Nina’s return to Carnegie Hall January 6 was as much coronation as concert. Undeterred by a snowstorm and blustery winds, her fans filled every available seat, lined the balconies, and even spilled out onto the stage where space permitted. They got restless during a half-hour delay that Nina gamely explained was caused by the theft of Rudy’s guitar. But they came to attention when she went ahead without Rudy and her brother Sam, who had joined the band, while they searched for a replacement. She barely skipped a beat when applause announced their arrival onstage in the middle of a song.

Nina started the evening in churchlike fashion with “Draw Me Near.” “This is a nice groove to get into,” she said, “but let’s do the important ones first.” Those who knew Nina understood that meant “Backlash Blues,” “Strange Fruit,” and now “Turning Point,” with Nina in the guise of a white child asking her mother if her friend, who “looks just like chocolate” and sits next to her in school, can come over to play. The mother says no. “We could have such fun!” the child pleads. “Why no?” Nina paused for effect and lowered her voice. “Oh…I see.”

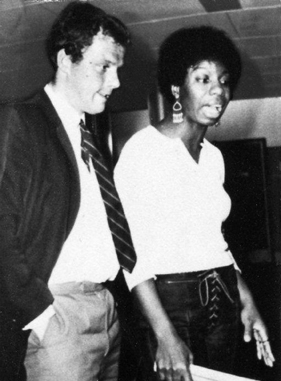

Nina and her brother Sam at Nina’s Mount Vernon house, spring 1968

(Courtesy of Sam Waymon)

It was her custom when she finished to look across the lights and ask in an offhand, almost lazy way, “Did you get it?” The emotional current running through Carnegie Hall left no doubt that the audience did. A few weeks earlier in San Francisco, Ralph J. Gleason, the Chronicle’s critic, had seen her perform the same magic, marveling that “she had people from Georgia and Alabama in the crowd and still put over her message songs.”

Andy’s company and Ron Delsener co-sponsored the Carnegie concert, evidence that Delsener’s initial instincts about Nina were right: they could get along, and she was a good draw. Variety reported that the sold-out performance brought gross receipts of $11,000. But Andy still worried that Nina’s provocative material could cost her. Gleason had actually addressed the subject of controversial black artists in one of his recent columns and cited Archie Shepp as one who believed an economic boycott existed against him and others who spoke up. One of Gleason’s friends said he found “a lot of hate” in Nina, and while the observation didn’t surprise him, Gleason wrote, he was saddened. “It struck me that this is the kind of reaction a great many people in this society have when someone makes them think or face an issue. The jazz musicians are and always have been wave makers by their implicit stance (their very existence brings you face to face with the problem of color) but they have played it rather than said it out loud.” Nina and the other artists “who are newly speaking out in the jazz world and the pop world,” he added, “are going to make it hard for any of us to avoid facing up to the reality behind the American dream.”

ON FEBRUARY 29 Nina opened a two-week stint in Vancouver, British Columbia, at Marco Polo, a supper club owned by one of the city’s prominent Chinese families, whose manager had a penchant for booking some acts that hadn’t yet made it, those on the downside (a literally staggering Bill Haley), and on special occasions genuine stars like Nina. The club’s full-time MC, Harvey Lo, combined fluency in Cantonese, Mandarin, and English with the skill of a world-class yo-yo champion. He opened every night by singing a song and doing a few yo-yo tricks before introducing the main act. Nina hated it. “Andrew,” she complained, “do I have to follow this every night? Is there any way we can get him off?”

But there wasn’t, so Nina usually arrived onstage in mild disgust, letting those with the best seats see “a look that could stop a truck with no brakes,” according to Henry Young, a popular local guitar player who was in the house band. “But when she took the facade off,” he added, “you could see all these beautiful features.” Henry felt a deep connection to Nina’s music because, as the son of a Ukrainian woman and a Chinese man, he, too, had faced discrimination. “You gotta remember,” he explained, “I’m not white. I suffered the same prejudice as Nina did. You really know what she hits,” he added. “It’s not about show business. It’s about emotional life.”

Henry wanted to meet Nina, and he thought Rudy was his best route to an introduction. One night he simply asked if he could sit in. Rudy took the request to Nina, and perhaps recalling the immediate connection with Al Schackman when he had appeared out of nowhere, Nina said yes. “But you don’t know the songs,” she reminded him. Henry told her not to worry. His ear was good enough to pick them up.

