The Creative Word of the Universe

‘O Man, speak, and the source and life of the universe shall be revealed through you.’ Rudolf Steiner

In the course of our considerations we have been led onwards through the abundance of natural phenomena to recognize that there is something spiritual expressed in them. With the use of many examples we have attempted to show how forms arise out of the gaseous or liquid elements, but above all how it is to movement that we must ascribe these forms. They are the movements of a spiritually living being descending from the world of cosmic laws to take on bodily shape through the circulations of air and water. At all stages of this descent, movement as such has constantly shown itself to be the tool used by a world of being working in upon the elements.

If we observe how in embryonic development an organism is gradually created out of the liquid, our attention is drawn to movements that play their part in fashioning it according to invisible plans, though they are themselves not all visible in the finished shape. They are like the hands of the potter in their abundance of possibilities, moulding a vessel from without and within and then withdrawing again into the invisible world. They are movements which originate in the will and spirit of a living being. As movements they are actually the creative and formative forces through which the idea underlying the forms can be impressed on the elements. Once this has been accomplished, the creative movement releases the form and appears in it as a function, of which the embodied being may now make use.

The human larynx is one of the most beautiful examples of this. All the moving forms we have seen in the course of these considerations may be found again in the possibilities of movement of the human larynx. This means that all the movements that nature uses in the creation of its creatures and also all those movements which, once created, the creatures may use, may be found in the human larynx— as though in a great gathering of creative beings. The larynx has infinite possibilities of movement, and with every one of them it can delicately influence the stream of breath and impress moving forms upon the flow of air, which then become audible for us as sounds, notes, speech.

Examine the structure of the larynx and its adjacent organs. It is obvious that in its differentiated forms it is not so much the resting form which is significant as the moving form with its immense possibilities of variation. This is expressed in the way the numerous joints and groups of muscles are co-ordinated in a great variety of ways. The significance of all these joint and muscle actions can be understood if we realize that in their interplay these movements serve to mould the stream of air and form it into the stream of speech. For the stream of air is obstructed by a great variety of forms: narrowing slits, elastic membranes, pouches, spiralling curves— obstacles of the most varied form, elasticity and plasticity (vocal cords, epiglottis, soft palate, uvula, tongue, teeth, lips and so on). Each of these moulds the stream of air and forms it in a particular way; all together they can impress upon it an endless variety of shapes and forms.

We have met with the sensitive stream of air that arises when air emerges through a narrow slit. A corresponding phenomenon may be found in the larynx, where the stream of air issuing from the lungs has to pass through the slit between the vocal cords. The stream causes these to vibrate and the vibrations immediately work back on it, dividing it up rhythmically and becoming the source of the audible sound. Through the further moulding of the stream of air, in the interplay of the adjacent organs, further formation of the sound takes place. According to the varying shapes made by the cavities of the mouth and throat, so the sound is altered and becomes the many different modulations of the voice. Some of these are magnified into fundamental sounds, others are suppressed, whereby the most varied timbres arise. We experienced these differentiated sounds as the characteristic vowels: their origin is where the stream of air is restricted and has to pass the vocal cords. Furthermore, with palate, tongue, teeth and lips the human being can mould the stream of air in such a way as to produce the consonants.

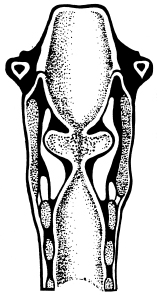

Diagram of the human larynx

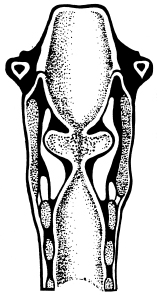

Human larynx, posterior view

It is at the vocal cords that the whole soul life of a human being flows into the formation of the stream of speech, the soul’s means of expression. The as yet unformed stream of air issues forth from the region of the will; at the vocal cords it receives the impulses that come from the conscious soul life of the human being, striving to communicate with the outer world (articulation). As yet unformed, the air coming from the lung enters the larynx. It emerges from the organs of speech structured in finest detail—in waves, vibrations and vortices; definite, though ever-changing formations. Their richly varied interplay builds complicated forms out of the fundamental, archetypal movements of the streaming air.1

The delicate vibrations that mould the sensitive flame through the elasticity of the air have their counterpart in the larynx in the delicate vibrations of soul life. The soul uses the elasticity of the vocal cords like an instrument on which to play. Here, the instrument which influences the sensitive flame from a distance has entered directly into the walls of the slit. The soul of the human being allows its inner abundance of tension and relaxation, sympathy and antipathy to play on the elastic vocal cords, stretching or relaxing, lengthening or shortening them, narrowing or widening the slit. Accordingly they vibrate in fast or slow rhythms. In the same way it is the soul of the human being that activates the interplay of the adjacent organs.

