In the middle of January, Colpix put out another single from the July 1959 sessions, “The Other Woman” backed with “It Might as Well Be Spring,” a sign the label intended to make Nina one of its stars. The record was a teaser for the anticipated release of two full-scale albums, The Amazing Nina Simone, made up of a dozen tracks from those sessions, including the songs on the single, and the Town Hall concert, marketed simply as Nina Simone at Town Hall. But before Colpix could get the LPs in circulation, Syd Nathan issued another album called Nina Simone and Her Friends, even though only four tracks were from Nina and only two of those, “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” and “For All We Know,” had not been previously released. Songs by Carmen McRae and Chris Connor made up the rest of the album.

Nina was livid. “I had no idea that Bethlehem had any intention to do such a thing until I saw it on display in a record store window in Greenwich Village,” she fumed. In one way, though, Nathan’s move brought Nina extra exposure. As Cash Box noted, she was given featured billing over Connor and McRae, who seemed like afterthoughts. Nina also received the headliner slot on a three-act jazz show in Chicago February 12.

So much had happened since Nina last played the Queen Mary Room at the Rittenhouse Hotel that she might have forgotten her free performance at a 1957 benefit for disabled children. But the officers at the Mildred Malschick Fuhrman Charities hadn’t. They were sponsoring the first annual jazz festival at Philadelphia’s Academy of Music March 13, and they wanted Nina. This time she would be paid $2,000 for two performances as the headliner, even though the Dizzy Gillespie quintet, the Four Freshmen, and Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers were also on the bill. A few days before the event, Nina sat down with Frank Brookhouser of the Bulletin, who was still writing his “Man About Town” column, and together they traced her trajectory from child star in the church to acclaimed jazz singer. “I formed a group called the Waymon Sisters with two of my sisters,” she told Brookhouser, a description of its origins that would have bemused Lucille and Dorothy. Even while she was playing church music, Nina went on, “I found it hard to resist sneaking in an extra beat in the arrangements now and then, although mother didn’t approve.” In her more recent creations, she said, “I wanted to get into my music more of the feeling I had once put into those spirituals.”

If she hadn’t completely given up her dream of a classical music career, Nina was now rewriting her narrative as though this state of affairs had been in the cards all along, improvising with words the same way she wove Bach into her blues.

NINA SPENT THE REST of March in New York at the Village Vanguard, this time with her own trio. The otherwise routine engagement was broken up by two events that reflected Nina’s growing profile. On March 24 she made her first national television appearance on the NBC Today show. She played it safe with two mainstream selections, each coincidentally cowritten by Jule Styne, “Just in Time” and “Time after Time.” Two days later she headlined another jazz event at Town Hall on a bill that included drummer Max Roach, saxophonist Sonny Stitt, and pianist Thelonious Monk’s quartet. But for all its potential, this night would have none of the charm of the previous September evening. A faulty microphone prevented host Mort Fega, a jazz disc jockey, from being heard when he introduced the acts, and a glitch in the lineup delayed Nina’s appearance. When she finally came on, she told the audience that some of the music was “created right here on the stage.” The Times’s Wilson, who was intrigued enough to see Nina again, found her anything but creative. He said her set was based “on the valid theory that if one note is repeated often enough, a jazz audience will eventually applaud.”

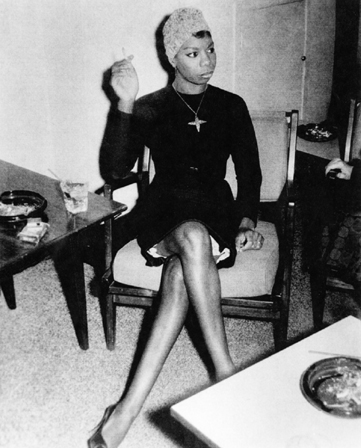

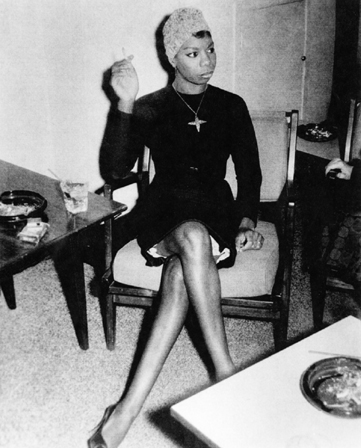

Nina Simone, c. 1959-60

(Author’s photo)

