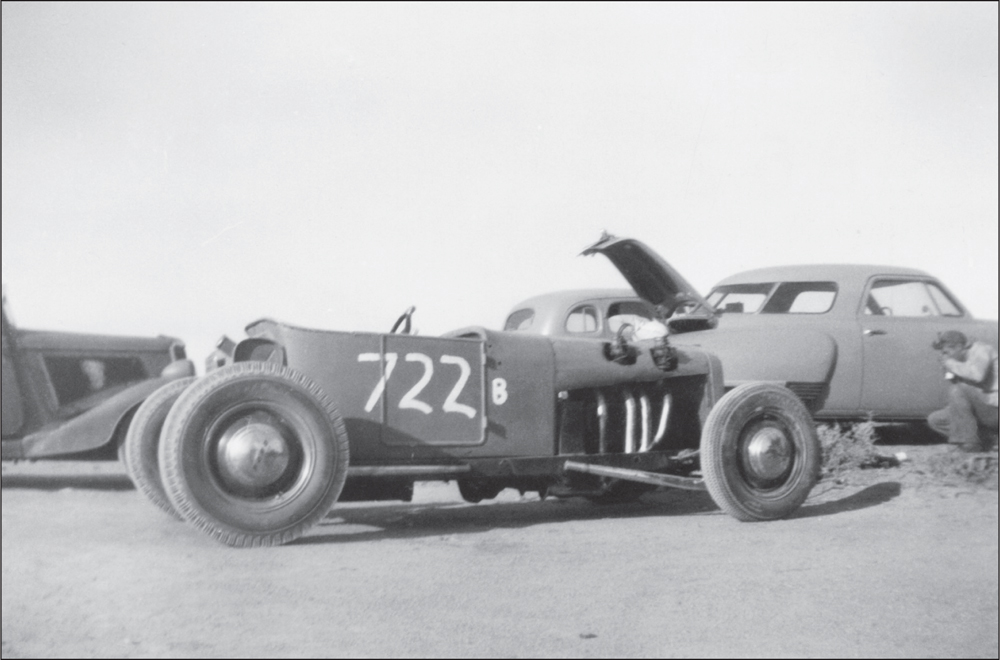

Here is an interesting 1927 Model T bucket roadster Lee Hammock snapped at El Mirage Dry Lake in 1950. Powered by a four-cylinder Model A engine equipped with two carburetors, this roadster was a typical lake racer. Note the 1934 Ford Coupe and new 1950 Studebaker Commander in the background. (Both, courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

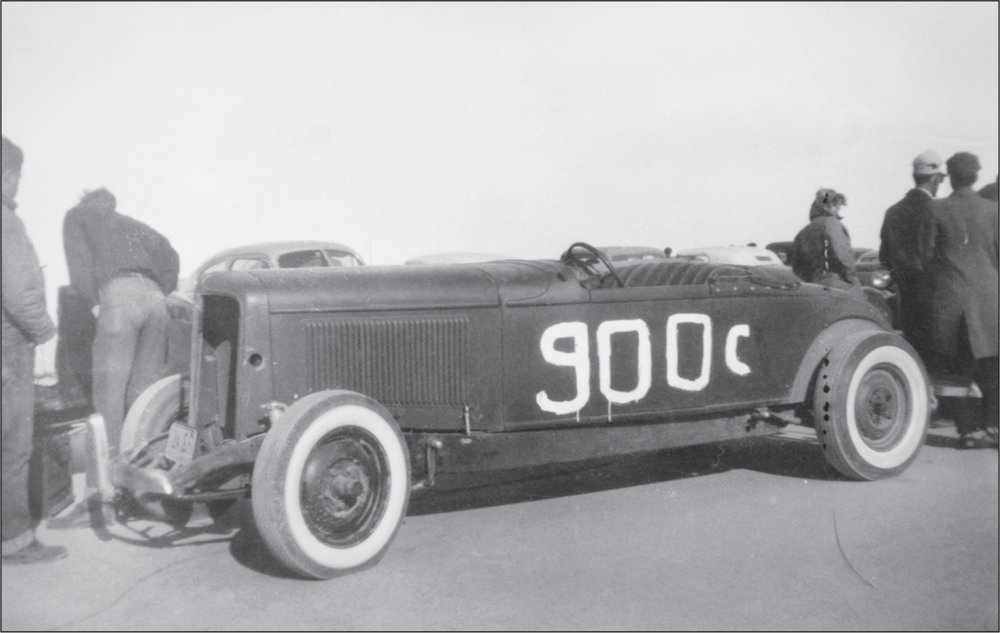

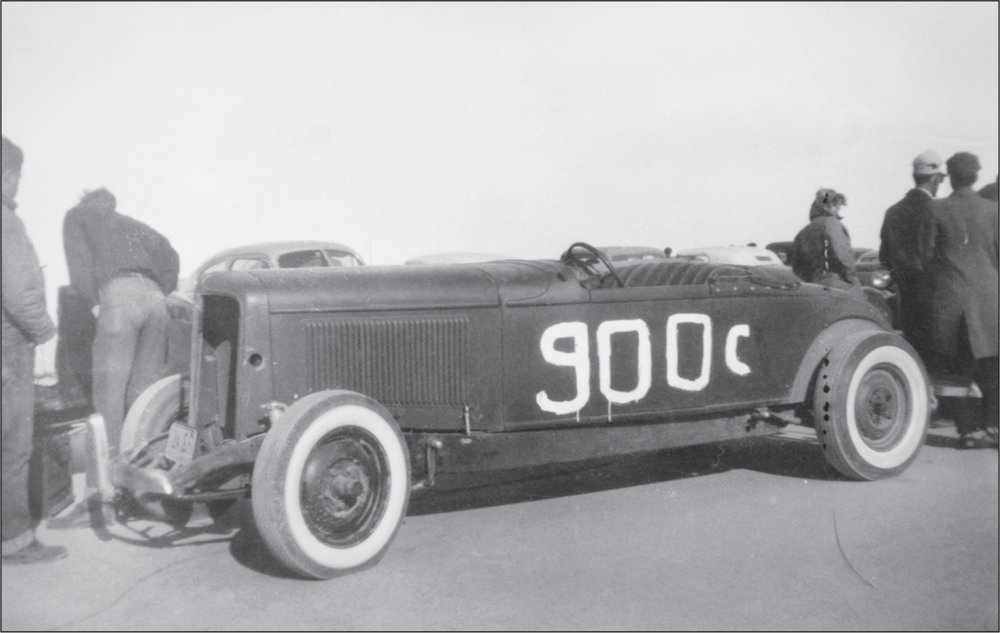

A hot rod seen regularly at El Mirage was this 1927 T roadster belonging to Bill Lyons. Famous in its day for having appeared in Hot Rod Magazine, this well-finished gold beauty has lots of chrome and sported a 1932 grill shell. Also visible is a set of Kenmont brakes, an early disc-brake system designed in the late 1930s. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

This group, clad in war-surplus clothing, is checking out a highly modified Model T roadster on a cold, clear morning at El Mirage in 1947. That is an Essex radiator shell up front on this lake racer car; note the homemade cross-tread lake tires on the rear. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

