In this chapter, we examine the influence of recess appointments and judicial independence on appellate court judicial voting. We also explore this issue through the lens of separation of powers and judicial choice by studying appellate court judicial recess appointees who have later been confirmed by the Senate to full time Article III judicial positions. Following our analysis in Chapter Three, our strategy is to compare the votes of fourteen recess appointed judges of the U.S. Courts of Appeals during their temporary recess tenure with votes cast during a similar period immediately following Senate confirmation.

There are several reasons to address the recess behavior of Supreme Court justices and appellate court appointees separately. From nomination through confirmation, to the structures of the courts, docketing procedures, and voting practices, the United States Courts of Appeals and the Supreme Court are very different. First the Supreme Court is the only court explicitly created by Article III of the United States Constitution. All other courts, including the Courts of Appeals, are creations of Congress via statute. The outline for the appellate courts’ present organization was not set in place until March 3, 1891, with the passage of the Everts Act, creating the Circuit Courts of Appeals. Congress changed the name to the Courts of Appeals with the Judicial Code of 1948. Initially, the Circuit Courts of Appeals were composed of nine regional courts, although the District of Columbia was added soon after in 1893. The Tenth Circuit was carved from the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals by an Act of 1929, and in 1981 the Eleventh circuit was created by splitting the Fifth Circuit. In 1982 a specialized appellate court, the Federal Circuit, was created from the old Court of Claims and Court of Customs and Patents. As of 2006, there were 179 authorized courts of appeals judges.

The nomination process for appellate court judges is also quite different. Supreme Court nominations are handled by the White House, whereas lower court nominations must deal with the norm of Senate courtesy that is deference to the home state senator’s interest in the nominee. While courtesy is not as important in the selection of Courts of Appeals nominees as it is for District Court nominees because Courts of Appeals cover several states, individual seats are usually identified with particular states, giving the home state senator some influence over the nomination (Giles, Hettinger, and Pepper 2001; Slotnick 2002).

The United States Supreme Court now has almost total control over its docket. For much of the twentieth century, the justices alone have chosen the cases they will hear and decide. This means that almost all of their votes are on significant cases and often on issues that are politically and ideologically polarized. In contrast the Courts of Appeal have mandatory dockets. Their cases frequently inspire little or no basis for legal or factual disagreement. In addition, the Supreme Court hears cases as a whole, whereas the vast majority of cases that Courts of Appeal judges hear are in rotating three judge panels. Rarely does an appellate court sit en banc.

The cultures of the Supreme Court and the Courts of Appeals are also quite different. Supreme Court justices are assumed to have no further ambition, having reached the top of the judicial hierarchy (Segal and Spaeth 1993). They usually work in isolation and there have been well-known instances of bitterness among the members. Justice McReynolds, for example, was well known to be anti-Semitic and refused to talk to Justice Brandeis and Justice Cardozo, the two Jewish members of the Supreme Court at that time (Pride 1996). McReynolds also made his disdain for Justice Stone well known. In contrast, the Courts of Appeals are known for their collegiality (Hettinger et al. 2006). This contributes further to the remarkable level of consensus and unanimity on these courts.

Thus, we offer separate comparisons of the recess and post-confirmation voting of judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals in this chapter. Simply put, do these appellate court recess appointees vote differently during their temporary tenure than they do after securing Senate confirmation? Are the complaints of litigants and the fears of court observers that diminishing the constitutional protections of judges’ independence compromises the exercise of judicial power justified?

Few would disagree that there is an element of strategic thinking in the vote choices of Article III Appellate Court justices. Even though a federal judge is given lifetime tenure, evidence demonstrates that the threat of congressional retaliation against the institution can constrain the choices of a judge (Cross and Nelson 2001, 1460-1473). A recess-appointed judge is in a far more precarious position. A recess appointee has no guarantee of lifetime tenure and confronts a very real threat of removal from the bench with the sitting of the next Congress.

The purpose of the Article III protections of judicial independence is clear—they ensure that the judicial branch is not subject to the inappropriate influence of other interests. As Hamilton explained in Federalist 78:

Periodical appointments, however regulated, or by whosoever made, would, in some way or other, be fatal to [the courts’] necessary independence. If the power of making them was committed either to the executive or legislature, there would be danger of an improper complaisance to the branch which possessed it; if to both, there would be an unwillingness to hazard the displeasure of either. (Rossiter 1961, 471)

The purpose of the Recess Appointment Clause is also clear—it allows the executive to keep the operations of government running even when the Senate is not in session and thus is unable to confirm presidential nominees, including judicial nominees. Along with the important value of judicial independence, the Recess Appointments Clause reflects the founders’ commitment to continuity in government. Presidents now use the recess power even if Congress has a relatively brief intra-session break, however. As we have discussed, President George W. Bush appointed William Pryor to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals during a twelve-day mid-winter break by the Congress, while in the last days of his presidency Bill Clinton named Roger Gregory as the first African American on the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals during a 20-day inter-session recess. It is a separation of powers game that pits the executive appointment power against the right of the Senate to offer advice and consent. The fact that Gregory, whose seat had gone unfilled for a decade despite several nominations over the entirety of the Clinton presidency, was eventually renominated by Clinton’s opposite-party successor and confirmed by a Republican-controlled Senate demonstrates the subtle power of the status quo established by a recess appointment.

Judicial recess appointments, unlike those to executive positions, affect all three branches of government. While the recess clause can shift power over courts towards the president and away from Congress it can also affect the exercise of judicial power. If someone is placed on the court by recess appointment, that person might measure his decisions against the knowledge that the Senate Judiciary Committee could later question those rulings. Moreover, there is the argument that the Constitution guarantees litigants a hearing before judges enjoying the full protections of the Article III tenure and salary provisions.

The Supreme Court has recognized the importance of the Article III guarantees to the legitimate exercise of the judicial power of the United States. In Northern Pipeline Co. v. Marathon Pipe Line Co. (1982), the Court invalidated the Bankruptcy Act of 1978, concluding that Congress had impermissibly conferred judicial power onto courts that did not enjoy the protections of Article III. After subsequent revisions by Congress, bankruptcy judges serving fourteen-year terms can conduct proceedings, but their findings of fact and conclusions of law must be submitted to the district courts and both are subject to de novo review by Article III judges.