“She looked at me with these glaring eyes,” Henry recalled, seeing them still after forty years. “She scared the shit out of me.”

“Are you black?” she asked him.

“I’ll be whatever you want me to be,” Henry replied.

It didn’t take long for Nina to render her verdict. “You play like a brother,” she told him. “You have black blood in you.” Henry didn’t say anything, but he silently thanked Rudy, who whispered the right key if something got tricky and encouraged him to relax. Late one evening Nina and Andy went to hear Henry at the Elegant Parlour, an after-hours club owned by the future comedian Tommy Chong and a favorite of R&B musicians. By the time they left for the Troubadour in Los Angeles, neither Nina nor Andy knew how fortuitous their meeting had been.

“THE GREAT THING about Miss Simone is that she rarely makes a mistake on stage,” Variety said of Nina’s week at the L.A. club. “She gives the audience everything they want while clicking it off with superb pacing.” The reviewer also doled out praise to the sidemen, who now included Buck Clarke, the New York drummer who had played some dates with Nina a few years earlier. But more change was coming. When the L.A. job was over, Rudy announced he was leaving for The Fifth Dimension. The band’s offer was too good to pass up. Nina was going to miss him—she often introduced Rudy as “our rock of ages”—but she and Andy remembered how much they liked Henry. So Andy called him up and invited him to join the band in New York when they returned the first of April.

“I canceled all my jobs and left,” Henry said. “When somebody like that phones you, you don’t say no.” Andy sent him a plane ticket and a contract with terms that were the best he’d ever seen. Not only that, when he arrived in New York Andy was waiting for him at the airport and had arranged a room for him at a YMCA not far from the Fifth Avenue offices of Stroud Productions. He handed Henry a sheaf of arrangements and told him to be ready for a rehearsal. Nina was scheduled to play the Westbury Music Fair on Long Island on Sunday, April 7, and RCA planned to record the evening live for Nina’s next album.

Rudy’s wise counsel aside, Henry was a nervous wreck when he showed up for the rehearsal. But Nina put him at ease: “You know what, child, throw the music away, and let’s just play from the heart.”

Their first performance together scarcely went according to plan. On April 4, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was gunned down at his hotel in Memphis as he prepared to address striking san-itation workers. Though devastated, Nina professed no surprise at King’s killing. “It was the traditional white American tactic for getting rid of black leaders it couldn’t suppress in any other way,” she wrote in her memoir. “Stupid, too, because the thing that died along with Martin in Memphis was non-violence…It was a time for bitterness… .”

President Johnson had declared Sunday, April 7, to be a day of mourning, and Andy considered canceling the Westbury date right up until the last minute because Nina was so distraught. But he found a way to put her at ease, and she found comfort in talking to the band members one by one in the dressing room. She told Henry she was sorry his first job was under these circumstances. Finally onstage, Nina offered a subdued welcome to the audience. “We’re glad to see you, and happily surprised with so many of you. We didn’t really expect anybody tonight, and you know why. Everybody knows everything. Everything is everything …but we’re glad that you’ve come to see us and hope that we can provide…” and Nina paused to look for the right word but all she could come up with was “some kind of something for you, this evening, this particular evening, this Sunday, at this particular time in 1968. We hope that we can give you some—some of whatever it is that you need tonight.” She didn’t say so explicitly, but Nina needed something too, and drawing on every bit of her talent in the charged moment, she expressed her sorrow the best way she could, through her music.

For twenty minutes Nina wove a tribute to Dr. King through three songs, starting with “Sunday in Savannah,” one of the first songs she had recorded, about going to church. Tonight, she said, the audience should think of it as Sunday in Atlanta, where King’s funeral would take place. Then, she explained, Gene Taylor had written a song just the day before to honor the slain leader: “Why? (The King of Love Is Dead).” “Course, this whole program is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Martin Luther King. You know that,” Nina added.

“What’s gonna happen now to all of our cities?” she cried out. “Our people are risin’—they’re living at last even if they have to die.” She was chanting now more than singing, striking a chord here and there, Henry following her lead on the guitar. Then she swung into a gospel rhythm: “He had seen the mountaintop, and he knew he could not stop, always living with the threat of death ahead.” What would happen, she asked, when the king is dead?