BEN RILEY AND AL played regularly now with Nina, but the bass chair remained unsettled. Ben’s friend Ron Carter, who would go on to a distinguished career with Miles Davis and countless other musicians, filled in when Nina spent a week at Storyville, the Boston jazz club opened by impresario George Wein. But although the fit was good, Carter wanted to work with an instrumental group and chose not to stay on for Nina’s upcoming dates. Riley scouted around for another bass player who could meet the group in Milwaukee April 22 for a week at Henri’s Show Lounge, one of the better-known downtown clubs. He settled on Chris White, a young bassist from Brooklyn who had studied at the Manhattan School of Music. Ben had seen Chris at some of the regular jam sessions at small clubs around 125th Street and thought he could do the job—exactly why Chris had joined as many of those jams as he could.

The timing couldn’t have been better. Ben called just as Chris was prepared to give up on music and take a job at the post office. So instead of donning a uniform and sorting mail, he received a plane ticket to Milwaukee and instructions to meet Nina at 730 North Fifth Street, where Henri’s was located. The music would be waiting for him.

This was Nina’s first time at Henri’s, and the minute she walked in, she sought out the manager. “Could you please wipe down the piano?” she asked in a tone that suggested only one right answer. “I’m not going to touch that instrument.” The moment told Chris everything he needed to know about this new job: Nina had standards, and he had to toe the line, musically and otherwise.

Before more out-of-town dates in Atlanta, Miami, and Detroit, Nina called a rehearsal at the apartment on Central Park West. When Chris got off the elevator and entered the foyer of 15D, he noticed a big umbrella on the floor bent at an unusual angle just as a white man walked out, head down, a bloody gash visible on his forehead. The white man, he came to realize, was Nina’s husband Don, and he surmised that the two had had a fight. Nina said nothing about it, and they went right into rehearsal. “It was sort of awkward at the beginning,” Chris admitted.

Faye Anderson had made the Milwaukee trip to help with suitcases, scheduling, and the like, but Don had not. It was symptomatic of their marital troubles, which now provided fodder for gossip columns. Dorothy Kilgallen led her April 4 installment with the news that Nina and Don “have separated for the fifth time they say.” Eight days later The Philadelphia Tribune reported that Nina’s “friends and relatives are working ‘overtime’ in efforts to patch up her differences with her white husband. But other talk is that Nina and Don have already agreed to disagree in Reno fashion.”

“I had originally married Don so I’d never be alone,” Nina wrote in her memoir. But more often than not, she would return from a job “hoping he wouldn’t be there. Some stupid arrangement,” she conceded. She had mused that they reconciled those four other times because “we can’t keep away from each other.” But now the separation was for good.

The rupture in Nina’s personal life coincided with another change in her musical life. Ben told her he was leaving in the middle of June to take the drum chair with the Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis-Johnny Griffin quintet. “It was me playing with the hard core and how I wanted to play,” he said. “Nina was more of a quiet accompaniment. She was a tremendous musician. She had a good feel—that’s what made me stay as long as I did.”

Chris White recommended Bobby Hamilton, whom he’d known since they played together as teenagers in the “Stablemate Quintet,” their high school band in Brooklyn. Bobby studied at the Hartnett School of Music and had also taken lessons with one of the percussionists from the Boston Symphony. Nina told Chris to have Bobby make the next rehearsal at her apartment. He arrived on time to find the other band members but no Nina. The men sat around for what seemed like hours, and when Nina finally came in she offered no explanations and barely acknowledged Bobby. “Let’s get this rehearsal going ‘cause I got to get to Pep’s in Philadelphia,” she told them, referring to the popular jazz club. After the group ran through some numbers, Nina reminded Bobby to make the Pep’s date, which was her way of saying he had the job.

THE JUNE 1960 METRONOME, a national magazine for jazz enthusiasts, devoted a full page to Nina. “Tense, taut, sensitive, religious, intelligent. Rare,” the piece began. “A singer of rich versatility.” After providing the usual background on her life, the article let Nina speak in her own words to answer radio host Ralph Berton of New York’s WNCN.