In addition, since recess appointees weaken the advice and consent role of the Senate, they arguably diminish the constitutional protections accorded to litigants. In short, a judicial recess appointment can damage judicial independence. Recess appointments to the executive branch of government generally do not pose this potential to undermine such a normatively important institution.

Judicial independence is an essential component of our legal system. Its goal is impartial, “law-based” decision making by judges, decisions made without regard for the political preferences of members of the other branches. “The judiciary,” Gerald Rosenberg writes, “is independent to the extent its decisionmaking is free from domination by the preferences of elected officials” (1992, 371). Others define judicial independence as “a condition in which judges are entirely free from negative consequences for their decisions on the bench” (Baum 2003) or “the ability of the individual judge to make decisions based on the facts and the law without undue influence or interference” (Zemans 1999, 628).

Unpopular decisions have led to calls for greater political control over the judiciary in recent decades, leading to a debate over the proper balance between judicial independence and accountability. Not long ago, United States District Court Judge Harold Baer generated both a suggestion from the president that he consider resigning and a call for his impeachment from a presidential candidate when the judge granted a suppression motion. In response, Chief Judge John O. Newman of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals and three former chief judges issued a joint statement, asserting that “when a judge is threatened with a call for resignation or impeachment because of disagreement with a ruling, the entire process of orderly resolution of legal disputes is undermined” (Zemans 1999, 626).

In part, judicial independence is a function of institutional structure. The Constitution creates a federal judiciary as a separate and co-equal branch, a branch given the power of judicial review. Article III of the United States Constitution preserves the independence of judges in their decision-making process by guaranteeing a lifetime appointment and salaries that may not be diminished. In theory, this independence, plus the power of judicial review, allows the judiciary to “stand as the ultimate guardians of our fundamental rights” (Horsky 1958, 1111). Thus, judicial independence allows judges to uphold minority rights when they are under attack. The responsibility of the individual judge is to adhere to the definition of those rights as identified by the institutions of the judiciary. However, Ferejohn (1999) suggests that the independence of the judiciary is threatened if Congress and the president are ideologically unified and the judiciary is comprised of judges with a different ideology.

In the United States the other branches have control over jurisdiction, court creation, appointment, enforcement of court rulings, appropriations for the operation of the courts, and can impeach judges. Thus, there are many ways in which Congress and the president can exert influence over the federal judiciary. For example, Congress has adopted legislation restricting judicial review of habeas corpus petitions, sentencing guidelines that include mandatory minimums severely limiting judicial discretion, and the Civil Justice Reform Act of 1990 imposing oversight by district level committees and mandating alternative resolution programs (See Zemans 1999).

Thus, the process by which judges are appointed and retained can have an impact on judicial independence and accountability. When presidents and senators subject judicial nominees to ideological “litmus tests,” they are routinely accused of undermining the nominees’ independence, while the presidents and senators assert that asking about a nominee’s “judicial philosophy” is a way to gauge whether the nominees are acceptable (See Geyh 2003).

Similar patterns exist for recess appointees. Jefferson B. Fordham, dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School, remarked that a recess appointee “is serving under the overhang of Senate consideration of a nomination, which is not in harmony with the constitutional policy of judiciary independence” (106 Cong. Rec. 18131 (1960)). The Senate, of course, is not the only actor the recess-appointed judge might have to please. In a report written for the Congressional Research Service, Fisher (2005) observes that “(a) recess judge might also have to keep one eye out for the reaction of the White House, which would review decisions issued during the recess period to determine whether they justified nomination of the judge to a lifetime appointment.” Such concerns led the House Judiciary Committee to issue a report in 1959 questioning the independence of judges sitting via recess appointment from political influence (Report 1959).

Herz (2005) employs an analogy to illustrate the difference between the situation of a judge sitting temporarily via recess appointment and that of a judge holding permanent commission. “These circumstances” he argues, “put the recess appointee in something of the same position as a law professor on a ‘look-see visit’; his or her job becomes one extended interview. These circumstances are utterly at odds with the commitment to judicial independence reflected in Article III’s good behavior clause and salary protections” (Herz 2005, 450).

While recess appointed judges will not have to confront the electorate, existing research on court nominations, judicial behavior, and judicial voting provides insight that buttresses the assertion noted above. Assuming that a recess appointee wants confirmation, the “electorate” that the nominee would care about most is the Senate. Research has shown that the median ideology of the Senate (Moraski and Shipan 1998) or even the partisan makeup of the Senate (Epstein and Segal 2005) can be critical to confirmation of the nominee as the president and Senate clash over the nominee each seeking an ideological advantage in the separation of powers struggles (Yates and Whitford 1998). The more liberal or Democratic the Senate the greater is the likelihood that the recess appointee would vote in a liberal direction.

Ideological voting is not the only way a recess-appointed justice could assuage Senate concerns. He would also likely avoid controversial rulings or behavior that would lead to unwanted attention. This could include avoiding separate opinion writing or making controversial votes, such as overturning precedent or state or federal law, or ruling against the state or federal government. Also, a judge may avoid liberal decisions dealing with high-profile issues that could mobilize political opposition, such as in cases dealing with civil liberties or rights claims.

Recent studies confirm some of these suspicions. For example, research on appellate court behavior shows that district court judges sitting by designation on the appellate court are less likely to issue separate opinions or otherwise engage in more dissensus oriented behavior (Hettinger, Lindquist, and Martinek 2006). In addition, a recess appointee might not want to alienate a senator by joining a decision to limit state or federal authority.

Based on this we offer the following hypotheses regarding the differences of circuit court recess appointees’ proclivity to vote in a liberal direction pre- and post-confirmation:

Hypothesis 1: A recess appointee will be less likely to cast liberal votes before Senate confirmation.

Hypothesis 2: A recess appointee will be more likely to vote in accordance with his ideology after Senate confirmation.

