Article II section 2 of the United States Constitution establishes that the president nominates the justices of the Supreme Court as well as “all other Officers of the United States by and with the advice and consent of the Senate.” While there has been significant debate as to the meaning of “advice and consent” clearly it encompasses the right of the Senate to approve presidential nominations by a majority vote of the legislative body. The reason for this is argued by Alexander Hamilton, who wrote that Senate approval “would be an excellent check upon a spirit of favoritism in the President and . . . prevent the appointment of unfit characters” (Rossiter 1961, 457).

Article II section 2 also gives the executive the power to “fill up all Vacancies that may happen during the Recess of the Senate, by granting Commissions which shall expire at the End of their next Session.” The purpose of the Recess Appointment Clause is clear—it allows the executive to keep the operations of government running even when the Senate is not in session and thus is unable to confirm presidential appointees. However, this clause also appears to upset the pristine formulation (Pyser 2006) of separated powers by allowing the president to bypass the Senate and appoint judges without any oversight not to mention the lack of “advice and consent.”

While many scholars (Buck et al. 2005; Cardozo Law School Symposium 2005) have considered the propriety or constitutionality of recess appointments to the federal judiciary, in this chapter we seek to answer the simple yet intriguing questions of why and under what circumstances presidents use this recess appointment power. Given that most recess appointees are usually confirmed, why avoid an initial vote in the Senate to appoint a judge just for the remainder of the Congressional session? How does such a clause function in an age of instantaneous communication and speedy travel? We also address the question of whether presidential use of the recess appointment power has changed over time in response to changes in the relationship and power of governmental branches as well as changes in the nature and circumstances of Senate recesses. To answer these questions we examine all incidences of judicial recess appointments from George Washington in 1789 to George W. Bush in 2004.

These are important questions because the use of the recess power, like other unilateral powers vested with the president, can upset the carefully calculated separation of powers envisioned by the framers. In particular the abuse of this power can result in presidential favoritism or judges deemed “unfit” by a majority of senators. Two scholars of judicial appointments noted in a recent book that President Clinton’s recess appointment of Roger Gregory to the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit was the first recess appointment to the Judiciary since the presidency of Jimmy Carter in 1980 (Epstein and Segal, 2005, p. 81). Unlike most other unilateral presidential powers, judicial recess appointments are one of the few areas of politics that affect all three branches of government. They can shift power over the third branch away from the Congress and toward the executive branch.

In the ensuing chapter we explore under what political and institutional circumstances a president is likely to make a judicial recess appointment. While conventional wisdom holds that a politically weak president, lacking support in the Senate, is more likely to use the recess power to avoid the necessity of Senate approval, we find to the contrary in the modern era. We argue that politically strong presidents are more likely than weaker presidents to make judicial recess appointments. In a Separation of Powers system the recess appointment power allows a president to move the judiciary ideologically closer to his preferences, but this opportunity carries risks that political support can relieve. To demonstrate this we assess the literature on judicial appointments and judicial recess appointments. Next we offer a brief review of previous scholarship of presidential power. Then we present our data, methodology, and results of our study. Finally we offer our conclusions and suggestions for future research.

While there has been little examination by political scientists of judicial recess appointments, the nomination and confirmation process of the judiciary has received significant scholarly attention. As several recent and classic books on judicial appointments make clear, presidential appointments to the federal judiciary have always been a contentious process driven by political and ideological concerns, both at the Supreme Court (Abraham 1992; Yalof 1999; Epstein and Segal 2005) and for lower courts (Epstein and Segal 2005). Although there are other considerations such as geographical balance, racial, ethnic, and gender diversity, and senatorial courtesy, presidents have consistently used the appointment power to nominate judges who will rule in a manner ideologically consistent with the preferences of the nominating president (Abraham 1992; Yalof 1999; Segal, Timpone, and Howard 2000; Epstein and Segal 2005). Some prominent scholars argue that ideological and political considerations and politicization have particularly increased since the presidencies of Ronald Reagan and the first President George H.W. Bush (see, e.g., Goldman 1997).

Republican presidents overwhelmingly appoint Republican judges and Democratic presidents overwhelmingly appoint Democratic judges (Segal and Spaeth 1993), although at least for the Supreme Court, political party matters less than ideology (Epstein and Segal 2005). On the whole, presidents are remarkably successful in pushing through their nominees and in finding ideologically similar justices (Segal, Timpone, and Howard 2000), even if ideological concordance between judges and presidents varies from president to president, at least at the Supreme Court level. In short, a president seeks to increase his institutional power through the appointment process. In a Separation of Powers system an ideologically compatible judiciary is far more likely than not to support presidential preferences (see Yates and Whitford 1998).

In order to achieve the goal of moving the federal judiciary in the direction of his ideological preferences, presidents must make strategic choices for lower courts as well as at the Supreme Court level (Massie, Hansford, and Songer 2004; Moraski and Shipan 1999). The Senate’s constitutional role of providing “advice and consent” to permanent third branch appointments requires the president to choose nominees who can garner sufficient votes for confirmation, either a majority under ordinary circumstances, or filibuster-proof supermajorities under extraordinary conditions of conflict between the executive branch and the Senate minority, as observed recently.

