Acalled Chris White, Nina’s former bass player, in the spring of 1989 and asked him to join Nina in Europe. Chris was surprised. Based on the last time he saw her, he didn’t think she was up to performing. They had been at a party in Newark at the home of Amiri Baraka, the poet and writer formerly known as LeRoi Jones. “I said to her twice, ‘Hello, Nina. How are you? This is Chris.’ And she looked at me and said, ‘Hello, dahling. How are you?’ She didn’t know who the fuck I was. I could have been the man in the fucking moon. She was totally out of it.” Later he learned from two young friends, Darryl and Douglas Jeffries, who had been recruited to look after her for a day, that she had been impossible. Promoters just getting started, they hoped that time spent with Nina might help their new business. They arrived at Baraka’s house, where Nina was staying, expecting to meet jazz royalty, but the woman they saw looked like a homeless street person. She was unkempt, dressed in an old black poncho and high-topped sneakers, carrying a peanut butter and jelly sandwich in one hand and a fifth of vodka in the other.

A musician friend had asked the brothers to come by with their portable video machine so Nina could play a European tape she had. But the tape and their equipment didn’t mesh, and she couldn’t watch it. The Jeffrieses tried to make up for it by taking her to a well-established soul food restaurant in the area. Things went pleasantly enough until Nina announced that she had to get to Waterford, Connecticut, for a meeting, and she ordered them to drive her. The brothers told her they had to stop at home first to get a few things. Nina apparently thought they were taking too long at the house, so she got out of the car and banged on the front door. Their mother, a registered nurse, answered to find an angry woman bellowing, “Do you know who I am?”

“Do you know who I am?” Mrs. Jeffries yelled back, and the shouting escalated until Darryl and Douglas got Nina back in the car. They arrived in Connecticut just before midnight. “She was ranting and raving” almost the whole way, Douglas said. “She was spewing at us. We hadn’t done anything. We had just met the lady.” But right after she found her friends and sat down at a piano, “all of that turbulence went away,” Douglas went on, the memory of this miraculous transition still vivid. “She was now in a safe harbor, and she came to herself. She was a living walking hurricane until she got to sit down at the keyboard, and then the serenity came over her.”

“She wanted me to stay the evening and comfort her,” Darryl added, which he declined to do. He and Douglas drove back to New York in a daze. “We thought we had found a mentor,” Darryl said, “and we ran into a tsunami.”

Al assured Chris that these kinds of episodes were few and far between. Nina was on medication for what had now been diagnosed as schizophrenia, and it kept her on an even keel more often than not. Several dates were booked, and besides that, Al told Chris that Nina had asked for him because she believed he understood her.

Nina had also relocated once again, this time to Nijmegen, the Netherlands, an inland city southeast of Amsterdam where Gerrit lived. He had put the move in motion when he realized that Nina needed a stable base. Over the last year he seemed able to handle her intermittent rages better than most, and he wanted her nearby. He never argued with her even when he was tempted to yell back. Instead, he listened patiently and then suggested possible solutions to whatever problem had set her off. On occasion, when he sensed that it would work, he first ignored her rantings and then looked right at her before sticking out his tongue. She dissolved into laughter, and the moment passed. Perhaps most important, though, Nina knew that Gerrit would not judge her. She must have sensed that it saddened him to see so much talent accompanied by so much pain. “I thought, ‘Poor Nina. You’re having an attack. How horrible for you.’ … Can you imagine if you can’t behave yourself. You wake up the next morning and ask ‘What have I done?’” Nina’s pointed humor, he added, revealed that she understood her own problems. The once-popular song “What Have They Done to My Song, Ma?” included the line “Look what they’ve done to my brain, Ma,” and Nina would sing it with gusto.