“Frankly, I don’t like what you do,” Berton had said in an on-air interview. “It’s stagecraft, commercial.”

Instead of taking offense, Nina delivered a variation on the theme of survival, words once again embroidering her story and once again evoking the “blue lights and sad memories” Frank Brookhouser had picked up in her earliest club dates. “I don’t know how this will go down with listeners,” she said. “Perhaps, if it’s understood, it won’t hurt. You are right to a certain extent. For years I worked only on my music. I very nearly starved to death,” she added. “It had a profound effect on me. I don’t want that to happen again. Sure there’s staging and commercialism now.”

The same sober themes had emerged a couple of months earlier, when Nina talked to a reporter from Rogue magazine and alluded to childhood deprivations much more stark than any her siblings recalled. “I’m scared, scared of many things, but mostly scared of poverty. All of my life I’ve felt the terrible pressure of having to survive,” she said. “Now I’ve got to get rich …very very rich so I can buy my freedom from fear and know I’ll always have enough to make it.”

The “staging and commercialism” would disappear, she told Metronome, when “I don’t have to worry about food, about money and rent, then people will hear the real Nina Simone. I can promise you that.” She gave no clue about who the “real” Nina Simone was, though evidence was mounting, even if she didn’t acknowledge it, that Nina was finding her niche in the world of jazz.

NINA HAD HIRED a new agent, Bertha Case, whose primary work was representing writers. She first heard Nina in New Hope in 1957 and wanted to represent her right then. But Nina said no. They reconnected in New York nearly two years later when the most unusual coincidence brought them together. A young writer had submitted a television play to Case and had included in the package special music and lyrics made in a home recording. As Case listened, she recognized Nina’s voice. She renewed her offer immediately, and this time didn’t take no for an answer. Case got to work right away on Nina’s behalf, and NBC paperwork suggests that it was she who booked Nina’s second appearance on the Today show, to air June 9. Nina actually taped the show the day before, and perhaps because this was a return visit, she seemed relaxed in the studio, chatting amiably with host Dave Garroway as she waited to perform her numbers. Before she went on the set, she sought out Fred Light, who was the only black associate director employed at NBC-TV.

Garroway introduced Nina as she might have described herself: “fairly new and very different …and she’s got a way with songs that combines the musicianship of Juilliard with the liveliness of a schoolyard … at recess time that is.” Nina sang her signature “I Love You, Porgy,” then switched to traditional blues, “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out.” It was a more daring choice than the show tunes of her previous appearance, and Garroway seemed to appreciate it. “Who wants to be reminded of the harsh fact that nobody wants you when you’re down and out? You will …when you hear Nina Simone sing it… .”

On June 30 Nina and the trio played the opening night at the fifth annual Newport Jazz Festival, an event that was for many—performers and audience alike—a highlight of the summer. Al had played all around the United States, and Europe, too, so he barely raised an eyebrow at the heady milieu. But Chris and Bobby were wide-eyed with excitement. Everywhere they looked was someone important—Cannonball Adderley, Dave Brubeck, Dizzy Gillespie, Maynard Ferguson.

“We had a case of the jitters,” Chris admitted. But Nina took charge.

“Just walk out there,” she told them. “And focus on me.” Chris and Bobby nodded and waited along with Nina and Al for MC Willis Conover to introduce her. She couldn’t have asked for anything more. Nina, Conover said, “is in the tradition of pianists who also sing and of singers who also play piano, such people of course as Nat King Cole, Jeri Southern, Carmen McRae, Erroll Garner.” But perhaps the best part was the way he pronounced Nina’s name. He hit each vowel with a continental flare, exactly as she had imagined it six years earlier at the Midtown: “Miss Nee-na See-mone.”

Nina opened with a piano solo, thick major chords that were more gospel than blues, to set up “Trouble in Mind.” Bobby came in with a simple repeating pattern, a steady thump of the bass drum and one beat of the cymbals in each bar. Nina played the intro another five times, but she was still finding her groove. “One more!” she shouted. On the seventh pass she signaled that she was ready: “Go boys!” she said as the song took off: “Trouble in mind, I’m blue.” By the end Nina’s arrangement had evoked a revival meeting as much as a smoky club, but it underscored the optimism suggested in the last line,” The sun’s gonna shine in my back door someday.”