However, presidents care about more than just eventual confirmation. Swift confirmation is also important. Several scholars have shown that delay rather than outright rejection is a key consideration for the president and a tool for those opposed to the appointment in the “advice and consent” confirmation process (Shipan and Shannon 2003; Binder and Maltzman 2002; Martinek, Kemper, and Van Winkle 2002; Nixon 2001). Delay is the great strategy of individual senators opposing the nominee (Bell 2002). Holding up the appointment can serve several goals for those opposing the nomination. A sufficiently significant enough delay can destroy the nomination or leave the president exposed as weak (Shipan and Shannon 2003; Nixon 2001). This can obstruct the president’s other legislative priorities. In addition, delay can hinder and deter the president from achieving policy goals by delaying the appointment of like-minded ideologically compatible justices. Scholars have found that delay appears likely in times of divided government and also in times of ideological polarization within the Senate and between the Senate and the president (McCarty and Razaghian 1999; Bell 2002; Shipan and Shannon 2003).

Nevertheless, appointments to the judiciary, unlike the executive branch, can long outlast an individual presidency. The value of avoiding delay is unlikely to be great enough to offset the cost of failing to permanently seat a federal judge. Judicial recess appointments, therefore, call for careful considerations if they are to be used strategically. If the Senate and the president are each seeking greater institutional power, judicial nominations become a key battleground in that process. Greater ideological compatibility between the courts and either branch of government gives the executive or the legislature a key ally in moving policy preferences into public policy.

Although judicial recess appointment has fallen into disuse in recent years (Buck et al. 2004) a few recent appointments such as those of Roger Gregory, William H. Pryor, Jr., and Charles Pickering have highlighted the practice and led to both public interest (Hurt 2004) and scholarly analysis (Cardozo Law School Symposium 2005). The recess appointment of William H. Pryor, Jr. by President George W. Bush resulted in a court challenge of the constitutionality of recess appointment to Article III judicial seats. Pryor’s confirmation stalled in the Senate when many interest groups objected to his views on various matters, leading to a filibuster by minority Democrats. With the nomination languishing in the United States Senate, Congress adjourned for twelve days in mid-February, 2004. During the congressional recess period President Bush used his recess appointment power to install Pryor as judge, bypassing the confirmation process in the U.S. Senate.

The Pryor appointment was challenged because the appointment was an intrasession recess appointment as opposed to an intersession recess appointment. The plaintiffs argued that a “recess” did not mean a relatively brief “intrasession” vacation or other temporary adjournment but rather referred to a longer formal “intersession” break, when there would be a significant need for government continuity and the administration of justice that would be severely hampered waiting for Congress to return. Eventually, in Evans v. Stephens (2004), a divided en banc Eleventh Circuit rejected the plaintiffs’ contentions and, with majority and dissenters differing on the plain meaning of the United States Constitution upheld the appointment of their colleague Judge Pryor. Following the decision, a bipartisan agreement then allowed Pryor’s nomination to be put to a vote and he was confirmed to a permanent seat on the Eleventh Circuit after sitting more than a year by recess appointment.

Given the prominence of the Pryor appointment and another judicial recess appointment by President George W. Bush in January 2004 of Charles W. Pickering Sr., whose nomination had previously been blocked twice in the Senate, scholars and jurists have recently devoted considerable attention to when and under what circumstances presidents should make recess appointments. However, there is nothing new about presidents using the recess appointment power to seat federal judges. George Washington appointed three judges to the Federal District Court during the recess of the First Congress. Fifteen Supreme Court justices have initially been seated through the recess appointment power, including Chief Justice Earl Warren and Associate Justices William Brennan and Potter Stewart, and presidents have made over three hundred recess appointments to the federal judiciary. Scholars have noted, however, the infrequent use of recess appointments to Article III judicial seats since President Kennedy. Judicial recess appointments are not innovative, untraditional uses of the president’s constitutional authority, but they are controversial and, within the context of modern congressional-executive relations, problematic.

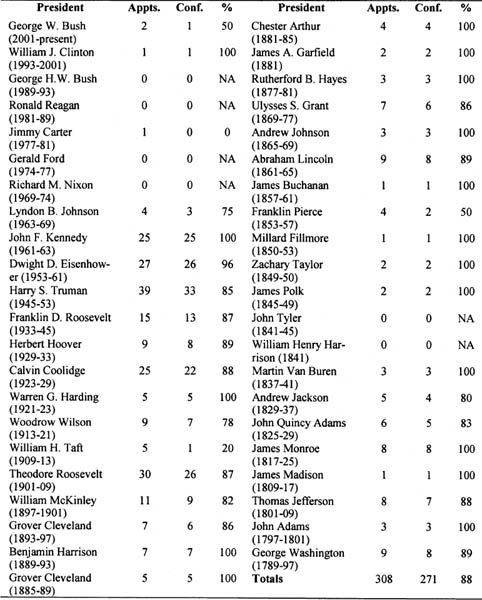

Table 2.1: Recess Appointments and Confirmation Percentages

Table 2.1 provides a list of all judicial recess appointments made by the presidents of the United States from George Washington through George W. Bush. The data show that, with some exceptions, presidents are remarkably successful in having their judicial recess appointments confirmed by the Senate. Of the 308 recess appointments in Table 2.1, 271, or 88 percent, were later confirmed to full terms as federal judges. With the exception of John Tyler and William Henry Harrison (who died in office after only thirty days) all presidents in the eighteenth and nineteenth century used the appointment power including George Washington who made nine recess appointments.1 The middle part of the twentieth century saw significant use, but its practice substantially declined from the presidency of Lyndon Johnson to the present with the recent exception of a few prominent, but controversial appointments described above.