We have already pointed out how the air can be the bearer of soul forces and how it is particularly its elasticity which, like a tool, can be used by the soul as it expands and contracts in sympathy and antipathy. In the larynx we see a wonderful co-operation in this triad of air, soul and elasticity. The delicate interplay of the elasticity of the air is solidified to a visible form in the elasticity of the vocal cords and the groups of muscles in the larynx. The rich inner life of a human being becomes almost physically graspable; airy forms are constantly being born in the larynx.

It is possible to observe these forms of air if single phases of this constantly changing play of movement in the larynx are made visible in a suitable experimental arrangement, outside the human larynx. Since air and water have certain features in common, the quick movements of the air may be transposed into the slower movements of water, as long as certain rules are observed.

If water or air is allowed to issue from a slit, vortex trains arise, with which we are familiar (Plate 24). Similar trains of vortices may be created by drawing a small rod through water or air. A single such vortex train will of course correspond in the larynx only to the most simple form of sound, caused by one particular position of the organs of speech (Plate 29). But even the same sound uttered several times will change the form of the air; the same impulse is again and again inserted into the formation of air that has already been created (Plate 31). If impulses of different kinds and strengths (corresponding to the vowels and consonants of a word) follow on one another at short intervals, more complicated forms will arise accordingly (Plate 32).

We may recall that the interplay of the most varied streams and moulding movements is necessary in order to create the shape of even a simple organ. This will help us to understand that in the organ of speech, with its constant variations of movement, a great variety of organ-like forms are created out of the air. We can actually see the way in which forms issue forth from the word. Plate 32 shows how many small forms, all in a flowing relationship with one another, are incorporated like organs in a great, rhythmically arranged form. It is like a picture of the invisible streaming forces which weave an organism and its separate organs into a whole. Even though these formations are at a very simple stage, they show something of the rich variety of possibilities inherent in movements working together. (See also Plates 29–32.)

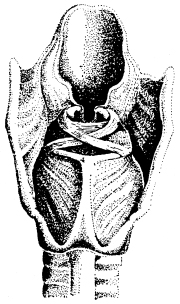

Human larynx, anterior view

The variety of formations which nature and the human larynx allow to stream forth must be infinitely great! Uniting all nature’s formative possibilities in the human form, man is able to bring forth from the larynx not only all the single organic forms of nature but also a union of them all. This means that the human being unites in the organs of speech all the formative movements by which he has been created. And so within man another being, a moving human being, is at work.

Sagittal section through the speech organs of the human being (after Corning)

It is the wonder of the biblical story of the Creation that Adam is able to utter the names of all creatures and things and also his own name—the mystery of the human being. He can do so because the Godhead first inspired him with living forming forces—the breath of life—creating him in accordance with them. The creative word of the universe itself, original movement of spirit, formed him and his larynx; now it again sounds forth from him in creative forms. No wonder that these laws are to be found in the larynx!

In the arrangement of the organs of human speech, as they are drawn in the accompanying sketch, is revealed once more the archetypal gesture of all living, streaming movement; it is pictured here in solid organic form. ‘Every time we speak we produce out of ourselves something of that creative element which existed in the ancient days of creation, when the human being was moulded out of cosmic depths, out of ethereal realms, into an airy form, before acquiring a fluid form and, later still, a solid earthly body. Every time we speak, we transport ourselves back into the evolution of the universe and man as it was in primeval ages ...’ (See Steiner Eurythmy as Visible Speech).