Then Nina stopped. She wanted to talk, and while Sam played the organ softly behind her, she spoke of those who had already died: her dear friend Lorraine Hansberry, Otis Redding, John Coltrane. “We can go on—it really gets down to reality, doesn’t it? We are thankful, but we can’t afford any more losses,” she continued. “Well, all I have to say is that those of us who know how to protect those of us that we love, stand by them and stay close to them. And I say that if there’d been a couple a little closer to Dr. King he wouldn’t a got it, you know—really. Just a little closer then,” she added quietly, “stay there, stay there, we can’t afford any more losses.”

“Mississippi Goddam” was the final piece, updated to reflect current events: “Alabama’s got me so upset./Memphis made me lose my rest.” Midway she stopped again to talk, and this time Buck Clarke kept up the marching beat behind her. “If you’ve been moved at all, and you know my songs at all, for God sakes join me! Don’t sit back there! The time is now! You know the king is dead—the king of love is dead. I ain’t ‘bout to be non-violent,” she shouted.

The audience cheered.

“Whoa!” Nina exclaimed, perhaps startled by the ferocity of her own words and the crowd’s reaction. And then she picked up the song: “All I want is equality for my sister, my brother, my people, and me.”

Three weeks later, when she performed for the New York Urban League—and President Johnson attended the gala evening—the Amsterdam News reported that Nina’s passionate delivery of “Why?” had “wrung tears from the eyes and hearts of her audience.”

NINA HAD GIVEN SPECIAL ATTENTION to Buck at rehearsals, sensing his discomfort if she went on one of her improvisational jaunts. “When the show actually starts, Buck, when we’re up here, you keep your eyes on me,” she told him. “Whatever happens, just keep your eyes on me. Breathe with me…you’ll be all right.”

Buck took it to heart, but Nina remained unhappy with his appearance. Most of the time she didn’t mind that he dressed like of a dandy, but when he showed up for a job in Boston in a khaki safari jacket, top hat, riding boots, and carrying a switch, Nina had enough. He looked like a cartoon, or worse, a lawn jockey. “Tone it down,” she instructed. “Don’t embarrass me.”

Lester Hyman, a Boston lawyer, happened to stop by the club, Paul’s Mall, during Nina’s week there, though he didn’t know anything about her. “She just blew my mind, just extraordinary,” he said. Hyman was head of the state Democratic party and in the planning stages for a major fund-raising event. Although he had already booked society bandleader Peter Duchin and his orchestra, he thought Nina would be a terrific addition for the program.

He went back to the club another night to talk to Nina, but this time he found a completely different person. Two white men were talking constantly at one of the front tables, and Nina was perturbed. Finally she blew up. “You!” she shouted at them. “I get bad vibrations from you, and I don’t want you in here!”

The men must have been stunned, and perhaps choosing to avoid further confrontation, they left. Club owner Fred Taylor let it ride, figuring it was better to keep Nina in good spirits than tell her not to insult the customers. “You were always on pins and needles,” Taylor admitted, but he credited Andy with keeping “fairly good control of her.”

Hyman worried that the outburst didn’t bode well for him, and he asked Andy what to do. But Andy played it hands off: “You’re on your own buddy. You picked a bad night.” Hyman decided to forge ahead anyway. How much angrier could Nina get? He approached the dressing room cautiously, took a deep breath, and walked in hoping that a little humor would help.

“Miss Simone, I just”—and he stammered for a second or two. “I just would hate to be on the wrong side of you.”

Nina apparently thought this was hilarious. “She started to laugh,” Hyman recalled, and from then on they were fast friends. She readily agreed to do the fund-raiser.

NINA’S BUSY SPRING started with a concert at the Brooklyn Academy of Music sponsored by Soul East Productions, noteworthy, if nothing else, for the way it billed a Nina performance: “An Evening in Black Gold.” She returned to the Village Gate the next week with RCA hosting an opening night reception and springing for ads in several New York newspapers promoting her albums. After a trip to Chicago to play three shows at the Civic Opera House with Flip Wilson, Nina and the band headed to Europe the second week in June. It was Sam’s first overseas trip with her, and he couldn’t have been more excited, not only to see new places and meet new people but also to witness the tumultuous reception for his sister. In Amsterdam June 8, an overflow crowd of 2,500 applauded for a full minute when she walked onstage, and she hadn’t said or sung a word. Ben Bunders, a Dutch reviewer, noted later that the audience knew her from her previous trips and a few television appearances on the Continent. Promoter Paul Acket had added extra rows of chairs in the hall, but he could have sold hundreds more tickets if there had been space.