In Nijmegen Nina bought a small apartment and had the help of the self-styled “A-team” to assist her: Gerrit and Al along with Raymond, who was still booking her concerts. Roland Grivelle, Nina’s friend from Paris and the occasional road manager, also stepped in to help, and Leopoldo arrived just as Nina was setting up the place. “We took her out shopping and bought her furniture and dishes,” he said, and also a shopping cart, which Nina insisted she didn’t need. “You may not need it,” Leo explained. “That’s for whoever does the shopping for you.” Nina chuckled at the truth of the matter.

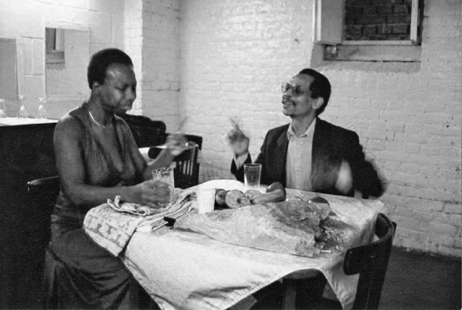

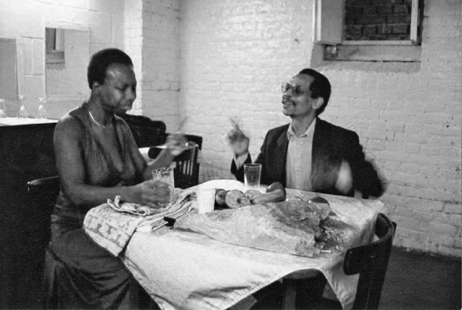

Nina with percussionist Leopoldo Fleming in her apartment in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, May 1989 (Gerrit DeBruin)

Gerrit knew that Nina appreciated all he had done even if she rarely showed it. He had rescued her from an embarrassing incident at the Grand Hotel in Paris a year or so earlier when, for no apparent reason, she was about to strike a complete stranger who was in the lobby. “I dragged her outside into the street and managed to push her into a taxi,” he explained. They drove around until she calmed down, and nothing more was said. A couple of months later back in Nijmegen, “she turned to me and said, ‘Gerrit, thank you for getting me out of that situation in the Grand Hotel.’” He was hardly prepared for the more extravagant gesture that came a few months later. He picked up the phone at his office one day to hear Nina demanding that he stop what he was doing and come to the apartment—immediately. She refused to take no for an answer, so Gerrit closed up the day’s affairs in his wine import business and headed over. When he walked in, Nina was standing by her piano in full concert makeup, pointing him to a chair nearby. “I’m so grateful,” she said. “I’m doing a private concert for you.” “She played for four hours,” Gerrit recalled, “and then she asked if I wanted an encore.”

NINA’S APARTMENT WAS CONVENIENTLY located next to the Hotel Belvoir, where Leo and the other musicians stayed. “It was very pleasant, a nice experience,” Leo remembered. Chris agreed. A photo from one of their first dates after his return, a concert in Oviedo, Spain, shows the camaraderie among the musicians and Nina. Everyone, to be sure, was older now. A much plumper Nina was wearing a tailored suit with a floral pattern that would be as suitable for dinner at an upscale restaurant as for the stage of a jazz club. Al’s hair was salt-and-pepper, and Chris, dapper in a double-breasted suit, still looked young, though not quite as boyish as the twenty-something who had played with Nina years earlier.

A handwritten set list, c. 1989 (Courtesy of Gerrit DeBruin)

The distance had given him perspective. The first time, Chris said, “part of what was interesting with the band was the fact that Nina was inventing herself. And when I came to her the second time, she was a known entity both to herself and to the public, and her intent was to attempt to be whoever she felt that was.” In the beginning, he went on, “I felt I was helping to create along with her. The second time I was there to provide just whatever it was she needed. So it was a different approach. The second time required a much more mature player.”

Chris had a birthday July 6, and he was touched that Nina threw him a party in Barcelona, not far from one of their festival dates. “It was just magnificent,” he recalled, the icing on the cake coming from a solo during an instrumental later on at their sold-out concert at the Lycabettus Theater in Athens. A reviewer singled him out for his “expressive bass.”