Uses of the recess appointment power in recent decades have triggered substantial debate about the propriety and wisdom of the exercise of the recess appointment power. Following President Eisenhower’s third placement of a Supreme Court justice during a recess, the Senate passed a resolution (S. Res. 334) opposing the practice. The resolution stated that recess appointments to the Supreme Court should be used only “under unusual and urgent circumstances” and the corresponding report from the Judiciary Committee asserted that such appointments obstructed the Senate’s “solemn constitutional task” of providing advice and consent.2 Despite the institutional prerogatives asserted, however, the resolution passed on a primarily partisan vote, forty-eight to thirty-seven (Fisher 2005).

More recently, recess appointments have become the focus of further contention and negotiation between presidents and the Senate. Following several non-judicial uses of the recess appointment by President Ronald Reagan, including one to the independent Federal Reserve Board of Governors, then-Senate Minority Leader Robert Byrd placed a hold on seventy other pending nominations, “touching virtually every area of the executive branch,” according to the White House, as well as including federal judges (Fisher 2001, 11). Reagan’s standoff with Byrd ended with the development of procedures for recess appointments, including notice prior to the beginning of the recess.3 Violation of this agreement became one of the issues surrounding President Clinton’s controversial recess appointment of Roger Gregory to a seat on the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals. After the Democrats regained control of the Senate in the 1986 election, Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole (R-KS), a potential candidate for the presidency, raised the possibility of giving a recess appointment to Robert Bork in response to delay in Bork’s confirmation hearings, a suggestion dismissed by a Senate Democrat as “playing politics” (Walsh 1987). No president has made such an appointment to the Supreme Court since the Senate’s resolution discouraging it, but that episode and those during the Reagan and Clinton administrations demonstrate that although the Senate sees important institutional principles at stake in recess appointments, they are also perceived through the lens of partisan politics.

Of course, some presidents have used the recess appointment power more often than others. President Truman made the most appointments, 39, and confirmed 33 for a success rate of 87 percent. Theodore Roosevelt followed Truman with thirty appointments, twenty-six of whom were confirmed for an 87 percent success rate. Presidents Eisenhower (twenty-seven with twenty-six confirmed) and Kennedy (twenty-five, all confirmed) made extensive use of the recess appointment power and were very successful in having their appointments confirmed.

Several scholars (Carrier 1994; Cardozo Law School Symposium 2005; Pyser 2006) have noted that the recess appointment power was of obvious value in the eighteenth century when limited transportation and a part time Congress meant that the chief executive needed a mechanism to keep the operations of government functioning, including the judiciary. Congress used to adjourn for much longer periods of time, and it was technologically impossible to reconvene Congress in a short period of time. It was the very different nature of Congressional recesses that led to the challenge of Pryor’s intrasession recess appointment. However, with the Eleventh Circuit decision upholding the intrasession recess of William H. Pryor and previous decisions upholding the constitutionality of judicial recess appointments, it is clear that whatever the normative desirability of such appointments federal courts have upheld the recess appointment power. The issue then becomes why and under what circumstances presidents will use this power.

In contrast to the shared authority of appointment laid out by the conventional process, the recess appointment power vests the president with the ability to act unilaterally, without the consent of and possibly contrary to the advice of the Senate. Like other unilateral powers possessed by the president, the recess appointment power can be conceived of as a strategic tool employed by the executive to act when the legislative process stands in the way of his goals. More than other unilateral powers, a recess appointment can alter the balance of power between all three branches of government. That is, recess appointments can serve as a way for presidents to influence the exercise of judicial power separate from, if not indifferent to, the power to persuade the legislature. Alternatively, presidential powers may be used as a complement to legislative action, or at least with care due to the prerogatives of Congress, rather than as a substitute for traditional inter-branch relations.

Research on the use of executive orders has elaborated on these different conceptions of unilateral presidential power. Although some scholars have discovered evidence that executive orders are used strategically when legislative obstruction can be anticipated (Deering and Maltzman 1999; Mayer 1999), others have concluded that executive orders are used in coordination with successful legislative activity or in favorable political circumstances (Krause and Cohen 1997; Mayer 1999; Shull 1997). Also, several studies contend that developments entirely within the executive branch influence the use of executive orders (King and Ragsdale 1988; Krause and Cohen 2000). Marshall and Pacelle (2005) found that the production of executive orders responds differently to institutional and political circumstances across issue areas, while Krause and Cohen (2000) identified a shift in the effect of a variety of factors on executive orders across time periods. Specifically, they concluded that constraints from Congress had a stronger effect on the issuance of executive orders after the “institutionalized” presidency had developed fully. Earlier presidents’ use of executive orders was driven more by intra-institutional concerns, opportunities for presidential action, rather than constraints.

From these findings on executive orders, we draw our two specific queries. First, do presidents use recess appointments in a strategic, perhaps confrontational fashion in order to achieve policy goals they would not be able to achieve through the conventional appointment process? Second, has the use of recess appointments changed over time as presidential power and the length and nature of Senate recesses changed?

On its face, a recess appointment to an Article III court allows the president to fill a vacancy with a favored candidate quickly, without the obstruction or rejection the confirmation process might produce. Such appointments are temporary, but an intrasession recess commission can last for nearly two years, if the recess falls early in the congressional session (Carrier 1994). This allows the president to appoint an ideologically compatible judge to serve on an Article III court producing rulings that the president favors for a significant period of time. Little quantitative research has been conducted on recess appointments, but one study (Corley 2003) finds that the president is more likely to recess appoint an independent commissioner when the president is ideologically distant from the Senate and when the president’s approval ratings are low.4

Other considerations suggest that recess appointments may be used for reasons other than the advancement of purely political goals. As described above, when the Constitution was ratified and throughout the eighteenth century, the recess appointment power had clear justification due to the length of Senate recesses and the time-consuming nature of travel across the ever-expanding nation. Whittington and Carpenter note that the makeup of the executive branch predisposes the president to be motivated more by “efficiency, effectiveness, and national strength” compared to the legislature (2003, 498).