Though Nina made sure to sing some of her best-known songs, she used the occasion to introduce others that she and the band had worked up in the spring, notably “Why?”—to honor Dr. King—and another instant crowd favorite “Ain’t Got No—I Got Life” from the hit Broadway musical Hair. After listing the things she lacked, Nina sang with infectious energy about all that she did have: “I got my hair on my head, got my brains, got my ears, got my eyes. …”

Nina played the piano with such gusto during the evening that the other musicians, according to Bunders, had a hard time getting a note in edgewise. Only Henry found a moment to let loose with a long bluesy guitar solo, which earned him appreciative applause and a nod from another reviewer in the Amsterdam Daily News, who said Henry played with “a blues tonality of T-Bone Walker and the warmth of Kenny Burrell,” referring to two respected American guitar players.

Nina and Sam reveled in their time onstage. He had lived on and off with her, Andy, and Lisa in Mount Vernon, but performing together had an intensity all its own. “The truth is I reminded her of her daddy,” Sam said. “I look like my father. I could also see that she was lonely. She was very lonely for family.” Henry thought of Sam as a safety valve. “When she couldn’t see eye to eye with Andy,” he recalled, “she turned to Sam.”

Lisa had come on this trip, too, accompanied by a new nanny, a white woman named Cheryl whom Nina and Andy met at the Marco Polo. She was one of the hostesses but was eager to shake up her life and have an adventure. She hit it off with Andy and Nina perhaps because of her easygoing attitude. “She was such a charming honest person,” Sam said. Henry called her Nina’s “Sigmund Freud, 24/7.” “She would listen, listen, listen and never talk.” Sam joked that maybe Nina got along with Cheryl so well because she was Canadian and not an American. It was certainly high praise when months later Nina dropped Henry a note and told him that Cheryl “is working out very well—says she’s never coming back to Vancouver.”

Cheryl’s presence made it easier when Nina used a private concert in Morocco as an excuse for a four-day holiday. With Lisa taken care of, Nina relaxed at a seaside resort, even posing for photographs with some fans. The good time was diminished briefly by an episode at a hotel they were visiting, when some white people walked in and, in Nina’s view, acted in a way “that showed their prejudice. So we got up and walked out.” But that moment was forgotten by the time the group arrived in Switzerland, where they were among a handful of Americans in a largely European lineup at the Montreux Jazz Festival. Nina played the evening of the sixteenth to a crowd so large that some had to watch the performance from another room on closed-circuit television.

RCA had released Nina’s version of “To Love Somebody,” the torchy Bee Gees’ song, and now she sang it in her shows. The studio version had backup singers and an orchestra. Onstage Nina had only her piano, the guitar, bass, and drums, and Sam to harmonize. But this spare arrangement had an intimacy unrivaled by the record, Nina introducing the sweet melody of the chorus, “You don’t know what it means,” with soft chords that would not be out of place in church.

Though she and Sam meshed well musically, she chided him if he irritated her. When he played the tambourine too close to her during “Just in Time,” she looked at him and said, “Click click click,” prompting laughter from the audience. But Sam got the point and backed off.

Nina turned “See-Line Woman” into an audience participation number, giving the crowd a primer on how and when to shout “SeeLine” as she strutted about the stage. At the end of the eleven-song set, everyone cheered for more, and Nina obliged with her revival-styled “Gin House Blues,” the old Bessie Smith tune. “Don’t stop now!” she shouted, exhorting the audience to keep clapping. A few bars later, when she thought the drummer was slowing down, Nina hollered encouragement: “Come on, Buck!”

Michael Smith, reporting for the British paper Melody Maker, was among those who had to watch Nina via the television hookup. But it did nothing to diminish the power of her performance. Like Ralph Gleason a few months earlier, he acknowledged Nina’s focus on race and marveled how she could take “a predominantly white and initially indifferent audience and by sheer artistry, strength of character and magical judgment drive them into a mood of ecstatic acclamation. This was Black Power in its most dignified and enriching sense.”