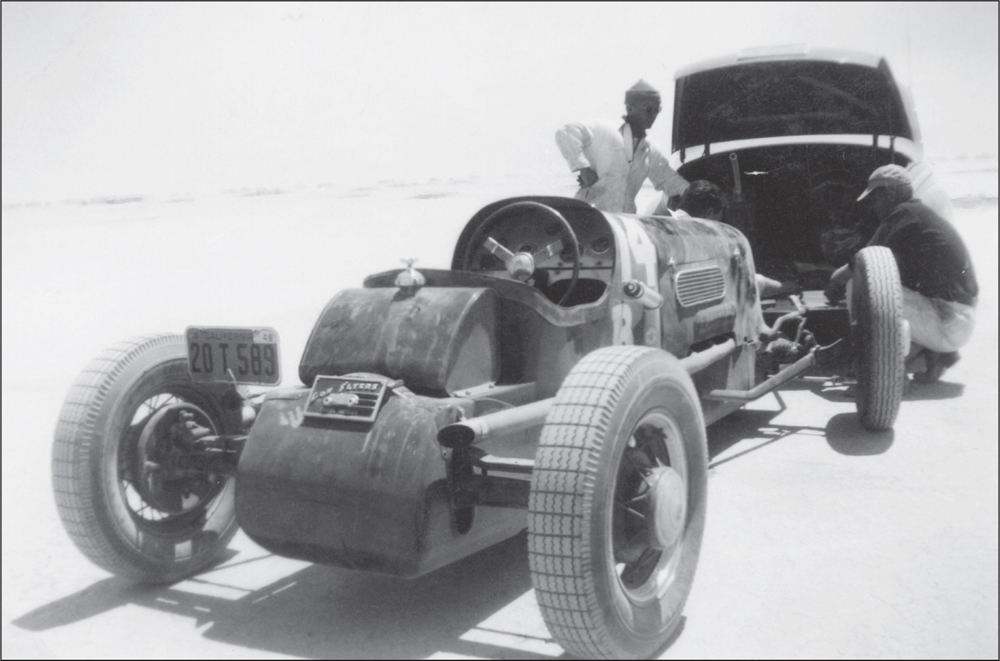

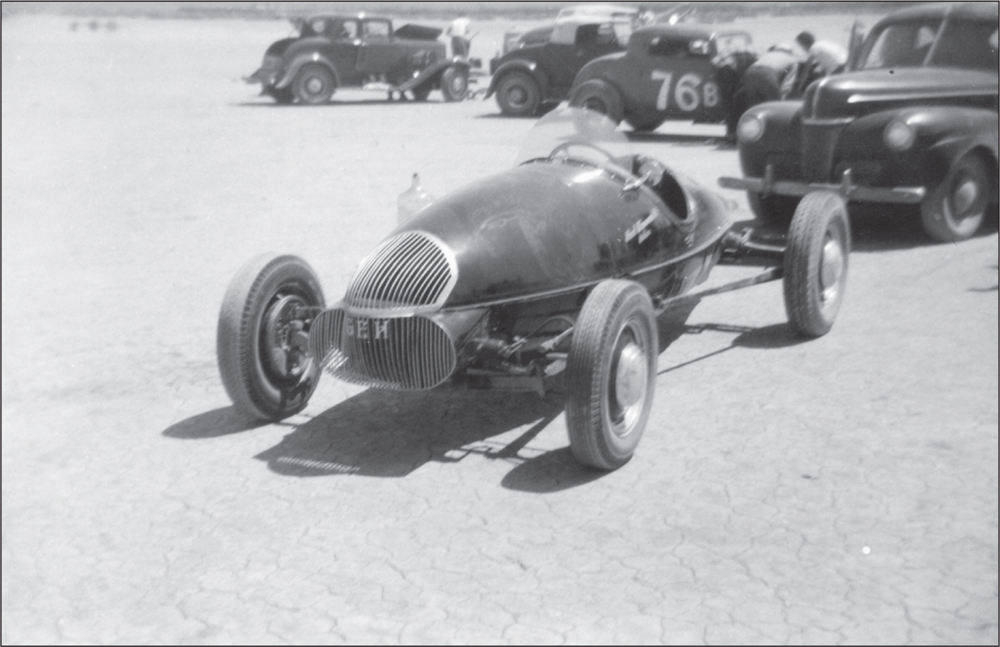

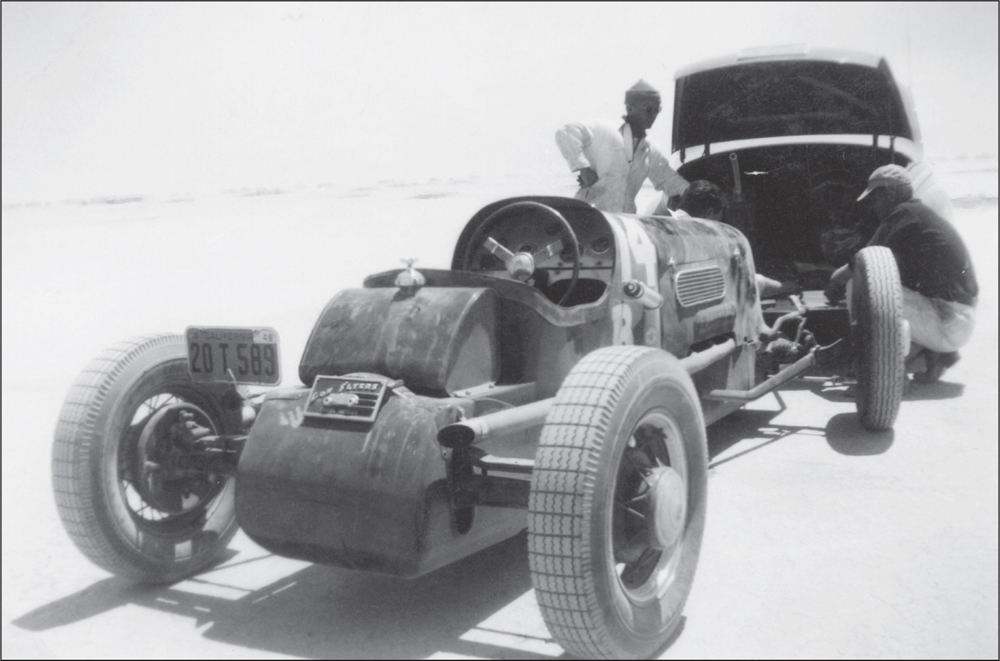

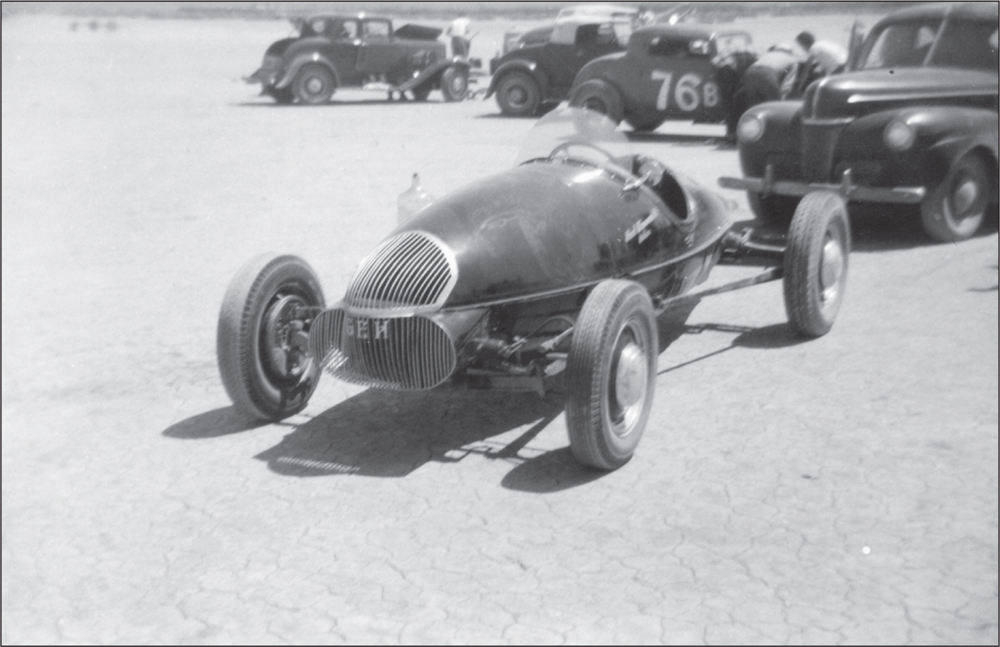

Here is a neat little sprint car that saw double duty as a lake racer at El Mirage sometime in the late 1940s. Probably built in the late 1930s, this solid-looking racer appears especially well constructed. The club plaque on the back reads, “Con Flyers, Santa Monica.” (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