Also, as effective as a well-placed recess appointment to the federal judiciary could be, its immediate and long-term costs may outweigh or negate its short-term policy effectiveness. “When presidents have used temporary or recess appointments . . . to bypass the confirmation process,” Gerhardt notes, “senators have invariably used their other powers, particularly oversight and appropriations, to put pressure on those choices” (2000, 174). Furthermore, the ability of a president to extend his influence beyond his terms of office by reshaping the federal judiciary through life-term appointments is not served, and may be frustrated, by the injudicious use of unilateral authority like the recess appointment power. Thus, the use of recess appointments may have changed as a consequence of temporal or institutional changes. Recent controversies over recess appointments, especially to fill vacancies in the judicial branch, have raised the lack of compelling traditional justification for these appointments such as the unavailability of Congress for extended periods. To take a preliminary look at the relationship between judicial recess appointment practice and recess length, Figure 2.1 presents a graph of both series. Examining the average length of Senate recesses over time, we see a dramatic and enduring decline beginning at around the 90th Congress in the late 1960s. This decline coincides with the recent drop in the incidence of recess appointments to the federal bench, suggesting that the latter trend may be in large part due to the diminished justification for such appointments. We should expect that recess appointments will be less common in the absence of reasons for them. Moreover, those that do occur under such circumstances, we anticipate, may spring from more political or policy-based motives. Following Krause and Cohen (2000), we also suspect that changes in the nature of presidential power over time could have altered the relationships between various factors and the incidence of recess appointments.

The effect of time on the use of presidential powers can be conceived of in a variety of ways. Skowronek (1993), for example, distinguishes secular and political time. Secular time is related to the expansion of resources and responsibility. Skowronek then follows this time through four distinct presidential eras of the nation’s history and shows how the accumulation of power is dependent upon the uses of power appropriate to the particular era–patrician, partisan, pluralist, or plebiscitary.

Lewis and Strine (1996) describe four different conceptions of “presidential time”: secular, regime, modern, and political time. “Secular presidential time” as they describe it proposes that presidents have benefited from a monotonic increase in power since the beginning of the Republic. A “regime time” approach divides presidencies into a number of time periods. “Modern” presidential time contrasts the presidency before and after a transformation period. Lewis and Strine demarcate the beginning of the modern era with FDR.

Lewis and Strine analyze secular and regime time by “looking for broad trends in veto use over the 1890-1994 period” (690). The authors expected that the effect of a secular increase in presidential power over time will result in a steady decline in vetoes, but found no such pattern. Likewise, we observe no indication that recess appointments to the courts have either monotonically increased, or decreased, which would be the case if presidential power to reshape the judiciary through conventional appointments increased consistently.

Turning to regime time, Lewis and Strine admit that “[n]o explicit hypotheses exist to explain how presidents within regime cycles will use power” (1996, 687). Nevertheless, they sketch some expectations about veto use by various presidents at different points within regime time and test them by examining the differences in veto production across presidents from 1890 to 1994. They acknowledge that including presidents whose regime positions are uncertain or who seem atypical of their regime positions would “leave us with much murkier results” (1996, 698). The authors noted that presidents “may share similar positions in the regime cycle but their positions are fundamentally different because of the changes that have occurred in the presidency between the tenures of the two presidents” (1996, 697).

Conducting an event count analysis, Lewis and Strine find that use of the veto corresponds to their expectations of the modern/early conception of presidential power, but not with their predictions about political time. Of particular interest, they find a substantial shift in presidential power with the beginning of the modern presidency, especially with regard to the president’s legislative activity. Presidential power in modern time is not merely different in magnitude from the pre-FDR era; the nature of its use is different.

We note that the veto is similar to the recess appointment power in some ways—both are reactive to opportunity—but different in several important respects. A presidential veto is an answer to congressional action, typically a hostile one, while recess appointments are often a response to Senate inaction. Furthermore, a recess appointment stresses the president’s proposal advantages in a way vetoes do not. Because the president usually wants the Senate to confirm the person he has temporarily seated, the recess appointment can be thought of as an invitation rather than a rebuff.

Recess appointments share several qualities with the president’s authority to issue executive orders, discussed above. Many scholars have observed that executive orders tend to proliferate with increases in the president’s legislative strength and success (Krause and Cohen 1997; Mayer 1999). Not only can legislative support facilitate or increase the value of executive orders, using them as an end run around Congress carries substantial risk. As Cooper notes, “Clinton, Reagan, Carter, Nixon, and Johnson, among recent presidents, encountered significant difficulties . . . by challenging the legislature using executive orders” (2002, 71).

In order to get an initial idea of the coincidence of recess appointments per Senate recess and executive orders across time, Figure 2.2 plots these two series. Although not as overt as the relationship in Figure 2.1, the production of executive orders per presidential term appears to follow a distinct, non-monotonic secular trend, rising and falling with the advent of the administrative presidency. A vertical line marks the 72nd Congress, the final Congress before the Roosevelt era. In contrast to the stylized account of an ever-increasing administrative state and executive power, the figure indicates that after slight but consistent growth, executive orders rose abruptly preceding FDR, spiking during the Great Depression and WWII. After Roosevelt’s abbreviated last term and demobilization under Truman, the rate of executive order production appears to have settled back to a level not inconsistent with pre-twentieth century trends, but displaying considerably more volatility. The dispersion of recess appointments during and after FDR’s presidency is, if anything, slightly sparer than before.