Hypothesis 3: A recess appointee will be more constrained by the judicial hierarchy after Senate confirmation.

3a: Controlling for the ideology of the judge, a recess appointee will be more likely to cast liberal votes as the relative liberalism of the median of the circuit within which he sits increases after Senate confirmation.

3b: Controlling for the ideology of the judge, a recess appointee will be more likely to cast liberal votes as the relative liberalism of the U.S. Supreme Court increases after Senate confirmation.

Hypothesis 4: A recess appointee will be more likely to depart ideologically from the president after Senate confirmation.

Hypothesis 5: A recess appointee will be more likely to cast liberal votes when the Senate is controlled by the Democrats before Senate confirmation.

Hypothesis 6: A recess appointee will be less likely to cast liberal votes in cases that are highly salient before Senate confirmation.

6a: A recess appointee will be less likely to cast liberal votes in cases that are subsequently petitioned for certiorari before Senate confirmation.

6b: A recess appointee will be less likely to cast liberal votes in cases when the court sits en banc before Senate confirmation.

Hypothesis 7: A recess appointee will be less likely to vote in a liberal direction on a case raising a civil liberties or rights issue before Senate confirmation.

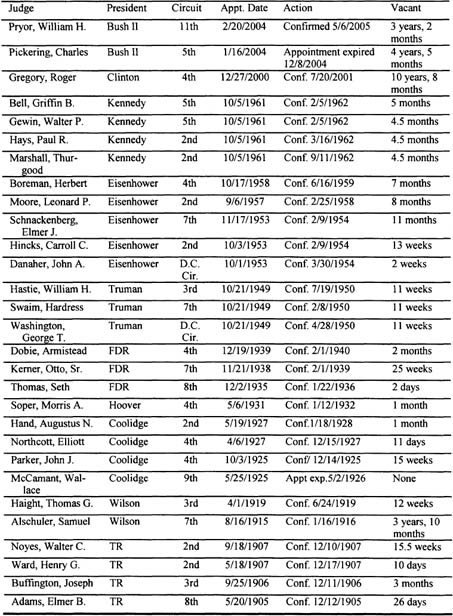

The majority of judicial recess appointments have been to the Federal District courts. Historically this makes sense because the Federal District Court was created by the very first Judiciary Act of 1789 while the current structure of the Courts of Appeals did not come about until a century later. Of course, there are also many more district court seats than positions in the appellate courts, meaning more vacancies to fill. Table 4.1 presents a list of all recess appointed circuit court judges from 1900 through 2007.

One of the most striking details of the table is the length of the vacancies eventually filled by the “contemporary” recess appointments of Gregory, Pickering and Pryor in contrast to earlier instances. While weeks and months were adequate intervals to measure previous vacancies, the standard for these positions is years. The seat eventually filled by Gregory was vacant for over ten years, Pryor’s for over three years and the seat to which Pickering was appointed went unoccupied for almost four and one-half years. Such conspicuous differences are indicative of the changes in tone and practice of judicial nomination and confirmation in the years between these appointments and the most recent previous recess appointment to the circuits in the first year of the Kennedy administration (Binder and Maltzman 2002, Holmes 2007).

Recess appointees to the federal circuit courts could hardly be characterized as marginal, undistinguished or uncontroversial appointments. Several of the judges listed in the table are considered outstanding jurists, with one, Thurgood Marshall, eventually becoming the first African American to serve on the United States Supreme Court. There are several other prominent judges among the recess appointees. David Bazelon, former chief judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, received a recess appointment to his seat by President Harry Truman in 1949. Bazelon was the youngest judge ever appointed to that court and presided for seventeen years over what many consider the nation’s second most influential court (Berger 1993). Bazelon’s decisions significantly expanded the rights of criminal defendants and laid the groundwork for the Supreme Court decision ordering President Richard Nixon to turn over White House tape recordings in the Watergate Scandal (Berger 1993).

Table 4.1: Courts of Appeal Recess Nominees 1900 – 2008

William H. Hastie, a graduate of Amherst College and Harvard Law School, was the first African American to serve as a federal magistrate, the first African American to serve as governor of a federal territory (the Virgin Islands), and became the first African American on the United States Court of Appeals in 1949. The support of African American voters was crucial to President Truman’s surprising 1948 re-election and he was pressured to appoint African Americans to federal judgeships by many supporters, including Mayor William O’Dwyer of New York (Goldman 1997, 99-100). Truman made this key appointment, along with 21 other judicial appointments including the first female district court judge, Burnita Matthews, during the 80th U.S. Senate’s intersession recess. Hastie’s subsequent confirmation met considerable opposition during lengthy, closed-door Judiciary Committee hearings conducted while the judge was hearing cases on the Third Circuit. The committee eventually returned the nomination favorably, although the committee chair did not release the final vote (Goldman 1997, 101).

Griffin Bell, a recess appointee of President John F. Kennedy to the Fifth Circuit, later became attorney general under President Jimmy Carter, was instrumental in vastly increasing the number of women and minorities to serve on the federal bench and in the Justice Department, and led the effort to pass the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act in 1978. Paul Hays, recess appointed to the 2nd Circuit on the same day as Thurgood Marshall, was a distinguished law professor, as was Armistead Dobie, a recess appointee to the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals. Dobie, while serving as dean, is credited with bringing the case study method of instruction to Virginia Law School (4th Circuit History 1998). Others had political careers prior to their appointment. For example, Otto Kerner, Sr. was the Illinois Attorney General and John Danaher was a former United States Senator from Connecticut.