One could see almost anything competing in timing runs at El Mirage, including customs. This black-and-primer 1947 Mercury has an interesting front grill treatment, and the headlights and part of the windshield are well taped for safety. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

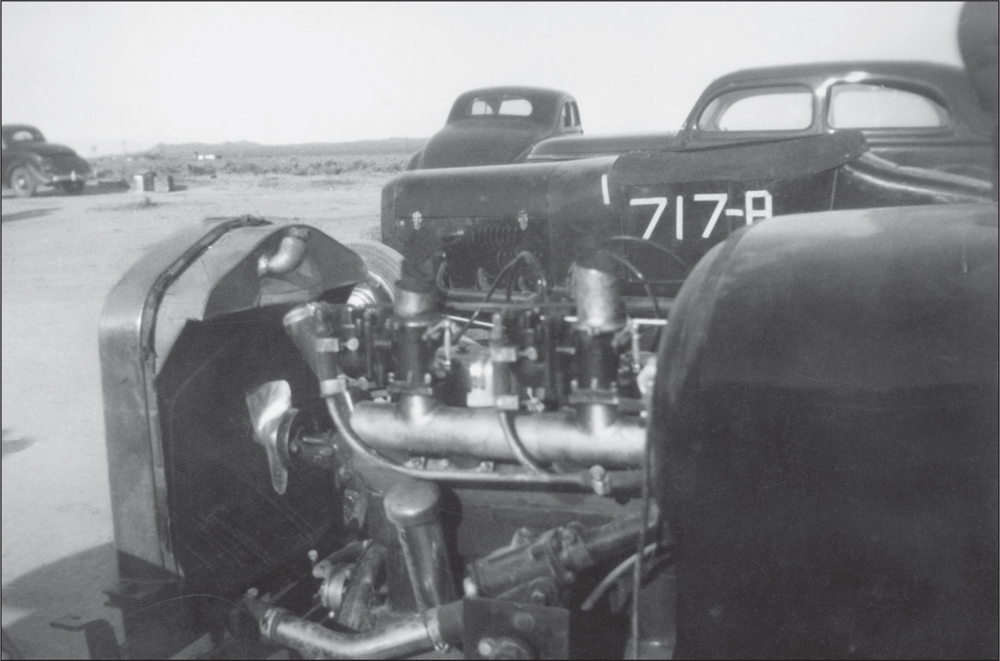

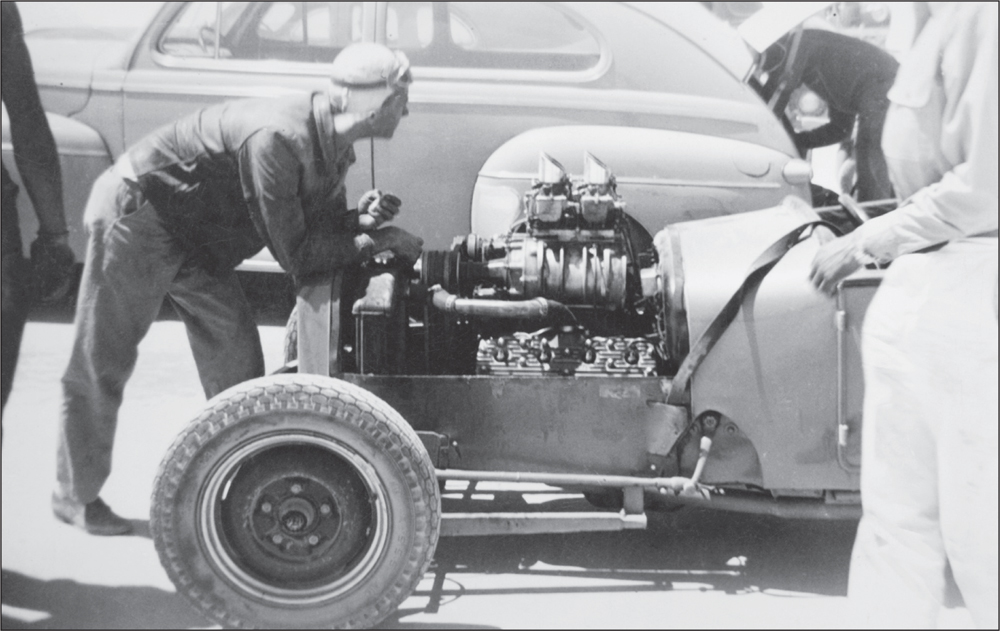

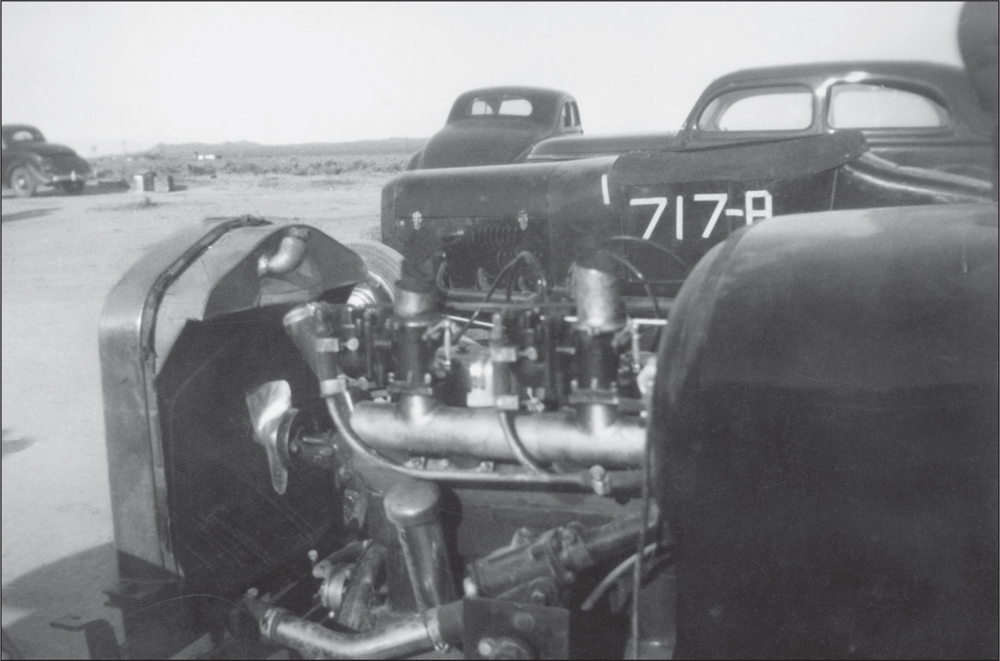

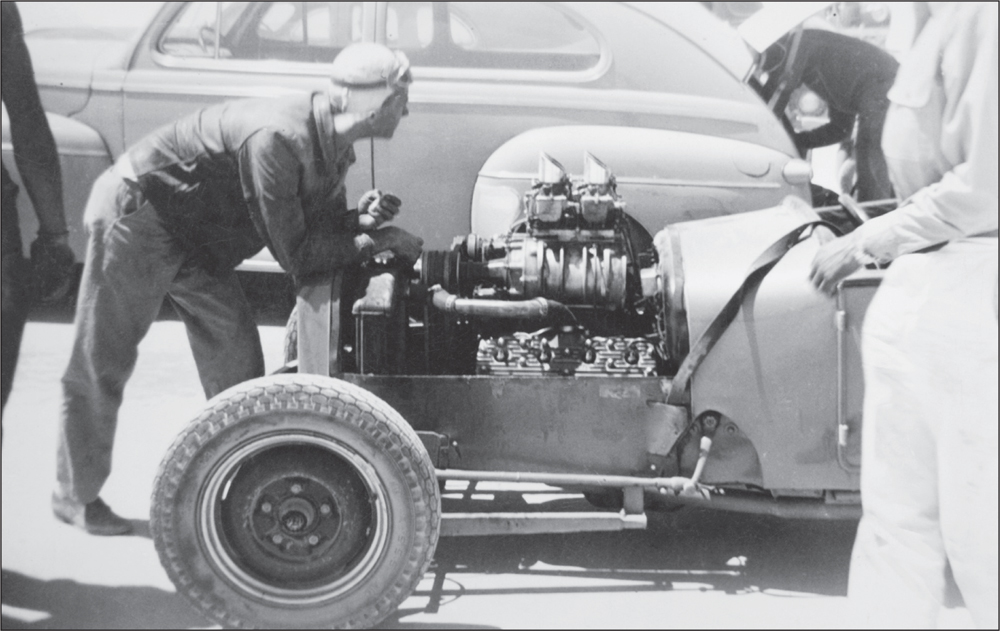

In this view looking out across the lake bed at El Mirage, the engine in the rod visible in the foreground is a Ford four-cylinder with a four-port Riley Head. Behind that is a V-8–powered 1927 Model T roadster with a 1932 grill shell. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

This custom looks like it might have started life as a 1947 Mercury. It has been nosed, and its headlights, frenched, and that is a Cadillac grill up front. A Carson top and a pair of spotlights have also been added. Note how the windshield and headlights have been taped to prevent shattering in the event of a rock strike. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