For the purposes of this study, we take note of Lewis and Strine’s identification of a shift in the use of presidential power coinciding with the Roosevelt administration and the advent of the “modern” presidency. We expect that the use of judicial recess appointments in the “modern” presidential era will differ from the earlier era. Changes in the nature of presidential power, combined with the decline in previous, efficiency-based justifications for recess appointments, suggest that presidents in the modern era should be more careful with their use of this power and sensitive to the political costs of short-circuiting the traditional path of appointment through the Senate. Therefore, we believe that modern presidents will respond differently to the circumstances surrounding the opportunity to make a recess appointment than those in the earlier era.

Our study examines incidences of recess appointments in every Senate recess from 1789 to 2004 stretching from George Washington to the end of George W. Bush’s first term.5 Toward that end we collected data on these recesses, such as the length in days of each recess, and whether or not the recess was intersession, as identified by the Congressional Directory. From data collected by the Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy, we identified the number of recess appointments made to Article III courts in each of the recesses (Buck et al. 2004).6

Guided by theory and previous studies, we expect that several factors will affect the use of recess appointments to Article III courts. Presidents and the Senate have long contested the meaning of a “recess” for the purposes of Article II, Sec. 2. Even though the power of presidents to make such appointments during an intersession recess, following the sine die adjournment of a session of Congress, has not been contested, appointments during intrasession recesses have been both controversial and rare. Thus, we coded a variable for each recess identifying whether or not it was intrasession and anticipate that appointments during such recesses will be comparatively uncommon. We also calculated the length of the Senate recess, hypothesizing that longer recesses are more likely to produce lengthy vacancies that could impair the function of the judicial branch and prompt a recess appointment.

Despite the conventional wisdom that presidents rely on unilateral powers, especially the recess appointment power, when they are politically weak in the legislature, we are persuaded by the findings of the executive orders literature and expect that the strength of the president’s party in the Senate will make recess appointments more, rather than less, likely. Our explanation, however, is slightly different. Rather than using executive orders to build upon legislative successes, we believe that recess appointments are politically safer for the president when he has a strong partisan majority in the Senate to protect his legislative agenda from obstruction. This relationship should be especially strong in the “modern era,” after the expectation of executive involvement with the legislature strengthened. We measured the strength of the president’s party in the Senate during each recess in the dataset as the proportion of seats held at that time.

Another factor that we believe will influence the use of recess appointments is the value of the appointment itself. Although there are several ways to measure the value of a judicial appointment, one that lends itself particularly well to our aggregate data and the temporal nature of the recess appointment is the length of time the appointee will sit. The commissions issued to recess appointees expire at the end of the next session of Congress, which, in the case of an intersession recess, is the end of the next convening session. For intrasession recesses, however, the commission does not expire until the end of the following session, rather than the end of the session within which the recess falls. To capture these effects, we measure the length in days from the end of each recess until the end of the following session, taking into account the difference between inter- and intrasession recesses. We expect that the longer that period of time is, the longer the temporary commission will last, the greater the likelihood of a recess appointment.

The presidency literature suggests that presidential powers, even discretionary powers like executive orders, are used with sensitivity to the Congress and the agenda of the president. We hypothesize that recess appointments to the judiciary will be related to the use of the other major discretionary, self-initiated presidential power, the executive order, but in a time-bound way. Prior to the modern era, before the institutionalization of the executive office, we anticipate that executive orders will be positively related to recess appointments, as both are driven more by opportunity and intra-branch concern for efficiency, the “energetic” characteristics of the early presidency. A president who governs substantially by executive order is also more likely to use recess appointments.

In the modern era, however, efficiency concerns borne of legislative recess are less pressing while the expectation of executive involvement with the legislature has increased. As judicial recess appointments become more difficult to justify in traditional terms, opportunistic uses could jeopardize the president’s relationship with the Senate, delaying or derailing other appointments or legislative initiatives. Therefore, we hypothesize that modern presidents will use recess appointments, for want of a better word, judiciously, balancing their executive lawmaking authority and unilateral appointment power to avoid too many confrontations with Congress. Under such circumstances, we expect a negative relationship between executive orders and recess appointments. To test that relationship, we collected the number of executive orders issued by the presidential administration in which each recess fell.

We have differing sets of hypotheses for various factors across the early/modern time divide. Therefore, we included a variable to indicate whether or not the recess occurred before or after the beginning of the first FDR presidency. We also produced multiplicative interactions of several variables with the indicator for the modern presidency, including the president’s party strength in the Senate, the length of time until the end of the next session, and the number of executive orders. We also include several variables as controls. We collected the number of authorized judicial seats at the time of each recess to account for the varying number of opportunities present over time. Also, to test the conventional account of recess appointments, we coded a variable to indicate whether the Senate and president were held by different parties at the time of the recess. If recess appointments are used primarily to circumvent Senate intransigence, we should expect that the likelihood of observing recess appointments should increase when the branches are so divided.