Nina’s model behavior onstage, however, was nowhere to be seen offstage when the antidepressants weren’t working. Just before Athens, when they were in Freiburg, Germany, Nina became so angry at Raymond—and no one knew why—that he and Gerrit decided that Raymond had to get out of the hotel for his own safety. She was still mad at Raymond when they got to Athens. In one wild moment, she grabbed a knife from a food trolley that was in her hotel room and went out in the hallway naked, determined to find Raymond. Gerrit had been unable to stop her, but he cried out, “Nina, you are naked. You better get dressed first.” Nina realized Gerrit was right and came back for her bathrobe. Then she stormed out again, and he went after her to ask that she listen to him if only for a moment. Hoping he could dissuade her from even more embarrassment, Gerrit told her that the Athens police would not take kindly to her stabbing someone and that if she was going to hurt Raymond, better to do it in London, where she would have more protections under English law.

“Well, Nina’s enthusiasm to kill Raymond cooled off,” Gerrit recalled, “and that evening we—Nina, Raymond, and I—had a wonderful dinner together.” Later, back in Nijmegen, Nina was perturbed that Gerrit had let her go out of her hotel room naked. He simply told her that as long she had a knife in her hand, he’d rather let her run around with no clothes on than get cut.

“Yes,” Nina said. “I understand.”

NINA’S CONCERN over her royalties had not abated. In the fall a San Francisco lawyer she had hired, Steven Ames Brown, whose specialty was royalty recovery, sued a California distributor, Street Level Trading, and the British-based Charly Records for breach of contract in a licensing deal made in 1987 for Nina’s Bethlehem recordings. The lawsuit charged that the two defendants were in breach of the deal and had committed fraud in the way they executed the arrangement. Nina claimed she was owed $200,000. She had been so outspoken in criticizing Charly for failing to pay her proper royalties that the label filed a defamation suit against her in a London court and added Brown to the litigation, too, after he spoke out on her behalf. All the legal maneuvering tied up any royalty payments until Nina’s suit was settled for an undisclosed sum in the summer of 1990. As part of the settlement Charly dropped the defamation claims.

(Brown also filed a separate lawsuit for Nina against Ron Berenstein, who ran Vine Street Records, alleging that he owed her $50,000 for the records that were made from her appearances at the Vine Street club. This lawsuit was settled, too.)

CLAUDE NOBS INVITED NINA back to Montreux for the 1990 festival, and at her performance July 13 she couldn’t resist mocking her reputation. Introducing “Four Women” and “Mississippi Goddam,” Nina announced, “These next two tunes are dedicated to the blacks of America, the blacks of Switzerland, the blacks of the Middle East, the blacks of Africa—and we’re all very happy that Nelson Mandela is free, right?” She was referring to the release in February of the black South African leader who had been imprisoned twenty-seven years. “They thought that I wasn’t political anymore and what a mistake to think that.” Nina smiled ever so slightly.

Leo, who was playing a host of percussion instruments on this date, remembered that a woman from Ghana was helping her now. In contrast to her two previous Montreux appearances, Nina was in full high-priestess makeup, heavy liner setting off her eyes, just the right shade of lipstick and rouge to pick up the reddish stripes in the dress she was wearing, which was made out of kente cloth. Her hair was in cornrows, and to finish off the look she had returned to those long dangling earrings she used to like so much.

Successful as this date was, it couldn’t match the delight of a four-city swing through Italy in the fall with her good friend Miriam Makeba, and Odetta, the folksinger from the United States Nina had known since her first days in New York. The tour was the brainchild of Roberto Meglioli, an Italian promoter who had been working with Miriam Makeba. He knew Raymond and knew Nina’s music and approached them about doing a joint project. “We would love to have a third point of view,” he explained, “and that’s where Odetta comes in.” Fortunately she was in Europe at the time and agreed right away to join the two other women. They called their tour “Three Women for Freedom.”