This shot captures the atmosphere of the early-morning meets at El Mirage well. The owner of this 1931 Ford roadster has wrapped the rod’s radiator with a blanket to help keep it warm in the chilly air. The exhaust pipes coming out of the flathead V-8 have been plugged to keep out the morning dew. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

This 1927 Model T roadster is seen sitting in the staging area at El Mirage around 1947. From the triple-header exhaust coming out of the side panel, it looks like it is powered by a flathead V-8. In the background is a 1935 Ford Tudor sedan. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

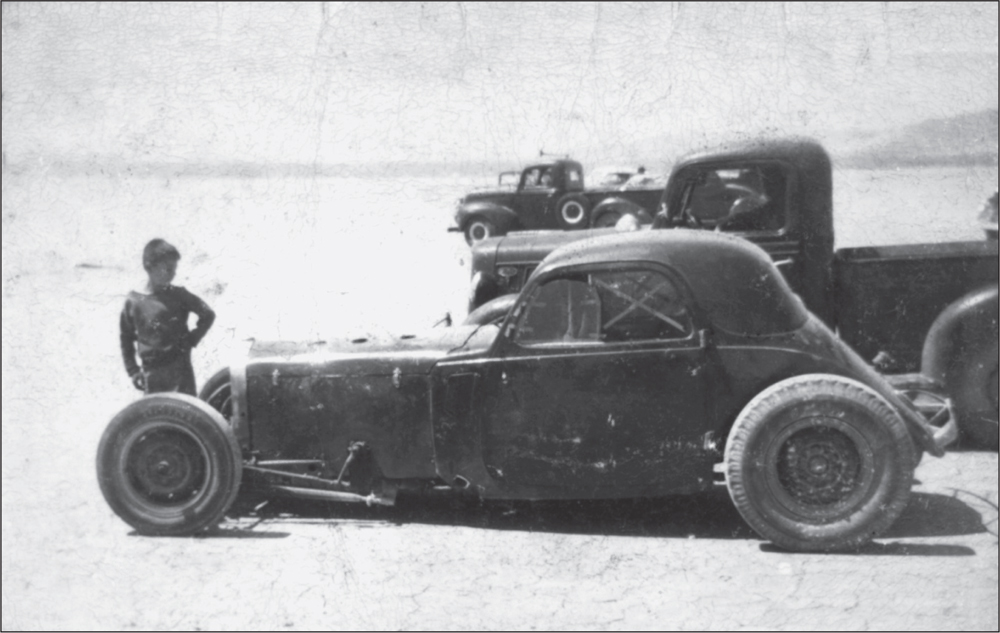

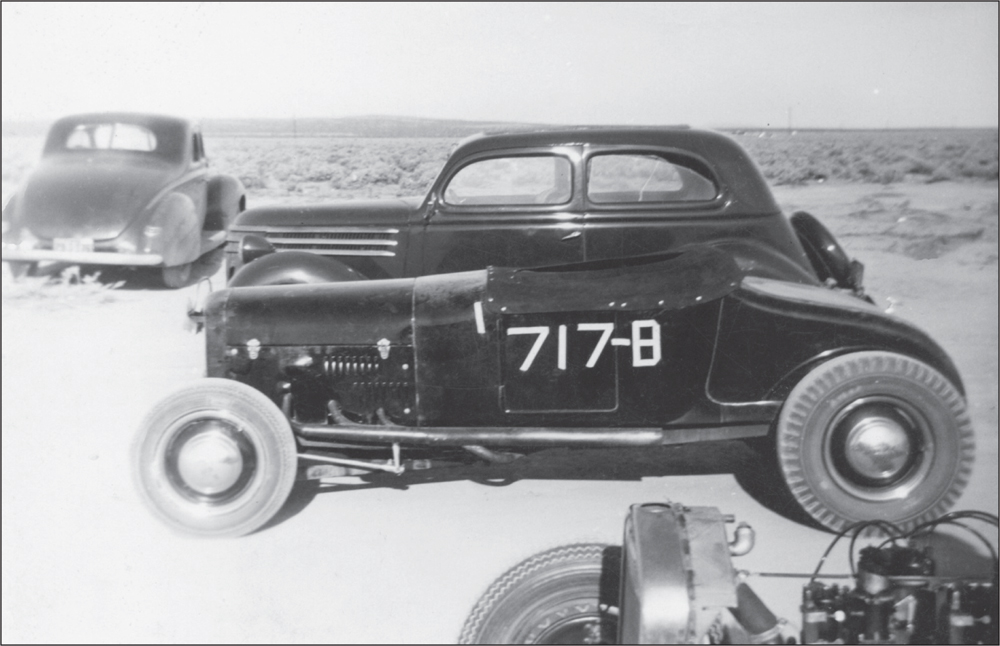

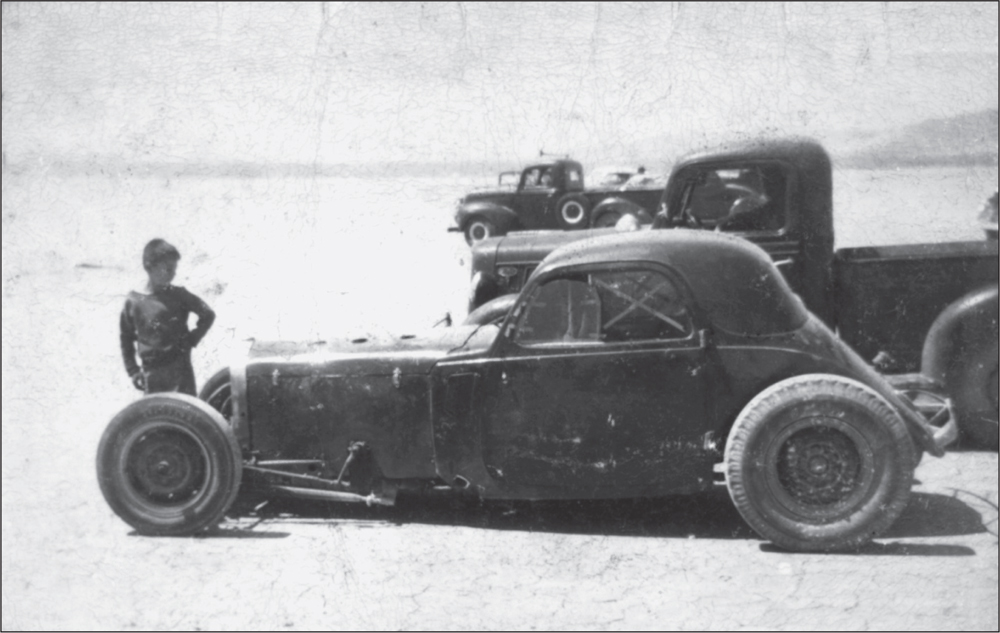

This 1932 Ford coupe was owned and driven by none other than well-known hot-rodder Lou Baney, cofounder of Saugus Drag Strip. The black-and-white Deuce coupe looks like it has been chopped about four inches. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