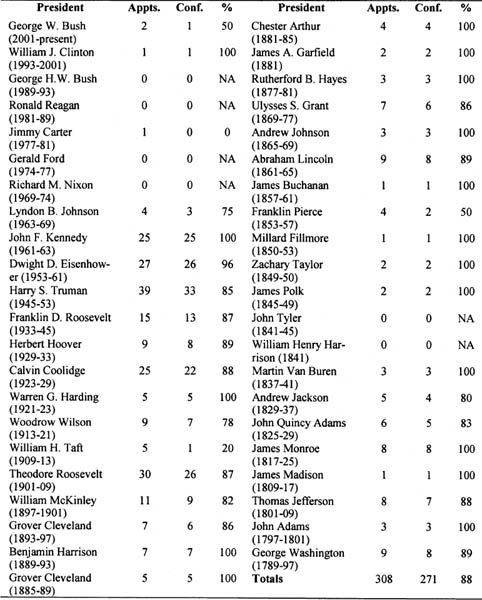

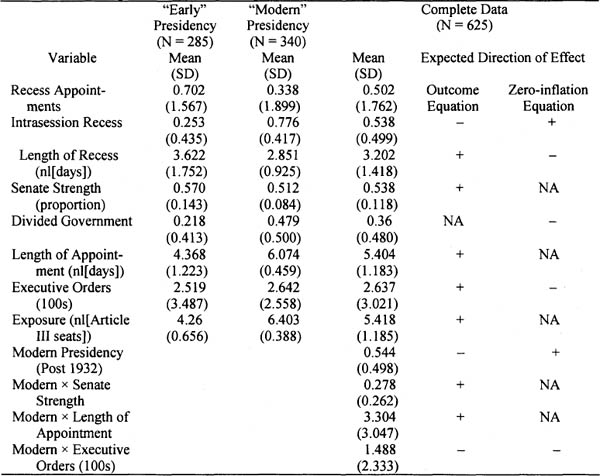

In order to control for the monotonic increase in the number of federal circuit court judicial seats over time, increasing the number of positions to be filled, we include the natural log of the number of authorized Article III judges. The anticipated direction of its effect is positive; as the number of judicial positions increases, the number of opportunities to make recess appointments will rise. In event count analysis, a variable of this nature is often referred to as an “exposure” effect (Cameron and Trivedi 1998, 81). Our data are summarized in Table 2.2. The expected effects for the Zero-Inflation Equation reflect the expected relationship between changes in the variable and the likelihood of being in the “zero only” state, so positive parameters indicate a direct relationship between the variable and observing no recess appointments during the recess in question. One of the first things to note about the data is the distribution of the dependent variable. The number of recess appointments made in a given recess is a discrete, non-negative outcome that ranges, in practice, from zero to twenty-three. The mean, however, is less than .5 for the entire dataset and the standard deviation is below two. Table 2.3 presents the frequency distribution of the variable. The distribution is dominated by zeros; over 80 percent of recesses have no recess appointments. The remaining distribution of non-zero observations also skews low, with 97.5 percent of the cumulative distribution (and over 80 percent of the non-zero observations) at four recess appointments or below.

Table 2.2: Descriptive Statistics and Expected Relationships, Senate Recesses

The standard method for discrete, non-zero count outcomes, the Poisson regression model common to veto and executive order studies, makes the restrictive assumption of equidisperion. That is, that the conditional mean and variance of the dependent variable are equal (Cameron and Triveldi 1998, 21). In fact, the observed variance of our outcome is more than six times its mean. Although excess zeros will cause overdispersion and overdispersion can result in excess zeros, the distribution of the dependent variable suggests that both problems exist independently. Even excluding the zero counts from our data, the variance of the dependent variable is nearly four times the mean of the remaining observations.

Table 2.3: Frequency Distribution of Recess Appointments by Recess, 1789-2005

To address both of these problems, we estimate a zero-inflated negative binomial regression model.7 Under our specification, the observed data is the result of a process that produces zero recess appointments with some probability, parameterized with covariates as a logit equation, and another process that produces a non-negative count of recess appointments following a negative binomial distribution.

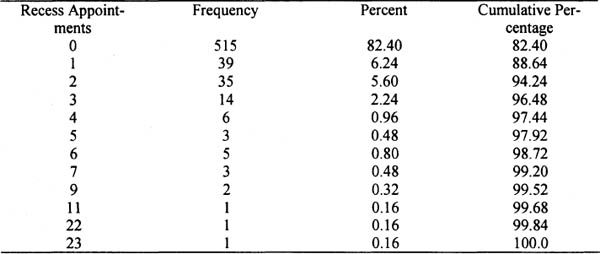

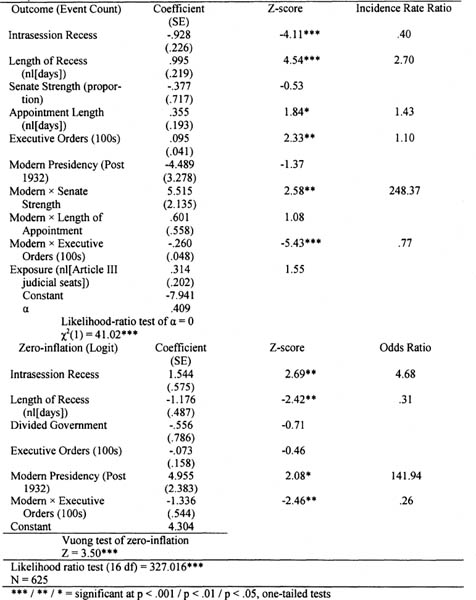

The results of the zero-inflated negative binomial model are presented in Table 2.4. The standard errors for the ZINB model are robust, clustered on the president. A likelihood ratio test of the variance factor a rejects the null of equidispersion and an adaptation of the Normally-distributed Vuong test for non-nested models applied to the zero-inflation equation rejects the null of no significant zero-inflation at an alpha of .001. Many of the hypothesized effects receive support as well. Intrasession recesses are significantly related to a decrease in the number of recess appointments observed and directly related to the production of zero-count recesses.8 The length of Senate recesses9 likewise has a consistent effect on recess appointments, decreasing the likelihood of observing a zero-state and increasing the conditional mean of the outcome.