Our first step was to select a collection of votes for valid comparison. We gathered data on each of the judges’ reported decisions from the date they arrived on the bench to the date they were confirmed by the Senate, decisions which could potentially have been affected by the temporary nature of their appointment. We also collected data for a similar number of case-votes from the same judges for the same amount of time following their confirmation. That is, if the judge sat as a recess appointee for one hundred days prior to confirmation, we gathered vote data from the date of the recess appointment to one hundred days following confirmation. Votes were considered “before” or “after” confirmation by comparing the report date of the case with the date of Senate confirmation. Certainly, some votes classified as post-confirmation by this rule were actually cast before the Senate vote, but because the conference dates are not known for these cases and judges are always free to change their votes up until the report date, any earlier demarcation would be arbitrary and possibly wrong. Furthermore, a judge casting a vote shortly before the Senate is scheduled to vote, knowing that the case would not be reported until afterward, could easily be free of whatever pressures he had felt when he knew that his votes could be scrutinized by the president or Senate before receiving a permanent commission.

Just as we did for our Supreme Court voting analyses, we rejected contrasting the justices’ pre-confirmation behavior with the remainder of their careers on the bench. Changes in the institution of the Court, the dynamics of small-group decision-making, the political context, and the legal agenda facing the justices could all change, confounding recess effects. Furthermore, several studies indicate that many justices demonstrate ideological change over time on the bench, which manifests itself in behavioral changes (Epstein et al. 1998; Martin and Quinn 2002). Finally, many court scholars find that certain justices are prone to acclimation effects, changes in their behavior as they adjust to their new role and setting, although such periods of adjustment are thought to take a full term or two before noticeable differences appear (Hagle 1993; Hurwitz and Stefko 2004). This issue in particular cautions against casting too far from the recess period for comparable observations.

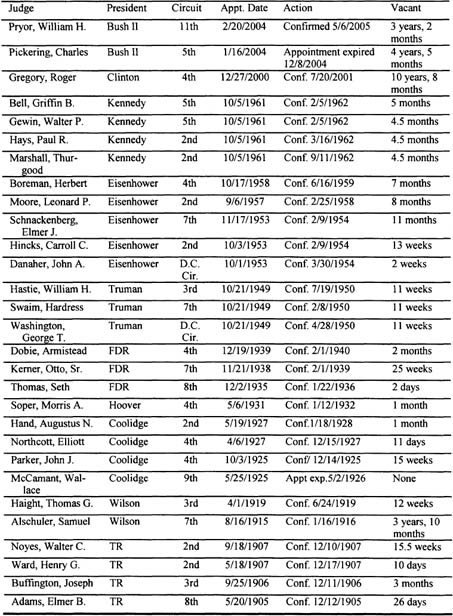

In the post-War era, sixteen judges have received recess appointments to the Appellate courts. For our purposes we modeled the votes of the fourteen appointees for whom we have voting data and ideological measures. They are David Bazelon, H. Nathan Swaim, David Fahy, George T. Washington, William H. Hastie, John A. Danaher, Carroll Hincks, Leonard P. Moore, Griffin Bell, Walter P. Gewin, Paul Hays, Thurgood Marshall, Roger L. Gregory, and William H. Pryor. The ideology metric used for this analysis, the Poole Basic or Common Space (1998), does not provide ideology scores for presidents before Eisenhower, but we extended our analysis back to the late 1940s by using Truman’s Senate score for his ideology as president (Sala and Spriggs 2004). Elmer Schnackenberg and Walter Bastian were excluded because their short recess periods (84 and 73 days, respectively) did not produce any pre-confirmation votes. Charles Pickering, never confirmed by the Senate, could not be analyzed for the opposite reason.

The names, dates of appointment, dates of confirmation, and number of pre- and post-confirmation votes are all listed in Table 4.2. All of the recess appointed judges participated in fewer votes before confirmation than after, probably due to delay between taking the bench and their first reported cases. Having more post-confirmation votes increases the precision of estimates for the post-confirmation parameters and ensures that any votes cast pre-confirmation that are accidentally included among the post-confirm votes, if they are different, are overwhelmed by votes clearly cast after receiving life tenure.

Table 4.2: Court of Appeals Recess Nominees Voting Data

In addition to the pre- and post-confirmation votes of the judges we collected data to test our hypotheses on the nature and direction of the voting. Specifically our dependent variable was the ideological direction of the vote. Following the coding scheme developed by Songer et al. for the United States Court of Appeals Database, we coded a vote as liberal (one) or conservative (zero). Votes which could not be classified as either conservative or liberal under the Songer rules were excluded from the analysis. We collected case-level data for several independent variables. For example whether or not a case was subsequently petitioned for certiorari review (one, zero otherwise), heard en banc (one, zero otherwise), whether the opinion was published (one, zero otherwise) and whether the case was a Civil Liberties/Civil Rights case (one, zero otherwise).

To test our ideological expectations, we collected ideology measures for relevant actors and institutions. The standard contemporary method of identifying political actors in the same ideological space, allowing cardinal distance comparisons, is the Basic or Common Space introduced by Poole (1998), extended to include federal lower court judges by Giles, Hettinger, and Peppers (2002) and to the U.S. Supreme Court by Epstein et al. (2007). We used these scores to place the president, home state senators, judicial circuits, and Supreme Court in comparable ideological space.

Placing the recess-appointed judges in that space proved a more difficult challenge. As noted above, Giles, Hettinger, and Peppers (2001, 2002) introduce a method for measuring the ideology of lower federal court judges that makes use of the norm of senatorial courtesy. Giles et al. (2002) attribute to lower federal court judges the ideology of the political actors involved in the judicial selection process. For judges selected under conditions when senatorial courtesy would apply, when the state in which the judge would sit has one or more senators of the president’s party, they impute the ideology score, or the mean if more than one, of the relevant senator(s). If senatorial courtesy does not apply, the ideology score of the president is given to the judge. Although Giles et al. (2002) confirm the validity and performance of their measure for lower court judges generally, they do not investigate whether the scores are valid for judges selected under a heterodox method such as recess appointment. Are recess appointees selected under the same conditions as those who go through the conventional nomination and confirmation process without taking their seat beforehand?