Tank racers, made from war-surplus aviation fuel tanks, were popular platforms for timing runs at El Mirage. This one is powered by a small, lightweight Crosley four-cylinder APU (auxiliary power unit) engine, another war surplus item. Note the homemade wire grill. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

While the scene at El Mirage was dominated by Ford products, other makes did show up. A particular rarity in 1947 was this big V-16–powered 1932 Marmon roadster. Marmons had the reputation of being fast and powerful cars. A survivor of the wartime scrap-metal drives, this one may have been owned by Howard Johanssen of Howard’s Cams. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

This 1947 image shows a 1927 T-bucket lake racer ready to start a timing run. Note the big lake tires on the rear and the way the radiator shell has been moved behind the front suspension. The sedan visible in the right background is a Southern California Timing Association safety-patrol vehicle. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

This 1947 photograph, which Lee Hammock carried around in his wallet for many years, shows the beginning of what later became a popular trend in drag racing: the use of small European cars—such as English Fords or, in this case, Italian Fiats—as the basis for lake racers or dragsters. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

Some of the first blowers or superchargers were seen on the El Mirage lake bed in the very early days. The one mounted on this roadster’s flathead engine looks like it has four Stromberg 97 carburetors sitting on top. Note the white, cloth, 1930s-style racing helmet on the fellow leaning on the radiator at left. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

Parked between a 1934 coupe and a 1940 deluxe at El Mirage is this unusual Deuce coupe. Behind the nerf bar is a strange-looking dual-radiator grill setup combining a 1932 shell with a forward fairing that looks like it may be made up of Buick grill parts. This was all part of a belly pan that stretched underneath the car to the rear end. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

Phil Schindler’s 1927 T-bucket has gained a new paint job and race number in this shot, which also shows the belly pan to good advantage. Traveling along the rough lake bed at 100 miles per hour, the tires could kick up quite a lot of dust and debris into the cockpit. This plus the fact that these old racers rode rather low made the protection a belly pan offered pretty attractive. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

This sharp, full-fendered Deuce coupe was photographed by Lee Hammock sometime in the late 1940s at El Mirage. The black beauty looks like it has about a four-inch chop, and check out the very cool chrome-plated grill shell and smaller headlamps. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

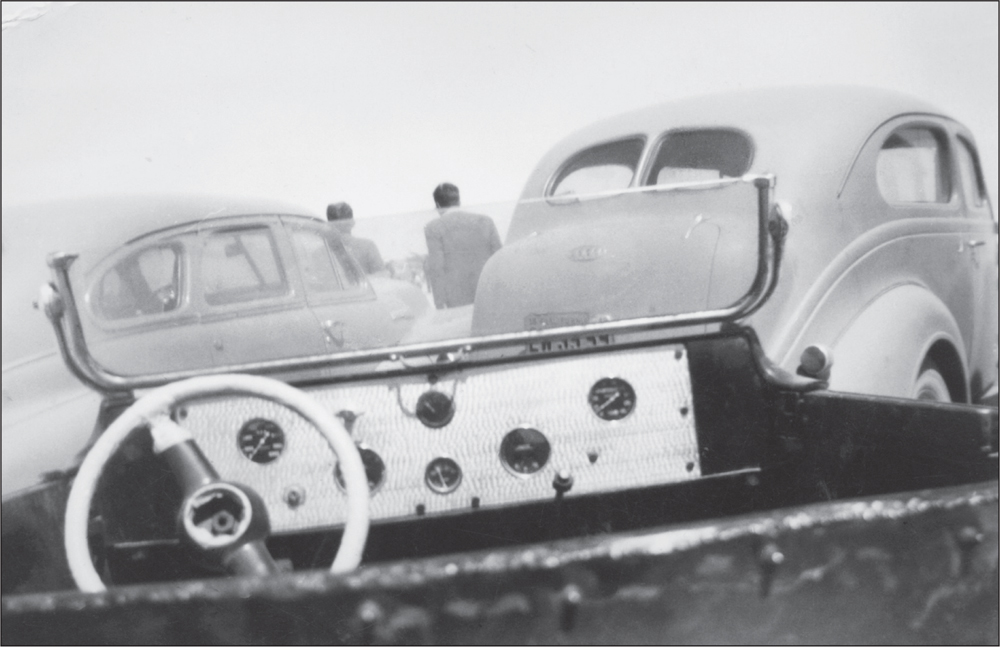

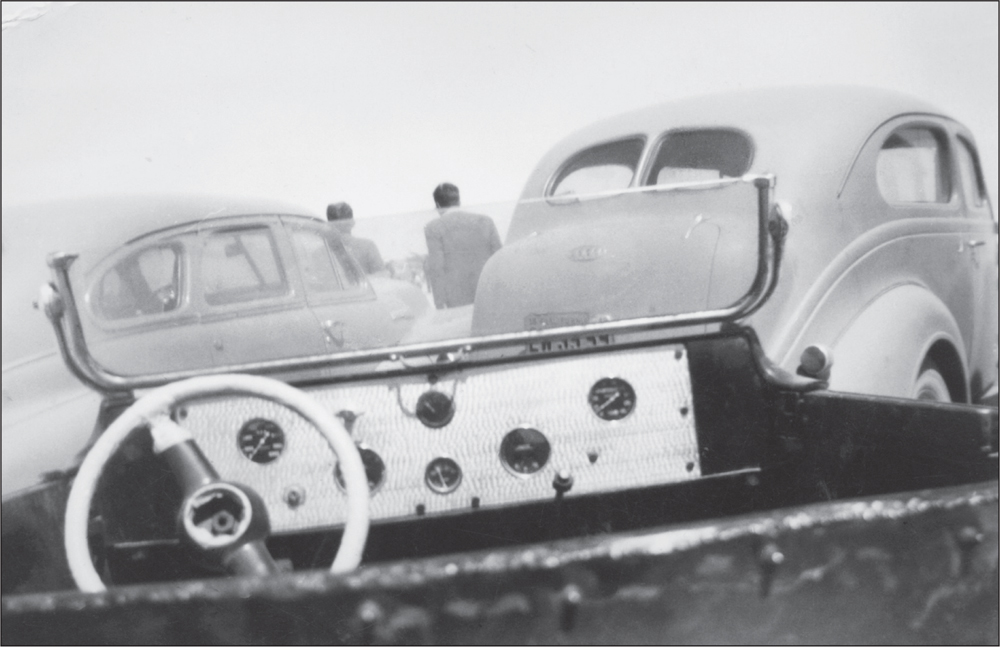

This is a great view of the pit area at El Mirage as seen from atop a 1929 Ford roadster. With all the action going on in the background, it would be easy to ignore this well-appointed hot rod. Beneath the homemade custom windshield, the dashboard displays a full array of Stewart-Warner gauges, very expensive in their day. Also, note the 1940 Ford steering wheel and column shift. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

Here is the same car viewed from another angle. This very well-finished Deuce roadster may have been built by Jack Caloric, a well-known Los Angeles hot rod builder. He has installed Chevrolet taillight lenses on the decked rear end. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