The stream of speech, like a flaming sword, pours forth from human beings; announcing the inner secret of their creation. It is the ‘sensitive flame’, issuing from the region of the will, on which they can impress their moods—the ‘meteorology’ of their soul. But they also communicate this to those around them, who take it in through the activity of listening; it is recreated in the receptive processes of the organ of hearing. The sensitive flame is the underlying concept both of the larynx and of the organ of hearing. In both it is the creative principle—an ‘organ’ not as yet brought to the resting state of form, but retaining its functional quality as pure movement. It functions in the intermediate region where forms are for ever being created; with its delicate sensitive boundary surface, it is a portal through which all the imponderable forces may enter into the world of earthly substance.

We have come to know the sensitive boundary surfaces on a large scale in the weather fronts with their accompanying heat processes. They are the organs of hearing that listen to what comes from the cosmic universe; at the same time they are the organs of speech through which the starry universe expresses itself, in a manner that is coloured by the moody nature of the earthly sphere. As on a small scale in the larynx, so also in these gigantic speech organs, forms are created, which, on a grand scale, contain all the possibilities of creation. In man these creative possibilities are united in a streaming together of the creative word of the universe. ‘All things were made by the Word, and without the Word was not any thing made that was made.’

We have as yet only spoken in general about many possibilities of movement, but we will now call them by their true names. In the abundance of possible movements in the organ of speech, certain ever-repeated characteristic archetypal movements, which we know as the vowels and consonants, can be singled out. As characteristic elements of movement they remain unaltered throughout the languages of all time. Indeed, it is out of these fundamental gestures or sound-movements, which have a spiritual origin, that the manifold movements of the larynx arise in the first place, and it is these archetypal movements of the vowels and consonants that give birth to all manner of forms. The true name of a thing is pronounced when the form-creating, archetypal gestures of the consonants really do create the thing as a moving form.

There is nothing in nature that cannot be created and named by speech, for in naming a thing, the human being, through speech, creates it anew as a form in the space of air, in so far as the words still partake of the living origin of language. Everything surrounding us in nature has a part in the original gestures, but only a part. The human being, uniting all nature, has at his disposal the whole—a whole alphabet. In olden times the archetypal gestures were experienced each in its own one-sided aspect; the gestures of certain cosmic forces were seen in images of animal forms. The world of consonants was arranged as a zodiac; the vowels represented the moving world of the planets. The spoken word is more than the intellectual naming of a thing, more than a ‘nomen’; it is form-creating, spiritual reality.

If the larynx holds within it all the archetypal gestures of the world of the stars that lead to the human form, if, in other words, it contains over again a whole human being as a moving form, then only a small step further is needed to the thought that the archetypal gestures may not only be made audible, through the larynx, but also visible, through the whole moving human form. This would lead to an art of movement that uses the moving human being as a means of expression according to the laws of the universal alphabet through which he was born out of the cosmos. This new art, the art of eurythmy, together with a revival of the art of speech based on the same cosmic background, has been created by Rudolf Steiner. In eurythmy the manifold movements of the ethereal archetypal gestures are made visible through the whole human form; they are the basic gestures of the physical larynx which mould the stream of air.

As well as speech, human beings also bear within them the world of music. This, too, they can make visible according to its laws through the movement of the human form. Speech and eurythmy are in the end the same experience, one auditory, the other visual. Man and the world have been created by speech—the eurythmy of spiritually creative beings. Speech and eurythmy are given to human beings because they themselves are to become creative in spirit.

‘The human being as he stands before us is a completed form. But this form has been created out of movement. It has arisen from archetypal forms which were continually taking shape and passing away again. Movement does not proceed from quiescence; on the contrary, that which is in a state of rest originates in movement. In eurythmy we are reaching back to primordial movement.

‘What is it that my Creator, working out of original, cosmic being, does in me as a human being?

‘To answer this question you must make movements of eurythmy. God makes eurythmy movements, and as the result of His eurythmy there arises the form of man ...’ (See Steiner Eurythmy as Visible Speech.)

Whether we speak of streaming water or moving air, of the formation of organs or the movements of the human form, of speech, of eurythmy or of the regulating movements of the stars, it is all one: the archetypal gesture of the cosmic alphabet, the word of the universe, which uses movement in order to bring forth nature and man.

1 All these descriptions refer to the formation of the speech sounds and not to the content of what is spoken.