The news that Senator Robert F. Kennedy had been assassinated in the midst of his presidential run dampened all the good feeling from the tour. Nina was still grieving over the death of Martin Luther King, and Kennedy’s murder upset her even more. She recalled the moment years later with such intensity that in her mind she had barely been able to perform at Montreux and Andy had to help her off the stage. But a recording of the concert and contemporaneous accounts indicate that she was in a good mood and in terrific form. “Thank you very much for having us,” she told the crowd. “We enjoyed it very much. And you’ve been a beautiful audience.”

NINA FREQUENTLY STARTED her concerts by letting the band play an instrumental before she came onstage. But with the deaths of Dr. King and Robert Kennedy so much on her mind and the memories of Lorraine and Langston always with her, Nina changed things up June 28 at the Hampton Institute in Virginia. The historically black school was celebrating its centennial, and when Nina saw the ten thousand people packed into the campus athletic field, she walked right out to the front of the stage. “It’s so wonderful looking out here and seeing all of you beautiful black people!” she exclaimed. The audience, which did include a sprinkling of whites, responded with a robust cheer.

Nina with Gerrit DeBruin at a television studio in Hilversum, the Netherlands, in 1968

(Courtesy of Gerrit DeBruin)

Though Nina rarely, if ever, opened with “Four Women,” on this night it felt like exactly the right thing. After she had worked her way through a few blues numbers, she ended on a somber note with another gripping presentation of “Why?” She and the band were rewarded with a standing ovation. The Christian Science Monitor’s Amy Lee noted afterward that Nina “let the whites present know unmistakably where things stand.” At Newport on July 4, in Philadelphia the next day with Ray Charles, and in New York in Central Park July 6, Nina elicited identical responses: rapturous applause from her fans and riveting attention when she slowed things down to remember Dr. King.

For the moment Nina said she yearned for tranquility. “I’m kind of tired of being controversial,” she told a reporter right after Newport, her song choices and some of her commentary to the contrary. “I want to settle down and be quiet. People come here expecting me to walk off the stage. But I enjoy Newport. It’s wonderful to play here before so many people. I love music,” she added, “it’s my life. It is the very foundation of my existence. I haven’t even begun to use half of my ideas.”

NINA AND THE BAND went to London in September to film an hour-long special, Sound of Soul, for British television. The studio audience, some two hundred individuals, most of them white and under thirty, sat arrayed in a circle around the bandstand. Nina made her entrance dressed in a variation of her fishnet outfit—white body stocking underneath the black see-through outer layer and dangling earrings at least five inches long that swayed to and fro as she walked around the stage. She bowed every few feet and extended her hand to audience members close enough to reach her, as though she was visiting royalty awaiting her subjects’ obeisance. “She was almost quite lovable,” Henry recalled, the most relaxed he had seen her.

The opening numbers elicited respectful if restrained applause, but soon heads bobbed to the music as the camera panned the room. By then it was time to change clothes. Signaling Nina’s return to the stage, Buck Clarke started rhythmic drumming on a set of bongos and kept it up as she entered in a bold print jumpsuit with billowing sleeves that whisked the floor when she bent over in an interpretive dance. She kept it up for a good five minutes, speaking only to tease an audience member who was trying to hand her the long microphone cord. “Get it, baby! Get it,” she chortled. All of this had turned into her elaborate introduction to “See-Line Woman.”

The final costume change came after a few more numbers. Now Nina reappeared in a sarong with a matching turban. The dangling earrings were replaced by pearl studs, all but ensuring that nothing distracted from the hat-and-dress ensemble. Striking a few chords familiar to anyone who had paid attention to the pop charts, Nina told the audience, “As you know, the Animals had a hit with this tune.” A hint of a smile was on her face. Then she presented a measured, compelling version of “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood,” suggesting, without actually saying it, that this was how the song should be performed.

Rather than explaining the origins of “Backlash Blues,” Nina improvised a verse in the song about what Langston had told her before he died: “When you finally made it, and the doors are open wide/Make sure you tell them exactly where it’s at/So they’ll have no other place to hide.”

“What I hope to do all the time is to be so completely myself,” Nina said, explaining such improvisations, “to be so much myself that my audiences and even people who meet me are confronted when they—oh wow! they’re confronted with what I am inside and out, as honest as I can be,” she continued. “And this way they have to see things about themselves, immediately. It’s like for instance, if I have a conversation with somebody, I can be honest every minute, and they’re forced to be honest. Whatever you get from my music,” she went on, “whatever you feel from my music is real, and it comes from me to you. Whatever it is, if it’s disturbing, eh, OK, but you’re part of that disturbance. If it’s love, whatever it is, and you get it from the music, then you got it from me …you can get your answers about me from my music.”