As the hot rod usually reflected the personality and budget of the owner, so did the rod’s interior. This 1932 Ford roadster is equipped with a complete Stewart-Warner gauge set, including a chrome metal dash-panel insert. Other popular alternatives were Auburn dashboards and even speedboat dashes. Note the Mercury steering wheel and column shift. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

Not all hot-rodders drove Fords. This is Lee Hammock’s black 1937 Chevrolet coupe. These cars were popular for their sleek Art Deco styling. And, equipped with a strong, reliable in-line six-cylinder overhead engine, they could move too. Lee tuned his engine with a hot camshaft, ported head, and dual-carburetor intake manifold. Note the fender skirts. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

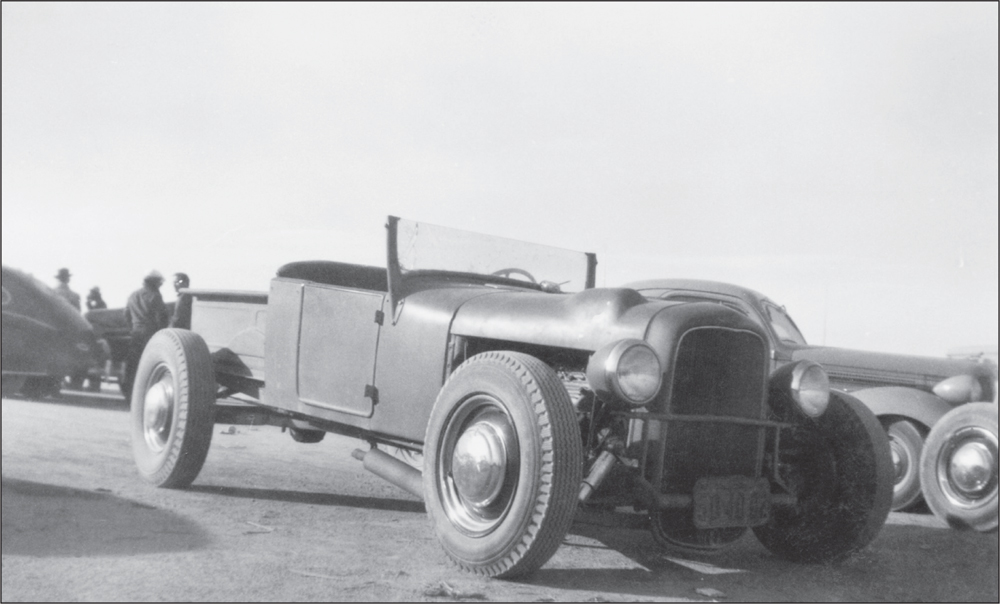

This and the following image from El Mirage in 1947 show a very interesting hot rod made of a conglomeration of different parts. The cockpit came from a 1926 or 1927 Ford Phaeton. Note how the body has been cut in a straight line behind the door. The Model A pickup bed has been moved forward on the frame, as evidenced by the location of the wheel arch. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

At the front, the Deuce radiator shell has had the bottom trimmed to drop down over the 1929 frame for a low, cooler look. The headlights, possibly from a 1936 Ford, rest on a simple bar. That bulge on the hood is most likely covering the generator that is sitting atop an early 21-stud flathead V-8. This is the kind of hot rod that was driven, rather than towed, to the meet. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

Wes Jacobs of Santa Barbara (left) and Bob Burnett of Montecito pose with a nice-looking rearengined lake racer at El Mirage around 1948. This car went through many different modifications throughout its career. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

Here is another interesting dashboard treatment. The owner of this late-1920s Dodge hot rod has taken a rectangular piece of fine veneer and mounted a full set of aftermarket gauges on it. The steering wheel looks like it came from a 1940 Ford Deluxe. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

Stoddard Hensling of Santa Barbara poses at El Mirage Dry Lake with his primer-gray 1932 Ford Deuce roadster. Note the tow bar and the tube shocks on the front end. Tube shocks were beginning to replace the older lever-action or friction shocks by the late 1940s. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

Here is a good example of an early attempt at aerodynamic design, or streamlining, as it was called. This 1927 roadster has had the front axles faired over and a belly pan installed. The color is gold metallic, with some patchwork visible on the extreme nose. The cross-treads on the rear tires were cut by hand with a hot iron for better traction on the lake bed. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