Fortunately, another method is available to place recess appointees in the Common Space without relying on the selection process. Many scholars have attempted to place actors across institutions in shared ideological space with the use of “bridging observations,” actors serving in both institutions. Poole (1998) for instance, uses instances of members of the House serving in the Senate and presidents serving in the House, Senate or both to create the comparable Common Space measures of members of Congress and presidents. Likewise, Nixon (2004) uses legislators with Common Space scores who served in administrative agencies to place Congress and agency appointees in comparable ideological space. Howard and Nixon (2003) exploit the fact that many members of Congress subsequently became federal court judges (sixty-three judges in all) to estimate a predictive model of first dimension Common Space scores using background characteristics of the judges (see also Howard 2007, 2008). This is the method that we employed to generate ideology scores for the recess-appointed Appeals court judges. The resulting scores correlate with the Judicial Common Space scores (those devised by the Giles et al. method) at 0.84, but several of the scores are considerably different, typically less extreme, than those imputed by the Giles et al. method.

With ideology scores for all relevant actors, we then calculated the ideological difference between each recess appointee and the median of the circuit within which he sat and the contemporaneous president and Supreme Court. The Common Space scores increase in conservatism—movement from negative to positive on the real line indicates increasingly conservative ideology—and the difference scores were calculated by subtracting the circuit, president, or Supreme Court from the appointee’s ideology. Thus, the differences measure how conservative the judge is relative to the actor in question.

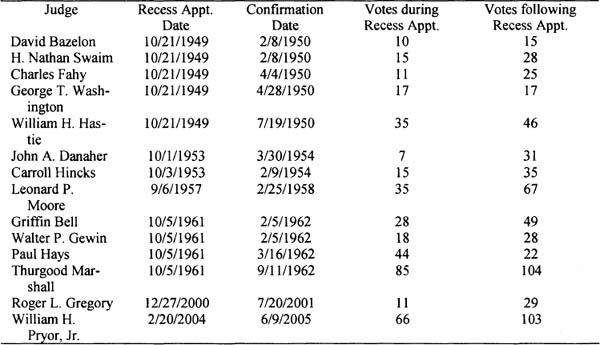

Table 4.3: Descriptive Statistics—Pooled, Before, and After Confirmation

We present descriptive statistics in Table 4.3.

As in the previous table, Table 4.3 splits the data into pre- and post-confirmation samples, but also shows the central tendency and variability for all of the observations combined. The proportion of liberal votes cast by these judges actually decreased slightly among the post-confirmation decisions, but the means and standard deviations of most other variables remained remarkably constant across periods. The only other notable difference was between the proportion of civil liberties and rights cases before and after confirmation.

Model: The outcome we are analyzing, the ideological direction of judges’ votes, is dichotomous, thus we estimate logit models. The dependent variable, whether each recess appointed judge’s vote in each case is liberal (one) or conservative (zero) is specified as a function of independent variables capturing the effect hypothesized above.

The first two variables in the model distinguish the pre-confirmation votes from the post-confirmation votes, the first coded one for cases reported during the judges’ recess periods and zero afterward, the second with the opposite coding. Inclusion of both of these indicators, while suppressing the constant term, allows us to estimate separate intercepts for votes made pre-confirmation and post-confirmation.

Four variables are included making use of the Common Space ideology scores described above. The ideologies of recess appointees, estimated using the Howard and Nixon technique (2003) are entered directly. In addition, we also include ideological differences of the judge’s score from the median of the circuit in which the judge is sitting, the contemporaneous Supreme Court, and the contemporaneous president. We include a variable indicating whether (one) or not (zero) the Democratic Party controlled the Senate at the time of the judge’s vote. The remaining variables are coded based on the cases themselves. In order to capture the salience of certain cases, their likelihood of being consequential enough to draw the attention of the president or Senate, we included indicator variables identifying cases that were petitioned to the Supreme Court after the Court of Appeals’ decision, and whether the judge’s vote was cast in an en banc hearing of a case. Although the certiorari petition follows the judge’s vote, the presence or absence of such a petition is used as an indication of whether the litigants in the case were resourceful and sophisticated enough to pursue further appeals by seeking the attention of the highest court, something a judge might discern while casting the vote. The last variable captures cases that raise civil liberties or rights issues, the kind of cases that are more likely to raise controversies with political actors.

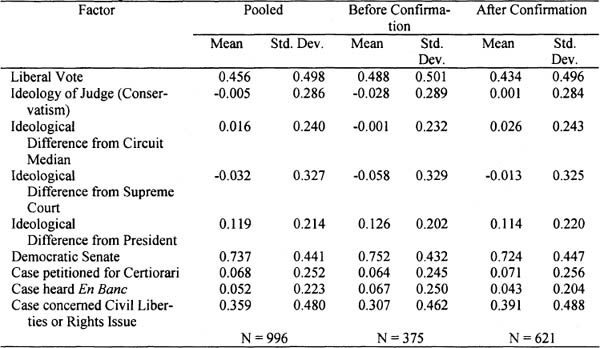

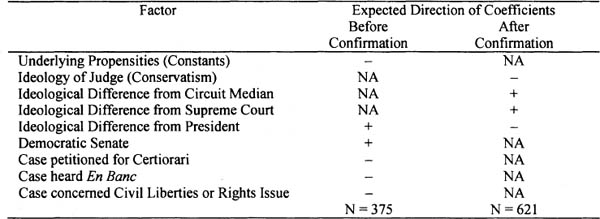

Table 4.4: Hypotheses—Expected Directions of Effects on Voting Liberally

Table 4.4 restates our hypotheses in terms of the expected directions of the variable coefficients. For most variables, we specify directions for either the pre-confirmation period post-confirmation. Conditions for which we expect no effect are indicated with NA.

Our hypotheses propose that the effects of these factors will differ depending on whether or not the recess-appointed judge has been confirmed. Pre-confirmation, we anticipate that recess-appointed judges will be less likely in general to vote liberally and even more so in cases subsequently appealed to the Supreme Court, heard en banc, or involving civil liberties or civil rights issues out of concern for stirring controversy about their impending nomination. We also expect that these judges will be conform to the preferences of those who must act on that nomination, being more likely to vote liberally when the Senate is controlled by Democrats and when the sitting president is more liberal than the judge. Following Senate confirmation, we hypothesize that more conservative judges will be less likely to vote liberally and that judges will be free of the constraint to conform to the ideology of the president. We expect that these judges will be constrained, however, by the preferences of their circuit and the U.S. Supreme Court, moderating their ideological predisposition in the direction of these hierarchical superiors.