AFTER THE LONDON TRIP Henry returned to Vancouver to take care of family matters, and at roughly the same time, Gene Taylor and Buck Clarke went their separate ways. In a stroke of good timing, Al Schackman was back in New York and available. By happenstance, Nina and Andy found a new bass player, Gene Perla, whom they heard when they dropped in to a café in New York’s St. Marks Place. Impressed, Andy asked Gene afterward if he would come to a rehearsal October 21 at an Upper West Side studio. He made the date and was hired in time for a two-day trip to the Midwest: first a concert October 26 at Lake Forest College outside Chicago and then Detroit’s Ford Auditorium the next night.

After a subsequent four-day swing that took them from New York to Miami and Atlanta, Gene could see that Nina was unhappy with the drummer who had replaced Buck. Though he didn’t know Nina and Andy that well, he stepped forward anyway and told them to hire his talented friend, Don Alias. Nina said OK, and after the first rehearsal, she knew it was the right decision. She had also picked up a new organist who composed, too, Weldon Irvine. He had graduated from Hampton with a degree in English and music and had built a name for himself in New York music circles since arriving in 1965. The band was set for the foreseeable future.

Unbeknownst to the musicians, Andy and Nina had decided to change the group’s uniforms. They showed up at the next rehearsal with a couple of big bags, and instead of handing out new dinner jackets, they gave each of the men dashikis, one type of traditional African shirt. Gene’s eyes opened wide in disbelief when he saw the next thing: long gold chains with large medallions in the shape of Africa.

He held his tongue but only for a moment. “I’m not going to wear this,” he blurted out.

“Why not?” Nina asked, her irritation obvious.

“I’m Italian, not African.”

But Andy rushed in before the situation escalated. He calmed Nina down, and she and Gene reached an accommodation. He would wear the dashiki but not the medallion.

THE THIRD WEEK IN OCTOBER Nina had returned to the Billboard pop and R&B singles charts. RCA had released a record from a June recording session, “Do What You Gotta Do,” backed with “Peace of Mind,” and “Do What You Gotta Do” caught on, if modestly, staying on each chart for just over a month. The label had also released Nina’s third album, ‘Nuff Said, with most tracks coming from the live performance at the Westbury Music Fair in April, right after King’s assassination. “Why?” though, had been redone in the studio to eliminate Nina’s impromptu comments. It made for a shorter, more cohesive track but one that was nearly devoid of the emotion in the original. Perhaps RCA was uneasy about putting out something so raw that even Nina’s fans would blanch. Henry remembered the work in the studio as “cleaning up” some rough spots in the entire performance, and perhaps that’s all it was. It would take a generation before the full scope of Nina’s artistry and her pain that evening became available, when RCA released another record containing the entire tribute to Dr. King.

Shortly after ‘Nuff Said RCA put out another single, “Ain’t Got No—I Got Life,” the song from Hair, backed with “Real Real,” an upbeat tune that Nina had written. Though “Life” wasn’t doing much in the United States, it hit the charts in the United Kingdom, which prompted RCA to dispatch Nina to London for a round of publicity appearances, including coveted spots on two popular television shows, Top of the Pops and The David Frost Show. She agreed to do a meet-and-greet at Soul City, a small store in the middle of London, and took great pleasure in the sight of so many fans lined up to get in. “Well, it’s good to know they finally dig me,” she told one of them. True, she had to work and travel more, but “I’m having a ball, and at least this time I’m getting paid, and it’s about time, too.”

Nina reflected further on her career in an interview with Melody Maker, making sure to express her satisfaction with European audiences. “They seem to know all my records and when they were made,” she said. “I suppose the civil rights thing does come into it and has some bearing on their response, but in a lot of cases, I’m sure it has nothing to do with it.” Nina professed a disdain for politics and declared she was “not a politician. But when I’m on stage, of course, I’m conscious that I’m colored. I feel that I am upholding the prestige of my people and most of my songs are about the problem. I never forget that my first purpose is to bring art to the people,” she added. “Any social feeling I have must not overwhelm my music or be taken to extremes.”