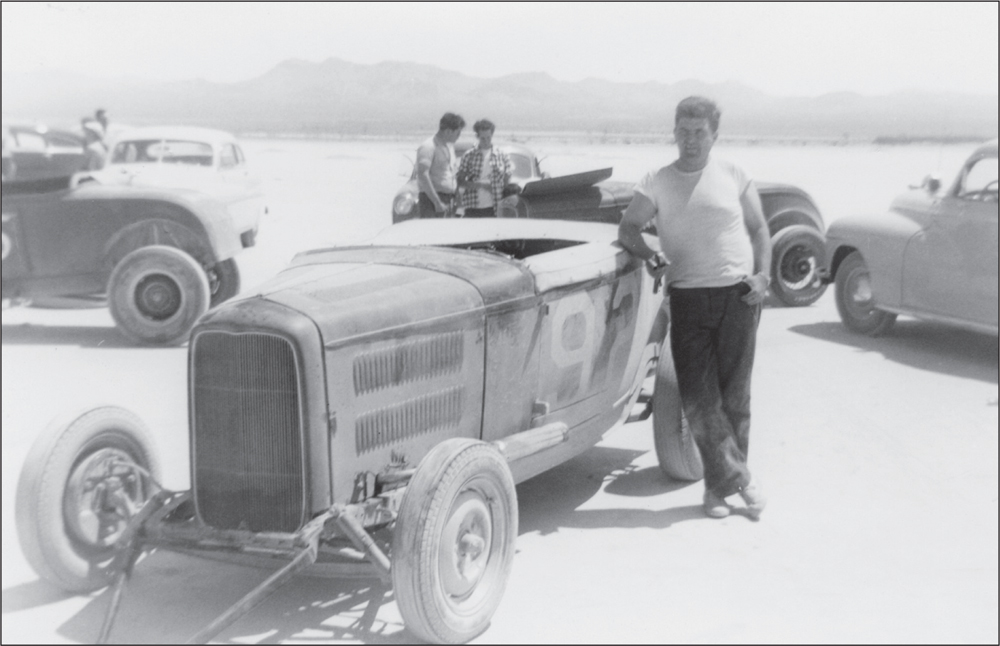

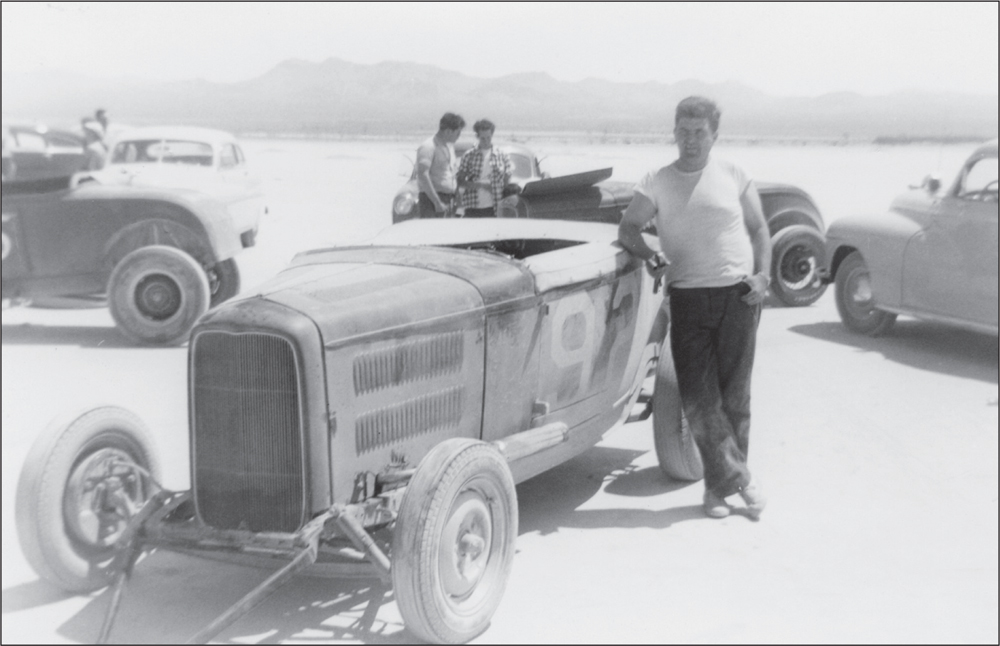

Because El Mirage was too small for the kind of speeds that racers were beginning to achieve, the action moved to the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah by 1951. Hot-rodders from all over the country began meeting there, and the guys from the Central Coast were no exception. Lee Hammock and Rip Erickson were there early on with this Wayne-GMC–powered 1934 Ford coupe. Erickson was able to get it up to 142 miles per hour on its speed run, but what is really interesting about this particular hot rod is its history. Built in Carpinteria by Ollie Olivas, it moved to Ventura for a while and was then bought by Jack Quinton. Quinton replaced the GMC engine with a flathead and sold it to hot rod writer Alex Xydias of Los Angeles. Under Xydias’s ownership, the car acquired a white paint job with red scallops and became one of the world-famous “SoCal Speed Shop” specials. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

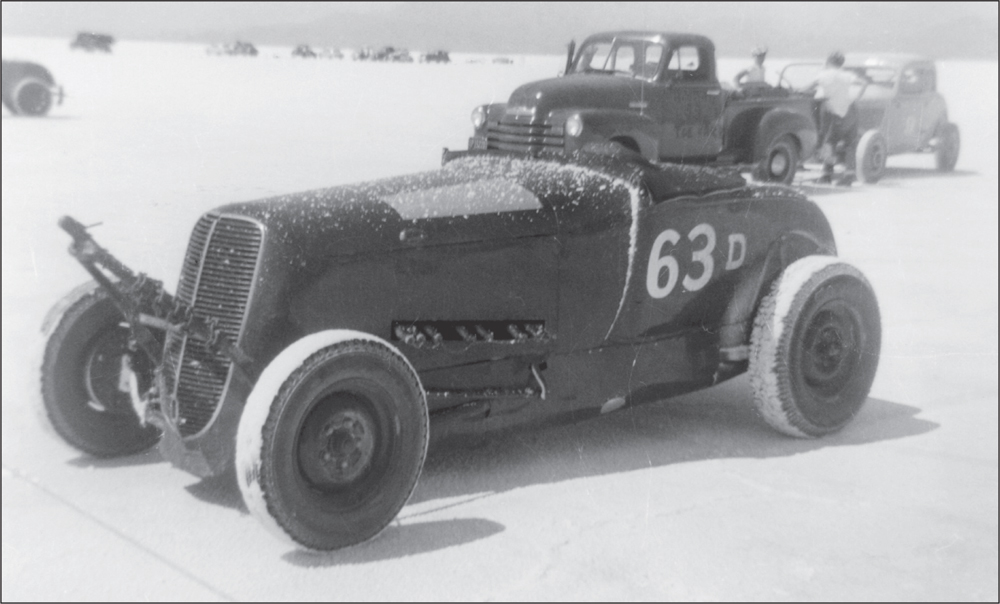

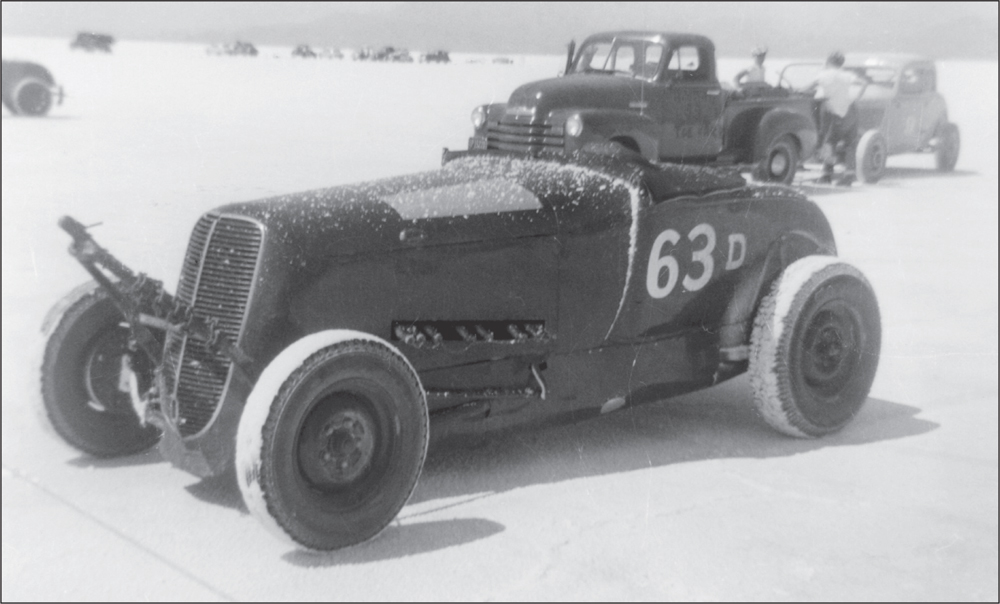

While at Bonneville, Lee Hammock snapped a picture of this 1929 Ford roadster. The grill shell might be from a mid-1930s Dodge or Chrysler, but what makes this one really unusual is the V-16 Marmon engine under the hood. Note the eight exhaust stacks coming out of one side. The tires are caked with salt from the lake bed, and there is a liberal sprinkling of it on the car’s body as well. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