In order to capture the conditional effects of these variables, we specify conditional models, estimating separate coefficients of the variables’ effects before and after a judge is confirmed. We employ two strategies, a “multiplicative interaction” model, and a “regime” model. The former is the traditional “interactive” model widely used in social sciences in which variables whose effects on the outcome are thought to depend on the value of another variable are multiplied by that variable and the resulting term added to the specification. The un-multiplied terms are referred to as the “constituent” terms while the new terms are the “interactions.” The second approach is useful when the condition upon which other effects are thought to depend is discrete, as it is here. We produce the “regime” model by multiplying the constituent terms by both variables indicating whether a vote was made before or after confirmation and enter those two sets of covariates into the model in place of the constituent terms. Thus, in the regime model, one set of covariates take their observed values for the before confirmation votes and are zero otherwise, while the other set take their observed values only after confirmation. The regime model allows us to estimate separate marginal effects on the outcome for the covariates across conditions (before and after confirmation) without the complications of the traditional interaction model (Brambor, Clark, and Golder 2006, 69).

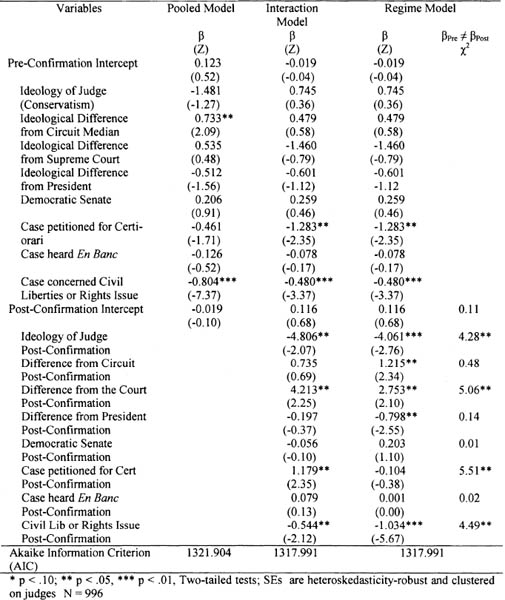

As a basis for comparison, we estimated a logit model pooling the pre- and post-confirmation votes, allowing only the constant to vary across these conditions. The standard errors for this and the two subsequent models are heteroskedasticity-robust, clustered on the individual justices. The results appear in Table 4.5.

Coefficients and test statistics for the pooled model, combining votes cast before and after confirmation, appear in the first column. This model produces two statistically significant coefficients. Ideological difference from the circuit median has a positive effect and the presence of a civil liberties or civil rights issue has a negative impact on the likelihood of voting liberally. The ideology of the judge is controlled for separately, meaning that with ideology constant, the judges were more likely to cast a liberal vote when their circuit was more liberal than themselves (and less likely when the circuit was more conservative). This is consistent with the hypothesized effect for post-confirmation votes, which were by far the more numerous observations in the pooled data. The negative coefficient for civil liberties issues is consistent with the pre-confirmation hypothesis. The remaining coefficients are not statistically significant, but the pattern of their signs splits between the two sets of hypotheses. Of the four directional hypotheses specified for post-confirmation votes, all are in the expected direction, while four of the six directional hypotheses for pre-confirm votes are consistent with the results. The only coefficient with opposite expectations across regimes, ideological difference from the president, is consistent with the post-confirmation hypothesis.

Table 4.5: Logit Models of Liberal Vote

The second column reports the results of the multiplicative interactive model. Looking first at the constituent terms, which can be interpreted as the marginal effects of these variables on vote choice for pre-confirmation votes, we find that two coefficients are statistically significant. Certiorari petition and civil liberties issues are significant and negative, consistent with the hypotheses for these variables. Of the remaining four directional hypotheses, three estimated effects are in the expected direction, all save ideological difference from the president, although none are statistically distinguishable from zero.

In this model, the interactive terms represent the departures from the estimated constituent effects for votes cast after confirmation, rather than marginal effects. Interpreting the estimated effects of changes in the variables on liberal voting requires taking account of both estimated effects, and assessment of whether those effects are statistically significant requires calculation of compound standard errors taking account of the covariance of the estimated effects. If anything, the coefficients and test statistics of interaction terms might reveal whether the marginal effects of the constituent terms are significantly conditional on each other, although perhaps not even that (Brambor et al. 2006, 74).

Comparing the interaction model to the pooled model, we find that for the estimated marginal effects of pre-confirmation votes, the significance of circuit difference disappears, the magnitude of its coefficient shrinking. Civil liberties issues remain statistically significant and negative, as expected. The coefficient for cases petitioned to the Supreme Court after review by the appeals judges, however, is now significant and negative, the coefficient substantially larger than in the pooled model. We hypothesized just such an effect.

The coefficients on those terms indicate the direction of the conditional effects on the constituent terms. Thus, we know that the effect of judges’ ideologies on the likelihood of voting liberally departs changes after confirmation. This confirms our hypothesis for relationship was just as we expected—more conservative judges are less likely to cast liberal votes after confirmation, but not before. Ideological difference from the Supreme Court also changes, but in this case positively, suggesting that after confirmation judges are more likely to vote liberally as the Supreme Court’s relative liberalism increases, holding the ideology of the judge and other conditions, constant.

Perhaps the most interesting of the interactive effects is the coefficient for cases petitioned for certiorari. The interactive term is positive, significant, and very similar in magnitude to the significant negative constituent term coefficient. This suggests that the impact of subsequent appeal to the Supreme Court mostly vanishes in the post-confirmation regime. Post-confirmation, a federal appeals judge is secure in their voting. The statistical significance of the overall effect is unknown, but since our expectation was that the certiorari effect would disappear after confirmation, learning that the resulting effect was not distinguishable from zero, which seems likely, would be consistent with our hypothesis.