The potential value of the recess appointment is significant and positive. This means that presidents are likely to produce more recess appointments as the length of time that appointees will sit grows. Interestingly, although the coefficient for the interaction of this variable with the modern era is positive, it is not statistically different from zero. It appears that this strategic use of recess appointments is invariant across time periods. The coefficient for the strength of the president’s party in the Senate is not significantly different from zero, but interacting it with the modern era dummy produces a significant and positive coefficient. This indicates that during the modern era, a rise in the proportion of the Senate controlled by the president’s party results in an increase in the expected number of recess appointments.

Table 2.4: Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial Model of Recess Appointments per Senate Recess, 1789-2004

The estimated relationship of executive orders to recess appointments is complicated. The constituent term is unrelated to the probability of being in the zero-state, but its coefficient is positive in the negative binomial equation. Thus, an increase in the number of executive orders issued during the current administration of the president in office during the recess increases the expected number of recess appointments. However, the interaction terms of executive orders with the modern era are significant in both equations. Modern presidents who produce more executive orders are significantly more likely not to make a recess appointment.

Several other results are worth noting. Cursory review of the summary statistics reveals that judicial recess appointments have been less common during the modern era, both in absolute numbers and per recess. The dummy variable for the modern era produces a significant and positive coefficient, indicating that recesses in the modern era are more likely, all else equal, to be in the zero-appointment state. The divided government variable, entered in the zero-inflation equation, is negative, as expected if divided government makes the use of the recess appointment power more likely, but not statistically distinguishable from zero. The variable controlling for exposure, the natural log of the number of Article III judgeships authorized at the time of the recess, is positive but insignificant in the negative binomial equation. This result is not entirely unexpected, as growth in the size of the federal judiciary has coincided with a decline in recess appointments. We conclude from this finding, however, that “opportunities” for recess appointments should be understood not in terms of the number of potential vacancies to be filled, but in terms of the conditions favoring such an appointment, which have become rarer even as the federal bench expanded.

Because event count models are nonlinear, we present transformations of the estimated coefficients in the fourth column of Table 2.4. For the negative binomial equation, we include the incidence rate ratio for each significant coefficient, which reflects the factor change in the expected count for a unit change in the variable in question, other variables held constant. An intrasession recess has a substantial impact on the expected count of recess appointments, reducing it by more than 60 percent. A unit change10 in the length of the recess is estimated to have the effect of increasing the expected count by more than a factor of 2.7. The standard deviation of the variable is greater than one, so an increase of one standard deviation has an even greater effect (4.1).

An increase in the length of the recess appointment itself produces a factor change of 1.43 on the expected outcome for one unit, but a standard deviation increase produces a 1.52 factor change. The incidence rate ratio of Senate strength in the modern era is 248.4, but since the variable never observes a unit change (which could happen only if the president’s party increased its seat share in the Senate from zero to one hundred) a more useful comparison is the factor change for an increase in one standard deviation, which is 4.24.

Interpretation of the impact of executive orders is also complex. The incidence rate ratio of executive orders (measured in hundreds) is 1.10, a modest 10 percent increase in the expected count for a unit increase in executive orders, but during the modern era that effect is coupled with a .77 rate ratio, producing approximately a .85 rate ratio for the combined impact. The standard deviation of executive orders is greater than 3, and the factor change for an increase of one such deviation is 1.33, but again the effect is counteracted by a 6.25 factor change for recesses in the modern era.

Turning to the zero-inflation equation, Table 2.4 presents odds ratios, which have an interpretation similar to incidence rate ratios for count models. The odds ratio represents the change in the odds of a positive outcome (in this case, the likelihood that the recess is in the zero-state) for a unit increase in the variable. An intrasession recess is considerably more likely to be in a zero-only state, nearly 4.7 times as likely, as an intersession recess. An increase in the length of the recess, however, makes the zero-state less likely by a factor of .3 for a unit increase or by .19 for a change of one standard deviation. Recesses occurring in the modern era, most of which are intrasession and brief, are far more likely to be in the zero-state. All else equal, a recess is about 141 times as likely to produce zero recess appointments during or after the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt. Finally, a unit change in the number of executive orders in the modern era produces a factor change of .26, over a 70 percent decrease in the likelihood of being in the zero-state. A standard deviation increase carries a factor change of about .05, or a 95 percent decrease in the same likelihood.

The findings of this analysis echo many of the conclusions of other studies of presidential authority. We discover that presidents are conditionally strategic in their use of the unilateral authority to appoint federal court judges during Senate recesses, but that the use of this power is careful and spare, especially in the modern era. Our results conform to what we believe to be the canonical uses anticipated when the power was extended. As efficiency justifications have declined, so have incidences of recess appointments, and the length of Senate recess has a significant and substantial effect on recess appointments. The estimated relationship between the length of Senate recesses and the incidence of recess appointments bears out the striking connection visible in Figure 2.1 and suggests that the rarity of such appointments in recent decades is in part an ordinary function of a change in Senate business.