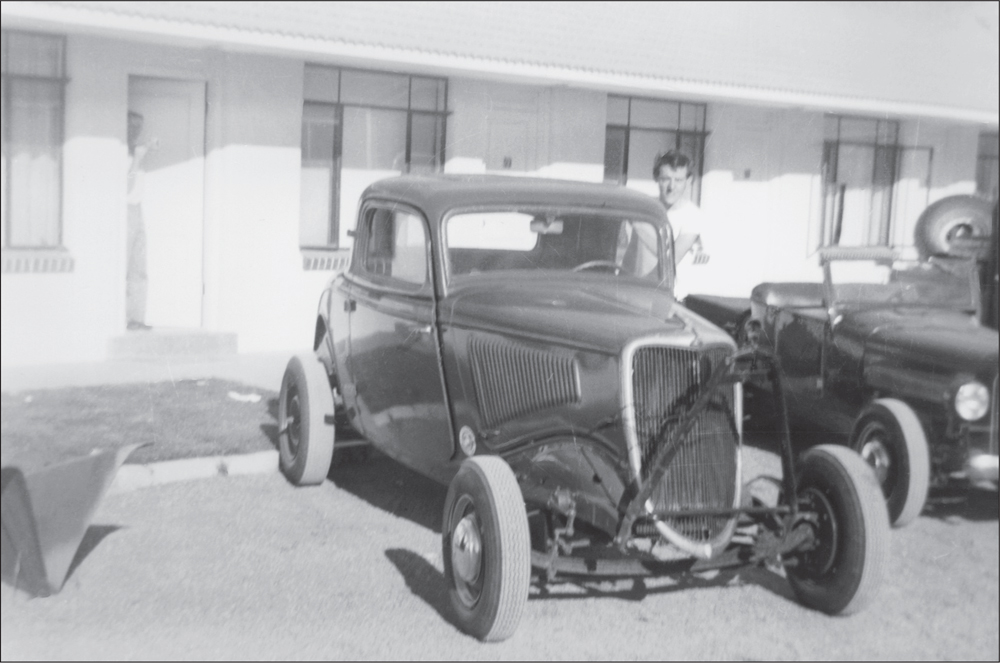

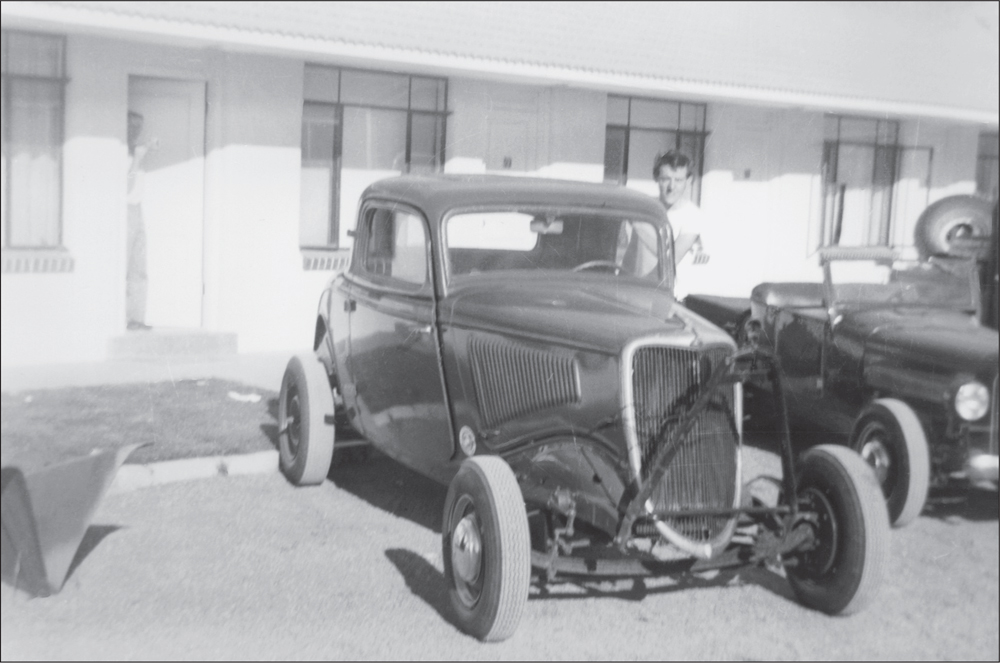

Another member of the Santa Barbara contingent at the salt flats was Jack Quinton, seen here with his hot rod in downtown Bonneville. Jack towed the metallic gold 1932 Ford coupe to Utah using his Mercury, visible on the left. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

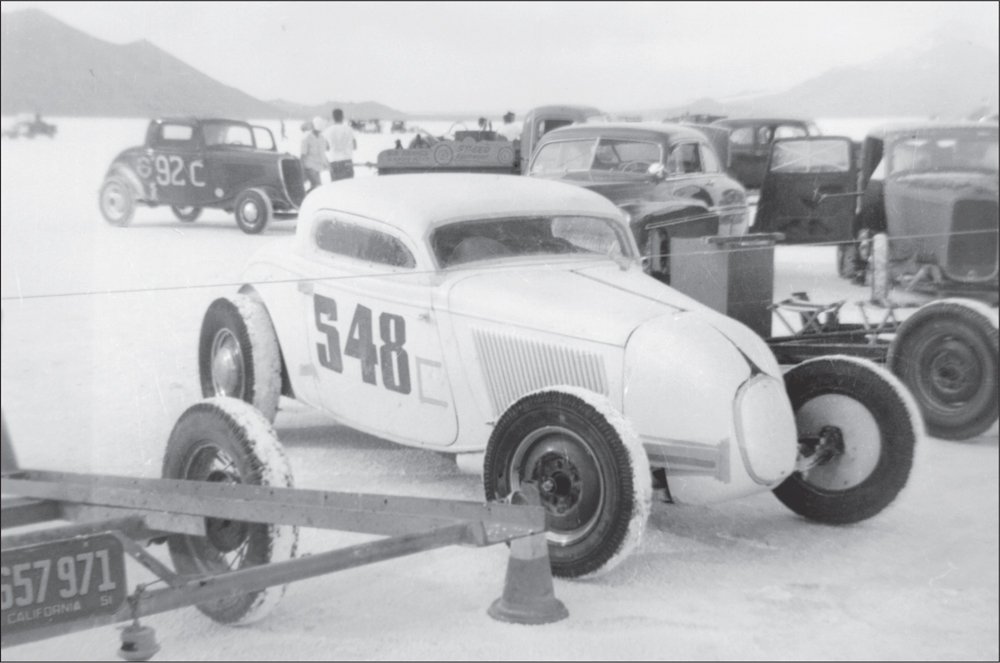

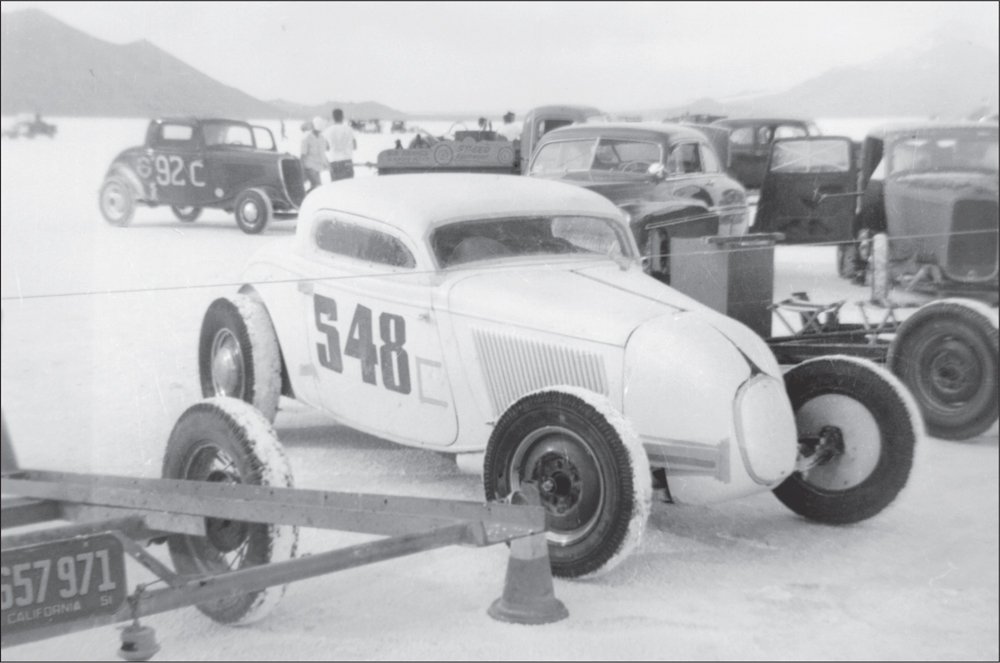

Jack Slickton of Santa Barbara towed his 1934 Ford coupe to Bonneville. The Model T roadster at right was driven all the way to Utah by a Santa Barbara hot-rodder remembered only by his nickname, “Just Plain Bill.” That is a Pontiac grill shell on the Model T. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)

A rear view of two virtually identical Deuce coupes seems like an appropriate way to end this pictorial history of hot rodding in Santa Barbara County. The story of how a group of Central Coast hot rod enthusiasts moved into a pair of abandoned air bases and helped create a national sport has been told here through their images and memories. Although the venues for seeing motor sports have diminished since the golden days of the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, there are still places on the coast where one can go to the races. And, despite the fact that hot rodding is well over a half century old, there seem to be more and bigger car shows each year, drawing bigger and bigger crowds. Perhaps it will never die out. (Courtesy of Lee Hammock.)