The last remaining significant interaction is for the effect of civil liberties and rights issues after confirmation. The coefficient is in the same direction as the constituent term, suggesting that the impact of such issues makes liberal votes even less likely after the judges were confirmed. This is contrary to our hypothesis, which expected no effect after confirmation. The remaining coefficients are not significant, although the estimated effects are in expected directions. It remains to be seen whether the conditional marginal effects after confirmation are statistically significant.

Another issue with interactions, specific to nonlinear models such as logit, is that test statistics for the interactive terms in such models depend on the assumption that the residual variation in the dependent variable is equal across populations (Allison 1999). In other words, if the scale of the underlying propensities toward the outcome is different among pre-confirmation votes than among post-confirmation votes, that unequal residual variation could result in misleading hypothesis tests for interactive effects (Hoetker 2007). Fortunately, a class of models known as heterogeneous choice or location-scale models allows researchers to estimate valid test statistics even if residual variance differs across the populations defined by the interacting variable. We re-estimated the interactive and regime models using a heteroskedastic logit model, allowing the residual variance to change with the post-confirmation indicator, and confirmed that our results were robust to this assumption.

To untangle the marginal effects of the variables after confirmation, the regimes model results are reported in the third column of Table 4.5. Unlike the interaction model, in the regimes model effects estimated for the pre-confirmation votes are absent for the post-confirmation votes. Thus, the coefficients below the post-confirm intercept in column 3 are equivalent to the results of a logit model using only the post-confirmation votes. In fact, the results of the regimes model are equivalent to estimating two parallel logit models on the pre- and post-confirm votes separately. A virtue of estimating them together, however, is that we can easily test whether the pre-confirmation and post-confirmation coefficients are equal to each other. A series of chi-square tests are reported in the final column. Significant results indicate that we can reject the null that the two coefficients are equal.

The results for the pre-confirm votes are, as they should be, exactly the same as the constituent effects for the interaction model. The coefficients of the regime model for the post-confirm votes, however, are estimated effects of changes in these variables on liberal voting, rather than departures from the constituent effects. Interpreting these, we observe that the impact of judicial ideology on vote choice is negative after confirmation. The more conservative the judge, the less likely he is to cast a liberal vote, but only after Senate confirmation. These results are consistent with Hypothesis 2, and the chi-square test confirms that the coefficients are distinguishable from each other.

We find strong support for Hypothesis 3 which was that judges would be constrained by the judicial hierarchy after confirmation but not before, when their concerns were focused more on the political actors controlling their permanent appointment. This hypothesis has two parts: that liberal voting would be responsive to the Supreme Court and to the Court of Appeals circuit median only after the judge was confirmed. The coefficients for ideological difference from the high court and the circuit are not statistically distinct from zero for pre-confirmation votes, but significant and positive after confirmation, indicating that judges were more likely to vote liberally when the court within which they sit or the hierarchically superior court was more liberal, and less likely to cast liberal votes when they were more conservative. The Supreme Court coefficients are statistically distinct from each other as well, according to the chi-square test. The test for the circuit court effects does not confirm that the coefficients are different, but the fact that difference from the circuit was positive and significant in the pooled model, combined with the pattern for the pre- and post-confirm votes suggests that at the very least, the effect of circuit ideology is much more pronounced after permanent appointment.

The results for the ideology of the president are similar to those for the circuit courts. We estimate a statistically significant departure from the president’s ideology only after confirmation. In that regime, the conservatism of the judge relative to the president makes liberal votes less likely, while the null cannot be rejected for votes before confirmation. Again, the chi-square test also fails to reject the null that the coefficients are similar, but ideological departure from the president appears to be much more muted before the judge is confirmed. We find no evidence that Democratic control of the Senate had any effect on liberal voting by recess appointees before or after confirmation. Thus, Hypothesis 5 receives no formal support from the results.

We do find support, however, for Hypothesis 6, which contended that judges would be reluctant to cast liberal votes on salient cases before they were confirmed. One of our indicators of case salience, the subsequent petition of a decision for review by the Supreme Court, has a significant and negative impact before confirmation on liberal voting, but a null finding afterward. The chi-square test confirms that these coefficients, both negative, are distinct, meaning that even if there is some negative effect of cert-petitioned cases after confirmation, it is considerably smaller than the effect before confirmation. We discover no effects of en banc cases on the incidence of liberal voting, either before or after confirmation, although the estimates have opposite signs and the pre-confirmation value is in the hypothesized direction, while the post-confirmation coefficient is essentially zero.

The results for our test of Hypothesis 7 are mixed. We expected that cases raising civil liberties and rights issues would be less likely to elicit liberal votes before confirmation but not afterward, but we found that civil liberties cases were less likely to receive liberal votes before and after confirmation. In fact, liberal votes were less likely in such cases after confirmation than before, as indicated by the relative sizes of the coefficients and the significant chi-square leads us to reject the null that these coefficients are equal.

We devised seven hypotheses about the differences in the effects of various ideological, political, and contextual effects on the propensity of recess-appointed judges to vote liberally before and after they received Senate confirmation. Many of those hypotheses were confirmed, some powerfully so. The most pronounced effect was the dramatic change in the relationship between ideology and vote choice before and after a judge is confirmed to a permanent judicial seat. Before confirmation, ideology has no discernable impact on votes and the coefficient estimate is contrary to its expected direction. After confirmation, however, the effect of ideology is substantially large, statistically significant, and in the direction predicted by decades of judicial politics scholarship. In short, judges’ votes exhibit much more independence after confirmation than before.

Also consistent with our expectations, the judicial hierarchy does not have any statistically significant effect on the votes of judges sitting via recess appointment, but appears to constrain judges’ vote choices after they are confirmed by the Senate. These results can be interpreted as the influences of the principle-agency relationships between appeals court judges, the circuits within which they sit, and the Supreme Court above them. Those influences are less pressing on the judges when the fate of their appointment is still in the hands of the president and Senate, but relevant after they gain the protections of Article III. Another even more troubling interpretation is that the “ideology” of the circuit and Supreme Court medians indicate the state of the law that the judges are bound to apply. These judges seem unaffected by such influences until they receive Senate confirmation. Recess appointees appear more inclined to follow their own legal lights, measured by their ideology, as well as to exhibit the influence of the legal system once they become permanent members of the judiciary.