Nina was in good spirits after finishing “You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To.” “Hi everybody,” she said. “We’re sorry we can’t see you, but we want to say hi anyway.” The crowd gave her an appreciative chuckle. “Can you hear me?”

“Yes,” the audience shouted.

“It feels kind of strange to be up here,” Nina went on. “I’ve heard about this place for five years. This is the first time we’ve ever been here, and we’re happy to be here. I want you to know that.” Nina had gotten up from the piano and sat down at a stool in front of one of the microphones. She asked for a tambourine.

“This is a folk tune—you must have heard it all your life. I did. It’s called ‘Little Liza Jane.’ We’ll get some rhythm started here and see what happens.” Al and Bobby responded with a brisk pace, but Nina wanted more. “Come on!” she exhorted.

They picked it up and got louder.

“That’s better!”

Now she turned to the audience. “I can’t hear you,” she hollered. “I think they’re shy.” But by the time she shouted “Let’s go now!” hitting the tambourine for emphasis, the crowd caught her mood, and together they turned the Newport festival into a foot-stomping hoe-down. Nina closed her set with a rollicking “In the Evening by the Moonlight” that would have been equally at home at St. Luke CME. She built to the final crescendo, punctuated with that familiar “ba-ba-BA,” and as the audience responded enthusiastically, she declared, “Yeah! All right!”

As happy as Nina looked onstage, John Hammond, a producer, writer, and all-around musical entrepreneur, remembered that later she was in a bad mood backstage. Nobody knew why. Jane Pickens, a former member of the singing Pickens sisters, found Nina’s set thrilling and wanted to congratulate her. Hammond took her to see Nina but was waved off by a man outside her dressing room. “Stay away,” he told them. “She’s in a rage.”

Pickens would have none of it. As Hammond recalled, she barged right in and gave Nina a big hug. “Honey,” Pickens said, “you’re the most wonderful singer in the world. This was the greatest experience of my life.”

Nina just melted, Hammond said. “She loved it.”

COLPIX HAD RELEASED two more singles from the 1959 sessions, though since “Porgy” Nina had yet to return to the charts. The label was also trying to broaden her reach, having made an arrangement with an Italian company to release an Extended Play 45 made up of four Colpix tunes. Musica Jazz, an Italian magazine, published a story about the record along with a photograph of Nina offering a new professional look, that of sophisticated chanteuse. She wore a braided hairpiece on the top of her head, which made her look a little like Luisa Stojowski, one of her Juilliard teachers, and she had on an off-the-shoulder black evening dress.

On the recommendation of his friend Max Cohen, who was still Nina’s lawyer, Art D’Lugoff booked her for most of July at the Village Gate, his club on the corner of Bleecker and Thompson not far from the Vanguard. Art had opened the Gate in 1958 and immediately earned a reputation as an adventurous programmer. One of his first shows packaged the American premiere of Edgard Varèse’s “Poème électronique,” which called for a darkened room and music made entirely by electronic equipment, with contemporary classical music performed by a quintet and an octet. With a seating capacity of 450, the Gate was one of the larger club venues, and when he took it over, the acoustics impressed him. Friends in the record business said that if he didn’t like running a club, he could turn the place into a recording studio. Art realized that he could do both, and because he had enough room to separate the equipment from the stage, live recordings would sound better at the Gate than at other nightspots.

Art took to Nina’s music immediately, though he could see that she “had an attitude.” But given his penchant for innovative shows, he appreciated more than most Nina’s improvisations, even when they didn’t work. In his mind that’s what made them “true improvisation.” He had a feeling that this first booking could be the start of a long relationship. If Nina failed to reciprocate immediately, she had to admit she was enjoying the job. The music, the venue, and the city combined to make her feel like “Queen of the Village.” She’d found the same audience that had kept her going at the Midtown—the kids, as she called them, “the hip New York jazz crowd, and the people who hung out in the Village coffee bars and clubs,” the beats like Don, “and they all hit on my music.” A writer from the Citizen Call, another of New York’s black newspapers, had taken in one of Nina’s shows midrun and later dubbed her music “chamber jazz.”