Roberto knew Nina could be temperamental, and he asked Raymond for advice. “I am very white. I am very Italian, not even American, I know what I am. She is famous. Is there anything I might say or do that could make someone uncomfortable?” Raymond had nothing specific to tell him, so Roberto relied on his own instincts. He would make sure she and the other women had first-class accommodations, and he would be very respectful, especially at their first stop, which was in Catania, Sicily. He had picked a lovely hotel that was near the water, and right away that endeared him to Nina. She was already swimming when a photographer from Corriere della Sera, one of the major Italian newspapers, arrived to take pictures. Roberto asked her if she minded being photographed and asked if she would like time to change.

Why on earth should she, Nina wanted to know. She liked the way she looked in a bathing suit, even at fifty-seven. She put on a big pair of sunglasses and posed “like a real diva,” Roberto said. “That was funny. Everything went smoothly.”

The evening of the concert seven thousand Sicilians packed the spectacular grounds in front of a centuries-old castle Roger the Norman had built to protect against Saracen invaders. With a combination of joy and relief, Roberto watched Nina’s set from behind the stage, grabbing Miriam for a giddy minuet while Odetta took a spin with the local police chief, who happened to be standing nearby.

Most of the time, Odetta said, Nina was “in a good place. She trusted both of us.” She was convinced, too, that Nina found some special peace in the water. “Everywhere we went on the Mediterranean, the vacation belt, we got there, we would hear a splash. It’s Nina in the water. She swam and just played. It was a joy to see she got so much pleasure in the water.” At other moments, when Nina was at the keyboard, Odetta sensed the darker moods. As a listener, she said, “all of a sudden you were within a storm on that piano.”

Roberto further endeared himself to the women with the accommodations he booked in Cagliari on the island of Sardinia. Each of the singers had her own villa that was equipped with a kitchen, and Roberto remembered that they cooked meals for one another just like great friends would do. He couldn’t be sure, but he thought because he had taken such care with the details of the tour Nina never said no to anything he asked of her, and he saw only her calm side.

Odetta had hoped the trio could tour the United States—Miriam was “modern Africa, I was what we bring from Africa to the United States, and Nina represented jazz, where it went, but there was no financing.”

AFTER SEVERAL FALSE STARTS and a bevy of possible co-writers, Nina’s autobiography finally appeared in England at the end of 1991. It wasn’t called “Princess Noire” after all but I Put a Spell on You. Her co-writer was Stephen Cleary, a British man who had co-produced and directed the filming at Ronnie Scott’s in 1984.

The book was less a reliable guide to Nina’s life and career than a window into her feelings about all that had transpired. To her faithful fans it mattered little that she mixed up the history of Tryon and surrounding Polk County, described events in her career out of sequence, some with considerable embroidery, and made a few individuals with whom she crossed paths more villain than the record warranted. She barely gave Sam a mention, and though she gave a nod to Al, she took no note of Chris, Bobby Hamilton, Lisle Atkinson, or Rudy Stevenson—her sidemen in those critical early years when she established her career. Regardless of its literary merit, the book brought a new wave of attention that overshadowed some less than stellar performances earlier in the year.

I Put a Spell on You was released in the United States early in 1992, and Lester Hyman was delighted that Nina was coming to Washington June 18 for a concert at George Washington University. He got tickets for himself and friends who were visiting from California. One of them was a big fan, and Lester promised he would take his friend to meet her. After the concert at Lisner Auditorium, he went to the stage door, told the security people who he was, and handed one of them a business card for Nina. “Miss Simone says she will see Mr. Hyman and no one else” came the reply.

“So I went back,” Lester recalled, “and I said, ‘Won’t you just say hello to my friends?’”

“No!” Nina exclaimed. “I just want to see you.”

Disappointed, Lester could only deliver the rebuff to his crestfallen friend and explain truthfully, “That’s Nina.”