We can learn more about the results graphically than through coefficients and test statistics. In Figure 4.1, we present predicted probabilities of the likelihood of voting liberally for pre- and post-confirmation recess appointees. In addition to confirmation, we also vary the salience factor, subsequent petition for certiorari. All other variables are set at central values, means for continuous variables and modes for dichotomous variables. The impact of case salience is quite clear. Typical cases that are not subsequently appealed to the Supreme Court are nearly 60 percent likely to receive liberal votes from our judges before confirmation, but varying only the certiorari variable reduces the predicted probability to below 30 percent. We observe that the statistically average case after confirmation has nearly the same likelihood of receiving a liberal vote as before, but varying the certiorari indicator has almost no effect on the likelihood of voting liberally. The impact of salience on vote choice before the Senate has confirmed the judge vanishes afterward.

In Figure 4.2, we graph changes in the predicted probabilities of a liberal vote across the range of judicial ideologies observed in our sample for judges pre-confirmation and post-confirmation. The X-axis indicates the conservatism of the judge, from left to right. All of the remaining variables are fixed at their central values, means for continuous variables and modes for binary variables.

For votes cast before confirmation, ideology has a mild but counterintuitive effect of increasing the likelihood of casting a vote. Following confirmation, however, the effect of ideology is pronounced and as expected. These appeals court judges are much more likely to cast liberal votes when they themselves are liberal after receiving Senate consent, and that probability falls sharply and consistently to the conservative extreme, ranging from about 90 percent for the most liberal judge to just above 10 percent for the most conservative.

Figure 4.3 presents a similar graph of the change in predicted probability of a liberal vote across the range of ideological difference between the judge and the median of his circuit. The measure is a difference, subtracting the median ideology from that of the judge, so positive numbers reflect how much more conservative the judge is than the circuit, while negative numbers indicate how much more conservative the circuit is than the judge. Our hypothesis for this variable was one of institutional constraint. We anticipated that after confirmation, judges would be more likely to cast liberal votes when the circuit was substantially more liberal than the judge, since the impact of the judge’s ideology is accounted for separately. Alternatively, we expected that ideological difference from the circuit would have no effect before the judge becomes a permanent member of the judicial branch.

The predicted probabilities bear out these expectations. The effect of ideological difference from the circuit is nearly flat for pre-confirmation votes, but changes from below 40 percent to nearly 70 percent as the relative liberalism of the circuit grows. The effect of ideological difference after confirmation is about three times the effect before confirmation over the same range.

The evidence indicates that judicial recess appointments do threaten judicial independence. Our results demonstrate that these judges did alter their voting pre-confirmation, based on their observed behavior afterward. Judges sitting by temporary recess appointment do not vote according to their ideological predispositions and do not appear to be responsive to the direction of their circuit or the Supreme Court. Rather, we contend, these judges are concerned with the impression that their actions on the bench make on the president who must renominate and support them and the Senate that must vote to confirm them. These judges also avoided liberal votes in cases subsequently appealed to the Supreme Court by the unsuccessful party and in cases raising civil liberties and civil rights issues during their recess appointment period.

In contrast, we found that these same judges’ voting behavior was very consistent with their ideology, measured independently of their own voting records, after they were confirmed. Although many scholars might not see the virtue of judges voting consistently with their ideological predisposition, we see ideological voting at the appellate level as the exercise of individual discretion in cases based on sincerely held beliefs about the state of the law. Judges chosen by political actors to apply their understanding of the law to cases necessarily bring with them distinctions that are manifest in the exercise of judicial discretion. This exercise is entirely consistent with “good faith judging” in a way that voting in order to please actors outside of the judiciary is not (Gillman 2001).

We also find that the recess-appointed judges were much more responsive in their voting behavior to the ideological direction of the circuit in which they sat and the U.S. Supreme Court following their permanent appointment than they were beforehand. In a sense, judges sitting temporarily, awaiting the approval of the political branches to keep their jobs, are not full members of the judicial branch during that time, but visiting jurists on a “look-see” extended interview, as Herz (2005) characterizes the situation. The important distinction, however, between these situations is that their colleagues have no role at all in deciding whether the visiting judge will receive an offer of permanent employment.

Because recess appointees must still be confirmed by the Senate, they lack the independence accorded by the tenure and pay protections of Article III of the United States Constitution. Their exercise of judicial power, therefore, should be considered at least as suspect as the circumstance found unconstitutional in Northern Pipeline Co. (1982). Certainly the evidence presented herein demonstrates that judges sitting via recess appointment are not voting their sincere preferences. Judicial independence, along with judicial review, allows judges to fulfill their prescribed role of protecting minority rights when they are under attack, but a recess appointee must be mindful of the president and the Senate, strategically choosing to avoid controversial rulings and behavior that would lead to unwanted attention. Rather than acting as a member of an independent third branch with the protection of lifetime tenure, the recess appointee must keep “one eye over his shoulder on Congress.”

Under a separated powers system, each branch has overlapping responsibilities and power subject to control and review by the other branches of government. However, once confirmed by the Senate, Article III judges are guaranteed lifetime tenure and protection from decreases in their salary. Although Congress does have some limited checks on the judiciary post-confirmation, and there is evidence that threat of congressional retaliation against the judiciary can constrain the choices of a judge, the evidence presented here shows that a recess appointee sits in a more precarious position, and, consequently, the independence provided by the Constitution is diminished.

Judges sitting via recess appointment are in a different position than confirmed justices. Our results raise serious concerns about the validity of permitting recess-appointed judges to exercise judicial power, but they also echo the concerns of scholars who question the presumption of judicial independence. We assume that life-tenured justices are more insulated from external influences, but even the protections of Article III cannot ensure that sitting judges are entirely immune to being influenced by external pressures.