Her growing success brought more attention from the press, and during a mid-August week in Detroit, where she was booked at the Flame Show Bar and a local jazz festival, the Michigan Chronicle, the city’s black newspaper, sent a reporter to the Statler Hilton to talk to her. Like her comments to Metronome and Rogue, Nina’s reflections on this afternoon were another pained reverie on the past. Tryon became a place not only of poverty but of put-down, too, the lessons with Miss Mazzy and the encouragement of family exiled from memory. “The kids made me sing bass …or so low you couldn’t hear me,” she told the Chronicle’s Paul Adams. “Darling, I was poor, poor, poor, too.” A split second later she picked up the phone in her room to illustrate how much things had changed. “Waiter,” she instructed with prima donna flair, “bring me up a nice lobster and a champagne cocktail.”

Her jocular mood disappeared as soon as she hung up the phone. “Darling, I was poor, poor, poor and they made me sing bass,” she repeated. “After that there was high school—I felt trapped and scorned in a hostile world. But there was a piano,” she continued, and then Juilliard. “Then there was ‘I Love You, Porgy,’” the very mention of the song lifting her spirits. “And darling, today, they don’t make me sing bass anymore.” Nina threw back her head “and laughed and laughed,” Adams reported. She disclosed she was seeing a psychiatrist, only hinting at the reasons why in a seeming stream of consciousness. “Fear—Yes, I am afraid, so afraid. Maybe I’m afraid because I don’t want to sing bass anymore. Maybe I’m afraid of this cold, hostile world, of life, of love, of poverty …and of people. People can be very vicious. Believe me, I know. Can’t they, Faye?” Nina was looking at her friend Faye Anderson, who had come on this trip, too, and she nodded in agreement.

Such complicated emotions inevitably found their way into the music, and when Nina plumbed the depths, she turned a song from the routine into an intoxicating drama. Collins George of the Detroit Free Press, who had attended the jazz festival, marveled later at how she held the audience in thrall, building one number to what sounded like its climactic end only then to “let out her voice. It weaved in and out of the instruments in a low moaning wail that only served to intensify the fever heat of the performance. It was utterly breathtaking.”

By the time Nina and the trio returned to New York for their September engagements, her second single had reached the Billboard Top 100. “Nobody Knows You,” which she had performed on the Today show, registered at number ninety-three September 5. But it only stayed another week before dropping below the cutoff. Nina barely noticed. She was preparing for her most important booking the following week, Sunday evening, September 11, on TheEdSul-livan Show, which in typical fashion would include a comedian, a dancer, an “illusionist” from Europe, a juggler, and the self-described sex kitten Eartha Kitt.

Nina came on in the last segment. “The winner of all the polls this season for the most promising young recording star is a girl from North Carolina via Philadephia,” Sullivan said as he introduced her. “Let’s have a big hand for Nina Simone.” Nina was sitting at the piano when the camera showed her. She was wearing a long print cocktail dress with the same kind of drape as the white satin ball gown she had worn at Town Hall. Her elaborate makeup—eyeliner to accentuate her dark eyes and pencil applied to thicken her already heavy brows—only served to emphasize her facial expressions.

Sullivan had announced that Nina would play “Love Me or Leave Me.” Her arrangement began with a few heavy chords before she shifted into single notes struck briskly and with purpose. Then she launched into an up-tempo version of the song. After the first chorus, a guitar could be heard—probably Al—accompanying her on a variation of Bach’s Fugue in C. Their point-counterpoint went on for nearly a minute, and television viewers could see Nina’s hands racing over the keyboard. She resumed the vocals and ended the song with a triumphant flourish of chords.

By the time the applause subsided, Sullivan had come over to the piano. “Congratulations, young lady,” he said before introducing her other number, “I Love You, Porgy.” Halfway through the song, Nina took her hands off the keyboard and rested them in her lap. “Someday I know, I know, someday he’s coming,” she sang soft and slow, turning to the audience in that moment. Then without looking, she put her hands back on the keyboard in exactly the right place to play an unusual trio of chords as the bridge to the final two choruses. Nina got up from the piano and walked over to Sullivan.