George Wein sponsored Nina at Carnegie Hall the following week as part of the JVC Jazz Festival. The theme was a variation on her past returns to the city. Instead of “Nina’s Back!” it was now “Welcome Back, Nina,” along with Al, Paul Robinson, and Leopoldo. A hall filled with fans gave her all the appreciation she could want, even if she was once again in middling musical form. She found the energy, though, to give “Mississippi Goddam” enough bite to inspire the raised fists of the black power salute among the many blacks in the audience.

I PUT A SPELL ON YOU had prompted a French film crew to make a documentary about Nina, La Légende, with her full cooperation. Gerrit by her side, she went back to Tryon for a tearful reunion with Edney Whiteside, her first love. She wondered aloud whether her career had been worth it, wiping her eyes as he tried to console her. Holding her hand, he gently reminded her that this was what she had always wanted. Nina revisited the disappointment over her rejection from Curtis, declaring that she was still not over what in her mind was a case of obvious racial bias.

She spoke with passion about her most controversial songs of the 1960s. “I felt more alive then than I feel now because I was needed, and I could sing something to help my people, and that became the mainstay of my life. That became most important to me,” she said. “It was not classical piano, not classical music, not even popular music, but civil rights music. All my friends had either left the movement or were exiled or were killed,” she went on, “and so I was lost, and I was bitter, very bitter, paranoid. I imagined someone was out to get me, out to kill me every minute of my life….” As if to buttress this point, Vladimir Sokoloff, the Curtis professor who had taught Nina privately, was interviewed on camera, and he lent credence to at least some of her fears. He said that the CIA had come to ask him if there was any evidence that while she was his student “she was mixed up in all this rebellious uprising.”

“When the civil rights movement died,” Nina said, “and when there was no reason to stay and there was so much racial prejudice, I couldn’t bear it, and I didn’t think it was my home. I had to get out of there.”

The documentary didn’t shy away from Nina’s angry side. Excerpts from a tape of her swearing at a promoter were included over a still photo of her face contorted in rage. She demanded that he get her contracts to her hotel or she would destroy his event. “I know you’re a rich son of a bitch,” she yelled into the phone.

“Yes,” Nina said, smiling at the camera. “I guess I am a little capricious. I’m not easily aroused.” Then she took it back. “No, that’s not true. I am very emotional. I’m very disciplined, but I’m very emotional. When I don’t like something, I say it immediately. So I think people would say I’ve got a hot temper. I think so.”

Nina spoke of the estrangement with her father. “I wish he was here now,” she said, breaking into tears. She dismissed Andy, her former husband, in cutting terms: “I never enjoyed him in bed. He told people I was his sleeping pill.”

Perhaps the most significant element of the fifty-minute program was the apparent reconciliation between Nina and her daughter. Only a few years earlier she had spoken of her with disdain, after Lisa had her first child. “I don’t see either one of them,” Nina had said. “So as far as I’m concerned I don’t have a daughter Lisa. That’s good enough for me.” Now, in the opening frames of the documentary, she cried as she told Edney she had never seen her grandchild, who was now seven. “I wasn’t able to raise Lisa very well. I’m sure that we’ll make it up as months go by. We will make up for what we didn’t share during those years. She seems to think we can, and I think we can.”

Then Lisa, now an aspiring singer, had her say. “She wasn’t with me or around me. She was always with me musically. So I want to sing her songs. I would love to be able to do that and have her in the wings or in the audience or on the stage knowing that she’s appreciated, that she’s loved, and knowing that it has not been for naught.”

The documentary ended with a segment called “The Dream.” Nina wore an orange caftan and played a grand piano in an outdoor setting framed by neoclassical columns. Guests dressed in formal attire watched attentively from a garden. She spoke over strains of Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Fantasy. “It haunts me,” Nina said. “Especially when I’m alone at night. I do still wish I had been a classical pianist, but I don’t look back now. I am what I am. Who am I? I am a reincarnation of an Egyptian queen.”