However, this is not the only story. We also uncover evidence of strategic and opportunistic presidential use of the recess appointment. The length of time an appointee will sit has a significant, positive impact, and active presidents, measured by the number of executive orders issued, are more likely to produce recess appointments, but albeit fewer in number. We identify a change in recess appointments unconnected to the developments in congressional sessions. Consistent with the advent of a modern institutionalized presidency that engages considerably with the legislature, but is consequently tied to a substantial legislative agenda, we find that recent presidents balance their exercise of unilateral powers and use strong partisan majorities to shield themselves from the consequences of dispensing with advice and consent. Recess appointments that appear to be made at the expense of political capital and attention to other domestic policy initiatives bear the hallmarks of political or policy-motivated action, rather than the efficiency-oriented use contemplated for recess appointments.

In that context, the recent recess appointments of President Bush are somewhat atypical, made as they were when the Republican Party held a bare majority in the Senate. The remarkable party discipline exercised by the GOP, which has also allowed him to veto merely one bill in over five years (as of October 2006), might help explain the anomaly. In contrast, the Justice Department’s dismissal of eight U.S. attorneys to be replaced by never-expiring interim appointees without Senate oversight in late 2006 has, with Democrats now in control of Congress, prompted hearings in both Houses and the resignation of the Justice Department official personally responsible for the dismissals (Johnston 2007).

President Clinton’s appointment of Roger Gregory, made when the Democrats were a minority in the Senate, was also atypical in these terms. Clinton’s appointment was perhaps even more unusual because Gregory was eventually confirmed to a life appointment after renomination by his successor, although the Democrats had narrowly regained control of the Senate by that time. However, given that Clinton upset a long-standing understanding between the executive and legislative branches on recess appointments it is arguably a very strategic use of the recess appointment power and one that led to Gregory’s confirmation.

Our results suggest that contemporary use of the recess appointment power to fill federal judicial seats should be greeted with skepticism. Republican Senators Trent Lott and James Inhofe spoke vehemently against Gregory’s appointment and President George W. Bush’s appointments were met with similar condemnation from Democratic Senators. Gregory and Pickering’s recess appointments were both made intersession, abiding by the narrower understanding of the recess appointments clause favored by many senators and representing the shortest duration for recess commissions. However, Clinton appointed Gregory during a recess that lasted less than three weeks and Pickering’s appointment was made during one of the longest Senate recesses in recent years, just over five weeks. Given their observed sensitivity to the length an appointee will sit and other indicators that modern presidents make recess appointments in an opportunistic fashion, combined with the legal and political controversy surrounding them, we believe that judicial recess appointments are unjustified.

The unavailability of data back to the beginning of the Republic make it impossible to include ideological distance measures between the president and Senate, approval scores, and other useful factors in our analysis. The difficulty of disaggregating appointment data over such a lengthy period also limits our analysis. Closer study of judicial recess appointments confined to the modern era could take into account these additional factors and possibly find other ways in which the exercise of unilateral presidential power has been complicated since the institutionalization of the American presidency.

1. Controversies over judicial recess appointments are not an entirely new phenomenon. One of President Washington’s recess appointments was of John Rutledge to Chief Justice of the United States, igniting a controversy, which, according to Curtis (1984, 1775-6) contributed to his rejection by the Senate.

2. 106 Cong. Rec. 12761 (1960); S. Rept. No. 1893, 86th Cong., 2nd Session 1-2 (1960).

3. Ironically, a requirement that the President notify the Senate before a recess in which he intends to make a recess appointment makes impossible an initial interpretation of Art II Sec 2, favored by proponents of strong legislative oversight, which limited the president to temporary appointments only to fill vacancies that come into being during a Senate recess (Fisher 2001).

4. However, the same study concludes that a nominee from a different party than the Senate majority is not more likely to be recess appointed.

5. Excluding the recesses from 2005 to the present becomes necessary because the number of executive orders produced in President Bush’s second term is not known. As of November, 2007, no additional judicial recess appointments have been made after 2004.

6. Using the Senate recess as the unit of analysis is preferable for a number of reasons. Alternatives, such as aggregating to the year, congressional session, or presidential term would mean discarding valuable variation, especially since we have expectations about the likelihood of a recess appointment given the length of the individual recess, its temporal position in the session, etc. However, collapsing the data to the congressional session, including intersession recesses with the previous session, since the commissions share the same expiration date, the results for the remaining session-level variables are substantially unchanged.

7. This model deals with overdispersion, the greater than expected variation evident in the data, by modifying the conditional mean and variance functions and specifies a separate data generating process for some of the observed zero counts.

8. Coefficients in the zero-inflation equation have a somewhat counter-intuitive interpretation. The coefficients represent the estimates of a logit equation on the production of zero-count recesses, so a positive coefficient reflects an increase in the likelihood of observing a recess in the “zero-state.” Likewise, a negative coefficient indicates that the variable in question is inversely related to the observation of recesses in the zero-state. Other alternative specifications, such as including interactions of all the variables in the outcome and inflation equations with the modern presidency and including the exposure covariate in the inflation equation, produced substantively similar results although the former approach produced signs of convergence problems. Also, we re-estimated the model excluding the Truman and Kennedy outlier recesses featuring 23 and 22 recess appointments respectively as a sensitivity check. The results produced only one substantive difference: the intra-session recesses variable in the count outcome equation was no longer statistically significant at an alpha=.05 level (one-tailed).

9. Length of Senate recess enters the equation logged (ln[days Senate is in recess]) to account for the likelihood of a nonlinear effect. Using the raw number of days the Senate is in recess produces very similar results, but an inferior model in terms of log likelihood and information criteria.

10. The length of recesses enters the model logged, so an increase of one unit from the average Senate recess length represents a change from about 25 days to about 67 days and a unit decrease is down to 9 days.