“Wonderful,” he told her as they shook hands.

From the first night she sang at the Midtown in Atlantic City, Nina thought of her voice as “a third layer” of music to complement her right and left hands on the keyboard. Though she wanted to disguise her limited range, a dusky timbre made her voice a distinctive one, and this night’s performance confirmed that her plan was a good one. The audience, and Sullivan, too, let Nina know that she had drawn them into her world in the short time they were together.

RIGHT AFTER THE SULLIVAN SHOW Nina and the trio headed to Chicago for a week at the Lake Meadows Restaurant, known to aficionados as “Stelzer’s,” even though its original owner had long since departed. Current manager Dick Benjamin got all the mileage he could out of Nina’s Sullivan appearance, promoting her in Defender ads as “direct from Ed Sullivan’s Toast of the Town.” Though the restaurant had been created to serve the surrounding Lake Meadows development at Thirty-fifth Street and South Park on Chicago’s South Side, it also drew students from the nearby Illinois Institute of Technology, making it the kind of place for the same audiences Nina had found in Atlantic City and New York.

Brigitta Peterhans, a white foreign student who had come to love jazz, and her local classmates John Vinci, who was white, and David Sharpe, who was black, were typical of the IIT students who came over to Lake Meadows as often as they could. Catching one of Nina’s shows, they loved the music but were unprepared for the edgy personality on display. If anything, Nina had become even more insistent on proper decorum when she played. She might be firmly in the world of nightclubs, but she refused to drop the sensibility of a concert pianist. Unhappy that some of the men at the bar were talking loud enough to be heard over the music, Nina stopped. “I’m the one getting paid here,” she snapped. “If you guys sit over there talking, I might as well quit.”

Such confrontations notwithstanding, Nina was a good draw in her first week. So good that she was asked to stay on for a second. But Charles Walton, a music teacher who practically made Lake Meadows a second home, remembered Nina as “moody” and reluctant to sing for much of the second week. “She just had her evil moments,” Walton said, finding no other explanation. “She just played the piano. It killed her crowd.”

HAVING ALREADY BEEN FEATURED in Ebony, Nina was profiled in the October issue of Sepia, an Ebony look-alike. This story, too, which included a full page of photos, highlighted Nina’s melancholy side, starting with the headline “Little Girl Blue” and a subhead asserting that “the bluesy gal who whispered ‘I Love You, Porgy’ is still sighing sadly.” Perhaps because the article was prepared so far in advance Nina and Don were depicted as a couple. Several of the photos showed them together, some of them in the apartment on Central Park West. Nina did allude to their troubles when she explained that “Porgy” was so successful “because I am singing about myself, and I think my audience realizes this, too. This song is for real, and I am singing about my husband,” she said, noting how many times they had broken up. Don told Sepia the couple was planning to go to Europe, probably France, where he could paint and Nina could compose. “Let’s face it,” she interjected in a now-familiar refrain. “I’m doing what I do now for money, and I hope the money I make can help me achieve the things I really want,” though she did not specify.

A trip to France with Don was scarcely in the cards, so Nina stayed busy with present commitments. On October 21, Art D’Lugoff, who had been a concert promoter before he opened the Village Gate, sponsored Nina and the trio for a full evening at Hunter College. It was a solo bill, so she didn’t have to confine herself to a half-dozen tunes that would fit into a thirty-minute set. She could stretch out her piano interludes as long as she wanted. During the evening she introduced a song she called “one of our favorites—we’ve been doing it all of four days and we’re scared to death of it.” It was her first public performance of “Zungo,” an African chain gang song arranged by one of her new friends, Michael Babatunde Olatunji, a Nigerian conga drummer who was currently playing with the Herbie Mann Afro Jazztet. Though Nina had been incorporating African motifs into her music almost from the beginning, this was the first time she gave them such full expression.

The concert was also a chance to showcase the trio, together four months now and clicking. Nina remained enamored of Al’s guitar work, and she gave him a solo instrumental in the second half. Chris and Bobby were increasingly comfortable even when Nina went off on a tangent in the middle of a song. They were confident she wouldn’t call them out onstage even if they failed to follow her. “Her thing with me was always more intonation,” Chris explained. “If you’re going to play B flat, give me a B flat. Don’t give me something between B flat and B.” She also chided Chris for relying too much on the written charts. “When are you going to learn, when are you going to memorize that?” she would ask. “If you’re going to be my bass player, I want you to be off the book.”

The Times’s John Wilson was at this concert, too. He coined a new term, “Simoneized,” to describe the way Nina poked experimentally into “unexpected crannies” of a song. His main criticism of her work were the many “thunderous Brubeckian endings …There are, as she must know, some things that end not with a bang.”

IN THE MIDDLE OF NOVEMBER, Nina stepped forward purposefully—and at this moment uncharacteristically—as an agent of social change. She was a lead plaintiff in a lawsuit challenging New York City’s cabaret card regulations, which, since 1941, had required all cabaret employees, including performers, to get police identity cards. All applicants had to be fingerprinted and photographed in addition to paying a $2 fee. Anyone with a criminal record was ineligible for a card under rules issued by the State Liquor Authority. Most famously, Billie Holiday was unable to perform in New York City clubs—though she could play Carnegie Hall—because of a narcotics violation and subsequent prison sentence. And Frank Sinatra refused to play the city’s cabarets because he considered the card requirement to be “demeaning.” The lawsuit, also joined by orchestra conductors and music technicians, challenged the right of the police commissioner to require the identification cards. It was prompted by the case of humorist Richard Buckley, known as “Lord Buckley.” His card had been confiscated by the police, who claimed he had lied about his prior drug arrests. Buckley was struggling to regain his card so he could work in the city when he died of a sudden stroke.

Nina took another decisive step a week after the lawsuit was filed. She signed a carefully worded letter to Art D’Lugoff, quickly made public, explaining that “I do not recognize the authority of the Police Department with regard to my employment contracts unless there is something inherently criminal or illegal in these contracts. There are no such elements in my contracts with you or with anyone else. I, therefore, decline to make available to you any information as to whether or not I possess a Cabaret Employee’s Identification Card.” Max Cohen, still Nina’s lawyer, drafted the letter, having done most of the legal work on the lawsuit. His concluding rhetorical flourish was the verbal equivalent of one of Nina’s “thunderous Brubeckian endings”: “I have not abdicated my status as a citizen of the United States by becoming a performer and therefore refuse to have my Constitutional rights and privileges unlawfully assaulted by the Police Comissioner of the City of New York.”

Nina’s embrace of the cause—completely voluntary, Art said—actually brought her more publicity than her recent performances. Variety, which had ignored them, made much of her new stand. A story in the December 14 issue put Nina in the headline about the conflict: “Songstress Won’t Tell if She Has Card in New Test of N.Y. Police Authority.”

The “test” would turn into a six-year effort that finally resulted in the end of the cabaret card system in 1967, though Nina was not a part of the case on a continuing basis.

WHEN SHE WAS STILL Eunice Waymon, Nina couldn’t know that her brief encounter with Langston Hughes at the Allen School presaged one of her most cherished friendships. He made the first overture in his newspaper column, “Week by Week,” with a fan letter that was more imaginative tone poem than journalistic prose: “She is strange. So are the plays of Brendan Behan, Jean Genet, and Bertolt Brecht. She is far out, and at the same time common. So are raw eggs in Worcestershire and THE CONNECTION. She is different. So was Billie Holiday, St. Francis, and John Donne. So is Mort Sahl, so is Ernie Banks. She is a club member, a colored girl, an Afro-American, a homey from Down Home. She has hit the Big Town, and the big towns, the LP discs and the TV shows—and she is still from down home. She did it mostly all herself. Her name is Nina Simone.

“She has flair,” he went on, “but no air. She has class, but does not wear it on her shoulders. She is unique. You either like her or you don’t. If you don’t, you won’t. If you do—wheee-ouuueu! You do!”

Hughes’s column first ran November 12 in the Chicago Defender and was picked up later by other newspapers. It made for an intriguing confluence of events, to have one of black America’s most prominent literary figures champion Nina at the moment that she was beginning to see her art as something larger than herself, connected to the world around her in a way that remained to be fully defined.